Agonal respiration

| Agonal respiration | |

|---|---|

| |

| Medical personnel performing chest compressions as part of ACLS | |

| Treatment | Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation |

Agonal respiration, gasping respiration, or agonal breathing is a distinct and abnormal pattern of breathing and brainstem reflex characterized by gasping labored breathing and is accompanied by strange vocalizations and myoclonus. Possible causes include cerebral ischemia, hypoxia (inadequate oxygen supply to tissue), or anoxia (total oxygen depletion). Agonal breathing is a severe medical sign requiring immediate medical attention, as the condition generally progresses to complete apnea and preludes death. The duration of agonal respiration can range from two breaths to several hours of labored breathing.[1]

The term is sometimes inaccurately used to refer to labored, gasping breathing patterns accompanying organ failure, systemic inflammatory response syndrome, septic shock, and metabolic acidosis.

Notably, end-of-life inability to tolerate secretions, known as the death rattle, is a separate phenomenon.[2][3]

Etymology

[edit]Agonal stems from the word agony, which denotes a struggle. As such, the word agonal is used exclusively in medicine to denote the physiologic dynamics of a person just prior to or at the time of death.[4]

Epidemiology

[edit]Agonal respiration occurs in 40% of cardiac arrests experienced outside a hospital environment. Patients with cardiac arrests due to problems with the heart were more likely to experience agonal respirations compared to cardiac arrests from a different cause. Patients with agonal respirations due to cardiac arrest are more likely to be discharged home from a hospital alive compared to those who do not experience agonal respirations during cardiac arrest.[5]

Etiology

[edit]Agonal respirations are commonly seen in cases of cardiogenic shock (decreased organ perfusion due to heart failure) or cardiac arrest (failure of heartbeat), where agonal respirations may persist for several minutes after cessation of heartbeat.[1][6][5] In an unresponsive, pulseless patient in cardiac arrest, agonal respirations are not effective breaths and are signs of cardiovascular and respiratory system failure.

Physiology

[edit]

Breathing is controlled via the respiratory center within the medulla oblongata, which sits at the lowest point of the brainstem. Therefore, agonal breathing confirms brainstem activity, a promising sign. [7] Additionally, it is thought that the gasping of air is due to a reflex within the brain stem, likely due to low oxygen concentrations within the blood.[1] The respiration is insufficient for the continuation of life as the patient is now at a cardiovascular and respiratory system compromise.[8]

Clinical features

[edit]Signs

[edit]

Agonal respirations are labored breathing and increased work of breathing that can be described as gasping and irregular in pattern. Often, the breathing coincides with high mortality conditions such as cardiac arrest and cardiogenic shock.

Management

[edit]This breathing indicates an emergency and should initiate CPR (cardiopulmonary resuscitation), including chest compressions, BLS (Basic Life Support), and a call to EMS (Emergency Medical Services).[8] Once the patient is in the care of healthcare professionals, the ACLS protocol may begin in order to achieve ROSC (return of spontaneous circulation), correct arrhythmias, and stabilize the patient.[9]

Prognosis

[edit]The outlook for patients following cardiac arrest and cardiogenic shock relies upon factors such as the cause of the arrest, time without a pulse, response to and quality of CPR, and other health ailments of the patient.[10]

Preserving brainstem activity with agonal breathing correlates with better neurological outcomes for patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.[7] The presence of agonal respirations in these cases indicates a more favorable prognosis than in cases of cardiac arrest without agonal respirations.[5]

Related patterns

[edit]Death rattle

[edit]

Throughout the dying process, patients will lose the ability to tolerate their secretions, resulting in a sound often disturbing and emotionally distressing to visitors termed the death rattle.[2] However, the death rattle is a separate phenomenon from agonal respirations specifically related to the patient's inability to tolerate their secretions.

For patients in the process of dying, without desire for resuscitation efforts ( do not resuscitate & do not intubate), managing oral and bronchial secretions (to reduce the sound of the death rattle) with anti-cholinergic medications and decreased fluid hydration may be beneficial in lowering distress upon family and visitors and patient symptoms; however, it will not have an impact on patient outcomes.[2][3]

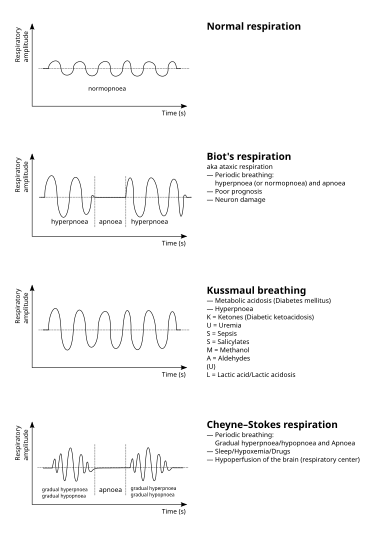

Kussmaul breathing

[edit]Respirations characterized by tachypnea and deep breathing to compensate for metabolic acidosis, such as in DKA.[11][12] This pattern of breathing coincides with respiratory failure. Intubation and mechanical ventilation are necessary.[12]

Cheyne Stokes respirations

[edit]A pattern of breathing during non-REM sleep is closely associated with left heart failure and characterized by intermittent periods of apnea and gradual increase and subsequent decrease in respiratory effort.[13][14] Patients will often have signs and symptoms of heart failure, such as difficulty breathing when lying flat and sleepiness during the daytime. Notably, this is not an end-of-life breathing pattern, and managing a patient's heart failure is first-line.[14]

Ataxic respirations

[edit]Also known as Biot's respirations, it is a form of breathing associated with neurological injury. It is characterized by irregular normal breathing patterns, apnea, and tachypnea.[15][16] Named after French physician Camille Biot, the breathing style differs from Cheyne Stokes in that the typical crescendo-decrescendo pattern is absent.[16] The frequency and authenticity of these respirations is debated, however with advancements in medicine, those who would experience these respirations would likely be on mechanical ventilation beforehand.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Perkin, RM; Resnik, DB (June 2002). "The agony of agonal respiration: is the last gasp necessary?". Journal of Medical Ethics. 28 (3): 164–9. doi:10.1136/jme.28.3.164. PMC 1733591. PMID 12042401.

- ^ a b c Shimizu, Yoichi (July 2014). "Care Strategy for Death Rattle in Terminally Ill Cancer Patients and Their Family Members: Recommendations From a Cross-Sectional Nationwide Survey of Bereaved Family Members' Perceptions". Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 48 (1): 2–12. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.07.010. PMID 24161372.

- ^ a b Wildiers, Hans; Menten, Johan (April 2002). "Death Rattle". Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 23 (4): 310–317. doi:10.1016/S0885-3924(01)00421-3. PMID 11997200.

- ^ Haubrich, William (2003). Medical Meanings: A Glossary of Word Origins (2nd ed.). American College of Physicians. p. 7.

- ^ a b c Clark, Jill J; Larsen, Mary Pat; Culley, Linda L; Graves, Judith Reid; Eisenberg, Mickey S (December 1992). "Incidence of agonal respirations in sudden cardiac arrest". Annals of Emergency Medicine. 21 (12): 1464–1467. doi:10.1016/S0196-0644(05)80062-9. PMID 1443844. Retrieved 21 February 2015.

- ^ Islam, Sumaiya A.; Lussier, Alexandre A.; Kobor, Michael S. (2018-01-01), Huitinga, Ingeborg; Webster, Maree J. (eds.), "Chapter 17 - Epigenetic analysis of human postmortem brain tissue", Handbook of Clinical Neurology, Brain Banking, 150, Elsevier: 237–261, doi:10.1016/b978-0-444-63639-3.00017-7, ISBN 9780444636393, PMID 29496144, retrieved 2020-12-11

- ^ a b Kitano, Shinnosuke; Suzuki, Kensuke; Tanaka, Chie; Kuno, Masamune; Kitamura, Nobuya; Yasunaga, Hideo; Aso, Shotaro; Tagami, Takashi (June 2024). "Agonal breathing upon hospital arrival as a prognostic factor in patients experiencing out-of-hospital cardiac arrest". Resuscitation Plus. 18: 100660. doi:10.1016/j.resplu.2024.100660. PMC 11109003. PMID 38778802.

- ^ a b Whited, Lacey; Hashmi, Muhammad F.; Graham, Derrel D. (2024), "Abnormal Respirations", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 29262235, retrieved 2024-10-30

- ^ "Algorithms". cpr.heart.org. Retrieved 2024-11-10.

- ^ Nickson, Chris (2019-01-08). "Prognosis After Cardiac Arrest". Life in the Fast Lane • LITFL. Retrieved 2024-11-19.

- ^ "Metabolic Acidosis in Emergency Medicine: Practice Essentials, Pathophysiology, Prognosis". 2024-10-29.

- ^ a b Moraes, Alice Gallo de; Surani, Salim (2019-01-15). "Effects of diabetic ketoacidosis in the respiratory system". World Journal of Diabetes. 10 (1): 16–22. doi:10.4239/wjd.v10.i1.16. ISSN 1948-9358. PMC 6347653. PMID 30697367.

- ^ Mared, Lena; Cline, Charles; Erhardt, Leif; Berg, Søren; Midgren, Bengt (2004-09-20). "Cheyne-Stokes respiration in patients hospitalised for heart failure". Respiratory Research. 5 (1): 14. doi:10.1186/1465-9921-5-14. ISSN 1465-993X. PMC 521193. PMID 15380031.

- ^ a b Naughton, M T (1998-06-01). "Pathophysiology and treatment of Cheyne-Stokes respiration". Thorax. 53 (6): 514–518. doi:10.1136/thx.53.6.514. ISSN 0040-6376. PMC 1745239. PMID 9713454.

- ^ Wijdicks, E. F M (2006-10-20). "Biot's breathing". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 78 (5): 512–513. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2006.104919. ISSN 0022-3050. PMC 2117832. PMID 17435185.

- ^ a b Summ, Oliver; Hassanpour, Nahid; Mathys, Christian; Groß, Martin (2022-06-01). "Disordered breathing in severe cerebral illness – Towards a conceptual framework". Respiratory Physiology & Neurobiology. 300: 103869. doi:10.1016/j.resp.2022.103869. ISSN 1569-9048. PMID 35181538.

External links

[edit]- "Incidence of Agonal Respirations in Sudden Cardiac Arrest". EMD Program. King County, Washington. 30 August 2003. Archived from the original on 10 February 2005. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- Bång, Angela; Herlitz, Johan; Martinell, Sven (2003). "Interaction between emergency medical dispatcher and caller in suspected out-of-hospital cardiac arrest calls with focus on agonal breathing. A review of 100 tape recordings of true cardiac arrest cases". Resuscitation. 56 (1): 25–34. doi:10.1016/S0300-9572(02)00278-2. PMID 12505735.

- Hazinski, Mary Fran, ed. (2011). BLS for healthcare providers (New ed.). Dallas, Tex.: American Heart Association. ISBN 978-1616690397.

- Gasping, even the dead breathe Real footage of a person with cardiac arrest and terminal breathing (gasping)