Clio Awards

| Clio Awards | |

|---|---|

The Clio Awards logo | |

| Awarded for | Creative excellence in advertising and design |

| Country | Worldwide |

| Presented by | Evolution Media |

| Established | 1959 |

| First awarded | 1960 |

| Website | clios.com |

The Clio Awards, also simply known as The Clios, is an annual award program that recognizes innovation and creative excellence in advertising, design, and communication, as judged by an international panel of advertising professionals. The awards are presented by Evolution Media.

The Clios has several awards programs alongside the larger Clio Awards that recognize creative marketing efforts in specific industries: Clio Cannabis, Clio Entertainment, Clio Fashion & Beauty, Clio Health, Clio Music, and Clio Sports. One work in each media type may be awarded the Grand Clio, the highest honor.

Time magazine, in 1991, described the event as the world's most recognizable international advertising awards.

History

[edit]The awards, founded by Wallace A. Ross in 1959, are named for the Greek goddess Clio, the mythological Muse known as "the proclaimer, glorifier and celebrator of history, great deeds and accomplishments."[1]

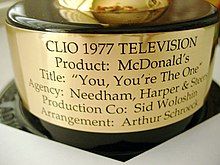

Originally presented by the American Radio and TV Commercials Festival, the parent company for the Clios, also founded and directed by Ross,[2] the first Clios were awarded in 1960 for excellence in U.S. television advertising. Each winner received a gold Georg Olden–designed statuette. The competition was expanded to include work on international television and cinema in 1966, and then U.S. radio ads in 1967.[1]

1970s–1980s

[edit]

The Clio Awards were acquired by Bill Evans in 1971 for US$150,000[3] (equivalent to $1,092,601 in 2023) and became a "for profit" company.[1] Over the next two decades the company's income grew to $2.5 million per year, derived primarily from Clio nomination fees, of $70 to $100 per entry.[4]

Evans expanded competition by including U.S. print advertising in 1971, international print advertising in 1972, international radio advertising in 1974, U.S. packaging design in 1976, international packaging design and U.S. specialty advertising in 1977, U.S. cable in 1983, and Hispanic competition in 1987.[1]

The rules for the 1984 award required that a given entry appear publicly during the calendar year in 1983. In order to be eligible, Chiat/Day needed to run Apple Computer's "1984" commercial (directed by Ridley Scott) for the Macintosh computer prior to Super Bowl XVIII. In December 1983, Apple purchased time on KMVT in Twin Falls, Idaho, after the normal sign-off, and recorded the broadcast in order to qualify.[5]

In 1984, a nearly identical situation occurred when Doyle Dane Bernbach, the ad agency for Ziebart, purchased time on a Detroit channel carrying the inaugural Cherry Bowl college football game in December in order for Ziebart's "Friend of the Family (Rust in Peace)" commercial to be eligible for the awards the following year. The commercial won the Clio Award in 1985.[6]

The 1988 awards were aired on television on FOX and hosted by David Leisure on December 7, 1988.[7]

1990s

[edit]1991 Clio Awards

[edit]Attendees of the 1991 Clio Awards who had paid the $125 admission price did not have tickets waiting at the door, as promised. Also missing was Clio President Bill Evans.

The caterer of the event announced that the master of ceremonies was considered a no-show, but that he would attempt to stand in as the host. He informed the audience that the winners list had been lost. Print ads were the first awards; transparencies of the winning entries were displayed, sometimes backwards or out of focus. As each image appeared on screen, the owner of the work was asked to come to the stage, pick up their Clio, and identify themselves and their agency. Eventually, advertising executives, intent on the Clios that remained, rushed the stage and grabbed any that had not been claimed.[4][3]

The event for television commercials, scheduled a few days later, was called off.[4][3]

1992 bankruptcy

[edit]On March 17, 1992, Clio Enterprises Inc., filed for bankruptcy, claiming $1.8 million in debts and indeterminate assets of at least $1 million.[8] Chicago publisher Ruth Ratny purchased the Clio name for an undisclosed figure. Evans had wanted $2 million, and trade publications reported a sale price of $10,000, which Ratny called low. Ratny reorganized the event as the New Clio Awards, and combined what had previously been two events into a single presentation, which was delayed from June until September 1992. Advertising Age magazine reported 6,000 entries, less than one quarter of the 1990 total. As a concession to the 1991 winners who had not yet received the trophies, their entry fee was waived. The 1990 award show at the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts drew 1,800, while only 500 paid for the 1992 show at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel,[3] which was hosted by Tony Randall. A total of 86 awards in 73 categories were handed out.[9] Another major change with the "New" Clios was direct competition between U.S. and foreign firms, which resulted in Swiss agency Comsult/Advico Young & Rubicam being named the winner of the best Television campaign.[10]

A bankruptcy court ruled that the creditors of the 1991 Clio Awards should be paid. At the time, Ratny lacked the financial resources to settle the $600,000 debt. Another Chicagoan, former film editor James M. Smyth, put up the money and became sole owner of the Clio Awards. On New Year's Eve of 1992, Smyth began working on the 1993 show.[11][12] The award ceremony was again delayed until September, and Jay Chiat of TBWA\Chiat\Day, Rick Fizdale from Leo Burnett Worldwide and Keith Reinhard at DDB Worldwide joined the Clio Executive Committee.[13]

In 1997, the Clios were sold to Dutch-owned company VNU Media;[4] Andrew Jaffe at Adweek managed the acquisition.[14]

2000s

[edit]In 2007, VNU changed its name to the Nielsen Company.[4]

In 2009, e5 Global Media assumed control of Clio, when it acquired magazines Adweek and Billboard, among others, from Nielsen Business Media.[15][unreliable source?]

In 2010, Nicole Purcell was appointed executive director of Clio and Brooke Levy was hired to run marketing for the organization. In 2015, Purcell was promoted to president.[16]

In 2014, the Clio Awards absorbed The Hollywood Reporter's Key Art Awards (created in 1971 by Tichi Wilkerson) to celebrate marketing and communications in the entertainment business. In 2017, it was renamed the Clio Entertainment Award.[17][18]

In 2020, the Clios were postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[17]

Description

[edit]The Clios are an annual award program that recognizes innovation and creative excellence in advertising, design, and communication, as judged by an international panel of advertising professionals.[19][20]

Judging

[edit]In 2007, Clio stated that the competition received more than 19,000 entries from all over the world and enlisted a jury of more than 110 judges from 62 countries. Nearly two-thirds of the submissions came from outside the United States.[citation needed]

In 2014, Clio assembled a 50/50 male-female jury, of which 75% were international (non-US) judges.[citation needed] 2014 was also the year Clio began holding judging sessions internationally. The 2014 session took place in Malta, and the 2015 session in Tenerife, Spain.

According to the Clio Awards website, more than 80% of submissions are eliminated within the first two rounds. Juries then determine whether a work deserves to be included on the Shortlist, or receive a Bronze, Silver, or Gold medal. One work in each media type may be awarded the Grand Clio, the highest honor.[citation needed]

Awards programs and subsidiaries

[edit]Programs

[edit]- Clio Cannabis – recognizes excellence in marketing and communications in the cannabis industry. The program was launched in 2019.[21]

- Clio Entertainment – recognizes excellence in marketing and communications across film, television, live entertainment, and gaming. This award originates from The Hollywood Reporter's Key Art Awards, which was created in 1971 by Tichi Wilkerson and acquired by Clio in 2014. The award received its current name in 2017.[17][18] Being postponed in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the ceremony returned in 2021, where voiceover artist Tom Kane received an honorary Clio Entertainment Award.[17]

- Clio Fashion & Beauty – recognizes excellence in marketing and communications the industries of fashion/style and cosmetics. This program was introduced in 2013.[22]

- Clio Health – recognizes excellence in marketing and communications in health and wellness.[23]

- Clio Music – recognizes excellence in marketing and communications in the music industry. This program was introduced in 2014.[24]

- Clio Sports – recognizes excellence in sports advertising and marketing. This program was founded in 2014.[25]

Subsidiaries

[edit]- Ads of The World – Clio's global ad archive.

- Muse by Clio – Clio's content platform. Muse is a news site and newsletter that covers "the best in creativity in advertising and beyond." Its coverage includes creative efforts in brand marketing, fashion, film and TV, gaming, healthcare, music, and sports. The publication is claims to be editorially independent from the Clio Awards, with its coverage not being "connected in any way to [its] parent company's award programs."[26]

Recognition and status

[edit]In 1991 Time magazine described the event as the world's most recognizable international advertising awards.[4]

Archive

[edit]In 2017, the Indiana University Libraries Moving Image Archive acquired the Clio Awards Collection from the London International Awards, the organization that purchased the collection from the Clio organization in 1992.[27] Composed of thousands of reels of 16 mm and 35 mm film, the collection contains Clio entries and winners from the 1960s through the early 1990s across a wide variety of categories.[28] International submissions are also included in the collection.[27]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Carder, Sheri: "Clio Awards" The Guide to United States popular culture, pages 180-181, ISBN 978-0-87972-821-2

- ^ "Meet Wallace A. Ross," by Kaplan; Back Stage Magazine, 1964; pages 4-5.

- ^ a b c d Horovitz, Bruce (September 4, 1992). "Hello Clio, What's New? : Advertising Executives Slow to Welcome Reincarnated Award Ceremony". LA Times. Archived from the original on March 15, 2012. Retrieved August 4, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f "Advertising The Collapse Of Clio". Time. July 1, 1991. Archived from the original on November 22, 2010. Retrieved August 5, 2021.

- ^ Linzmayer, Owen (1994). The Mac Bathroom Reader. Sybex, ISBN 978-0-7821-1531-4

- ^ "What's Wrong With Detroit Now". Detroit Free Press. August 26, 1985. Archived from the original on August 19, 2016. Retrieved July 3, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ O'Connor, John J. (December 7, 1988). "Review/Television; Special Offer: The Clio Candidates". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 25, 2015. Retrieved August 5, 2021.

- ^ Elliott, Stuart (March 18, 1992). "Bankruptcy Filing By Clio Enterprises". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 2, 2016. Retrieved August 4, 2021.

- ^ Elliott, Stuart (September 14, 1992). "'New' Clios Face a Test Of Credibility". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 2, 2016. Retrieved August 4, 2021.

- ^ Horovitz, Bruce (September 16, 1992). "Swiss Firm Wins Top Clio Award". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 3, 2012. Retrieved August 5, 2021.

- ^ Millman, Nancy (February 22, 1993). "Tempo reported on the New Clio Awards". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on June 14, 2012. Retrieved August 5, 2021.

- ^ Feigenbaum, Nancy (February 1, 1993). "The Clio Awards is about to get yet". Orlando Sentinel. Archived from the original on June 28, 2010. Retrieved August 5, 2021.

- ^ Elliot, Stuart (May 28, 1993). "Another Setback For Clio Awards". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 18, 2018. Retrieved August 5, 2021.

- ^ Elliott, Stuart (March 6, 2010). "Andrew Jaffe, Who Brought Clios to Adweek, Is Dead at 71". The New York Times. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

- ^ Kelly, Keith J. (May 23, 2010). "CLIO awards return to downtown just as advertised". New York Post. Archived from the original on May 26, 2015. Retrieved August 5, 2021.

- ^ "Nicole Purcell Named President of CLIO". The Hollywood Reporter. January 20, 2015. Archived from the original on August 5, 2021. Retrieved August 5, 2021 – via Yahoo Sports.

- ^ a b c d Chagollan, Steve (December 13, 2021). "Clio Entertainment Awards Ensure Marketing's "Unsung Heroes" Their Moment in the Sun". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved March 27, 2022.

- ^ a b "Program Home". Clios. Retrieved March 27, 2022.

- ^ Riordan, Steve (1989). Clio Awards: A Tribute to 30 Years of Advertising Excellence 1960-1989, Part 1. PBC International. ISBN 0-86636-124-3.

- ^ "About Clio". Clios. September 8, 2016. Retrieved October 14, 2024.

- ^ "About • Clio Cannabis". www.cliocannabisawards.com. Retrieved March 27, 2022.

- ^ "Clio Fashion & Beauty". Clios. Retrieved March 27, 2022.

- ^ "Clio Health". Clios. Retrieved March 27, 2022.

- ^ "Clio Music". Clios. Retrieved March 27, 2022.

- ^ "Clio Sports". Clios. Retrieved March 27, 2022.

- ^ "About Us". Muse by Clio. Retrieved March 27, 2022.

- ^ a b "IU Libraries Moving Image Archive is the new home for decades of award-winning commercials". News at IU Bloomington. December 14, 2017. Archived from the original on April 6, 2018. Retrieved August 5, 2021.

- ^ "Clio Awards Collection · Indiana University Libraries Moving Image Archive". collections.libraries.indiana.edu. Archived from the original on April 20, 2018. Retrieved April 19, 2018.