Francisco Javier Carrillo Gamboa

Francisco Javier Carrillo | |

|---|---|

| Born | Querétaro, Qro., México |

| Education | National Autonomous University of Mexico (BA, Msc) London School of Economics (MSc) King's College London (PhD) |

| Years active | 1971 – present |

Francisco Javier Carrillo[a] is an international researcher and practitioner in knowledge management, capital systems, knowledge cities and knowledge for the Anthropocene. He is the creator of the triadic KM Model, the capital systems and a taxonomy of knowledge markets as well as the founder of the World Capital Institute.

Background

[edit]Early life and locations

[edit]Francisco Javier Carrillo Gamboa was born in the City of Querétaro, State of Querétaro, México on November 15, 1953. His father was José Carrillo García and his mother María Elena Gamboa Ocampo.[1] In 1965 he went to boarding high school (secondary, preparatory and Ecole Normale) in Puebla.[2][3] He moved to Mexico City in 1971, where he worked as a teacher at several institutions throughout his B.Sc. studies (1974–1978).[4][5][6][3][2][1] In 1981 he married Rosa María Sánchez Cantú, with whom he shares life to this day. They lived in London from 1981 through late 1986 where they both coursed graduate studies and obtained their respective Ph.D. degrees at the University of London. They successively moved to Guadalajara (1987), Monterrey (1989) and Querétaro (2019).

Graduate and undergraduate education

[edit]He graduated from Ecole Normale at Instituto Juan Ponce de León in Puebla in 1973.[5][3] He studied his B.Sc. degree from 1972 through 1976 at Instituto Universitario de Ciencias de la Educación in Mexico City, a private university incorporated to Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM) with a major on Experimental Psychology, graduating with honours from UNAM[4] with a dissertation on Behaviour Modification for Parents.[7] While working for his BSc degree, he received the influence of Francisco Cabrer, Joanne Moller, Herminia Casanova, and Luis Castro from the Faculty of Psychology at UNAM. He published his first co-authored paper with the later in 1976.[8]

In 1979, he started an M.Sc. in Experimental Analysis of Behavior at UNAM, where he received the influence of Florente López, Emilio Ribes, Joao Claudio Todorov, John E. R. Staddon, Franciska Feekes, Víctor Colotla, Hank Davis, Jerry Hogan, Paul Henry and Juan J. Sánchez-Sosa. His dissertation, on variable interval reinforcement programs was directed by Arturo Bouzas, graduating in 1981.[9]

In September 1981 he entered the M.Sc in Logic and Scientific Method at the London School of Economics. His views on Scientific Behaviour were at odds with the dominant Popperian views of most faculty at the LSE. However, the contrasting views of Imre lakatos, Thomas Kuhn, Paul Feyerabend and others vested at several fori,[10][11] opened alternative avenues later enriched by several individual and organizations through the UK and Europe at large.

In 1983 he moved to the Centre for Science and Mathematics Education at Chelsea College, later to become the Centre for Educational Studies at King’s College, London, for his doctoral research on the Psychology of Science. He worked under the joint supervision of Paul Black Head of the Assessment of Performance Unit of the UK Department of Education and Science[12] and Joan Bliss, a disciple of Jean Piaget. He obtained his Ph.D. in 1986 with an empirical and theoretical analysis of basic Patterns of Scientific Behaviour.[13]

Professional career

[edit]He taught Language and Hispanic Literature at various secondary schools in Mexico City since 1971, and lectured Psychology courses at various Ecole Normale also in Mexico City, including Psychology of Learning and Developmental Psychology. He became also an instructor of Operant Conditioning Lab courses at IUCE. Upon graduation he taught Experimental Psychology, Methodology, Learning and Educational Technology at IUCE, Universidad Anáhuac and Tecnológico de Monterrey, Estado de México campus. He continued working part-time as a Psychology lecturer in various universities in Mexico City until leaving for England in 1981.

Soon after graduating, he took a position as a Psychologist at the Departamento del Distrito Federal from 1976 through 1977. In 1977 he engaged in the Behaviour Modification unit at the psychological consultancy and clinical services firm M.I.R.A., S.A.

Willing to comply with the commitment to serve at a Public centre upon returning to Mexico after completing his Ph.D. partially with a CONACyT studentship, he accepted an invitation from Universidad de Guadalajara’s Departamento de Investigación Científica y Superación Académica (DICSA) to develop a research performance assessment unit for the same time as the duration of his studentship, i.e., two and a half years. During his stay he also organized the First National Conference on Scientific Research and Technological Innovation and was a member of the commission for the design of the Centro Nacional de Evaluacion de la Educación Superior of the Federal Government Ministry of Public Education.

By mid-1989 he and his wife, Dr. Rosa María Sánchez, accepted a full-time position at Tecnológico de Monterrey main campus in Monterrey, where they served until retirement in 2018. Both served in several capacities during this period. In his case, predominantly as Director if the Synapsis distant education program and, over 25 years, as creator and Director of the Centre for Knowledge Systems. In 2015 was incorporated into a new R&D structure along the creation of national schools at Tecnológico de Monterrey. He became Head of the national Strategic Focus Research Group on Knowledge Societies until his retirement in 2018.[14][15]

While at CSC, he received tenure in 1990 and taught mostly graduate courses in research methods, knowledge and intellectual capital management, capital systems, and development theory at the schools of Engineering, Management, Social Sciences, Humanities and Education. Over this period, he directed over 20 M.Sc. dissertations and 12 doctoral ones. He was also a guest external member of about 20 graduate dissertation committees in universities in the Americas, Europe, and Australia.[15][14] Further engagements while at Tecnológico de Monterrey include Director of the Pascal Centre for Latin America[16] and Head of the CEMEX-ITESM Research Chair.[17][18][19][20][21]

The Center for Knowledge Systems

[edit]In 1990, the Center for Knowledge Systems (CKS) was created operating continuously through 2015, when research and graduate activities -and with these most research centres- were reorganized around National Schools. Arguably the first dedicated KM R&D unit in the world,[22] the CKS soon became a very active research, graduate studies and consultancy centre, with a strong interaction between academic activities and consultancy contracts.[23][24] Throughout its 25 years of existence, it was financially self-sufficient.[25]

Since its inception, the CKS pursued a deliberate networking initiative, which resulted in the development of special relationships with KM and IC pioneer institutions such as the Knowledge Management Consortium International, George Washington University, the Knowledge Sciences Center at Kent State University and the Global Development Learning Network (GDLN), in the US; the Basque Country Knowledge Cluster, the Knowledge Society Research Center at the Autonomous University of Madrid the National University of Distant Education, The Deusto University, the Mondragón University and The Extremadura University in Spain; the Sorbonne University, the LABCIS at Poitiers and the Arenotech network in France; the National University, Del Rosario University at Bogotá, Universidad of Valle at Cali, University of the North at Barranquilla, the PFANGCTI, the Government of Caldas and the Municipalities of Medellín and Manizales in Colombia; the University of Caxias do Sul, Federal University of Santa Catarina and Institute of Applied Economic Research in Brazil, the ECLAC in Chile, ILO/CINTERFOR in Uruguay and ADIAT, CONACYT, The Secretariat of Public Education, and CIDE in Mexico. From this wide relational context, he founded the Ibero-American Community for Knowledge Systems (CISC) in 2000.[26][27]

The World Capital Institute (WCI)

[edit]He created in 2004 the World Capital Institute (WCI) as a think-tank consolidating the global community of knowledge-based development. Its main programs are the annual conference (Knowledge Cities World Summit-KCWS[28]) awards (Most Admired Knowledge City -MAKCi[29][30][31]), research and publications. It focused on[32][33] promoting knowledge as the main leverage to development. Its core topics were Knowledge Based Development and Knowledge Cities.[34][35][36][37]

“As the emphasis shifted from KM to KBD among some members of the KM and IC communities, the WCI arose from an initial concept: the accountability of major entities (governments, corporations, and international agencies) by the net value (assets minus liabilities) they provide to the world in terms of total tangible and intangible capital. Even though that line of research proved difficult to implement, it is now considered particularly relevant in light of the Anthropocene, and it is being reactivated. Nevertheless, the WCI achieved substantial progress in other KBD areas, particularly in assessing and developing knowledge city-regions. Recently, it has extended KBD to the areas of alternative economic cultures, knowledge for the Anthropocene and city preparedness for the climate crisis”.[38]

Retirement

[edit]By the end of 2018 Javier and Rosa María moved to Querétaro City, where they continue engaged in several professional and civic programs. He carries on his work at WCI, became an Emeritus Professor at Tecnológico de Monterrey engaged in R&D and Graduate activities, and continues to be an active member of the National Researchers System (Level III).

Civic action

[edit]Once in Querétaro he engaged in several environmental action groups, notably the Asociación del Parque Intraurbano Jurica fighting to preserve the Natural Protected Area at Western Jurica[39] and the Hydro-ecology Jurica Committee aiming at protecting regional hydric resources and preventing watersheds.

Distinctions

[edit]He graduated with honours from his B.Sc. He was the recipient of a CONACyT studentship for his M.Sc. at UNAM and both his M.Sc. and part of his Ph.D. at London University. He then received the Overseas Research Student Award (ORS).

After completing his Ph.D., he became a member of Sigma-Xi (1996),[40] the Mexican National Researchers System-SNI (2004),[41] and the Mexican Academy of Sciences (2009).[42][4] He is co-founder and Editor-In-Chief of the International Journal of Knowledge Based Development.[43]

Work

[edit]Empirical Epistemology and the Science of Science

[edit]While working for his MSc at UNAM, he became aware of the reflexivity between the Methodology of Research in Experimental Psychology and the Behavioural dimensions of Scientific Practice. From this realization his first book -Scientific Behaviour-[44] emerged. This approach moulded his initial research interests[45][46] and paved the way for his PhD research and were nourished by his association with the Science of Science movement[47] and his affiliation to Science Studies professional associations while in the UK, such as the 4S and the EAAST.

Empirical Epistemology and the Psychology of Science were hallmarks of his early work: “Several scientific disciplines have ventured into specific aspects of knowledge phenomena, complementing philosophy of science with a sciences of science perspective. In the 1960’s, the science of science movement, based on the progressive social perspectives of J. D. Bernal undertook a critical reflection of science as a matter of social concern.[48] Leading figures such as Derek de Solla Price, C. P. Snow, and Maurice Goldsmith advocated for “the examination of the phenomenon of ‘science’ by the methods of science itself”.[49] The science of science movement set the ground for the social responsibility of science movement, as well as the consolidation of the sciences of knowledge. Similarly, the post-normal science approach led by Jerome Ravetz[50][51] contextualized knowledge in a VUCA world. Naturalized epistemology,[52][53][54] or empirical epistemology[55][56][57] complements the former review of epistemological schools with the factual inputs and theoretical insights from scientific disciplines that have delved into aspects formerly restricted to philosophical analysis. Rather than encroaching upon the later, empirical epistemology has contributed to the understanding of knowledge by furthering philosophical inquiry with new realizations and perspectives. This approach is fundamental to an integrated theory of knowledge, complementing attempts at comprehensive accounts from the fronts of socio-politics of knowledge,[58] social epistemology,[59] or history of cognition[60]”.

KM model and processes

[edit]

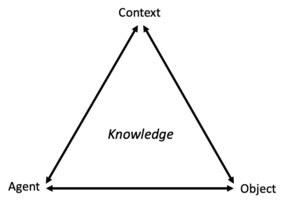

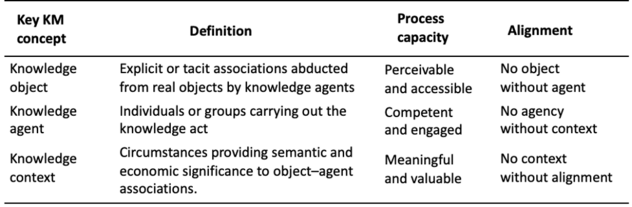

“Knowledge can be approached from two perspectives: either as content to act upon or as a value-creating event. In the latter sense, a key task is to determine the conditions for knowing to happen. A knowledge event comes about when object–agent–context attributes correspond with each other. Under these conditions, knowledge constitutes an emergent integration. It occurs when these three factors are effectively and mutually aligned.

As a result, KM aims at a deliberate alignment of knowledge objects, agents, and contexts. Just as the occurrence of fire (chemical chain reaction) requires the functional convergence of flammable material, heat, and oxygen (reactants) in adequate parameters, knowledge requires all three elements to occur in adequate parameters. It is not enough to aggregate objects, agents, and contexts, although this is a precondition that increases the likelihood of knowledge to happen, much as storing combustible materials in non-insulated spaces increases the risk of accidental fire. Deliberately starting a fire requires proportionate flammable material, oxygen, and heat. Fire management takes place by properly adjusting flammability, oxygenation, and temperature. Fire prevention and suppression is carried out by excluding or removing any of these. Similarly, alignment between knowledge objects, agents and contexts is enabled through KM by identifying the relevant dimensions of each and making sure these correspond”.[62]

“Hence, strategic alignment becomes a core Knowledge Management (KM) process. The primacy of alignment has been pointed out in the management literature as much as the complexity of the concept and the challenges of measuring it. The knowledge object–agent–context alignment constitutes the essence of KM. According to the explanation above, this is achieved by identifying, measuring, and designing the correspondence between the attributes of objects, agents and contexts. The removal of the process capacity of any element will result in meaning and value dilution, for it will no longer be knowledge and will become useless. Unless a competent knowledge agent is provided with adequate contextual clues to interpret the knowledge object and act accordingly, value realization will be impaired”.[63] Based on these concepts Carrillo and his colleagues at CKS developed a comprehensive knowledge management processes guidelines and strategy.[64]

Capital systems

[edit]

“A capital system is a universe of collective preference orders within a system of human activity – those elements that stakeholders acknowledge as being valuable at all levels of analysis: individual, organizational, social, and global. A category can be disaggregated into successive subcategories, each of which highlights a distinctive and complementary value function. Each holds a negative (liability) or positive (asset) sign relative to the direction in which it operates on the whole system. It is necessary to give operational definitions to each of the first-order categories before moving on to subsequent-order categories. A capital system has the potential to overcome the dichotomy between tangible and intangible capital as well as simultaneously defining a value domain and a general capital construct. This, in turn, makes possible a general value account system and a composite indicator.

The attributes of a capital system are:

- The set constitutes a homogeneous value whole. A capital system denotes a culture.

- The set cannot be reduced to any of its constituent parts (financial capital cannot express the whole).

- Every capital expresses a value dimension of its own and is exchangeable with others according to correspondence rules”.[66]

Taxonomy of capital[67]

| Capital System

Universe of value orders of collective preference |

Metacapital

Multiplicative (Divisive) |

Referential

Structure: rules of belonging |

Identity

Auto-significance |

Capacity to differentiate value elements belonging into the system and to consequently adjusting action |

| Intelligence

Alo-significance |

Capacity to identify significant agents and events in the system and responding accordingly | |||

| Articulating

Function: rules of relationship |

Monetary

Exchange |

Capacity to represent and exchange value elements | ||

| Relational

Bonding |

Capacity to establish and develop bonds with significant others | |||

| Productive

Additive (Subtractive) |

Input | Natural services, cultural heritage, and exogenous value | ||

| Agent

Action |

Capacity to perform value-increasing actions | |||

| Instrumental

Mediation |

Capacity to leverage the performance of value-increasing actions | |||

| Output | Cumulative addition to or subtraction from a system | |||

“The rationale for a capital system can be summarized as follows:

- A production function is inherent in all value systems. It refers to the system’s ability to achieve and sustain value balance.

- In all production functions, an input, an agent, an instrument and a product are involved. These are productive capitals. Productive capitals belong to all forms of value systems.

- Throughout history, meta-capitals were developed as a means to multiply the value-generating capability of productive capitals. With the creation of currencies, productive capitals could be represented and exchanged, increasing their spatial and temporal potential. Hence, financial capital was created.

- There are two major forms of meta-capital involved in knowledge-based production. Referential meta-capital multiplies the effectiveness and efficiency of the system by providing focus, thus diminishing error (through increasingly precise internal and external feedback). This includes identity and intelligence capitals. Articulating meta-capital multiplies the productivity of the system by providing cohesion, thus diminishing transaction costs and redundancies. It includes financial and relational capital.

When we are successful in accurately and consistently capturing the capital system of any given entity, we are representing its value blueprint, the state of the system with reference to its ideal state (such as homeostasis in living systems). Such an ideal state would be one where each of the value elements existed just in the right proportion to achieving full balance. Hence, value systems are unique, as unique as personalities or cultures; and, therefore, capital systems are as diverse as the multiplicity of systems amenable to a singular description. This would apply to every individual, every organization, and every society. Through emphasizing meta-productive values, we begin to comprehend that no single form of value has primacy: it is only the degree of equilibrium of all value elements (whatever their relative weights) that becomes an ideal for all existing systems”.[68]

Knowledge Based Development (KBD)

[edit]In “What Knowledge Based Development Stands for”[33] Carrillo summarized the critical analysis of this movement in the following terms:

- The dominant view of KBD stems from the intention to leverage aggregate production though k-intensive factors (science and technology, education, and innovation).

- A corollary of that view is that a KBD policy aims at improving global competitiveness of a given collective (city, region, and nation) through the attraction, retention, multiplication, and capitalization of k-intensive resources.

- Productivity, though, may be expanded to account for all results of human activity contributing to overall future social worth.

- The reach of the KBD concept has been constrained by received views on what ‘k-based’ denotes. Amongst received views, two are prominent:

- Instrumental view: economic growth can be promoted through adequate access to k-intensive resources (science and technology, human capital, digital connectivity, and green economy).

- Incremental view: attainment of ‘lower’ stages of social progress will eventually lead to ‘higher’ stages: an information and technology-intensive environment will breed a knowledge society.

- Since concepts and theories to address the issues involved in the two former views pre-existed KBD, unless this latter concept proves distinct and meaningful, it could be rendered obsolete and subsume within mainstream areas such as technological progress, regional innovation, urban development, sustainability and so forth.

- The current attempt to assign a distinct meaning to KBD is identified as disruptive, radical, or holistic, insofar, it requires dealing with all relevant value dimensions for a given community. Also, once knowledge is entered as the main element in social value dynamics, new functional realities emerge that radically transform the space of possibilities.

- The notion of KBD undertaken here aims at a dynamic identification, measurement and balance among major value elements shared by a community.

- The knowledge-based attribute refers to an economic, political, and cultural order, placing as much emphasis on the intangible value or intellectual assets as it has so far done on the material and monetary ones.

- Two developments contribute to substantiate the viability of the disruptive view of KBD:

- Capital systems as a universal language to capture all relevant value dimensions in a community within a nested taxonomy.

- Knowledge markets as a new breed of value exchanges where the quantity, quality and terms of interactions amongst agents are all determined primordially by the dynamic properties of IC.

Drawing on these proposals and advancements, KBD can be defined as: the collective identification and enhancement of the value set whose dynamic balance furthers the viability and transcendence of a given community.”

This perspective enables a sensible pursue of human social improvement without resource to the biophysical unviability of indefinite economic growth or the lost currency of the development neocolonial ideology.[33]

Knowledge Markets

[edit]‘Occupy the market!’ becomes more than a resistance expression under a KBD perspective. It becomes the possibility -well documented in numerous and diverse settings- to redefine social value exchange beyond the restrictive dogmas of economic liberalism. Knowledge markets are value transaction system where the quantity, quality, and terms of interactions amongst agents are determined primordially by the dynamic properties of intellectual capital. This concept involves the following demarcation criteria:

- predominance of knowledge capital in value-exchange content.

- appeal to open, self-organization.

- reduction of intermediation and transaction costs.

- mixed use of traditional and low-tech techniques such as one-to-one barter, local currencies, social swarming, talent banks, with state-of-the-art leveraging technologies such as matching algorithms, ubiquitous computing, smart contracts, flash organizations, decentralized autonomous organizations, and so on.

- emphasis on a distinctive set of values, such as transparency, trust, equality, and balance; and

- awareness and capitalization of the properties of knowledge-based value creation and distribution. On these bases, he developed a Taxonomy of Knowledge Markets with some slight variations throughout the years:[69]

Knowledge for the Anthropocene

[edit]As Carrillo personally and the WCI at large shifted focus by adding to the original KBD and Knowledge Cities topics an emphasis on Alternative Economic Thinking and Doing as well as on Knowledge for the Anthropocene and on City Preparedness for the Climate Crisis. He recruited a WCI team to convey an international state-of-the-art report on each of these issues, with respective reports published in 2021.[70][71]

In the Foreword to the former, Noel Castree captures the challenge: “But the ‘wickedness’ of the Anthropocene problem, the variety of possible means and ends required to ‘fix’ it, and the inertia caused by those favouring the status quo will make action very slow, very fragmented, and highly contested. Where does ‘knowledge’ feature in this incipient socio-ecological transformation? What kinds of knowledge are required to steer a path forward? Whose knowledge should exert influence in the world to come? What areas of ignorance do we need to shine a light on with new or repurposed knowledge? How can different bodies of knowledge be brought into a productive dialogue? And can knowledge be deployed effectively and quickly? This book seeks to answer these large and very important questions.”[72]

Regarding City Preparedness, Carrillo summarized the circumstance in the Introduction to the later: “In order to responsibly face the environmental conditions of the Anthropocene as these unfold, we must closely examine the axiological and conceptual foundations of our cities and question their environmental economic, cultural, and political underpinnings. This requires a deep questioning not just of modern urban living, but of the whole way of inhabiting Earth. No urban mitigation, adaptation or reform will suffice unless such deeper scrutiny takes place. No fashionable urban development framework, be it the smart, sustainable, or resilient city, is up to the task unless the whole Holocene City paradigm is scrutinized. This means letting go of the very way of life that brought us here. This means farewell to the Holocene City.”[73]

An integrated theory of knowledge

[edit]In 2022, he published A Modern Guide to Knowledge: From Knowledge Economies to Knowledge in the Anthropocene. Therein, he condeses most of his work on knowledge as a basis to address the unprecedented challenges of the Anthropocene: “Outlining an integrative theory of knowledge, Francisco Javier Carrillo explores how to understand the underlying behavioural basis of the knowledge economy and society. Chapters highlight the notion that unless a knowledge-based value creation and distribution paradigm is globally adopted, the possibilities for integration between a sustainable biosphere and a viable economy are small.”[72]

Bibliography

[edit]Authored books

[edit]- Carrillo, F. J. (2022). A Modern Guide to Knowledge: From Knowledge Societies to Knowledge in the Anthropocene. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Carrillo, F. J., Lönnqvist, A., García, B. and Yigitcanlar, T. (2014). Knowledge and the City: Concepts, Applications and Trends of Knowledge-Based Urban Development. New York, U.S.: Routledge.

- Carrillo, F. J. (1983). El Comportamiento Científico. Mexico City: Limusa-Wiley.

Edited books

[edit]- Carrillo, F. J., and Koch G. (2021). Knowledge for the Anthropocene. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Carrillo, F. J., and Garner C. (2021). City Preparedness for the Climate Crisis. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Carrillo, F. J. (2014). Sistemas de Capitales y Mercados de Conocimiento. Seattle, U.S.: Amazon Kindle Direct Publishing.

- Yigitcanlar, T. Metaxiotis, K. and Carrillo, F. J. (2012). Building Prosperous Knowledge Cities: Policies, Plans and Metrics. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Carrillo, F. J. (2011). Knowledge Cities: Approaches, Experiences and Perspectives (Arabic Edition). Kuwait City: National Council for Culture, Arts and Letters.

- Metaxiotis, K., Yigitcanlar, T. and Carrillo, F. J. (2010). Knowledge-Based Development for Cities and Societies: Integrated Multi-Level Approaches. Information Science Reference / IGI Global.

- Batra, S. and Carrillo, F. J. (2009). Knowledge Management and Intellectual Capital: Emerging Perspectives. New Delhi: Allied Publishers.

- Carrillo, F. J. (2008). Desarrollo Basado en el Conocimiento. Monterrey, N.L.: Fondo Editorial Nuevo León.

- Carrillo, F. J. (2005). Knowledge Cities: Approaches, Experiences and Perspectives. Burlington, MA, USA: Elsevier / Butterworth-Heinemann.

- Carrillo (2005). Prácticas de Valor de Gestión Tecnológica en México. México: CONACyT / ADIAT.

Notes

[edit]- ^ In this Spanish name, the first or paternal surname is Carrillo and the second or maternal family name is Gamboa.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Lexis-Nexis, Group (2000). Marquis Who's Who In The World 2000 - Millenium Edition. p. 335.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ a b Pellam, J. L. (2005). The Barons 500. Leaders for the New Century. Barons Who’s Who (2000 Commemorative Edition). p. 133.

- ^ a b c Zavala, J. R (2009). Científicos y Tecnólogos de Nuevo León, México. Diccionario Biográfico (Segunda Edición). Colegio de Estudios Científicos y Tecnológicos del Estado de Nuevo León (CECyTE, NL). Volumen 1 (A – K). pp. 108–110.

- ^ a b c Academia Mexicana de Ciencias (2009). Ingreso de Nuevos Miembros. Semblanzas. Academia Mexicana de Ciencias. pp. 22–23.

- ^ a b Zavala, J. R. (2005). Científicos y Tecnólogos de Nuevo León, México Diccionario Biográfico (2nd ed.). Colegio de Estudios Científicos y Tecnológicos del Estado de Nuevo León (CECyTE, NL). pp. 60–61.

- ^ Pellam, J. L. (1996). Who's Who in Global Banking and Finance. 200-2001 International Edition. Barons Who’s Who. p. 56.

- ^ Carrillo, F. J. and Becerril, C. F., (1978). Implementación de un Programa de Entrenamiento en Modificación de Conducta para Padres de Familia. Tesis de Licenciatura. IUCE/UNAM.

- ^ Castro, L. y Carrillo, F. J. (1976). Ritmos Circadianos y Control Comportamental”, Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología 8 (3), 459-466.

- ^ Carrillo, F. J. (1981). Duración de los Componentes y Contraste Local en Programas Múltiples. Tesis de Maestría en Análisis Experimental de la Conducta. Facultad de Psicología, UNAM.

- ^ Radnitzky, G., & Andersson, G. (Eds.) (1978). Progress and rationality in science. Reidel.

- ^ Lakatos, Musgrave, I., A. (1970). Criticism and the growth of knowledge: Proceedings of the International Colloquium in the Philosophy of Science, London,1965 (Vol. 4 ed.). Cambridge University Press.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Johnson, S. (1989). National assessment: The APU science approach. Her Majesty’s Stationery Office

- ^ Carrillo, F.J. (1986). Acquisition of Scientific Patterns of Behaviour: The Science Teacher Interface. Doctoral Dissertation. King’s College (KQC), University of London

- ^ a b "F. J. Carrillo profile at LinkedIn [EN]".

- ^ a b "F. J. Carrillo research profile at Tecnológico de Monterrey [EN]".

- ^ "Tecnológico de Monterrey Becomes next Pascal Centre".

- ^ Bodero, I. (2010, Septiembre 9). Industria-Academia: binomio para el enriquecimiento. Panorama, Nº. 1649, Año XLIII, p. 8.

- ^ Garza, A. (2012, Febrero). Veinte años del Centro de Sistemas de Conocimiento se consolidan mediante la Cátedra de Investigación: Administración de Conocimiento-CEMEX. Boletín ACTING Nº 2, pp. 6-7

- ^ Buendia, A. (2014, Abril 7). Vinculan Empresa y Escuela. El Norte, Sección Negocios, p. 15.

- ^ "Revista Transferencia (2011). Número Especial: Las Redes de Investigación. Cátedra de Investigación -Administración de Conocimiento CEMEX. Transferencia 94 (24). Tecnológico de Monterrey".

- ^ Ramírez, M. (2010, Abri 19). Acuerdan aplicar conocimiento al desarrollo tecnológico. Panorama, Nº 1644, Año XLIII

- ^ Skyrme, D. J., & Amidon, D. M. (1997). Creating the knowledge-based business. Key lessons from an international study of best practice. Business Intelligence Limited

- ^ Ortiz, A. (2012, Septiembre 26). Celebran 20 años de impulsar la Gestión del Conocimiento. Panorama, Nº. 1713, Año XLVI

- ^ Garcia, L. M. (2012, Marzo 15). Dos décadas de darle al conocimiento su valor. Panorama, Nº 1707, Año XLVI, p. 5

- ^ Carrillo, F. J. (2022). A modern Guide to Knowledge: From Knowledge Societies to Knowledge in The Anthropocene. Edward Elgar. p. 49, note 34.

- ^ "Universidad de Chile (2011, 1º de Junio). Red PILA CHILE alista su segundo seminario-curso sobre Propiedad Industrial en Valparaíso. Universia Chile: Noticias".

- ^ "Carvajal, F. (2009, Abril). Gestión del Conocimiento: Un Asunto de Conciencia. AUPEC: Agencia Universitaria de Periodismo Científico. Universidad del Valle, Cali".

- ^ Michelam, L. D., Cortese, T. T. P., Yigitcanlar, T., Fachinelli, A. C., Vils, L., & Levy, W. (2021). Leveraging smart and sustainable development via international events: Insights from Bento Gonçalves Knowledge Cities World Summit. Sustainability, 13(17), Article 9937

- ^ Garcia, B. (2021). Knowledge city benchmarking and the MAKCi experience. In F. J. Carrillo (Ed.) City preparedness for the climate crisis. Edward Elgar Publishing. pp. 129–140.

- ^ Garcia ., B. (2008). "Global KBD community developments: The MAKCi experience". Journal of Knowledge Management. 12 (5): 91–106. doi:10.1108/13673270810902966.

- ^ Chase, R., & Carrillo, F. J. (2007). The 2007 Most Admired Knowledge City report. World Capital Institute and Teleos

- ^ Von Mutius, B. (2005). Rethinking leadership in the knowledge society learning from others: How to integrate intellectual and social capital and establish a new balance of value and values. In A. Bounfour & L. Edvinsoon (Eds.), Intellectual capital for communities (pp. 151–163). Butterworth-Heinemann

- ^ a b c Carrillo, F. J. (2014). "What "knowledge-based" stands for? A position paper". International Journal of Knowledge-Based Development. 5 (4): 402–421. doi:10.1504/IJKBD.2014.068067.

- ^ Carrillo, F. J., Yigitcanlar, T., García, B., & Lönnqvist, A. (2014). Knowledge and the city: Concepts, applications and trends of knowledge-based urban development. Routledge

- ^ Van Wezemael, J. (2012). Concluding: Directions for building prosperous knowledge cities. In T. Yigicanlar, K. Metaxiotis & F. J. Carrillo (Eds.), Building prosperous knowledge cities: Policies, plans and metrics. Edward Elgar Publishing. pp. 374–382.

- ^ Yigitcanlar, T., & Inkinen, T. (2019). Theory and practice of knowledge cities and knowledge-based urban development. In Geographies of disruption (pp. 109–133). Springer

- ^ Carrillo, F. J. (Ed.) (2006a). Knowledge cities: Approaches, experiences, and perspectives. Butterworth-Heinemann

- ^ Carillo, F. J. (2022). A modern Guide to Knowledge: From Knowledge Societies to Knowledge in The Anthropocene. Edward Elgar. pp. xvi.

- ^ "Secretaría de Desarrollo Sustentable del Estado de Querétaro (2018). Áreas Naturales Protegidas: Decreto Jurica Poniente".

- ^ "Sigma Xi, The Scientific Research Honor Society. Member Directory".

- ^ "Sistema Nacional de Investigadores. Archivo Histórico del SNI. Investigadores Vigentes".

- ^ Ramírez, M. (2009, Noviembre 13). Ingresan a la Academia Mexicana de Ciencias. Panorama, Nº. 1573, Año 42, p. x.

- ^ "Inderscience Publishers (2018, January). New Editor for International Journal of Knowledge-Based Development". 8 January 2019.

- ^ Carrillo, F. J. (1983). El Comportamiento Científico. Limusa-Wiley.

- ^ Carrillo, F. J. (1983c). Empirical epistemology: A behavioural programme for science

- ^ Carrillo, F. J. (1983). Psychology of science: A matter of choice [Paper presentation]. Joint EASST/STSA Conference: Choice in Science and Technology, London

- ^ [Paper presentation]. First European Meeting of Experimental Analysis of Behavior, Liège, Belgium.

- ^ Goldsmith, M. (1965). The science of science. Nature. pp. 205(4966), 10–14.

- ^ Bernal, J. D. (1967). The social function of science, 1939. Routledge

- ^ Ravetz, J. R. (1990). The merger of knowledge with power: Essays in critical science. Mansell Publishing

- ^ Ravetz, J. R. (1979). Scientific knowledge and its social problems. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Kornblith, H. (2002). Knowledge and its place in nature. Oxford University Press

- ^ Quine, W. V. (1995). Naturalism; or, living within one's means. Dialectica. pp. 49(2–4), 251–263.

- ^ Quine, W. V. (1969). Epistemology naturalized. In Ontological relativity and other essays (pp. 69–90). Columbia University Press

- ^ Charles, E. P. (2013). Psychology: The empirical study of epistemology and phenomenology. Review of General Psychology, 17(2), 140–144

- ^ Kosso, P. (1991). Empirical epistemology and philosophy of science (22(4) ed.). Metaphilosophy. pp. 349–363.

- ^ Carrillo, F. J. (1983c). Empirical epistemology: A behavioural programme for science [Paper presentation]. First European Meeting of Experimental Analysis of Behavior, Liège, Belgium

- ^ Stehr, N. "The social and political control of knowledge in modern societies". International Social Science Journal: 55(178), 643–655.

- ^ Fuller, S. (2007). The knowledge book. Routledge.

- ^ Renn, J. (2020). The evolution of knowledge: Rethinking science for the Anthropocene. Princeton University Press

- ^ Carrillo, F. J. (1988). "Managing knowledge‐based value systems". Journal of Knowledge Management. 1 (4): 28–46.

- ^ Carrillo, F. J. (2022). A modern Guide to Knowledge: From Knowledge Societies to Knowledge in The Anthropocene. Edward Elgar. pp. 112–113.

- ^ Carrillo, F. J. (2022). A modern Guide to Knowledge: From Knowledge Societies to Knowledge in The Anthropocene. Edward Elgar. p. 117.

- ^ Carrillo and Galvis-Lista, F. J. and E. (2014). Procesos de gestión de conocimiento desde el enfoque de sistemas de valor basados en conocimiento. Ideas CONCYTEG 9(107). pp. 3–22.

- ^ Carrillo, F. J. (2002). "Capital systems: Implications for a global knowledge agenda". Journal of Knowledge Management. 6 (4): 379–399. doi:10.1108/13673270210440884.

- ^ Carrillo, F. J. (2022). A modern Guide to Knowledge: From Knowledge Societies to Knowledge in The Anthropocene. Edward Elgar. p. 117.

- ^ Carrillo, F. J. (2002). "Capital systems: Implications for a global knowledge agenda". Journal of Knowledge Management. 6 (4): 379–399. doi:10.1108/13673270210440884.

- ^ Carrillo, F.J.; González, O.; Elizondo, G.; Correa, A. (2014). Marco Analítico de Sistemas de capitales. En Sistemas de capitales y mercados de conocimiento. Amazon Kindle Direct Publishing. pp. Cap. 1.

- ^ Carrillo, F. J. (2016). International Knowledge markets: A typology and an overview. Journal of Knowledge-based Development. pp. 7(3), 264–289.

- ^ Carrillo & Garner, F. J., C. (2021). City Preparedness for the Climate Crisis: A Multidisciplinary Approach. Edward Elgar Publishing.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Carrillo & Koch, F. J., G. (2021). Knowledge for the Anthropocene: A Multidisciplinary Approach. Edward Elgar Publishing.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Carrillo, F. J. (2022). A Modern Guide to Knowledge. From Knowledge Economies to Knowledge in the Anthropocene. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- ^ Carrillo, F. J. (2021). Introduction. In City Preparedness for the Climate Crisis: A Multidisciplinary Approach. Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 2.