Gabapentin

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Neurontin, others[1] |

| Other names | CI-945; GOE-3450; DM-1796 (Gralise) |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a694007 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Dependence liability | Physical: High[3] Psychological: Moderate |

| Addiction liability | Low[4] |

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| Drug class | Gabapentinoid |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 27–60% (inversely proportional to dose; a high-fat meal also increases bioavailability)[8][9] |

| Protein binding | Less than 3%[8][9] |

| Metabolism | Not significantly metabolized[8][9] |

| Elimination half-life | 5 to 7 hours[8][9] |

| Excretion | Kidney[8][9] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| PDB ligand | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.056.415 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C9H17NO2 |

| Molar mass | 171.240 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Gabapentin, sold under the brand name Neurontin among others, is an anticonvulsant medication primarily used to treat neuropathic pain and also for partial seizures[10][7] of epilepsy. It is a commonly used medication for the treatment of neuropathic pain caused by diabetic neuropathy, postherpetic neuralgia, and central pain.[11] It is moderately effective: about 30–40% of those given gabapentin for diabetic neuropathy or postherpetic neuralgia have a meaningful benefit.[12]

Gabapentin, like other gabapentinoid drugs, acts by decreasing activity of the α2δ-1 protein, coded by the CACNA2D1 gene, first known as an auxiliary subunit of voltage gated calcium channels.[13][14][15] However, see Pharmacodynamics, below. By binding to α2δ-1, gabapentin reduces the release of excitatory neurotransmitters (primarily glutamate) and as a result, reduces excess excitation of neuronal networks in the spinal cord and brain. Sleepiness and dizziness are the most common side effects. Serious side effects include respiratory depression, and allergic reactions.[7] As with all other antiepileptic drugs approved by the FDA, gabapentin is labeled for an increased risk of suicide. Lower doses are recommended in those with kidney disease.[7]

Gabapentin was first approved for use in the United Kingdom in 1993.[16] It has been available as a generic medication in the United States since 2004.[17] It is the first of several other drugs that are similar in structure and mechanism, called gabapentinoids. In 2022, it was the tenth most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 40 million prescriptions.[18][19] During the 1990s, Parke-Davis, a subsidiary of Pfizer, used a number of illegal techniques to encourage physicians in the United States to prescribe gabapentin for unapproved uses.[20] They have paid out millions of dollars to settle lawsuits regarding these activities.[21]

Medical uses

[edit]Gabapentin is recommended for use in focal seizures and neuropathic pain.[7][10] Gabapentin is prescribed off-label in the US and the UK,[22][23] for example, for the treatment of non-neuropathic pain,[22] anxiety disorders, sleep problems and bipolar disorder.[24] In recent years, gabapentin has seen increased use, particularly in the elderly.[25] There is concern regarding gabapentin's off-label use due to the lack of strong scientific evidence for its efficacy in multiple conditions, its proven side effects and its potential for misuse and physical/psychological dependency.[26][27][28]

Seizures

[edit]Gabapentin is approved for the treatment of focal seizures;[29] however, it is not effective for generalized epilepsy.[30]

Neuropathic pain

[edit]Gabapentin is recommended as a first-line treatment for chronic neuropathic pain by various medical authorities.[10][11][31][32] This is a general recommendation applicable to all neuropathic pain syndromes except for trigeminal neuralgia, where it may be used as a second- or third-line agent.[11][32]

Regarding the specific diagnoses, a systematic review has found evidence for gabapentin to provide pain relief for some people with postherpetic neuralgia and diabetic neuropathy.[12] Gabapentin is approved for the former indication in the US.[7] In addition to these two neuropathies, European Federation of Neurological Societies guideline notes gabapentin effectiveness for central pain.[11] A combination of gabapentin with an opioid or nortriptyline may work better than either drug alone.[11][32]

Gabapentin shows substantial benefit (at least 50% pain relief or a patient global impression of change (PGIC) "very much improved") for neuropathic pain (postherpetic neuralgia or peripheral diabetic neuropathy) in 30–40% of subjects treated as compared to those treated with placebo.[12]

Evidence finds little or no benefit and significant risk in those with chronic low back pain or sciatica.[33][34] Gabapentin is not effective in HIV-associated sensory neuropathy[35] and neuropathic pain due to cancer.[36]

Anxiety

[edit]There is a small amount of research on the use of gabapentin for the treatment of anxiety disorders.[37][38]

Gabapentin is effective for the long-term treatment of social anxiety disorder and in reducing preoperative anxiety.[26][27]

In a controlled trial of breast cancer survivors with anxiety,[38] and a trial for social phobia,[37] gabapentin significantly reduced anxiety levels.

For panic disorder, gabapentin has produced mixed results.[38][37][27]

Sleep

[edit]Gabapentin is effective in treating sleep disorders such as insomnia and restless legs syndrome that are the result of an underlying illness, but comes with some risk of discontinuation and withdrawal symptoms after prolonged use at higher doses.[39]

Gabapentin enhances slow-wave sleep in people with primary insomnia. It also improves sleep quality by elevating sleep efficiency and decreasing spontaneous arousal.[40]

Drug dependence

[edit]Gabapentin is moderately effective in reducing the symptoms of alcohol withdrawal and associated craving.[41][42][43] The evidence in favor of gabapentin is weak in the treatment of alcoholism: it does not contribute to the achievement of abstinence, and the data on the relapse of heavy drinking and percent of days abstinent do not robustly favor gabapentin; it only decreases the percent days of heavy drinking.[44]

Gabapentin is ineffective in cocaine dependence and methamphetamine use,[45] and it does not increase the rate of smoking cessation.[46] While some studies indicate that gabapentin does not significantly reduce the symptoms of opiate withdrawal, there is increasing evidence that gabapentinoids are effective in controlling some of the symptoms during opiate detoxification. A clinical study in Iran, where heroin dependence is a significant social and public health problem, showed gabapentin produced positive results during an inpatient therapy program, particularly by reducing opioid-induced hyperalgesia and drug craving.[47][45] There is insufficient evidence for its use in cannabis dependence.[48]

Other

[edit]Gabapentin is recommended as a first-line treatment of the acquired pendular nystagmus, torsional nystagmus, and infantile nystagmus; however, it does not work in periodic alternating nystagmus.[49][50][51]

Gabapentin decreases the frequency of hot flashes in both menopausal women and people with breast cancer. However, antidepressants have similar efficacy, and treatment with estrogen more effectively prevents hot flashes.[52]

Gabapentin reduces spasticity in multiple sclerosis and is prescribed as one of the first-line options.[53] It is an established treatment of restless legs syndrome.[54] Gabapentin alleviates itching in kidney failure (uremic pruritus)[55][56] and itching of other causes.[57] It may be an option in essential or orthostatic tremor.[58][59][60]

Gabapentin does not appear to provide benefit for bipolar disorder,[27][42][61] complex regional pain syndrome,[62] post-surgical pain,[63] or tinnitus,[64] or prevent episodic migraine in adults.[65]

Contraindications

[edit]Gabapentin should be used carefully and at lower doses in people with kidney problems due to possible accumulation and toxicity. It is unclear if it is safe during pregnancy or breastfeeding.[7]

Side effects

[edit]

Dizziness and somnolence are the most frequent side effects.[7] Fatigue, ataxia, peripheral edema (swelling of extremities), and nystagmus are also common.[7] A 2017 meta-analysis found that gabapentin also increased the risk of difficulties in mentation and visual disturbances as compared to a placebo.[66] Gabapentin is associated with a weight gain of 2.2 kg (4.9 lb) after 1.5 months of use.[67] Case studies indicate that it may cause anorgasmia and erectile dysfunction,[68] as well as myoclonus[69][70] that disappear after discontinuing gabapentin or replacing it with other medication. Fever, swollen glands that do not go away, eyes or skin turning yellow, unusual bruises or bleeding, unexpected muscle pain or weakness, rash, long-lasting stomach pain which may indicate an inflamed pancreas, hallucinations, anaphylaxis, respiratory depression, and increased suicidal ideation are rare but serious side effects.[71]

Suicide

[edit]As with all antiepileptic drugs approved in the US, gabapentin label contains a warning of an increased risk of suicidal thoughts and behaviors.[7] This warning is based on a meta-analysis of all approved antiepileptic drugs in 2008, and not with gabapentin alone.[72] According to an experimental meta-analysis of insurance claims database, gabapentin use is associated with about 40% increased risk of suicide, suicide attempt and violent death as compared with a reference anticonvulsant drug topiramate. The risk is increased for people with bipolar disorder or epilepsy.[72] Another study has shown an approximately doubled rate of suicide attempts and self-harm in people with bipolar disorder who are taking gabapentin versus those taking lithium.[73] A large Swedish study suggests that gabapentinoids are associated with an increased risk of suicidal behaviour, unintentional overdoses, head/body injuries, and road traffic incidents and offences.[74] On the other hand, a study published by the Harvard Data Science Review found that gabapentin was associated with a significantly reduced rate of suicide.[75]

Respiratory depression

[edit]Serious breathing suppression, potentially fatal, may occur when gabapentin is taken together with opioids, benzodiazepines, or other depressants, or by people with underlying lung problems such as COPD.[76] Gabapentin and opioids are commonly prescribed or abused together, and research indicates that the breathing suppression they cause is additive. For example, gabapentin use before joint replacement or laparoscopic surgery increased the risk of respiratory depression by 30–60%.[76] A Canadian study showed that use of gabapentin and other gabapentinoids, whether for epilepsy, neuropathic pain or other chronic pain was associated with a 35–58% increased risk for severe exacerbation of pre-existing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.[77]

Withdrawal and dependence

[edit]Withdrawal symptoms typically occur 1–2 days after abruptly stopping gabapentin (almost unambiguously due to extended use and during a very short-term rebound phenomenon) — similar to, albeit less intense than most benzodiazepines.[78] Agitation, confusion and disorientation are the most frequently reported, followed by gastrointestinal complaints and sweating, and more rare tremor, tachycardia, hypertension and insomnia.[78] In some cases, users experience withdrawal seizures after chronic or semi-chronic use in the absence of periodic cycles or breaks during repeating and consecutive use.[79] All these symptoms subside when gabapentin is re-instated[78] or tapered off gradually at an appropriate rate.[citation needed]

On its own, gabapentin appears to not have a substantial addictive power. In human and animal experiments, it shows limited to no rewarding effects. The vast majority of people abusing gabapentin are current or former abusers of opioids or sedatives.[79] In these persons, gabapentin can boost the opioid "high" as well as decrease commonly experienced opioid-withdrawal symptoms such as anxiety.[80]

Overdose

[edit]Through excessive ingestion, accidental or otherwise, persons may experience overdose symptoms including drowsiness, sedation, blurred vision, slurred speech, somnolence, uncontrollable jerking motions, and anxiety. A very high amount taken is associated with breathing suppression, coma, and possibly death, particularly if combined with alcohol or opioids.[79][81]

Pharmacology

[edit]Animal Models

[edit]Gabapentin, prevents seizures in a dose-related manner in several laboratory animal models.[82] These models include spinal extensor seizures from low-intensity electroshock to the forebrain in mice, maximal electroshock in rats, spinal extensor seizures in DBA/2 mice with a genetic sensitivity to seizures induced by loud noise, and in rats "kindled" to produce focal seizures by repeated prior electrical stimulation of the hippocampus. Gabapentin slightly increased spontaneous absence-like seizures in a genetically susceptible strain recorded with electroencephalography. All of these effects of gabapentin were seen at dosages at or below the threshold for producing ataxia.

Gabapentin also has been tested in a wide variety of animal models that are relevant for analgesic actions.[83] Generally, gabapentin is not active to prevent pain-related behaviors in models of acute nociceptive pain, but it prevents pain-related behaviors when animals are made sensitive by prior peripheral inflammation or peripheral nerve damage (inflammatory or neuropathic conditions).

Pharmacodynamics

[edit]Gabapentin is a ligand of the α2δ calcium channel subunit.[84][85] The α2δ-1 protein is coded by the CACNA2D1 gene. α2δ was first described as an auxiliary protein connected to the main α1 subunit (the channel-forming protein) of high voltage activated voltage-dependent calcium channels (L-type, N-type, P/Q type, and R-type).[13] The same α2δ protein has more recently been shown to interact directly with some NMDA-type and AMPA-type glutamate receptors at presynaptic sites and also with thrombospondin (an extracellular matrix protein secreted by astroglial cells).[86]

Gabapentin is not a direct calcium channel blocker: it exerts its actions by disrupting the regulatory function of α2δ and its interactions with other proteins. Gabapentin reduces delivery of intracellular calcium channels to the cell membrane, reduces the activation of the channels by the α2δ subunit, decreases signaling leading to neurotransmitters release, and disrupts interactions of α2δ with voltage gated calcium channels but also with NMDA receptors, neurexins, and thrombospondin.[13][14][15] These proteins are found as mutually interacting parts of the presynaptic active zone, where numerous protein molecules interact with each other to enable and to regulate the release of neurotransmitters from presynaptic vesicles into the synaptic space.

Out of the four known isoforms of α2δ protein, gabapentin binds with similar high affinity to two: α2δ-1 and α2δ-2.[85] All of the pharmacological properties of gabapentin tested to date are explained by its binding to just one isoform – α2δ-1.[85][14]

The endogenous α-amino acids L-leucine and L-isoleucine, which resemble gabapentin in chemical structure, bind α2δ with similar affinity to gabapentin and are present in human cerebrospinal fluid at micromolar concentrations.[87] They may be the endogenous ligands of the α2δ subunit, and they competitively antagonize the effects of gabapentin.[87][88] Accordingly, while gabapentin has nanomolar affinity for the α2δ subunit, its potency in vivo is in the low micromolar range, and competition for binding by endogenous L-amino acids is likely to be responsible for this discrepancy.[14]

Gabapentin is a potent activator of voltage-gated potassium channels KCNQ3 and KCNQ5, even at low nanomolar concentrations. However, this activation is unlikely to be the dominant mechanism of gabapentin's therapeutic effects.[89]

Gabapentin is structurally similar to the neurotransmitter glutamate and competitively inhibits branched-chain amino acid aminotransferase (BCAT), slowing down the synthesis of glutamate.[90] In particular, it inhibits BCAT-1 at high concentrations (Ki = 1 mM), but not BCAT-2.[91] At very high concentrations gabapentin can suppress the growth of cancer cells, presumably by affecting mitochondrial catabolism, however, the precise mechanism remains elusive.[91]

Even though gabapentin is a structural GABA analogue, and despite its name, it does not bind to the GABA receptors, does not convert into GABA or another GABA receptor agonist in vivo, and does not modulate GABA transport or metabolism within the range of clinical dosing.[84] In vitro gabapentin has been found to very weakly inhibit the GABA aminotransferase enzyme (Ki = 17–20 mM), however, this effect is so weak it is not clinically relevant at prescribed doses.[90]

Pharmacokinetics

[edit]Gabapentin is absorbed from the intestines by an active transport process mediated via an amino acid transporter, presumably, LAT2.[92] As a result, the pharmacokinetics of gabapentin is dose-dependent, with diminished bioavailability and delayed peak levels at higher doses.[85]

The oral bioavailability of gabapentin is approximately 80% at 100 mg administered three times daily once every 8 hours, but decreases to 60% at 300 mg, 47% at 400 mg, 34% at 800 mg, 33% at 1,200 mg, and 27% at 1,600 mg, all with the same dosing schedule.[7][93] Drugs that increase the transit time of gabapentin in the small intestine can increase its oral bioavailability; when gabapentin was co-administered with oral morphine, the oral bioavailability of a 600 mg dose of gabapentin increased by 50%.[93]

Gabapentin at a low dose of 100 mg has a Tmax (time to peak levels) of approximately 1.7 hours, while the Tmax increases to 3 to 4 hours at higher doses.[85] Food does not significantly affect the Tmax of gabapentin and increases the Cmax and area-under-curve levels of gabapentin by approximately 10%.[93]

Gabapentin can cross the blood–brain barrier and enter the central nervous system.[84] Gabapentin concentration in cerebrospinal fluid is approximately 9–14% of its blood plasma concentration.[93] Due to its low lipophilicity,[93] gabapentin requires active transport across the blood–brain barrier.[94][84][95][96] The LAT1 is highly expressed at the blood–brain barrier[97] and transports gabapentin across into the brain.[94][84][95][96] As with intestinal absorption mediated by an amino acid transporter, the transport of gabapentin across the blood–brain barrier by LAT1 is saturable.[94] Gabapentin does not bind to other drug transporters such as P-glycoprotein (ABCB1) or OCTN2 (SLC22A5).[94] It is not significantly bound to plasma proteins (<1%).[93]

Gabapentin undergoes little or no metabolism.[85][93]

Gabapentin is generally safe in people with liver cirrhosis.[98]

Gabapentin is eliminated renally in the urine.[93] It has a relatively short elimination half-life, with the reported average value of 5 to 7 hours.[93] Because of its short elimination half-life, gabapentin must be administered 3 to 4 times per day to maintain therapeutic levels.[99] Gabapentin XR (brand name Gralise) is taken once a day.[100]

Chemistry

[edit]

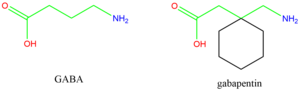

Gabapentin is a 3,3-disubstituted derivative of GABA. Therefore, it is a GABA analogue, as well as a γ-amino acid.[101][102] It is similar to several other compounds that collectively are called gabapentinoids. Specifically, it is a derivative of GABA with a pentyl disubstitution at 3 position, hence, the name - gabapentin, in such a way as to form a six-membered ring. After the formation of the ring, the amine and carboxylic groups are not in the same relative positions as they are in the GABA;[103] they are more conformationally constrained.[104]

Although it has been known for some time that gabapentin must bind to the α2δ-1 protein in order to act pharmacologically (see Pharmacodynamics), the three-dimensional structure of the α2δ-1 protein with gabapentin bound (or alternatively, the native amino acid, L-Isoleucine bound) has only recently been obtained by cryo-electron microscopy.[105] A figure of this drug-bound structure is shown in the Chemistry section of the entry on gabapentinoid drugs. This study confirms other findings to show that both compounds alternatively can bind at a single extracellular site (somewhat distant from the calcium conducting pore of the voltage gated calcium channel α1 subunit) on the calcium channel and chemotaxis (Cache1) domain of α2δ-1.

Synthesis

[edit]

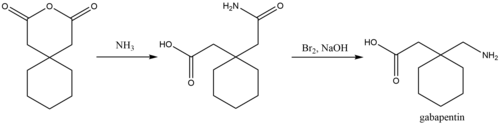

A process for chemical synthesis and isolation of gabapentin with high yield and purity[106] starts with conversion of 1,1-cyclohexanediacetic anhydride to 1,1-cyclohexanediacetic acid monoamide and is followed by a 'Hofmann' rearrangement in an aqueous solution of sodium hypobromite prepared in situ.

History

[edit]GABA is the principle inhibitory neurotransmitter in mammalian brain. By the early 1970s, it was appreciated that there are two main classes of GABA receptors, GABAA and GABAB and also that baclofen was an agonist of GABAB receptors. Gabapentin was designed, synthesized and tested in mice by researchers at the pharmaceutical company Goedecke AG in Freiburg, Germany (a subsidiary of Parke-Davis). It was meant to be an analogue of the neurotransmitter GABA that could more easily cross the blood–brain barrier. It was first synthesized in 1974/75 and described in 1975[107] by Satzinger and Hartenstein.[103][108]

The first pharmacology findings published were sedating properties and prevention of seizures in mice evoked by the GABA antagonist, thiosemicarbazide.[107] Shortly after, gabapentin was shown in vitro to reduce the release of the neurotransmitter dopamine from slices of rat caudate nucleus (striatum).[109] This study provided evidence that the action of gabapentin, unlike baclofen, did not arise from the GABAB receptor. Subsequently, more than 2,000 scientific papers have been published that contain the words "gabapentin pharmacology" or "pharmacology of gabapentin" (Google Scholar citation search).

Initial clinical trials utilizing small numbers of subjects were for treatment of spasticity[110] and migraine[111] but neither study had statistical power to allow conclusions. In 1987, the first positive results with gabapentin were obtained in a clinical trial using three dose groups versus pre-treatment seizure frequency for 75 days, as add-on treatment in patients who still had seizures despite taking other medications.[112] This study did not show statistically significant results, but it did show a strong dose-related trend to decreased frequency of seizures.

Under the brand name Neurontin, it was first approved in the United Kingdom in May 1993, for the treatment of refractory epilepsy.[113] Approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration followed in December 1993, also for use as an adjuvant (effective when added to other antiseizure drugs) medication to control partial seizures in adults; that indication was extended to children in 2000.[114][7] Subsequently, gabapentin was approved in the United States for the treatment of pain from postherpetic neuralgia in 2002.[115] A generic version of gabapentin first became available in the United States in 2004.[17] An extended-release formulation of gabapentin for once-daily administration, under the brand name Gralise, was approved in the United States for the treatment of postherpetic neuralgia in January 2011.[116][117]

In recent years, gabapentin has been prescribed for an increasing range of disorders and is one of the more common medications used, particularly in elderly people.[118]

Society and culture

[edit]Legal status

[edit]United Kingdom

[edit]Effective April 2019, the United Kingdom reclassified the drug as a class C controlled substance.[119][120][121][122][123]

United States

[edit]Gabapentin is not a controlled substance under the federal Controlled Substances Act.[124] Effective 1 July 2017, Kentucky classified gabapentin as a schedule V controlled substance statewide.[125] Gabapentin is scheduled V drug in other states such as West Virginia,[126] Tennessee,[127] Alabama,[128] Utah,[129] and Virginia.[130]

Off-label promotion

[edit]Although some small, non-controlled studies in the 1990s—mostly sponsored by gabapentin's manufacturer—suggested that treatment for bipolar disorder with gabapentin may be promising,[131] the preponderance of evidence suggests that it is not effective.[132]

Franklin v. Parke-Davis case

[edit]

After the corporate acquisition of the original patent holder, the pharmaceutical company Pfizer admitted that there had been violations of FDA guidelines regarding the promotion of unproven off-label uses for gabapentin in the Franklin v. Parke-Davis case.

While off-label prescriptions are common for many drugs, marketing of off-label uses of a drug is not.[20] In 2004, Warner-Lambert (which subsequently was acquired by Pfizer) agreed to plead guilty for activities of its Parke-Davis subsidiary, and to pay $430 million in fines to settle civil and criminal charges regarding the marketing of Neurontin for off-label purposes. The 2004 settlement was one of the largest in U.S. history up to that point, and the first off-label promotion case brought successfully under the False Claims Act.[133]

Kaiser Foundation Hospitals and Kaiser Foundation Health Plan sued Pfizer Inc., alleging that the pharmaceutical company had misled Kaiser by recommending Neurontin as an off-label treatment for certain conditions (including bipolar disorder, migraines, and neuropathic pain).[134][135][136] In 2010, a federal jury in Massachusetts ruled in Kaiser's favor, finding that Pfizer violated the federal Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) Act and was liable for US$47.36 million in damages, which was automatically trebled to just under $142.1 million.[135][134] Aetna, Inc. and a group of employer health plans prevailed in their similar Neurontin-related claims against Pfizer.[137] Pfizer appealed, but the U.S. Court of Appeals for the First Circuit upheld the verdict,[137] and in 2013, the US Supreme Court declined to hear the case.[138][139]

Gabasync

[edit]Gabasync, a treatment consisting of a combination of gabapentin and two other medications (flumazenil and hydroxyzine) as well as therapy, is an ineffective treatment promoted for methamphetamine addiction, though it had also been claimed to be effective for dependence on alcohol or cocaine.[140] It was marketed as PROMETA. While the individual drugs had been approved by the FDA, their off-label use for addiction treatment has not.[141] Gabasync was marketed by Hythiam, Inc. which is owned by Terren Peizer, a former junk bond salesman who has since been indicted for securities fraud relative to another company.[142][140] Hythiam charges up to $15,000 per patient to license its use (of which half goes to the prescribing physician, and half to Hythiam).[143]

In November 2011, the results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled study (financed by Hythiam and carried out at UCLA) were published in the peer-reviewed journal Addiction. It concluded that Gabasync is ineffective: "The PROMETA protocol, consisting of flumazenil, gabapentin and hydroxyzine, appears to be no more effective than placebo in reducing methamphetamine use, retaining patients in treatment or reducing methamphetamine craving."[144]

Barrons, in a November 2005 article entitled "Curb Your Cravings For This Stock", wrote "If the venture works out for patients and the investing public, it'll be a rare success for Peizer, who's promoted a series of disappointing small-cap medical or technology stocks ... since his days at Drexel".[145] Journalist Scott Pelley said to Peizer in 2007: "Depending and who you talk to, you're either a revolutionary or a snake oil salesman."[146][145] 60 Minutes, NBC News, and The Dallas Morning News criticized Peizer after the company bypassed clinical studies and government approval when bringing to market Prometa; the addiction drug proved to be completely ineffective.[147][148][140][149] Journalist Adam Feuerstein opined: "most of what Peizer says is dubious-sounding hype".[150]

Usage trends

[edit]The period from 2008 to 2018 saw a significant increase in the consumption of gabapentinoids. A study published in Nature Communications in 2023 highlights this trend, demonstrating a notable escalation in sales of gabapentinoids. The study, which analyzed healthcare data across 65 countries/ regions, found that the consumption rate of gabapentinoids had doubled over the decade, driven by their use in a wide range of indications.[151]

Brand names

[edit]Gabapentin was originally marketed under the brand name Neurontin. Since it became generic, it has been marketed worldwide using over 300 different brand names.[1] An extended-release formulation of gabapentin for once-daily administration was introduced in 2011, for postherpetic neuralgia under the brand name Gralise.[152]

In the US, Neurontin is marketed by Viatris after Upjohn was spun off from Pfizer.[153][154][155]

Related drugs

[edit]Parke-Davis developed a drug called pregabalin, which is related in structure to gabapentin, as a successor to gabapentin.[156] Another similar drug atagabalin has been unsuccessfully tried by Pfizer as a treatment for insomnia.[157] A prodrug form (gabapentin enacarbil)[158] was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Recreational use

[edit]The examples and perspective in this section deal primarily with US and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (August 2024) |

When taken in excess, gabapentin can induce euphoria, a sense of calm, a cannabis-like high, improved sociability, and reduced alcohol or cocaine cravings.[159][160][161] Also known on the streets as "Gabbies",[162] gabapentin was reported in 2017 to be increasingly abused and misused for these euphoric effects.[163][164] About 1 percent of the responders to an Internet poll and 22 percent of those attending addiction facilities had a history of abuse of gabapentin.[78][165] Gabapentin misuse, toxicity, and use in suicide attempts among adults in the US increased from 2013 to 2017.[166]

After Kentucky implemented stricter legislation regarding opioid prescriptions in 2012, there was an increase in gabapentin-only and multi-drug use from 2012 to 2015. The majority of these cases were from overdose in suspected suicide attempts. These rates were also accompanied by increases in abuse and recreational use.[167]

Withdrawal symptoms, often resembling those of benzodiazepine withdrawal, play a role in the physical dependence some users experience.[79] Its misuse predominantly coincides with the usage of other CNS depressant drugs, namely opioids, benzodiazepines, and alcohol.[168]

Veterinary use

[edit]In cats, gabapentin can be used as an analgesic in multi-modal pain management,[169] anxiety medication to reduce stress during travel or vet visits,[170] and anticonvulsant.[171]

Veterinarians may prescribe gabapentin as an anticonvulsant and pain reliever in dogs.[172][171] It has beneficial effects for treating epilepsy, different kinds of pain (chronic, neuropathic, and post-operative pain), and anxiety, lip-licking behaviour, storm phobia, fear-based aggression.[173][174]

It is also used to treat chronic pain-associated nerve inflammation in horses and dogs. Side effects include tiredness and loss of coordination, but these effects generally go away within 24 hours of starting the medication.[172][171]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "International listings for Gabapentin". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 16 February 2016. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ "Gabapentin Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. 2 December 2019. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- ^ Tran KT, Hranicky D, Lark T, Jacob NJ (June 2005). "Gabapentin withdrawal syndrome in the presence of a taper". Bipolar Disorders. 7 (3): 302–4. doi:10.1111/j.1399-5618.2005.00200.x. PMID 15898970.

- ^ Schifano F (June 2014). "Misuse and abuse of pregabalin and gabapentin: cause for concern?". CNS Drugs. 28 (6): 491–496. doi:10.1007/s40263-014-0164-4. PMID 24760436.

- ^ "Prescription medicines: registration of new generic medicines and biosimilar medicines, 2017". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). 21 June 2022. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ Anvisa (31 March 2023). "RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 4 April 2023). Archived from the original on 3 August 2023. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Neurontin- gabapentin capsule Neurontin- gabapentin tablet, film coated Neurontin- gabapentin solution". DailyMed. 11 April 2019. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- ^ a b c d e "Neurontin, Gralise (gabapentin) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Archived from the original on 16 December 2014. Retrieved 6 April 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Goa KL, Sorkin EM (September 1993). "Gabapentin. A review of its pharmacological properties and clinical potential in epilepsy". Drugs. 46 (3): 409–427. doi:10.2165/00003495-199346030-00007. PMID 7693432. S2CID 265753780.

- ^ a b c "1 Recommendations | Neuropathic pain in adults: pharmacological management in non-specialist settings | Guidance". National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). 20 November 2013. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Attal N, Cruccu G, Baron R, Haanpää M, Hansson P, Jensen TS, et al. (September 2010). "EFNS guidelines on the pharmacological treatment of neuropathic pain: 2010 revision". European Journal of Neurology. 17 (9): 1113–1e88. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.02999.x. PMID 20402746. S2CID 14236933.

- ^ a b c Wiffen PJ, Derry S, Bell RF, Rice AS, Tölle TR, Phillips T, et al. (June 2017). "Gabapentin for chronic neuropathic pain in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 6 (6): CD007938. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007938.pub4. hdl:10044/1/52908. PMC 6452908. PMID 28597471.

- ^ a b c Risher WC, Eroglu C (August 2020). "Emerging roles for α2δ subunits in calcium channel function and synaptic connectivity". Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 63: 162–169. doi:10.1016/j.conb.2020.04.007. PMC 7483897. PMID 32521436.

- ^ a b c d Stahl SM, Porreca F, Taylor CP, Cheung R, Thorpe AJ, Clair A (June 2013). "The diverse therapeutic actions of pregabalin: is a single mechanism responsible for several pharmacological activities?". Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 34 (6): 332–339. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2013.04.001. PMID 23642658.

- ^ a b Taylor CP, Harris EW (July 2020). "Analgesia with Gabapentin and Pregabalin May Involve N-Methyl-d-Aspartate Receptors, Neurexins, and Thrombospondins". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 374 (1): 161–174. doi:10.1124/jpet.120.266056. PMID 32321743. S2CID 216082872.

- ^ Pitkänen A, Schwartzkroin PA, Moshé SL (2005). Models of Seizures and Epilepsy. Burlington: Elsevier. p. 539. ISBN 978-0-08-045702-4. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ a b Reed D (2 March 2012). The Other End of the Stethoscope: The Physician's Perspective on the Health Care Crisis. AuthorHouse. pp. 63–. ISBN 978-1-4685-4410-7.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2022". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 30 August 2024. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ "Gabapentin Drug Usage Statistics, United States, 2013 - 2022". ClinCalc. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ a b Henney JE (August 2006). "Safeguarding patient welfare: who's in charge?". Annals of Internal Medicine. 145 (4): 305–307. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-145-4-200608150-00013. PMID 16908923. S2CID 39262014.

- ^ Stempel J (2 June 2014). "Pfizer to pay $325 million in Neurontin settlement". Reuters. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- ^ a b Montastruc F, Loo SY, Renoux C (November 2018). "Trends in First Gabapentin and Pregabalin Prescriptions in Primary Care in the United Kingdom, 1993-2017". JAMA. 320 (20): 2149–2151. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.12358. PMC 6583557. PMID 30480717.

- ^ Goodman CW, Brett AS (May 2019). "A Clinical Overview of Off-label Use of Gabapentinoid Drugs". JAMA Internal Medicine. 179 (5): 695–701. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0086. PMID 30907944. S2CID 85497732.

- ^ Sobel SV (5 November 2012). Successful Psychopharmacology: Evidence-Based Treatment Solutions for Achieving Remission. W. W. Norton. p. 124. ISBN 978-0-393-70857-8. Archived from the original on 6 January 2016.

- ^ Span P (17 August 2024). "The Painkiller Used for Just About Anything". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 January 2024.

- ^ a b "Review finds little evidence to support gabapentinoid use in bipolar disorder or insomnia". NIHR Evidence (Plain English summary). National Institute for Health and Care Research. 17 October 2022. doi:10.3310/nihrevidence_54173. S2CID 252983016.

- ^ a b c d Hong JS, Atkinson LZ, Al-Juffali N, Awad A, Geddes JR, Tunbridge EM, et al. (March 2022). "Gabapentin and pregabalin in bipolar disorder, anxiety states, and insomnia: Systematic review, meta-analysis, and rationale". Molecular Psychiatry. 27 (3): 1339–1349. doi:10.1038/s41380-021-01386-6. PMC 9095464. PMID 34819636.

- ^ Tran KT, Hranicky D, Lark T, Jacob NJ (June 2005). "Gabapentin withdrawal syndrome in the presence of a taper". Bipolar Disorders. 7 (3): 302–4. doi:10.1111/j.1399-5618.2005.00200.x. PMID 15898970.

- ^ Johannessen SI, Ben-Menachem E (2006). "Management of focal-onset seizures: an update on drug treatment". Drugs. 66 (13): 1701–1725. doi:10.2165/00003495-200666130-00004. PMID 16978035. S2CID 46952737.

- ^ Rheims S, Ryvlin P (July 2014). "Pharmacotherapy for tonic-clonic seizures". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 15 (10): 1417–1426. doi:10.1517/14656566.2014.915029. PMID 24798217. S2CID 6943460.

- ^ Moulin DE, Clark AJ, Gilron I, Ware MA, Watson CP, Sessle BJ, et al. (2007). "Pharmacological management of chronic neuropathic pain - consensus statement and guidelines from the Canadian Pain Society". Pain Research & Management. 12 (1): 13–21. doi:10.1155/2007/730785. PMC 2670721. PMID 17372630.

- ^ a b c Finnerup NB, Attal N, Haroutounian S, McNicol E, Baron R, Dworkin RH, et al. (February 2015). "Pharmacotherapy for neuropathic pain in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis". The Lancet. Neurology. 14 (2): 162–173. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70251-0. PMC 4493167. PMID 25575710.

- ^ Shanthanna H, Gilron I, Rajarathinam M, AlAmri R, Kamath S, Thabane L, et al. (August 2017). "Benefits and safety of gabapentinoids in chronic low back pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". PLOS Medicine. 14 (8): e1002369. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002369. PMC 5557428. PMID 28809936.

- ^ Enke O, New HA, New CH, Mathieson S, McLachlan AJ, Latimer J, et al. (July 2018). "Anticonvulsants in the treatment of low back pain and lumbar radicular pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis". CMAJ. 190 (26): E786 – E793. doi:10.1503/cmaj.171333. PMC 6028270. PMID 29970367.

- ^ Phillips TJ, Cherry CL, Cox S, Marshall SJ, Rice AS (December 2010). "Pharmacological treatment of painful HIV-associated sensory neuropathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials". PLOS ONE. 5 (12): e14433. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...514433P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0014433. PMC 3010990. PMID 21203440.

- ^ Moore A, Derry S, Wiffen P (February 2018). "Gabapentin for Chronic Neuropathic Pain". JAMA. 319 (8): 818–819. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.21547. PMID 29486015.

- ^ a b c Mula M, Pini S, Cassano GB (June 2007). "The role of anticonvulsant drugs in anxiety disorders: a critical review of the evidence". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 27 (3): 263–272. doi:10.1097/jcp.0b013e318059361a. PMID 17502773. S2CID 38188832.

- ^ a b c Greenblatt HK, Greenblatt DJ (March 2018). "Gabapentin and Pregabalin for the Treatment of Anxiety Disorders". Clinical Pharmacology in Drug Development. 7 (3): 228–232. doi:10.1002/cpdd.446. PMID 29579375. S2CID 4321472.

- ^ Liu GJ, Karim MR, Xu LL, Wang SL, Yang C, Ding L, et al. (2017). "Efficacy and Tolerability of Gabapentin in Adults with Sleep Disturbance in Medical Illness: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". Frontiers in Neurology. 8: 316. doi:10.3389/fneur.2017.00316. PMC 5510619. PMID 28769860.

- ^ Lo HS, Yang CM, Lo HG, Lee CY, Ting H, Tzang BS (2010). "Treatment effects of gabapentin for primary insomnia". Clinical Neuropharmacology. 33 (2): 84–90. doi:10.1097/WNF.0b013e3181cda242. PMID 20124884. S2CID 4046961.

- ^ Muncie HL, Yasinian Y, Oge' L (November 2013). "Outpatient management of alcohol withdrawal syndrome". American Family Physician. 88 (9): 589–595. PMID 24364635.

- ^ a b Berlin RK, Butler PM, Perloff MD (2015). "Gabapentin Therapy in Psychiatric Disorders: A Systematic Review". The Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders. 17 (5). doi:10.4088/PCC.15r01821. PMC 4732322. PMID 26835178.

- ^ Ahmed S, Stanciu CN, Kotapati PV, Ahmed R, Bhivandkar S, Khan AM, et al. (August 2019). "Effectiveness of Gabapentin in Reducing Cravings and Withdrawal in Alcohol Use Disorder: A Meta-Analytic Review". The Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders. 21 (4). doi:10.4088/PCC.19r02465. PMID 31461226. S2CID 201662179.

- ^ Kranzler HR, Feinn R, Morris P, Hartwell EE (September 2019). "A meta-analysis of the efficacy of gabapentin for treating alcohol use disorder". Addiction. 114 (9): 1547–1555. doi:10.1111/add.14655. PMC 6682454. PMID 31077485.

- ^ a b Mason BJ, Quello S, Shadan F (January 2018). "Gabapentin for the treatment of alcohol use disorder". Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs. 27 (1): 113–124. doi:10.1080/13543784.2018.1417383. PMC 5957503. PMID 29241365.

- ^ Sood A, Ebbert JO, Wyatt KD, Croghan IT, Schroeder DR, Sood R, et al. (March 2010). "Gabapentin for smoking cessation". Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 12 (3): 300–304. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntp195. PMC 2825098. PMID 20081039.

- ^ Behnam B, Semnani V, Saghafi N, Ghorbani R, Dianak Shori M, Ghooshchian Choobmasjedi S (2012). "Gabapentin Effect on Pain Associated with Heroin Withdrawal in Iranian Crack: a Randomized Double-blind Clinical Trial". Iranian Journal of Pharmaceutical Research. 11 (3): 979–983. PMC 3813133. PMID 24250527.

- ^ Nielsen S, Gowing L, Sabioni P, Le Foll B (January 2019). "Pharmacotherapies for cannabis dependence". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1 (1): CD008940. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008940.pub3. PMC 6360924. PMID 30687936.

- ^ McLean RJ, Gottlob I (August 2009). "The pharmacological treatment of nystagmus: a review". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 10 (11): 1805–1816. doi:10.1517/14656560902978446. PMID 19601699. S2CID 21477128.

- ^ Thurtell MJ, Leigh RJ (February 2012). "Treatment of nystagmus". Current Treatment Options in Neurology. 14 (1): 60–72. doi:10.1007/s11940-011-0154-5. PMID 22072056. S2CID 40370476.

- ^ Mehta AR, Kennard C (June 2012). "The pharmacological treatment of acquired nystagmus". Practical Neurology. 12 (3): 147–153. doi:10.1136/practneurol-2011-000181. PMID 22661344. S2CID 1950738.

- ^ Shan D, Zou L, Liu X, Shen Y, Cai Y, Zhang J (June 2020). "Efficacy and safety of gabapentin and pregabalin in patients with vasomotor symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 222 (6): 564–579.e12. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2019.12.011. PMID 31870736. S2CID 209462426.

- ^ Otero-Romero S, Sastre-Garriga J, Comi G, Hartung HP, Soelberg Sørensen P, Thompson AJ, et al. (October 2016). "Pharmacological management of spasticity in multiple sclerosis: Systematic review and consensus paper". Multiple Sclerosis. 22 (11): 1386–1396. doi:10.1177/1352458516643600. PMID 27207462. S2CID 25028259.

- ^ Winkelmann J, Allen RP, Högl B, Inoue Y, Oertel W, Salminen AV, et al. (July 2018). "Treatment of restless legs syndrome: Evidence-based review and implications for clinical practice (Revised 2017)§". Movement Disorders. 33 (7): 1077–1091. doi:10.1002/mds.27260. PMID 29756335. S2CID 21669996.

- ^ Berger TG, Steinhoff M (June 2011). "Pruritus and renal failure". Seminars in Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery. 30 (2): 99–100. doi:10.1016/j.sder.2011.04.005 (inactive 1 November 2024). PMC 3692272. PMID 21767770.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ Hercz D, Jiang SH, Webster AC (December 2020). "Interventions for itch in people with advanced chronic kidney disease". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (12): CD011393. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011393.pub2. PMC 8094883. PMID 33283264.

- ^ Anand S (March 2013). "Gabapentin for pruritus in palliative care". The American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Care. 30 (2): 192–196. doi:10.1177/1049909112445464. PMID 22556282. S2CID 39737885.

- ^ Schneider SA, Deuschl G (January 2014). "The treatment of tremor". Neurotherapeutics. 11 (1): 128–138. doi:10.1007/s13311-013-0230-5. PMC 3899476. PMID 24142589.

- ^ Zesiewicz TA, Elble RJ, Louis ED, Gronseth GS, Ondo WG, Dewey RB, et al. (November 2011). "Evidence-based guideline update: treatment of essential tremor: report of the Quality Standards subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology". Neurology. 77 (19): 1752–1755. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e318236f0fd. PMC 3208950. PMID 22013182.

- ^ Sadeghi R, Ondo WG (December 2010). "Pharmacological management of essential tremor". Drugs. 70 (17): 2215–2228. doi:10.2165/11538180-000000000-00000. PMID 21080739. S2CID 10662268.

- ^ Ng QX, Han MX, Teoh SE, Yaow CY, Lim YL, Chee KT (August 2021). "A Systematic Review of the Clinical Use of Gabapentin and Pregabalin in Bipolar Disorder". Pharmaceuticals. 14 (9): 834. doi:10.3390/ph14090834. PMC 8469561. PMID 34577534.

- ^ Tran DQ, Duong S, Bertini P, Finlayson RJ (February 2010). "Treatment of complex regional pain syndrome: a review of the evidence". Canadian Journal of Anaesthesia. 57 (2): 149–166. doi:10.1007/s12630-009-9237-0. PMID 20054678.

- ^ Hamilton TW, Strickland LH, Pandit HG (August 2016). "A Meta-Analysis on the Use of Gabapentinoids for the Treatment of Acute Postoperative Pain Following Total Knee Arthroplasty". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume. 98 (16): 1340–1350. doi:10.2106/jbjs.15.01202. PMID 27535436. Archived from the original on 29 September 2020. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- ^ Aazh H, El Refaie A, Humphriss R (December 2011). "Gabapentin for tinnitus: a systematic review". American Journal of Audiology. 20 (2): 151–158. doi:10.1044/1059-0889(2011/10-0041). PMID 21940981.

- ^ Linde M, Mulleners WM, Chronicle EP, McCrory DC (June 2013). "Gabapentin or pregabalin for the prophylaxis of episodic migraine in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013 (6): CD010609. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010609. PMC 6599858. PMID 23797675.

- ^ Shanthanna H, Gilron I, Rajarathinam M, AlAmri R, Kamath S, Thabane L, et al. (August 2017). "Benefits and safety of gabapentinoids in chronic low back pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". PLOS Medicine. 14 (8): e1002369. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002369. PMC 5557428. PMID 28809936.

- ^ Domecq JP, Prutsky G, Leppin A, Sonbol MB, Altayar O, Undavalli C, et al. (February 2015). "Clinical review: Drugs commonly associated with weight change: a systematic review and meta-analysis". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 100 (2): 363–370. doi:10.1210/jc.2014-3421. PMC 5393509. PMID 25590213.

- ^ Yang Y, Wang X (January 2016). "Sexual dysfunction related to antiepileptic drugs in patients with epilepsy". Expert Opinion on Drug Safety. 15 (1): 31–42. doi:10.1517/14740338.2016.1112376. PMID 26559937. S2CID 39571068.

- ^ Kim JB, Jung JM, Park MH, Lee EJ, Kwon DY (November 2017). "Negative myoclonus induced by gabapentin and pregabalin: A case series and systematic literature review". Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 382: 36–39. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2017.09.019. PMID 29111014. S2CID 32010921.

- ^ Desai A, Kherallah Y, Szabo C, Marawar R (March 2019). "Gabapentin or pregabalin induced myoclonus: A case series and literature review". Journal of Clinical Neuroscience. 61: 225–234. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2018.09.019. PMID 30381161. S2CID 53165515.

- ^ "Side effects of gabapentin". National Health Service. 16 September 2021. Retrieved 20 January 2024.

- ^ a b Patorno E, Bohn RL, Wahl PM, Avorn J, Patrick AR, Liu J, et al. (April 2010). "Anticonvulsant medications and the risk of suicide, attempted suicide, or violent death". JAMA. 303 (14): 1401–1409. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.410. PMID 20388896.

- ^ Leith WM, Lambert WE, Boehnlein JK, Freeman MD (January 2019). "The association between gabapentin and suicidality in bipolar patients". International Clinical Psychopharmacology. 34 (1): 27–32. doi:10.1097/YIC.0000000000000242. PMID 30383553. S2CID 54130760.

- ^ Molero Y, Larsson H, D'Onofrio BM, Sharp DJ, Fazel S (June 2019). "Associations between gabapentinoids and suicidal behaviour, unintentional overdoses, injuries, road traffic incidents, and violent crime: population based cohort study in Sweden". BMJ. 365: l2147. doi:10.1136/bmj.l2147. PMC 6559335. PMID 31189556.

- ^ Gibbons, R., Hur, K., Lavigne, J., Wang, J., & Mann, J. J. (2019). Medications and Suicide: High Dimensional Empirical Bayes Screening (iDEAS). Harvard Data Science Review, 1(2). https://doi.org/10.1162/99608f92.6fdaa9de

- ^ a b "FDA warns about serious breathing problems with seizure and nerve pain medicines gabapentin (Neurontin, Gralise, Horizant) and pregabalin (Lyrica, Lyrica CR)". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 19 December 2019. Archived from the original on 22 December 2019. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Rahman AA, Dell'Aniello S, Moodie EE, Durand M, Coulombe J, Boivin JF, et al. (January 2024). "Gabapentinoids and Risk for Severe Exacerbation in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Population-Based Cohort Study". Annals of Internal Medicine. 177 (Online ahead of print): 144–154. doi:10.7326/M23-0849. PMID 38224592. S2CID 266985259.

- ^ a b c d Mersfelder TL, Nichols WH (March 2016). "Gabapentin: Abuse, Dependence, and Withdrawal". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 50 (3): 229–233. doi:10.1177/1060028015620800. PMID 26721643. S2CID 21108959.

- ^ a b c d Bonnet U, Scherbaum N (December 2017). "How addictive are gabapentin and pregabalin? A systematic review". European Neuropsychopharmacology. 27 (12): 1185–1215. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2017.08.430. PMID 28988943. S2CID 10345555.

- ^ Bonnet U, Richter EL, Isbruch K, Scherbaum N (June 2018). "On the addictive power of gabapentinoids: a mini-review" (PDF). Psychiatria Danubina. 30 (2): 142–149. doi:10.24869/psyd.2018.142. PMID 29930223. S2CID 49344251.

- ^ R.C. Baselt, Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man, 8th edition, Biomedical Publications, Foster City, CA, 2008, pp. 677–8. ISBN 978-0-9626523-7-0.

- ^ Vartanian MG, Radulovic LL, Kinsora JJ, Serpa KA, Vergnes M, Bertram E, et al. (March 2006). "Activity profile of pregabalin in rodent models of epilepsy and ataxia". Epilepsy Research. 68 (3): 189–205. doi:10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2005.11.001. PMID 16337109.

- ^ Cheng JK, Chiou LC (2006). "Mechanisms of the antinociceptive action of gabapentin". Journal of Pharmacological Sciences. 100 (5): 471–486. doi:10.1254/jphs.CR0050020. PMID 16474201.

- ^ a b c d e Sills GJ (February 2006). "The mechanisms of action of gabapentin and pregabalin". Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 6 (1): 108–113. doi:10.1016/j.coph.2005.11.003. PMID 16376147.

- ^ a b c d e f Calandre EP, Rico-Villademoros F, Slim M (November 2016). "Alpha2delta ligands, gabapentin, pregabalin and mirogabalin: a review of their clinical pharmacology and therapeutic use". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 16 (11): 1263–1277. doi:10.1080/14737175.2016.1202764. PMID 27345098. S2CID 33200190.

- ^ Taylor CP, Harris EW (July 2020). "Analgesia with Gabapentin and Pregabalin May Involve N-Methyl-d-Aspartate Receptors, Neurexins, and Thrombospondins". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 374 (1): 161–174. doi:10.1124/jpet.120.266056. PMID 32321743.

- ^ a b Dooley DJ, Taylor CP, Donevan S, Feltner D (February 2007). "Ca2+ channel alpha2delta ligands: novel modulators of neurotransmission". Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 28 (2): 75–82. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2006.12.006. PMID 17222465.

- ^ Davies A, Hendrich J, Van Minh AT, Wratten J, Douglas L, Dolphin AC (May 2007). "Functional biology of the alpha(2)delta subunits of voltage-gated calcium channels". Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 28 (5): 220–228. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2007.03.005. PMID 17403543.

- ^ Manville RW, Abbott GW (October 2018). "Gabapentin Is a Potent Activator of KCNQ3 and KCNQ5 Potassium Channels". Molecular Pharmacology. 94 (4): 1155–1163. doi:10.1124/mol.118.112953. PMC 6108572. PMID 30021858.

- ^ a b Goldlust A, Su TZ, Welty DF, Taylor CP, Oxender DL (September 1995). "Effects of anticonvulsant drug gabapentin on the enzymes in metabolic pathways of glutamate and GABA". Epilepsy Research. 22 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1016/0920-1211(95)00028-9. PMID 8565962.

- ^ a b Grankvist N, Lagerborg KA, Jain M, Nilsson R (December 2018). "Gabapentin Can Suppress Cell Proliferation Independent of the Cytosolic Branched-Chain Amino Acid Transferase 1 (BCAT1)". Biochemistry. 57 (49): 6762–6766. doi:10.1021/acs.biochem.8b01031. PMC 6528808. PMID 30427175.

- ^ del Amo EM, Urtti A, Yliperttula M (October 2008). "Pharmacokinetic role of L-type amino acid transporters LAT1 and LAT2". European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 35 (3): 161–174. doi:10.1016/j.ejps.2008.06.015. PMID 18656534.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Bockbrader HN, Wesche D, Miller R, Chapel S, Janiczek N, Burger P (October 2010). "A comparison of the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of pregabalin and gabapentin". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 49 (10): 661–669. doi:10.2165/11536200-000000000-00000. PMID 20818832. S2CID 16398062.

- ^ a b c d Dickens D, Webb SD, Antonyuk S, Giannoudis A, Owen A, Rädisch S, et al. (June 2013). "Transport of gabapentin by LAT1 (SLC7A5)". Biochemical Pharmacology. 85 (11): 1672–1683. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2013.03.022. PMID 23567998.

- ^ a b Geldenhuys WJ, Mohammad AS, Adkins CE, Lockman PR (2015). "Molecular determinants of blood-brain barrier permeation". Therapeutic Delivery. 6 (8): 961–971. doi:10.4155/tde.15.32. PMC 4675962. PMID 26305616.

- ^ a b Müller CE (November 2009). "Prodrug approaches for enhancing the bioavailability of drugs with low solubility". Chemistry & Biodiversity. 6 (11): 2071–2083. doi:10.1002/cbdv.200900114. PMID 19937841. S2CID 32513471.

- ^ Boado RJ, Li JY, Nagaya M, Zhang C, Pardridge WM (October 1999). "Selective expression of the large neutral amino acid transporter at the blood-brain barrier". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 96 (21): 12079–12084. Bibcode:1999PNAS...9612079B. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.21.12079. PMC 18415. PMID 10518579.

- ^ Ma J, Björnsson ES, Chalasani N (February 2024). "The Safe Use of Analgesics in Patients with Cirrhosis: A Narrative Review". Am J Med. 137 (2): 99–106. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2023.10.022. PMID 37918778. S2CID 264888110.

- ^ Agarwal P, Griffith A, Costantino HR, Vaish N (May 2010). "Gabapentin enacarbil - clinical efficacy in restless legs syndrome". Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 6: 151–158. doi:10.2147/NDT.S5712. PMC 2874339. PMID 20505847.

- ^ Kaye AD (5 June 2017). Pharmacology, An Issue of Anesthesiology Clinics E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 98–. ISBN 978-0-323-52998-3.

- ^ Wyllie E, Cascino GD, Gidal BE, Goodkin HP (17 February 2012). Wyllie's Treatment of Epilepsy: Principles and Practice. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 423. ISBN 978-1-4511-5348-4.

- ^ Benzon H, Rathmell JP, Wu CL, Turk DC, Argoff CE, Hurley RW (11 September 2013). Practical Management of Pain. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 1006. ISBN 978-0-323-17080-2.

- ^ a b Sneader W (2005). Drug Discovery: A History. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 219–220. ISBN 978-0-470-01552-0.

- ^ Levandovskiy IA, Sharapa DI, Shamota TV, Rodionov VN, Shubina TE (February 2011). "Conformationally restricted GABA analogs: from rigid carbocycles to cage hydrocarbons". Future Medicinal Chemistry. 3 (2): 223–241. doi:10.4155/fmc.10.287. PMID 21428817.

- ^ Chen Z, Mondal A, Minor DL (June 2023). "Structural basis for CaVα2δ:gabapentin binding". Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 30 (6): 735–739. doi:10.1038/s41594-023-00951-7. PMC 10896480. PMID 36973510.

- ^ Kumar A, Soudagar SR, Nijasure AM, Panda NB, Gautam P, Thakur GR. "Process For Synthesis Of Gabapentin".

- ^ a b US4024175A, Satzinger G, Hartenstein J, Herrmann M, Heldt W, "Cyclic amino acids", issued 1977-05-17

- ^ Johnson DS, Li JJ (26 February 2013). The Art of Drug Synthesis. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 13–. ISBN 978-1-118-67846-6.

- ^ Reimann W (October 1983). "Inhibition by GABA, baclofen and gabapentin of dopamine release from rabbit caudate nucleus: are there common or different sites of action?". European Journal of Pharmacology. 94 (3–4): 341–344. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(83)90425-9. PMID 6653664.

- ^ Prevo AJ, Slootman HJ, Harlaar J, Vogelaar TW (1985). "A new antispastic agent: gabapentin: its effect on EMG analysis during voluntary movement in hemiplegia". Clinical Neurophysiology. 62 (3): S221. doi:10.1016/0013-4694(85)90838-7.

- ^ Wessely P, Baumgartner C, Klingler D, Kreczi J, Meyerson N, Sailer L, et al. (1987). "Preliminary Results Of A Double Blind Study With The New Migraine Prophylactic Drug Gabapentin". Cephalalgia. 7 (6_suppl): 477–478. doi:10.1177/03331024870070S6214. ISSN 0333-1024.

- ^ Crawford P, Ghadiali E, Lane R, Blumhardt L, Chadwick D (June 1987). "Gabapentin as an antiepileptic drug in man". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 50 (6): 682–686. doi:10.1136/jnnp.50.6.682. PMC 1032070. PMID 3302110.

- ^ "Drug Profile: Gabapentin". Adis Insight.

- ^ Mack A (2003). "Examination of the evidence for off-label use of gabapentin" (PDF). Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy. 9 (6): 559–568. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2003.9.6.559. PMC 10437292. PMID 14664664. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 September 2010. Retrieved 15 August 2006.

- ^ Irving G (September 2012). "Once-daily gastroretentive gabapentin for the management of postherpetic neuralgia: an update for clinicians". Therapeutic Advances in Chronic Disease. 3 (5): 211–218. doi:10.1177/2040622312452905. PMC 3539268. PMID 23342236.

- ^ Orrange S (31 May 2013). "Yabba Dabba Gabapentin: Are Gralise and Horizant Worth the Cost?". GoodRx, Inc. Archived from the original on 23 June 2018. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ^ "Gabapentin controlled release – Depomed". Adis Insight.

- ^ Span P (17 August 2024). "The Painkiller Used for Just About Anything". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 December 2024.

- ^ "Pregabalin and gabapentin will become controlled drugs in April". NursingNotes. 17 October 2018. Archived from the original on 16 June 2019. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

- ^ "Re: Pregabalin and Gabapentin advice" (PDF). GOV.UK. 14 January 2016.

- ^ "Pregabalin and gabapentin: proposal to schedule under the Misuse of Drugs Regulations 2001". GOV.UK. 10 November 2017. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- ^ Mayor S (October 2018). "Pregabalin and gabapentin become controlled drugs to cut deaths from misuse". BMJ. 363: k4364. doi:10.1136/bmj.k4364. PMID 30327316. S2CID 53520780.

- ^ "Pregabalin and gabapentin to be controlled as Class C drugs". GOV.UK. 15 October 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- ^ "Gabapentin (Neurontin)" (PDF). Drug Enforcement Administration. January 2023.

- ^ "Important Notice: Gabapentin Becomes a Schedule 5 Controlled Substance in Kentucky" (PDF). Kentucky State Board of Pharmacy. March 2017. Retrieved 18 June 2018.

- ^ "WV Code 212". West Virginia Legislature. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ "Gabapentin will be a Schedule V controlled substance in Tennessee effective July 1, 2018" (PDF). tn.gov. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ "Pharmacy Division". Alabama Department of Public Health (ADPH). Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ "Controlled Substances Amendments". Utah State Legislature. Retrieved 12 April 2024.

- ^ "Scheduling of Gabapentin" (PDF). Virginia Department of Health Professions. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- ^ Mack A (2003). "Examination of the evidence for off-label use of gabapentin". Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy. 9 (6): 559–568. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2003.9.6.559. PMC 10437292. PMID 14664664. S2CID 17085492.

- ^ Reinares M, Rosa AR, Franco C, Goikolea JM, Fountoulakis K, Siamouli M, et al. (March 2013). "A systematic review on the role of anticonvulsants in the treatment of acute bipolar depression". The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 16 (2): 485–496. doi:10.1017/S1461145712000491. PMID 22575611.

- ^ Tansey B (14 May 2004). "Huge penalty in drug fraud, Pfizer settles felony case in Neurontin off-label promotion". San Francisco Chronicle. p. C-1. Archived from the original on 23 June 2006.

- ^ a b Berkrot B (25 March 2010). "US jury's Neurontin ruling to cost Pfizer $141 mln". Reuters. Archived from the original on 19 October 2015.

- ^ a b "Pfizer faces $142M in damages for drug fraud". Bloomberg Businessweek. 25 March 2010. Archived from the original on 19 October 2015. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- ^ Van Voris B, Lawrence J (26 March 2010). "Pfizer Told to Pay $142.1 Million for Neurontin Marketing Fraud". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- ^ a b Husgen J (3 October 2013). "Pfizer Appeal Targets Fraudulent Drug Marketing Claims Brought Under Civil RICO Statute". Healthcare Law Insights. Hugh Blackwell.

- ^ Hurley L (9 December 2013). "US high court leaves intact $142 million verdict against Pfizer". Reuters.

- ^ "Pfizer Inc. v. Kaiser Foundation Health Plan, Inc.: Petition for certiorari denied on December 9, 2013". SCOTUSBlog.

- ^ a b c Pelley S, ed. (7 December 2007). "Prescription For Addiction". 60 Minutes. CBS News.

- ^ "Prometa Founder's Spotty Background Explored". 3 November 2006. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015.

- ^ "United States V. Terren S. Peizer". www.justice.gov. 1 March 2023.

- ^ "Prometa under fire in Washington drug court program". Alcoholism & Drug Abuse Weekly. 20 (3). 21 January 2008. doi:10.1002/adaw.20121.

- ^ Ling W, Shoptaw S, Hillhouse M, Bholat MA, Charuvastra C, Heinzerling K, et al. (February 2012). "Double-blind placebo-controlled evaluation of the PROMETA™ protocol for methamphetamine dependence". Addiction. 107 (2): 361–369. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03619.x. PMC 4122522. PMID 22082089.

- ^ a b Alpert B (7 November 2005). "Curb Your Cravings For This Stock". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Schuster H, Peterson R (7 December 2007). "Prescription For Addiction". CBS News.

- ^ Huus K (5 February 2007). "Unproven meth, cocaine 'remedy' hits market". NBC News.

- ^ Humphreys K (24 January 2012). "The Rise and Fall of a "Miracle Cure" for Drug Addiction". Washington Monthly.

- ^ Ramshaw E (20 January 2008). "Texas' Prometa program for treating meth addicts draws skeptics". Dallas Morning News. Archived from the original on 27 October 2010.

- ^ Feuerstein A (13 November 2007). "Hythiam, Shire, Genentech; Talk is proving cheap at Hythiam". Biotech Notebook. TheStreet.

- ^ Chan AY, Yuen AS, Tsai DH, Lau WC, Jani YH, Hsia Y, et al. (August 2023). "Gabapentinoid consumption in 65 countries and regions from 2008 to 2018: a longitudinal trend study" (PDF). Nature Communications. 14 (1): 5005. Bibcode:2023NatCo..14.5005C. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-40637-8. PMC 10435503. PMID 37591833.

- ^ "Gralise Approval History". Drugs.com.

- ^ "Pfizer Completes Transaction to Combine Its Upjohn Business with Mylan". Pfizer. 16 November 2020. Retrieved 17 June 2024 – via Business Wire.

- ^ "Neurontin". Pfizer. Retrieved 17 June 2024.

- ^ "Brands". Viatris. 16 November 2020. Retrieved 17 June 2024.

- ^ Baillie JK, Power I (January 2006). "The mechanism of action of gabapentin in neuropathic pain". Current Opinion in Investigational Drugs. 7 (1): 33–39. PMID 16425669.

- ^ Kjellsson MC, Ouellet D, Corrigan B, Karlsson MO (October 2011). "Modeling sleep data for a new drug in development using markov mixed-effects models". Pharmaceutical Research. 28 (10): 2610–2627. doi:10.1007/s11095-011-0490-x. PMID 21681607. S2CID 22241527.

- ^ Landmark CJ, Johannessen SI (February 2008). "Modifications of antiepileptic drugs for improved tolerability and efficacy". Perspectives in Medicinal Chemistry. 2: 21–39. doi:10.1177/1177391X0800200001. PMC 2746576. PMID 19787095.

- ^ Smith BH, Higgins C, Baldacchino A, Kidd B, Bannister J (August 2012). "Substance misuse of gabapentin". The British Journal of General Practice. 62 (601): 406–407. doi:10.3399/bjgp12X653516. PMC 3404313. PMID 22867659.

- ^ Shebak S, Varipapa R, Snyder A, Whitham MD, Milam TR (2014). "Gabapentin abuse and overdose: a case report" (PDF). J Subst Abus Alcohol. 2: 1018. S2CID 8959463. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 March 2019.

- ^ Martinez GM, Olabisi J, Ruekert L, Hasan S (July 2019). "A Call for Caution in Prescribing Gabapentin to Individuals With Concurrent Polysubstance Abuse: A Case Report". Journal of Psychiatric Practice. 25 (4): 308–312. doi:10.1097/PRA.0000000000000403. PMID 31291212. S2CID 195878855.

- ^ Trestman RL, Appelbaum KL, Metzner JL (April 2015). Oxford Textbook of Correctional Psychiatry. Oxford University Press. p. 167. ISBN 978-0-19-936057-4.

- ^ Goodman CW, Brett AS (August 2017). "Gabapentin and Pregabalin for Pain - Is Increased Prescribing a Cause for Concern?". The New England Journal of Medicine. 377 (5): 411–414. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1704633. PMID 28767350.

- ^ Evoy KE, Morrison MD, Saklad SR (March 2017). "Abuse and Misuse of Pregabalin and Gabapentin". Drugs. 77 (4): 403–426. doi:10.1007/s40265-017-0700-x. PMID 28144823. S2CID 24396685.

- ^ Bonnet U, Scherbaum N (February 2018). "[On the risk of dependence on gabapentinoids]". Fortschritte der Neurologie-Psychiatrie (in German). 86 (2): 82–105. doi:10.1055/s-0043-122392. PMID 29179227.

- ^ Reynolds K, Kaufman R, Korenoski A, Fennimore L, Shulman J, Lynch M (July 2020). "Trends in gabapentin and baclofen exposures reported to U.S. poison centers". Clinical Toxicology. 58 (7): 763–772. doi:10.1080/15563650.2019.1687902. PMID 31786961. S2CID 208537638.

- ^ Faryar KA, Webb AN, Bhandari B, Price TG, Bosse GM (June 2019). "Trending gabapentin exposures in Kentucky after legislation requiring the use of the state prescription drug monitoring program for all opioid prescriptions". Clinical Toxicology. 57 (6): 398–403. doi:10.1080/15563650.2018.1538518. PMID 30676102. S2CID 59226292.

- ^ Smith RV, Havens JR, Walsh SL (July 2016). "Gabapentin misuse, abuse and diversion: a systematic review". Addiction. 111 (7): 1160–1174. doi:10.1111/add.13324. PMC 5573873. PMID 27265421.

- ^ Vettorato E, Corletto F (September 2011). "Gabapentin as part of multi-modal analgesia in two cats suffering multiple injuries". Veterinary Anaesthesia and Analgesia. 38 (5): 518–520. doi:10.1111/j.1467-2995.2011.00638.x. PMID 21831060.

- ^ van Haaften KA, Forsythe LR, Stelow EA, Bain MJ (November 2017). "Effects of a single preappointment dose of gabapentin on signs of stress in cats during transportation and veterinary examination". Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 251 (10): 1175–1181. doi:10.2460/javma.251.10.1175. PMID 29099247. S2CID 7780988.

- ^ a b c "Gabapentin". Plumb's Veterinary Drugs. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ^ a b Coile C (31 October 2022). "Gabapentin for Dogs: Uses and Side Effects". American Kennel Club. Archived from the original on 6 December 2022. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- ^ Di Cesare F, Negro V, Ravasio G, Villa R, Draghi S, Cagnardi P (June 2023). "Gabapentin: Clinical Use and Pharmacokinetics in Dogs, Cats, and Horses". Animals. 13 (12): 2045. doi:10.3390/ani13122045. PMC 10295034. PMID 37370556.

- ^ Kirby-Madden T, Waring CT, Herron M (May 2024). "Effects of Gabapentin on the Treatment of Behavioral Disorders in Dogs: A Retrospective Evaluation". Animals. 14 (10): 1462. doi:10.3390/ani14101462. PMC 11117262. PMID 38791679.