Hakeem Noor-ud-Din

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2016) |

Hakeem Noor-ud-Din | |

|---|---|

حکیم نور الدین | |

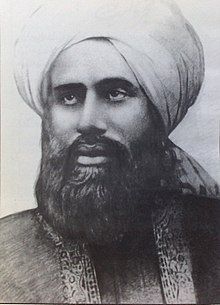

Hakeem Noor-ud-Din circa 1878 | |

| In office 27 May 1908 – 13 March 1914 | |

| Succeeded by | Mirza Basheer-ud-Din Mahmood Ahmad |

| Title | Caliph of the Messiah Amir al-Mu'minin |

| Personal life | |

| Born | 8 January 1834 |

| Died | 13 March 1914 (aged 73) |

| Resting place | Bahishti Maqbara, Qadian, India |

| Spouse |

|

| Children | Seven |

| Parents |

|

| Signature |  |

| Religious life | |

| Religion | Islam |

| Part of a series on

Ahmadiyya |

|---|

|

Hakeem Noor-ud-Din (also spelled Hakim Nur-ud-Din; حکیم نور الدین; 8 January 1834 – 13 March 1914)[2] was a close companion of Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, the founder of the Ahmadiyya Movement, and his first successor and first Ahmadiyya caliph since 27 May 1908.

Royal Physician to the Maharaja of Jammu and Kashmir for many years, his extensive travels included a long stay in the cities of Mecca and Medina in pursuit of religious learning. Noor-ud-Din was the first person to give bay'ah (pledge of allegiance) to Ghulam Ahmad in 1889 and remained his closest associate and confidant, leaving his home in Bhera and setting up permanent residence at Qadian in 1892.[3] He assisted Ghulam Ahmad throughout the course of his religious vocation, himself authored several volumes of rebuttals in response to criticisms raised by Christian and Hindu polemicists against Islam and was instrumental in arranging some of the public debates between Ghulam Ahmad and his adversaries.[4] After Ghulam Ahmad's death, he was unanimously chosen as his successor. Under Noor-ud-Din's leadership, the Ahmadiyya movement began to organise missionary activity with small groups of Ahmadis emerging in southern India, Bengal and Afghanistan, the first Islamic mission in England was established in 1913,[5] and work began on the English translation of the Quran.[6] His lectures on Quranic exegesis and Hadith were one of the main attractions for visitors to Qadian after Ghulam Ahmad. Many prominent scholars and leaders were his students, including Muhammad Ali and Sher Ali, who were themselves Quranic commentators and Mirza Bashir-ud-Din Mahmud who succeeded him as the caliph.

Family

[edit]Hakeem Noor-ud-Din was the youngest of seven brothers and two sisters and the 34th direct lineal male descent of Umar Ibn al-Khattab, the second caliph of Islam.[7][non-primary source needed] The forebears of Maulana Noor-ud-Deen, on migration from Medina settled down in Balkh and became rulers of Kabul and Ghazni. During the attack of Genghis Khan, his ancestors migrated from Kabul and first settled near Multan and then finally at Bhera. Among his forefathers were a number of individuals who taught Islam and claimed a proud privilege of heading a chain of descendants who had memorized the Qur'an; His earlier eleven generations shared this distinction. Among the ancestors of Maulana Noor-ud-Deen, there were saints and scholars of high repute. Sultans, Sufiis, Qazis and martyrs were all among his ancestors who once enjoyed an important place in the Muslim World. In Bhera (his birthplace), his family was accorded a high degree of respect from the beginning.[8]

Early years and education

[edit]Noor-ud-Din considered his mother, Noor Bakht, to be his first teacher. He used to say that he was fed the love of the Quran through his mother's milk. He went to a local school for his early education. His father Hafiz Ghulam Rasul, a devoted Muslim and parent placed great emphasis on his children's education. Noor-ud-Din spoke Punjabi as his mother tongue, but after hearing a soldier speaking Urdu, he fell in love with the language and learnt it by reading Urdu literature. His eldest brother, Sultan Ahmad, was a learned person who owned a printing press in Lahore. Once when Noor-ud-Din was 12 years old, he accompanied his brother to Lahore, where he fell ill and was successfully treated by Hakeem Ghulam Dastgir of Said Mitha. Impressed by his manner and his renown, Noor-ud-Din became eager to study medicine; but his brother persuaded him to study Persian and arranged for him to be taught by a famous Persian teacher, Munshi Muhammad Qasim Kashmiri.

Noor-ud-Din learnt Persian at Lahore, where he stayed for two years. His brother then taught him basic Arabic. In 1857, a traveling bookseller came to Bhera from Calcutta. He urged Noor-ud-Din to learn the translation of the Quran and presented him with a printed copy of five of the principal chapters of the Book together with their Urdu translation. Shortly after, a merchant from Bombay urged him to read two Urdu books, Taqviatul Iman and Mashariqul Anwar, which were commentaries (Tafsir) on the Quran. A few years later, he returned to Lahore and started studying medicine with the renowned Hakeem Allah Deen of Gumti Bazaar. This turned out to be a short stay and the study was postponed.[9][page needed] Noor-ud-Din was then sent to study at a School in Rawalpindi where he graduated with a Diploma at the age of 21 and thereafter, due to his academic abilities, was appointed the headmaster to a school in Pind Dadan Khan at the young age of 21. Noor-ud-Din first came into contact with Christian missionaries while he was in Rawalpindi.[10]

Further learning and travels

[edit]

Noor-ud-Din travelled extensively throughout India for next 4–5 years and went to Rampur, Muradabad, Lucknow and Bhopal to learn Arabic with the renowned teachers of that time. He learnt Mishkat al-Masabih from Syed Hasan Shah, Fiqh (Jurisprudence) from Azizullah Afghani, Islamic Philosophy from Maulvi Irshad Hussain Mujaddadi, Arabic Poetry from Saadullah Uryall, and Logic from Maulvi Abdul Ali and Mullah Hassan.

In Lucknow, Noor-ud-Din went in the hope of learning Eastern medicine from the renowned Hakeem Ali Hussain Lucknowi. The Hakeem had taken a vow of not teaching anyone. It is narrated by biographers that he went to his house for an interview and the discussion between them impressed the Hakeem so much that he eventually agreed to take Noor-ud-Din as his disciple.

The next city he visited was Bhopal, where he practiced medicine and was introduced to the Nawab of Bhopal during this time.

Mecca and Medina

[edit]In 1865, at the age of thirty-one, he traveled to the cities of Mecca and Medina. He stayed there for many years to acquire religious knowledge. He learnt Hadith from famous Sheikh Hasan Khizraji and Maulvi Rahmatullah Kiraynalwi. He gave 'bay'ah' (pledge of allegiance) to Shah Abdul Ghani, the Grandson of Shah Waliullah Muhaddith Dehlawi.

Return to Bhera

[edit]On his way back to his hometown, Noor-ud-Din stayed in Delhi for a few days. Here, he had the opportunity to attend a session of lessons by the leader and founder of the Deoband Seminary, Qasim Nanotawi and had a very good impression of him.[11]

In 1871 he returned to Bhera, his home town, and started a religious school where he taught the Quran and the Hadith. He also started practice in the Eastern medicine. In a short time he became well known for his healing skills and his fame came to the notice of the Maharaja of Kashmir, who appointed him in his court physician in 1876.

Royal Physician

[edit]In 1876 he was employed as the royal physician to Maharaja Ranbir Singh the ruler of Jammu and Kashmir. There are detailed accounts of his tenure as the court physician. All the schools hospitals of the state were placed under him. Initially he worked under the Chief Physician Agha (Hakim) Muhammad Baqir[12] but after Hakim Baqir's death he was made the chief physician himself. During his time as physician he is said to have given a lot of time to the service of Islam; and would often engage in religious and intellectual discussion with the Maharaja himself. During these discussions he was known for his fearlessness and frankness. The Maharaja and his son Raja Amar singh are said to have learnt the Quran from Noor-ud-Din.

The Maharajah is said to have stated once to his courtiers, "each one of you is here on some purpose or to seek some favour from me and keep flattering me, but this man (Hakeem Sahib) is the only person who has no axe to grind and is here because he is needed by the state. This is the reason why whatever is stated by Hakeem Sahib is listened to carefully as he has no ulterior motive."[13]

Being a scholar of Hebrew also, Noor-ud-Din was selected by Syed Ahmad Khan as the co-ordinator of the team of scholars in writing a commentary of the Torah from the Muslim viewpoint. During this time he was also actively involved with the Anjuman-i-Himayat-i-Islam.

Noor-ud-Din had been the royal physician from 1876. when Maharajah Partab Singh took over, Noor-ud-Din was made to leave the service of the state of Jammu in 1892 due to various political reasons. He was later offered the position in 1895 but declined the offer.

Introduction to Mirza Ghulam Ahmad

[edit]Noor-ud-Deen was constantly involved in religious debates with Christians and Hindus during his stay at Jammu. Once he was confronted by an atheist who asked him that if the concept of God was true, then how in this day and age of reason and knowledge, no one claims to be the recipient of Divine revelations. This was a question to which the Noor-ud-Din did not find an answer immediately.[13] During the same period, he came across a torn page from a book named Barahin-e-Ahmadiyya. The book was written by one Mirza Ghulam Ahmad of Qadian, who would later claim to be the Promised Messiah and Mahdi. Noor-ud-Din was surprised to see that the writer of the page was a claimant of receiving Wahi (revelation). He purchased the book and read it with great interest. He was so impressed by the book that he decided to meet the writer. Noor-ud- Din later recalled his first meeting with Ghulam Ahmad in his own words.[14]

As I arrived in a nearby place of Qadian, I got excited and was also trembling with anxiety and prayed feverishly....

Noor-ud-Deen later stated:

It was after Asr prayer, I approached Masjid Mubarak. As soon as I saw his face I was overjoyed, and felt happy and grateful to have found the perfect man that I was seeking all my life... At the end of the first meeting, I offered my hand for Bay'ah. Hazrat Mirza Sahib (Ghulam Ahmad) said, he was not yet Divinely commissioned to accept Bay'ah; then I made Mirza Sahib promise me that I would be the person whose Bay'ah would be accepted first...(Al-Hakam, April 22, 1908)

During his stay in Qadian, Noor-ud-Din became a close friend of Ghulam Ahmad and it is apparent in the writings of both persons that they held each other in highest esteem. Although this relationship soon became that of a Master and disciple and Noor Deen devoted himself as a student to Ahmad. He eventually migrated to Qadian and made his home there soon after he was made to leave his job in Kashmir. He would often accompany Ghulam Ahmad on his travels.

Noor Deen once asked Mirza Ghulam Ahmad to assign him a task by the way of Mujahida (Jihad). Ahmad asked him to write a book answering the Christian allegations against Islam. As a result, Noor-ud-Din wrote two volumes of Faslul Khitab, Muqaddimah Ahlul Kitaab[15]

After completing this, he again asked Ghulam Ahmad the same question. This time, Ahmad assigned him to write a rebuttal to Arya Samaj. Noor-ud-Din wrote Tasdeeq Barahin-e-Ahmadiyya.[16]

Leadership of Ahmadiyya

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2015) |

After the death of Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, Noor-ud-Din was unanimously elected as his first successor. Among his achievements as Caliph were overseeing a satisfactory English translation of the Qur'an, the establishment in 1914 of the first Ahmadiyya Muslim mission in England and the introduction of various newspapers and magazines. After becoming Khalifa, he personally took part in two successful debates at the cities of Rampur and Mansouri. He sent various teams of scholars from Qadian to preach the Ahmadiyya message, to deliver lectures on Islam and hold sessions of religious discussion in numerous cities within India, which proved to be very successful for the community. These teams often included Khwaja Kamal-ud-Din, Mirza Mahmood Ahmad and Mufti Muhammad Sadiq.

The treasury

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2016) |

As Khalifatul Masih, Noor-ud-Din set up an official treasury (Baitul Maal) to cope with the growing financial requirements of the community. All the funds as well as the Zakat donations and other voluntary contributions were directed to be collected in the treasury. Various rules and regulations were given to govern its administration.

Public library

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2016) |

Noor-ud-Din was himself a man of learning and was fond of books. Soon after he became Khalifa, he set up a public library at Qadian, he donated many books from his own personal library and also gave some financial contributions towards it, followed by many other members of the community. The library was placed under the control of Mirza Mahmood Ahmad.

Friday prayers leave

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2016) |

In 1911 the British Government announced that a coronation ceremony will be held in Delhi to proclaim George V, Emperor of India. Noor-ud-Din requested the King that Muslim employees of the Government may be granted a leave of two hours on Friday for the Friday noon service. As a consequence two-hour leave for Muslim Employees was granted.

Mission in the UK

[edit]When Khwaja Kamal-ud-Din visited London in pursuance of his legal practice, Noor-ud-Din advised him to keep three things in view, one of which was to try to get the Mosque in Woking opened which was originally built by the Begum of Bhopal, and had been reported to have been locked for some time. Having reached London Kamaludin enquired about the mosque, met with other Muslims and was able to have the Woking Mosque unlocked.

Internal dissension

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2016) |

He also dealt with internal dissension, when some high-ranking office bearers of the Ahmadiyya Council disagreed with some of the administrative concepts being implemented and regarding the rights of a Caliph. After his death this group eventually left Qadian and made their headquarters in Lahore setting up their own association known as Ahmadiyya Anjuman Ishaat-i-Islam.[17][18]

Works

[edit]- Haqaiq al-furqan (four-volume compilation of Quranic discourses)

- Exegesis The Holy Qur’ân: Commentary & Reflections (based on his writings, translated by his daughter-in-law Amatul Rahman Omar with help from his son Abdul Mannan Omar)[19]

- Rahnuma-yi Hijaz al-mawsum bi-Riyaz al-haramayn (A Guide to the Hijaz, entitled the Gardens of Mecca and Medina), describing the holy places in Hijaz.

- Bayyaz-i-Noor-ud-Din (Noor-ud-Din's Pharmacopoeia)

- Faslul Khitab, fi Mas'ala-te Fatihah-til Kitab (on the importance of reciting the Fatiha during prayer behind an Imam)[20]

- Faslul Khitab, Muqaddimah Ahlul Kitab (two-volume response to Christian polemics against Islam)[21]

- Ibtal Uluhiyyat-i-Masih (Refutation of the Divinity of Christ)[22]

- Radd-i-Tanasukh (Refutation of the doctrine of Reincarnation)[23]

- Radd-i-Naskh-i- Qur'an (Refutation of the doctrine of Quranic Abrogation), comprising a series of correspondence with a Shia friend.

- Tasdeeq Barahin-e-Ahmadiyya (Verification of Barahin-e-Ahmadiyya), in response to Pandit Lekh Ram's takzeeb Barahin-e-Ahmadiyya.[24]

- Mirqatul-Yaqeen fi-hayaat-i-Noor-ud-Din (Autobiography)

- Deeniyat ka pehla rasala (Primer of Theology)

- Mabadi al-sarf wa Nahw (Principles of Grammar)

- Khutbat e-Noor (Collected Sermons)[25]

- Khitabat e Noor (Collected Speeches).[26]

- Eik Isai kei Tin Sawal aur unkei Jawabat (A Response to Three Questions of a Christian)[27]

- Irshadat e Noor (3-volume collection of letters, articles, announcements and Question & Answer Sessions).[28]

Marriages and children

[edit]

Noor-ud-Din married three times. His first wife was Fatima, daughter of Sheikh Mukarram Bhervi. She died in 1905, before he became Caliph. He also married Sughra Begum (1874 - 7 August 1955), the daughter of Sufi Ahmad Jan of Ludhiana in 1889. There is little information about his third wife. He likely married her during a visit to Mecca and Medina. Many of his children died in childhood.[29]

Noor-ud-Din had children with both his wives. With Fatima:

- Imamah (Died in 1897).

- Hafsah (1874 - )

- Amatullah

- Usamah

Two other daughters and eight other sons all died in infancy.[13]

With Sughra Begum, also known as Ammaji[13]

- Amatul Hayy (1 August 1901 - 10 December 1924), married Mirza Basheer-ud-Din Mahmood Ahmad

- Abdul Hayy (15 February 1999 - 11 November 1915)

- Abdus Salaam ( - 1956).

- Abdul Wahhaab

- Abdul Mannaan (19 April 1910 - 28 July 2006).

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Hakeem Noor-ud-Deen (Khalifatul Masih I): The Way of the Righteous" (PDF). Alislam.org. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- ^ "حضرت خلیفۃ المسیح الاولؓ کی عمر کے متعلق جدید تحقیق". 11 April 2020.

- ^ Ahmad 2003, pp. 84–5.

- ^ Friedmann 2003, pp. 14.

- ^ Friedmann 2003, pp. 15.

- ^ Ahmad 2003, p. 124.

- ^ Khan, Muhammad Zafrulla. "Hadrat Maulawi Nur-ud-Din: Khalifatul Masih I" (PDF). p. 1. Retrieved 19 April 2011.

- ^ Ahmad 2003, pp. 1–6.

- ^ Ahmad 2003.

- ^ "Hayat-e-Noor". Store.alislam.org. Archived from the original on 2 February 2016. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- ^ Ahmad 2003, pp. 31–2.

- ^ Abdul Kabir Dar. "AYUSH in J&K:- A Historical Perspective with special reference to Unani System of Medicine" (PDF). Medind.nic.in. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 September 2017. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- ^ a b c d Syed Hasanat Ahmad. "Hakeem Noor-Ud-Deen : The Way of the Righteous" (PDF). Alislam.org. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- ^ Al-Hakam (22 April 1908)

- ^ "Fasal-ul-Khitab Moqadama Ahl-ul-Kitab - Ahmadiyya Muslim Jama'at Urdu Pages". Alislam.org. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20070717214159/http://www2.alislam.org/pdf/mulfozaat.pdf. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 July 2007. Retrieved 21 February 2007.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Refuting the Qadiani beliefs". Ahmadiyya.org. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- ^ Hadrat Mirza Bashiruddin Mahmud Ahmad Khalifatul Masih II. "Truth about the Split" (PDF). Alislam.org. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- ^ Exegesis of The Holy Qur'ân, Commentary and Reflections (PDF). 2015. ISBN 978-1-942043-04-1. Retrieved 17 November 2024 – via islamusa.org.

- ^ Faslul Khitab, fi Mas'ala-te Fatihah-til Kitaab, Jammu, 1879

- ^ Ahmadiyya Muslim Community - Fasal-ul-Khitab Moqadama Ahl-ul-Kitab

- ^ Ibtal Uluhiyyat-i-Masih, Qadian, Zia ul Islam, 1904

- ^ Rudd-i-Tanasukh Archived 11 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, 1891

- ^ Tasdeeq Barahin-e-Ahmadiyya Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Qadian, 1890

- ^ Khutabat-i-Noor, (4th ed.), Qadian: nazaarat nashro ishaat, 2003

- ^ Khitabat e-Noor

- ^ Eik ‘Isai kei Tin Sawal aur unkei Jawabat, Anjuman Himayat-e-Islam, 1892

- ^ Irshadat e Noor

- ^ Ahmad 2003, p. 3.

References

[edit]- Ahmad, Syed Hasanat (2003). Hakeem Noor-ud-Deen: The Way of the Righteous (PDF). Surrey: Islam International. ISBN 1-85372-743-1.

- Friedmann, Yohanan (2003). Prophecy Continuous: Aspects of Ahmadi Religious Thought and its Medieval Background. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-566252-0.

External links

[edit]- Life Sketch of Maulana Hakeem Noor-ud-Din

- Quotes from Hakeem Noor-ud-Din

- Official Website of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community

- Official Website of the Lahore Ahmadiyya Movement for the Propagation of Islam Archived 20 August 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- Dawat-e-Lillah Articles - Ahmadiyya articles at eSnips both in Urdu and in English languages and as well as in Arabic

- Life of Mirza Ghulam Ahmad by Maulana Muhammad Ali

- Islamic Books Library @ Alislam.org - Alislam.org

- Real-islam.org