National Reconnaissance Office

| |

NRO headquarters at night | |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | Established: August 25, 1960 Declassified: September 18, 1992 |

| Jurisdiction | United States |

| Headquarters | Chantilly, Virginia, U.S. |

| Motto | Supra Et Ultra (Above And Beyond) |

| Annual budget | Classified |

| Agency executive |

|

| Parent agency | Department of Defense |

| Website | www |

| Part of a series on the |

| United States space program |

|---|

|

The National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) is a member of the United States Intelligence Community and an agency of the United States Department of Defense which designs, builds, launches, and operates the reconnaissance satellites of the U.S. federal government. It provides satellite intelligence to several government agencies, particularly signals intelligence (SIGINT) to the National Security Agency (NSA), imagery intelligence (IMINT) to the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA), and measurement and signature intelligence (MASINT) to the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA).[4] The NRO announced in 2023 that it plans within the following decade to quadruple the number of satellites it operates and increase the number of signals and images it delivers by a factor of ten.[5]

NRO is considered, along with the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), NSA, DIA, and NGA, to be one of the "big five" U.S. intelligence agencies.[6] The NRO is headquartered in Chantilly, Virginia,[7] 2 miles (3.2 km) south of the Washington Dulles International Airport.

The Director of the NRO reports to both the Director of National Intelligence and the Secretary of Defense.[8] The NRO's federal workforce is a hybrid organization consisting of some 3,000 personnel including NRO cadre, Air Force, Army, CIA, NGA, NSA, Navy and US Space Force[9] personnel.[10] A 1996 bipartisan commission report described the NRO as having by far the largest budget of any intelligence agency, and "virtually no federal workforce", accomplishing most of its work through "tens of thousands" of defense contractor personnel.[11] From its founding in 1961 the NRO's existence was classified and not revealed publicly until 1992.[12]

Mission

[edit]The National Reconnaissance Office develops, builds, launches, and operates space reconnaissance systems and conducts intelligence-related activities for U.S. national security.[13][14]

The NRO also coordinates collection and analysis of information from airplane and satellite reconnaissance by the military services and the Central Intelligence Agency.[15] It is funded through the National Reconnaissance Program, which is part of the National Intelligence Program (formerly known as the National Foreign Intelligence Program).[16] The agency is part of the Department of Defense.

The NRO works closely with its intelligence and space partners, which include the National Security Agency (NSA), the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA), the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA), the United States Strategic Command, the United States Space Command, Naval Research Laboratory, and other agencies and organizations.

History

[edit]

The NRO was established on August 25, 1960, after management problems and insufficient progress with the USAF satellite reconnaissance program (see SAMOS and MIDAS).[17]: 23 [18] The formation was based on a 25 August 1960 recommendation to President Dwight D. Eisenhower during a special National Security Council meeting, and the agency was to coordinate the USAF and CIA's (and later the navy and NSA's) reconnaissance activities.[17]: 46

The NRO's first photo reconnaissance satellite program was the Corona program,[19]: 25–28 the existence of which was declassified February 24, 1995, and which existed from August 1960 to May 1972 (although the first test flight occurred on February 28, 1959). The Corona system used (sometimes multiple) film capsules dropped by satellites, which were recovered mid-air by military craft. The first successful recovery from space (Discoverer XIII) occurred on August 12, 1960, and the first image from space was seen six days later. The first imaging resolution was 8 meters, which was improved to 2 meters. Individual images covered, on average, an area of about 10 by 120 miles (16 by 193 km). The last Corona mission (the 145th), was launched May 25, 1972, and this mission's last images were taken May 31, 1972. From May 1962 to August 1964, the NRO conducted 12 mapping missions as part of the "Argon" system. Only seven were successful.[19]: 25–28 In 1963, the NRO conducted a mapping mission using higher resolution imagery, as part of the "Lanyard" program. The Lanyard program flew one successful mission.[20]

NRO missions since 1972 are classified, and portions of many earlier programs remain unavailable to the public.

On August 18, 2000, the National Reconnaissance Office recognized its ten original Founders. They were: William O. Baker, Merton E. Davies, Sidney Drell, Richard L. Garwin, Amrom Harry Katz, James R. Killian, Edwin H. Land, Frank W. Lehan, William J. Perry, Edward M. Purcell.[21] Although their early work was highly classified, this group of men went on to extraordinary public accomplishments, including a Secretary of Defense, a Nobel Laureate, a president of MIT, a recipient of the Presidential Medal of Science, a renowned planetary scientist, and more.

Existence

[edit]The NRO was first mentioned by the press in a 1971 New York Times article.[22][23] The first official acknowledgement of NRO was a Senate committee report in October 1973, which inadvertently exposed the existence of the NRO.[24] In 1985, a New York Times article revealed details on the operations of the NRO.[25]

Despite news coverage of NRO's existence, the United States intelligence community debated for 20 years whether to confirm the reports.[26] The existence of the NRO was declassified on September 18, 1992, by the Deputy Secretary of Defense, as recommended by the Director of Central Intelligence.[12] The brief press release did not mention the word "satellite", and the agency did not confirm for several more years that it launched satellites on rockets.[26]

Funding controversy

[edit]A Washington Post article in September 1995 reported that the NRO had quietly hoarded between $1 billion and $1.7 billion in unspent funds without informing the Central Intelligence Agency, the Pentagon, or Congress.[27]

The CIA was in the midst of an inquiry into the NRO's funding because of complaints that the agency had spent $300 million of hoarded funds from its classified budget to build a new headquarters building in Chantilly, Virginia, a year earlier.

In total, NRO had accumulated US$3.8 billion (inflation adjusted US$ 7.6 billion in 2024) in forward funding. As a consequence, NRO's three distinct accounting systems were merged.[28]

The presence of the classified new headquarters was revealed by the Federation of American Scientists who obtained unclassified copies of the blueprints filed with the building permit application. After 9/11 those blueprints were apparently classified. The reports of an NRO slush fund were true. According to former CIA general counsel Jeffrey Smith, who led the investigation: "Our inquiry revealed that the NRO had for years accumulated very substantial amounts as a 'rainy day fund.'"[29]

Future Imagery Architecture

[edit]In 1999 the NRO embarked on a $25 billion[30] project with Boeing entitled Future Imagery Architecture to create a new generation of imaging satellites. In 2002 the project was far behind schedule and would most likely cost $2 billion to $3 billion more than planned, according to NRO records. The government pressed forward with efforts to complete the project, but after two more years, several more review panels and billions more in expenditures, the project was killed in what a New York Times report called "perhaps the most spectacular and expensive failure in the 50-year history of American spy satellite projects."[31]

Mid-2000s to present

[edit]On August 23, 2001, Brian Patrick Regan, a civilian employee of TRW at NRO, was arrested at Dulles International Airport outside Washington while boarding a flight for Zurich. He was carrying coded information about Iraqi and Chinese missile sites. He also had the addresses of the Chinese and Iraqi Embassies in Switzerland and Austria. He was sentenced to life in prison without parole for offering to sell intelligence secrets to Iraq and China.[32]

In January 2008, the government announced that a reconnaissance satellite operated by the NRO would make an unplanned and uncontrolled re-entry into the Earth's atmosphere in the next several months. Satellite watching hobbyists said that it was likely the USA-193, built by Lockheed Martin Corporation, which failed shortly after achieving orbit in December 2006.[33] On February 14, 2008, the Pentagon announced that rather than allowing the satellite to make an uncontrolled re-entry while still in one piece, it would instead be shot down by a missile fired from a Navy cruiser.[34] The intercept took place on February 21, 2008, resulting in the satellite breaking up into multiple pieces.[35]

In July 2008, the NRO declassified the existence of its Synthetic Aperture Radar satellites, citing difficulty in discussing the creation of the Space-Based Radar with the United States Air Force and other entities.[36] In August 2009, FOIA archives were queried for a copy of the NRO video, "Satellite Reconnaissance: Secret Eyes in Space."[37] The seven-minute video chronicles the early days of the NRO and many of its early programs. It was proposed that the NRO share the imagery of the United States itself with the National Applications Office for domestic law enforcement purposes.[38] The NAO was disestablished in 2009. The NRO is a non-voting associate member of the Civil Applications Committee (CAC). The CAC is an inter-agency committee that coordinates and oversees the Federal- Civil use of classified collections. The CAC was officially chartered in 1975 by the Office of the President to provide Federal- Civil agencies access to National Systems data in support of mission responsibilities.[39] According to Asia Times Online, one important mission of NRO satellites is the tracking of non-US submarines on patrol or on training missions in the world's oceans and seas.[40] At the National Space Symposium in April 2010, NRO director General Bruce Carlson, United States Air Force (Retired) announced that until the end of 2011, NRO is embarking on "the most aggressive launch schedule that this organization has undertaken in the last twenty-five years. There are a number of very large and very critical reconnaissance satellites that will go into orbit in the next year to a year and a half."[41]

In 2012, a McClatchy investigation found that the NRO was possibly breaching ethical and legal boundaries by encouraging its polygraph examiners to extract personal and private information from DoD personnel during polygraph tests that were limited to counterintelligence issues.[42] Allegations of abusive polygraph practices were brought forward by former NRO polygraph examiners.[43] In 2014, an inspector general's report concluded that NRO failed to report felony admissions of child sexual abuse to law enforcement authorities. NRO obtained these criminal admissions during polygraph testing but never forwarded the information to police. NRO's failure to act in the public interest by reporting child sexual predators was first made public in 2012 by former NRO polygraph examiners.[44] On August 30, 2019, Donald Trump tweeted an image of “the catastrophic accident during final launch preparations for the Safir SLV Launch at Semnan Launch Site One in Iran”. The image almost certainly came from a satellite known as USA 224, according to Marco Langbroek, a satellite tracker based in the Netherlands. The satellite was launched by the National Reconnaissance Office in 2011.[45] On January 31, 2020, Rocket Lab successfully launched a NROL-151 payload for the NRO.[46]

On December 19, 2020, NROL-108 was successfully launched aboard SpaceX's Falcon 9 rocket.[47] On July 15, 2020, NROL-149 was successfully launched aboard the first launch of Northrop Grumman's new Minotaur IV rocket. On April 27, 2021, NROL-82 was successfully launched aboard United Launch Alliance’s Delta IV rocket.[48] On June 15, 2021, NROL-111, a set of three classified satellites,[49] was successfully launched aboard a Northrop Grumman Minotaur I rocket.[50] On July 13, 2022, NROL-162 was launched aboard a Rocket Lab Electron rocket from Mahia, New Zealand.[51] On September 24, 2022, NROL-91 (USA 338) was launched from Vandenberg Space Force Base's Space Launch Complex 6 (SLC-6) aboard a United Launch Alliance Delta IV Heavy.

In 2021, SpaceX reportedly won a $1.8 billion contract from the NRO to build a network of hundreds of spy satellites under its Starshield unit.[52][53] The satellites reportedly will be able to "track targets on the ground and share that data with U.S. intelligence and military officials... enabling the U.S. government to quickly capture continuous imagery of activities on the ground nearly anywhere on the globe."

Organization

[edit]

The NRO is part of the Department of Defense. The Director of the NRO is appointed by the President of the United States, by and with the consent of the Senate.[54] Traditionally, the position was given to either the Under Secretary of the Air Force or the Assistant Secretary of the Air Force for Space, but with the appointment of Donald Kerr as Director of the NRO in July 2005 the position is now independent. The Agency is organized as follows:[55]

Principal Deputy Director of the NRO (PDDNRO)

- Reports to and coordinates with the DNRO on all NRO activities and handles the daily management of the NRO with decision responsibility as delegated by the DNRO; and,

- In the absence of the Director, acts on behalf of the DNRO.

Deputy Director of the NRO (DDNRO)

- Senior USAF General Officer. Represents the civilian/uniformed USAF personnel assigned to the NRO;

- Assists both the DNRO and PDDNRO in the daily direction of the NRO; and,

- Coordinates activities between the USAF and the NRO.

The Corporate Staff

- Encompasses all those support functions such as legal, diversity, human resources, security/counterintelligence, procurement, public affairs, etc. necessary for the day-to-day operation of the NRO and in support of the DNRO, PDNRO, and DDNRO.

Office of Space Launch (OSL)

- Responsible for all aspects of a satellite launch including launch vehicle hardware, launch services integration, mission assurance, operations, transportation, and mission safety; and,

- OSL is NRO's launch representative with industry, the USAF, and NASA.

Advanced Systems and Technology Directorate (AS&T)

- Invents and delivers advanced technologies;

- Develops new sources and methods; and,

- Enables multi-intelligence solutions.

Business Plans and Operations (BPO)

- Responsible for all financial and budgetary aspects of NRO programs and operations; and,

- Coordinates all legislative, international, and public affairs communications.

Communications Systems Acquisition Directorate (COMM)

- Supports the NRO by providing communications services through physical and virtual connectivity; and,

- Enables the sharing of mission-critical information with mission partners and customers.

Ground Enterprise Directorate (GED)

- Provides an integrated ground system that sends timely information to users worldwide.

Geospatial Intelligence Systems Acquisition Directorate (GEOINT)

- Responsible for acquiring NRO's technologically advanced imagery collection systems, which provides geospatial intelligence data to the Intelligence Community and the military.

Management Services and Operations (MS&O)

- Provides services such as facilities support, transportation and warehousing, logistics, and other business support, which the NRO needs to operate on a daily basis.

Mission Operations Directorate (MOD)

- Operates, maintains and reports the status of NRO satellites and their associated ground systems;

- Manages the 24-hour NRO Operations Center (NROC) which, working with U.S Strategic Command, provides defensive space control and space protection, monitors satellite flight safety, and provides space situational awareness.

Mission Integration Directorate (MID)

- Engages with users of NRO systems to understand their operational and intelligence problems and provide solutions in collaboration with NRO's mission partners.

- Manages the Tactical Defense Space Reconnaissance (TacDSR) Program to directly answer emerging warfighting intelligence requirements of the Combatant Commands (CCMDs), Services, and other tactical users as funded by the Department of Defense (DoD) Military Intelligence Program (MIP).[56]

Signals Intelligence Systems Acquisition Directorate (SIGINT)

- This directorate builds and deploys NRO's signals intelligence satellite systems that collect communication, electronic, and foreign instrumentation signals intelligence.

Systems Engineering Directorate (SED)

- Provides beginning-to-end systems engineering for all of NRO's systems.

Personnel

[edit]In 2007, the NRO described itself as "a hybrid organization consisting of some 3,000 personnel and jointly staffed by members of the armed services, the Central Intelligence Agency and DOD civilian personnel."[57] Between 2010 and 2012, the workforce is expected to increase by 100.[58] The majority of workers for the NRO are private corporate contractors, with $7 billion of the agency's $8 billion budget going to private corporations.[19]: 178

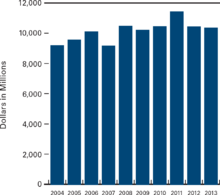

Budget

[edit]

The NRO derives its funding both from the US intelligence budget and the military budget. In 1971, the annual budget was estimated to be around $1 billion in nominal dollars ($ 7.5 billion real in 2024).[22] A 1975 report by the Congressional Commission on the Organization of the Government for the Conduct of Foreign Policy states that the NRO had "the largest budget of any intelligence agency".[25] By 1994, the annual budget had risen to $6 billion (inflation adjusted $ 12.3 billion in 2024),[59] and for 2010 it is estimated to amount to $15 billion (inflation adjusted $ 21 billion in 2024).[citation needed] This would correspond to 19% of the overall US intelligence budget of $80 billion for FY2010.[60] For Fiscal Year 2012 the budget request for science and technology included an increase to almost 6% (about $600 million) of the NRO budget after it had dropped to just about 3% of the overall budget in the years before.[58]

NRO directives and instructions

[edit]Under the Freedom of Information Act, the NRO declassified a list of secret directives for internal use. The following is a list of the released directives, which are available for download:

- NROD 10-2 – "National Reconnaissance Office External Management Policy"

- NROD 10-4 – "National Reconnaissance Office Sensitive Activities Management Group"

- NROD 10-5 – "Office of Corporate System Engineer Charter"

- NROD 22-1 – "Office of Inspector General"

- NROD 22-2 – "Employee Reports of Urgent Concerns to Congress"

- NROD 22-3 – "Obligations to report evidence of Possible Violations of Federal Criminal Law and Illegal Intelligence Activities"

- NROD 50-1 – "Executive Order 12333 – Intelligence Activities Affecting United States Persons"

- NROD 61-1 – "NRO Internet Policy, Information Technology"

- NROD 82-1a – "NRO Space Launch Management"

- NROD 110-2 – "National Reconnaissance Office Records and Information Management Program"

- NROD 120-1 – The NRO Military Uniform Wear Policy

- NROD 120-2 – "The NRO Awards and Recognition Programs"

- NROD 120-3 – "Executive Secretarial Panel"

- NROD 120-4 – "National Reconnaissance Pioneer Recognition Program"

- NROD 120-5 – "National Reconnaissance Office Utilization of the Intergovernmental Personnel Act Mobility Program"

- NROD 121-1 – "Training of NRO Personnel"

- NROI 150-4 – "Prohibited Items in NRO Headquarters Buildings/Property"

Coordination with USSPACECOM and USSF

[edit]At a mid-2019 press event just prior to the establishment of USSPACECOM, then-Air Force General John W. Raymond (set to lead the new command) stated that the NRO will "respond to the direction of the United States Space Command commander" to "protecting and defending those (space) capabilities". General Raymond further stated that "we [NRO and USSPACECOM] have a shared concept of operations, we have a shared vision and a shared concept of operations. We train together, we exercise together, we man the same C2 center, if you will, at the National Space Defense Center."[61]

In December 2019, the United States Space Force (USSF) was established, also helmed by Raymond, now a Space Force General and Chief of Space Operations (CSO).[62] NRO continued its close relationship with American military space operations, partnering with the Space Force's Space and Missile Systems Center (SMC) to manage the National Security Space Launch (NSSL) program, which uses government and contract spacecraft to launch important government payloads.[63][64] NSSL supports both the USSF and NRO, as well as the Navy.[64] NRO Director Scolese has characterized his agency as critical to American space dominance, stating that NRO provides "unrivaled situational awareness and intelligence to the best imagery and signals data on the planet."[63]

In August 2021, Scolese said he, Raymond, and Dickinson recently agreed to a Protect and Defend Strategic Framework covering national security in space and the relationship between DOD and the intelligence community on everything from acquisition to operations.[65]

Technology

[edit]NRO's technology is likely more advanced than its civilian equivalents. In the 1980s, the NRO had satellites and software that were capable of determining the exact dimensions of a tank gun.[25] In 2012 the agency donated two space telescopes to NASA. Despite being stored unused, the instruments are superior to the Hubble Space Telescope. One journalist observed, "If telescopes of this caliber are languishing on shelves, imagine what they're actually using."[66]

NMIS network

[edit]The NRO Management Information System (NMIS) is a computer network used to distribute NRO data classified as Top Secret. It is also known as the Government Wide Area Network (GWAN).[67]

Sentient AI satellite control system

[edit]Sentient is an automated (artificial intelligence) intelligence analysis system under development by the National Reconnaissance Office.[68][69] A principal purpose of the Sentient system is described by the NRO as "compiling at machine, versus human speed, synthesis of complex distributed data sources for rapid analysis faster than humans can manage".[70]

According to Robert Cardillo, a former director of the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, the Sentient system is intended to use "automated inferencing" to aid intelligence collection.[71] The Verge described Sentient as "an omnivorous analysis tool, capable of devouring data of all sorts, making sense of the past and present, anticipating the future, and pointing satellites toward what it determines will be the most interesting parts of that future."[68]

Spacecraft

[edit]

The NRO maintains four main satellite constellations:[72]

- NRO SIGINT constellation

- NRO GEOINT constellation

- NRO Communications Relay constellation

- NRO Reconnaissance constellation

The NRO spacecraft include:[73]

GEOINT imaging

[edit]- Keyhole series – Imagery intelligence:

- KH-1, KH-2, KH-3, KH-4, KH-4A, KH-4B Corona (1959–1972)

- KH-5 – Argon (1961–1962)

- KH-6— Lanyard (1963)

- KH-7 – Gambit (1963–1967)[74]

- KH-8 – Gambit (1966–1984)

- KH-9 – Hexagon and Big Bird (1971–1986)

- KH-10 – Dorian (cancelled)

- KH-11 – Kennan (or Kennen), Crystal, Improved Crystal, Ikon, and Evolved Enhanced CRYSTAL System (1976–2013)

- Samos – photo imaging (1960–1962)

- Misty/Zirconic – stealth IMINT

- Next Generation Electro-Optical (NGEO), modular system, designed for incremental improvements (in development).[75]

GEOINT radar

[edit]- Lacrosse/Onyx – radar imaging (1988–)

- TOPAZ (1–5) and TOPAZ Block 2[73]

SIGINT

[edit]- Samos-F – SIGINT (1962–1971)

- Poppy – ELINT program (1962–1971) continuing Naval Research Laboratory's GRAB (1960–1961), PARCAE and Improved PARCAE (1976-2008)[76]

- Jumpseat (1971–1983) and Trumpet (1994–2008) SIGINT

- Canyon (1968–1977), Vortex/Chalet (1978–1989) and Mercury (1994–1998) – SIGINT including COMINT

- Rhyolite/Aquacade (1970–1978), Magnum/Orion (1985–1990), and Mentor (1995–2010) – SIGINT

- NEMESIS (High Altitude)[73]

- ORION (High Altitude)[73]

- RAVEN (High Altitude)[73]

- INTRUDER (Low Altitude)[73]

- SIGINT High Altitude Replenishment Program (SHARP)

Space communications

[edit]- Quasar, communications relay[73]

- NROL-1 through NROL-66 – various secret satellites. NROL stands for National Reconnaissance Office Launch.

This list is likely to be incomplete, given the classified nature of many NRO spacecraft.

Locations

[edit]

In October 2008, NRO declassified five mission ground stations: three in the United States, near Washington, D.C.; Aurora, Colorado; and Las Cruces, New Mexico, and a presence at RAF Menwith Hill, UK, and at the Joint Defence Facility Pine Gap, Australia.

- NRO Headquarters 38°52′55″N 77°27′07″W / 38.882°N 77.452°W – Chantilly, Virginia

- Aerospace Data Facility-Colorado (ADF-C) 39°43′05″N 104°46′37″W / 39.718°N 104.777°W, Buckley Space Force Base, Aurora, Colorado

- Aerospace Data Facility-East (ADF-E) 38°44′10″N 77°09′29″W / 38.736°N 77.158°W, Fort Belvoir, Virginia

- Aerospace Data Facility-Southwest (ADF-SW) 32°30′07″N 106°36′40″W / 32.502°N 106.611°W, White Sands, New Mexico[78][79]

- NRO spacecraft launch offices reside at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, Florida and Vandenberg Space Force Base, California.[80]

In popular culture

[edit]- The NRO is featured in Dan Brown's novel Deception Point.

- Horror roleplaying game Delta Green features the "NRO section DELTA", a fictional black ops counter-intelligence section of the NRO controlled by Majestic 12 to hide the existence of UFOs and the supernatural. The Player characters can be agents of the NRO working with satellite intelligence, although not the ones in the "section DELTA" operations.

- In the film Mammoth, they are the men in black.

Image gallery

[edit]-

NRO Organization, circa 1971

-

NRO Organization, c. 2009

-

The Blues Brothers featured on the National Reconnaissance Office launch number 7 (NROL-7) mission patch

-

Patch commemorating launch of a classified payload National Reconnaissance Office launch number 11 (NROL-11) mission patch

-

The official mission patch from Launch-39

-

National Reconnaissance Operations Center

-

ADF-East Logo

-

ADF-Southwest Logo

-

ADF-Colorado Logo

See also

[edit]- List of NRO satellite launches

- National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency

- National Security Agency

- National Underwater Reconnaissance Office

- National Technical Means

- Reconnaissance satellite

References

[edit]- ^ "NRO - Directors: Christopher Scolese". www.nro.gov. Archived from the original on 2016-10-25. Retrieved 25 October 2016.

- ^ "PDDNRO".

- ^ "Bio- Brigadier General Christopher S. Povak" (PDF). Retrieved November 3, 2022.

- ^ Federation of American Scientists. "The Evolving Role of the NRO".

- ^ Hitchens, Theresa (October 10, 2023). "NRO plans 10-fold increase in imagery, signals intel output". Breaking Defense. Retrieved October 11, 2023.

- ^ Intelligence Agencies Must Operate More Like An Enterprise

- ^ "Contact the NRO Archived 2013-10-29 at the Wayback Machine" "National Reconnaissance Office Office of Public Affairs 14675 Lee Road Chantilly, VA 20151-1715"

- ^ Official NRO Fact Sheet via http://www.nro.gov, accessed March 2012

- ^ "NRO Airmen transfer to U.S. Space Force".

- ^ "Career Opportunities". Archived from the original on 2013-10-29. Retrieved 2013-07-08.

- ^ Commission on the Roles and Capabilities of the United States Intelligence Community. "Preparing for the 21st Century: An Appraisal of U.S. Intelligence, Chapter 13 – The Cost of Intelligence".

- ^ a b Jeffrey T. Richelson (September 18, 2008). "Out of the Black: The Declassification of the NRO". National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 257. National Security Archive. Retrieved 2008-10-13.

- ^ "National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) Center for the Study of National Reconnaissance (CSNR) Bulletin, Combined 2002 Issue" (PDF). Government Attic. Retrieved 26 October 2016.

- ^ "About_the_NRO".

- ^ "NRO Provides Support to the Warfighters". Press Release. NRO Press Office. 28 April 1998. Archived from the original on 18 June 2001. Retrieved 26 October 2016.

- ^ "U.S. Intelligence Community Budget". Office of the Director of Nation Intelligence.

- ^ a b Stares, Paul B. "The Militarization of Space". p. 23,46. Archived from the original on 2009-01-13. Retrieved 2008-11-24.

- ^ Jeffrey Richelson (1990). America's Secret Eyes in Space. Harper & Row.

- ^ a b c Paglen, Trevor (February 2009). Blank Spots On the Map: The Dark Geography of the Pentagon's Secret World. New York: Dutton.

- ^ Krebs, Gunter D. "KH-6 Lanyard". Gunter's Space Page. Retrieved January 14, 2023.

- ^ "NRO Honors Pioneers of National Reconnaissance" (PDF). NRO. August 18, 2000. Retrieved November 3, 2022.

- ^ a b (Chief, Special Security Center) (1974-01-07). "History of NRO security breaches" (PDF). National Reconnaissance Office. Retrieved 2010-12-22.

- ^ Welles, Benjamin (1971-01-22). "Foreign Policy: Disquiet Over Intelligence Setup". The New York Times. p. 1. Retrieved 2021-10-18.

The Pentagon's Defense Intelligence Agency has a staff of 3,000 and spends $500‐million yearly—as much as the C.I.A.— to collect and evaluate strategic intelligence. [...] Its National Reconnaissance Office spends another $1‐billion yearly flying reconnaissance airplanes and lofting or exploiting the satellites that constantly circle the earth and photograph enemy terrain with incredible accuracy from 130 miles up.

- ^ "CIA and Others: Secret Agencies Studied". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. Sarasota, Florida. Congressional Quarterly. 1973-12-19. p. 7-A. Retrieved 2021-10-19.

- ^ a b c Bamford, James (1985-01-13). "America's Supersecret Eyes In Space". The New York Times Magazine. p. 38. Retrieved 2021-10-19.

- ^ a b Day, Dwayne Allen (2023-01-23). "Not-so ancient astronauts and Area 51: the Skylab Incident". The Space Review. Retrieved 2023-01-24.

- ^ Pincus, Walter (1995-09-24). "Spy Agency Hoards Secret $1 Billion". Washington Post. p. A1. Retrieved 2021-10-19.

- ^ Fitzgerald, Dennis D. (2005). "Risk Management and National Reconnaissance From the Cold War Up to the Global War on Terrorism" (PDF). Journal of Discipline and Practice, 2005-U1. NRO/Federation of American Scientists. Retrieved 2023-01-13.

- ^ "Get Smarter: Demystifying the NRO". SECRECY & GOVERNMENT BULLETIN, Issue Number 39. Federation of American Scientists. August–September 1994. Retrieved 2008-10-13.

- ^ "Lack of Intelligence". U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on 2012-10-23.

- ^ Philip Taubman (2007-11-11). "Failure to Launch: In Death of Spy Satellite Program, Lofty Plans and Unrealistic Bids". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-11-12.

- ^ "Life Sentence for Bid to Sell Secrets to Iraq". The New York Times. 21 March 2003.

- ^ John Schwartz (2008-02-05). "Satellite Spotters Glimpse Secrets, and Tell Them". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-02-05.

- ^ David Stout and Thom Shanker (2008-02-14). "U.S. Officials Say Broken Satellite Will Be Shot Down". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-02-14.

- ^ "DoD Succeeds In Intercepting Non-Functioning Satellite (release=No. 0139-08)" (Press release). U.S. Department of Defense. February 20, 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-20.

- ^ Colin Clark (2008-07-03). "Spy Radar Satellites Declassified". DoD Buzz, through Military.com. Archived from the original on 2016-10-28. Retrieved 2008-07-10.

- ^ The Black Vault, "Download the declassified Satellite Reconnaissance: Secret Eyes in Space", NRO, August 2009.

- ^ "U.S. Reconnaissance Satellites: Domestic Targets – Documents Describe Use of Satellites in Support of Civil Agencies and Longstanding Controversy". National Security Archive, The George Washington University. 2008-04-11. Retrieved 2008-04-12.

- ^ "The Civil Applications Committee" (PDF). Federation of American Scientists. Retrieved November 3, 2022.

- ^ "US satellites shadow China's submarines". Pakistan Defence. 13 May 2010. Retrieved 26 October 2016.

- ^ Bruce Carlson (April 14, 2010). "Bruce Carlson, Director, NRO, National Space Symposium, Remarks" (PDF). National Reconnaissance Office. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 27, 2010. Retrieved 2010-06-04.

- ^ The IG complaint of Mark Phillips concerning the NRO | McClatchy. Mcclatchydc.com. Retrieved on 2013-07-21.

- ^ Taylor, Marisa, "Sen. Charles Grassley Seeks Probe Of Polygraph Techniques At National Reconnaissance Office", The McClatchy Company, 27 July 2012

- ^ Taylor, Marisa. (2014-04-22) WASHINGTON: IG: Feds didn't pass polygraph evidence of child abuse to investigators | Courts & Crime. McClatchy DC. Retrieved on 2014-04-28.

- ^ "SatTrackCam Leiden (B)log: Image from Trump tweet identified as imagery by USA 224, a classified KH-11 ENHANCED CRYSTAL satellite". September 2019.

- ^ Wall 2020-01-31T03:28:03Z, Mike (31 January 2020). "Rocket Lab launches satellite for US spysat agency, guides booster back to Earth". Space.com. Retrieved 2020-02-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Erwin, Sandra (December 19, 2020). "SpaceX wraps up 2020 with Falcon 9 launch of classified NRO satellite". spacenews.com. Retrieved June 29, 2021.

- ^ "Northrop Grumman Contributes to Successful National Security Launch". northropgrumman.com. 27 April 2021. Retrieved 16 May 2021.

- ^ Thompson, Amy (June 25, 2021). "Minotaur 1 rocket launches 3 classified spy satellites for National Reconnaissance Office". Space.com. Retrieved June 29, 2021.

- ^ Strout, Nathan (June 15, 2021). "National Reconnaissance Office launches 3 satellites off Virginia coast". C4ISRNET. Retrieved June 29, 2021.

- ^ Perez, Zamone (July 18, 2022). "Pentagon's National Reconnaissance Office says latest launches demonstrate speed, agility". Defense News. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- ^ Joey Roulette, Marisa Taylor (March 16, 2024). "Exclusive: Musk's SpaceX is building spy satellite network for US intelligence agency, sources say". Reuters. Retrieved March 16, 2024.

- ^ FitzGerald, Micah Maidenberg and Drew. "WSJ News Exclusive | Musk's SpaceX Forges Tighter Links With U.S. Spy and Military Agencies". WSJ. Retrieved 2024-03-16.

- ^ "Department of Defense Directive 5105.23, Change 1, 29 October, 2015" (PDF). Department of Defense. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- ^ NRO Organization

- ^ "TacDSR".

- ^ "NRO Factsheet". p. 1. Archived from the original (Word Document) on 2006-12-11. Retrieved 2007-01-15.

- ^ a b Bruce Carlson (2010-09-13). "National Reconnaissance Office Update" (PDF). Air & Space Conference and Technology Exposition 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-12-06. Retrieved 2010-11-25.

- ^ Tim Weiner (1994-08-09). "Ultra-Secret Office Gets First Budget Scrutiny". New York Times. Archived from the original on 2013-01-30. Retrieved 2010-12-22.

- ^ Dilanian, Ken (2010-10-28). "Overall U.S. intelligence budget tops $80 billion". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2011-01-08.

- ^ "Media Roundtable with U.S. Space Command Commander Gen. John Raymond". defense.gov. United States Department of Defense. Retrieved July 21, 2021.

- ^ Browne, Ryan (December 21, 2019). "With a signature, Trump brings Space Force into being". CNN. Retrieved July 21, 2021.

- ^ a b Tadjdeh, Yasmin (July 20, 2021). "JUST IN: National Reconnaissance Office Embracing Commercial Tech". National Defense Magazine. Retrieved July 21, 2021.

- ^ a b McCall, Stephen (December 30, 2020). "Defense Primer: National Security Space Launch" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. Retrieved July 21, 2021.

- ^ "NRO Innovating Faster in Era of Great Power Space Competition". 31 August 2021.

- ^ Boyle, Rebecca (June 5, 2012). "NASA Adopts Two Spare Spy Telescopes, Each Maybe More Powerful than Hubble". Popular Science. Popular Science Technology Group. Retrieved June 5, 2012.

- ^ "2009 National Intelligence / A Consumer's Guide" (PDF). Office of the Director of National Intelligence. 2009. Retrieved 2013-08-19. (page 74)

- ^ a b Scoles, Sarah (2019-07-31). "Meet the US's spy system of the future — it's Sentient". The Verge. Archived from the original on 2019-08-01. Retrieved 2024-02-07.

- ^ "Sentient Program" (PDF). National Reconnaissance Office, Federal government of the United States. 2012-02-13. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-08-08. Retrieved 2024-02-07.

- ^ "SENTIENT Challenge Themes" (PDF). National Reconnaissance Office, Federal government of the United States. 2019-02-09. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-08-01. Retrieved 2024-02-07.

- ^ Cardillo, Robert (2017-03-16). "How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love our Crowded Skies". The Cipher Brief. Archived from the original on 2019-05-15. Retrieved 2024-02-07.

- ^ "NRO Systems Overview - Module 2: Orbital Mechanics" (PDF). National Reconnaissance Office. 13 February 2012. Retrieved 2018-10-11.

- ^ a b c d e f g Clapper, James R. (February 2012). "FY 2013 Congressional Budget Justification, Volume 1, National Intelligence Program Summary, Resource Exhibit No. 13" (PDF). DNI.

- ^ Center for the Study of National Reconnaissance: Bulletin, Combined 2002 Issue: "Declassification of Early Satellite Reconnaissance Film"

- ^ Dr. Bruce Berkowitz (September 2011). "The National Reconnaissance Office At 50 Years: A Brief History" (PDF). Center for the Study of National Reconnaissance. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-10-15. Retrieved 2011-10-24.

- ^ "PARCAE America's Ears in Space" (PDF). NRO.

- ^ [1] Archived July 7, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Mission Ground Station Declassification memo, 2008

- ^ "NRO Mission Ground Station Declassification" (PDF). National Reconnaissance Office. 2008-10-15.

- ^ "Who_We_Are".

External links

[edit]- NRO official website

- Space-Based Reconnaissance by MAJ Robert A. Guerriero

- National Security Archive: The NRO Declassified

- Memo of Declassification of NRO

- Additional NRO information from the Federation of American Scientists

- America's secret spy satellites are costing you billions, but they can't even get off the launch pad at the Wayback Machine (archived November 28, 2007) U.S. News & World Report, 8/11/03; By Douglas Pasternak

- Agency planned exercise on September 11 built around a plane crashing into a building, from Boston.com

- History of the US high-altitude SIGINT system

- History of the US reconnaissance system: imagery