Franks

The Franks (Latin: Franci or gens Francorum; German: Franken; French: Francs) were a group of several related Germanic peoples who originally inhabited the northern and eastern banks of the fortified Roman border (Limes) along the northernmost stretches of the river Rhine. The Romans only began to refer to these tribes as Franks in the third century AD. In the fourth century the Roman also began to distinguish tribes further north with another new collective term "Saxons", although there are signs that the terms Frank, Saxon were not always mutually exclusive in the earliest period. The Franks lived for centuries under Roman hegemony, as the long-term neighbours of Germania Inferior, which was the most northerly Roman province in continental Europe, and contained much of what is now the Netherlands, the German Rhineland, and Belgium. Over centuries, the Romans recruited large numbers of Frankish soldiers, some of whom achieved high imperial rank.

Many Franks were already living within the empire in the early fifth century, when Roman power broke down for the last time in northern Gaul, and large numbers of Eastern European peoples penetrated Rome's European border regions. In about 406 AD Franks attempted to defend the Roman border when it was crossed by Alans and Vandals, but they failed. Frankish kings subsequently divided up Germania Inferior between them and at least one, Chlodio, began to rule more Romanized populations to the south. In 451 AD Frankish groups participated on both sides in the Battle of the Catalaunian Plains, where Attila and his allies were defeated by a Roman-led alliance of most of the various peoples who now lived in Gaul. By the early 6th century the whole of Gaul north of the Loire, and all the Frankish kingdoms, were united within the kingdom of the Frank Clovis I, the founder of the Merovingian dynasty. By building upon the basis of this empire the subsequent dynasty, the Carolingians, eventually came to be seen as the new emperors of Western Europe in 800, when Charlemagne was crowned by the pope.

Within the former Roman empire, the Franks became a multilingual, Catholic people who subsequently came to rule over several other post-Roman kingdoms both inside and outside the old empire. As the original Frankish communities merged into others, the term "Frank" lost its original meaning. In 870, the Frankish realm was permanently divided between western and eastern kingdoms, which were the predecessors of the later Kingdom of France and Holy Roman Empire respectively. In the European languages of the time, the Latin term Franci came to refer mainly to the people of the Kingdom of France, the forerunner of present day France. In a broader sense much of the population of western Europe could sometimes be described as Franks. In various historical contexts, such as during the medieval crusades, not only the French, but also people from neighbouring regions in Western Europe, continued to be referred to collectively as Franks. The crusaders in particular had a lasting impact on the use of Frank-related names which are used for all Western Europeans in many non-European languages.

Name of the Franks

[edit]The origins of the term Franci are unclear, but by the 4th century it was commonly used as a collective term to refer to several tribes who were also known to the Romans by their own tribal names, or under the older but much broader collective name Germani, which also covered many non-Frankish peoples such as the Alemanni or Marcomanni. Within a few centuries the term had eclipsed the names of the original peoples who constituted the Frankish population.

After their conquest of Romanized Gaul, many Germanic-speaking Franks lived in communities where most people were not Frankish, or Frankish speaking. However, as the Franks became more powerful, and more integrated with the peoples they ruled over, the name came to be more broadly applied, especially in what is now northern France. Christopher Wickham pointed out that "the word 'Frankish' quickly ceased to have an exclusive ethnic connotation. North of the River Loire everyone seems to have been considered a Frank by the mid-7th century at the latest (except Bretons); Romani (Romans) were essentially the inhabitants of Aquitaine after that".[1]

The original meaning of the word is unclear, although it is commonly believed to have a Germanic etymology.[2] Following the precedents of Edward Gibbon and Jacob Grimm,[3] the name of the Franks was traditionally linked with the English adjective frank, meaning "free", which came from Old French franc. This term is however derived from the term Frank itself, as it referred to their free status.[4] Similarly the word has been connected to a Germanic word for "javelin", reflected in words such as Old English franca or Old Norse frakka, but these terms possibly also derive from the name of the Franks, as the name of a Frankish weapon. (Alternatively, this Germanic word may derive from Latin framea, which was the word Romans used to describe the javelin used by Germani.)[5]

A common proposal to explain the ultimate origin of all these terms is that it meant "fierce".[2] A proto-Germanic word has been reconstructed, *frekaz, which meant "greedy", but sometimes tended towards meanings such as "bold".[5][4] It has descendants such as German frech (cheeky, shameless), Middle Dutch vrec (miserly), Old English frǣc (greedy, bold), and Old Norse frekr (brazen, greedy).

The idea that the name of the Franks meant fierce is partly derived from classical allusions to their ferocity and unreliability as defining traits. For example, Eumenius rhetorically addressed the Franks when Frankish prisoners were executed in the area at Trier by Constantine I in 306: Ubi nunc est illa ferocia? Ubi semper infida mobilitas? ("Where now is that ferocity of yours? Where is that ever untrustworthy fickleness?").[6] Isidore of Seville (died 636) said that there were two proposals known to him. Either the Franks took their name from a war leader who founded them, called Francus, or else their name referred to their wild manners (feritas morum).[7]

As societies changed the name acquired new meanings, and the old Frankish community ceased to exist in its original form. In Europe in later times it was mainly the inhabitants of the Kingdom of France who came to be referred to in Latin as the Franci (Franks), although new terms soon became more common, which connect them to the Franks, but also distinguish them. The modern English word "French" comes from the Old English word for "Frankish", Frencisc. Modern European terms such as French Les Français and German Die Franzosen, derive from Medieval Latin francensis meaning "from Francia", the country of the Franks, which for medieval people was France. In Medieval Latin French people were also commonly referred to as francigenae, or "France-born".

However, in more international contexts such as during the crusades in the Eastern Mediterranean, the term Frank was also used for any Europeans from Western and Central Europe, that followed the Latin rites of Christianity under the authority of the pope in Rome. The use of the term Frank to refer to all western Europeans spread eastwards to many Asian languages.

Mythological origins

[edit]Several accounts from Merovingian times report that some medieval Franks believed that their ancestors originally moved to their Rhineland homeland from Pannonia on the Danube. These include the History of the Franks which was written by Gregory of Tours in the 6th century, a 7th-century work known as the Chronicle of Fredegar, and the anonymous Liber Historiae Francorum, written a century later.[8]

While Gregory did not go deeply into the story, possibly because he rejected it,[9] the other two sources report variants of the idea that, just as in the mythical origin story of the Romans created by Virgil, the Franks descended from Trojan royalty, who escaped from after the Fall of Troy. Fredegar's version, which mentions the poet Virgil by name, connected the Franks not only to the Romans but also to the Phrygians, Macedonians, and Turks. He also reported that they built a new city on the Rhine named Troy after their ancestral home. The city he had in mind is likely to be the real Roman city now known as Xanten, but then known as Colonia Traiana, which was really named after Trajan, but was known as Troja minor (lesser Troy) in the Middle Ages.[10]

The other work, the Liber Historiae Francorum, adds an episode to the story whereby the Pannonian Franks instead founded a city called Sicambria in Pannonia, and while there they fought successfully for a Roman emperor named Valentinian against the Alans, near the Sea of Azov, where the Franks themselves had previously lived.[11] The city name appears to be based upon the Sicambri who were one of the most well-known tribe in the Frankish Rhine homeland in the time of the early Roman empire. According to the story the Franks were forced to leave Pannonia after rebelling against Roman taxes.

In reality, the Franks had been resident in the Rhine for centuries before the Valentinian dynasty confronted the Alans in the late 4th century. It has been suggested that this element in the story may preserve stories from Frankish officers who served the dynasty against the Alans in southeastern Europe, such as Merobaudes.[12] The story might also be influenced by memories of the later Frankish defence of the Roman empire during the subsequent entrance of Alans and other peoples, including many from Pannonia, into Gaul in about 406 AD. Furthermore, the names of Alans and Pannonia, were well-known to later generations of Franks and Romans in northern Gaul, because a kingdom of Alans was founded near Orleans, and Attila's Hun alliance based in Pannonia, invaded Gaul in 451 AD. The name "Sicambria" can be explained as a derivative of the idea found in Graeco-Roman literature, that the Sicambri were ancestors of the later Franks, but in reality they had lived near the Rhine, like the Franks.[13]

On the other hand, concerning the Trojan element in the Frankish origin stories, historian Patrick J. Geary has for example written that they are "alike in betraying both the fact that the Franks knew little about their background and that they may have felt some inferiority in comparison with other peoples of antiquity who possessed an ancient name and glorious tradition."[14]

History

[edit]Early Franks (250-350)

[edit]

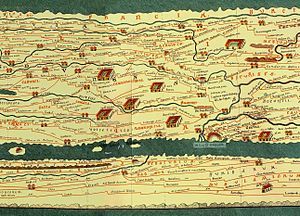

The term "Franks" was first used during the third century AD, perhaps as early as the Crisis of the Third Century (235–284). However, most of the sources which mention Franks in this period were written much later, and their occasional use of the term to describe the 3rd century events is not always conclusive evidence. The older tribes which are most confidently believed to have become Franks by the 4th century include the Chamavi, Bructeri, and Chattuari.[15] The Chamavi are called Franks in the Tabula Peutingeriana,[16] a 13th-century copy of a 4th or 5th century atlas of Roman roads that reflects information from the 3rd century.[17] The Chattuari were described as Franks living across from Xanten in an account of a Roman attack in 360 AD,[18] and the Bructeri were also described as Franks living across from Cologne in an account of a Roman attack in 392/393 AD.[18]

It has been noted by scholars of the earliest records mentioning Franks that there are surprisingly frequent references to them raiding by sea, given the inland position of most of the Frankish tribes, and their later inland status, separated from the sea by the Frisians and Saxons. It appears that in the third and fourth centuries the sea-going Saxons, another new category of people in this period, were not yet clearly distinct from the Franks and Frisians.[19] There are indications that the coastal Frisians who were always distinguished from the Franks in later records, as well as their original eastern neighbours the Chauci, may have contributed to the ethnogenesis of both the Saxons and the Franks. It is even speculated that the so-called Salian Franks, who appear only in records from around 378 AD, may have originally been a Frisian or Chauci tribe.[20]

The earliest mention of Franks in the Augustan History is very uncertain. This is a much-later written collection of biographies of Roman emperors, which modern scholars believe to be largely fabricated. In its biography of the emperor Aurelian (reigned 270-275) it says that before being emperor he was at Mainz as "tribune of the Sixth Legion, the Gallican", a legion known from no other record, when he "crushed the Franks, who had burst into Gaul and were roving about through the whole country". He supposedly killed seven hundred of them and captured three hundred, selling them as slaves, and a song was supposedly composed about him: "Franks, Sarmatians by the thousand, once and once again we've slain. Now we seek a thousand Persians" (Mille Sarmatas, mille Francos semel et semel occidimus, mille Persas quaerimus). While the naming of the Franks within a supposedly popular song may seem unlikely to be fabricated, even this is considered likely by some scholars.[21] If real though, the song would have come into being before 270 AD when Aurelian became emperor, and the events themselves would have been around 245-253 AD.[22]

Other late sources for this period are considered somewhat more reliable. However, most of them did not use the term Frank, but less specific terms such as Germani or "barbarians". Around 256/257 Germani crossed the Rhine and attacked Gaul. Some were Alemanni, who went on to invade Italy from Gaul. By 258/259 other Germani had gotten as far as Tarragona in Spain, and these even acquired ships in Spain with which they attacked North Africa. According to Aurelius Victor writing in the 4th century this latter group were Franks.[23] In the aftermath, Postumus (emperor of the breakaway Gallic Empire 260-268) apparently managed to stabilize the border, and recruited Franks into his army, using them against his rival Gallienus.[24]

Throughout the 260s and 270s very few surviving records explicitly mention the Franks, although the barbarians of the later Frankish region were very active. Gallienus reigned solo from 260 to 268 AD, and during this period the document known as the Laterculus Veronensis, which was made about 314 AD, notes that the Romans lost five civitates (small countries) along the eastern bank of the Lower Rhine. The three which are legible are those of the Usipii, Tubantes, and Chattuari. These probably all became Frankish.[25] During this period, the 260s, archaeologists also note an increase in coin hoards in populations on the Roman side the Rhine, in Tongeren, Amiens, Beauvais, Trier, Metz, Toul, and Chalon-sur-Saône attesting to Frankish activity in this region. Under last Gallic emperor Tetricus (reigned 270–274), there are even more hoard finds, and evidence of military conflicts.[24]

In 275/76, after the death of Tetricus and the reunification of the empire under Probus (reigned 276-282) archaeologists believe that a larger incursion into Gaul occurred, with the main thrust seemingly along the Meuse. In the context of these conflicts, Trier itself fell to an attack. The only involved barbarian group who is named by Roman sources are the Franks, mentioned by Zosimus. Probus subsequently appears to have restabilized the border.[26]

About 280 AD, while Probus was confronted with a rebel named Proculus, the 8th Latin Panegyric, of 297 AD, reports that some captive Franks seized some ships, and "plundered their way from the Black Sea right to Greece and Asia and, driven not without causing damage from very many parts of the Libyan shore, finally took Syracuse itself", and eventually made it back to their homeland via the Ocean.[27][28] In 281 AD Proclus captured and killed Proculus and the Historia Augusta account of this says that it was the Franks who handed him over, because he had fled to them, having Frankish origins himself.[29]

Before 286 AD, Eutropius the historian, writing in the 4th century, and Orosius, writing around 400 AD, reported that emperor Maximian assigned Carausius to lead a naval force to pacify the English channel coasts of Roman Belgica, and Armorica, because these waters were infested by Frankish and Saxon pirates.[30] This is also one of the first uses of the term Saxon, which was subsequently used for seagoing Germanic raiders.

The first contemporary record using the term Frank is the so-called 11th Latin Panegyric written in 291 AD. Taken in combination with the 10th panegyric 289 AD, these records indicate that in the winter of 287/288 Maximian, based in Trier at this time, forced a Frankish king Genobaud and his people to become Roman clients.[31] Probably connected to this, Maximian had recently had at least one successful campaign east of the Rhine. Elsewhere the 11th panegyric also specifically mentions Franks being subdued in this period.[32][33][34]

In 293/294, Constantius Chlorus, son-in-law of Maximian, and father of Constantine I defeated Franks in the Rhine-Meuse-Scheldt delta. Various groups had settled south of the Rhine within the empire, but were living outside of Roman governance while Carausius rebelled. Eumenius mentions Constantius as having "killed, expelled, captured [and] kidnapped" the Franks who had settled there and others who had crossed the Rhine, using the term nationes Franciae for the first time, indicating that the Franks were seen as more than one tribe or nation. The 8th Latin Panegyric written in 297 is commonly interpreted as naming two of the peoples conquered in this campaign as the Chamavi and Frisians, which makes it likely (but not certain) that both these peoples were considered Franks in this period.[35]

In 308 AD, Constantine the Great executed two "kings of Francia", Ascaric and Merogaisus, who violated the peace after the death of his father Constantius, and then "so that the enemy should not merely grieve over the punishment of their kings" made a devastating raid on the Bructeri, and built a bridge over the Rhine at Cologne to "lord it over the remnants of a shattered nation".[36]

In the period 306-319 AD during the reign of Constantine, his panegyrist Nazarius, writing in 321 AD, claims that the Franks "who are more ferocious than other nations", one last time in a seagoing role, "held even the coasts of Spain infested with arms when a large number of them spread abroad beyond the Ocean itself in an outburst of fury in their passion to make war" saying that the Franks are a "nation which is fecund to its own detriment".[37]

In a list of barbarian nations under Roman domination the Laterculus Veronensis, which was made about 314 AD, lists Saxons and Franks separately from several of the older Rhineland tribal names including the Chamavi ("Camari"), Cattuari ("Gallouari") Amsiuari, Angriuari, Bructeri, and Cati.[38]

Archaeological evidence confirms that from around 250 AD there was a massive decrease in population in many parts of Germania Inferior including cities. Several regions around the Rhine-Meuse and Scheldt deltas, remained relatively unpopulated until around 400 AD. Roymans and Heeren proposed that one possible explanation for such a sudden depopulation is that the Roman emperors Maximian and Constantius Chlorus deported very large numbers of locals (and not only immigrants) out of the region. Productive agricultural land was abandoned on a large scale, making the Roman military along the Rhine highly dependent on grain imports from other provinces. Although the Rhine forts did not cease to function completely, the districts around the delta were "dispensed with once and for all as tax-paying administrative units".[39]

Roman texts of the third and fourth centuries describe Franks being settled in many areas of Gaul both as semi-free colonists who had to provide soldiers (laeti) and as conquered dediticii with no rights of citizenship.[citation needed]

Julian the Apostate's campaigns

[edit]In 341 AD the emperor Constans I, one of the sons of Constantine, attacked the Franks in the Rhine delta, and in 342 AD the situation was pacified. Scholars speculate that some Franks were given permission to remain in the area at this time.[40]

In the Spring of 358 AD the Salian Franks were described under that name for the only time in written history, and important new agreements were made between Franks and Romans.[41] Julian the Apostate commanding Roman forces in Gaul, and not yet an emperor, made a rapid attack against both the Salians and the Chamavi, who were both making inroads within Roman territory around the Rhine-Meuse delta. The reason for this was primarily that he needed to ensure the arrival of 600 grain carrying ships coming up the rivers from Britain, and he preferred not to simply pay the tribes off, as previous administrators had been doing.[40] Similar accounts are given by Julian himself in his letter to the Athenians, Ammianus Marcellinus who served under him,[42] Libanius who wrote his funeral oration, and the later Greek historians Eunapius and Zosimus. He first confronted the people who Ammianus called "Franks who are customarily called Salians". Julian says he received the submission of part of the Salian tribe, but does not call them Franks. Zosimus says the Salians were descended from the Franks.

According to Eunapius the Salians were allowed by Julian to holds lands which they had not fought for. Ammianus indicates that they had been settling in Texandria which modern scholars believe was lightly populated. However, Zosimus explains that they had been settled on the large island of Batavia in the delta, until recent raiding by the Saxons who Zosimus called the "Quadi". This island, he said, had once been Roman controlled, but more recently it was Salian held. Zosimus also reports that the Salians had previously lived outside the empire, and had in the past been forced by the Saxons to move to Batavia, within the empire. (Historians speculate that they may have been permitted by the Romans to settle in Texandria since 342.[40])

According to Zosimus the Franks near the delta had been defending the Roman lands against Saxon raids, so that the "Quadi" had been forced to build boats, in which they sailed along the Rhine beyond the territory of the Franks, and entered the Roman empire there. Eunapius says that Julian instructed his men not to hurt the Salians. The people who Zosimus calls Saxons or Quadi are called Chamavi by the other sources. (The Chamavi are treated as Franks in other records, but Zosimus contrasted them with the Franks.) Despite these differences in terminology, Zosimus and Eunapius both remark how the barbarian Charietto was brought from Trier to neutralize this group's raiding, and how Julian captured the son of their king. Julian reported to the Athenians that he subsequently ejected them from lands, and took captives, and cattle. However both Eunapius and Julian make it clear that he also needed an agreement with the Chamavi in order to secure a safe passage for food supplies.

All later references to the Salians as a people, as opposed to the much later legal code, could be connected to these events. The 5th century Notitia Dignitatum mentions three military units whose names include the term "Salii", all three of which were created by Julian, who also created three parallel Tubantes units: the Salii and the Salii seniores, who both belonged to the auxilia palatina, and the Salii (iuniores) Gallicani. However in this period units did not necessary recruit from the barbarian groups they were often named after.[43] The tribe was also mentioned in a poetic way twice by fifth century poets, Claudius Claudianus and Sidonius Apollinaris.[44] According to historian Matthias Springer the evidence suggests that the Salian name was not really their tribal name, but rather a Germanic word meaning something like "comrades". He proposed that the Salians were just called Franks. According to Springer, the Salic law first mentioned centuries later is derived from the same word, but has no specific ethnic connotation, being simply the customary law holding for non-Roman free men.[45]

In 360/361 AD Julian crossed the Rhine near Xanten and defeated the Chattuari, who were described as Franks in records of this event.[18][46]

During the late 360s, after the death of Julian, the "second" Latin Panegyric indicates that Count Theodosius fought won an infantry campaign in Batavia, and perhaps also a naval campaign in the Maas and Waal rivers. The details are not explained in this or any other record, but other records mention that northern Gaul was afflicted by Saxon sea raiders and Frankish land raiders in this period.[47]

The archaeological evidence for the late fourth century suggestions that the population remained low in the northern part of Roman Lower Germany until almost 400 AD.[48]

Arbogast's campaigns

[edit]During the reigns of Emperors of the Valentinian dynasty four franks served as magistri militum (commanders-in-chief of the imperial army):[49]

- Merobaudes (372–383, under Valentinian I and Gratian in Trier)

- Ricomer (382–394, under Theodosius the Great in Constantinople)

- Bauto (383–387/88, under Valentinian II in Milan)

- Arbogast (388–394, under Valentinian II and Eugenius in Trier).

In 388 AD, the year after the Gaulish usurper Magnus Maximus left his base at Trier, Franks under the command of three war leaders, Marcomer, Sunno and Genobaud, crossed the Rhine and raided deep into the empire. Some returned over the Rhine successfully with their plunder while others entered the Silva Carbonaria, a forest in present day Belgium, where they were tracked down by Roman forces. Roman forces that tried to pursue the Franks over the Rhine were cut to pieces. After the death of Maximus, Arbogast urged action. He met Marcomer and Sunno and demanded hostages, and then based himself in Trier. After the death of Valentinian II, Arbogast took advantage of the leaves falling, and went to Cologne and crossed into the country of the Bructeri, and plundered it, and also the region inhabited by the Chamavi. The Franks did not engage with him although some Ampsivarii and Chatti under the command of Marcomer appeared on the ridge of a distant hill. By this time Arbogast had created his own usurper emperor, Eugenius.[50]

Fifth century

[edit]Under Theodosius the Great (emperor 379-395), the new magister militum on the Rhine, Stilicho managed to pacify Lower Germania for a short time. However, the prefecture of Gaul was relocated from Trier, near the Franks, to Vienne in what is now southern France, and then further to Arles, closer to Italy.[51] In about 401/402 Stilicho moved some of his forces to assist with the wars against the Goths, the Rhine was confronted in about 406 with a very large force of Alans and Vandals from eastern Europe. Written reports say it was the Franks who attempted to block them from passing into Gaul, and they succeeded in killing one of the Alan kings, Respendial. In 407, with Gaul and Brittania in chaos and unprotected, another usurper arose there to try to pacify the situation, Constantine III. Stilicho was killed in 408. By about 409 most of these Alans and Vandals had moved to Roman Hispania, but one Alan king remained in Gaul, Goar. The Burgundians, who had been living south of the Franks in the Rhine area for more than a century, took control of some of the main Roman cities within the empire, Worms, Speyer, and Strassburg. The Franks took control of the area around Trier. Constantine III died in 411, and a new usurper Jovinus was proclaimed with Alan and Burgundian support. Within a few decades Trier was taken and plundered by the Franks at least three times.[52] Northern Gaul was no longer effectively being governed by the Roman empire although Roman military commanders were clearly still present there sometimes.[53]

Archaeological evidence indicates sudden immigration of people who introduced rye consumption, and new building and clothing styles. Their jewellery and pottery styles match styles found in what is now northern Germany. There are also signs that Roman gold which started entering the area east of the Rhine around 370 AD, also now started to arrive within the empire itself. Royman and Heeren suggest that usurpers such as Constantine III will have needed to pay off Frankish allies, and that such Franks later started to settle west of the Rhine.[39]

By the 440s a Frankish king named Chlodio pushed beyond Germania Inferior into more Romanized lands south of the "Silva Carbonaria" or "Charcoal forest", which was south of modern Brussels. He conquered Tournai, Artois, Cambrai, and probably reached as far as the Somme river, in the Roman province of Belgica Secunda in what is now northern France. Chlodio is believed to be the ancestor of the future Merovingian dynasty.

From his base in Pannonia and the Middle Danube, Attila and his allies launched a major invasion into Gaul, where they were defeated by a Roman led alliance under the command of Flavius Aetius at the Battle of the Catalaunian Plains in 451 AD. Franks fought on both sides. Jordanes, in his Getica mentions a group called the "Riparii" as auxiliaries of during the Battle of Châlons in 451, and distinct from the "Franci", but these Riparii ("river dwellers") are today not considered to be Ripuarian Franks, but rather a known military unit based on the Rhône.[54]

Childeric I, who according to Gregory of Tours was a reputed descendant of Chlodio, was later seen as administrative ruler over Roman Belgica Secunda and possibly other areas.[55]

Records of Childeric show him to have been active together with Roman forces in the Loire region, quite far to the south. His descendants came to rule Roman Gaul all the way to there, and this became the Frankish kingdom of Neustria, the core of what would become medieval France. Childeric's son Clovis I also took control of the more independent Frankish kingdoms east of the Silva Carbonaria and Belgica II. This later became the Frankish kingdom of Austrasia, where the early legal code was referred to as "Ripuarian".

Merovingian kingdom (481–751)

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2007) |

Gregory of Tours (Book II) reported that small Frankish kingdoms existed during the fifth century around Cologne, Tournai, Cambrai and elsewhere. The kingdom of the Merovingians eventually came to dominate the others, possibly because of its association with Roman power structures in northern Gaul, into which the Frankish military forces were apparently integrated to some extent. In the 450s and 460s, Childeric I, a Salian Frank, was one of several military leaders commanding Roman forces with various ethnic affiliations in Roman Gaul (roughly modern France). Childeric and his son Clovis I faced competition from the Roman Aegidius as competitor for the "kingship" of the Franks associated with the Roman Loire forces (according to Gregory of Tours, Aegidius held the kingship of the Franks for 8 years while Childeric was in exile). This new type of kingship, perhaps inspired by Alaric I,[56] represents the start of the Merovingian dynasty which succeeded in conquering most of Gaul in the 6th century, as well as establishing its leadership over all the Frankish kingdoms on the Rhine frontier. Aegidius died in 464 or 465.[57] Childeric and his son Clovis I were both described as rulers of the Roman Province of Belgica Secunda, by its spiritual leader in the time of Clovis, Saint Remigius.

Clovis later defeated the son of Aegidius, Syagrius, in 486 or 487 and then had the Frankish king Chararic imprisoned and executed. A few years later, he killed Ragnachar, the Frankish king of Cambrai, and his brothers. After conquering the Kingdom of Soissons and expelling the Visigoths from southern Gaul at the Battle of Vouillé, he established Frankish hegemony over most of Gaul, excluding Burgundy, Provence and Brittany, which were eventually absorbed by his successors. By the 490s, he had conquered all the Frankish kingdoms to the west of the River Maas except for the Ripuarian Franks and was in a position to make the city of Paris his capital. He became the first king of all Franks in 509, after he had conquered Cologne.

Clovis I divided his realm between his four sons, who united to defeat Burgundy in 534. Internecine feuding occurred during the reigns of the brothers Sigebert I and Chilperic I, which was largely fuelled by the rivalry of their queens, Brunhilda and Fredegunda, and which continued during the reigns of their sons and their grandsons. Three distinct subkingdoms emerged: Austrasia, Neustria and Burgundy, each of which developed independently and sought to exert influence over the others. The influence of the Arnulfing clan of Austrasia ensured that the political centre of gravity in the kingdom gradually shifted eastwards to the Rhineland.

The Frankish realm was reunited in 613 by Chlothar II, the son of Chilperic, who granted his nobles the Edict of Paris in an effort to reduce corruption and reassert his authority. Following the military successes of his son and successor Dagobert I, royal authority rapidly declined under a series of kings, traditionally known as les rois fainéants. After the Battle of Tertry in 687, each mayor of the palace, who had formerly been the king's chief household official, effectively held power until in 751, with the approval of the Pope and the nobility, Pepin the Short deposed the last Merovingian king Childeric III and had himself crowned. This inaugurated a new dynasty, the Carolingians.

Carolingian kingdom (751–987)

[edit]

The unification achieved by the Merovingians ensured the continuation of what has become known as the Carolingian Renaissance. The Carolingian Empire was beset by internecine warfare, but the combination of Frankish rule and Roman Christianity ensured that it was fundamentally united. Frankish government and culture depended very much upon each ruler and his aims and so each region of the empire developed differently. Although a ruler's aims depended upon the political alliances of his family, the leading families of Francia shared the same basic beliefs and ideas of government, which had both Roman and Germanic roots.[citation needed]

The Frankish state consolidated its hold over the majority of western Europe by the end of the 8th century, developing into the Carolingian Empire. With the coronation of their ruler Charlemagne as Holy Roman Emperor by Pope Leo III in 800 AD, he and his successors were recognised as legitimate successors to the emperors of the Western Roman Empire. As such, the Carolingian Empire gradually came to be seen in the West as a continuation of the ancient Roman Empire. This empire would give rise to several successor states, including France, the Holy Roman Empire and Burgundy, though the Frankish identity remained most closely identified with France.

After the death of Charlemagne, his only adult surviving son became Emperor and King Louis the Pious. Following Louis the Pious's death, however, according to Frankish culture and law that demanded equality among all living male adult heirs, the Frankish Empire was now split between Louis' three sons.

Military

[edit]Participation in the Roman army

[edit]Germanic peoples, including those tribes in the Rhine delta that later became the Franks, are known to have served in the Roman army since the days of Julius Caesar. After the Roman administration collapsed in Gaul in the 260s, the armies under the Germanic Batavian Postumus revolted and proclaimed him emperor and then restored order. From then on, Germanic soldiers in the Roman army, most notably Franks, were promoted from the ranks. A few decades later, the Menapian Carausius created a Batavian–British rump state on Roman soil that was supported by Frankish soldiers and raiders. Frankish soldiers such as Magnentius, Silvanus, Ricomer and Bauto held command positions in the Roman army during the mid 4th century. From the narrative of Ammianus Marcellinus it is evident that both Frankish and Alamannic tribal armies were organised along Roman lines.

After the invasion of Chlodio, the Roman armies at the Rhine border became a Frankish "franchise" and Franks were known to levy Roman-like troops that were supported by a Roman-like armour and weapons industry. This lasted at least until the days of the scholar Procopius (c. 500 – c. 565), more than a century after the demise of the Western Roman Empire, who wrote describing the former Arborychoi, having merged with the Franks, retaining their legionary organization in the style of their forefathers during Roman times.[58] The Franks under the Merovingians melded Germanic custom with Romanised organisation and several important tactical innovations. Before their conquest of Gaul, the Franks fought primarily as a tribe, unless they were part of a Roman military unit fighting in conjunction with other imperial units.

Military practices of the early Franks

[edit]

The primary sources for Frankish military custom and armament are Ammianus Marcellinus, Agathias and Procopius, the latter two Eastern Roman historians writing about Frankish intervention in the Gothic War.

Writing of 539, Procopius says:

At this time the Franks, hearing that both the Goths and Romans had suffered severely by the war ... forgetting for the moment their oaths and treaties ... (for this nation in matters of trust is the most treacherous in the world), they straightway gathered to the number of one hundred thousand under the leadership of Theudebert I and marched into Italy: they had a small body of cavalry about their leader, and these were the only ones armed with spears, while all the rest were foot soldiers having neither bows nor spears, but each man carried a sword and shield and one axe. Now the iron head of this weapon was thick and exceedingly sharp on both sides, while the wooden handle was very short. And they are accustomed always to throw these axes at a signal in the first charge and thus to shatter the shields of the enemy and kill the men.[59]

His contemporary, Agathias, who based his own writings upon the tropes laid down by Procopius, says:

The military equipment of this people [the Franks] is very simple ... They do not know the use of the coat of mail or greaves and the majority leave the head uncovered, only a few wear the helmet. They have their chests bare and backs naked to the loins, they cover their thighs with either leather or linen. They do not serve on horseback except in very rare cases. Fighting on foot is both habitual and a national custom and they are proficient in this. At the hip they wear a sword and on the left side their shield is attached. They have neither bows nor slings, no missile weapons except the double edged axe and the angon which they use most often. The angons are spears which are neither very short nor very long. They can be used, if necessary, for throwing like a javelin, and also in hand to hand combat.[60]

In the Strategikon, supposedly written by the emperor Maurice, or in his time, the Franks are lumped together with the Lombards under the heading of the "fair-haired" peoples.

If they are hard pressed in cavalry actions, they dismount at a single prearranged sign and line up on foot. Although only a few against many horsemen, they do not shrink from the fight. They are armed with shields, lances, and short swords slung from their shoulders. They prefer fighting on foot and rapid charges. [...] Either on horseback or on foot they are impetuous and un- disciplined in charging, as if they were the only people in the world who are not cowards.[61]

While the above quotations have been used as a statement of the military practices of the Frankish nation in the 6th century and have even been extrapolated to the entire period preceding Charles Martel's reforms (early mid-8th century), post-Second World War historiography has emphasised the inherited Roman characteristics of the Frankish military from the date of the beginning of the conquest of Gaul. The Byzantine authors present several contradictions and difficulties. Procopius denies the Franks the use of the spear while Agathias makes it one of their primary weapons. They agree that the Franks were primarily infantrymen, threw axes and carried a sword and shield. Both writers also contradict the authority of Gallic authors of the same general time period (Sidonius Apollinaris and Gregory of Tours) and the archaeological evidence. The Lex Ribuaria, the early 7th century legal code of the Rhineland or Ripuarian Franks, specifies the values of various goods when paying a wergild in kind; whereas a spear and shield were worth only two solidi, a sword and scabbard were valued at seven, a helmet at six, and a "metal tunic" at twelve.[62] Scramasaxes and arrowheads are numerous in Frankish graves even though the Byzantine historians do not assign them to the Franks.

The evidence of Gregory and of the Lex Salica implies that the early Franks were a cavalry people. In fact, some modern historians have hypothesised that the Franks possessed so numerous a body of horses that they could use them to plough fields and thus were agriculturally technologically advanced over their neighbours. The Lex Ribuaria specifies that a mare's value was the same as that of an ox or of a shield and spear, two solidi and a stallion seven or the same as a sword and scabbard,[62] which suggests that horses were relatively common. Perhaps the Byzantine writers considered the Frankish horse to be insignificant relative to the Greek cavalry, which is probably accurate.[63]

Merovingian military

[edit]Composition and development

[edit]The Frankish military establishment incorporated many of the pre-existing Roman institutions in Gaul, especially during and after the conquests of Clovis I in the late 5th and early 6th centuries. Frankish military strategy revolved around the holding and taking of fortified centres (castra) and in general these centres were held by garrisons of milities and laeti, who were descendants of Roman soldiers with Germanic origin, granted a quasi-national status under Frankish law. These milites continued to be commanded by tribunes.[64] Throughout Gaul, the descendants of Roman soldiers continued to wear their uniforms and perform their ceremonial duties.

Immediately beneath the Frankish king in the military hierarchy were the leudes, his sworn followers, who were generally 'old soldiers' in service away from court.[65] The king had an elite bodyguard called the truste. Members of the truste often served in centannae, garrison settlements that were established for military and police purposes. The day-to-day bodyguard of the king was made up of antrustiones (senior soldiers who were aristocrats in military service) and pueri (junior soldiers and not aristocrats).[66] All high-ranking men had pueri.

The Frankish military was not composed solely of Franks and Gallo-Romans, but also contained Saxons, Alans, Taifals and Alemanni. After the conquest of Burgundy (534), the well-organised military institutions of that kingdom were integrated into the Frankish realm. Chief among these was the standing army under the command of the Patrician of Burgundy.

In the late 6th century, during the wars instigated by Fredegund and Brunhilda, the Merovingian monarchs introduced a new element into their militaries: the local levy. A levy consisted of all the able-bodied men of a district who were required to report for military service when called upon, similar to conscription. The local levy applied only to a city and its environs. Initially only in certain cities in western Gaul, in Neustria and Aquitaine, did the kings possess the right or power to call up the levy. The commanders of the local levies were always different from the commanders of the urban garrisons. Often the former were commanded by the counts of the districts. A much rarer occurrence was the general levy, which applied to the entire kingdom and included peasants (pauperes and inferiores). General levies could also be made within the still-pagan trans-Rhenish stem duchies on the orders of a monarch. The Saxons, Alemanni and Thuringii all had the institution of the levy and the Frankish monarchs could depend upon their levies until the mid-7th century, when the stem dukes began to sever their ties to the monarchy. Radulf of Thuringia called up the levy for a war against Sigebert III in 640.

Soon the local levy spread to Austrasia and the less Romanised regions of Gaul. On an intermediate level, the kings began calling up territorial levies from the regions of Austrasia (which did not have major cities of Roman origin). All the forms of the levy gradually disappeared, however, in the course of the 7th century after the reign of Dagobert I. Under the so-called rois fainéants, the levies disappeared by mid-century in Austrasia and later in Burgundy and Neustria. Only in Aquitaine, which was fast becoming independent of the central Frankish monarchy, did complex military institutions persist into the 8th century. In the final half of the 7th century and first half of the 8th in Merovingian Gaul, the chief military actors became the lay and ecclesiastical magnates with their bands of armed followers called retainers. The other aspects of the Merovingian military, mostly Roman in origin or innovations of powerful kings, disappeared from the scene by the 8th century.

Strategy, tactics and equipment

[edit]Merovingian armies used coats of mail, helmets, shields, lances, swords, bows and arrows and war horses. The armament of private armies resembled those of the Gallo-Roman potentiatores of the late Empire. A strong element of Alanic cavalry settled in Armorica influenced the fighting style of the Bretons down into the 12th century. Local urban levies could be reasonably well-armed and even mounted, but the more general levies were composed of pauperes and inferiores, who were mostly farmers by trade and carried ineffective weapons, such as farming implements. The peoples east of the Rhine – Franks, Saxons and even Wends – who were sometimes called upon to serve, wore rudimentary armour and carried weapons such as spears and axes. Few of these men were mounted.[citation needed]

Merovingian society had a militarised nature. The Franks called annual meetings every Marchfeld (1 March), when the king and his nobles assembled in large open fields and determined their targets for the next campaigning season. The meetings were a show of strength on behalf of the monarch and a way for him to retain loyalty among his troops.[67] In their civil wars, the Merovingian kings concentrated on the holding of fortified places and the use of siege engines. In wars waged against external foes, the objective was typically the acquisition of booty or the enforcement of tribute. Only in the lands beyond the Rhine did the Merovingians seek to extend political control over their neighbours.

Tactically, the Merovingians borrowed heavily from the Romans, especially regarding siege warfare. Their battle tactics were highly flexible and were designed to meet the specific circumstances of a battle. The tactic of subterfuge was employed endlessly. Cavalry formed a large segment of an army [citation needed], but troops readily dismounted to fight on foot. The Merovingians were capable of raising naval forces: the naval campaign waged against the Danes by Theuderic I in 515 involved ocean-worthy ships and rivercraft were used on the Loire, Rhône and Rhine.

Culture

[edit]Language

[edit]In a modern linguistic context, the language of the early Franks is variously called "Old Frankish" or "Old Franconian" and these terms refer to the language of the Franks prior to the advent of the High German consonant shift, which took place between 600 and 700 AD. After this consonant shift the Frankish dialect diverges, with the dialects which would become modern Dutch not undergoing the consonantal shift, while all others did so to varying degrees.[68] As a result, the distinction between Old Dutch and Old Frankish is largely negligible, with Old Dutch (also called Old Low Franconian) being the term used to differentiate between the affected and non-affected variants following the aforementioned Second Germanic consonant shift.[69]

The Frankish language has not been directly attested, apart from a very small number of runic inscriptions found within contemporary Frankish territory such as the Bergakker inscription. Nevertheless, a significant amount of Frankish vocabulary has been reconstructed by examining early Germanic loanwords found in Old French as well as through comparative reconstruction through Dutch.[70][71] The influence of Old Frankish on contemporary Gallo-Roman vocabulary and phonology, have long been questions of scholarly debate.[72] Frankish influence is thought to include the designations of the four cardinal directions: nord "north", sud "south", est "east" and ouest "west" and at least an additional 1000 stem words.[71]

Although the Franks would eventually conquer all of Gaul, speakers of Frankish apparently expanded in sufficient numbers only into northern Gaul to have a linguistic effect. For several centuries, northern Gaul was a bilingual territory (Vulgar Latin and Frankish). The language used in writing, in government and by the Church was Latin. Urban T. Holmes has proposed that a Germanic language continued to be spoken as a second tongue by public officials in western Austrasia and Northern Neustria as late as the 850s, and that it completely disappeared as a spoken language during the 10th century from regions where only French is spoken today.[73]

The Germanic tribes who were called Franks in Late Antiquity are associated with the Weser–Rhine Germanic/Istvaeonic cultural-linguistic grouping.[74][75][76]

Art and architecture

[edit]

Early Frankish art and architecture belongs to a phase known as Migration Period art, which has left very few remains. The later period is called Carolingian art, or, especially in architecture, pre-Romanesque. Very little Merovingian architecture has been preserved. The earliest churches seem to have been timber-built, with larger examples being of a basilica type. The most completely surviving example, a baptistery in Poitiers, is a building with three apses of a Gallo-Roman style. A number of small baptistries can be seen in Southern France: as these fell out of fashion, they were not updated and have subsequently survived as they were.

Jewelry (such as brooches), weapons (including swords with decorative hilts) and clothing (such as capes and sandals) have been found in a number of grave sites. The grave of Queen Aregund, discovered in 1959, and the Treasure of Gourdon, which was deposited soon after 524, are notable examples. The few Merovingian illuminated manuscripts that have survived, such as the Gelasian Sacramentary, contain a great deal of zoomorphic representations. Such Frankish objects show a greater use of the style and motifs of Late Antiquity and a lesser degree of skill and sophistication in design and manufacture than comparable works from the British Isles. So little has survived, however, that the best quality of work from this period may not be represented.[77]

The objects produced by the main centres of the Carolingian Renaissance, which represent a transformation from that of the earlier period, have survived in far greater quantity. The arts were lavishly funded and encouraged by Charlemagne, using imported artists where necessary, and Carolingian developments were decisive for the future course of Western art. Carolingian illuminated manuscripts and ivory plaques, which have survived in reasonable numbers, approached those of Constantinople in quality. The main surviving monument of Carolingian architecture is the Palatine Chapel in Aachen, which is an impressive and confident adaptation of San Vitale, Ravenna – from where some of the pillars were brought. Many other important buildings existed, such as the monasteries of Centula or St Gall, or the old Cologne Cathedral, since rebuilt. These large structures and complexes made frequent use of towers.[78]

Religion

[edit]A sizeable portion of the Frankish aristocracy quickly followed Clovis in converting to Christianity (the Frankish church of the Merovingians). The conversion of all under Frankish rule required a considerable amount of time and effort.

Paganism

[edit]

Echoes of Frankish paganism can be found in the primary sources, but their meaning is not always clear. Interpretations by modern scholars differ greatly, but it is likely that Frankish paganism shared most of the characteristics of other varieties of Germanic paganism. The mythology of the Franks was probably a form of Germanic polytheism. It was highly ritualistic. Many daily activities centred around the multiple deities, chiefest of which may have been the Quinotaur, a water-god from whom the Merovingians were reputed to have derived their ancestry.[79] Most of their gods were linked with local cult centres and their sacred character and power were associated with specific regions, outside of which they were neither worshipped nor feared. Most of the gods were "worldly", possessing form and having connections with specific objects, in contrast to the God of Christianity.[80]

Frankish paganism has been observed in the burial site of Childeric I, where the king's body was found covered in a cloth decorated with numerous bees. There is a likely connection with the bees to the traditional Frankish weapon, the angon (meaning "sting"), from its distinctive spearhead. It is possible that the fleur-de-lis is derived from the angon.

Christianity

[edit]Some Franks, like the 4th century usurper Silvanus, converted early to Christianity. In 496, Clovis I, who had married a Burgundian Catholic named Clotilda in 493, was baptised by Saint Remi after a decisive victory over the Alemanni at the Battle of Tolbiac. According to Gregory of Tours, over three thousand of his soldiers were baptised with him.[81] Clovis' conversion had a profound effect on the course of European history, for at the time the Franks were the only major Christianised Germanic tribe without a predominantly Arian aristocracy and this led to a naturally amicable relationship between the Catholic Church and the increasingly powerful Franks.

Although many of the Frankish aristocracy quickly followed Clovis in converting to Christianity, the conversion of all his subjects was only achieved after considerable effort and, in some regions, a period of over two centuries.[82] The Chronicle of St. Denis relates that, following Clovis' conversion, a number of pagans who were unhappy with this turn of events rallied around Ragnachar, who had played an important role in Clovis' initial rise to power. Although the text remains unclear as to the precise pretext, Clovis had Ragnachar executed.[83] Remaining pockets of resistance were overcome region by region, primarily due to the work of an expanding network of monasteries.[84]

The Merovingian Church was shaped by both internal and external forces. It had to come to terms with an established Gallo-Roman hierarchy that resisted changes to its culture, Christianise pagan sensibilities and suppress their expression, provide a new theological basis for Merovingian forms of kingship deeply rooted in pagan Germanic tradition and accommodate Irish and Anglo-Saxon missionary activities and papal requirements.[85] The Carolingian reformation of monasticism and church-state relations was the culmination of the Frankish Church.

The increasingly wealthy Merovingian elite endowed many monasteries, including that of the Irish missionary Columbanus. The 5th, 6th and 7th centuries saw two major waves of hermitism in the Frankish world, which led to legislation requiring that all monks and hermits follow the Rule of St Benedict.[86] The Church sometimes had an uneasy relationship with the Merovingian kings, whose claim to rule depended on a mystique of royal descent and who tended to revert to the polygamy of their pagan ancestors. Rome encouraged the Franks to slowly replace the Gallican Rite with the Roman rite.

Laws

[edit]As with other Germanic peoples, the laws of the Franks were memorised by "rachimburgs", who were analogous to the lawspeakers of Scandinavia.[87]

By the 6th century, when these laws first appeared in written form, two basic legal subdivisions existed: Salian Franks were subject to Salic law and Ripuarian Franks to Ripuarian law. The Salic legal code applied in the Neustrian area from the river Liger (Loire) to the Silva Carbonaria, a forest south of present-day Brussels. It represented the boundary of the original area of Frankish settlement, which Chlodio pushed past in the 5th century..

The Ripuarian law was apparently used on the other side of the Silva Carbonaria, in the older Frankish kingdoms. The Rhineland or "Ripuarian" Franks who lived near the stretch of the Rhine from roughly Mainz to Duisburg, the region of the city of Cologne, are often considered separately from the Salians, and sometimes in modern texts referred to as Ripuarian Franks. The Ravenna Cosmography suggests that Francia Renensis included the old civitas of the Ubii, in Germania II (Germania Inferior), but also the northern part of Germania I (Germania Superior), including Mainz. Like the Salians they appear in Roman records both as raiders and as contributors to military units. Unlike the Salii, there is no record of when, if ever, the empire officially accepted their residence within its borders. They eventually succeeded to hold the city of Cologne, and at some point seem to have acquired the name Ripuarians, which may have meant "river people". In any case a Merovingian legal code was called the Lex Ribuaria, but it probably applied in all the older Frankish lands, including the original Salian areas.

Gallo-Romans south of the River Loire and the clergy remained subject to traditional Roman law.[88] Germanic law was overwhelmingly concerned with the protection of individuals and less concerned with protecting the interests of the state. According to Michel Rouche, "Frankish judges devoted as much care to a case involving the theft of a dog as Roman judges did to cases involving the fiscal responsibility of curiales, or municipal councilors".[89]

Crusaders and other Western Europeans as "Franks"

[edit]

The term Frank has been used by many of the Eastern Orthodox and Muslim neighbours of medieval Latin Christendom (and beyond, such as in Asia) as a general synonym for a European from Western and Central Europe, areas that followed the Latin rites of Christianity under the authority of the pope in Rome.[90] Another term with similar use was Latins.

Christians following the Latin rites in the eastern Mediterranean in this period were called Franks or Latins, regardless of their country of origin, whereas the words Rhomaios and Rûmi ("Roman") were used for Orthodox Christians. On a number of Greek islands, Catholics are still referred to as Φράγκοι (Frangoi) or "Franks", for instance on Syros, where they are called Φραγκοσυριανοί (Frangosyrianoi). The period of Crusader rule in Greek lands is known to this day as the Frankokratia ("rule of the Franks").

The Mediterranean Lingua Franca (or "Frankish language") was a pidgin first spoken by 11th century European Christians and Muslims in Mediterranean ports that remained in use until the 19th century.

The term Frangistan ("Land of the Franks") was used by Muslims to refer to Christian Europe and was commonly used over several centuries in Iberia, North Africa, and the Middle East. Persianate Turkic dynasties used and spread the term in throughout Iran and India with the expansion of the language. During the Mongol Empire in the 13th–14th centuries, the Mongols used the term "Franks" to designate Europeans,[91] and this usage continued into Mughal times in India in the form of the word firangi.[92]

The Chinese called the Portuguese Folangji 佛郎機 ("Franks") in the 1520s at the Battle of Tunmen and Battle of Xicaowan. Some other varieties of Mandarin Chinese pronounced the characters as Fah-lan-ki.

During the reign of Chingtih (Zhengde) (1506), foreigners from the west called Fah-lan-ki (or Franks), who said they had tribute, abruptly entered the Bogue, and by their tremendously loud guns shook the place far and near. This was reported at court, and an order returned to drive them away immediately, and stop the trade.

— Samuel Wells Williams, The Middle Kingdom: A Survey of the Geography, Government, Education, Social Life, Arts, Religion, &c. of the Chinese Empire and Its Inhabitants, 2 vol. (Wiley & Putnam, 1848).

Examples of derived words include:

- Frangos (Φράγκος) in Greek

- Frëng in Albanian

- Frenk in Turkish

- Firəng in Azerbaijani[93] (derived from Persian)

- al-Faranj, Afranj and Firinjīyah in Arabic[94]

- Farang (فرنگ), Farangī (فرنگی) in Persian, also the toponym Frangistan (فرنگستان)

- Faranji in Tajik.[95]

- Ferengi or Faranji in some Turkic languages

- Ferenj (ፈረንጅ) in Amharic in Ethiopia, Farangi (ፋራንጂ) in Tigrinya, and similar in other languages of the Horn of Africa, refers to white people with European ancestry

- Feringhi or Firang in Hindi and Urdu (derived from Persian)

- Phirangee in some other Indian languages

- Parangiar in Tamil

- Parangi in Malayalam; in Sinhala, the word refers specifically to Portuguese people

- Bayingyi (ဘရင်ဂျီ) in Burmese[96]

- Barang in Khmer

- Feringgi in Malay

- Folangji[97] or Fah-lan-ki (佛郎機) and Fulang[98] in Chinese

- Farang (ฝรั่ง) in Thai.

- Pirang ("blonde"), Perangai ("temperament/al") in Bahasa Indonesia

In the Thai usage, the word can refer to any European person. When the presence of US soldiers during the Vietnam War placed Thai people in contact with African Americans, they (and people of African ancestry in general) came to be called Farang dam ("Black Farang", ฝรั่งดำ). Such words sometimes also connote things, plants or creatures introduced by Europeans/Franks. For example, in Khmer, môn barang, literally "French Chicken", refers to a turkey and in Thai, Farang is the name both for Europeans and for the guava fruit, introduced by Portuguese traders over 400 years ago. In contemporary Israel, the Yiddish[citation needed] word פרענק (Frenk) has, by a curious etymological development, come to refer to Mizrahi Jews in Modern Hebrew and carries a strong pejorative connotation.[99]

Some linguists (among them Drs. Jan Tent and Paul Geraghty) have suggested that the Samoan and generic Polynesian term for Europeans, Palagi (pronounced Puh-LANG-ee) or Papalagi, might also be cognate, possibly a loan term gathered by early contact between Pacific islanders and Malays.[100]

See also

[edit]- Germanic Christianity

- List of Frankish kings

- List of Frankish queens

- Name of France

- List of Germanic peoples

- Frankokratia

References

[edit]- ^ Wickham, Chris (2010) [2009]. The Inheritance of Rome: Illuminating the Dark Ages 400–1000. Penguin History of Europe, 2. Penguin Books. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-670-02098-0.

- ^ a b Murray, Alexander Callander (2000). From Roman to Merovingian Gaul: A Reader. Broadview Press. p. 1.

The etymology of 'Franci' is uncertain ('the fierce ones' is the favourite explanation), but the name is undoubtedly of Germanic origin.

- ^ Perry 1857, p. 42.

- ^ a b Nonn 2010, p. 14.

- ^ a b Beck 1995.

- ^ XII Panegyrici Latini 6(7).11.4 to Constantine. Translation and notes: Nixon & Rodgers 1994, p. 107.

- ^ Nonn 2010, p. 11.

- ^ Murray 1999, pp. 590–596.

- ^ Murray 1999, p. 590.

- ^ Wallace-Hadrill 1962, p. 82.

- ^ Dörler 2013, pp. 25–32.

- ^ Ewig 1998, p. 21.

- ^ Ewig 1998, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Geary 1988, pp. 77–78.

- ^ Anton 1995, p. 414.

- ^ Neumann 1981a, p. 369.

- ^ Petrokovits 1981b, p. 392 citing Ammianus Marcellinus 20.20.

- ^ a b c Petrokovits 1981a, p. 369.

- ^ Wallace-Hadrill 1962, p. 148.

- ^ Nonn 2010, pp. 29–31.

- ^ Baldwin 1978, p. 56.

- ^ Runde 1998, p. 657.

- ^ Runde 1978, p. 658 and Verlinden 1974, p. 4 citing Zosimos, Historia nova I.30.2-3 (written around 500 AD); Aurelius Victor, De Caesaribus 33.1-3; Eutropius the historian, Breviarium IX.8.2 (in the 4th century); and Orosius, Historiae VII 22.7 and 41.2 (written around 400 AD).

- ^ a b Anton 1995, pp. 414–415.

- ^ Liccardo 2023, p. 89.

- ^ Anton 1995, pp. 414–415, Runde 1978, pp. 659–660 citing Zosimos, Historia nova I.68.1.

- ^ Nixon & Rodgers 1994, p. 139.

- ^ Runde 1978, p. 660.

- ^ Historia Augusta, The Lives of Firmus, Saturninus, Proculus and Bonosus [1]

- ^ Runde 1978, p. 661 and Nixon & Rodgers 1994, p. 107 citing Eutropius, Breviarium IX 8,2, and Orosius, Historiae, VII.25.3.

- ^ XII Panegyrici Latini, 10(2).10.3-5 and 11(3).5.4. Latin version ed. Emil Baehrens, XII Panegyrici Latini p.97; and translation in Nixon & Rodgers 1994, pp. 68 and 89.

- ^ XII Panegyrici Latini 11(3).7.2. For a translation and further comments see Nixon & Rodgers 1994, p. 92

- ^ Williams, 50–51.

- ^ Barnes, Constantine and Eusebius, 7.

- ^ Lanting & van der Plicht 2010, p. 67 citing XII Panegyrici Latini 8(4).9.3. For a translation and further comments see Nixon & Rodgers 1994, p. 121

- ^ XII Panegyrici Latini, 6(7) of 310 AD, 10.2, 11.5, 12.1, Translation and further comments: Nixon & Rodgers 1994, pp. 232–236

- ^ Nixon & Rodgers 1994, p. 362.

- ^ Liccardo 2023, pp. 55–56.

- ^ a b Roymans & Heeren 2021.

- ^ a b c Runde 1998, p. 665, note 46, Heather 2020

- ^ Reimitz 2004.

- ^ Res Gestae, XVII.8.

- ^ Springer 1997, p. 64.

- ^ Springer 1997, p. 67.

- ^ Springer 1997, pp. 81–83.

- ^ Runde 1998, p. 669.

- ^ Nixon & Rodgers 1994, p. 518.

- ^ Roymans 2021.

- ^ Runde 1988, p. 671.

- ^ Runde 1988, pp. 672–673.

- ^ Runde 1988, p. 673.

- ^ Runde 1988, p. 674.

- ^ Halsall 2007, p. 218.

- ^ Nonn "Die Franken", p. 85: "Heute dürfte feststehen, dass es sich dabei um römische Einheiten handelt; die in der Gallia riparensis, einem Militärbezirk im Rhônegebiet, stationiert waren, der in der Notitia dignitatum bezeugt ist."

- ^ Gregory of Tours was apparently skeptical of Childeric's connection to Chlodio, and only says that some say there was such a connection. Concerning Belgica Secunda, which Chlodio had conquered first for the Franks, Bishop Remigius, the leader of the church in the same province, stated in a letter to Childeric's son Clovis that "Great news has reached us that you have taken up the administration of Belgica Secunda. It is no surprise that you have begun to be as your parents ever were." (Epistolae Austriacae, translated by AC Murray, and quoted in Murray's "From Roman to Merovingian Gaul" p. 260). This is normally interpreted to mean that Childeric also had this administration. (See for example Wood "The Merovingian Kingdoms" p. 41.) Both the passage of Gregory and the letter of Remigius note the nobility of Clovis's mother when discussing his connection to this area.

- ^ Halsall (2007, p. 267)

- ^ James (1988, p. 70)

- ^ Helmut Reimitz (2015). History, Frankish Identity and the Framing of Western Ethnicity, 550–850. Cambridge University Press. pp. 79–80. ISBN 978-1-107-03233-0.

- ^ Procopius HW, VI, xxv, 1ff, quoted in Bachrach (1970), 436.

- ^ Agathias, Hist., II, 5, quoted in Bachrach (1970), 436–437.

- ^ Maurice's Strategikon. Handbook Of Byzantine Military Strategy. Translated by Dennis, George T. p. 119.

- ^ a b James, Edward, The Franks. Oxford; Blackwell 1988, p. 211

- ^ Bachrach (1970), 440.

- ^ Bernard S. Bachrach (1972). Merovingian Military Organization, 481–751. University of Minnesota Press. pp. 79–80. ISBN 978-0-8166-5700-1.

- ^ Halsall, Guy. Warfare and Society in the Barbarian West, 450–900 (London: Routledge, 2003), p. 48

- ^ Halsall, pp. 48–49

- ^ Halsall, p. 43

- ^ Rheinischer Fächer – Karte des Landschaftsverband Rheinland "LVR Alltagskultur im Rheinland". Archived from the original on February 15, 2009. Retrieved October 23, 2017.

- ^ B. Mees, "The Bergakker inscription and the beginnings of Dutch", in: Amsterdamer beiträge zur älteren Germanistik: Band 56-2002, edited by Erika Langbroek, Annelies Roeleveld, Paula Vermeyden, Arend Quak, Published by Rodopi, 2002, ISBN 978-90-420-1579-1

- ^ van der Horst, Joop (2000). Korte geschiedenis van de Nederlandse taal (Kort en goed) (in Dutch). Den Haag: Sdu. p. 42. ISBN 90-5797-071-6.

- ^ a b "Romance languages | Description, Origin, Characteristics, Map, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. 21 July 2023.

- ^ Noske 2007, p. 1.

- ^ U. T. Holmes, A. H. Schutz (1938), A History of the French Language, p. 29, Biblo & Tannen Publishers, ISBN 0-8196-0191-8

- ^ R.L. Stockman: Low German, University of Michigan, 1998, p. 46.

- ^ K. Reynolds Brown: Guide to Provincial Roman and Barbarian Metalwork and Jewelry in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1981, p. 10.

- ^ H. Schutz: Tools, Weapons and Ornaments: Germanic Material Culture in Pre-Carolingian Central Europe, 400–750. Brill, 2001, p. 42.

- ^ Otto Pächt, Book Illumination in the Middle Ages (trans fr German), 1986, Harvey Miller Publishers, London, ISBN 0-19-921060-8

- ^ Eduard Syndicus; Early Christian Art; pp. 164–174; Burns & Oates, London, 1962

- ^ Schutz, 152.

- ^ Gregory of Tours, in his History of the Franks, relates: "Now this people seems to have always been addicted to heathen worship, and they did not know God, but made themselves images of the woods and the waters, of birds and beasts and of the other elements as well. They were wont to worship these as God and to offer sacrifice to them." (Gregory of Tours, History of the Franks, Book I.10 Archived 2014-08-14 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ Gregory of Tours. "Book II, 31". History of the Franks. Archived from the original on 2014-08-14. Retrieved 2007-07-20.

- ^ Sönke Lorenz (2001), Missionierung, Krisen und Reformen: Die Christianisierung von der Spätantike bis in Karolingische Zeit in Die Alemannen, Stuttgart: Theiss; ISBN 3-8062-1535-9; pp. 441–446

- ^ The Chronicle of St. Denis, I.18–19, 23 Archived 2009-11-25 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Lorenz (2001:442)

- ^ J.M. Wallace-Hadrill covers these areas in The Frankish Church (Oxford History of the Christian Church; Oxford:Clarendon Press) 1983.

- ^ Michel Rouche, 435–436.

- ^ Michel Rouch, 421.

- ^ Michel Rouche, 421–422.

- ^ Michel Rouche, 422–423

- ^ König, Daniel G., Arabic-Islamic Views of the Latin West. Tracing the Emergence of Medieval Western Europe, Oxford: OUP, 2015, chap. 6, p. 289-230.[page needed]

- ^ Igor de Rachewiltz – Turks in China under the Mongols, in: China Among Equals: The Middle Kingdom and its Neighbors, 10th–14th Centuries, p. 281

- ^ Nandini Das – Courting India, p. 107

- ^ "FİRƏNG". Azərbaycan dilinin izahlı lüğəti [Explanatory dictionary of the Azerbaijani language] (in Azerbaijani). Archived from the original on 15 August 2020. Retrieved 15 August 2020 – via Obastan.

Danışıq dilində "fransız" mənasında işlədilir.

- ^ Rashid al-din Fazl Allâh, quoted in Karl Jahn (ed.) Histoire Universelle de Rasid al-Din Fadl Allah Abul=Khair: I. Histoire des Francs (Texte Persan avec traduction et annotations), Leiden, E. J. Brill, 1951. (Source: M. Ashtiany)

- ^ Kamoludin Abdullaev; Shahram Akbarzaheh (2010). Historical Dictionary of Tajikistan. Scarecrow Press. pp. 129–. ISBN 978-0-8108-6061-2.

- ^ Myanmar-English Dictionary. Myanmar Language Commission. 1996. ISBN 1-881265-47-1.

- ^ Endymion Porter Wilkinson (2000). Chinese History: A Manual. Harvard Univ Asia Center. pp. 730–. ISBN 978-0-674-00249-4.

- ^ Park, Hyunhee (2012). Mapping the Chinese and Islamic Worlds: Cross-Cultural Exchange in Pre-Modern Asia. Cambridge University Press. pp. 95–. ISBN 978-1-107-01868-6.

- ^ Batya Shimony (2011) On "Holocaust Envy" in Mizrahi Literature, Dapim: Studies on the Holocaust, 25:1, 239–271, doi:10.1080/23256249.2011.10744411. p. 241: "Frenk [a pejorative slang term for Mizrahi]"

- ^ Tent, J., and Geraghty, P., (2001) "Exploding sky or exploded myth? The origin of Papalagi", Journal of the Polynesian Society, 110, 2: pp. 171–214.

Sources

[edit]Secondary sources

[edit]- Anton, Hand H. (1995), "Franken § 17. Erstes Auftauchen im Blickfeld des röm. Reiches und erste Ansiedlung frk. Gruppen", in Beck, Heinrich; Geuenich, Dieter; Steuer, Heiko (eds.), Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde, vol. 9 (2 ed.), De Gruyter, pp. 414–419, ISBN 978-3-11-014642-4

- Bachrach, Bernard S. Merovingian Military Organization, 481–751. University of Minnesota Press, 1971. ISBN 0-8166-0621-8

- Baldwin, B (1978), "Verses in the "Historia Augusta"", Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies, 25 (25): 50–58, doi:10.1111/j.2041-5370.1978.tb00384.x, JSTOR 43645974

- Beck, Heinrich (1995), "Franken § 1. Namenkundliches", in Beck, Heinrich; Geuenich, Dieter; Steuer, Heiko (eds.), Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde, vol. 9 (2 ed.), De Gruyter, pp. 373–374, ISBN 978-3-11-014642-4

- Collins, Roger. Early Medieval Europe 300–1000. MacMillan, 1991.

- Dörler, Philipp (2013). "The Liber Historiae Francorum – a Model for a New Frankish Self-confidence". Networks and Neighbours. 1: 23–43. S2CID 161310931.

- Ewig, Eugen (1998). "Trojamythos und fränkische Frühgeschichte". In Geuenich, Dieter (ed.). Die Franken und die Alemannen bis zur "Schlacht bei Zülpich" (496/97). Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde - Ergänzungsbände. Vol. 19. De Gruyter. pp. 2–30. ISBN 978-3-11-015826-7.

- Geary, Patrick J. (1988). Before France and Germany: The Creation and Transformation of the Merovingian World. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-504458-4.

- Geipel, John (1970) [1969]. The Europeans: The People – Today and Yesterday: Their Origins and Interrelations. Pegasus: a division of Western Publishing Company, Inc.

- Greenwood, Thomas (1836). The First Book of the History of the Germans: Barbaric period. Longman, Rees, Orne, and Co.

- Halsall, Guy (2007). Barbarian Migrations and the Roman West 376–568.

- Heather, Peter J. (2020), "The Gallic Wars of Julian Caesar", A Companion to Julian the Apostate, Brill, doi:10.1163/9789004416314_004

- Howorth, Henry H. (1884). "XVII. The Ethnology of Germany (Part VI). The Varini, Varangians and Franks. Section II". Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. 13. Trübner & Co.: 213–239. doi:10.2307/2841727. JSTOR 2841727.

- James, Edward (1988). The Franks. The Peoples of Europe. Oxford, UK; Cambridge, Massachusetts: Basil Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-17936-4.

- Lewis, Archibald R. "The Dukes in the Regnum Francorum, A.D. 550–751." Speculum, Vol. 51, No 3 (July 1976), pp. 381–410.

- Lanting; van der Plicht (2010). "De 14C-chronologie van de Nederlandse Pre- en Protohistorie VI: Romeinse tijd en Merovingische periode, deel A: historische bronnen en chronologische schema's". Palaeohistoria. 51/52: 67. ISBN 978-90-77922-73-6.

- Liccardo, Salvatore (2023), Old Names, New Peoples: Listing Ethnonyms in Late Antiquity, Brill, doi:10.1163/9789004686601, ISBN 978-90-04-68660-1

- McKitterick, Rosamond. The Frankish Kingdoms under the Carolingians, 751–987. London: Longman, 1983. ISBN 0-582-49005-7.

- Murray, Alexander Callander; Goffart, Walter (1998), After Rome's Fall: Narrators and Sources of Early Medieval History, University of Toronto Press

- Murray, Alexander Callander (1999), From Roman to Merovingian Gaul: A Reader, Readings in Medieval Civilizations and Cultures, University of Toronto Press, ISBN 9781442689732

- Nixon, C E V; Rodgers, Barbara Saylor (1994). In praise of later Roman emperors: the Panegyrici Latini. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-08326-1 – via Internet Archive.

- Nonn, Ulrich (2010). Die Franken.

- Noske, Roland (2007). "Autonomous typological prosodic evolution versus the Germanic superstrate in diachronic French phonology". In Aboh, Enoch; van der Linden, Elisabeth; Quer, Josep; et al. (eds.). Romance Languages and Linguistic Theory (PDF). Amsterdam; Philadelphia: Benjamins. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2011-12-30.

- Perry, Walter Copland (1857). The Franks, from Their First Appearance in History to the Death of King Pepin. Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans, and Roberts.

- Petrikovits, Harald (1981a), "Chamaven § 2. Historisches", in Beck, Heinrich; Geuenich, Dieter; Steuer, Heiko (eds.), Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde, vol. 4 (2 ed.), De Gruyter, pp. 368–370, ISBN 978-3-11-006513-8

- Petrikovits, Harald (1981b), "Chattwarier § 2. Historisches", in Beck, Heinrich; Geuenich, Dieter; Steuer, Heiko (eds.), Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde, vol. 4 (2 ed.), De Gruyter, pp. 392–393, ISBN 978-3-11-006513-8

- Pfister, M. Christian (1911). "(B) The Franks Before Clovis". In Bury, J.B. (ed.). The Cambridge Medieval History. Vol. I: The Christian Roman Empire and the Foundation of the Teutonic Kingdoms. Cambridge University Press.

- Reimitz, Helmut (2004), "Salier § 2. Historisches", in Beck, Heinrich; Geuenich, Dieter; Steuer, Heiko (eds.), Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde, vol. 26 (2 ed.), De Gruyter, pp. 344–347, ISBN 978-3-11-017734-3

- Roymans, Nico; Heeren, Stijn (2021), "Romano-Frankish interaction in the Lower Rhine frontier zone from the late 3rd to the 5th century – Some key archaeological trends explored", Germania, 99: 133–156, doi:10.11588/ger.2021.92212

- Runde, Ingo (1998). "Die Franken und Alemannen vor 500. Ein chronologischer Überblick". In Geuenich, Dieter (ed.). Die Franken und die Alemannen bis zur "Schlacht bei Zülpich" (496/97). Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde - Ergänzungsbände. Vol. 19. De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-015826-7.

- Schutz, Herbert. The Germanic Realms in Pre-Carolingian Central Europe, 400–750. American University Studies, Series IX: History, Vol. 196. New York: Peter Lang, 2000.

- Seebold, Elmar (2000), "Wann und wo sind die Franken vom Himmel gefallen?", Beiträge zur Geschichte der deutschen Sprache und Literatur, 122 (1): 40–56, doi:10.1515/bgsl.2000.122.1.40