Ghana Armed Forces

The Ghana Armed Forces (GAF) is the state military organisation of Ghana, consisting of the Army (GA), Navy (GN), and Ghana Air Force.[3]

The Commander-in-Chief of the Ghana Armed Forces is the president of Ghana, who is also the supreme military commander of the Border Guard Unit (BGU). The armed forces are managed by the Minister of Defence[4] and the Chief of Defence Staff.

History

[edit]In 1879, the Gold Coast Constabulary was established by personnel of the Hausa Constabulary of Southern Nigeria, to perform internal security and police duties in the British colony of the Gold Coast. In this guise, the regiment earned its first battle honour as part of the Ashanti campaign.[5]

The Gold Coast Constabulary was renamed in 1901 as the Gold Coast Regiment, following the foundation of the West African Frontier Force, under the direction of the Colonial Office of the British Government. The regiment raised a total of five battalions for service during the First World War, all of which served during the East Africa campaign. During the Second World War, the regiment raised nine battalions, and saw action in Kenya's Northern Frontier District, Italian Somaliland, Abyssinia and Burma as part of the 2nd (West Africa) Infantry Brigade.[6] Gold Coast soldiers returning from the Far East carried different perspectives from when they had departed.

Internal operations

[edit]The Ghana Armed Forces were formed in 1957. Major General Stephen Otu was appointed Chief of Defence Staff in September 1961. From 1966, the Armed Forces were extensively involved in politics, mounting several coups. Kwame Nkrumah had become Ghana's first prime minister when the country became independent in 1957. As Nkrumah's rule wore on, he began to take actions which disquieted the leadership of the armed forces, including the creation and expansion of the President's Own Guard Regiment (POGR).[7][8]

As a result, on February 24, 1966, a small number of Army personnel and senior police officials, led by Colonel Emmanuel Kotoka, commander of the Second Brigade at Kumasi, Major Akwasi Afrifa, (staff officer in charge of army training and operations), Lieutenant General (retired) Joseph Ankrah, and J.W.K. Harlley, (the police inspector general), successfully launched "Operation Cold Chop", the 1966 Ghanaian coup d'état, against the Nkrumah regime.[7] The group formed the National Liberation Council, which ruled Ghana from 1966 to 1969.

The Armed Forces seized power again in January 1972, after the reinstated civilian government cut military privileges and started changing the leadership of the army's combat units. Lieutenant Colonel Ignatius Kutu Acheampong (temporary commander of the First Brigade around Accra) led the bloodless 1972 Ghanaian coup d'état that ended the Second Republic.[9] Thus the National Redemption Council was formed. Acheampong became head of state, and the NRC ruled from 1972 to 1975.

On October 9, 1975, the NRC was replaced by the Supreme Military Council (SMC).[10] Council members were Colonel Acheampong, (chairman, who was also promoted straight from Colonel to General), Lt. Gen. Fred Akuffo, (the Chief of Defence Staff), and the army, navy, air force and Border Guard Unit commanders.

In July 1978, in a sudden move, the other SMC officers forced Acheampong to resign, replacing him with Lt. Gen. Akuffo. The SMC apparently acted in response to continuing pressure to find a solution to the country's economic dilemma; inflation was estimated to be as high as 300% that year. The council was also motivated by Acheampong's failure to dampen rising political pressure for changes. Akuffo, the new SMC chairman, promised publicly to hand over political power to a new government to be elected by July 1, 1979.[11]

The decree lifting the ban on party politics went into effect on January 1, 1979, as planned. However, in June, just before the scheduled resumption of civilian rule, a group of young armed forces officers, led by Flight Lieutenant Jerry Rawlings, mounted the 1979 Ghanaian coup d'état. They put in place the Armed Forces Revolutionary Council, which governed until September 1979. However, in 1981, Rawlings deposed the new civilian government again, in the 1981 Ghanaian coup d'état.[12] This time Rawlings established the Provisional National Defence Council (PNDC). The PNDC remained in government until January 7, 1993. In the last years of the PNDC, Jerry Rawlings assumed civilian status; he was elected as a civilian President in 1993 and continued as president until 2001.

-

A female sergeant from the Ghana Army on a military exercise.

-

Ghana Army soldiers during a simulated amphibious landing in Southwest Ghana.

-

Posed photograph from a U.S. Marine Corps -Ghana jungle warfare training exercise.

-

Honour guards from Ghana Air Force during a welcoming ceremony for Ivory Coast Gen. Soumaila Bakayoko, the ECOWAS chair of chiefs of defence staff, during Exercise Western Accord 13.

External operations

[edit]

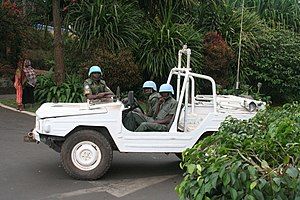

The Armed Forces' first external operation was the United Nations Operation in the Congo in the early 1960s.[13] The GAF operated in the Balkans, including with UNMIK.[14] Ghanaian operations within Africa included the UNAMIR deployment which became entangled in the Rwandan genocide. In his book Shake Hands with the Devil, Canadian Forces commander Romeo Dallaire gave the Ghanaian soldiers high praise for their work during that deployment. During the Liberian Civil War, Ghanaian activities helped pave the way for the Accra Comprehensive Peace Agreement, among others.[15] Additional operations in Asia have included Iran and Iraq in the Iran–Iraq War,[16] Kuwait and Lebanon civil war among others.[17][18]

A total of 3,359 Ghana Army soldiers and 283 Ghana Military Police operated as part of UNTAC in Cambodia.[19] The UNTAC operation lasted two years, 1992−1993.[19] After the long running Cambodia civil war ignited by external interventions, a resolution was accepted by the four warring factional parties.[19] Operation UNTAC was the largest Ghanaian external operation since Ghana's first external military operation, ONUC in the Congo in the 1960s.[19] Operation UNTAC and its contingent UNAMIC had a combined budget of more than $1.6 billion.[19]

In 2012, closer military cooperation was agreed with the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation. In 2013, the Armed Forces agreed closer military cooperation with the China People's Liberation Army,[20] and with the Armed Forces of the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Ghana Army

[edit]The Ghana Army is structured as follows:

- The Northern Command with headquarters in Tamale, Central Command with headquarters in Kumasi and the Southern Command with headquarters in Accra. In March 2000 Northern and Southern Commands were formed after the two infantry brigades were upgraded in status.[21] Previously there were three brigades: 1st Infantry Brigade (HQ in Teshie), 2nd Infantry Brigade (HQ in Kumasi) and Support Services Brigade (HQ in Burma Camp).

- 6 Infantry Battalions of the Ghana Regiment. 3rd Battalion of Infantry, 4th Battalion of Infantry and 6th Battalion of Infantry in the Northern Command, 1st Battalion of Infantry, 2nd Battalion of Infantry and 5th Battalion of Infantry in the Southern Command.

- two Airborne companies attached to Northern Command; Airborne Force

- 64 Infantry Regiment, a presidential guard force (formerly known as President's Own Guard Regiment)

- 1 Training Battalion

- One Staff College

- Reconnaissance Armoured Regiment (two armoured reconnaissance squadrons)

- Defence Signal Regiment (Ghana)

- Two Engineer Regiments (48 Engineer Regiment and 49 Engineer Regiment)

- 66 Artillery Regiment

In 1996, the Support Services Brigade was reorganized and transferred from the Army to be responsible to the Armed Forces GHQ. From that point its units included 49 Engineer Regiment, the Ghana Military Police, Defence Signal Regiment (Ghana), FRO, Forces Pay Office, 37 Military Hospital, Defence Mechanical Transport Battalion (Def MT Bn), Base Ordnance Depot, Base Ammunition Depot, Base Supply Depot, Base Workshop, Armed Forces Printing Press (AFPP), Armed Forces Fire Service (AFFS), the Ghana Armed Forces Central Band, Ghana Armed Forces Institution (GAFI), 1 Forces Movement Unit (Tema Port), 5 Forces Movement Unit, Base Engineer Technical Services (BETS), 5 Garrison Education Centre (5 GEC), the Armed Forces Museum, Army Signals Training School, and the Armed Forces Secondary Technical School (AFSTS). By 2016 the Forces Pay Office had been upgraded to the Forces Pay Regiment.

The Armed Forces uses imported weaponry and locally manufactured secondary equipment. M16 rifles, AK-47s, Type 56 assault rifles, ballistic vests and personal armor are standard issue, while much of the secondary equipment used by the Army and Air Force are manufactured internally by the Defence Industries Holding Company (DIHOC). External suppliers include Russia, Iran, and China.[22]

Peacekeeping Operations

[edit]

The Armed Forces are heavily committed to international peacekeeping operations. Ghana prefers to send its troops to operations in Africa. However the United Nations has used Ghanaian forces in countries as diverse as Afghanistan, Iraq, Kosovo, Georgia, Nepal, Cambodia and Lebanon.[23] Currently, Ghanaian armed forces are posted to United Nations peacekeeping missions in:[24]

- MONUC (Democratic Republic of Congo) − 464

- UNMIL (Liberia) − 852 (disestablished 2018)

- UNAMSIL (Sierra Leone) − 782

- UNIFIL (Lebanon) − 651

Ghana armed forces provided the first Force Commander of the Economic Community of West African States Monitoring Group (ECOMOG), Lieutenant General Arnold Quainoo. Quainoo led the force from July 1990 to September 1990.[25]

Ghana Armed Forces peacekeepers have many roles: patrolling, as military police, electoral observers, de-miners (bomb disposal units and clearance divers), ceasefire monitors, humanitarian aid workers, and even special forces or frogmen against insurgents.[26]

Niger Coup

[edit]A group of opposition political parties and civil society organizations, comprising the National Democratic Congress (NDC)[27][28] and Ghana Union Movement (GUM),[29] has jointly urged the Akufo-Addo administration to refrain from deploying the Ghana Armed Forces to restore the democratically elected president of Niger, Mohamed Bazoum, who was ousted from power by General Abdourahamane Tchiani.[30]

However, Hon. Kennedy Ohene Agyapong, the Chairperson of the Interior and Defense Committee in Parliament, has expressed his endorsement of the nation's deployment of troops to Niger.[31]

Ghana Air Force

[edit]The Ghana Air Force is headquartered in Burma Camp in Accra, and operates from bases in Accra (main transport base), Tamale (combat and training base)and Sekondi-Takoradi (training base). The GHF military doctrine and stated mission is to perform counterinsurgency operations within Ghana or externally and to provide logistical support to the Ghana Army.[32]

Ghana Navy

[edit]The Ghana Navy's mission is to provide defence of Ghana and its territorial waters, fishery protection, exclusive economic zone, and internal security on Lake Volta. It is also tasked with resupplying GA (Ghana Army) peacekeepers in Africa, fighting maritime criminal activities such as Piracy, disaster and humanitarian relief operations, and evacuation of Ghanaian citizens and other nationals from troubled spots.[33] In 1994 the Navy was re-organized into an Eastern command, with headquarters at Tema, and a Western command, with headquarters at Sekondi-Takoradi.[33]

GAF Business

[edit]GAF Military private bank

[edit]

The Ghana Armed Forces, in addition to owning its own arms industry weapons and military technology and equipment manufacturer (DIHOC − Defence Industries Holding Company), operates its own private bank. The military private bank is sited at Burma Camp and serves Ghanaian military personnel and their civilian counterparts.[34]

Military hospitals

[edit]The GAF has two hospitals, the 37 Military Hospital in Accra and the Kumasi Military Hospital in the north.[35] The 37 Military Hospital has recently undergone expansion and its facilities include a twenty-four-hour Emergency Department (ED).[36]

The GAF main military hospital has been organized into departments and divisions, which created structure within the establishment.[36] The Divisions and Departments (the units) are developed and joined according to medical, paramedical and administrative lines and each of these units has its own departmental head.[36] The GAF military hospital is staffed by GAF military personnel and also houses a medical education training facility.[36] 37 Military Hospital is also accredited for post-graduate medical education teaching.[36] Vyacheslav Lebedev, Chairman of the Supreme Court of Russia, expressed gratitude following his emergency treatment at the hospital.[37]

Cadets and schools

[edit]The Ghana Army operates a Cadet Corps for GAF Cadets whom go on to Military Education and Training and Recruit Training graduation from the GAF Military Academy for Army Recruit and Seaman Recruit prior to enlistment into the Army, Navy or Air Force.

Training institutions include the Ghana Military Academy and the Ghana Army-sponsored Cadet Corps. Also located in Accra is the internationally funded Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre, which is not part of the Armed Forces but provides a wide-ranging of peace operations training, including to GAF personnel.

Ghana Armed Forces Command and Staff College

[edit]The Ghana Armed Forces Command and Staff College (GAFCSC) dates back to 1963. It was to provide training for Ghana Armed Forces (GAF) officers and affiliated officers from Africa, focusing on command and staff duties. Throughout its history, it has hosted and educated individuals from neighboring African states. It focuses on military and defense courses, culminating in the issuance of the Pass Staff College (PSC) certificate.[38]

The range of programs expanded, driven by the demands of the global environment. The Ghana Armed Forces have been engaged in peacekeeping operations since 1960. This meant broadening the array of courses provided by GAFCSC. Consequently, the college aimed to establish partnerships with the University of Ghana and GIMPA to offer diverse peacekeeping and other courses. With the attainment of Institutional Accreditation, the college is now prepared to conduct its own courses, while still maintaining its collaborative association with the University of Ghana and GIMPA.[38]

Defence budget

[edit]| Ghana Military–industrial complex and Defence industry budgetary history | |

|

|

| Ghana Armed Forces Defence budget percentage growth rate | Ghana Armed Forces Defence budget percentage |

Salary Structure

[edit]The Single Spine Salary Structure (SSSS) is the payment made to the Ghana Arm Forces. The salary structure started in 2010 has increased the income of the military. Payment structure with the Single Spine differs from each officer depending on their ranking.[39][40]

Military clothing and prohibition of photography

[edit]Ghanaian statutory law officially prohibits civilians and foreign nationals from wearing military apparel such as camouflage clothing, or clothing which resembles military dress. Officially, fines and/or short prison sentences can be passed against civilians seen in military dress in public.[41] In addition, Ghanaian law prohibits the photographing of Ghana Armed Forces (GAF) Ghana Military Police (GMP) police or GAF military personnel and vehicles while on duty, strategic sites such as Kotoka International Airport when in use, and the seat of the Ghanaian government, Jubilee House.[41]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "General recruitment exercise-2013 Entry requirements into the Ghana Armed Forces". gaf.mil.gh. 2013. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 25 April 2014.

- ^ a b c CIA World Factbook, accessed 29 October 2020

- ^ Central Intelligence Agency, The World Factbook: Ghana, accessed 15 November 2011

- ^ International Institute for Strategic Studies; Hackett, James (ed.) (3 February 2010). The Military Balance 2010. London: Routledge. pp. 309–311. ISBN 978-1857435573.

{{cite book}}:|author2=has generic name (help) - ^ "7 Best Hausa in Gold Coast ideas | british colonies, police duty, gold coast". Pinterest. Retrieved 2021-01-18.

- ^ "Combat Supprt [sic] Arms". Gaf.mil.gh. Ghana Armed Forces. Archived from the original on 2011-09-28. Retrieved 2014-04-26.

- ^ a b La Verle Berry (ed.), 'The National Liberation Council,' in Ghana Country Study, Library of Congress, research completed November 1994

- ^ "History of Gafcsc | Ghana Armed Forces Command and Staff College". Archived from the original on 2023-08-16. Retrieved 2023-08-16.

- ^ Berry (ed.), 1994

- ^ "Ghana". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. Retrieved 2007-03-20.

- ^ McLaughlin & Owusu-Ansah (1994), "The National Redemption Council Years, 1972-79".

- ^ Hutchful, Eboe. "Institutional Decomposition and Junior Ranks’ Political Action in Ghana." in Hutchful and Bathilly, The military and militarism in Africa, CODESRIA, (1998): 211-56.

- ^ "ONUC−Congo". Gaf.mil.gh. Ghana Armed Forces. Archived from the original on 2016-11-24. Retrieved 2014-04-27.

- ^ Aning, Kwesi; Aubyn, Festus K. (2013-02-28). "Ghana". Providing Peacekeepers. pp. 269–290. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199672820.003.0013. ISBN 978-0-19-967282-0.

- ^ "ECOMOG−Liberia". Gaf.mil.gh. Ghana Armed Forces. Archived from the original on 2014-03-06. Retrieved 2014-04-27.

- ^ "Iran–Iraq War". un.org. Retrieved 2014-04-27.

- ^ "UNIFIL−Lebanon". Gaf.mil.gh. Ghana Armed Forces. Retrieved 2014-04-27.

- ^ "Lebanese Govt to erect monument in honour of Ghanaian peacekeepers". Gaf.mil.gh. Ghana Armed Forces. 2 June 2011. Retrieved 2014-04-27.

- ^ a b c d e "UNTAC−Cambodia". Gaf.mil.gh. Ghana Armed Forces. Archived from the original on 2016-11-24. Retrieved 2014-04-25.

- ^ "China-Ghana strengthen military ties". People Daily Online. Retrieved 23 June 2013.

- ^ Africa South of the Sahara 2003, 32nd Edition

- ^ "Two-thirds of African countries 'now using Chinese weapons'". The Independent. 2016-03-01. Retrieved 2022-03-05.

- ^ "Ghana's Regional Security Policy: Costs, Benefits and Consistency". Kaiptc.org. Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre. p. 33. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-05-08. Retrieved 2014-04-27.

- ^ "Ghana Armed Forces − Peace operations". RULAC. Rule of Law in Armed Conflicts Project. Retrieved 2014-04-27.

- ^ Berman, Eric G.; Sams, Katie E. (2000). Peacekeeping In Africa : Capabilities And Culpabilities. Geneva: United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research. pp. 94–95. ISBN 92-9045-133-5.

- ^ "International Peacekeeping". Gaf.mil.gh. Ghana Armed Forces. Archived from the original on 2013-07-04. Retrieved 2014-04-25.

- ^ "NDC kicks against planned military intervention in troubled Niger". Citinewsroom - Comprehensive News in Ghana. 2023-08-10. Retrieved 2023-08-16.

- ^ "Niger Coup: War cannot be a preferred option – NDC to ECOWAS". www.myjoyonline.com. 10 August 2023. Retrieved 2023-08-16.

- ^ "Osofo Kyiri Abosom threatens to demonstrate if Akufo-Addo sends troops to Niger". Citinewsroom - Comprehensive News in Ghana. 2023-08-14. Retrieved 2023-08-16.

- ^ "Don't send troops to Niger – Presby Church". www.myjoyonline.com. 16 August 2023. Retrieved 2023-08-16.

- ^ "I support sending Ghanaian troops to Niger - Chair of Defence and Interior Committee of Parliament". GhanaWeb. 2023-08-16. Retrieved 2023-08-16.

- ^ Ghana air force[permanent dead link]. gaf.mil.gh.

- ^ a b "Historical Background of The Ghana Navy". Official website. Ghana Armed Forces. Archived from the original on 2007-08-27. Retrieved 2007-06-11.

- ^ "GAF justifies decision to operate a bank". Modernghana.com. 2013-02-02. Retrieved 2014-04-30.

- ^ Hospital, Military. "Work On Kumasi Military Hospital Progresses". ghana.gov.gh. Government of Ghana. Archived from the original on 20 April 2018. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ a b c d e "37 Military Hospital − Hospital description". Electives.net. Archived from the original on 2014-03-01. Retrieved 2014-04-30.

- ^ "Russian CJ Returns Home − Russian CJ Grateful to Ghanaians". Gaf.mil.gh. Ghana Armed Forces. September 2013. Archived from the original on 2014-05-08. Retrieved 2014-04-30.

- ^ a b "History of Gafcsc | Ghana Armed Forces Command and Staff College". Archived from the original on 2023-08-16. Retrieved 2023-08-17.

- ^ richie (2020-03-19). "Ghana Armed Forces Salary 2021/2022". Quoterich.com. Archived from the original on 2021-02-04. Retrieved 2021-01-18.

- ^ GHStudents (2018-03-15). "Ghana Army Salary Structure & Rank". GH Students. Retrieved 2021-01-18.

- ^ a b Ghana armed forces Archived 2011-07-21 at the Wayback Machine. gaf.mil.gh.

Further reading

[edit]- General History of the Ghana Armed Forces – a Reference Volume, (Professor) Stephen Addae, Ministry of Defence of Ghana Armed Forces, Accra, 2005, ISBN 9988-8335-0-4. Nearly 700 pages but quite readable. Very poor bibliography.

External links

[edit]- Ghana Armed Forces, Ghana armed forces official website Archived 2011-07-21 at the Wayback Machine

- How to join the Ghana Armed Forces . [1] Archived 2014-08-21 at the Wayback Machine