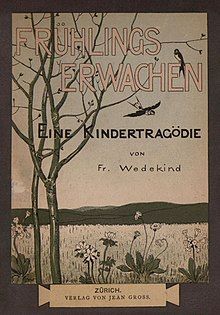

Spring Awakening (play)

| Spring Awakening A Children's Tragedy | |

|---|---|

First edition 1891 | |

| Written by | Frank Wedekind |

| Date premiered | 20 November 1906 |

| Place premiered | Deutsches Theater, Berlin |

| Original language | German |

| Subject | Coming of age, sexual awakening |

| Setting | Provincial German town, 1890–1894 |

Spring Awakening (German: Frühlings Erwachen) (also translated as Spring's Awakening and The Awakening of Spring) is the German dramatist Frank Wedekind's first major play and a foundational work in the modern history of theatre.[1][2] It was written sometime between autumn 1890 and spring 1891, but did not receive its first performance until 20 November 1906 when it premiered at the Deutsches Theater in Berlin under the direction of Max Reinhardt. It carries the sub-title A Children's Tragedy.[3] The play criticises perceived problems in the sexually oppressive culture of nineteenth century (Fin de siècle) Germany and offers a vivid dramatisation of the erotic fantasies that can breed in such an environment.[2] Due to its controversial subject matter, the play has often been banned or censored.

Characters

[edit]- Wendla Bergmann: A girl who turns fourteen at the beginning of the play. She begs her mother to tell her the truth about how babies are born but is never given sufficient facts. In the middle of Act Two, Melchior rapes Wendla in a hayloft. She conceives Melchior's child without any knowledge of reproduction. She dies after an unsafe, botched abortion.

- Melchior Gabor: A fourteen-year-old boy. Melchior is an atheist who, unlike the other children, knows about sexual reproduction. He writes his best friend Moritz an essay about sexual intercourse, which gets him expelled from school after the suicide of his friend and the discovery of the essay. His parents send him to a reformatory after his father discovers he has gotten Wendla pregnant.

- Moritz Stiefel: Melchior's best friend and classmate, a student who is traumatized by puberty and his sexual awakenings. Moritz does not understand the "stirrings of manhood" and changes happening to him. A poor student due to his lack of concentration and constant pubertal distractions, he passes the midterm exams at the beginning of the play. However, Moritz is ultimately unable to cope with the harshness of society, and when his plea for help to Fanny Gabor, Melchior's mother, is declined, he dies by suicide.

- Ilse: A carefree and promiscuous childhood friend of Moritz, Melchior, and Wendla. She ran away from home to live a Bohemian life as a model and lover of various painters. Ilse only appears in two scenes throughout the show, and is the last person to whom Moritz speaks before he dies by suicide. She finds the gun he used and hides it.

- Hänschen and Ernst: Two friends and classmates of Melchior and Moritz, who discover they are in love. Towards the end of the play, they confess their love for one another. (In the English translation of the play by Jonathan Franzen, Hanschen is called Hansy, as "Hänschen" is literally the German diminutive form of the name "Hans".)

- Otto, Georg, Lämmermeier and Robert: Schoolmates of Melchior and Moritz. They laugh at Moritz and tease him when he threatens to shoot himself.

- Thea and Martha: The schoolgirl friends of Wendla. Martha has a crush on Moritz and is physically abused by her mother and father. Thea is attracted to Melchior.

- Frau Bergmann: Wendla's mother, who seems to not want her child to grow up too quickly and refuses to tell her daughter the truth about reproduction and sexuality.

- Fanny Gabor: Melchior's mother. Liberally minded and very loving of her son, she protests against sending Melchior to a reformatory as disciplinary action until she discovers that he raped Wendla.

- Herr Gabor: Melchior's father. In contrast to Mrs. Gabor, he believes in strict methods to raise children.

- Sonnenstich: The cruel and oppressive school headmaster who expels Melchior from school upon learning of the essay Melchior wrote for Moritz. His name means “sun stroke” in German.

- Knüppeldick, Zungenschlag, Fliegentod, Hungergurt, Knochenbruch: Teachers at Melchior's school. These names mean "very thick", "accent/manner of speaking" (lit. "tongue slap"), "death of flies", "belt of hunger" and "bone fracture".

- Pastor Kahlbauch: The town's religious leader, who leads the sermon at Moritz's funeral. His name means "bald belly" in German.

- The Masked Man: A mysterious, fate-like stranger who appears in the final scene of the play to offer Melchior hope for redemption. Portrayed on stage by Wedekind himself when the play was first performed.

Plot summary

[edit]Act I

[edit]During an argument over the length of her skirt, Wendla Bergmann confides to her mother that she sometimes thinks about death. When she asks her mother if that is sinful, her mother avoids the question. Wendla jokes that she may one day wear nothing underneath the long dress.

After school Melchior Gabor and Moritz Stiefel engage in small talk, before both confiding that they have recently been tormented by sexual dreams and thoughts. Melchior knows about the mechanics of sexual reproduction, but Moritz is woefully ignorant and proposes several hypothetical techniques (such as having brothers and sisters share beds, or sleeping on a firm bed) that might prevent his future children from being as tense and frightened as he is. As an atheist, Melchior blames religion for Moritz's fears. Before departing, Melchior insists Moritz come over to his house for tea, where Melchior will show him diagrams and journals with which he will teach Moritz about life. Moritz leaves hastily, embarrassed.

Martha, Thea, and Wendla, cold and wet from a recent storm, walk down the street and talk about how Melchior and the other boys are playing in the raging river. Melchior can swim, and the girls find his athletic prowess attractive. After Wendla offers to cut Martha's hair after noticing her braid has come undone, Martha confesses that her father savagely beats her for trivial things (e.g., wearing ribbons on her dress) and sometimes sexually abuses her. The three girls are united by the fact that they do not know why they seem to disappoint their parents so much these days. Melchior walks by; Wendla and Thea swoon. They remark on how beautiful he is and how pathetic his friend Moritz is, although Martha admits finding Moritz sensitive and attractive.

As the boys watch from the schoolyard, Moritz sneaks into the principal's office to look at his academic files. Because the next classroom only holds 60 pupils, Moritz must rank at least 60th in his class in order to remain at school (a requisite he is unsure he can manage). Fortunately, Moritz safely returns, euphoric: he and Ernst Robel are tied academically—the next quarter will determine who will be expelled. Melchior congratulates Moritz, who says that, had there been no hope, he would have shot himself.

Wendla encounters Melchior in the forest. Melchior asks why she pays visits to the poor if they do not give her pleasure, to which Wendla answers that enjoyment is not the point, and after recounting a dream she had where she was an abused, destitute child, Wendla tells Melchior about Martha's family situation. Wendla, shameful that she has never been struck once in her life, asks Melchior to show her how it feels. He hits her with a switch, but not very hard, provoking Wendla to yell at him to hit her harder. Suddenly overcome, Melchior violently beats her with his fists and then runs off crying.

Act II

[edit]Days later, Moritz has grown weary from fear of flunking out. Seeking help, he goes to Melchior's house to study Faust. There, he is comforted by Melchior's kind mother, who disapproves of reading Faust before adulthood. After she leaves, Melchior complains about those who disapprove of discussing sexuality. While Moritz idolizes femininity, Melchior admits that he hates thinking about sex from the girl's viewpoint.

Wendla asks her mother to tell her about "the stork," causing her mother to become suddenly evasive. Anxious, she tells Wendla that women have children when they are married and in love.

One day, Wendla finds Melchior in a hayloft as a thunderstorm strikes. He kisses her, and insists that love is a "charade". Melchior rapes Wendla as she pleads with him to stop, having no knowledge of sexual intercourse or what is happening. She later wanders her garden, distraught, begging God for someone who would explain everything to her.

Despite great effort, Moritz's schoolwork does not improve and he is expelled. Disgraced and hopeless, he appeals to Melchior's mother, Mrs. Gabor, for money with which he can escape to America, but she refuses. Aware that Moritz is contemplating suicide, Mrs. Gabor writes Moritz a letter in which she asserts he is not a failure, in spite of whatever judgment society has passed upon him. Nonetheless, Moritz has been transformed into a physical and emotional wreck, blaming both himself and his parents for not better preparing him for the world. Alone, he meets Ilse, a former friend who ran away to the city to live a Bohemian life with several fiery, passionate lovers. She offers to take Moritz in, but he rejects her offer. After she leaves, Moritz shoots himself.

Act III

[edit]After an investigation, the professors at the school hold that the primary cause of Moritz's suicide was an essay on sexuality that Melchior wrote for him. Refusing to let Melchior defend himself, the authorities roundly expel him. At Moritz's funeral, the adults call Moritz's suicide selfish and blasphemous; Moritz's father disowns him. The children come by later and pay their own respects. As they all depart, Ilse divulges to Martha that she found Moritz's corpse and hid the pistol he used to kill himself.

Mrs. Gabor is the only adult who believes Melchior and Moritz committed no wrongdoing, and that Melchior was made into a scapegoat. Mr. Gabor, however, brands his son's actions as depraved. He shows her a letter that Melchior wrote to Wendla, confessing his remorse over "sinning against her". Upon recognizing Melchior's handwriting, she breaks down. They decide to put Melchior in a reformatory. There, several students intercept a letter from Wendla; aroused, they masturbate as Melchior leans against the window, haunted by Wendla and the memory of Moritz.

Wendla suddenly falls ill. A doctor prescribes pills, but after he leaves, Wendla's mother informs her of the true cause of her sickness: pregnancy. She condemns Wendla for her sins. Wendla is helpless and confused, since she never loved Melchior, and she yells at her mother for not teaching her properly. An abortion provider arrives. Meanwhile, on an evening spent together, Hanschen Rilow and Ernst Robel share a kiss and confess their homosexuality to each other.

In November, an escaped Melchior hides in a cemetery where he discovers Wendla's tombstone, which attests that she died of anemia. There, he is visited by Moritz's ghost, who is missing part of his head. Moritz explains that, in death, he has learned more and lived more than in his tortured life on earth. Melchior is almost seduced into traveling with Moritz into death, but a mysterious figure called the Masked Man intervenes. Moritz confesses that death, in fact, is unbearable; he only wanted to have Melchior as a companion again. The Masked Man informs Melchior that Wendla died of an unnecessary abortion, and that he has appeared to teach him the truth about life in order to rescue him from death. Melchior and Moritz bid each other farewell as the cryptic figure guides Melchior away.

Performance history

[edit]

Due to heavy subject matters such as puberty, sexuality, rape, child abuse, homosexuality, suicide, teenage pregnancy, and abortion, the play has often been banned or censored.[4][5][6]

Anarchist Emma Goldman praised the play's portrayal of childhood and sexuality in her 1914 treatise The Social Significance of the Modern Drama.

Camilla Eibenschütz played Wendla in the 1906 Berlin production.[7] It was first staged in English in 1917 in New York City. This performance was threatened with closure when the city's Commissioner of Licenses claimed that the play was pornographic, but a New York trial court issued an injunction to allow the production to proceed.[8] One matinee performance was allowed for a limited audience.[9] The New York Times deemed it a "tasteless production of a badly translated version [of] the first and most celebrated play by the brilliant Frank Wedekind." The production at the 39th Street Theatre starred Sidney Carlyle, Fania Marinoff and Geoffrey C. Stein.[10] Drama critic Heywood Broun panned the production but singled out Stein as giving "the worst performance we have ever seen on any stage."[11]

There was a 1955 off-Broadway production at the Provincetown Playhouse.[12] It was also produced in 1978 by Joseph Papp, directed by Liviu Ciulei.[13]

The play was produced several times in England, even before the abolition of theatre censorship. In 1963, it ran, but for only two nights and in censored form.[14][4] The first uncensored version was in May 1974 at the Old Vic, under the direction of Peter Hall.[15] The National Theatre Company took a cut-down version to the Birmingham Repertory Theatre that summer.[16] Kristine Landon-Smith, who later founded the Tamasha Theatre Company, produced Spring Awakening at the Young Vic in 1985.[17] The play has been produced in London, in Scotland, and at universities since then.[18]

Adaptations

[edit]The play was adapted into a 1924 Austrian silent film Spring Awakening directed by Luise Fleck and Jacob Fleck, and a 1929 Czech-German silent film Spring Awakening directed by Richard Oswald.

In 1995 English poet Ted Hughes was commissioned by the Royal Shakespeare Company to write a new translation of the play.[19]

National Book Award-winning novelist Jonathan Franzen published an updated translation of the play in 2007.[20] English playwright Anya Reiss wrote an adaptation which the Headlong theatre company took on a tour of Britain in the spring of 2014.[21]

A musical adaptation of the play opened off-Broadway in 2006 and subsequently moved to Broadway, where it garnered eight Tony Awards, including Best Musical. It was revived in 2014 by Deaf West Theatre,[22] which transferred to Broadway in 2015.[23] This production included deaf and hearing actors and performed the musical in both American Sign Language and English, incorporating the 19th-century-appropriate aspects of oralism in deaf education to complement the themes of miscommunication, lack of proper sex education, and denial of voice.[22]

The play was adapted for television as The Awakening of Spring in 2008, under the direction of Arthur Allan Seidelman. It starred Jesse Lee Soffer, Javier Picayo, and Carrie Wiita.[citation needed] In 2008 episodes of the Australian soap opera Home and Away, the play is on the syllabus at Summer Bay High for Year 12 students and causes some controversy.[24] The play was also adapted in 2010 by Irish playwright, Thomas Kilroy, who set the play in Ireland in the late 1940s/early 1950s. This adaptation was called Christ Deliver Us! and played at the Abbey Theatre in Dublin.

References

[edit]- ^ Banham 1998, p. 1189.

- ^ a b Boa 1987, p. 26.

- ^ Bond 1993, p. 1.

- ^ a b Thorpe, Vanessa (31 January 2009). "Banned sex play now a teenage hit". The Guardian.

- ^ "Spring Awakening". The Ohio State University Department of Theatre. Archived from the original on 10 September 2012. Retrieved 10 September 2012.

- ^ Nastasi, Alison (27 October 2011). "The Stories Behind Some of History's Most Controversial Theatrical Productions". Flavorwire (owned by BDG).

- ^ Edward Braun, The Director & The Stage: From Naturalism to Grotowski (A&C Black 1986). ISBN 9781408149249

- ^ Bentley 2000, p. viii.

- ^ Tuck, Susan (Spring 1982), "O'Neill and Frank Wedekind, Part One", The Eugene O'Neill Newsletter, 4 (1)

- ^ "Wedekind Play Abused; Poor Translation and Performance of Fruehlings Erwachen". The New York Times. 31 March 1917. Retrieved 13 February 2018.

- ^ Broun, Heywood (31 March 1917). "In the Play World - Injunction Needed for Poor Production of Gloomy Play by Wedekind". New York Tribune. p. 13. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ Gelb, Arthur (10 October 1955), "Theatre: Dated Sermon; Spring's Awakening Is an Essay on Sex", The New York Times, p. 30

- ^ Eder, Richard (14 July 1978), "Stage: Liviu Ciulei's Spring Awakening; A Director's Play", The New York Times

- ^ Hofler, Robert (1 August 2005). "'Spring' time for Atlantic". Variety.

- ^ Rosenthal, Daniel (2013). The National Theatre story. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 9781840027686.

- ^ "Production of Spring Awakening | Theatricalia". theatricalia.com. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- ^ Companion to contemporary Black British culture. Routledge. 2002. p. 174. ISBN 9780415169899. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- ^ "Spring Awakening | Theatricalia". theatricalia.com. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- ^ Frank Wedekind; Ted Hughes (1995). Spring Awakening. Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-17791-2.

- ^ Frank Wedekind; Jonathan Franzen (2007). Spring Awakening: A Play. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 978-1-4299-6924-6.

- ^ Frank Wedekind; Anya Reiss (10 March 2014). Spring Awakening. Oberon Books. ISBN 978-1-78319-597-8.

- ^ a b Vankin, Deborah (25 September 2014). "Deaf West Theatre makes Tony winner Spring Awakening all its own". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- ^ Isherwood, Charles (27 September 2015). "Review: Spring Awakening by Deaf West Theater Brings a New Sensation to Broadway". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ^ "Christine Jones – Home and Away Characters". Back to the Bay. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

Sources

[edit]- Banham, Martin, ed. (1998). "Wedekind, Frank". The Cambridge Guide to Theatre. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-43437-8.

- Bentley, Eric (2000). "Introduction". Spring Awakening: Tragedy of Childhood. Applause Books. ISBN 978-1-55783-245-0.

- Boa, Elizabeth (1987). The Sexual Circus: Wedekind's Theatre of Subversion. Oxford and New York: Basil Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-14234-7.

- Bond, Edward; Bond-Pablé, Elisabeth (1993). Wedekind: Plays One. Methuen World Classics. London: Methuen. ISBN 0-413-67540-8.

External links

[edit]- The Awakening of Spring: A Tragedy of Childhood by Frank Wedekind at Project Gutenberg, translated by Francis J. Ziegler

- Study guide to the play.

- Spring Awakening at the Internet Broadway Database

- Spring Awakening at the Internet Off-Broadway Database

The Awakening of Spring public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Awakening of Spring public domain audiobook at LibriVox