Calgary

Calgary | |

|---|---|

| City of Calgary | |

|

| |

| Nicknames: | |

| Motto: Onward | |

Interactive map of Calgary | |

| Coordinates: 51°3′N 114°4′W / 51.050°N 114.067°W | |

| Country | Canada |

| Province | Alberta |

| Region | Calgary Metropolitan Region |

| Census division | 6 |

| Municipal districts | Rocky View County and Foothills County |

| Founded | 1875 |

| Incorporated[3] | |

| • Town | November 7, 1884 |

| • City | January 1, 1894 |

| Named for | Calgary, Mull |

| Government | |

| • Body | Calgary City Council |

| • Mayor | Jyoti Gondek |

| • Manager | David Duckworth[4] |

| Area (2021)[5] | |

| • Land | 820.62 km2 (316.84 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 621.72 km2 (240.05 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 5,098.68 km2 (1,968.61 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 1,045 m (3,428 ft) |

| Population | |

• City | 1,306,784 (3rd) |

| • Density | 1,592.4/km2 (4,124/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 1,305,550 (4th) |

| • Urban density | 2,099.9/km2 (5,439/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 1,481,806 (5th) |

| • Metro density | 290.6/km2 (753/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Calgarian |

| Time zone | UTC−07:00 (MST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−06:00 (MDT) |

| FSAs | |

| Area code(s) | 403, 587, 825, 368 |

| NTS Map | 082O01 |

| GNBC Code | IAKID |

| GDP (Calgary CMA) | CA$102.66 billion (2020)[9] |

| GDP per capita (Calgary CMA) | CA$79,885 (2022)[10] |

| Website | www |

Calgary is the largest city in the Canadian province of Alberta. It is the largest metro area within the three prairie provinces. As of 2021, the city proper had a population of 1,306,784 and a metropolitan population of 1,680,000 making it the third-largest city and fifth-largest metropolitan area in Canada.[11]

Calgary is at the confluence of the Bow River and the Elbow River in the southwest of the province, in the transitional area between the Rocky Mountain Foothills and the Canadian Prairies, about 80 km (50 mi) east of the front ranges of the Canadian Rockies, roughly 299 km (186 mi) south of the provincial capital of Edmonton and approximately 240 km (150 mi) north of the Canada–United States border. The city anchors the south end of the Statistics Canada-defined urban area, the Calgary–Edmonton Corridor.[12]

Calgary's economy includes activity in many sectors: energy; financial services; film and television; transportation and logistics; technology; manufacturing; aerospace; health and wellness; retail; and tourism.[13] The Calgary Metropolitan Region is home to Canada's second-largest number of corporate head offices among the country's 800 largest corporations.[14] In 2015, Calgary had the largest number of millionaires per capita of any major Canadian city.[15] In 2022, Calgary was ranked alongside Zürich as the third most livable city in the world, ranking first in Canada and in North America.[16] In 1988, it became the first Canadian city to host the Olympic Winter Games.[17]

Etymology

[edit]Calgary was named after Calgary Castle (in Scottish Gaelic, Caisteal Chalgairidh) on the Isle of Mull in Scotland.[18] Colonel James Macleod, the Commissioner of the North-West Mounted Police, had been a frequent summer guest there. In 1876, shortly after returning to Canada, he suggested its name for what became Fort Calgary.

The Indigenous peoples of Southern Alberta refer to the Calgary area as "elbow", in reference to the sharp bend made by the Bow River and the Elbow River. In some cases, the area was named after the reeds that grew along the riverbanks, reeds that had been used to fashion bows. In the Blackfoot language (Siksiká) the area is known as Mohkínstsis akápiyoyis, meaning "elbow many houses", reflecting its strong settler presence. The shorter form of the Blackfoot name, Mohkínstsis, simply meaning "elbow",[19][20][21] is the popular Indigenous term for the Calgary area.[22][23][24][25][26] In the Nakoda or Stoney language, the area is known as Wîchîspa Oyade or Wenchi Ispase, both meaning "elbow".[19][21] In the Cree language, the area is known as otôskwanihk (ᐅᑑᐢᑿᓂᕽ) meaning "at the elbow"[27] or otôskwunee meaning "elbow". In the Tsuutʼina language (Sarcee), the area is known as Guts’ists’i (older orthography, Kootsisáw) meaning "elbow".[19][21] In Kutenai language, the city is referred to as ʔaknuqtapȼik’.[28] In the Slavey language, the area is known as Klincho-tinay-indihay meaning "many horse town", referring to the Calgary Stampede[19] and the city's settler heritage.[21]

There have been several attempts to revive the Indigenous names of Calgary. In response to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, local post-secondary institutions adopted "official acknowledgements" of Indigenous territory using the Blackfoot name of the city, Mohkínstsis.[24][25][29][30][31] In 2017, the Stoney Nakoda sent an application to the Government of Alberta, to rename Calgary as Wichispa Oyade meaning "elbow town";[32] however, this was challenged by the Piikani Blackfoot.[33]

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]The Calgary area was inhabited by pre-Clovis people whose presence traces back at least 11,000 years.[34] The area has been inhabited by multiple First Nations, the Niitsitapi (Blackfoot Confederacy; Siksika, Kainai, Piikani), îyârhe Nakoda, Tsuutʼina peoples and Métis Nation, Region 3.

In 1787, David Thompson, a 17-year-old cartographer with the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC), spent the winter with a band of Piikani Nation encamped along the Bow River. He was also a fur trader and surveyor and the first recorded European to visit the area. John Glenn was the first documented European settler in the Calgary area, in 1873.[35] In spring 1875, three priests – Lacombe, Remus, and Scollen – built a small log cabin on the banks of the Elbow River.[36]

In the fall of 1875, the site became a post of the North-West Mounted Police (NWMP) (now the Royal Canadian Mounted Police or RCMP). The NWMP detachment was assigned to protect the western plains from US whisky traders, and to protect the fur trade, and Inspector Éphrem-A. Brisebois led fifty Mounties as part of F Troop north from Fort Macleod to establish the site.[36] The I. G. Baker Company of Fort Benton, Montana, was contracted to construct a suitable fort, and after its completion, the Baker company built a log store next to the fort.[37] The NWMP fort remained officially nameless until construction was complete, although it had been referred to as "The Mouth" by people at Fort Macleod.[38] At Christmas dinner NWMP Inspector Éphrem-A. Brisebois christened the unnamed Fort "Fort Brisebois", a decision which caught the ire of his superiors Colonel James Macleod and Major Acheson Irvine.[38] Major Irvine cancelled the order by Brisebois and wrote Hewitt Bernard, the then Deputy Minister of Justice in Ottawa, describing the situation and suggesting the name "Calgary" put forward by Colonel Macleod. Edward Blake, at the time Minister of Justice, agreed with the name and in the spring of 1876, Fort Calgary was officially established.[39]

In 1877, the First Nations ceded title to the Fort Calgary region through Treaty 7.[citation needed]

In 1881 the federal government began to offer leases for cattle ranching in Alberta (up to 400 km2 (100,000 acres) for one cent per acre per year) under the Dominion Lands Act, which became a catalyst for immigration to the settlement. The I. G. Baker Company drove the first herd of cattle to the region in the same year for the Cochrane area by order of Major James Walker.[40]

The Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) reached the area in August 1883 and constructed a railway station on the CPR-owned Section 15, neighbouring the townsite across the Elbow River to the east on Section 14. The difficulty in crossing the river and the CPR's efforts to persuade residents resulted in the core of the Calgary townsite moving onto Section 15, with the fate of the old townsite sealed when the post office was anonymously moved across the icy Elbow River during the night.[41] The CPR subdivided Section 15 and began selling lots surrounding the station, $450 for corner lots and $350 for all others; and pioneer Felix McHugh constructed the first private building on the site.[41] Earlier in the decade it was not expected that the railway would pass near Calgary; instead, the preferred route put forward by people concerned with the young nation's defence was passing near Edmonton and through the Yellowhead Pass. However, in 1881 CPR changed the plans preferring the direct route through the prairies by way of Kicking Horse Pass.[42] Along with the CPR, August 1883 brought Calgary the first edition of the Calgary Herald published on the 31st under the title The Calgary Herald, Mining and Ranche Advocate and General Advertiser by teacher Andrew M. Armour and printer Thomas B. Braden, a weekly newspaper with a subscription price of $1 per year.[43]

Over a century later, the CPR headquarters moved to Calgary from Montreal in 1996.[44]

Residents of the now-eight-year-old settlement sought to form a local government of their own. In the first weeks of 1884, James Reilly who was building the Royal Hotel east of the Elbow River circulated 200 handbills announcing a public meeting on January 7, 1884, at the Methodist Church.[45][46] At the full meeting Reilly advocated for a bridge across the Elbow River and a civic committee to watch over the interests of the public until Calgary could be incorporated. The attendees were enthusiastic about the committee and on the next evening a vote was held to elect the seven members. A total of 24 candidates were nominated, which equalled 10 per cent of Calgary's male population. Major James Walker received 88 votes, the most amongst the candidates, the other six members were Dr. Andrew Henderson, George Clift King, Thomas Swan, George Murdoch, J. D. Moulton, and Captain John Stewart.[45] The civic committee met with Edgar Dewdney, Lieutenant Governor of the North-West Territories, who happened to be in Calgary at the time,[46] to discuss an allowance for a school, an increase from $300 to $1,000 grant for a bridge over the Elbow River, incorporation as a town, and representation for Calgary in the Legislative Council of the North-West Territories.[47] The committee was successful in getting an additional $200 for the bridge,[47] In May, Major Walker, acting on instructions from the NWT Lieutenant-governor, organized a public meeting in the NWMP barracks room on the issue of getting a representative in the NWT Council. Walker wrote the clerk of the Council that he was prepared to produce evidence that Calgary and environs (an area of 1000 square miles) held 1000 residents, the requirement for having a Council member.[48] A by-election was held on June 28, 1884, where James Davidson Geddes defeated James Kidd Oswald to become the Calgary electoral district representative on the 1st Council of the North-West Territories.[49][50]

As for education, Calgary moved quickly: the Citizen's Committee raised $125 on February 6, 1884, and the first school opened for twelve children days later on February 18, led by teacher John William Costello.[51] The private school was not enough for the needs of the town and following a petition by James Walker the Calgary Protestant Public School District No. 19 was formed by the Legislature on March 2, 1885.[52]

On November 27, 1884, Lieutenant Governor Dewdney proclaimed the incorporation of The Town of Calgary.[53] Shortly after on December 3, Calgarians went to the polls to elect their first mayor and four councillors. The North-West Municipal Ordinance of 1884 provided voting rights to any male British subject over 21 years of age who owned at minimum $300 of property. Each elector was able to cast one vote for the mayor and up to four votes for the councillors (plurality block voting).[54] George Murdoch won the mayoral race in a landslide victory with 202 votes over E. Redpath's 16, while Simon Jackson Hogg, Neville James Lindsay, Joseph Henry Millward, and Simon John Clarke were elected councillors.[55] The next morning the Council met for the first time at Beaudoin and Clarke's Saloon.[56]

Law and order remained top of mind in the frontier town, in early 1884 Jack Campbell was appointed as a constable for the community, and in early 1885 the Town Council passed By-law Eleven creating the position of Chief Constable and assigning relevant duties, a precursor to the Calgary Police Service. The first chief constable, John (Jack) S. Ingram, who had previously served as the first police chief in Winnipeg, was empowered to arrest drunken and disorderly people, stop all fast riding in town, attend all fires and council meetings.[57][58] Calgary Town Council was eager to employ constables versus contracting the NWMP for town duty as the police force was seen as a money-making proposition. Constables received half of the fines from liquor cases, meaning Chief Constable Ingram could easily pay his $60 per month salary and the expense of a town jail.[58]

Turmoil in 1885 and 1886 and the "Sandstone City"

[edit]For the Town of Calgary, 1884 turned out to be a success. However, two dark years lay ahead for the fledgling community. The turmoil started in late 1885, when Councillor Clarke was arrested for threatening a plain-clothes Mountie who entered his saloon to conduct a late-night search. When the officer failed to produce a search warrant, Clarke chased him off the premises; however, the Mountie returned with reinforcements and arrested Clarke.[59] Clarke found himself before Stipendiary Magistrate Jeremiah Travis, a proponent of the temperance movement who was appalled by the open traffic of liquor, gambling and prostitution in Calgary despite prohibition in the North-West Territories.[60] Travis' view was accurate as the Royal Commission of Liquor Traffic of 1892 found liquor was sold openly, both day and night during prohibition.[58] Travis associated Clarke with the troubles he saw in Calgary and found him guilty, and sentenced Clarke to six months with hard labour.[60] Murdoch and the other members of Council were shocked, and a public meeting was held at Boynton's Hall in which a decision was made to send a delegation to Ottawa to seek an overruling of Travis' judgement by the Department of Justice. The community quickly raised $500, and Murdoch and a group of residents headed east.[60] The punishment of Clarke did not escape Hugh Cayley the editor of the Calgary Herald and Clerk of the District Court. Cayley published articles critical of Travis and his judgment, in which Travis responded by calling Cayley to court, dismissing him from his position as Clerk, ordering Cayley to apologize and pay a $100 fine.[61] Cayley refused to pay the fine, which Travis increased to $500, and on January 5, the day after the January 1886 Calgary town election, Cayley was imprisoned by Travis.[61]

Murdoch returned to Calgary on December 27, 1885, only a week before the election to find the town in disarray.[61] Shortly before the 1886 election, G. E. Marsh brought a charge of corruption against Murdoch and council over irregularities in the voters' list. Travis found Murdoch and the councillors guilty, disqualifying them from running in the 1886 election, barring them from municipal office for two years, and fining Murdoch $100, and the councillors $20. This was despite the fact Murdoch was visiting Eastern Canada while the alleged tampering was occurring.[62] Travis' disqualification did not dissuade Calgary voters, and Murdoch defeated his opponent James Reilly by a significant margin in early January to be re-elected as mayor.[63] Travis accepted a petition from Reilly to unseat Murdoch and two of the elected councillors, and declare Reilly the mayor of Calgary.[64] Both Murdoch and Reilly claimed to be the lawful mayor of the growingly disorganized Town of Calgary, both holding council meetings and attempting to govern.[64] Word of the issues in Calgary reached the Minister of Justice John Sparrow David Thompson in Ottawa who ordered Justice Thomas Wardlaw Taylor of Winnipeg to conduct an inquiry into the "Case of Jeremiah Travis". The federal government acted before receiving Taylor's report, Jeremiah Travis was suspended, and the government waited for his official tenure to expire, after which he was pensioned off.[65] Justice Taylor's report, which was released in June 1887, found Travis had exceeded his authority and erred in his judgements.[62][66]

The Territorial Council called for a new municipal election to be held in Calgary on November 3, 1886. George Clift King defeated his opponent John Lineham for the office of Mayor of Calgary.[67][68]

Calgary had only a couple days' peace following the November election before the Calgary Fire of 1886 destroyed much of the community's downtown. Part of the slow response to the fire can be attributed to the absence of functioning local government during 1886. As neither George Murdoch or James Reilly was capable of effectively governing the town, the newly ordered chemical engine for the recently organized Calgary Fire Department (Calgary Hook, Ladder and Bucket Corps) was held in the CPR's storage yard due to lack of payment. Members of the Calgary Fire Department broke into the CPR storage yard on the day of the fire to retrieve the engine.[69] In total, fourteen buildings were destroyed with losses estimated at $103,200, although no one was killed or injured.[70]

The new Town Council sprung into action, drafting a bylaw requiring all large downtown buildings to be built with sandstone, which was readily available nearby in the form of Paskapoo sandstone.[71] Following the fire several quarries were opened around the city by prominent local businessmen including Thomas Edworthy, Wesley Fletcher Orr, J. G. McCallum, and William Oliver. Prominent buildings built with sandstone following the fire include Knox Presbyterian Church (1887), Imperial Bank Building (1887), Calgary City Hall (1911), and Calgary Courthouse No. 2 (1914).[72][73]

In February 1887, Donald Watson Davis, who was running the I.G. Baker store in Calgary, was elected MP for Alberta (Provisional District). A former whisky trader in southern Alberta, he had turned his hand to building Fort Macleod and Fort Calgary. The main other contender for the job, Frank Oliver, was a prominent Edmontonian, so Davis's success was a sign that Calgary was surpassing Edmonton, previously the main centre on the western Prairies.[74]

1887 to 1900

[edit]Calgary continued to expand when real estate speculation took hold of Calgary in 1889. Speculators began buying and building west of Centre Street, and Calgary quickly began to sprawl west to the ire of property owners on the east side of town.[75] Property owners on both sides of Centre Street sought to bring development to their side of Calgary, lost successfully[clarification needed] by eastsider James Walker who convinced the Town Council to purchase land on the east side to build a stockyard, guaranteeing meat packing and processing plants would be constructed on the east side.[76] By 1892 Calgary had reached present-day Seventeenth Avenue, east to the Elbow River and west to Eighth Street,[77] and the first federal census listed the boom town at 3,876 inhabitants.[78] The economic conditions in Calgary began to deteriorate in 1892,[79] as development in the downtown slowed, the streetcar system started in 1889 was put on hold[80] and smaller property owners began to sell.[81]

The first step in connecting the District of Alberta happened in Calgary on July 21, 1890, as Minister of the Interior Edgar Dewdney turned the first sod for the Calgary and Edmonton Railway in front of two thousand residents.[82][83] The railway was completed in August 1891. Although its end-of-steel was on the south side of the river opposite Edmonton, it immensely shortened travel time between the two communities. Previously stagecoach passengers and mail could arrive in five days and animal pulled freight anywhere between two and three weeks,[84] the train was able to make the trip in only a few hours.[85]

Smallpox arrived in Calgary in June 1892 when a Chinese resident was found with the disease, and by August nine people had contracted the disease with three deaths. Calgarians placed the blame for the disease on the local Chinese population, resulting in a riot on August 2, 1892.[86] Residents descended on the Town's Chinese-owned laundries, smashing windows and attempting to burn the structures to the ground. The local police did not attempt to intervene. Mayor Alexander Lucas had inexplicably left town during the riot,[87] and when he returned home he called the NWMP in to patrol Calgary for three weeks to prevent further riots.[88][89]

Finally on January 1, 1894, Calgary was granted a charter by the 2nd North-West Legislative Assembly, officially titled Ordinance 33 of 1894, the City of Calgary Charter elevated the frontier town to the status of a full-fledged city.[90] Calgary became the first city in the North-West Territories, receiving its charter a decade before Edmonton and Regina. The Calgary charter remained in force until it was repealed with the Cities Act in 1950. The charter came into effect in such a way as to prevent the regularly scheduled municipal election in December 1893, and recognizing the importance of the moment, the entire Town Council resigned to ensure the new city could choose the first Calgary City Council.[91] Calgary's first municipal election as a city saw Wesley Fletcher Orr garner 244 votes, narrowly defeating his opponent William Henry Cushing's 220 votes, and Orr was named the first mayor of the City of Calgary.[92]

By late 19th century, the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) expanded into the interior and established posts along rivers that later developed into the modern cities of Winnipeg, Calgary and Edmonton. In 1884, the HBC established a sales shop in Calgary. HBC also built the first of the grand "original six" department stores in Calgary in 1913; others that followed were Edmonton, Vancouver, Victoria, Saskatoon, and Winnipeg.[93][94]

In October 1899 the Village of Rouleauville was incorporated by French Catholic residents south of Calgary's city limits in what is now known as Mission.[95] The town did not remain independent for long, and became the first incorporated municipality to be amalgamated into Calgary eight years later in 1907.

Turn of the 20th century

[edit]The turn of the century brought questions of provincehood the top of mind in Calgary. On September 1, 1905, Alberta was proclaimed a province with a provisional capital in Edmonton, it would be left up to the Legislature to choose the permanent location.[96] One of the first decisions of the new Alberta Legislature was the capital, and although William Henry Cushing advocated strongly for Calgary, the resulting vote saw Edmonton win the capital 16–8.[97] Calgarians were disappointed on the city not being named the capital, and focused their attention on the formation of the provincial university. However, the efforts by the community could not sway the government, and the University of Alberta was founded in the City of Strathcona, Premier Rutherford's home, which was subsequently amalgamated into the City of Edmonton in 1912.[98] Calgary was not to be left without higher education facilities as the provincial Normal School opened in the McDougall School building in 1905. In 1910, R. B. Bennett introduced a bill in the Alberta Legislature to incorporate the "Calgary University", however there was significant opposition to two degree-granting institutions in such a small province. A commission was appointed to evaluate the Calgary proposal which found the second university to be unnecessary, however, the commission did recommend the formation of the Provincial Institute of Technology and Art in Calgary (SAIT), which was formed later in 1915.[99]

Built-up areas of Calgary between 1905 and 1912 were serviced by power and water, the city continued a program of paving and sidewalk laying and with the CPR constructed a series of subways under the tracks to connect the town with streetcars. The first three motor buses hit Calgary streets in 1907, and two years later the municipally owned street railway system, fit with seven miles of track opened in Calgary. The immediately popular street railway system reached 250,000 passengers per month by 1910.[100] The privately owned MacArthur Bridge (precursor to the Centre Street Bridge over the Bow River) opened in 1907 which provided for residential expansion north of the Bow River.[101] The early-1910s saw real estate speculation hit Calgary once again, with property prices rising significantly with growing municipal investment, CPR's decision to construct a car shop at Ogden set to employ over 5,000 people, the projected arrival of the Grand Trunk Pacific and Canadian Northern Railways in the city and Calgary's growing reputation as a growing economic hub.[102] The period between 1906 and 1911 was the largest population growth period in the city's history, expanding from 11,967 to 43,704 inhabitants in the five-year period.[78][103][104] Several ambitious projects were started during this period including a new City Hall, the Hudson's Bay Department Store, the Grain Exchange Building, and the Palliser Hotel, this period also corresponded to the end of the "Sandstone City" era as steel frames and terracotta facades such as the Burns Building (1913) which were prevalent in other North American cities overtook the unique sandstone character of Calgary.[105]

Stampede City

[edit]

The growing City and enthusiastic residents were rewarded in 1908 with the federally funded Dominion Exhibition. Seeking to take advantage of the opportunity to promote itself, the city spent CA$145,000 to build six new pavilions and a racetrack.[106] It held a lavish parade as well as rodeo, horse racing, and trick roping competitions as part of the event.[107] The exhibition was a success, drawing 100,000 people to the fairgrounds over seven days despite an economic recession that afflicted the city of 25,000.[106] Calgary had previously held a number of Agricultural exhibitions dating back to 1886, and recognizing the city's enthusiasm, Guy Weadick, an American trick roper who participated in the Dominion Exhibition as part of the Miller Brothers 101 Ranch Real Wild West Show, returned to Calgary in 1912 to host the first Calgary Stampede in the hopes of establishing an event that more accurately represented the "wild west" than the shows he was a part of.[108] He initially failed to sell civic leaders and the Calgary Industrial Exhibition on his plans,[109] but with the assistance of local livestock agent H. C. McMullen, Weadick convinced businessmen Pat Burns, George Lane, A. J. McLean, and A. E. Cross to put up $100,000 to guarantee funding for the event.[107]

The Big Four, as they came to be known, viewed the project as a final celebration of their life as cattlemen.[110] The city constructed a rodeo arena on the fairgrounds and over 100,000 people attended the six-day event in September 1912 to watch hundreds of cowboys from Western Canada, the United States, and Mexico compete for $20,000 in prizes.[111] The event generated $120,000 in revenue and was hailed as a success.[107] The Calgary Stampede has continued as a civic tradition for over 100 years, marketing itself as the "greatest outdoor show on earth", with Calgarians sporting western wear for 10 days while attending the annual parade, daily pancake breakfasts.

Early oil and gas

[edit]While agriculture and railway activities were the dominant aspects of Calgary's early economy, the Turner Valley Discovery Well blew South-West of Calgary on May 14, 1914, marked the beginning of the oil and gas age in Calgary. Archibald Wayne Dingman and Calgary Petroleum Product's discovery was heralded as the "biggest oil field in the British Empire" at around 19 million cubic metres, and in a three-week period an estimated 500 oil companies sprang into existence.[112] Calgarians were enthusiastic to invest in new oil companies, with many losing life savings during the short 1914 boom in hastily formed companies.[113] Outbreak of the First World War further dampened the oil craze as more men and resources left for Europe and agricultural prices for wheat and cattle increased.[113] Turner Valley's oil fields would boom again in 1924 and 1936, and by the Second World War the Turner Valley oilfield was producing more than 95 per cent of the oil in Canada.[114] however the city would wait until 1947 for Leduc No. 1 to definitively shift Calgary to an oil and gas city. While Edmonton would see significant population and economic growth with the Leduc discovery, many corporate offices established in Calgary after Turner Valley refused to relocate north.[115] Consequently, by 1967, Calgary had more millionaires than any other city in Canada, and per capita, more cars than any city in the world.[116]

Early politics 1910s to 1940s

[edit]Early-20th-century Calgary served as a hotbed for political activity. Historically Calgarians supported the provincial and federal conservative parties, the opposite of the Liberal-friendly City of Edmonton. However, Calgarians were sympathetic to the cause of workers and supported the development of labour organizations. In 1909, the United Farmers of Alberta (UFA) formed in Edmonton through the merger of two earlier farm organizations as a non-partisan lobbying organization to represent the interests of farmers. The UFA eventually dropped its non-partisan stance when it contested the 1921 provincial election. It was elected to form the province's first non-Liberal government.[117] By that time Calgary was using single transferable vote (STV), a form of proportional representation, to elect its city councillors. Calgary was the first city in Canada to adopt PR for its city elections. Councillors were elected in one at-large district. Each voter cast just a single vote using a ranked transferable ballot. The UFA government elected in 1921 changed the provincial election law so that Calgary could elect its MLAs through PR as well. Calgary elected its MLAs through PR until 1956 and its councillors through PR until 1971 (although mostly using instant-runoff voting, not STV, in the 1960s).[118][119]

Calgary endured a six-year recession following the First World War. The high unemployment rate from reduced manufacturing demand, compounded with servicemen returning from Europe needing work, created economic and social unrest.[120] By 1921, over 2,000 men (representing 11 percent of the male workforce) were officially unemployed.[121] Labour organizations began endorsing candidates for Calgary City Council in the late 1910s and were quickly successful in electing sympathetic candidates to office, including Mayor Samuel Hunter Adams in 1920. As well the Industrial Workers of the World and its sequel, the One Big Union, found much support among Calgary workers.

The city's support of labour and agricultural groups made it a natural location for the founding meeting of the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (precursor to the New Democratic Party). The organizational meeting was held in Calgary on July 31, 1932, with attendance exceeding 1,300 people.[122] Pat Lenihan was elected to the Calgary City Council in 1939, in part due to the use of Proportional Representation in city elections. He is the only Communist Party member elected to Calgary council. (He is the subject of the book Patrick Lenihan from Irish Rebel to Founder of Canadian Public Sector Unionism, edited by Gilbert Levine (Athabasca University Press).)

In 1922, Civic Government Association formed in opposition to the power of labour groups, endorsing its own competing slate of candidates.[123] Labour's influence was short-lived on the City Council, with Labour as a whole failing to receive substantial support after 1924.[124]

Calgary gained further political prominence when R. B. Bennett's Conservative Party won the 1930 federal election and formed government and became Canada's 11th prime minister.[125] Bennett arrived in Calgary from New Brunswick in 1897, was previously the leader of the provincial Conservative Party, advocated for Calgary as the capital of Alberta, and championed the growing city.[126] Calgary had to wait another decade to have a sitting premier represent the city, when sitting Social Credit Premier William Aberhart moved from his Okotoks-High River to Calgary for the 1940 provincial election after his Okotoks-High River constituents began a recall campaign against him as their local MLA.

1960s to 1970s

[edit]

Only a little over a decade after shuttering the municipal tram lines, Calgary City Council began investigating rapid transit. In 1966 a heavy rail transit proposal was developed, however the estimated costs continued to grow rapidly, and the plan was re-evaluated in 1975. In May 1977, Calgary City Council directed that a detailed design and construction start on the south leg of a light rail transit system,[127] which opened on May 25, 1981, and dubbed the CTrain.

The University of Calgary gained autonomy as a degree-granting institution in 1966 with the passage of the Universities Act by the Alberta Legislature. The campus provided as a one-dollar lease from the City of Calgary in 1957 had previously served as a satellite campus of the University of Alberta.[citation needed]

1970s and 1980s: economic boom and bust

[edit]The 1970s energy crisis resulted in significant investment and growth in Calgary. By 1981, 45 percent of the Calgary labour force was made up of management, administrative or clerical staff, above the national average of 35 percent.[128] Calgary's population grew with the opportunity the oil boom brought. The 20-year period from 1966 to 1986 saw the population increase from 330,575 to 636,107.[129][130] Population growth became a source of pride, the June 1980 Calgary Magazine exclaimed "Welcome to Calgary! Calgary almost specializes in newcomers...".[131]

High-rise buildings were erected during the economic boom, and more office space opened in Calgary in 1979 than in New York City and Chicago combined.[132][133] The end of the oil boom is associated with the National Energy Program implemented by Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau's government and the drop in world oil prices, and the end of the construction boom in Calgary is associated with the completion of the Petro-Canada Centre in 1984. The two-tower granite Petro-Canada Centre, which some locals called "Red Square" alluding to the city's hostile view of the state-owned petroleum company, saw the larger 53-storey west tower rise to 215 m (705 ft) and become the largest building in Calgary for 26 years, and a smaller 32-storey east tower rise 130 m (430 ft).[132] The city further expanded the CTrain system, planning began in 1981, and the northeast leg of the system was to be operational in time for the 1988 Olympics.[134]

The 1980s oil glut caused by falling demand and the National Energy Program marked the end of Calgary's boom. In 1983 Calgary City Council announced service cuts to ease the $16 million deficit, 421 city employees were laid off,[135] unemployment increased from 5 to 11 percent between November 1981 and November 1982, eventually peaking at 14.9 percent in March 1983. The decline was so swift that the city's population decreased for the first time in history from April 1982 to April 1983, and 3,331 homes were foreclosed by financial institutions in 1983.[136] Low oil prices in the 1980s prevented a full economic recovery until the 1990s.[137]

In May 1980, Nelson Skalbania announced that the Atlanta Flames hockey club would relocate and become the Calgary Flames. Skalbania represented a group of Calgary businessmen that included oil magnates Harley Hotchkiss, Ralph T. Scurfield, Norman Green, Daryl Seaman and Byron Seaman, and former Calgary Stampeders player Norman Kwong.[138] Atlanta team owner Tom Cousins sold the team to Skalbania for US$16 million, a record sale price for an NHL team at the time.[139] The team reached the playoffs each year in its first 10 years in Calgary and won the team's only Stanley Cup in 1989.

Olympic legacy

[edit]Public concern existed regarding the potential long-term debt implications that had plagued Montreal following the 1976 Olympics.[140] The Calgary Olympic Development Association led the bid for Calgary and spent two years building local support for the project, selling memberships to 80,000 of the city's 600,000 residents.[141] It secured CA$270 million in funding from the federal and provincial governments while civic leaders, including Mayor Ralph Klein, crisscrossed the world attempting to woo International Olympic Committee (IOC) delegates.[142] Calgary was one of three finalists, opposed by the Swedish community of Falun and Italian community of Cortina d'Ampezzo.[142] On September 30, 1981, the International Olympic Committee voted to give Calgary the right to host the 1988 Olympic Winter Games, becoming the first Canadian host for the winter games.[143]

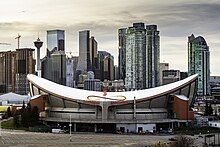

The Games' five primary venues were all purpose-built, however, at significant cost.[144] The Olympic Saddledome was the primary venue for ice hockey and figure skating. Located at Stampede Park, the facility was expected to cost $83 million, but cost overruns pushed the facility to nearly $100 million.[145] The Olympic Oval was built on the campus of the University of Calgary. It was the first fully enclosed 400-metre speed skating venue in the world as it was necessary to protect against the possibility of either bitter cold temperatures or ice-melting chinook winds.[146] Seven world and three Olympic records were broken during the Games, resulting in the facility earning praise as "the fastest ice on Earth".[145] Canada Olympic Park was built on the western outskirts of Calgary and hosted bobsled, luge, ski jumping and freestyle skiing. It was the most expensive facility built for the games, costing $200 million.[145]

Despite Canada failing to earn a gold medal in the Games, the events proved to be a major economic boom for the city, which had fallen into its worst recession in 40 years following the collapse of both oil and grain prices in the mid-1980s.[147][148] A report prepared for the city in January 1985 estimated the games would create 11,100 man-years of employment and generate CA$450-million in salaries and wages.[149] In its post-Games report, OCO'88 estimated the Olympics created CA$1.4 billion in economic benefits across Canada during the 1980s, 70 percent within Alberta, as a result of capital spending, increased tourism and new sporting opportunities created by the facilities.[150]

1990s to present

[edit]Thanks in part to escalating oil prices, the economy in Calgary and Alberta was booming until the end of 2009, and the region of nearly 1.1 million people was home to the fastest-growing economy in the country.[151] While the oil and gas industry comprise an important part of the economy, the city has invested a great deal into other areas such as tourism and high-tech manufacturing. Over 3.1 million people now visit the city annually[152] for its many festivals and attractions, especially the Calgary Stampede. The nearby mountain resort towns of Banff, Lake Louise, and Canmore are also becoming increasingly popular with tourists. Other modern industries include light manufacturing, high-tech, film, e-commerce, transportation, and services.

Widespread flooding throughout southern Alberta, including on the Bow and Elbow rivers, forced the evacuation of over 75,000 city residents on June 21, 2013, and left large areas of the city, including downtown, without power.[153][154]

Geography

[edit]

Calgary is at the transition zone between the Canadian Rockies foothills and the Canadian Prairies. The city lies within the foothills of the Parkland Natural Region and the Grasslands Natural Region.[155] Downtown Calgary is about 1,042.4 m (3,420 ft) above sea level,[6] and the airport is 1,076 m (3,531 ft).[156] In 2011, the city covered a land area of 825.29 km2 (318.65 sq mi).[157] Calgary is in southern Alberta and also next to the Rocky mountains.

Two rivers and two creeks run through the city. The Bow River is the larger, and it flows from the west to the south. The Elbow River flows northwards from the south until it converges with the Bow River at the historic site of Fort Calgary near downtown. Nose Creek flows into Calgary from the northwest, then south to join the Bow River several kilometres east of the Elbow-Bow confluence. Fish Creek flows into Calgary from the southwest and converges with the Bow River near McKenzie Lake.

The City of Calgary, 848 km2 (327 sq mi) in size,[158] consists of an inner city surrounded by suburban communities of various density.[159] The city is immediately surrounded by two municipal districts – Foothills County to the south and Rocky View County to the north, west and east. Proximate urban communities beyond the city within the Calgary Metropolitan Region include: the City of Airdrie to the north; the City of Chestermere, the Town of Strathmore and the Hamlet of Langdon to the east; the towns of Okotoks and High River to the south; and the Town of Cochrane to the northwest.[160] Numerous rural subdivisions are located within the Elbow Valley, Springbank and Bearspaw areas to the west and northwest.[161][162][163] The Tsuu T'ina Nation Indian Reserve No. 145 borders Calgary to the southwest.[160]

Over the years, the city has made many land annexations to facilitate growth. In the most recent annexation of lands from the surrounding Rocky View County, completed in July 2007, the city annexed Shepard, a former hamlet, and placed its boundaries adjacent to the Hamlet of Balzac and City of Chestermere, and very close to the City of Airdrie.[164]

Flora and fauna

[edit]Numerous plant and animal species are found within and around Calgary. The Rocky Mountain Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii var. glauca) comes near the eastern limit of its range at Calgary.[165] Another conifer of widespread distribution found in the Calgary area is the white spruce (Picea glauca).[166] Animals that can be found in and around Calgary include white-tail deer, coyotes, North American porcupines, moose, bats, rabbits, mink, weasels, black bears, raccoons, skunks, and cougars.[167]

Neighbourhoods

[edit]

The downtown region of the city consists of five neighbourhoods: Eau Claire (including the Festival District), the Downtown West End, the Downtown Commercial Core, Chinatown, and the Downtown East Village (also part of the Rivers District). The commercial core is itself divided into a number of districts, including the Stephen Avenue Retail Core, the Entertainment District, the Arts District, and the Government District. Distinct from downtown and south of 9th Avenue is Calgary's densest neighbourhood, the Beltline. The area includes a number of communities, such as Connaught, Victoria Crossing, and a portion of the Rivers District. The Beltline is the focus of major planning and rejuvenation initiatives on the part of the municipal government to increase the density and liveliness of Calgary's centre.[168]

Directly radiating from the downtown core is the first of the inner-city communities. These include Crescent Heights, Hounsfield Heights/Briar Hill, Hillhurst/Sunnyside (including Kensington BRZ), Bridgeland, Renfrew, Mount Royal, Scarboro, Sunalta, Mission, Ramsay and Inglewood and Albert Park/Radisson Heights directly to the east. The inner city is, in turn, surrounded by relatively dense and established neighbourhoods such as Rosedale and Mount Pleasant to the north; Bowness, Parkdale, Shaganappi, Westgate and Glendale to the west; Park Hill, South Calgary (including Marda Loop), Bankview, Altadore, and Killarney to the south; and Forest Lawn/International Avenue to the east. Lying beyond these, and usually separated from one another by highways, are suburban communities including Evergreen, Somerset, Auburn Bay, Country Hills, Sundance, Chaparral, Riverbend, and McKenzie Towne. In all, there are over 180 distinct neighbourhoods within the city limits.[169]

Several of Calgary's neighbourhoods were initially separate municipalities that were annexed by the city as it grew. These include Bowness, Montgomery, Midnapore, Shepard, and Forest Lawn.

Climate

[edit]Calgary experiences a semi-monsoonal humid continental climate (Köppen climate classification Dwb, Trewartha climate classification Dclo) within the city and a semi-monsoonal subarctic climate (Köppen Dwc, Trewartha Eolo) to the west of the city, largely due to an increase in elevation.[170] The city has warm summers and very cold, dry (though highly variable) winters.[171] It falls into the NRC Plant Hardiness Zone 4a.[172] According to Environment Canada, average daily temperatures in Calgary range from 16.9 °C (62.4 °F) in July to −7.6 °C (18.3 °F) in January.[173] Average temperatures in Springbank Airport (slightly west of Calgary) range from 14.8 °C (58.6 °F) in July to −8.2 °C (17.2 °F) in January.[170]

Winters are cold, and the air temperature drops to or below −20 °C (−4 °F) on average 22 days of the year and −30 °C (−22 °F) on average of 3.7 days of the year, but are frequently broken up by warm, dry chinook winds that blow into Alberta over the mountains. These winds can raise the winter temperature by 20 °C (36 °F), and as much as 30 °C (54 °F) in just a few hours and may last several days.[174] As well, Calgary's proximity to the Rocky Mountains affects winter temperatures with a mixture of lows and highs, and tends to result in a mild winter for a city in the Prairie Provinces. Temperatures are also affected by the wind chill factor; Calgary's average wind speed is 14.2 km/h (8.8 mph), one of the highest in Canadian cities.[175]

In summer, daytime temperatures range from 10 to 25 °C (50 to 77 °F) and exceed 30 °C (86 °F) an average of 5.1 days in June, July, and August, and occasionally as late as September or as early as May, and in winter drop below or at −30 °C (−22 °F) 3.7 days of the year. As a consequence of Calgary's high elevation and aridity, summer days are often not humid, unlike many other major cities in Canada. Summer evenings also tend to cool off, with monthly average low temperatures reaching 9 to 10 °C (48 to 50 °F) throughout the summer months.[173]

Calgary has the sunniest days year-round of Canada's 100 largest cities, with slightly over 332 days of sun;[173] it has on average 2,396 hours of sunshine annually,[173] with an average relative humidity of 55% in the winter and 45% in the summer (15:00 MST).[173]

Calgary International Airport in the northeastern section of the city receives an average of 418.8 mm (16.49 in) of precipitation annually, with 326.4 mm (12.85 in) of that occurring in the form of rain, and 128.8 cm (50.7 in) as snow.[173] The most rainfall occurs in June and the most snowfall in March.[173] Calgary has also recorded snow every month of the year.[176] It last snowed in July on July 15, 1999.[177]

Thunderstorms can be frequent and sometimes severe[178] with most of them occurring in the summer months. Calgary lies within Alberta's Hailstorm Alley and is prone to damaging hailstorms every few years. A hailstorm that struck Calgary on September 7, 1991, was one of the most destructive natural disasters in Canadian history, with over $400 million in damage.[179] Being west of the dry line on most occasions, tornadoes are rare in the region.

The highest temperature ever recorded in Calgary was 36.7 °C (98.1 °F) on August 10, 2018.[180] The lowest temperature ever recorded was −45.0 °C (−49.0 °F) on February 4, 1893.[173]

On November 15, 2021, Calgary City Council voted to declare a climate emergency. A climate emergency declaration is a resolution passed by a governing body such as a city council. It puts the local government on record in support of emergency action to respond to climate change and recognizes the pace and scale of action needed.[181]

| Climate data for Calgary (Calgary International Airport) WMO ID: 71877; coordinates 51°06′50″N 114°01′13″W / 51.11389°N 114.02028°W; elevation: 1,084.1 m (3,557 ft); 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1881–present[a] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high humidex | 17.3 | 21.9 | 25.2 | 27.2 | 31.6 | 37.0 | 36.9 | 36.4 | 32.9 | 28.7 | 22.6 | 19.4 | 37.0 |

| Record high °C (°F) | 17.6 (63.7) |

22.6 (72.7) |

25.4 (77.7) |

29.4 (84.9) |

32.4 (90.3) |

36.3 (97.3) |

36.3 (97.3) |

36.7 (98.1) |

33.3 (91.9) |

29.4 (84.9) |

23.1 (73.6) |

19.5 (67.1) |

36.7 (98.1) |

| Mean maximum °C (°F) | 8.5 (47.3) |

9.4 (49.0) |

14.1 (57.4) |

21.1 (69.9) |

25.9 (78.7) |

26.9 (80.4) |

30.4 (86.7) |

30.4 (86.8) |

27.4 (81.4) |

21.2 (70.2) |

13.0 (55.4) |

7.6 (45.6) |

32.5 (90.5) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | −1.5 (29.3) |

0.1 (32.2) |

3.8 (38.8) |

10.8 (51.4) |

16.4 (61.5) |

19.7 (67.5) |

23.5 (74.3) |

23.1 (73.6) |

18.3 (64.9) |

11.1 (52.0) |

4.1 (39.4) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

10.8 (51.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −7.6 (18.3) |

−5.9 (21.4) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

4.5 (40.1) |

9.9 (49.8) |

13.7 (56.7) |

16.9 (62.4) |

16.2 (61.2) |

11.5 (52.7) |

4.9 (40.8) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

−6.3 (20.7) |

4.5 (40.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −13.5 (7.7) |

−11.8 (10.8) |

−8.1 (17.4) |

−1.9 (28.6) |

3.4 (38.1) |

7.7 (45.9) |

10.2 (50.4) |

9.2 (48.6) |

4.7 (40.5) |

−1.3 (29.7) |

−7.5 (18.5) |

−12.1 (10.2) |

−1.8 (28.8) |

| Mean minimum °C (°F) | −29.0 (−20.2) |

−24.8 (−12.6) |

−22.3 (−8.1) |

−10.8 (12.5) |

−3.5 (25.7) |

1.9 (35.4) |

5.1 (41.1) |

3.2 (37.8) |

−2.1 (28.3) |

−10.5 (13.1) |

−19.1 (−2.4) |

−25.9 (−14.7) |

−31.5 (−24.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −44.4 (−47.9) |

−45 (−49) |

−37.2 (−35.0) |

−30 (−22) |

−16.7 (1.9) |

−3.3 (26.1) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

−3.2 (26.2) |

−13.3 (8.1) |

−25.7 (−14.3) |

−35 (−31) |

−42.8 (−45.0) |

−45 (−49) |

| Record low wind chill | −52.1 | −52.6 | −44.7 | −37.1 | −23.7 | −5.8 | 0.0 | −4.1 | −12.5 | −34.3 | −47.9 | −55.1 | −55.1 |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 10.0 (0.39) |

11.8 (0.46) |

17.7 (0.70) |

29.6 (1.17) |

61.1 (2.41) |

112.7 (4.44) |

65.7 (2.59) |

53.8 (2.12) |

37.1 (1.46) |

17.1 (0.67) |

16.3 (0.64) |

12.5 (0.49) |

445.4 (17.54) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 0.1 (0.00) |

0.1 (0.00) |

1.1 (0.04) |

12.6 (0.50) |

52.5 (2.07) |

112.5 (4.43) |

65.7 (2.59) |

53.5 (2.11) |

33.8 (1.33) |

8.3 (0.33) |

1.7 (0.07) |

0.3 (0.01) |

342.2 (13.47) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 16.6 (6.5) |

16.9 (6.7) |

23.8 (9.4) |

22.9 (9.0) |

9.6 (3.8) |

0.2 (0.1) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

2.2 (0.9) |

11.5 (4.5) |

18.8 (7.4) |

16.3 (6.4) |

138.7 (54.6) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 7.4 | 7.8 | 8.8 | 9.8 | 11.1 | 14.5 | 12.9 | 10.4 | 8.3 | 7.8 | 8.0 | 7.2 | 114.0 |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 0.3 | 0.22 | 0.83 | 4.8 | 10.0 | 14.5 | 12.9 | 10.0 | 7.7 | 4.4 | 1.5 | 0.22 | 67.4 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.2 cm) | 7.8 | 7.9 | 9.3 | 7.0 | 2.4 | 0.08 | 0.0 | 0.13 | 0.96 | 4.6 | 7.1 | 7.7 | 55.0 |

| Average relative humidity (%) (at 1500 LST) | 55.7 | 54.7 | 50.2 | 42.7 | 43.8 | 49.2 | 46.8 | 44.3 | 44.3 | 45.3 | 54.2 | 56.3 | 49.0 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 119.5 | 144.6 | 177.2 | 220.2 | 249.4 | 269.9 | 314.1 | 284.0 | 207.0 | 175.4 | 121.1 | 114.0 | 2,396.3 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 45.6 | 51.3 | 48.2 | 53.1 | 51.8 | 54.6 | 63.1 | 62.9 | 54.4 | 52.7 | 45.0 | 46.0 | 52.4 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Source: Environment and Climate Change Canada,[173] Meteoblue (for monthly mean minima and maxima),[182] Extreme Weather Watch (for yearly mean minima and maxima),[183][184] and Weather Atlas[185] (for UV index) | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Springbank Hill (Calgary/Springbank Airport) WMO ID: 71860; coordinates 51°06′11″N 114°22′28″W / 51.10306°N 114.37444°W; elevation: 1,200.9 m (3,940 ft); 1995-2024 normals (see notes) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high humidex | 15.7 | 21.3 | 22.9 | 25.7 | 30.6 | 31.9 | 34.1 | 34.0 | 31.0 | 26.4 | 20.5 | 17.1 | 34.1 |

| Record high °C (°F) | 16.5 (61.7) |

22.1 (71.8) |

23.8 (74.8) |

26.5 (79.7) |

33.0 (91.4) |

31.0 (87.8) |

33.8 (92.8) |

32.1 (89.8) |

30.6 (87.1) |

27.1 (80.8) |

20.4 (68.7) |

17.9 (64.2) |

33.8 (92.8) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | −2.0 (28.4) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

2.9 (37.2) |

9.1 (48.4) |

14.8 (58.6) |

18.7 (65.7) |

22.7 (72.9) |

22.0 (71.6) |

17.8 (64.0) |

10.5 (50.9) |

2.8 (37.0) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

9.7 (49.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −8.4 (16.9) |

−7.0 (19.4) |

−3.5 (25.7) |

2.3 (36.1) |

7.8 (46.0) |

12.0 (53.6) |

15.3 (59.5) |

14.3 (57.7) |

10.2 (50.4) |

3.6 (38.5) |

−3.3 (26.1) |

−8.2 (17.2) |

2.9 (37.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −14.8 (5.4) |

−14.6 (5.7) |

−9.9 (14.2) |

−4.5 (23.9) |

0.8 (33.4) |

5.3 (41.5) |

7.9 (46.2) |

6.6 (43.9) |

2.6 (36.7) |

−3.3 (26.1) |

−9.4 (15.1) |

−14.2 (6.4) |

−4.0 (24.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −42.8 (−45.0) |

−41.6 (−42.9) |

−36.3 (−33.3) |

−21.7 (−7.1) |

−14.1 (6.6) |

−6.1 (21.0) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

−5.9 (21.4) |

−9.8 (14.4) |

−29.1 (−20.4) |

−36.5 (−33.7) |

−41.6 (−42.9) |

−42.8 (−45.0) |

| Record low wind chill | −56.0 | −56.0 | −48.0 | −27.0 | −20.0 | −10.0 | −4.0 | −8.0 | −14.0 | −38.0 | −48.0 | −57.0 | −57.0 |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 9.6 (0.38) |

9.4 (0.37) |

17.4 (0.69) |

38.1 (1.50) |

67.6 (2.66) |

108.9 (4.29) |

57.5 (2.26) |

62.3 (2.45) |

44.6 (1.76) |

24.4 (0.96) |

14.2 (0.56) |

11.2 (0.44) |

465.2 (18.32) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 0.2 (0.01) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.4 (0.02) |

9.3 (0.37) |

49.5 (1.95) |

106.7 (4.20) |

66.9 (2.63) |

78.0 (3.07) |

45.5 (1.79) |

7.0 (0.28) |

2.4 (0.09) |

0.3 (0.01) |

366.2 (14.42) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 12.7 (5.0) |

14.7 (5.8) |

21.7 (8.5) |

19.0 (7.5) |

12.4 (4.9) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

5.3 (2.1) |

11.6 (4.6) |

17.4 (6.9) |

12.4 (4.9) |

127.3 (50.2) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 5.8 | 5.7 | 7.5 | 8.1 | 11.6 | 14.5 | 12.8 | 12.4 | 9.4 | 7.2 | 6.0 | 5.3 | 106.3 |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 0.17 | 0.04 | 0.48 | 3.5 | 9.7 | 14.5 | 12.8 | 12.3 | 8.8 | 4.3 | 0.91 | 0.23 | 67.73 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.2 cm) | 6.0 | 5.9 | 7.6 | 5.8 | 3.0 | 0.0 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 1.4 | 3.9 | 5.9 | 5.4 | 45.0 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 58.6 | 56.0 | 50.3 | 43.3 | 45.7 | 50.8 | 48.2 | 49.2 | 47.8 | 46.5 | 57.1 | 60.4 | 51.2 |

| Source 1: Environment Canada[186] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Canada 30 Year Averages[187] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]

In the 2021 Census of Population conducted by Statistics Canada, the City of Calgary had a population of 1,306,784 living in 502,301 of its 531,062 total private dwellings, a change of 5.5% from its 2016 population of 1,239,220. With a land area of 820.62 km2 (316.84 sq mi), it had a population density of 1,592.4/km2 (4,124.4/sq mi) in 2021.[5]

At the census metropolitan area (CMA) level in the 2021 census, the Calgary CMA had a population of 1,481,806 living in 563,440 of its 594,513 total private dwellings, a change of 6.4% from its 2016 population of 1,392,609. With a land area of 5,098.68 km2 (1,968.61 sq mi), it had a population density of 290.6/km2 (752.7/sq mi) in 2021.[8]

The population of the City of Calgary according to its 2019 municipal census is 1,285,711,[188] a change of 1.4% from its 2018 municipal census population of 1,267,344.[189]

In the 2016 Census of Population conducted by Statistics Canada, the City of Calgary had a population of 1,239,220 living in 466,725 of its 489,650 total private dwellings, a change of 13% from its 2011 population of 1,096,833. With a land area of 825.56 km2 (318.75 sq mi), it had a population density of 1,501.1/km2 (3,887.7/sq mi) in 2016.[190] Calgary was ranked first among the three cities in Canada that saw their population grow by more than 100,000 people between 2011 and 2016. During this time, Calgary saw a population growth of 142,387 people, followed by Edmonton at 120,345 people and Toronto at 116,511 people.[191]

The Calgary census metropolitan area (CMA) is the fourth-largest CMA in Canada and the largest in Alberta. It had a population of 1,392,609 in the 2016 Census compared to its 2011 population of 1,214,839. Its five-year population change of 14.6 percent was the highest among all CMAs in Canada between 2011 and 2016. With a land area of 5,107.55 km2 (1,972.04 sq mi), the Calgary CMA had a population density of 272.7/km2 (706.2/sq mi) in 2016.[192] Statistics Canada's latest estimate of the Calgary CMA population, as of July 1, 2017, is 1,488,841.[193]

In 2015, the population within an hour commuting distance of the city was 1,511,755.[194]

As a consequence of the large number of corporations, as well as the presence of the energy sector in Alberta, Calgary has a median family income of $104,530.[195]

The 2021 census reported that immigrants (individuals born outside Canada) comprise 430,640 persons or 33.3% of the total population of Calgary. Of the total immigrant population, the top countries of origin were Philippines (65,430 persons or 15.2%), India (56,515 persons or 13.1%), China (36,240 persons or 8.4%), United Kingdom (20,415 persons or 4.7%), Pakistan (18,375 persons or 4.3%), Vietnam (15,395 persons or 3.6%), Nigeria (12,450 persons or 2.9%), United States of America (10,890 persons or 2.5%), Hong Kong (10,775 persons or 2.5%), and South Korea (8,210 persons or 1.9%).[196]

Ethnicity

[edit]Pan-ethnic breakdown of Calgary from the 2021 census[196]

According to the 2016 Census, 60% of Calgary's population was white or European, 4% were Indigenous, and 36.2% belonged to a visible minority group (non-white and non-Indigenous). Among those of European origin, the most frequently reported ethnic backgrounds were British, German, Irish, French, and Ukrainian.

Among visible minorities, South Asians (ethnic backgrounds mainly from India and Pakistan) make up the largest group (9.5%), followed by Chinese (6.8%) and Filipinos (5.5%). 5.4% were of African or Caribbean origin, 3.5% was of West Asian or Middle Eastern origin, while 2.6% of the population was of Latin American origin. Of the largest Canadian cities, Calgary ranked fourth in the proportion of visible minorities, behind Toronto, Vancouver, and Winnipeg. 20.7% of the population identified as "Canadian" in ethnic origin.[197]

| Panethnic group | 2021[198] | 2016 | 2011 | 2006 | 2001 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | |

| European | 715,725 | 55.41% | 744,625 | 60.91% | 727,935 | 67.26% | 722,595 | 73.77% | 688,465 | 79.03% |

| South Asian | 141,660 | 10.97% | 115,795 | 9.47% | 81,180 | 7.5% | 56,210 | 5.74% | 36,370 | 4.17% |

| Southeast Asian | 110,610 | 8.56% | 89,260 | 7.3% | 67,880 | 6.27% | 40,325 | 4.12% | 28,605 | 3.28% |

| East Asian | 109,615 | 8.49% | 103,640 | 8.48% | 87,390 | 8.07% | 76,565 | 7.82% | 59,020 | 6.78% |

| African | 70,680 | 5.47% | 51,515 | 4.21% | 31,870 | 2.94% | 20,540 | 2.1% | 13,370 | 1.53% |

| Middle Eastern | 45,885 | 3.55% | 37,800 | 3.09% | 25,215 | 2.33% | 17,175 | 1.75% | 11,300 | 1.3% |

| Indigenous | 41,350 | 3.2% | 35,195 | 2.88% | 28,905 | 2.67% | 24,425 | 2.49% | 19,765 | 2.27% |

| Latin American | 31,855 | 2.47% | 26,265 | 2.15% | 19,870 | 1.84% | 13,120 | 1.34% | 8,525 | 0.98% |

| Other/Multiracial | 24,400 | 1.89% | 18,305 | 1.5% | 11,990 | 1.11% | 8,525 | 0.87% | 5,735 | 0.66% |

| Total responses | 1,291,770 | 98.85% | 1,222,405 | 98.64% | 1,082,230 | 98.67% | 979,485 | 99.12% | 871,140 | 99.12% |

| Total population | 1,306,784 | 100% | 1,239,220 | 100% | 1,096,833 | 100% | 988,193 | 100% | 878,866 | 100% |

| Note: Totals greater than 100% due to multiple origin responses | ||||||||||

Religion

[edit]According to the 2021 census, religious groups in Calgary included:[196]

- Christianity (575,250 persons or 44.5%)

- Irreligion (499,375 persons or 38.7%)

- Islam (95,925 persons or 7.4%)

- Sikhism (49,465 persons or 3.8%)

- Hinduism (33,450 persons or 2.6%)

- Buddhism (20,855 persons or 1.6%)

- Judaism (6,390 persons or 0.5%)

- Indigenous Spirituality (1,370 persons or 0.1%)

- Other (9,695 persons or 0.8%)

Economy

[edit]| Industry | Calgary | Alberta |

|---|---|---|

| Agriculture | 6.1% | 10.9% |

| Manufacturing | 15.8% | 15.8% |

| Trade | 15.9% | 15.8% |

| Finance | 6.4% | 5.0% |

| Health and education | 25.1% | 18.8% |

| Business services | 25.1% | 18.8% |

| Other services | 16.5% | 18.7% |

| Rate | Calgary | Alberta | Canada |

|---|---|---|---|

| Employment | 66.9% | 66.3% | 61.2% |

| Unemployment | 10.3% | 9.0% | 6.8% |

| Participation | 74.6% | 72.9% | 65.6% |

Calgary is recognized as a leader in the Canadian oil and gas industry, and its economy expanded at a significantly higher rate than the overall Canadian economy (43% and 25%, respectively) over the ten-year period from 1999 to 2009.[201] Its high personal and family incomes,[14][202] low unemployment and high GDP per capita[203] have all benefited from increased sales and prices due to a resource boom,[201] and increasing economic diversification.

Calgary benefits from a relatively strong job market in Alberta and is part of the Calgary–Edmonton Corridor, one of the fastest-growing regions in the country. It is the head office for many major oil and gas-related companies, and many financial service businesses have grown up around them. Small business and self-employment levels also rank amongst the highest in Canada.[202] Calgary is a distribution and transportation hub[204] with high retail sales.[202]

Calgary's economy is decreasingly dominated by the oil and gas industry, although it is still the single largest contributor to the city's GDP. In 2006, Calgary's real GDP (in constant 1997 dollars) was CA$52.386 billion, of which oil, gas and mining contributed 12%.[205] The larger oil and gas companies are BP Canada, Canadian Natural Resources Limited, Cenovus Energy, Encana, Imperial Oil, Suncor Energy, Shell Canada, Husky Energy, TransCanada, and Nexen, making the city home to 87% of Canada's oil and natural gas producers and 66% of coal producers.[206]

As of November 2016, the city had a labour force of 901,700 (a 74.6% participation rate) and 10.3% unemployment rate.[207][208][209]

In 2013, Calgary's four largest industries by employee count were "Trade" (with 112,800 employees), "Professional, Scientific and Technical Services" (100,800 employees), "Health Care and Social Assistance" (89,200 employees), and "Construction" (81,500 employees).[210]

In 2006, the top three private sector employers in Calgary were Shaw Communications (7,500 employees), Nova Chemicals (4,945) and Telus (4,517).[211] Companies rounding out the top ten were Mark's Work Wearhouse, the Calgary Co-op, Nexen, Canadian Pacific Railway, CNRL, Shell Canada and Dow Chemical Canada.[211] The top public sector employers in 2006 were the Calgary Zone of the Alberta Health Services (22,000), the City of Calgary (12,296) and the Calgary Board of Education (8,000).[211] Public sector employers rounding out the top five were the University of Calgary and the Calgary Roman Catholic Separate School Division.[211]

In Canada, Calgary has the second-highest concentration of head offices in Canada (behind Toronto), the most head offices per capita, and the highest head office revenue per capita.[14][202] Some large employers with Calgary head offices include Canada Safeway Limited, Westfair Foods Ltd., Suncor Energy, Agrium, Flint Energy Services Ltd., Shaw Communications, and Canadian Pacific Kansas City.[212] CPR moved its head office from Montreal in 1996 and Imperial Oil moved from Toronto in 2005. Encana's new 58-floor corporate headquarters, the Bow, became the tallest building in Canada outside of Toronto.[213] In 2001, the city became the corporate headquarters of the TSX Venture Exchange.

WestJet is headquartered close to the Calgary International Airport,[214] and Enerjet has its headquarters on the airport grounds.[215] Prior to their dissolution, Canadian Airlines[216] and Air Canada's subsidiary Zip were also headquartered near the city's airport.[217] Although its main office is now based in Yellowknife, Canadian North, purchased from Canadian Airlines in September 1998, still maintains operations and charter offices in Calgary.[218][219]

One of Canada's largest accounting firms, MNP LLP, is also headquartered in Calgary.[220]

According to a report by Alexi Olcheski of Avison Young published in August 2015, vacancy rates rose to 11.5 percent in the second quarter of 2015 from 8.3 percent in 2014. Oil and gas company office spaces in downtown Calgary are subleasing 40 percent of their overall vacancies.[221] H&R Real Estate Investment Trust, which owns the 58-storey, 158,000-square-metre Bow Tower, claims the building was fully leased. Tenants such as Suncor "have been letting staff and contractors go in response to the downturn".[221]

Arts and culture

[edit]Calgary was designated as one of Canada's cultural capitals in 2012.[222] While many Calgarians continue to live in the city's suburbs, more central neighbourhoods such as Kensington, Inglewood, Forest Lawn, Bridgeland, Marda Loop, the Mission District, and especially the Beltline, have become more popular and density in those areas has increased.[223]

Stage

[edit]Calgary is the site of the Southern Alberta Jubilee Auditorium performing arts, culture and community facility. The auditorium is one of two "twin" facilities in the province, the other is the Northern Alberta Jubilee Auditorium in Edmonton, each being locally known as the "Jube." The 2,538-seat auditorium was opened in 1957[224] and has been host to hundreds of musical theatre, theatrical, stage and local productions. The Calgary Jube is the resident home of the Alberta Ballet Company, the Calgary Opera, and the annual civic Remembrance Day ceremonies. Both auditoriums operate 365 days a year and are run by the provincial government. Both received major renovations as part of the province's centennial in 2005.[224]

The city is also home to a number of performing arts spaces, such as Arts Commons, which is a 400,000 square foot performing arts complex housing the Jack Singer Concert Hall, Martha Cohen Theatre, Max Bell Theatre, Big Secret Theatre, and Motel Theatre, the Pumphouse Theatre, which houses the Victor Mitchell and Joyce Doolittle theatres, The GRAND, the Bella Concert Hall, the Wright Theatre, Vertigo Theatre, Stage West Theatre, Lunchbox Theatre, and several other smaller venues.

Theatre

[edit]Some large theatre companies share Calgary's Arts Commons building, including One Yellow Rabbit, Theatre Calgary, and Alberta Theatre Projects. The Grand is a culture house dedicated to the contemporary live arts. Other companies, groups, and collectives operate in niche theatres, such as Storybook Theatre (children's theatre), Sundog Storytellers (immersive theatre), and The Shakespeare Company.

Calgary is the birthplace of the Theatresports, which are improvisational theatre games.[225]

Music

[edit]Every three years, Calgary hosts the Honens International Piano Competition (formerly known as the Esther Honens International Piano Competition). The finalists of the competition perform piano concerti with the Calgary Philharmonic Orchestra; the laureate is awarded a cash prize (currently $100,000.00 CDN, the largest cash award of any international piano competition), and a three-year career development program. Honens is an integral component of the classical music scene in Calgary.

A number of marching bands are based in Calgary. They include the Calgary Round-Up Band, the Calgary Stetson Show Band, the Bishop Grandin Marching Ghosts, and the six-time World Association for Marching Show Bands champions, the Calgary Stampede Showband, as well as military bands including the Band of HMCS Tecumseh, the King's Own Calgary Regiment Band, and the Regimental Pipes and Drums of The Calgary Highlanders. There are many other civilian pipe bands in the city, notably the Calgary Police Service Pipe Band.[226]

Calgary is also home to a choral music community, including a variety of amateur, community, and semi-professional groups. Some of the mainstays include the Mount Royal Choirs from the Mount Royal University Conservatory, the Calgary Boys' Choir, the Calgary Girls Choir, the Youth Singers of Calgary, the Cantaré Children's Choir, Luminous Voices Music Society, Spiritus Chamber Choir, and pop-choral group Revv52.[227][228][229]

Dance

[edit]The Alberta Ballet is Canada's third-largest dance company. Under Jean Grand-Maître's artistic direction, the Alberta Ballet is at the forefront both at home and internationally. Jean Grand-Maître is well known for his successful portrait series collaborations with pop artists like Joni Mitchell, Elton John, and Sarah McLachlan. The Alberta Ballet resides in the Nat Christie Centre.[230][231][232]

Other dance companies include Springboard Performance, which hosts the annual Fluid Movement Arts Festival,[233] Decidedly Jazz Danceworks, which opened its new $25-million facility in 2016 in collaboration with the Kahanoff Foundation,[234] as well as a host of others, including European folk dance ensembles, Afro-based dance companies, and diasporic dance companies.

Film and television

[edit]Numerous films have been shot in Calgary and the surrounding area, including The Assassination of Jesse James, Brokeback Mountain, Dances with Wolves, Doctor Zhivago, Inception, Legends of the Fall, Unforgiven, The Revenant, and Cool Runnings.[235][236] Ghostbusters: Afterlife was filmed in downtown Calgary and Inglewood in 2019.[237] Television shows include Fargo,[238] Black Summer,[239] Wyonna Earp[240] Wild Roses,[241] and The Last of Us.

Print media

[edit]The Calgary Herald and the Calgary Sun are the main newspapers in Calgary. Global, City, CTV and CBC television networks have local studios in the city.

Visual art

[edit]Visual and conceptual artists like the art collective United Congress are active in the city. There are a number of art galleries in the downtown along Stephen Avenue; the SoDo (South of Downtown) Design District; the 17 Avenue corridor; the neighbourhood of Inglewood, including the Esker Foundation.[242][243] There are also various art installations in the +15 system in downtown Calgary.[244]

Libraries

[edit]

The Calgary Public Library is the city's public library network, with 21 branches loaning books, e-books, CDs, DVDs, Blu-rays, audiobooks, and more. Based on borrowing, the library is Canada's second-largest and North America's sixth-largest municipal library. The new flagship branch, the 22,000 m2 (240,000 sq ft) Calgary Central Library in Downtown East Village, opened on November 1, 2018.[246]

Museums

[edit]Several museums are in the city. The Glenbow Museum is western Canada's largest and includes an art gallery and First Nations gallery.[247] Other major museums include the Chinese Cultural Centre (at 6,500 m2 (70,000 sq ft), the largest stand-alone cultural centre in Canada),[248] Canada's Sports Hall of Fame (at Canada Olympic Park), The Military Museums, the National Music Centre and The Hangar Flight Museum.

Festivals

[edit]

Calgary hosts a number of annual festivals and events. These include the Calgary International Film Festival, the Calgary Folk Music Festival, the Calgary Performing Arts Festival (formerly Kiwanis Music Festival),[251] FunnyFest Calgary Comedy Festival, Sled Island music festival, Beakerhead, the Greek festival, Carifest, Wordfest, the Lilac Festival, GlobalFest, Otafest, the Calgary Comic and Entertainment Expo, FallCon, the Calgary Fringe Festival, Summerstock, Expo Latino, Calgary Pride, Calgary International Spoken Word Festival,[252] and many other cultural and ethnic festivals. The Calgary International Film Festival is also held annually as well as the International Festival of Animated Objects.[253]

Calgary's best-known event is the Calgary Stampede, which has occurred each July, with the exception of the year 2020, since 1912. It is one of the largest festivals in Canada, with a 2005 attendance of 1,242,928 at the 10-day rodeo and exhibition.[249]

Arts education

[edit]Calgary is also home to several post-secondary institutions that provide credit and non-credit instruction in the arts, including the Alberta University of the Arts (formerly Alberta College of Art and Design),[254] the School of Creative and Performing Arts at the University of Calgary,[255] the Mount Royal University Conservatory,[256] and Ambrose University.

Attractions

[edit]

Downtown Calgary features an eclectic mix of restaurants and bars, cultural venues, public squares and shopping. Downtown attractions include the Calgary Tower, Wilder Institute/Calgary Zoo, National Music Centre, Calgary Telus Convention Centre, Chinatown district, Arts Commons, Central Library, St. Patrick's Island, Glenbow Museum, the Art Gallery of Calgary (AGC), Olympic Plaza, the Calgary Stampede grounds and military museums, and various other high rises. Notable shopping areas include the Core Centre, Stephen Avenue and the Eau Claire Market. The Peace Bridge spans the Bow River in the downtown region. The region is also home to Prince's Island Park, an urban park located just north of the Eau Claire district. At 1.0 ha (2.5 acres), the Devonian Gardens is one of the largest urban indoor gardens in the world,[257] located on the top floor of the Core Centre. Directly south of the city's downtown is the Beltline, an urban community known for its bars, nightclubs, restaurants, and shopping venues. At the Beltline's core is 17 Avenue SW, the community's primary entertainment and nightlife strip, lined with a high concentration of bars and entertainment. During the Calgary Flames' Stanley Cup run in 2004, 17 Avenue SW was frequented by over 50,000 fans and supporters per game night. The concentration of red jersey-wearing fans led to the street's playoff moniker, the "Red Mile". Downtown Calgary is easily accessed using the CTrain transit system with 9 train stations in the city's downtown core. The train is also fare-free while downtown.

Attractions in other areas of the city include the Heritage Park Historical Village, depicting life in pre-1914 Alberta and featuring working historic vehicles such as a steam train, paddle steamer and electric streetcar. The village itself comprises a mixture of replica buildings and historic structures relocated from southern Alberta. Just west of the city limits is Calaway Park, Western Canada's largest outdoor family amusement park, and just north of the park across the Trans Canada Highway is the YBV Springbank Airport, where the Wings over Springbank Airshow is held every July. Other major city attractions include Canada Olympic Park (which features Canada's Sports Hall of Fame) and Spruce Meadows. On top of the many shopping areas in the city centre, there are a number of large suburban shopping complexes in the city. Among the largest are Chinook Centre and Southcentre Mall in the south, Westhills and Signal Hill in the southwest, South Trail Crossing and Deerfoot Meadows in the southeast, Market Mall in the northwest, Sunridge Mall in the northeast, and the newly built CrossIron Mills and New Horizon Mall just north of the Calgary city limits, and south of the City of Airdrie.

Sports and recreation

[edit]

Within Calgary, there are approximately 8,000 ha (20,000 acres) of parkland available for public usage and recreation.[258] These parks include Fish Creek Provincial Park, Inglewood Bird Sanctuary, Bowness Park, Edworthy Park, Confederation Park, Prince's Island Park, Nose Hill Park, and Central Memorial Park. Nose Hill Park is one of the largest municipal parks in Canada at 1,129 ha (2,790 acres). The park has been subject to a revitalization plan that began in 2006. Its trail system is currently undergoing rehabilitation in accordance with this plan.[259][260] The oldest park in Calgary, Central Memorial Park, dates back to 1911. Similar to Nose Hill Park, revitalization also took place in Central Memorial Park in 2008–2009 and reopened to the public in 2010 while still maintaining its Victorian style.[261] An 800 km (500 mi) pathway system connects these parks and various neighbourhoods.[258][262] Calgary also has multiple private sporting clubs including the Glencoe Club and the Calgary Winter Club.