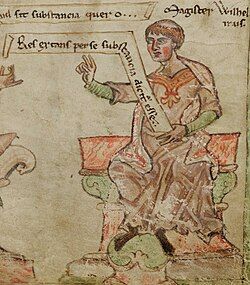

William of Conches

William of Conches (Latin: Gulielmus de Conchis; French: Guillaume de Conches; c. 1090 – c. 1154), historically sometimes anglicized as William Shelley,[1] was a medieval Norman-French scholastic philosopher who sought to expand the bounds of Christian humanism by studying secular works of classical literature and fostering empirical science. He was a prominent Chartrain (member of the School of Chartres). John of Salisbury, a bishop of Chartres and former student of William's, refers to William as the most talented grammarian of the time, after his former teacher Bernard of Chartres.

Life

[edit]

William was born around 1085[2]–1090[3] in a small village near Évreux, Normandy. From his surname, that village is generally taken to have been Conches[4] although it was possibly nearby Tilleul instead, the location of his later grave.[5][a] At the time, Normandy was still uneasily controlled by Norman England in notional homage to France. William studied under Bernard of Chartres in Chartres, Blois, and became a leading member of the School of Chartres, early Scholastics[4] who formed part of the 12th-century Renaissance. Less focused on Aristotle and medieval dialectic than Peter Abelard and his students at the University of Paris, the Chartrians primarily aimed to reconcile Christian morality and legend with Platonic philosophy, chiefly with reference to the Book of Genesis and Plato's Timaeus.[6]

William began teaching around 1115[2]–1120[1] and was primarily based in Paris and Chartres.[4][b] He composed his De Philosophia Mundi around the period 1125 to 1130.[8] He taught John of Salisbury at Chartres in 1137 and 1138, and John later considered him the most accomplished grammarian of his time[1] or just after his master Bernard.[c] John describes his method of teaching in detail, noting it followed Bernard and both followed Quintilian's Institutio Oratoria.[1] There were lectures on classical with questions on parsing, scansion, and composition. Students practiced writing prose and poetry on classical models and undertook frequent discussion on set subjects with the aim of developing fluency and cultivating elegant diction.[1] William of St. Thierry, who had previously encouraged Bernard of Clairvaux to prosecute Abelard, wrote another letter to the same cleric "on the errors of William of Conches" (De Erroribus Guillelmi de Conchis) in 1141,[8] complaining of the modalist view of the Trinity implicit in the Philosophia.[10] William had not explicitly upheld with Bernard Sylvestris that Plato's "world soul" (Latin: anima mundi; Ancient Greek: ψυχὴ τοῦ κόσμου, psychḕ toû kósmou) was essentially identical with the Holy Spirit, but had discussed the idea as a possibly valid reading.[11] With Abelard's writings successfully condemned by Bernard at the Council of Sens for a litany of heresies the same year, William withdrew from public teaching.[1] William's exemption from prosecution alongside his production of more orthodox revisions of some of his previous works, his departure from public teaching, and the bitterness of some of his discussion of clerics in his later works is suggestive of a compromise worked out between Bernard and his friend the papal legate Geoffroy de Lèves, who as bishop of Chartres would have overseen its affiliated school, but there is no explicit surviving record of such an arrangement.[12]

William then sought the patronage and protection of Geoffrey Plantagenet, the learned and powerful count of Anjou.[1] In 1143 or 1144, he became the personal tutor of Geoffrey's 9 to 11-year-old son Henry, later King Henry II of England. He also tutored Henry's brothers in the period from 1146 to 1149[13] and composed his Dragmaticon, a revision of his Philosophia in the form of a dialogue,[1] sometime between 1144 and 1149.[14] He dedicated it to Geoffrey.[1] There are some hints in his works that he may have resumed teaching, possibly in Paris, during the 1150s but these are inconclusive.[15]

He died in 1154[4] or shortly afterward,[3] probably at Paris or the environs of Évreux.[1] The funeral slab with his effigy has been moved from its original location at St Germanus's Church, Tilleul, to St Faith's Church in Conches.[5]

Works

[edit]The number and attribution of works by William of Conches has been a persistent problem of medieval bibliography,[16] as has the inaccuracy of the many manuscripts and editions.[17]

It is now certain that William wrote two editions of the encyclopedic De Philosophia Mundi ("On the Philosophy of the World"),[18] although it was previously variously attributed to Bede,[19] William of Hirsau,[20] Honorius of Autun,[21][22] and Hugh of St Victor.[23][24] Likewise, he wrote one edition of the related dialogue Dragmaticon,[18] whose neological name has been variously emended to Dramaticon ("A Dramatization")[16] and to Pragmaticon Philosophiae ("The Business of Philosophy")[4] although William himself understood his transliteration of dramatikón (δραματικόν) as meaning an interrogation (interrogatio) or question-and-answer format.[25][26] The Dragmaticon continues to be largely considered a bowdlerized or revised edition of the Philosophia; however, from the 1980s, scholars have reconsidered this attitude, noting that only about 3–5% of the earlier work was removed against a rough doubling of content, with numerous additional Greek and Arabic sources.[27] A "lost" treatise Magna de Naturis Philosophia ("The Great Philosophy of Nature"), considered his true masterwork by his early biographers and sometimes still attributed to him,[4] was the product of an extensive series of mistakes based on a poor edition of Vincent of Beauvais's Mirror of Nature[28] that began with an extract from William of Conches's work.[16]

William is also credited with numerous glosses on classic texts. He wrote surviving overviews of commentaries on Boethius's Consolation of Philosophy (Glosae super Boetium)[29] and Plato's Timaeus (Glosae super Platonem);[30] 2 editions of his own commentary on Priscian's Institutes of Grammar (Glosae super Priscianum); and one or two editions of commentary on Macrobius's Commentary on the Dream of Scipio (Glosae super Macrobium); his other works also mention now-lost commentaries on Martianus Capella's On the Marriage of Philology and Mercury and on Boethius's On Education in Music.[18] He was probably responsible for several surviving glosses of Juvenal's Satires and is credited by some with a lost commentary on Vergil's Aeneid.[18] He is sometimes still credited as the author of Moralium Dogma Philosophorum ("Philosophers' Moral Teachings"), the first medieval treatise on philosophical ethics,[4] although this attribution is more suspect.[31] The gloss of the Gospels (Glosa super Evangelia) credited to him was either entirely spurious or a misattribution of content from William of Auvergne.[31]

William's generally credited works are marked by special attention to cosmology and psychology and were among the first works of medieval Christian philosophy to devote considerable attention to Islamic philosophy and science, using the Latin translations produced by Constantine the African.[32] They display the humanism, Platonism, and affinity for the natural sciences of other members of the School of Chartres,[32] with whom William shared the tendency of analyzing his source texts through the lens of "covering" or "shieding" (integumentum) treating any apparent contradictions or heretical content within them as an allegory or metaphor for an underlying accurate and orthodox truth.[33] In the passage of Plato's Timaeus stating that souls existed in the stars before birth, William opined that he really meant "nothing heretical, but the most profound philosophy sheltered in the covering of the words". He then glossed Plato's intended meaning as simply noting the accepted importance of astrology on human fate.[33]

De Philosophia Mundi

[edit]William's chief work appears in manuscript as his Philosophy (Philosophia)[31] but, owing to mistakes in transmission and comprehension, various recensions were published for centuries as Bede's Four Books of the Philosophy of the Elements (Elementorum Philosophiae Libri Quatuor),[34][35][19] William of Hirsau's Three Books of Philosophical and Astronomical Instruction (Philosophicarum et Astronomicarum Institutionum Libri Tres),[20] and Honorius of Autun's Four Books on the Philosophy of the World (De Philosophia Mundi Libri Quatuor).[36][21] A separate recension rediscovered in the 20th century was a Compendium of Philosophy (Compendium Philosophiae) attributed to Hugh of St Victor.[23][24] The "Honorius" recension being the most complete,[22] it has become the general name for the work in modern scholarship.[4] The correct title and attribution were finally discovered in 1722 by Remi-Casimir Oudin[37] with additional points and considerations added by Charles Jourdain in 1838[38] and Jean-Barthélemy Hauréau in 1858.[39][40] It has also been known as William's Lesser Philosophy (Philosophia Minor)[41] by comparison with the misnamed, miscredited, and misdescribed Magna de Naturis Philosophia. More recently, Gregor Maurach produced partial and complete editions of the text compiled from numerous manuscripts[42][43][44] before it was fully realized that William had composed two separate editions, one during his youth and another revised around the time of Bernard's attacks on Abelard and others.[45] According to Paul Edward Dutton's tally, 68 manuscripts of the original edition and 16 of the revised edition are currently known to exist.[46][47]

The first edition of the De Philosophia Mundi was divided into four books,[48] covering physics, astronomy, geography, meteorology, and medicine. The revised edition expanded the first book and divided it into three parts, making up six books altogether.[48]

William glosses the composition of the world as rooted in the four elements but follows Constantine the African in considering an element "the simplest and minimum part of any body—simple in quality, minimum in quantity".[d] Therefore, he does not identify elemental fire, air, water, or earth with any of the composite forms in which they are experienced by humans.[e] He argues that the pure forms of the elements cannot be perceived but only grasped by reason applied to abstracted division of sensible forms.[f] He considers that these pure elements are defined by their intrinsic temperature and moistness: earth was cold and dry, water cold and moist, air hot and moist, and fire hot and dry. These traits compelled the atoms into certain movements, which he discusses in Aristotelian terms.[50] In his later Dragmaticon, he responds to reductio ad absurdum objections against the infinities implicit in atomism with his belief that the atoms are infinitely divisible only in the sense that they are too minuscule for human apprehension and infinitely numerous only in the sense that their number is—for humans—incalculably large.[51]

Discussing cosmology, William elaborates a geocentric universe.[52] The terrestrial atmosphere is said to become less dense and colder as altitude increases. Its circulation is also compared to ocean currents.[citation needed] By the level of the moon, it has been replaced by the ether;[53] with Plato, he considers this to be a form of fire rather than Aristotle's separate element.[54] The sun, moon, and five known planets followed their own motions while the fixed stars simply followed the motion of the ether itself.[53] William presented three arguments for the existence of God based on the order of the world.[50] He identified the parts of the Trinity with their attributes: God the Father as Power, Jesus the Son as Wisdom, and the Holy Spirit as Will or Goodness.[50] Unlike Abelard, he did not argue that God could not avoid creation but he did tend to limit the direct acts of God to creation, with angels otherwise intermediary between Heaven and this world.[50] However, his understanding of the physical world did prompt him to reject various parts of scripture, including that there is water in or beyond the heavens[55] or that Eve was created from Adam's rib.[56][54]

The discussion of medicine deals chiefly with procreation and childbirth. William's treatment here and in the Dragmaticon includes various medieval European and Arab misconceptions, such as explanations for why premature infants born in the 8th month of pregnancy (supposedly) invariably died while those born in the 7th month sometimes lived.[57] The supposed infrequency at which prostitutes gave birth was taken as evidence that pleasure was necessary for conception, while births from rape was then taken as proof that women derived carnal pleasure from the act despite their lack of rational consent.[57] This work influenced Jean de Meung, the author of the second part of the Roman de la Rose.[citation needed] William's discussion of psychology was expressed in terms of the soul, which he considered to provide various powers when joined to the body.[50] He believed that sense perception derived from the world, reason from God, and that memory preserved them both.[50]

Editions

[edit]- Philosophicarum et Astronomicarum Institutionum Guilielmi Hirsaugiensis Olim Abbatis Libri Tres [The Former Abbot William of Hirsau's Three Books of Philosophical and Astronomical Instruction] (in Latin), Basel: Heinrich Petri, 1531.

- "Honorii Augustudunensis Praesbyteri Liber Tertius de Philosophia Mundi" [On the Philosophy of the World, the Third Book of Honorius of Autun the Priest], D. Honorii Augustudunensis Presbyteri Libri Septem... [D. Honorius of Autun the Priest's Seven Books...] (in Latin), Basel: Heirs of Andreas Cratander, 1544, pp. 110–227.

- "Venerabilis Bedae Presbyteri Περὶ Διδάξεων sive Elementorum Philosophiae Libri Quatuor" [The Venerable Bede the Priest's Perì Didáxeōn or Four Books of the Philosophy of the Elements], Secundus Tomus Operum Venerabilis Bedae Presbyteri... [The Second Volume of the Works of the Venerable Bede the Priest...] (in Latin), Basel: Johann Herwagen Jr., 1563, pp. 311–342.

- Gratarolo, Guglielmo, ed. (1567), Dialogus de Substantiis Physicis ante Annos Ducentos Confectus a Vuilhelmo Aneponymo Philosopho... [A Dialogue on Physical Substances Composed 200 Years Ago by William Aneponymous a Philosopher] (in Latin), Strasbourg: Josias Ribel.

- "Περὶ Διδάξεων sive Elementorum Philosophiae Libri Quatuor" [Perì Didáxeōn or Four Books of the Philosophy of the Elements], Venerabilis Bedae Presbyteri Anglo-Saxonis Doctoris Ecclesiae Vere Illuminati Operum Tomus Secundus... [The Second Volume of the Works of the Venerable Bede, Anglo-Saxon Priest, Truly Enlightened Doctor of the Church...] (in Latin), Cologne: Johann Wilhelm Friessem Jr., 1688, pp. 206–343.

- Cousin, Victor, ed. (1836), "Appendix V... Commentaire d'Honoré d'Autun sur le Timée..." [Appendix V... Commentary of Honorius of Autun on the Timaeus...], Ouvrages Inédits d'Abélard... [Unedited Works by Abelard], Collection de Documents Inédits sur l'Histoire de France..., Deuxième Série: Histoire des Lettres et des Sciences [A Collection of Unedited Documents on the History of France... Second Series: History of Letters and Sciences] (in Latin), Paris: Royal Printing House, pp. 648–657.

- Migne, Jacques Paul, ed. (1850), "Περι Διδαξεων sive Elementorum Philosophiae Libri Quatuor" [Peri Didaxeōn or Four Books of the Philosophy of the Elements], Venerabilis Bedae Anglosaxonis Presbyteri Opera Omnia, Tomus Primus [The Complete Works of the Venerable Bede, Anglo-Saxon Priest, Vol. I], Patrologia Latina [Latin Patrology], Vol. 90 (in Latin), Paris: Ateliers Catholiques, cols. 1127–1178.

- Migne, Jacques Paul, ed. (1854), "De Philosophia Mundi Libri Quatuor" [Four Books on the Philosophy of the World], Honorii Augustodunensis Opera Omnia [The Complete Works of Honorius of Autun], Patrologia Latina [Latin Patrology], Vol. 172 (in Latin), Paris: Ateliers Catholiques, cols. 41–101.

- Migne, Jacques Paul, ed. (1854), "Commentarius in Timaeum Platonis Auctore ut Videtur Honorio Augustodunensi" [Commentary on Plato's Timaeus Apparently by the Author Honorius of Autun], Honorii Augustodunensis Opera Omnia [The Complete Works of Honorius of Autun], Patrologia Latina [Latin Patrology], Vol. 172 (in Latin), Paris: Ateliers Catholiques, cols. 245–252.

- Jourdain, Charles, ed. (1862), "Des Commentaires Inédits de Guillaume de Conches et de Nicolas Triveth sur La Consolation de la Philosophie de Boèce" [On the Unedited Commentaries of William of Conches and Nicholas Trivet on Boethius's Consolation of Philosophy], Notices et Extraits des Manuscrits de la Bibliothèque Impériale et Autres Bibliothèques... [Notices and Extracts of the Manuscripts of the Imperial Library and Other Libraries...], Vol. XX, Pt. 2 (in French and Latin), Paris: Imperial Printing House, pp. 40–82.

- Ottaviano, Carmelo, ed. (1935), Un Brano Inedito della Philosophia di Guglielmo di Conches [An Unpublished Excerpt from William of Conches's Philosophy] (in Latin), Naples: Alberto Morano.

- Parent, Joseph-Marie, ed. (1938), "Les Œuvres de Guillaume de Conches: Les Gloses de Guillaume de Conches sur La Consolation de Boèce & sur Le Timée" [The Works of William of Conches: The Gloses of William of Conches on the Consolation of Boethius & on the Timaeus], La Doctrine de la Création dans l'École de Chartres: Étude et Textes [The Doctrine of the Creation at the School of Chartres: Study and Texts], Publications de l'Institute d'Études Médiévales d'Ottawa [Publications of the Ottawa Institute of Medieval Studies], Vol. VIII (in French and Latin), Ottawa: Institute of Medieval Studies, pp. 115–177.

- Parra, Clotilde, ed. (1943), Guillaume de Conches et le Dragmaticon Philosophiae: Étude et Édition [William of Conches and the Dragmaticon of Philosophy: Study and Edition] (in Latin), Paris: National School of Charters.

- Delhaye, Philippe, ed. (1949), "L'Enseignement de la Philosophie Morale au XIIᵉ Siècle" [The Teaching of Moral Philosophy in the 12th Century], Mediaeval Studies (in French and Latin), vol. 11, Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, pp. 77–99, doi:10.1484/J.MS.2.305894.

- Jeauneau, Édouard, ed. (1957), "L'Usage de la Notion d'Integumentum à Travers les Gloses de Guillaume de Conches" [The Use of the Idea of Integumentum throughout the Glosses of William of Conches], Archives d'Histoire Doctrinale et Littéraire du Moyen Age [Archives of the Doctrinal and Literary History of the Middle Ages] (in French and Latin), vol. 24, Paris: Librairie Philosophique J. Vrin, pp. 35–100, JSTOR 44403077.

- Jeauneau, Édouard, ed. (1965), Glosae super Platonem [Glosses on Plato], Textes Philosophiques du Moyen Age [Philosophical Texts of the Middle Ages], Vol. XIII (in Latin), Paris: Librairie Philosophique J. Vrin, ISBN 2-7116-0336-9.

- Maurach, Gregor, ed. (1974), Philosophia Mundi: Ausgabe des 1. Buchs von Wilhelm von Conches' Philosophia... [The Philosophy of the World: Edition of the 1st Book of William of Conches's Philosophy] (in German and Latin), Pretoria: University of South Africa Press.

- Maurach, Gregor; et al., eds. (1974), "Guilelmi a Conchis Philosophiae Liber Tertius" [Book Three of William from Conches's Philosophy] (PDF), Acta Classica [Classical Acts], Vol. XVII (in Latin), Pretoria: Classical Association of South Africa, pp. 121–138.

- Maurach, Gregor; et al., eds. (1980), Philosophia [Philosophy], Studia [Studies], Vol. 16 (in Latin), Pretoria: University of South Africa Press.

- Wilson, Bradford, ed. (1980), Glosae in Iuvenalem [Glosses on Juvenal] (in Latin), Paris: Vrin.

- Ronca, Italo, ed. (1997), Guillelmi de Conchis Dragmaticon [William of Conches's Dragmaticon], Corpus Christianorum Continuatio Mediaevalis, Vol. 152 (in Latin), Turnhout: Brepols, ISBN 2-503-04522-7.

- Ronca, Italo; et al., eds. (1997), A Dialogue on Natural Philosophy (Dragmaticon Philosophiae), Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press.

- Nauta, Lodi, ed. (1999), Guillelmi de Conchis Glosae super Boetium [William of Conches's Glosses on Boethius], Corpus Christianorum Continuatio Mediaevalis, Vol. 158 (in Latin), Turnhout: Brepols, ISBN 2-503-04582-0.

- Jeauneau, Édouard, ed. (2006), Glosae super Platonem [Glosses on Plato], Corpus Christianorum Continuatio Mediaevalis, Vol. 203 (in Latin) (Rev. ed.), Turnhout: Brepols.

- Albertazzi, Marco, ed. (2010), Philosophia [Philosophy] (in Latin), Lavis: La Finestra, ISBN 978-88-95925-13-4.

- Martello, Concetto, ed. (2011), Platone a Chartres: Il Trattato sull'Anima del Mondo di Guglielmo di Conches [Plato at Chartres: William of Conches's Treatise on the World Soul], Machina Philosophorum, Vol. 25 (in Italian and Latin), Palermo: Officina di Studi Medievali.

- Martello, Concetto, ed. (2012), Anima e Conoscenza in Guglielmo di Conches [Soul and Consciousness in William of Conches] (in Italian and Latin), Catania: Cooperativa Universitaria Editrice Catanese di Magistero.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ William's birth was placed in Cornwall by John Bale on the supposed authority of John Boston of Bury St Edmunds Abbey, although Mary Bateson and others have considered this implausible.[1]

- ^ He has sometimes been identified as the "Guillaume de Conques" listed as born 1080 and died 1154 who figures in the list of faculty of the medical school of the University of Montpellier, although this remains a minority opinion.[7]

- ^ ... Willelmus de Conchis, grammaticus, post Bernardum Carnotensem, opulentissimus ...[9]

- ^ Elementum ergo, ut ait Constantinus in Pantegni, est simpla et minima pars alicuius corporis—simpla ad qualitatem, minima ad quantitatem.[49]

- ^ Si ergo illis digna velimus imponere nomina, particulas praedictas dicamus "elementa", ista quae videntur "elementata".[49]

- ^ Quae elementa numquam videntur, sed ratione divisionis intelliguntur.[49]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k DNB (1900).

- ^ a b Ferrara (2016), p. 13.

- ^ a b Ramírez-Weaver (2009), p. 1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Brit. (2024).

- ^ a b Ferrara (2016), pp. 2–3.

- ^ Parra (1943), p. 178.

- ^ Ferrara (2016), p. 14.

- ^ a b Ramírez-Weaver (2009), p. 8.

- ^ Migne (1855), col. 832.

- ^ Anderson (2016), p. 169.

- ^ Adamson (2019), p. 97.

- ^ Ferrara (2016), pp. 26–28.

- ^ Ferrara (2016), p. 10.

- ^ Ferrara (2016), p. 9.

- ^ Ferrara (2016), p. 33.

- ^ a b c Poole (1920), Appendix VI: Excursus on the Writings of William of Conches.

- ^ Jeauneau (1973), pp. 23–24.

- ^ a b c d Ferrara (2016), p. 35.

- ^ a b Migne (1850).

- ^ a b Petri (1531).

- ^ a b Migne, Phil. Mundi (1854).

- ^ a b Poole (1920), Appendix V: Excursus on a Supposed Anticipation of Saint Anselm.

- ^ a b Ottaviano (1935).

- ^ a b Ferrara (2016), pp. 39–41.

- ^ Glosae super Priscianum, p. 10.

- ^ Ferrara (2016), p. 49.

- ^ Ferrara (2016), pp. 43–48.

- ^ Ferrara (2016), pp. 35–36.

- ^ Jourdain (1862); Parent (1938); & Lodi (1999).

- ^ Cousin (1836); Migne, Comm. Tim. (1854); Parent (1938) & Jeauneau (1957), pp. 88–100; Delhaye (1949), pp. 95–96; Jeauneau (1965); Jeauneau (2006); Martello (2011); & Martello (2012).

- ^ a b c Ferrara (2016), p. 36.

- ^ a b Cath. Enc. (1913).

- ^ a b Adamson (2019), p. 96.

- ^ Herwagen (1563).

- ^ Friessem (1688).

- ^ Cratander (1544).

- ^ Oudin (1722), col. 1230.

- ^ Jourdain (1838), pp. 101–104.

- ^ Hauréau (1858), cols. 668–670.

- ^ Ferrara (2016), pp. 36–37.

- ^ Ferrara (2016), p. 37.

- ^ Maurach, Phil. Mundi (1974).

- ^ Maurach, Acta Cl. (1974).

- ^ Maurach & al. (1980).

- ^ Ferrara (2016), pp. 38–39.

- ^ Dutton (2006), pp. 37–39.

- ^ Dutton (2011), pp. 477–485.

- ^ a b Parra (1943), p. 177.

- ^ a b c De Philosophia Mundi, Book I, Ch. 22.

- ^ a b c d e f Parra (1943), p. 179.

- ^ Adamson (2019), p. 99.

- ^ Parra (1943), pp. 179–180.

- ^ a b Parra (1943), p. 180.

- ^ a b Adamson (2019), pp. 99–100.

- ^ Genesis 1:6–8

- ^ Genesis 2:21–22

- ^ a b Adamson (2019), pp. 100.

Bibliography

[edit]- "William of Conches", Britannica, Chicago: Britannica Group, 2024.

- Adamson, Peter (2019), Medieval Philosophy, A History of Philosophy without Any Gaps, Vol. 4, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-884240-8.

- Anderson, Ross Matthew (2016), The Effect of Factionalism on Jewish Persecution: How the Conflict between Bernard of Clairvaux's Cistercian Order and Peter Abelard's Scholasticism Contributed to the Equating of Jews with Heretics, Raleigh: North Carolina State University.

- Bateson, Mary (1900). "William of Conches". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Dutton, Paul Edward (2006), The Mystery of the Missing Heresy Trial of William of Conches, Étienne Gilson Series, Vol. 28, Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, ISBN 9780888447289, ISSN 0708-319X.

- Dutton, Paul Edward (2011), "The Little Matter of a Title: Philosophia Magistri Willelmi de Conchis [The Philosophy of Master William of Conches]", Guillaume de Conches: Philosophie et Science au XIIᵉ Siècle [William of Conches: Philosophy and Science in the 12th Century], Micrologus Library, Vol. 42, Florence: SISMEL-Edizioni del Galluzzo.

- Ellard, Peter Charles (2007), The Sacred Cosmos: Theological, Philosophical, and Scientific Conversations in the Twelfth Century School of Chartres, Scranton: University of Scranton Press, ISBN 9781589661332.

- Ferrara, Carmine (2016), Guglielmo di Conches e il Dragmaticon Philosophiae [William of Conches and the Dragmaticon Philosophiae] (in Italian), Fisciano: University of Salerno.

- Hauréau, Jean-Barthélemy (1858), "Guillaume de Conches" [William of Conches], Nouvelle Biographie Générale... [New General Biography...], Vol. 28 (in French), Paris: Firmin Didot Bros., cols. 667–673.

- Jeauneau, Édouard (1973), Lectio Philosophorum: Recherches sur l'École de Chartres [Selections of the Philosophers: Research into the School of Chartres] (in French and Latin), Amsterdam: Adolf M. Hakkert, ISBN 90-256-0606-7.

- John of Salisbury (1855), "Metalogicus", Joannis Cognomine Saresberiensis Carnotensis Episcopi Opera Omnia [The Complete Works of John of Salisbury, Bishop of Chartres], Patrologia Latina [Latin Patrology], Vol. 199 (in Latin), Paris: Ateliers Catholiques.

- Jourdain, Charles (1838), Dissertation sur l'État de la Philosophie Naturelle en Occident et Principalement en France pendant la Première Moitié du XIIᵉ Siècle [Dissertation on the State of Natural Philosophy in the West and Principally in France during the First Half of the 12th Century] (in French), Paris: Firmin Didot Bros.

- Oudin, Remi-Casimir (1722), Commentarius de Scriptoribus Ecclesiae Antiquis [Commentary on the Writers of the Ancient Church] (in Latin), vol. II, Leipzig & Frankfurt: Moritz Georg Weidmann.

- Poole, Reginald Lane (1920), Illustrations of the History of Medieval Thought and Learning (2nd ed.), London: Richard Clay & Sons.

- Ramírez-Weaver, Eric M. (2009), "William of Conches, Philosophical Continuous Narration, and the Limited Worlds of Medieval Diagrams", Studies in Iconography, vol. 30, Kalamazoo: Western Michigan University, pp. 1–41, JSTOR 23924339.

- Turner, William (1913). "William of Conches". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

External links

[edit]- Philosophia Mundi [The Philosophy of the World], Book I (in Latin) & Moralium Dogma Philosophorum [Philosophers' Teachings of Morality] (in Latin) at the Latin Library

- MS ljs384: De Philosophia Mundi, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 1100s.