Sling (weapon)

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2013) |

A sling is a projectile weapon typically used to hand-throw a blunt projectile such as a stone, clay, or lead "sling-bullet". It is also known as the shepherd's sling or slingshot (in British English, although elsewhere it means something else).[1] Someone who specializes in using slings is called a slinger.

A sling has a small cradle or pouch in the middle of two retention cords, where a projectile is placed. There is a loop on the end of one side of the retention cords. Depending on the design of the sling, either the middle finger or the wrist is placed through a loop on the end of one cord, and a tab at the end of the other cord is placed between the thumb and forefinger. The sling is swung in an arc, and the tab released at a precise moment. This action releases the projectile to fly inertially and ballistically towards the target. By its double-pendulum kinetics, the sling enables stones (or spears) to be thrown much further than they could be by hand alone.

The sling is inexpensive and easy to build. Historically it has been used for hunting game and in combat. Today the sling is of interest as a wilderness survival tool and an improvised weapon.[2]

The sling in antiquity

[edit]Origins

[edit]The sling is an ancient weapon known to Neolithic peoples around the Mediterranean, but is likely to be much older. It is possible that the sling was invented during the Upper Palaeolithic at a time when new technologies such as the spear-thrower and the bow and arrow were beginning to emerge.[citation needed]

Archaeology

[edit]

Whereas stones and clay objects thought by many archaeologists to be sling-bullets are common finds in the archaeological record,[3] slings themselves are rare. This is both because a sling's materials are biodegradable and because slings were lower-status weapons, rarely preserved in a wealthy person's grave.

The oldest-known surviving slings—radiocarbon dated to c. 2500 BC—were recovered from South American archaeological sites on the coast of Peru. The oldest-known surviving North American sling—radiocarbon dated to c. 1200 BC—was recovered from Lovelock Cave, Nevada.[4][5]

The oldest known extant slings from the Old World were found in the tomb of Tutankhamun, who died c. 1325 BC. A pair of finely plaited slings were found with other weapons. The sling was probably intended for the departed pharaoh to use for hunting game.[6][7]

Another Egyptian sling was excavated in El-Lahun in Al Fayyum Egypt in 1914 by William Matthew Flinders Petrie, and is now in the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology—Petrie dated it to c. 800 BC. It was found alongside an iron spearhead. The remains are broken into three sections. Although fragile, the construction is clear: it is made of bast fibre (almost certainly flax) twine; the cords are braided in a 10-strand elliptical sennit and the cradle seems to have been woven from the same lengths of twine used to form the cords.[8]

Ancient representations

[edit]Representations of slingers can be found on artifacts from all over the ancient world, including Assyrian and Egyptian reliefs, the columns of Trajan[9] and Marcus Aurelius, on coins, and on the Bayeux Tapestry.

The oldest representation of a slinger in art may be from Çatalhöyük, from c. 7,000 BC, though it is the only such depiction at the site, despite numerous depictions of archers.[10]

Written history

[edit]

Many European, Middle Eastern, Asian, and African peoples were users of slings.[12] Thucydides and others authors talk about its usage by Greeks and Romans, and Strabo also extends it to the Iberians, Lusitanians and even some Gauls (which Caesar describes further in his account of the siege of Bibrax). He also mentions Persians and Arabs among those who used them. For his part, Diodorus includes Libyans and Phoenicians.[12] Britons were frequent users of slings too.[13]

Livy mentions some of the most famous of ancient sling experts: the people of the Balearic Islands, who often worked as mercenaries. Of Balearic slingers Strabo writes: "And their training in the use of slings used to be such, from childhood up, that they would not so much as give bread to their children unless they first hit it with the sling."[14]

Classical accounts

[edit]The sling is mentioned as early as in the writings of Homer,[15] where several characters kill enemies by hurling stones at them.[12]

Balearic slingers were amongst the specialist mercenaries extensively employed by Carthage against the Romans and other enemies. These light troops used three sizes of sling, according to the distance of their opponents. The weapons were made of vegetable fibre and animal sinew, launching either stones or lead missiles with devastating impact.[16]

Xenophon in his history of the retreat of the Ten Thousand, 401 BC, relates that the Greeks suffered severely from the slingers in the army of Artaxerxes II of Persia, while they themselves had neither cavalry nor slingers, and were unable to reach the enemy with their arrows and javelins. This deficiency was rectified when a company of 200 Rhodians, who understood the use of leaden sling-bullets, was formed. They were able, says Xenophon, to project their missiles twice as far as the Persian slingers, who used large stones.[17]

Various Greeks enjoyed a reputation for skill with the sling. Thucydides mentions the Acarnanians and Livy refers to the inhabitants of three Greek cities on the northern coast of the Peloponnesus as expert slingers.

Greek armies would also use mounted slingers (ἀκροβολισταί).[18]

Roman skirmishers armed with slings and javelins were established by Servius Tullius.[12][19] The late Roman writer Vegetius, in his work De Re Militari, wrote:

Recruits are to be taught the art of throwing stones both with the hand and sling. The inhabitants of the Balearic Islands are said to have been the inventors of slings, and to have managed them with surprising dexterity, owing to the manner of bringing up their children. The children were not allowed to have their food by their mothers till they had first struck it with their sling. Soldiers, notwithstanding their defensive armour, are often more annoyed by the round stones from the sling than by all the arrows of the enemy. Stones kill without mangling the body, and the contusion is mortal without loss of blood. It is universally known the ancients employed slingers in all their engagements. There is the greater reason for instructing all troops, without exception, in this exercise, as the sling cannot be reckoned any encumbrance, and often is of the greatest service, especially when they are obliged to engage in stony places, to defend a mountain or an eminence, or to repulse an enemy at the attack of a castle or city.[20]

Biblical accounts

[edit]The sling is mentioned in the Bible, which provides what is believed to be the oldest textual reference to a sling in the Book of Judges, 20:16. This text was thought to have been written c. 6th century BC,[21] but refers to events several centuries earlier.

The Bible provides a famous slinger account, the battle between David and Goliath from the First Book of Samuel 17:34–36, probably written in the 7th or 6th century BC, describing events that might have occurred c. 10th century BC. The sling, easily produced, was the weapon of choice for shepherds fending off animals. Due to this, the sling was a commonly used weapon by the Israelite militia.[22] Goliath was a tall, well equipped and experienced warrior. In this account, the shepherd David persuades Saul to let him fight Goliath on behalf of the Israelites. Unarmoured and equipped only with a sling, five smooth rocks, and his staff, David defeats the champion Goliath with a well-aimed shot to the head.

Use of the sling is also mentioned in Second Kings 3:25, First Chronicles 12:2, and Second Chronicles 26:14 to further illustrate Israelite use.

Combat

[edit]

Ancient peoples used the sling in combat—armies included both specialist slingers and regular soldiers equipped with slings. As a weapon, the sling had several advantages; a sling bullet lobbed in a high trajectory can achieve ranges in excess of 400 m (1,300 ft).[23] Modern authorities vary widely in their estimates of the effective range of ancient weapons. A bow and arrow could also have been used to produce a long range arcing trajectory, but ancient writers repeatedly stress the sling's advantage of range. The sling was light to carry and cheap to produce; ammunition in the form of stones was readily available and often to be found near the site of battle. The ranges the sling could achieve with moulded lead sling-bullets was surpassed only by the strong composite bow.

Caches of sling ammunition have been found at the sites of Iron Age hill forts of Europe; some 22,000 sling stones were found at Maiden Castle, Dorset.[24] It is proposed that Iron Age hill forts of Europe were designed to maximize the effective defence by slingers.

The hilltop location of the wooden forts would have given the defending slingers the advantage of range over the attackers, and multiple concentric ramparts, each higher than the other, would allow a large number of men to create a hailstorm of stone. Consistent with this, it has been noted that defences are generally narrow where the natural slope is steep, and wider where the slope is more gradual.

Construction

[edit]A classic sling is braided from non-elastic material. The traditional materials are flax, hemp or wool. Slings by Balearic islanders were said to be made from a rush. Flax and hemp resist rotting, but wool is softer and more comfortable. Polyester is often used for modern slings, because it does not rot or stretch and is soft and free of splinters.

Braided cords are used in preference to twisted rope, as a braid resists twisting when stretched. This improves accuracy.[25]

The overall length of a sling can vary. A slinger may have slings of different lengths. A longer sling is used when greater range is required. A length of about 61 to 100 cm (2.0 to 3.3 ft) is typical.

At the centre of the sling, a cradle or pouch is constructed. This may be formed by making a wide braid from the same material as the cords or by inserting a piece of a different material such as leather. The cradle is typically diamond shaped (although some take the form of a net), and will fold around the projectile in use. Some cradles have a hole or slit that allows the material to wrap around the projectile slightly, thereby holding it more securely.

At the end of one cord (called the retention cord) a finger-loop is formed. At the end of the other cord (the release cord), it is a common practice to form a knot or a tab. The release cord will be held between finger and thumb to be released at just the right moment, and may have a complex braid to add bulk to the end. This makes the knot easier to hold, and the extra weight allows the loose end of a discharged sling to be recovered with a flick of the wrist.[26]

Braided construction resists stretching, and therefore produces an accurate sling. Modern slings are begun by plaiting the cord for the finger loop in the centre of a double-length set of cords. The cords are then folded to form the finger-loop. The retained cord is then plaited away from the loop as a single cord up to the pocket. The pocket is then plaited, most simply as another pair of cords, or with flat braids or a woven net. The remainder of the sling, the released cord, is plaited as a single cord, and then finished with a knot or plaited tab.

Impact

[edit]Ancient poets wrote that sling-bullets could penetrate armour, and that lead projectiles, heated by their passage through the air, would melt in flight.[27][28] In the first instance, it seems likely that the authors were indicating that slings could cause injury through armour by a percussive effect (i.e., the energy of a sling-bullet delivered at high velocity causing blunt trauma injury upon impact) rather than by penetration. In the latter case, it has been proposed that they were impressed by the degree of deformation suffered by lead sling-bullet after hitting a hard target.[29]

According to description of Procopius, the sling had an effective range further than a Hun bow and arrow. In his book Wars of Justinian, he recorded the felling of a Hun warrior by a slinger:

Now one of the Huns who was fighting before the others was making more trouble for the Romans than all the rest. And some rustic made a good shot and hit him on the right knee with a sling, and he immediately fell headlong from his horse to the ground, which thing heartened the Romans still more.[30]

Ammunition

[edit]

The simplest projectile was a stone, preferably well-rounded. Suitable ammunition is frequently from a river or a beach. The size of the projectiles can vary dramatically, from pebbles massing no more than 50 g (1.8 oz) to fist-sized stones massing 500 g (18 oz) or more. The use of such stones as projectiles is well attested in the ethnographic record.[3]

Possible projectiles were also purpose-made from clay; this allowed a very high consistency of size and shape to aid range and accuracy. Many examples have been found in the archaeological record.

The best ammunition was cast from lead. Leaden sling-bullets were widely used in the Greek and Roman world. For a given mass, lead, being very dense, offers the minimum size and therefore minimum air resistance. In addition, leaden sling-bullets are small and difficult to see in flight; their concentrated impact is also a better armour-piercer and better able to penetrate a body.

In some cases, the lead would be cast in a simple open mould made by pushing a finger or thumb into sand and pouring molten metal into the hole. However, sling-bullets were more frequently cast in two-part moulds. Such sling-bullets come in a number of shapes including an ellipsoidal form closely resembling an acorn; this could be the origin of the Latin word for a leaden sling-bullet: glandes plumbeae (literally 'leaden acorns') or simply glandes (meaning 'acorns', singular glans).

Other shapes include spherical and (by far the most common) biconical, which resembles the shape of the shell of an almond nut or a flattened American football.

The ancients do not seem to have taken advantage of the manufacturing process to produce consistent results; leaden sling-bullets vary significantly. The reason why the almond shape was favoured is not clear: it is possible that there is some aerodynamic advantage, but it seems equally likely that there is some more prosaic reason, such as the shape being easy to extract from a mould, or the fact that it will rest in a sling cradle with little danger of rolling out. It is possible as well that the almond, non-circular shape made the bullet spin in flight in a helicopter or disc like effect adding to the flight distance.

Almond-shaped leaden sling-bullets were typically 35 mm (1.4 in) long, 20 mm (0.79 in) wide, and weighs 28 g (0.99 oz). Very often, symbols or writings were moulded into lead sling-bullets. Many examples have been found including a collection of about 80 sling-bullets from the siege of Perusia in Etruria from 41 BC, to be found in the museum of modern Perugia. Examples of symbols include a stylized lightning bolt, a snake, and a scorpion – reminders of how a sling might strike without warning. Writing might include the name of the owning military unit or commander or might be more imaginative: "Take this", "Ouch", "get pregnant with this"[31] and even "For Pompey's backside" added insult to injury, whereas dexai ('take this' or 'catch!')[11] is merely sarcastic. In Yavne, a sling bullet with the Greek inscription "Victory of Heracles and Hauronas" was discovered, the two gods were the patrons of the city during the Hellenistic period.[32]

Julius Caesar writes in De bello Gallico, book 5, about clay shot being heated before slinging, so that it might set fire to thatch.[33]

"Whistling" bullets

[edit]Some bullets have been found with holes drilled in them. It was thought the holes were to contain poison. John Reid of the Trimontium Trust, finding holed Roman bullets excavated at the Burnswark hillfort, has proposed that the holes would cause the bullets to "whistle" in flight and the sound would intimidate opponents. The holed bullets were generally small and thus not particularly dangerous. Several could fit into a pouch and a single slinger could produce a terrorizing barrage. Experiments with modern copies demonstrate they produce a whooshing sound in flight.[34]

The sling in medieval period

[edit]Europe

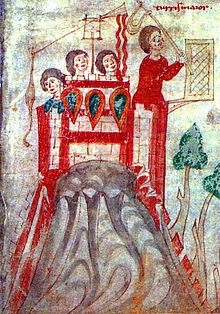

[edit]The Bayeux Tapestry of the 1070s portrays the use of slings in a hunting context. Frederick I, Holy Roman Emperor employed slingers during the Siege of Tortona in 1155 to suppress the garrison while his own men built siege engines.[35] Indeed, slings seem to have been a fairly common weapon in Italy during the 11th and 12th centuries.[36] Slings were also used by the Byzantines.[37] On the Iberian Peninsula, the Spanish and Portuguese infantry favoured it against light and agile Moorish troops. The staff sling continued to be used in sieges and the sling was used as a part of large siege engines.[38]

The Americas

[edit]

The sling was known throughout the Americas.[39]

In ancient Andean civilizations such as the Inca Empire, slings were made from llama wool. These slings typically have a cradle that is long and thin and features a relatively long slit. Andean slings were constructed from contrasting colours of wool; complex braids and fine workmanship can result in beautiful patterns. Ceremonial slings were also made; these were large, non-functional and generally lacked a slit. To this day, ceremonial slings are used in parts of the Andes as accessories in dances and in mock battles. They are also used by llama herders; the animals will move away from the sound of a stone landing. The stones are not slung to hit the animals, but to persuade them to move in the desired direction.

The sling was also used in the Americas for hunting and warfare. One notable use was in Incan resistance against the conquistadors. These slings were apparently very powerful; in 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus, author Charles C. Mann quoted a conquistador as saying that an Incan sling "could break a sword in two pieces" and "kill a horse".[40] Some slings spanned as much as 2.2 meters (86 in) long and weighed an impressive 410 grams (14.4 oz).[41][42]

Guam

[edit]Unique amongst most Pacific Islanders, the Chamorro reached a terrific competency with a weapon as witness by 17th century Belgian missionary, Pedro Coomans:

"Their offensive weapons include the sling, which they aim very skillfully at the head. Out of small ropes they weave a sort of net-bag, in which to carry stones with an oblong shape, some formed out of a marble stone, and others of clay, hardened in either the sun or fire. They whirl and shoot those so violently. Should it make an impact upon a more delicate part, like the heart, or the head, the man is flattened on the spot. Then, if envy would make them want to burn a house from a distance, they would stuff the perforated side of it with tow burning with a very ferocious fire, which, with a swift movement became a flame, and sail away to seek shelter in enemy houses."[43]

The sling stone (in its "almond"/ovoid shape) is a vital cultural artifact of Chamorro culture, enough so, that it was adopted for the Guamian flag and state seal.[43]

Variants

[edit]

Staff sling

[edit]The staff sling, also known as the stave sling, fustibalus (Latin), and fustibale (French), consists of a staff (a length of wood) with a short sling at one end. One cord of the sling is firmly attached to the stave and the other end has a loop that can slide off and release the projectile. Staff slings are extremely powerful because the stave can be made as long as two meters, creating a powerful lever. Ancient art shows slingers holding staff slings by one end, with the pocket behind them, and using both hands to throw the staves forward over their heads.

The staff sling has a similar or superior range to the shepherd's sling, and can be as accurate in practiced hands. It is generally suited for heavier missiles and siege situations as staff slings can achieve very steep trajectories for slinging over obstacles such as castle walls. The staff itself can become a close combat weapon in a melee. The staff sling is able to throw heavy projectiles a much greater distance and at a higher arc than a hand sling. Staff slings were in use well into the age of gunpowder as grenade launchers, and were used in ship-to-ship combat to throw incendiaries.[citation needed]

Piao Shi (whirlwind stone)

[edit]Piao Shi (飃石, lit. 'whirlwind stone'), also known as Shou Pao (手砲, lit. hand cannon) during the Song period, is the Chinese name for staff sling. It consists of a short cord tied to one end of a five chi bamboo pole, and is usually employed in siege defense alongside larger stone throwers. It is depicted and described in the Ji Xiao Xin Shu (紀效新書).

Kestros

[edit]The kestros (also known as the kestrosphendone, cestrus, or cestrosphendone) is a sling weapon mentioned by Livy and Polybius. It seems to have been a heavy dart flung from a leather sling. It was invented in 168 BC and was employed by some of the Macedonian troops of King Perseus in the Third Macedonian war.

Siege engines

[edit]The traction trebuchet was a siege engine which uses the power of men pulling on ropes or the energy stored in a raised weight to rotate what was, again, a staff sling. It was designed so that, when the throwing arm of the trebuchet had swung forward sufficiently, one end of the sling would automatically become detached and release the projectile. Some trebuchets were small and operated by a very small crew; however, unlike the onager, it was possible to build the trebuchet on a gigantic scale: such giants could hurl enormous rocks at huge ranges. Trebuchets are, in essence, mechanized slings.

Hand-trebuchet

[edit]The hand-trebuchet (Greek: χειρομάγγανον, cheiromanganon) was a staff sling mounted on a pole using a lever mechanism to propel projectiles.

Today

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2023) |

Traditional slinging is still practiced as it always has been in the Balearic Islands,[citation needed] and competitions and leagues are common. In the rest of the world, the sling is primarily a hobby weapon, and a growing number of people make and practice with them. In recent years 'slingfests' have been held in Wyoming, USA, in September 2007 and in Staffordshire, England, in June 2008.[citation needed]

According to Guinness World Records, the current record for the greatest distance achieved in hurling an object from a sling is 477.10 m (1,565 ft 3 in), using a 127 cm (50 in) long sling and a 62 g (2.2 oz) dart, set by David Engvall at Baldwin Lake, California, on September 13, 1992.[44]

The principles of the sling may find use on a larger scale in the future; proposals exist for tether propulsion of spacecraft, which functionally is an oversized sling to propel a spaceship.

The sling is used today as a weapon primarily by protestors, to launch either stones or incendiary devices, such as Molotov cocktails. Classic woolen slings are still in use in the Middle East by Arab nomads and Bedouins to ward off jackals and hyenas. International Brigades used slings to throw grenades during the Spanish Civil War. Similarly, the Finns made use of sling-launched Molotov cocktails in the Winter War against Soviet tanks. Slings were used during the various Palestinian riots against modern army personnel and riot police. They were also used in the 2008 disturbances in Kenya.[45][46]

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ "Slingshot definition and meaning". Collins Dictionary. Retrieved 5 May 2022.

- ^ Savage, Cliff (2011). The Sling for Sport and Survival. Boulder, Colorado: Paladin Press. pp. 60–61. ISBN 978-1-58160-565-5.

- ^ a b Seager Thomas, Mike (2013). Reassessing Slingstones. Artefact Services Research Papers 3. Lewes: Artefact Services.

- ^ Makiko Tada. "A History of Sling Braiding in the Andes".

- ^ York, Robert; York, Gigi (2011). Slings & Slingstones. Kent State U. Press. pp. 76, 96, 122. ISBN 978-1-60635-107-9.

- ^ "Image of sling from the Tomb of Tutankhamen". Archived from the original on 3 April 2006.

- ^ "Griffith Institute: Carter Archives - p1324". www.griffith.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ^ "Other uses of textile in ancient Egypt". www.ucl.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 10 December 2006.

- ^ William Smith, LLD. William Wayte. G. E. Marindin (1890). "Image "Soldier with sling. (From the Column of Trajan)"". A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities. London: John Murray.

- ^ "Project Goliath | Main / UpperPaleolithicNeolithic". slinging.org.

- ^ a b "Lead sling bullet; almond shape; a winged thunderbolt on one side and on the other, in high relief, the inscription DEXAI "Catch!"". Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- ^ a b c d Pritchett, W. Kendrick (1974). The Greek State at War: Part V. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520073746.

- ^ Swan, David (2014). "Attitudes Towards and Use of the Sling in Late Iron Age Britain". Reinvention: An International Journal of Undergraduate Research. 7 (2). Archived from the original on 5 November 2022. Retrieved 31 December 2020.

- ^ "LacusCurtius • Strabo's Geography — Book III Chapter 5". Penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 12 September 2010.

- ^ "The Iliad of Homer, translated by Cowper". Gutenberg.org. 5 August 2005. Retrieved 12 September 2010.

- ^ Salimbeti, Andre (22 April 2014). The Carthaginians. Bloomsbury USA. p. 41. ISBN 978-1-78200-776-0.

- ^ "Xenophon, Anabasis, chapter III". Gutenberg.org. 1 January 1998. Retrieved 12 September 2010.

- ^ Thomas Dudley Fosbroke, A Treatise on the Arts, Manufactures, Manners, and Institutions of the Greek and Romans, Volumen 2, 1835

- ^ "DBM - Tullian Roman".

- ^ "Digital | Attic – Warfare: De Re Militari Book I: The Selection and Training of New Levies". Pvv.ntnu.no. Archived from the original on 16 July 2012. Retrieved 12 September 2010.

- ^ Knoppers, Gary, "Is There a Future for the Deuteronomistic History?", In Thomas Romer, The Future of the Deuteronomistic History, Leuven University Press, 2000 ISBN 978-90-429-0858-1, p. 119.

- ^ Yigael Yadin, The Art of Warfare in Biblical Lands (Jerusalem: International Publishing Company, 1963), 34–35

- ^ Harrison, Chris (Spring 2006). "The Sling in Medieval Europe". The Bulletin of Primitive Technology. 31.

- ^ Cunliffe, Barry (2005). Iron Age Communities in Britain: An Account of England, Scotland and Wales from the Seventh Century BC until the Roman Conquest (4th ed.). Routledge. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-415-56292-8.

- ^ Cahlander, Adele (1980). Sling Braiding of the Andes (Weaver's Journal Monograph IV). St. Paul, MN: Dos Tejadores. ISBN 978-0937452035.

- ^ Ramsey, Syed (2016). Tools of War: History of Weapons in Medieval Times. Alpha Editions. p. 147. ISBN 978-9386101662. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- ^ Lucretius, On the Nature of Things-- "Just as thou seest how motion will o'erheat / And set ablaze all objects, - verily / A leaden ball, hurtling through length of space, / Even melts."

- ^ Virgil, The Aeneid, Book 9, Stanza LXXV – "His lance laid by, thrice whirling round his head / The whistling thong, Mezentius took his aim. / Clean through his temples hissed the molten lead, / And prostrate in the dust, the gallant youth lay dead."

- ^ Pritchett, W. Kendrick (1992). The Greek State at War: Part V. University of California Press. pp. 24–25, footnote 44. ISBN 978-0-520-07374-6.

- ^ Procopius, Persian war

- ^ Fields, Nic (20 May 2008). Syracuse 415-413 BC. Bloomsbury USA. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-84603-258-5.

- ^ "i24NEWS". www.i24news.tv. 8 December 2022.

- ^ Caesar Bell. Gall. 5,43,1.

- ^ "Bullets, ballistas, and Burnswark – A Roman assault on a hillfort in Scotland". Current Archeology. 1 June 2016.

- ^ Bradbury 1992, p. 89.

- ^ Brown, Paul (2016). Norman Warfare in the Eleventh and Twelfth-Century Mediterranean.

- ^ Haldon, John F. (1999): "Warfare, State and Society in the Byzantine World, 565-1204, p. 216

- ^ Bradbury 1992, p. 262.

- ^ Paul Campbell. "The Chumash Sling". ABOtech.com. Archived from the original on 8 June 2007. Retrieved 16 May 2007.

- ^ Mann, pg. 84.

- ^ "Slings from Peru and Bolivia". Flight-toys.com. 18 February 2010. Retrieved 12 September 2010.

- ^ Jane Penrose (10 October 2005). Slings in the Iron Age. Bloomsbury USA. ISBN 9781841769325. Retrieved 30 June 2010.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b "» Slingstones". 29 September 2009.

- ^ "Longest sling shot". Retrieved 25 October 2023.

- ^ "Ethnic Clashes in Kenya". New York Times. 3 February 2008.

- ^ Jeffrey Gettleman (1 February 2008). "Second Lawmaker Is Killed as Kenya's Riots Intensify". New York Times.

Further reading

[edit]- Bradbury, Jim (1992). The Medieval Siege. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0851153575.

- Burgess, E. Martin (June 1958). "An Ancient Egyptian Sling Reconstructed". Journal of the Arms and Armour Society. 2 (10): 226–30.

- Dohrenwend, Robert (2002). "The Sling. Forgotten Firepower of Antiquity" (PDF). Journal of Asian Martial Arts. 11 (2): 28–49.

- Richardson, Thom, "The Ballistics of the Sling", Royal Armouries Yearbook, Vol. 3 (1998)

- York, Robert & Gigi, "Slings and Slingstones, The Forgotten Weapons of Oceania and the Americas", The Kent State University Press (2011)

External links

[edit]- Slinging.org resources for slinging enthusiasts.

- Sling Weapons The Evolution of Sling Weapons

- The Sling – Ancient Weapon

- Sports and Pastimes of the People of England, Joseph Strutt, 1903.

- Funda, William Smith, A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities.