Gomphothere

| Gomphothere Temporal range: Late Oligocene - Holocene

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Specimen of Gomphotherium productum at the American Museum of Natural History | |

| |

| Notiomastodon platensis Centro Cultural del Bicentenario de Santiago del Estero in Argentina | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Proboscidea |

| Superfamily: | †Gomphotherioidea |

| Family: | †Gomphotheriidae (Hay, 1922) A. Cabrera 1929 |

| Genera | |

| |

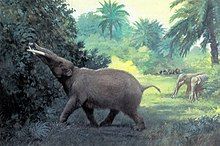

Gomphotheres are an extinct group of proboscideans related to modern elephants. First appearing in Africa during the Oligocene, they dispersed into Eurasia and North America during the Miocene and arrived in South America during the Pleistocene as part of the Great American Interchange. Gomphotheres are a paraphyletic group ancestral to Elephantidae, which contains modern elephants, as well as Stegodontidae.

While most famous forms such as Gomphotherium had long lower jaws with tusks, the ancestral condition for the group, some later members developed shortened (brevirostrine) lower jaws with either vestigial or no lower tusks and outlasted the long-jawed gomphotheres. This change made them look very similar to modern elephants, an example of parallel evolution. During the Pliocene and Early Pleistocene, the diversity of gomphotheres declined, ultimately becoming extinct outside of the Americas. The last two genera, Cuvieronius ranging southern North America to western South America, and Notiomastodon ranging over most of South America, continued to exist until the end of the Pleistocene around 12,000 years ago, when they became extinct along with many other megafauna species following the arrival of humans.

The name "gomphothere" comes from Ancient Greek γόμφος (gómphos), "peg, pin; wedge; joint" plus θηρίον (theríon), "beast".

Description

[edit]

Gomphotheres differed from elephants in their tooth structure, particularly the chewing surfaces on the molar teeth. The teeth are considered to be bunodont, that is, having rounded rather than sharp cusps.[1] They are thought to have chewed differently from modern elephants, using an oblique movement (combining back to front and side to side motion) over the teeth rather than the proal movement (a forwards stroke from the back to the front of the lower jaws) used by modern elephants and stegodontids,[2] with this oblique movement being combined with vertical (orthal) motion that served to crush food.[3] Like modern elephants and other members of Elephantimorpha, gomphotheres had horizontal tooth replacement, where teeth would progressively migrate towards the front of the jaws before they were taken place by more posterior teeth. Unlike modern elephants, many gomphotheres retained permanent premolar teeth[4] though they were absent in some gomphothere genera.[5]

-

Largely unworn molar of Gomphotherium angustidens, a "trilophodont gomphothere"

-

Worn molar of Gomphotherium angustidens

-

Lower jaw of Gomphotherium angustidens (bottom) showing elongate mandibular symphysis and lower tusks at their tips

-

Molar of a modern African elephant (Loxodonta) for comparison

Early gomphotheres had lower jaws with an elongate (longitostrine) mandibular symphysis (the front-most part of the lower jaw) and lower tusks, the primitive condition for members of Elephantimorpha. Later members developed shortened (brevirostrine) lower jaws and/or vestigial or no lower tusks, a convergent process that occurred multiple times among gomphotheres, as well as other members of Elephantimorpha.[5] In Gomphotheriidae, these elongate mandibular symphysis tend to be narrow, while the lower tusks tend to be club shaped.[6] While the musculature of the trunk of longirostrine gomphotheres was likely very similar to that of living elephants, the trunk was likely shorter (probably no longer than the tips of the lower tusks), and rested upon the elongate lower jaw, though the trunks of later brevirostrine gomphotheres were likely free hanging and comparable to those of living elephants in length.[3] The lower tusks and long lower jaws of primitive gomphotheres were likely used for cutting vegetation, with a secondary contribution in acquiring food using the trunk, while brevirostrine gomphotheres relied primarily on their trunks to acquire food similar to modern elephants.[6] The upper tusks of primitive longirostrine gomphotheres typically gently curve downwards,[3] and generally do not exceed 2 metres (6.6 ft) in length and 35 kilograms (77 lb) in weight,[7] though some later brevirostine gomphotheres developed considerably larger upper tusks.[3][7] Upper tusks of brevirostine gomphotheres include those which are straight[3] and upwardly curved.[8]

Most gomphotheres reached sizes equivalent to those of those of the modern Asian elephant (Elephas maximus), though some gomphotheres reached sizes comparable to or somewhat exceeding African bush elephants (Loxodonta africana).[9] The limb bones of gomphotheres like those of mammutids are generally more robust than elephantids, with the legs also tending to be proportionally shorter. Their bodies also tend to be more proportionally elongate than those of living elephants.[10]

Taxonomy

[edit]"Gomphotheres" are assigned to their own family, Gomphotheriidae, but are widely agreed to be a paraphyletic group. The families Choerolophodontidae and Amebelodontidae (the latter of which includes "shovel tuskers" with flattened lower tusks like Platybelodon) are sometimes considered gomphotheres sensu lato,[11][12][13] though some authors argue that Amebelodontidae should be sunk into Gomphotheriidae.[14] Gomphotheres are divided into two informal groups, "trilophodont gomphotheres", and "tetralophodont gomphotheres". "Tetralophodont gomphotheres" are distinguished from "trilophodont gomphotheres" by the presence of four ridges on the fourth premolar and on the first and second molars, rather than the three present in trilophodont gomphotheres.[11] Some authors choose to exclude "tetralophodont gomphotheres" from Gomphotheriidae, and instead assign them to the group Elephantoidea.[11] "Tetralophodont gomphotheres" are thought to have evolved from "trilophodont gomphotheres", and are suggested to be ancestral to Elephantidae, the group which contains modern elephants, as well as Stegodontidae.[15]

While the North American long jawed proboscideans Gnathabelodon, Eubelodon and Megabelodon been assigned to Gomphotheriidae in some studies[5][16] other studies suggest that they should be assigned to Amebelodontidae (Eubelodon, Megabelodon) or Choerolophodontidae (Gnathabelodon).[6]

Cladogram of Elephantimorpha after Li et al. 2023, showing a paraphyletic Gomphotheriidae.[6]

| Elephantimorpha |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ecology

[edit]Gomphotheres are generally supposed to have been flexible feeders, with the various species having differing browsing, mixed feeding and grazing diets, with the dietary preference of individual species and populations being shaped by local factors such as climatic conditions and competition.[17] Analysis of the tusks of a male Notiomastodon individual suggest that it underwent musth, similar to modern elephants.[18] Notiomastiodon is also suggested to have lived in social family groups, like modern elephants.[19]

Evolutionary history

[edit]Gomphotheres originated in Afro-Arabia during the mid-Oligocene, with remains from the Shumaysi Formation in Saudi Arabia dating to around 29-28 million years ago. Gomphotheres were uncommon in Afro-Arabia during the Oligocene.[20] Gomphotheres arrived in Eurasia after the connection of Afro-Arabia and Eurasia during the Early Miocene around 19 million years ago,[21] in what is termed the "Proboscidean Datum Event". Gomphotherium arrived in North America around 16 million years ago,[22] and is suggested to be the ancestor of later New World gomphothere genera.[23] "Trilophodont gomphotheres" dramatically declined during the Late Miocene, likely due to the increasing C4 grass-dominated habitats,[21] while during the Late Miocene "tetralophodont gomphotheres" were abundant and widespread in Eurasia, where they represented the dominant group of proboscideans.[24] All trilophodont gomphotheres, with the exception of the Asian Sinomastodon, became extinct in Eurasia by the beginning of the Pliocene,[25] along with the global extinction of the "shovel tusker" amebelodontids.[26] The last gomphotheres in Africa, represented by the "tetralophodont gomphothere" genus Anancus, became extinct around the end of the Pliocene and beginning of the Pleistocene.[27] The New World gomphothere genera Notiomastodon and Cuvieronius dispersed into South America during the Pleistocene, around or after 2.5 million years ago as part of the Great American Biotic Interchange due to the formation of the Isthmus of Panama, becoming widespread across the continent.[28] The last gomphothere native to Europe, Anancus arvernensis[29] became extinct during the Early Pleistocene, around 1.6–2 million years ago[30][31] Sinomastodon became extinct at the end of the Early Pleistocene, around 800,000 years ago.[32] From the latter half of the Early Pleistocene onwards, gomphotheres were extirpated from most of North America, likely due to competition with mammoths and mastodons.[17]

The extinction of gomphotheres in Afro-Eurasia has generally been supposed to be the result the expansion of Elephantidae and Stegodon.[25][33] The morphology of elephantid molars being more efficient than gomphotheres in consuming grass, which became more abundant during the Pliocene and Pleistocene epochs.[33] In southern North America, Central America and South America, gomphotheres did not become extinct until shortly after the arrival of humans to the Americas, approximately 12,000 years ago, as part of the Late Pleistocene megafauna extinctions of most large mammals across the Americas. Bones of the last gomphothere genera, Cuvieronius and Notiomastodon, dating to shortly before their extinction have been found associated with human artifacts, suggesting that hunting may have played a role in their extinction.[28]

References

[edit]- ^ Buckley, Michael; Recabarren, Omar P.; Lawless, Craig; García, Nuria; Pino, Mario (November 2019). "A molecular phylogeny of the extinct South American gomphothere through collagen sequence analysis". Quaternary Science Reviews. 224: 105882. Bibcode:2019QSRv..22405882B. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2019.105882.

- ^ Saegusa, Haruo (March 2020). "Stegodontidae and Anancus: Keys to understanding dental evolution in Elephantidae". Quaternary Science Reviews. 231: 106176. Bibcode:2020QSRv..23106176S. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2020.106176. S2CID 214094348.

- ^ a b c d e Nabavizadeh, Ali (2024-10-08). "Of tusks and trunks: A review of craniofacial evolutionary anatomy in elephants and extinct Proboscidea". The Anatomical Record. doi:10.1002/ar.25578. ISSN 1932-8486. PMID 39380178.

- ^ Sanders, William J. (2018-02-17). "Horizontal tooth displacement and premolar occurrence in elephants and other elephantiform proboscideans". Historical Biology. 30 (1–2): 137–156. Bibcode:2018HBio...30..137S. doi:10.1080/08912963.2017.1297436. ISSN 0891-2963.

- ^ a b c Mothé, Dimila; Ferretti, Marco P.; Avilla, Leonardo S. (12 January 2016). "The Dance of Tusks: Rediscovery of Lower Incisors in the Pan-American Proboscidean Cuvieronius hyodon Revises Incisor Evolution in Elephantimorpha". PLOS ONE. 11 (1): e0147009. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1147009M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0147009. PMC 4710528. PMID 26756209.

- ^ a b c d Li, Chunxiao; Deng, Tao; Wang, Yang; Sun, Fajun; Wolff, Burt; Jiangzuo, Qigao; Ma, Jiao; Xing, Luda; Fu, Jiao (2023-11-28), "The trunk replaces the longer mandible as the main feeding organ in elephant evolution", eLife, 12, doi:10.7554/eLife.90908.1, retrieved 2024-05-29

- ^ a b Larramendi, Asier (2023-12-10). "Estimating tusk masses in proboscideans: a comprehensive analysis and predictive model". Historical Biology: 1–14. doi:10.1080/08912963.2023.2286272. ISSN 0891-2963.

- ^ Ferretti, Marco P. (December 2010). "Anatomy of Haplomastodon chimborazi (Mammalia, Proboscidea) from the late Pleistocene of Ecuador and its bearing on the phylogeny and systematics of South American gomphotheres". Geodiversitas. 32 (4): 663–721. doi:10.5252/g2010n4a3. ISSN 1280-9659.

- ^ Larramendi, A. (2015). "Shoulder height, body mass and shape of proboscideans". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 60. doi:10.4202/app.00136.2014.

- ^ Bader, Camille; Delapré, Arnaud; Göhlich, Ursula B.; Houssaye, Alexandra (November 2024). "Diversity of limb long bone morphology among proboscideans: how to be the biggest one in the family". Papers in Palaeontology. 10 (6). Bibcode:2024PPal...10E1597B. doi:10.1002/spp2.1597. ISSN 2056-2799.

- ^ a b c Shoshani, J.; Tassy, P. (2005). "Advances in proboscidean taxonomy & classification, anatomy & physiology, and ecology & behavior". Quaternary International. 126–128: 5–20. Bibcode:2005QuInt.126....5S. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2004.04.011.

- ^ Wang, Shi-Qi; Deng, Tao; Ye, Jie; He, Wen; Chen, Shan-Qin (2016). "Morphological and ecological diversity of Amebelodontidae (Proboscidea, Mammalia) revealed by a Miocene fossil accumulation of an upper-tuskless proboscidean". Systematic Palaeontology. 15 (8) (Online ed.): 601–615. doi:10.1080/14772019.2016.1208687. S2CID 89063787.

- ^ Mothé, Dimila; Ferretti, Marco P.; Avilla, Leonardo S. (12 January 2016). "The dance of tusks: Rediscovery of lower incisors in the pan-American proboscidean Cuvieronius hyodon revises incisor evolution in elephantimorpha". PLOS ONE. 11 (1): e0147009. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1147009M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0147009. PMC 4710528. PMID 26756209.

- ^ Lambert, W. David (2023-10-02). "Implications of discoveries of the shovel-tusked gomphothere Konobelodon (Proboscidea, Gomphotheriidae) in Eurasia for the status of Amebelodon with a new genus of shovel-tusked gomphothere, Stenobelodon". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 43. doi:10.1080/02724634.2023.2252021. ISSN 0272-4634.

- ^ Wu, Yan; Deng, Tao; Hu, Yaowu; Ma, Jiao; Zhou, Xinying; Mao, Limi; Zhang, Hanwen; Ye, Jie; Wang, Shi-Qi (2018-05-16). "A grazing Gomphotherium in Middle Miocene Central Asia, 10 million years prior to the origin of the Elephantidae". Scientific Reports. 8 (1): 7640. Bibcode:2018NatSR...8.7640W. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-25909-4. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 5956065. PMID 29769581.

- ^ Baleka, Sina; Varela, Luciano; Tambusso, P. Sebastián; Paijmans, Johanna L.A.; Mothé, Dimila; Stafford, Thomas W.; Fariña, Richard A.; Hofreiter, Michael (January 2022). "Revisiting proboscidean phylogeny and evolution through total evidence and palaeogenetic analyses including Notiomastodon ancient DNA". iScience. 25 (1): 103559. Bibcode:2022iSci...25j3559B. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2021.103559. PMC 8693454. PMID 34988402.

- ^ a b Smith, Gregory James; DeSantis, Larisa R. G. (February 2020). "Extinction of North American Cuvieronius (Mammalia: Proboscidea: Gomphotheriidae) driven by dietary resource competition with sympatric mammoths and mastodons". Paleobiology. 46 (1): 41–57. Bibcode:2020Pbio...46...41S. doi:10.1017/pab.2020.7. ISSN 0094-8373.

- ^ El Adli, Joseph J.; Fisher, Daniel C.; Cherney, Michael D.; Labarca, Rafael; Lacombat, Frédéric (July 2017). "First analysis of life history and season of death of a South American gomphothere". Quaternary International. 443: 180–188. Bibcode:2017QuInt.443..180E. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2017.03.016.

- ^ Mothé, Dimila; Avilla, Leonardo S.; Winck, Gisele R. (December 2010). "Population structure of the gomphothere Stegomastodon waringi (Mammalia: Proboscidea: Gomphotheriidae) from the Pleistocene of Brazil". Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências. 82 (4): 983–996. doi:10.1590/S0001-37652010005000001. ISSN 0001-3765. PMID 21152772.

- ^ Sanders, William J. (2023-07-07). Evolution and Fossil Record of African Proboscidea (1 ed.). Boca Raton: CRC Press. p. 94. doi:10.1201/b20016. ISBN 978-1-315-11891-8.

- ^ a b Cantalapiedra, Juan L.; Sanisdro, Oscar L.; Zhang, Hanwen; Alberdi, Mª Teresa; Prado, Jose Luis; Blanco, Fernando; Saarinen, Juha (1 July 2021). "The rise and fall of proboscidean ecological diversity". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 355 (9): 1266–1272. Bibcode:2021NatEE...5.1266C. doi:10.1038/s41559-021-01498-w. PMID 34211141. S2CID 235712060. Retrieved 21 August 2021 – via Escience.magazine.org.

- ^ Wang, Shi-Qi; Li, Yu; Duangkrayom, Jaroon; Yang, Xiang-Wen; He, Wen; Chen, Shan-Qin (2017-05-04). "A new species of Gomphotherium (Proboscidea, Mammalia) from China and the evolution of Gomphotherium in Eurasia". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 37 (3): e1318284. Bibcode:2017JVPal..37E8284W. doi:10.1080/02724634.2017.1318284. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 90593535.

- ^ Spencer LG 2022. The last North American gomphotheres. N Mex Mus Nat Hist Sci. 88:45–58.

- ^ Wang, Shi-Qi; Saegusa, Haruo; Duangkrayom, Jaroon; He, Wen; Chen, Shan-Qin (December 2017). "A new species of Tetralophodon from the Linxia Basin and the biostratigraphic significance of tetralophodont gomphotheres from the Upper Miocene of northern China". Palaeoworld. 26 (4): 703–717. doi:10.1016/j.palwor.2017.03.005.

- ^ a b Parray, Khursheed A.; Jukar, Advait M.; Paul, Abdul Qayoom; Ahmad, Ishfaq; Patnaik, Rajeev (March 2022). Silcox, Mary (ed.). "A gomphothere (Mammalia, Proboscidea) from the Quaternary of the Kashmir Valley, India". Papers in Palaeontology. 8 (2). Bibcode:2022PPal....8E1427P. doi:10.1002/spp2.1427. ISSN 2056-2799. S2CID 247653516.

- ^ Konidaris, George E.; Tsoukala, Evangelia (2022), Vlachos, Evangelos (ed.), "The Fossil Record of the Neogene Proboscidea (Mammalia) in Greece", Fossil Vertebrates of Greece Vol. 1, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 299–344, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-68398-6_12, ISBN 978-3-030-68397-9, retrieved 2023-03-25

- ^ Sanders, William J.; Haile-Selassie, Yohannes (June 2012). "A New Assemblage of Mid-Pliocene Proboscideans from the Woranso-Mille Area, Afar Region, Ethiopia: Taxonomic, Evolutionary, and Paleoecological Considerations". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 19 (2): 105–128. doi:10.1007/s10914-011-9181-y. ISSN 1064-7554. S2CID 254703858.

- ^ a b Mothé, Dimila; dos Santos Avilla, Leonardo; Asevedo, Lidiane; Borges-Silva, Leon; Rosas, Mariane; Labarca-Encina, Rafael; Souberlich, Ricardo; Soibelzon, Esteban; Roman-Carrion, José Luis; Ríos, Sergio D.; Rincon, Ascanio D.; Cardoso de Oliveira, Gina; Pereira Lopes, Renato (30 September 2016). "Sixty years after 'The mastodonts of Brazil': The state of the art of South American proboscideans (Proboscidea, Gomphotheriidae)" (PDF). Quaternary International. 443: 52–64. Bibcode:2017QuInt.443...52M. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2016.08.028.

- ^ Konidaris, George E.; Tsoukala, Evangelia (2022), Vlachos, Evangelos (ed.), "The Fossil Record of the Neogene Proboscidea (Mammalia) in Greece", Fossil Vertebrates of Greece Vol. 1, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 299–344, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-68398-6_12, ISBN 978-3-030-68397-9, S2CID 245023119, retrieved 2023-03-23

- ^ Konidaris, George E.; Roussiakis, Socrates J. (2018-11-02). "The first record of Anancus (Mammalia, Proboscidea) in the late Miocene of Greece and reappraisal of the primitive anancines from Europe". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 38 (6): e1534118. Bibcode:2018JVPal..38E4118K. doi:10.1080/02724634.2018.1534118. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 91391249.

- ^ Rivals, Florent; Mol, Dick; Lacombat, Frédéric; Lister, Adrian M.; Semprebon, Gina M. (August 2015). "Resource partitioning and niche separation between mammoths (Mammuthus rumanus and Mammuthus meridionalis) and gomphotheres (Anancus arvernensis) in the Early Pleistocene of Europe". Quaternary International. 379: 164–170. Bibcode:2015QuInt.379..164R. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2014.12.031.

- ^ Wang, Yuan; Jin, Chang-zhu; Mead, Jim I. (August 2014). "New remains of Sinomastodon yangziensis (Proboscidea, Gomphotheriidae) from Sanhe karst Cave, with discussion on the evolution of Pleistocene Sinomastodon in South China". Quaternary International. 339–340: 90–96. Bibcode:2014QuInt.339...90W. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2013.03.006.

- ^ a b Lister, Adrian M. (August 2013). "The role of behaviour in adaptive morphological evolution of African proboscideans". Nature. 500 (7462): 331–334. Bibcode:2013Natur.500..331L. doi:10.1038/nature12275. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 23803767. S2CID 883007.

External links

[edit]- "Buried Treasure in the Sierra Nevada Foothills". Sierra College. Archived from the original on 2019-07-27. Retrieved 2014-05-21. (article about a fossil exhibit at the Sierra College Natural History Museum)

- "Gomphothere description including images". Sierra College. Archived from the original on 2019-07-27. Retrieved 2014-05-21.

- ""King Tusk" Gomphothere Excavation". Sierra College. Archived from the original on 2019-07-27. Retrieved 2014-05-21. (photos from the excavation of a Gomphothere skeleton on the Sierra College website)

- "The Gomphotheriidae". University of California Museum of Paleontology.