Weddings in ancient Rome

The precise customs and traditions of Weddings in ancient Rome likely varied heavily across geography, social strata, and time period; Christian authors writing in late antiquity report different customs from earlier authors writing during the Classical period, with some authors condemning practices described by earlier writers. Furthermore, sources may be heavily biased towards depicting weddings of wealthier Roman or portraying a highly idealized image of the Roman wedding, one that may not accurately reflect how the ritual was performed in ordinary life by the majority of Romans. In some circumstances, Roman literary depictions of weddings appear to select the practices included within their portrayal based upon artistic conceit rather than the veracity of those accounts; writers may have intentionally imitated the works of earlier, more famous authors such as Statius or Catullus. For instance, the writer 4th-century poet Claudian frequently notes the presence of pagan deities at the wedding of Emperor Honorius (r. 393–423) and Maria, despite the fact that Rome had already been Christianized by his lifetime and thus most Romans likely had little concern for paganism.

Roman weddings were likely highly religious affairs: the date of the wedding itself was potentially influenced by religious superstition regarding auspicious and inauspicious dates. Prior to the wedding, the auspices may have been consulted to ensure the presence of propitious omens; Roman authors often note the presence of inauspicious signs at doomed or otherwise misfortunate weddings. Sacrifices may also have been performed at Roman weddings, with authors such as Varro noting the presence of pig sacrifices at weddings, although this practice may have been antiquated by the Empire as it unsupported by artistic evidence. Other forms of sacrifice, such the sacrifice of bulls or sheep, are more commonly showcased in artistic portrayals of Roman weddings scenes.

The Roman wedding was centered around a ritual referred to as the domum deductio, a ritualistic kidnapping in which the bride was led from the home of her original family to abode of the groom. This ritual was often described with violent language, with Roman authors emphasizing the fear, suffering, and reluctance of the bride throughout the entire ceremony; they typically mention the bride's tears and blushing, associating her with a sense of shame and modesty referred to in the Latin language as pudor. This was done to convince the household guardians, or lares, that the bride did not go willingly. Afterwards, the bride and the groom had their first sexual experiences on a couch called a lectus. In a Roman wedding both sexes had to wear specific clothing. Boys had to wear the toga virilis while the bride to wear a wreath, a veil, a yellow hairnet, sex crines, and the hasta caelibaris.

Clothing

[edit]Bridal clothing

[edit]Tunics and belts

[edit]

The 1st-century CE writer Pliny the Elder claims that both brides and tirones, new recruits into the Roman army, wore a piece of clothing called the tunica recta. Pliny states that Tanaquil, the wife of the 5th King of Rome Tarquinius Priscus, weaved the first of such tunics.[2] Festus, a 2nd-century grammarian, also mentions that brides and tirones wore a type of tunic, although he refers to the garment as "regillae tunicae" ("royal tunics") and claims that brides wore it alongside yellow hairnets called "reticula lutea." According to Festus, the tunicae were woven by "those standing," possibly referring to the bride herself.[3] The 3rd-century CE Christian apologist Arnobius references a practice in which brides have their togae offered, possibly by themselves or others, to the deity Fortuna Virginalis prior to the wedding; he is the only Roman author to describe the goddess in the context of the wedding. The classicist Karen Hersch suggests that the account of Arnobius may be inaccurate, as his assertions remain entirely unsupported by other pieces of Roman literature; other Roman authors fail to mention such a tradition even when describing the bridal attire. Although Hersch concedes that the remainder of the account of Arnobius is supported by other Roman authors, such as his reference to the bridal lectus ("couch, bed") and the hasta ("spear").[4][5]

The tunic of the bride may have been tied together using a type of belt called the cingulum or the zona, which possibly functioned as some signifier of chastity. In Roman poetry, a belt is sometimes used as shorthand for the either the wedding or the virginity of the bride:[6] Catullus describes a father dishonoring his son's bride by untying her belt and mentions the "zonula," a "little girdle" untied by the brides for the god Hymen.[7][8] Marcus Terentius Varro, a 1st-century BCE Roman polymath, claims that the groom would untie the belt and remain silent for the duration of the task. Festus also describes the presence of a belt in the Roman wedding, claiming that the goddess Juno Cinxia was "sacred" to weddings since the ceremony began with the "unloosing of the belt." The 4th-century BCE Christian theologian Augustine of Hippo also references a wedding belt when he satirically implores the remaining Roman polytheists to replace their many gods with one version of Jupiter worshipped under many epithets, advising the Romans "As the god Iugatinus let him [Jupiter] unite married couples, and when the bride's girdle is loosed let him be invoked as Virginensis."[4][9]

Festus mentions another garment called the nodus Herculaneus ("knot of Hercules"), which Festus claims is untied by the husband whilst the couple is lying in bed. According to Festus, the knot represented the bond between the bride and the groom, claiming that the husband shall be bound to the wife as the tufts of wool are bound together to create the knot.[10] It thus may have served as some variety of love charm for the bride, although was also said—by Festus—to ensure the groom could be as fruitful as Hercules, who had 70 children.[4] Pliny mentions that the knot in a medical context, declaring that binding wounds with the knot "makes the healing wonderfully more rapid" and mentioning an unspecified "certain usefulness" that "is said" to derive from tying a girdle with the knot daily.[11]

Sex Crines

[edit]Festus claims that Roman brides wore a hairstyle referred to within the text as senibus crinibus, an inflected form of either sex crines or seni crines.[12][13] It is possible that "sēnī" is an adjective deriving from the numeral "sex," meaning six. According to this view, the "sēnī crīnēs" likely would have comprised six locks of hair.[14] The 1st-century Roman poet Martial mentions a wife adorned with a septem crinibus.[15] This unusual bridal hairstyle, likely containing 7 locks instead of 6, has been argued—by the classicist Laetitia La Follette—to be an intentional discrepancy used to portray the bride as aberrant and unfaithful.[4] Another possibility is that the word, at least in this context, derives from proposed reconstructions of the Proto-Indo-European verbs "*seh₁-," meaning "to bind," or "*sek-," meaning "cut." If these theories are correct, then it could indicate that the hairstyle involved bounded or cut hair respectively. However, evidence from comparative linguistics strongly suggests that the first reconstruction is inaccurate. The second reconstruction, suggesting that the bride's hair was cut, is incongruent with Roman standards of beauty: long hair was considered to be a component of the ideal feminine physique, indicating that—if the practice of cutting the bride's hair did occur—this ritual would have been shameful for the bride. Other components of the bridal attire functioned to honor the bride in some manner: the tunica recta was woven by the bride herself, showcasing her skill at weaving, and the yellow-red wedding veil—known as the flammeum—symbolized faithfulness and fertility. According to Festus, brides favored the style due to its age; he also stated that it was used by the vestal virgins, lending some credence to the theory that the bridal hairstyle was cut as vestal virgins certainly wore short hair. However, the vestal virgins may have worn a fillet to compensate for their shortened hair, allowing the analogy between the bridal and vestal hair to remain compatible with long bridal hair and short vestal hair.[14] In Miles Gloriosus, a play by the Roman 3rd-century BCE comic playwright Plautus, the author portrays a woman dressed like a standard married Roman woman: her hairstyle is described as having "locks with her hair arranged, and fillets after the fashion of matrons" as part of an effort to disguise the woman as another character's wife.[16] This apparently contradicts the idea of short bridal hair, as Plautus explicitly describes the woman as wearing long hair.[14]

In his description, Festus leaves the proper origins of the sex crines ambiguous: he does not clearly indicate whether the vestal virgins coopted the style from brides or vice versa. Another passage from Festus appears to support the idea that the brides copied the style from vestals: Festus mentions that brides adopted a veil called the flammeum due to its usage by the Flaminica Dialis, the high-priestess of Jupiter and the wife of the Flamen Dialis.[17][18] The similar nature of both these scenarios indicates that, just as bride's may have coopted the flammeum from a religious order, they may have coopted the sex crines. Mary Beard, an English classicist, argued that both vestal virgins and brides embodied a liminal state between youthful virginity and adulthood as a Roman matron; Beard proposed that vestal virgins copied bridal attire due to these shared connotations.[19] American classicist Edward Ross expresses that the sex crines may have merely exemplified the bride possessed the ideal state of virginity and purity which was also demanded of Vestal Virgins. Ross cites a passage from Festus which proclaims not just that brides adorned themselves with the sex crines due, but also that others adopted it from the Vestal Virgins because the chastity of the Vestals "was promised to their men... [sic] by others."[12][20] The German classical philologist August Rossbach argued that the sex crines were a typical component of the attire of a Roman matron, and that brides wore the headgear merely because it marked their transition into marriage and matronhood. Rossbach cited the section of Miles Gloriosus by Plautus, in which the author describes a woman dressed to look like a married woman wearing a hairstyle with fillets modeled after those worn by matrons. The fillets mentioned by Plautus, called "vittae," are not definitively supported by any other evidence to be a component of the bridal hairstyle in ancient Rome. Furthermore, it is unlikely that the crines mentioned by Plautus are the same cosmetic as the sex crines described by Festus. The 1st-century BCE Roman poet Horace utilizes the same word, "crinis," completely unrelated to Roman brides when he describes the hairstyle of the mythical figure of the Trojan War, Paris.[4][21] To reinforce the connection between the bridal hairstyle and the vestal virgins, the number of locks likely present in the hair exactly corresponds to the number of vestal virgins during reliably recorded parts of Roman history: 6. Although, the 1st CE historian Plutarch records that the number of vestal virgins changed from 2 to 4 to 6 during the regnal period.[4]

Hasta caelibaris

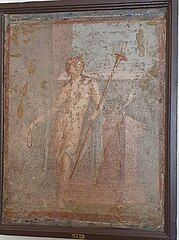

[edit]Festus mentions a spear called the hasta caelibaris ("celibate spear") that was supposedly used in wedding rituals to separate locks of hair.[4] The 1st-century BCE Roman poet Ovid possibly references this spear in his writings when he instructs his female audience to, during the wedding ceremony, let a "hasta recurva" ("bent-back spear") arrange their "virgin locks."[22] Since the ultimate source for Festus' account is the earlier 1st-century BCE author Verrius Flaccus, it is possible unclear exactly how accurately his account reflects Roman practices during both his lifetimes and that of Ovid. If the spear had become an outdated ritual, Ovid may have been intentionally invoking an archaic practice or utilizing a phrase that had become shorthand for the wedding ceremony. Plutarch, a 1st-century Greek philosopher, implies that spears remained involved in Roman weddings during his lifetime: In his Questiones Romanae, Plutarch inquires, "Why do they part the hair of brides with the point of a spear?"[23] Tertullian, a 2nd-century Christian theologian, describes a type of pin called the "acus lascivior" ("lascivious needle") being used to fashion women's hair.[24] Although, it is still not explicitly stated to be a hasta caelibaris used for wedding ceremonies, merely a hairpin used by Roman women.[4] Arnobius mentions the hasta caelibaris by name as an antiquated custom. He attempts to defend the abandonment of pagan traditions and shift towards Christian religion by citing many older, forgotten customs, including the usage of a spearpoint in wedding ceremonies, asking the readers if they still "stroke the hair of brides with the hasta caelibaris?"[5] However, the spear possibly appears in the wedding epithalamium of the 4th-century poet Claudian. During his description of the wedding of two royals, Claudian mentions that the goddess Venus utilizes an acus to split the hair of the bride.[25]

Festus claims that the spear held symbolic value to the Romans, that it displayed the husband's authority over his bride.[4][26] He connects the spear to Juno Curitis, the goddess of marriage and childbirth whose epithet—Curitis—derives from the possibly Sabine word curis, meaning "spear." Evidence from Plutarch provides further support for this association: Plutarch asks if the spearpoint symbolizes "the marriage of the first Roman wives by violence with attendant war." This quote references the rape of the Sabine women, an event from Roman mythology in which the early Romans, desperately in need of a greater female population to ensure continued population growth, abducted Sabine women to marry them and then reproduce. Plutarch also proposes that the violent, distinctly unfeminine (in Roman society) connotations of a spearpoint may have conveyed that the groom was "brave and warlike." He concludes by suggesting a final possibility: that the spear signified that "with steel alone can their marriage be dissolved."[23] The 1st-century BCE Roman historian Livy claims that the Sabine women embraced their newfound husbands and families, suggesting that the spear may have indicated that the bride would similarly submit to her new husband and family.[4] Festus states that the spear must be drawn from the corpse of a gladiator, so that the bride and groom will be joined as close as the spear was to the gladiator.[27] This claim remains unsupported in almost no other text, although the 1st-century CE writer Pliny the Elder mentions that spears drawn from human corpses without touching the ground can be thrown over the house to expedite the childbirth process if the pregnant woman is located inside the aforementioned house. Pliny further states that arrows drawn from cadavers, also without touching the ground, can be placed under the bed of an individual to act as a love-charm.[28] He also attributes magical properties to the blood of gladiators, stating that it can be used as a treatment for epilepsy.[29] These accounts from Pliny imply that the hasta caelibaris may had a similar role as a sign of fertility and a love-charm.[4] It is possible that the hasta caelibaris may have been used to split the locks of sex crines, although there is no explicit connection between the spear and the sex crines with the possible exception of the "acus lascivior" mentioned by Tertullian. Tertullian states that this pin was used to separate the "crinibus," or women's hair.[24] If the hasta caelibaris was connected to the ssex crines, then it remains unclear exactly why no author mentions the item in connection to the Vestal Virgins, who were also linked to the sex crines.[4]

Vittae and Infulae

[edit]Accounts from Propertius, a 1st-century BCE Roman love elegist, suggest that a type of woolen band or fillet called vittae were parts of the bridal attire. In of his poems, Propertius depicts the perspective of a deceased woman named Cornelia on Paullus, her still living husband, stating "Soon, the bordered (toga) yielded to wedding torches, and another altera vitta captured my bound hair, and I was joined to your bed, Paullus, destined to leave it."[30] This passage may be interpreted as referring to Cornelia abandoning her childhood fillets for bridal fillets, or as Cornelia relinquishing her childhood fillets for matronal fillets. Another passage from Propertius details the misfortunes of Arethusa, who laments that their wedding was tainted as her vitta was not placed upon her head properly.[4] The vittae, alongside the stolae, are used in Roman literature as shorthand for the Roman matron. Tibullus, a 1st-century BCE Roman elegist, implores Delia, his mistress, to behave like a proper Roman woman, saying "Teach her to be chaste, although no vitta binds her hair together." Similarly, Plautus describes an incident in which a slave named Palaestrio advised as old man named Periplectomenus to disguise the prostitute Acroteleutium as his wife, instructing him to adorn her with vittae styled after the "fashion of matrons."[31] It is likely that vittae were considered to be representative of chastity and purity: the 4th-century grammarian Servius states that prostitutes were forbidden from wearing the garment and Ovid commands the "chaste" vittae to stay away from his sexually explicit poems.[4][32][33] British-Canadian Classicist Elaine Fantham proposes that the vittae may have offered some variety of "moral protection" comparable to the "bulla," an apotropaic amulet used to protect Roman boys.[34] The vittae are also mentioned as an ornament of the Vestal Virgins: Ovid describes the Vestal Virgin Rhea Silvia adorned with the garment,[35] 4th-century Roman orator Quintus Aurelius Symmachus also describes the Vestal Virgins as decorated with the vittae,[36] the 2nd-century Roman poet Juvenal mentions a priestess wearing the vitta.[37] Two Christian authors, the 4th-century Christian writers Prudentius and Ambrose, also connect the vittae to the Vestal Virgins: Prudentius describes a Vestal Virgin sitting down whilst wearing a vitta and Ambrose describes the "veiled and filleted" head of Vestal Virgins.[38][39][40]

The extent to which vittae were regularly worn by Roman women is disputed. Marcus Terentius Varro, a 1st-century BCE Roman polymath, describes the vittae as an ancient style of Roman dress,[41] although he claims that it was, at one point, a regular component of the attire of a Roman woman. German classical philologist Jan Radicke interprets this past-tense description as a sign that, although the style had fallen out of favor by the time of Varro, it had remained preserved in the cultural consciousness and potentially in important religious ceremonies.[42] However, vittae reappear in the later literature of the Augustan and Early Imperial period as, according to Radicke, an "artificial signifier" of matronal virtue in Roman society that was either "revived or invented" by Emperor Augustus himself. Ovid occasionally refers to the vittae with legalistic language, describing it as an "honor" and mentioning that the vittae protects its wearers "from touch."[43] Radicke interprets this description as referencing either marriage or a possible sacrosanct status of matrons, concluding that the vittae possibly signified that the wearer was a married woman, and thus protected in some manner. Furthermore, in his Tristia, Ovid explicitly defends the legality of his writings, exclaiming "I shall sing of nothing but of what is lawful and of secret love that is allowed. There shall be no crime in my song. Did I not exclude rigorously from reading my Ars amatoria all women whom the wearing of stola and vitta protects from touch?"[44] Such statements from Ovid may be further contextualized by the Augustan Leges Juliae ("Laws of Julia"), which largely concerned the punishment of acts considered by the Romans to constitute sexual immorality. Radicke suggests that, due to this legislation, the vittae may have been a "legal privilege" during the time of Ovid.[42] The 1st-century Latin author Valerius Maximus describes—likely in an almost entirely pseudohistorical manner—an event from the life of Gnaeus Marcius Coriolanus, a legendary 5th-century BCE Roman general, in which the Senate honored various women by offering them vittae.[45] Although this account is almost certainty an inaccurate historical description, it may provide insight into cultural perspectives on the vittae contemporary to Valerius Maximus himself. If this passage does offer such information, then it showcases by the lifetime of Valerius the vittae were offered by the Senate specifically as honorifics.[42]

If vittae were a common component of the attire of Roman women, then it remains unclear why they are largely absent from Roman portraiture. Classicist Susan E. Wood theorized that vittae would have been identified on a sculpture by the colors, as the coloring could differentiate between individual strands of fabric and hair locks.[46] However, the pigment of many Roman sculptures has been lost and thus it is impossible to clearly identify the vittae on any portrait. Elaine Fantham disputes this perspective, arguing that, given the precise detail in many other Roman portraits, it is unlikely that Roman artists would not have meticulously sculpted the vittae in three dimensions.[34] Radicke argues that the vittae, over time, may have lost their social significance and decayed into a more common piece of female clothing in ancient Rome. According to Radicke, the vittae almost entirely disappeared from Roman literature following the account of Valerius, although they appear in the writings of the early 3rd-century jurist Ulpian.[42]

Radicke suggests that there may have been two distinct types of vittae: virginal vittae, the type associated with religious and ritual functions, and the matronal vittae, the kind worn in the outfits of married Roman women. In literature from the early Imperial period onwards, the virginal vittae often appear in a mythological context, usually with some connection to virgin goddesses: Ovid mentions that the virgin goddess Phoebe had her hair bound by a vitta and that the nymph Callisto was adorned with a white vitta, Vergil describes them in connection to the goddess Vesta and the Vestal Virgins in the Aeneid, and Horace mentions that the Roman noblewomen Livia and Octavia wore the vittae during a ritual procession commemorating Augustus' return from military campaign in 24 BCE.[42] Pliny the Elder mentions that a "white vitta" was used to wrap around a "garland of spikes,"[47] also providing evidence for a potential etymological connection between the word "vitta" and the Latin verb "viere," meaning "to twist, to plait."[42] The matronal "vittae" is described as "tenuis," or "narrow," by Ovid.[33] In the early 3rd-century BCE, the Roman jurist Ulpian mentions vittae ornamented with pearls.[48]

According to Servius, vittae hung from the sides of another—potentially bridal—adornment: a red and white band-like crown called the infula.[49] Servius provides additional descriptions of the infula, stating that they were worn like diadems and made from white or scarlet threads.[34] Infula were connected to religious Rituals in ancient Rome: Festus claims they were a wool thread used to drape priests, temples, and sacrificial victims.[34][50] Both infulae and vittae may have been used to consecrate both inanimate and animate objects. In a wedding poem authored by the 1st-century CE poet Statius, the goddess Juno gives the vittae to a bride and Concordia sanctifies them.[4][51] In the Aeneid, Helenus is said to have removed his vittae after he was finished sacrificing oxen.[52] Infulae appear much more frequently in standard literature than vittae, which are more common in poetry: the word infula appears only twice in the Aeneid while 1st-century BCE historian Livy mentions it often. At one point in his work Ab urbe condita, Livy describes diplomats from Syracuse came to Rome adorned with infulae. Fantham argued that this discrepancy regarding the usage of infulae and vittae between poetry and other works emerged as the limitations of dactylic verse permit only the nominative singular form of infula, making vitta a much more practical word to use for poetic purposes. Thus, Fantham concludes that Roman poets may have substituted the infula for vitta for poetic convenience. Fantham cites a line from the Epistulae ex Ponto of Ovid in which he mentions an "infula" that is replaced by the word "vittis" in the next line.[34][53]

In his epithalamium for Peleus and Thetis, Catullus mentions an adornment called the filum. Within the poem, the Parcae predict that, following the wedding, the filum will no longer be worn around that bride's neck. It is possible that this metaphorically represented the loss of virginity upon the wedding day, and therefore it may be connected to the vittae due to their shared chastity connotations. Another possibility is that the filum was connected to girlhood in Roman culture, and therefore it was abandoned following the wedding and transition to adulthood. Otherwise, it may have been an entirely meaningless piece of clothing, and the main focus of the passage is actually on the nurse of the bride.[54]

Flammeum

[edit]

The flammeum, a type of bridal veil, was a staple component of the bridal hairstyle in ancient Rome.[56] During the 1st-century, the Roman author Catullus continues to utilize the term flammeum to refer to both the covering and the bride: in Catullus 61, he instructs children to "Raise high, O boys, the torches: I see the gleaming veil approach."[57] In the Epigrams of Martial, the author utilizes the weaving of the flammeum as shorthand for the entire wedding ceremony, stating "The veils are a-weaving for your fiancée, the girl is already being dressed."[58] In another one of his epigrams, he describes the wedding of two men named Calistratus and Afer, stating that Callistratus weds exactly like the virgin brides of traditional Roman weddings.[59] To further emphasize his point, he mentions that he wears the flammeum, is accompanied by torches, and by the rude songs found in Roman wedding ceremonies.[4][60]

The covering is mentioned throughout Roman literature, from its mention in the works of the 2nd-century BCE Celtic-Roman poet Caecilius Statius to the time of 4th-century CE during the time of Claudian. Pliny the Elder refers to the veil as "antiquissimus" (meaning "very old"), claiming that the color luteus was held in high regard during these ancient times and was thus reserved for bridal veils.[61] Similarly, Festus cites two ancient authors called Cincius and Aelius, who—according to Festus—claim that the "ancients" (antiqui), call the practice of covering the bride's head with the flammeum "obnubere," or "the veiling."[62][42] Jan Radicke argues that the flammeum likely remained in use by the lifetime of Catullus as it retained a strong sense of prominence in his poems, although he concludes that by the Augustan era the garment had fallen out of fashion. Literature from the Early Imperial era makes little reference to the garment; for instance, it is absent from Statius' wedding epithalamium for Lucius Arruntius Stella. The 1st-century CE Roman poet Lucan describes the functions of the flammeum, although Radicke interprets this as a historical account of a traditional Roman headdress, not a contemporary account of a piece of clothing that remained in use by the lifetime of Lucan. According to Radicke, later references to the garment are better explained as intentional invocations of an ancient practice designed to portray the individuals involved as staunch traditionalists.[4]

Lucan mentions that the flammeum was used to conceal the blushing of the bride; he claims that during the wedding of a woman named Marcia, who lacked this veil, it was not present to disguise her "timid blushes."[63] Improper, or "worn-out" flammea are usually mentioned in Roman literature alongside immodest, unvirtuous wives. Juvenal mentions that a woman has remarried many times "flies from one home to another, wearing out her bridal veil."[64] The 2nd-century writer Apuleius disparages the wife of a man named Pontianus, saying that she has been deflowered, shameless, and wearing a worn-out veil.[4][65] Festus mentions that, since the garment was also worn by the Flaminica Dialis (the priestess and wife of Jupiter), it was viewed as an auspicious charm designed to bring good fortune.[66] Since the Flaminica was unable to divorce Jupiter, it is possible that the flammeum was worn by brides as a protective charm against divorce or ill fortune in marriage. Another possibility is that the Flaminica was viewed as a perpetual bride, henceforth she permanently wore the bridal headpiece.[4]

The precise color of the flammeum is unclear, Lucan claims that it was of the luteus color and that it was used to shield the bride's shame and blushing, or pudor. This implies that either the veil was red, thus concealing the reddish blushing, or that it was thick enough to hide the skin underneath. The interpretation of the flammeum as red is supported by a later scholiast of Juvenal, who describes the veil as sanguine and resemblant of blood. However, Pliny the Elder, who stated that the color luteus was often used for bridal veils, compares this color to egg-yolk as luteum, implying that the color may have been orange-yellow shade. Festus mentions that the flammeum was worn by the Flaminica Dialis, the priestess and wife of Jupiter. He claims that the covering was the same color as the lightning of Jupiter, indicating that it was much closer to a yellow color than a red shade. Luteus is also used as an adjective for the bride, not just the flammeum: Catullus describes a bride whose face is "luteus as a poppy." Such a description conforms to a trend in Roman literature of depicting the blushing of the bride, as well as a general lack of yellow poppies, although only if it is assumed that the color luteus is reddish. Classicist Robert J. Edgeworth concluded that the word luteus may mean either pink or yellow depending upon the context.[4]

Evidence from Roman literature suggests that the veil either entirely or almost entirely masked the bride's appearance: In the play Casina by Plautus, the plot requires that a male slave be effectively disguised as a female bride and Ovid describes a myth in which the god Mars is tricked into wedding the goddess Anna Perenna under the impression that he was marrying Minerva. However, wedding depictions in Roman artwork typically portray the faces of the brides uncovered, possibly because the artists wanted to ensure the viewers could recognize their faces or due to difficulty depicting a translucent material. Two examples of sarcophagi from the around 180 CE depict brides with their veils drawn so far back that their hair is visible. However, another sarcophagus dating to 170 CE shows the bride with her veil pulled forwards and her head tilted downwards, possibly in a submissive pose; her face is visible, although not as clearly as the other sarcophagi. Wedding scenes from a sarcophagus dated to 380-390 CE portray a bride with a towering veil; the veil is large enough to make her appear taller than her husband, presumably because it covers an intricate bridal coiffure underneath. One of the scenes from this sarcophagus portrays the woman with a cloak covering each shoulder and, like the other sarcophagi, drawn over the base of her throat.[4]Jan Radicke argues that many artistic depictions portray the flammeum not as a veil, but as instead a "bridal scarf." For instance, a sarcophagus from Mantua portraying the story of Medea depicts Creusa, the bride of Jason, wearing a scarf that falls back on her head and covers the shoulders. Another Roman wedding depiction, this time from a late-Republican gravestone for Aurelia Philematium and her husband, portrays the bride with a scarf attached to her hair. In the Villa Imperiale, a fresco depicts a woman that may tentatively identified as the bride with an orange scarf. He further cites a passage from the 2nd-century BCE Roman author Caecilius Statius: "That yesterday he'd looked in from the roof, had this announced, and straight the flammeum was spread."[67] In this passage, the flammeum is displayed within the house to signal that the wedding is going to occur soon. Radicke argues that it is more likely that the Romans would display a larger scarf rather than a small veil. Radicke cites another passage from Catullus in which the author describes the god Hymen—presumably—dressed like a bride. Catullus states that Hymen wears both the flammeum, and has their head covered by a wreath made from marjoram.[42]

Wedding Crowns

[edit]Festus mentions that Roman brides wore a piece of headgear called the corolla, a crown made of herbs, flowers, and foliage personally handpicked by the bride.[68] This account is supported by artistic evidence: the "Sarcophagus of the Brothers," an ancient Roman sarcophagus stored in Naples, depicts a ceremony in which a woman identified as Venus crowns either a bride or an already married wife with a garland of flowers. Other accounts of wreaths in other Roman depictions of wedding ceremonies portray the corolla as a piece of groomal attire: Plautus and Apuleius both mention grooms wearing crowns of an unspecified material and Statius depicts a groom with a crown made from roses, lilies, and violets.[4] Another "towering crown" called the Corona Turrita, which is exclusively mentioned in the works of Lucan,[69] is attested for as bridal gear by a later scholiast commentating upon his works. Whereas the original text only mentions a matron bedecked with the Corona Turrita, the scholiast refers to this individual as a bride. Baltic German archaeologist Hans Dragendorff argued that this type of crown connected to an ancient tradition of depicting goddesses such as Aphrodite or Astarte with large pieces of headgear. Dragendorff cites the 1st-century BCE Roman scholar Varro, who described the goddess Hera in bridal clothes; he also invokes a passage from Synesius, a 4th-century Greek bishop who claimed that brides wore crowns like those that adorned the goddess Cybele. Furthermore, Dragendorff proposed that these depictions, if not accurately reflective of Roman bridal gear by the lifetime of the authors, likely were distant memories of an ancient Italian-Greek bridal custom. Although the commentary of the scholiast indicates that the garment was indeed bridal gear, Karen Hersch rejects this analysis. Hersch argues that the interpretation of the scholiast is likely inaccurate as Roman authors never refer to a bride as a matrona and that it is unlikely Lucan would utilize the terms matrona and nupta interchangeably to describe the same character. Furthermore, there are no other instances of a "Corona Turrita" occurring as a bridal instrument in Roman literature. Hersch also rejects the proposal of Dragendorff, arguing that there is not sufficient evidence to connect goddesses such as Cybele to wedding rituals.[4]

By the 4th-century, Christian art depicting weddings often portrays Christ offering crowns to the wedding couple; this practice was heavily criticized by contemporary Christian authors, who viewed it as a custom marred by pagan traditions. Tertullian argues that marriage "decks the bridegroom with its crown; and therefore we will not have heathen brides, lest they seduce us even to the idolatry with which among them marriage is initiated."[70] However, such texts also imply that the practice was popular amongst Christians: Tertullian opens his essay, De Corona ("On the Crown"), by describing a situation in which Christian soldiers were offered laurel crowns, and only one refused. Furthermore, he declares that the intention of his writing was as an invective against "the laurel-crowned Christians themselves."[71] Tertullian was not alone in his sentiments, the 2nd-century Christian theologian Clement of Alexandria and the 3rd-century writer Minucius Felix both condemn the practice: Clement expresses that "The use of crowns and ointments is not necessary for us; for it impels to pleasures and indulgences, especially on the approach of night" and Felix, writing from the perspective of a fictional character named Octavius, responds to the accusation that Christians refuse to adorn their heads with flower garlands due to their fear of the pagan Gods by stating "Pardon us, forsooth, that we do not crown our heads; we are accustomed to receive the scent of a sweet flower in our nostrils, not to inhale it with the back of our head or with our hair."[72][73] It is possible, however, that the perspective of these authors was outdated by the 4th-century, with the fears of paganism or idolatry associated with these customs dissipating over time. Gregory of Nazianzus, writing in the 4th-century, advises the bishop Eusebius to, during a wedding, allow the father—possibly the father of the bride—to "impose the crowns." John Chrysostom, the Archbishop of Constantinople in the 4th-century, claims that the wedding garlands functioned as "symbols of victory" that signify that the bride and groom are able to "approach the marriage bed unconquered by pleasure.[74] The scholar Mark D. Ellison suggests that the prevalence of crowns in Christian nuptial rites may be connected to associations between crowns and temperance in the New Testament, with Paul mentioning that "every one that contends for a prize is ἐγκρατεύομαι ["enkrateúomai," "temperate, also used in a sexual context"] in all things: they indeed then that they may take a corruptible στεφᾰ́νου ["stéphanos," "crown"], but we an incorruptible."[75] Ellison further cites other sections from the New Testament which references crowns of, according to him, "eternal reward:" for instance, the "στέφᾰνος ["stéphanos"] of righteousness" mentioned as a reward the Second Epistle to Timothy.[76] Although the sources often indicate a connection between sexual moderance and the crowns, Ellison argues that this iconography instead functions to publicly display the couple's religious merit, thereby depicting them as "spiritual victors."[77]

Groomal clothing

[edit]There is limited information regarding the groomal attire as Roman authors tended to focus on describing the bride, leaving only scant descriptions of groomal clothing available to modern scholars. Whereas the bride is often identifiable due to various pieces of clothing, such as the flammeum or sex crines, the groom is never recognized by their choice of garb. Classicist Karen Hersch assumes that the groom likely wore clean clothes, "probably a toga if he owned one," however Lucan mentions that Cato the Elder maintained an "untended beard" during his wedding.[78] This dearth of detail could represent the difference between the symbolism of the wedding ceremony for the bride and the groom: the wedding seemingly functioned as a coming-of-age ritual for the bride, but likely lacked such significant symbolism. It is possible that, for a Roman boy, their coming-of-age ceremony occurred before the wedding, when they relinquished their bulla and toga praetexta, and donned their toga virillis. Boys usually started wearing togae virilles around puberty, or when the boy's parents believed he was sexually mature.[3] The bulla was dedicated to Lares, household spirits and guardian deities in Roman religion.[3] Arnobius describes a practice—which supposedly occurred long before the life of Arnobius—in which Roman girls surrendered their togulae (or "little togas") to Fortuna Virginalis before the wedding. The epithet "Virginalis" is exclusively given to Fortuna by Arnobius. Another, similar practice is mentioned by the 1st-century Roman poet Persius, who describes Roman girls offering their dolls to Venus.[79] In another account by a scholiast of Persius, it is mentioned that this practice occurred an unspecified amount of time prior to the wedding.[4] Pseudo-Acro, a scholiast of the poet Horace, mentioned a custom of girls and boys dedicating their bullae and dolls respectively, although he claims the items were offered to the Lares and makes no mention any connection with the Roman wedding.[4][22]

Customs

[edit]Ideal Bride and Groom

[edit]The Roman wedding was designed to ensure the legitimate transfer of the bride into a legal marriage. In Rome, the ideal bride was supposed to lack prior sexual experience and be simultaneously frightened and joyful about the upcoming wedding. Depictions of the Roman wedding emphasize the misery and fear of the bride; literary accounts sometimes describe the tears and blushes beneath the bridal veil and artistic portrayals depict brides with turned town faces or eyes. Catullus, a 1st-century BCE Latin poet, describes the bride as "eager for her new husband," but also as sobbing because "she must go."[80] In an epithalamium by the 4th-century CE poet Claudian, the bride is explicitly commanded by Venus to love her husband despite her initial fear of the wedding: Venus instructs her, "whom you now fear you will love."[81] The imagery of a suffering bride may have exaggerated for artistic purposes, although it is also possible that real Roman brides did indeed feel significant discomfort as the wedding marked a transitory period in their lives in which they were separated from the family figures.[4] However, marriage was a pivotal time in the lives of Roman women; there was tremendous social pressure to become married and women were raised with this pressure surrounding them. Thus, it is possible that Roman women in reality faced little sadness at the thought of the wedding ceremony as it was a normalized aspect of Roman culture.[4] Catullus himself appears to recognize the sorrow of the bride as insincere, exclaiming that "Their groans are untrue, by the gods I swear!" and asking if "the parents' joys turned aside by feigned tears, which they shed copiously within the threshold of the bedchamber?"[82] Wasdin argues that Roman literature often fetishizes the idea of resistance to sex or a feigned unwillingness to partake in intercourse: Ovid states "Perhaps she will struggle at first, and cry “You villain!” yet she will wish to be beaten in the struggle."[83] However, Wasdin argues that the violence is justified within Roman literature by the supposed artificiality of the bride's dismay, noting that in other pieces of Roman spousal violence is explicitly condemned:[84] Tibullus exclaims that he "would not wish to strike thee, Delia [his lover], but if such madness come to me, I would pray to have no hands."[85]

Little attention was paid to the autonomy or will of the bride in Roman wedding rituals: Catullus instructs the bride to avoid displeasing her husband, stating "You also, bride, what your husband seeks beware of denying, lest he go elsewhere in its search."[80] In another section of the Carmina of Catullus, a bride is told to obey their husband as her father has arranged the marriage, and that rightful ownership of their virginity is split in thirds between their father, mother, and themselves.[80] Catullus utilizes a litany of floral or natural metaphors to describe the bride and the wedding couple, portraying the bride as "shining with a florid face" ("ore floridulo nitens") and appearing like a "yellow poppy" ("luteumve papauer") and a "white chamomile" ("alba parthenice"). Classicist Vassiliki Panoussi argues that such depictions impart a sense of intimacy, passivity, and vulnerability onto the bride, citing in particular the use of the diminutive "floridulo" and the connection between the term "parthenice" and the Greek word "παρθένος" ("parthénos," "maidenly, chaste"). In another part of the text, the bride is equivocated to a hyacinth in the garden of a rich man. Panoussi interprets these portrayals as a form of objectification of the bride, reducing her to a piece of ornamentation utilized to display the splendor of her husband's household, the same way the flower is used to decorate the garden. Furthermore, Catullus emphasizes the supposed power and prestige of the groom's home, describing the abode as "powerful" ("potens") and "prosperous" ("beata").[7][86]

Catullus continues the floral metaphors, emphasizing the bride's affection for the groom by comparing her to ivy, stating "as the soft vine enfolds the nearby trees, he will be enfolded in your embrace." The notion of the wedding as the precursor to an ultimately felicitous union is upheld by the chorus of boys in Catullus 62, who—while disputing the merits of marriage with a chorus of girls—compare the wedding to joining a plant with an elm, thereby enhancing the plant's fertility and permitting it to benefit from the "ripest of seasons." Although the girls liken the wedding to destroying said flower, the chorus of boys states that, by this procedure, the bride becomes dearer to the groom and less hateful to her father.[87] However, Panoussi argues that these poems imply that the supposed fortunate of the union was contingent upon the submission of the bride to male authority: the marriage contracts noted in the text are signed exclusively by men and the boys are unconcerned with the feelings of the bride, citing only that her husband and father will approve of the union.[86] Panoussi states that the bride likely could retain some degree of agency through the importance conferred onto her by Roman social expectations: Catullus states that a virtuous Roman matron proves the value of their overall family ("genus"), that a bride is vital to produce the offspring needed to continue a family lineage, and he laments that without the bride assuming her role as a matron, then they could not give birth to children who could one day become soldiers and thus help uphold the Roman Empire.[7] Within this framework, Panoussi argues that—at least within the poetry of Catullus—the conflict between the unpleasant nature of the wedding and its importance for overall society can be interpreted as an internal conflict between societal demands and personal aspirations, a conflict between the bride's desire to avoid such unpleasantness and their perceived calling within Roman culture to accept the responsibility of matronhood.[86]

The ideal Roman groom was in many ways the opposite of the ideal bride: they were supposed to be both desirous of the wedding and sexually experienced.[88] Statius, in one of his epithalamia, mocks Stella—the groom—for failing to act upon his love for Violentilla and take her as his bride, stating "Sigh no more, sweet poet, she is thine. The door lies open, and thou can come and go with fearless step."[89] Catullus describes the groom as trembling during the wedding ("tremens"), however he also mentions that the groom listens to the ceremony with an "eager ear" ("cupida aure"). The writings of Catullus portray the groom as more sexually violent and aggressive, utilizing the term "immineat" ("to threaten" or "to long for") to describe the groom lying in bed awaiting the bride; he further mentions that the groom's "passion" ("flamma") burns brighter than that of the bride.[7][86] Claudian compares Honorius and his passion for his bride, Maria, to that of a sexually aroused horse, stating that Honorius was akin to "noble steed when first the smell that stirs his passions."[90][91] Differing cultural attitudes towards the groom and the bride are reflected in the Latin language itself: brides were said to "nubere viro," or "to veil [themselves] for a man," while grooms were said to "ducere uxorem," or "to lead a wife."[4]

Auspices and Sacrifices

[edit]

The taking of omens was possibly a necessary, or at least highly preferred, part of the Roman wedding. When describing wedding ceremonies, Roman authors frequently note either the presence of favorable omens or augurs at a wedding ceremony. For instance, Catullus describes an individual named Manlius wedding a virgin named Vinia while blessed by good omens and describes the Fates themselves offering prophecies at the wedding of Peleus and Thetis.[92][93] Conversely, authors often describe the lack of such boons at doomed or improper weddings. In the Troades of Seneca, Helen of Troy laments that any wedding "bred of evil fate" and "full of joyless omens" is deserving of her "baleful auspices."[94] Servius wrote that the thunder and lightning present at the wedding of Aeneas and Dido signified that their union would be unfortunate.[95] In his Metamorphoses, Ovid writes that a screeching owl appeared at the wedding of Tereus and Procne, presumably signifying the impending transformation of Procne and Philomela into birds.[96]

Cicero, writing in the 1st-century BCE, describes the practice of utilizing augurs and diviners at weddings as if it had already become antiquated by his lifetime, mentioning that, although augurs still appeared in Roman weddings, they lacked the same religious significance.[4][97] Other writings of Cicero imply that augurs or other officiating priests remained pivotal to the Roman wedding: he lambasts an individual named Sassia for marrying her son without anyone "to bless" or "to sanction the union" and amidst "nought but general foreboding."[98] Valerius Maximus, a 1st-century CE Roman rhetorician, also reinforces the dated nature of augurs at Roman weddings, stating "Amongst the ancients nothing, either private or public, was held without auspices consulted."[99] In his description of the various illegitimate weddings of Messalina and Nero, the 1st-century CE Roman historian Tacitus highlights the ritualistic taking of the auspices, possibly as part of an attempt to convey the debauchery of these figures. His account is almost certainly inaccurate as a piece of historical documentation; however, his writing may accurately reflect and convey the cultural values of his time, thus rendering it somewhat useful to modern historians.[4] Whilst describing Nero as a licentious individual, Tacitus mentions that the emperor, alongside performing other components of the wedding ritual, also observed the auspices during his wedding to the freedman Pythagoras, in which Nero appeared as the bride.[100] At the wedding of Messalina and Gaius Silius, Tacitus also mentions that they performed all the traditional rites of a Roman wedding, including the consultation of the auspices.[101] Classicist Karen Hersch hypothesizes that Tacitus may have been infuriated that these individuals choose to include all the elements of a legitimate wedding within their own, in his opinion, perverted ceremonies. Hersch further suggests that, assuming the rituals were indeed antiquated by the time of Tacitus, he may have been illustrating the eccentricity of these figures by describing them utilizing an ancient practice. Alternatively, as Tacitus more specifically states that Messalina had heard the words of the auspex, Hersch suggests that Tacitus may have been attempting to imply that she was failing to heed dire omens. Juvenal similarly satirizes the wedding of Messalina, claiming that she attempted to emulate a legitimate marriage by bringing along witnesses, an augur, and a wedding dowry of one million sesterces in the "ancient fashion."[102] It is possible that Juvenal's emphasis on the "ancient fashion" is intended to induce outrage at a perceived defilement of the mos maiorum, or the customs and traditions of ancient Rome.[4]

Varro claims that the "ancient kings" and "eminent persons" of the Etruscan civilization sacrificed pigs to sanctify treaties, including wedding rites. Varro believes that this custom was also adopted by the Latin tribes and the Greek inhabitants of Italy, and that remnants of this custom persisted in the usage of the term "porcus" as a slang term for female genitalia.[103] Hersch argues that nuptial pig sacrifices may have ceased to occur by the early Empire due to lack of any artistic evidence for such a custom, despite the plethora of depictions of bulls and sheep on wedding scenes from sarcophagi. Servius, writing in the 4th or 5th centuries, treats the custom of animal sacrifice as an antiquated custom, claiming that "amongst the ancients no wife was able to be wed nor field able to be plowed without the sacrifices completed."[104] Another reference to pre-nuptial animal sacrifice derives from the Aeneid: Queen Dido, prior to her wedding, attempts to acquire assistance from various deities by—in isolation—pouring a libation between the horns of a white cow and sacrificing sheep to Apollo ("Phoebus"), "lawgiving Ceres ("legiferae Cereri")," the "father Lyaeus ("patrique Lyaeo")," and, most importantly ("ante omnis"), Juno, who governs marriage bonds ("cui vincla iugalia curae").[105] Karen Hersch states that the precise details of Dido's involvement in this sacrifice remain unclear: Dido possibly personally scarified the animals, although the text also allows for the interpretation that she instead let priests perform the deed for her. Hersch proposes that Virgil may have intended to emphasize the "foreignness" of Dido, perhaps hoping to communicate that no Roman woman would similarly engage in a sacrifice. Alternatively, Virgil may have wished to emphasize the "doomed" nature of her wedding by showing Dido partake in an improper ritual. Sheep specifically are mentioned as part of the wedding ritual by Plutarch, who claims that, upon introducing the bride, the Romans would lay a fleece underneath her and then the bride would proceed to hang a thread of woolen yarn from her husband's door using a distaff and a spindle.[106] However, in the Roman play Octavia, a bloodless sacrifice of material possessions is depicted, in which Poppaea Sabina, the second wife of Nero, coats an altar in wine and offers incense to unspecified gods.[107] Other evidence from Roman literature indicates that the groom was primarily responsible for wedding sacrifices: In The Golden Ass of the 2nd-century writer Apuleius, a character called Tlepolemus travels through the city accompanied by his relatives to sacrifice at public shrines and temples prior to his wedding.[108] Another account of a pre-nuptial sacrifice performed by the groom derives from the play Hercules Oetaeus by Seneca: In the play, Deianira—the wife of Hercules—becomes enraged upon hearing that Hercules would take another woman, Iole, as a new wife and prays to become the sacrificial victim, hoping that Hercules would kill her and that her corpse could fall upon the lifeless body of Iole.[109]

Auspicious and Inauspicious dates

[edit]Roman authors recorded numerous dates in which it was considered ill-omened to wed; however, Hersch argues that such religious rules may not have necessarily concerned all, or even the majority, of Roman citizens. Hersch considers it unlikely that each individual Roman had detailed knowledge of the calendar, suggesting that—for most Romans—the intricacies of the calendar may have been inscrutable. Furthermore, Hersch argues that it is unlikely the Roman populace unanimously avoided performing any task on the days which Romans authors considered unlucky. Individual Romans would—according to Hersch—have been differently affected by religious matters; for instance, an urban resident in Rome may not have been concerned with agrarian omens. Many sources for these traditions were intentionally archaizing and thus may reflect traditions which had become antiquated by the author's lifetime: writers such as Ovid sought to catalogue the mythological origins for parts of Roman society and authors such as Varro and Festus were documenting rare and obscure words in the Latin language.[4] Augustine critiques the entire notion of attempting to predict ill-fortune depending upon the wedding date, decrying the affair as "foolishness" ("stultitiam singularem") because—according to Augustine—individuals cannot change their destiny.[110]

Macrobius. a 5th-century Roman historian, suggests that the Calends, Ides, Nones, and the days following the Nones, ought to be avoided for weddings because violence was forbidden on the dates—according to Festus,[111] because Republican military leaders had suffered catastrophic defeats after supplicating the gods on these dates—and violence appeared to be committed against virgins during the wedding. Varro, according to Macrobius, stated that these dates, alongside any day of religious observance ("feriae") were more favorable for the weddings of widows than virgins because it was considered more favorable to clean out old drainage ditches than dig new ones during these days.[112] Days associated with death were considered unlucky days for a wedding: the days of mundus patet ("the world is open"), in which the spirits of the dead ("manes") were believed to walk the earth; the Parentalia, in which feasts were held in honor of the dead; and Lemuria, in which the Romans performed rituals to excise malevolent spirits of the dead from their homes, were all considered inauspicious for weddings. Ovid claims that women who wed during the Lemuria festival were expected to not live much longer and that the general public of Rome, the vulgus ("common folk"), believed that "bad women" ("malas") wed in May due to its connections with the festival.[113] Other holidays are mentioned as inhospitable for weddings: Plutarch states that men refused to wed throughout the entire month of May, a tradition that is possibly connected to Lemuria or the festival of the Argei, both of which occurred in May. Plutarch alternatively proposes that men wished to delay the wedding until June because the month was considered more favorable for weddings due to its connections with Juno.[114] Ovid mentions that they were ill-advised on the festival of the Salii, who were priests of Mars, due to the presence of weapons at the festival and because "fighting is unsuitable for marriage."[115] There is only scant evidence for any propitious wedding dates. Ovid mentions that the Ides of June was advantageous ("utilis") for brides and bridegrooms although the "first part" of the month was considered unpropitious ("aliena") for couples because—according to the Flaminica Dialis in a conversation with Ovid—these dates occur before the Vestalia had concluded, thus occurring before the Temple of Vesta was cleaned and while Flaminica was still forbidden from cutting her nails with iron, combing her hair with a comb made from boxwood, or touching her husband the Flamen Dialis. The Flaminica concludes by advising Ovid that his daughter "will better wed when Vesta’s fire shall shine on a clean floor."[4][116]

Domum Deductio

[edit]

The Roman wedding incorporated a ceremony called the "domum deductio" ("leading to the home"), which functioned as a ritualistic public kidnapping of the bride from her home to the house of the groom, possibly intended to demonstrate the wealth and prestige of the families involved as well as provide conclusive proof that the wedding had occurred.[117] According to Festus, the ceremony involved seizing the bride from her mother's "gremium" (meaning either "lap" or, figuratively, "embrace"), or—if her mother was not present—the next closest female relative, and then transferring her over to the groom.[118] This claim is further substantiated by accounts from Claudian, who describes the bride Celerina also being pulled from her mother's "gremium" by the goddess Cytherea, another name for Aphrodite.[119] It is unclear at precisely which time the taking of the bride occurred: the groom is not mentioned accompanying the bride on her journey to the new house, leading Hersch to propose that the seizing did occur until the bride had already arrived at the home of the groom. Hersch supports her interpretation with a passage from Catullus in which he describes Hesperus, the evening star (which itself is the planet Venus in the evening), stealing the bride from her family.[87] The bride was expected to at least feign fear of the wedding ceremony and despondency at the prospect of marriage. Hersch argues that by demonstrating a reluctance to abandon their homes, the bride was signifying that they had, prior to the wedding, "lived a cloistered life among her female relatives" and therefore was a chaste bride suitable to become a wife. Hersch cites the lack of the bride's "father or male guardian" at the seizing of the bride, which—in Hersch's opinion—reinforced the absence of men from the bride's life and consequently her virginity.[4] Hersch further proposes that since the flammeum likely either completely or almost completely veiled the bride's face, they may have been forced to convey their discontent through mime—more specifically, Hersch suggests such performance could have included loud crying, hanging the head dejectedly, and walking with visible trepidation. The overall purpose of this ritual—according to Hersch—was to reinforce a sense that the bride was in some way alienated from the family of the groom, that they were a permanent outsider only brought into the new family by force. Hersch argues that this cultural attitude is further reflected by the conventions of Roman nomenclature, according to which girls were not obligated to adopt the name of their husband; Hersch suggests that, collectively, these practices served to establish a sense of separation between the bride and the groom's family.[120]

Macrobius notes that, during weddings, maidens were most vulnerable to suffering violence; he describes this violence with the word "vim" (meaning "force" or "assault"),[121] a term which is also used by the 1st-century Roman historian Suetonius to describe the wailing and lamentation of Nero, who, during his wedding to the slave Doryphoros (who is himself potentially identical to Pythagoras), was attempting to imitate the cries of "suffering virgins."[122] Furthermore, this term was connected to the notion of forceful sex, or rape, in various Roman writings, with the author Augustine etymologically connecting the name Venus to the violence of Roman wedding ceremonies, declaring that Venus is called as such because "without violence ("sine vi") a woman does not cease to be a virgin."[123] Physical violence is described in the play Casina, in which the slave Olympio notes that when he entered the bedroom with the bride. who is the slave Chalinus disguised as Casina, Chalinus physically assaulted him by kicking him off the bed and then pummeling his face.[124] Despite the extreme reaction, Hersch notes that the groom does not find this behavior incongruent with that of an actual bride; he remains convinced that Chalinus is in fact Casina.[120] Furthermore, the scholar Judith P. Hallett noted that—during this same bedroom scene in Casina—Olympio mentions that the bride blocked one "entrance," leading him to ask the bride to "let [him] enter through the other [one]."[125] Hallett interprets this scene as referring to anal sex, which Hallett suggests may have been preferred by brides as it reduced the risk of injury to their bodies. Hallett cites another instance of a similar description from the Carmina Priapeia, a series of short poems dedicated to the god Priapus thought to have been composed during the 1st-century: the text mentions that virgins during their wedding night fear wounds in their "other place," which Hallett interprets as referring to a fear of a wound acquired through vaginal intercourse.[120][126]

Despite the apparent omnipresence of this notion of a groom leading his wife, it is unclear if the groom physically led the bride during the ceremony: Roman literature provides few, if any, actual descriptions a groom genuinely leading the bride. Karen Hersch proposes that the "earliest forms of the Roman wedding" may have involved a literal leading of the bride that vanished from later versions of the Roman wedding ceremony, although the language describing the leading of the bride persisted. Hersch further theorizes that the absence of the groom could be partially explained by the potential origins of the Roman wedding in the rape of the Sabine Women, an event in Roman mythology in which Romulus kidnapped Sabine women and brought them to Rome as brides.[120] According to Hersch, the evocation of the myth of the Sabine women was intended to convey to the bride that she singlehandedly had the capacity to bring "concordia," meaning "union" or "harmony," to the Roman marriage by emulating the submissiveness and loyalty the Sabine brides demonstrated to their newfound Roman husbands.[4] Festus explicitly supports the interpretation of the domum deductio as a ritual originated from the Rape of the Sabine Women, declaring that the kidnapping was reenacted during the wedding ceremony as Romulus garnered great benefits from the rape of the Sabines.[4][118] Dionysius of Halicarnassus, a 1st-century BCE Greek rhetorician, records that, after the rape, Romulus attempted to alleviate the despair of the captured girls by informing them that it was a Greek custom and the most illustrious manner of marriage for women, before imploring them to thank Tyche (the Greek equivalent of the Roman goddess Fortuna) for allotting them husbands.[120][127]

The existence of ornaments decorating the groom's house in preparation for the arrival of the bride is strongly hinted at by the mention of their absence at the wedding of Cato and Marcia: Lucan claims that—at this wedding—no festal wreath crowned the gate, a gleaming infula was not entangled around the posts, ivory steps were not present, a wedding torch was not carried, the couch was not embroidered with gold, and the bride herself was not adorned with the wedding garland, the flammeum, a necklace ("monile"), or a jeweled girdle ("balteus") to confine her "flowing robe;" her arm was also not covered by a type of linen garment called a "supparum."[128] Hersch claims that such opulence and decor, in particular the parts related to the bride, likely conveyed her value as the manager of domestic affairs.[4] Claudian provides a separate account of wedding decoration in his description of the wedding of Honorius and Maria, mentioning that Venus declared that Concordia shall weave a garland, a Charis shall gather flowers for the banquet, and others shall entwine a doorpost with myrtle, spread the tapestries of Sidon, and unfold yellow-dyed silks. Furthermore, the wedding bed was said to have been furnished with the spoils of war garnered through campaigns against the various enemies of Rome and decorated with gemstones.[129][130]

According to Pliny the Elder, pig's fat was sacred to the "ancients" and, during his lifetime, continued to be smeared upon doorposts by brides when they were entering the house of the groom.[131] He also cites an author named Masurius, who claims that the "ancients" gave the "palm" to wolf fat and that, likewise, brides coated doorposts with wolf fat to safeguard themselves against any "evil medicine" ("mali medicamenti").[132] Servius similarly states that the fat and limbs of wolves were viewed as remedies for various medical ailments. Furthermore, Servius explains that this tradition derives from the myth of Romulus and Remus, the two legendary founders of Rome who were nursed by a she-wolf; he clarifies that these rituals were performed to ensure the bride knew that she was entering into a sacred household and because of the loyalty of the wolf, leading Karen Hersch to speculate that the tradition may have symbolized the faithfulness of the bride.[4][133] Servius also claims that was considered a baleful omen for the bride to trample over the threshold ("limen") of the house, because it was the "thing of Vesta" ("rem Vestae") and therefore sacred.[134] However, Ovid claims that the tradition is more associated with the god Janus, who exists as a character in Ovid's Fasti and declares that he guards the threshold.[135] This tradition is also seemingly referenced by Catullus, who commands a bride to cross the threshold (also called a "limen") with "a good omen" and her "golden feet."[7] In another one of Catullus's poems, he describes a lady standing upon this border with a worn-out shoe, potentially indicating—according to Karen Hersch—that this woman may have been of impure morality.[136] In the play Casina by Plautus, the maid Pardalisca instructs the bride—the slave Chalinus disguised as Casina—to lift her feet over the threshold, explaining that this ritual must occur for her to always remain more powerful than the groom, to conquer him, and to despoil him.[137] The historian Gordon Williams suggests that this speech was likely given by the mater familias Cleustrata and functioned as an intentional subversion of a legitimate Roman nuptial speech; therefore, he concludes that the inverse of these claims, the idea of a bride being subservient to their husband, must have been the genuine advice offered to the bride.[138] Karen Hersch adds that the proposition of Williams is unprovable, and that—even if true—the wedding depicted in Casina may more accurately reflect Greek wedding customs than Roman practices. The Roman author Plutarch proposes that the ritual carried almost the opposite significance: that the bride was involuntarily carried across the border by other individuals, symbolizing either that she was unwilling to enter the house where she would lose her virginity or that she was unwilling to enter abandon her family and therefore needed to be forcefully brought into the new home.[4][139]

According to various Roman sources, there was some mention of the names "Gaia" during the Roman wedding ceremony. Plutarch—the comprehensive source available on this matter—suggests that it occurred during the domum deductio, stating that when the bride was led to their new home, the phrase "Ubi tu Gaius, ego Gaia" ("Where you are Gaius, I am Gaia") was uttered. Hersch argues that Plutarch implies that the bride did not necessarily utter this phrase of her own volition, as he utilizes the verb "κελεύουσιν" ("keleúousin," "to urge, command") to describe the ritual. Furthermore, Hersch notes that the specific adverb utilized by Plutarch, "ὅπου" ("hópou," "where"), could be translated into a Latin either as "ubi" or "quando" (both of which could mean "when"), which Hersch suggests could convey significantly distinct meanings. Plutarch proposes two possible explanations for the ritual: one suggests that it may originated to suggest that the couple had equitable control over the household, and thus–in Plutarch's view—the phrase could be rendered as "Wherever you are lord and master, there I am lady and mistress." Alternatively, he indicates that the phrase derives from Gaia Caecilia, the name adopted by Tanaquil according to some Roman sources, who is herself inaccurately labeled by Plutarch as the wife of one of Tarquin the Elder's sons even though other Roman authors label her as the wife of Tarquin.[140] Festus also cites Tanaquil as the origin of this tradition, adding that Roman brides honored Tanaquil—whose spindle and distaff were alleged by Pliny to have been stored in the Temple of Sancus—because they sought a good omen for their wool-working skills.[141] According to Hersch, Plutarch further indicates that the names "Gaius" and "Gaia" may have functioned as placeholder names, equivalent to terms such as John or Jane Doe. Hersch suggests that the writings of the 1st-century CE rhetorician Quintilian carry a similar connotation, as they note that the names "Gaius" and "Gaia" were used at the wedding ceremony—in Hersch's view—"presumably to mean simply 'man and woman.'"[142] Another reference to the name "Gaia" being invoked at weddings appears in the works of Cicero, who mocks overly pedantic lawyers by remarking those who excessive attention to semantics might believe that the bride is literally renamed "Gaia" after the type of Roman marriage known as "coemptio."[4][143]

Legal status

[edit]This ritual has been interpreted as the defining moment of a Roman wedding, the moment in which the bride officially became a wife: Ulpian writes that the marriage has been complete when "ducta est uxor," meaning when the bride has been led, even if they have not entered the bedroom and lain with each other.[144][145] However, Ulpian notes other, apparently contradictory circumstances in which the bride was led, but the marriage is not valid as the bride due to the young age of the bride, which prevented them from legally marrying. In one scenario a bride under the age of 12 commits adultery ("adulterium") after having underwent the domum deductio; Ulpian argues that, since she was too young to be considered a "uxor" ("wife"), she could not be prosecuted for adultery as a married woman, but she could be prosecuted as a "sponsa" (meaning "bride" or "betrothed woman," interpreted by the scholar Lauren Caldwell as the latter in this instance). Ulpian writes that this legal reasoning is premised upon ideals outlined by the Emperor Septimius Severus (r. 193–211).[146] Caldwell argues that, although Ulpian concedes that the bride is not legally married, he implies that the ritual marks some variety of transition into adulthood or confirmation of engagement as he states that she is capable of choosing to commit the crime of "adulterium," which is described by the 2nd-century jurist Papinian as requiring extramarital sex with or by a married woman.[147][148]

In another anecdote, Ulpian describes a scenario in which the bride underwent the domum deductio despite being of the age of 12, thereby being too young to legally marry. According to Ulpian, the 2nd-century jurist Salvius Julianus argued that, in this specific instance, gift-giving between the spouses was invalid as the girl is a "sponsa" ("betrothed woman") not an "uxor." However, Ulpian reasons that the "sponsalia" ("betrothal") was the determining factor regarding whether the gifts were valid: they were legitimate had the betrothal occurred and illegitimate had the betrothal not occurred.[149] Caldwell interprets this description of a wedding with all the trappings of a standard Roman wedding ceremony but without accompanying legal validity, as evidence that, at least for the majority of the Roman populace, the wedding ceremony was not necessarily connected to Roman law governing legitimate marriages. Caldwell further proposes that the wedding ceremony may have served largely social, rather than legal, functions: the wedding may have served to publicly broadcast the marriage and thus functioned as a representation of the legal union, rather than its direct equivalent.[148]

There appear to be various instances in Roman literature in which a wedding is described as lacking the presence of the groom: Papinian states that the groom, if he had been absent from a wedding in which the bride was led, was not entitled to claim any interests if the bride did not take any expense from his assets.[145][150] Another account from the Digests, authored by the 2nd-century jurist Ulpian, mentions that another jurist, Cinna, recorded an incident in which an individual who married a woman whilst away and then perished while returning from dinner by the Tiber.[151][152] However, the scholar Zuzanna Benincasa notes that the legal reasoning of Cinna, which implicitly accepts the possibility that one may "accept an absent wife" ("qui absentem accepit uxorem"), contradicts a separate ruling from the 2nd or 3rd century Roman jurist Julius Paulus that "an absent woman is not able to wed" ("femina absens nubere non potest").[153] Various possible explanations have been proposed to resolve this discrepancy; one theory proposes that a scribe may have been mistakenly wrote the accusative form "absentem" instead of the nominative form "absens," thereby altering the meaning of the text from describing an absent groom to an absent bride. The scholar Carlo Castello, although he accepted the potential transcription error, posited that the groom may have been present for the wedding feast in the house of the bride, and perished while returning to his home. Italian scholar of Roman law Edoardo Volterra argued for a different interpretation of the original text, arguing that although the scenario assumed the absence of the bride, it possessed a sense of mutual "affectio mairtalis" ("marital affection") that was confirmed by the relatives and friends of the bride, which ensured the legitimacy of the wedding.[145] In the Digests of Justinian, the Roman jurist Pomponius states that, even if the groom is not present, the Roman marriage could still be valid if it is conducted through letters and the bride undergoes the domum deductio, because the home of the groom is the "abode of matrimony" ("domicilium matrimonii").[154] However, the domum deductio is seemingly absent from the wedding of Cato and Marcia as described in the Pharsalia of Lucan as well as the wedding of Pudentilla to Apuleius recounted in the autobiographical telling of Apuleius himself.[155][156]

Fire and Water