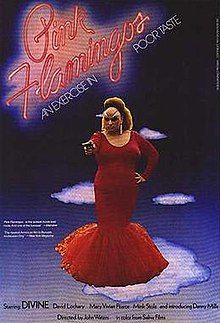

Pink Flamingos

| Pink Flamingos | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | John Waters |

| Written by | John Waters |

| Produced by | John Waters |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | John Waters |

| Edited by | John Waters |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | New Line Cinema |

Release date |

|

Running time | 92 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $12,000[1] |

| Box office | $1.9 million or $7 million[2] |

Pink Flamingos is a 1972 American black comedy film[a] by John Waters.[3] It is part of what Waters has labelled the "Trash Trilogy", which also includes Female Trouble (1974) and Desperate Living (1977).[3] The film stars the countercultural drag queen Divine as a criminal living under the name of Babs Johnson, who is proud to be "the filthiest person alive". While living in a trailer with her mother Edie (Edith Massey), son Crackers (Danny Mills), and companion Cotton (Mary Vivian Pearce), Divine is confronted by the Marbles (David Lochary and Mink Stole), a pair of criminals envious of her reputation who try to outdo her in filth. The characters engage in several grotesque, bizarre, and explicitly crude situations, and upon the film's re-release in 1997 it was rated NC-17 by the MPAA "for a wide range of perversions in explicit detail". It was filmed in the vicinity of Baltimore, Maryland, where Waters and most of the cast and crew grew up.

Displaying the tagline "An exercise in poor taste", Pink Flamingos is notorious for its "outrageousness", nudity, profanity, and "pursuit of frivolity, scatology, sensationology [sic] and skewed epistemology".[4] It features a "number of increasingly revolting scenes" that center on exhibitionism, voyeurism, sodomy, masturbation, gluttony, vomiting, rape, incest, murder, animal cruelty, cannibalism, zoophilia, castration, foot fetishism, and concludes, to the accompaniment of "How Much Is That Doggy in the Window?", with Divine's consumption of dog feces – "The real thing!" narrator Waters assures us. The film is considered a preliminary exponent of abject art.[5][6]

The film, at first semi-clandestine, has received a warm reception from film critics and, despite being banned in several countries, became a cult film in subsequent decades. In 2021, the film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[7]

Plot

[edit]Notorious criminal Divine lives under the pseudonym "Babs Johnson" with her mother Edie, delinquent son Crackers, and traveling companion Cotton. They share a trailer on the outskirts of Phoenix, Maryland, next to a gazing ball and a pair of plastic pink flamingos. After learning that Divine has been dubbed "the filthiest person alive" by a tabloid paper, jealous rivals Connie and Raymond Marble attempt to usurp her title.

The Marbles run a black market baby ring: they kidnap young women, have them impregnated by their manservant Channing, and sell the babies to lesbian couples. The proceeds are used to finance pornography shops and a network of dealers selling heroin in inner-city elementary schools. Raymond also earns money by exposing himself – with a large kielbasa sausage or turkey neck tied to his penis – to women and stealing their purses when they flee. Later in the film, one of Raymond's would-be targets, a trans woman, thwarts his scheme by exposing her breast, penis, and scrotum, causing Raymond to flee in shock.

The Marbles enlist a spy, Cookie, to gather information about Divine by dating Crackers. Cookie is raped by Crackers while crushing a live chicken between them as Cotton looks on through a window. Cookie then informs the Marbles about Babs' identity, her whereabouts, and her family – as well as her upcoming birthday party.

The Marbles send a box of human feces to Divine as a birthday present with a card addressing her as "Fatso" and proclaiming themselves "the filthiest people alive". Worried that her title has been seized, Divine declares that whoever sent the package must die. While the Marbles are gone, Channing dresses in Connie's clothes and imitates his employers' overheard conversations. When the Marbles return home, they are outraged to find Channing mocking them while wearing Connie's clothes, so they fire him and lock him in his "room" (a closet) while they head out to do evil deeds until they can return and throw him out for good after searching his stuff.

The Egg Man, who delivers eggs to Edie daily, confesses his love for her and proposes marriage, which she accepts. The Marbles arrive at the trailer to spy on Divine's birthday party. The birthday gifts include poppers, fake vomit, lice shampoo, a pig's head, and a meat cleaver. Entertainers feature a topless woman with a snake act and a contortionist who flexes his prolapsed anus in rhythm to the song "Surfin' Bird". Disgusted by the outrageous party, the Marbles anonymously contact the police, but Divine and her guests ambush the officers, hack up their bodies with the meat cleaver, and eat them. Afterwards, Edie and The Egg Man are wed, and he carts her off in a wheel barrow.

Divine and Crackers head to the Marbles' house, where they lick and rub the furniture, which excites them so much that Divine fellates Crackers. They find Channing and he begs to be released, but they are not sympathetic and force him to show them the two pregnant women held captive in the basement. Divine and Crackers free the women and hand them a large knife to deal with the tied-up Channing, stating they can kill him and Divine will do so herself if they aren't interested. The women then use the knife to emasculate Channing.

The Marbles burn Divine's beloved trailer to the ground; when they return home, their furniture – cursed by being licked by Divine and Crackers – "rejects" them, the cushions flying up and throwing them to the floor when they try to sit down. They also find that Channing has bled to death from his emasculation and the two women have escaped.

After finding the remains of their burned-out trailer, Divine, Crackers, and Cotton return to the Marbles' home, kidnap them at gunpoint, and bring them to the arson site. Divine calls the local tabloid media to witness the Marbles' trial and execution. Divine holds a kangaroo court and convicts the bound-and-gagged Marbles of "first-degree stupidity" and "assholism". Cotton and Crackers recommend a sentence of execution, so the Marbles are tied to a tree, coated in tar and feathers, and shot in the head by Divine.

Divine, Crackers, and Cotton enthusiastically decide to move to Boise, Idaho. Spotting a small dog defecating on the sidewalk, Divine scoops up the feces with her hand and puts them in her mouth – proving, as the voice-over narration by Waters states, that Divine is "not only the filthiest person in the world, but she is also the filthiest actress in the world".

Cast

[edit]- Divine as Divine/Babs Johnson

- David Lochary as Raymond Marble

- Mary Vivian Pearce as Cotton

- Mink Stole as Connie Marble

- Danny Mills as Crackers

- Edith Massey as Edie

- Channing Wilroy as Channing

- Cookie Mueller as Cookie

- Paul Swift as The Egg Man

- Susan Walsh as Suzie

- Linda Olgierson as Linda

- Pat Moran as Patty Hitler

- Steve Yeager as Nat Curzan

- George Figgs as bongo player

- David Gluck as The Singing Asshole

- Elizabeth Coffey as a transgender woman who shocks Raymond

- Vince Peranio as musician at party

- Van Smith as party guest

- Pat LeFaiver as Etta

- Jacqueline Zajdel (credited as Jackie Sidel) as Merle

- John Waters as Mr. J, the narrator (uncredited)

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]Divine's friend Bob Adams described the trailer set as a "hippie commune" in Phoenix, Maryland, and noted that their living quarters were in a farmhouse without hot water. Adams added that ultimately Divine and Van Smith decided to sleep at Susan Lowe's home in Baltimore, and that they would awake before dawn to apply Divine's makeup before being driven to the set by Jack Walsh. "Sometimes Divy would have to wait out in full drag for Jack to pull the car around from back, and cars full of these blue-collar types on their way to work would practically mount the pavement from gawking at him,"[8] Adams said.

Divine's mother, Frances, later said she was surprised that her son was able to endure the "pitiful conditions" of the set, noting his "expensive taste in clothes and furniture and food".[9]

John Waters told an interviewer "I was high when I wrote this movie. I was NOT high when I filmed it."

Filming

[edit]Principal photography began October 1, 1971 and ended January 12, 1972. Shot on a budget of only $12,000, Pink Flamingos is an example of Waters' style of low-budget filmmaking inspired by New York underground filmmakers like Kenneth Anger, Andy Warhol, and brothers Mike and George Kuchar.[4] Stylistically, it takes its cues from "exaggerated seaport ballroom drag-show pageantry and antics" with "classic '50s rock-and-roll kitsch classics".[4] Waters' idiosyncratic style – also characterized by its "homemade Technicolor" look, the result of high amounts of indoor paint and make-up – was dubbed the "Baltimore aesthetic" by art students at Providence.[4]

Post-production

[edit]Waters' rough editing added "random Joel-Peter Witkin-esque scratches and Stan Brakhage-moth-wing-like dust marks" to the film, apart from sound delays between shots.[4] Waters has stated that Armando Bo's 1969 Argentine film Fuego influenced not only Pink Flamingos, but his other films: "If you watch some of my films, you can see what a huge influence Fuego was. I forgot how much I stole. ... Look at Isabel's makeup and hairdo in Fuego. Dawn Davenport, Divine's character in Female Trouble, could be her exact twin, only heavier. Isabel, you inspired us all to a life of cheap exhibitionism, exaggerated sexual desires and a love for all that is trash-ridden in cinema."[10]

Music

[edit]The film uses a number of mainly single B-sides and a few hits of the late 1950s/early 1960s, sourced from Waters' record collection, and without obtaining rights. After rights were obtained, a soundtrack CD coincided with the 25th anniversary release of the film on DVD in 1997.[11]

- "The Swag" – Link Wray and His Ray Men

- "Intoxica" – The Centurians

- "Jim Dandy" – LaVern Baker

- "I'm Not a Juvenile Delinquent" – Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers

- "The Girl Can't Help It" – Little Richard

- "Ooh! Look-a-There, Ain't She Pretty?" – Bill Haley & His Comets

- "Chicken Grabber" – The Nighthawks

- "Happy, Happy Birthday Baby" – The Tune Weavers

- "Pink Champagne" – The Tyrones

- "Surfin' Bird" – The Trashmen

- "Riot in Cell Block #9" – The Robins

- "(How Much is) That Doggie in the Window" – Patti Page

The song "Happy, Happy Birthday, Baby" is used as a replacement for "Sixteen Candles", by The Crests, which appeared in the original release and for which permission could not be obtained.

Release

[edit]Pink Flamingos had its world premiere on March 17, 1972, at a screening sponsored by the Baltimore Film Festival. The event was held on the campus of the University of Baltimore, where it sold out for three successive shows. The film had aroused particular interest among fans of underground cinema following the success of Multiple Maniacs, which had begun to be screened in cities such as New York, Philadelphia, and San Francisco.[12]

Being picked up by the then-small independent company New Line Cinema, Pink Flamingos was later distributed to Ben Barenholtz, the owner of the Elgin Theater in New York City. At the Elgin, Barenholtz had been promoting the midnight movie scene, primarily by screening Alejandro Jodorowsky's acid western film El Topo (1970), which had become a "very significant success" in "micro-independent terms". Barenholtz felt that being of an avant-garde nature, Pink Flamingos would fit in well with this crowd, subsequently screening it at midnight on Friday and Saturday nights.[13] The original trailer used by New Line Cinema did not feature any footage from the actual film, and instead consisted almost entirely of interviews with filmgoers who had just seen the film.[14] This trailer was included in the 25th anniversary re-release.

The film soon gained a cult following of filmgoers who came to the Elgin Theatre for repeat viewings, a group Barenholtz characterized as initially composed primarily of "downtown gay people, more of the hipper set", but after a while, Barenholtz noted that this group eventually broadened as the film also became popular with "working-class kids from New Jersey who would become a little rowdy". Many of these cult cinema fans learned all of the lines in the film, and recited them at the screenings, a phenomenon which later became associated with another popular midnight movie of the era, The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975).[15]

Ban

[edit]The film was initially banned in Switzerland and Australia, as well as in some provinces in Canada and Norway.[16] It was eventually released uncut on VHS in Australia in 1984 with an X rating, but distribution of the video has since been discontinued. The 1997 version was cut by the distributor to achieve an R18+ after it was also refused classification. No submissions of the film have been made since, but it has been said that one of the reasons for which it was banned (as a film showing actual sexual activity cannot be rated X in Australia if it also features violence, so the highest a film such as Pink Flamingos could be rated is R18+) would now not apply, given that the depiction of actual sex was passed within the R18+ rating for Romance in 1999, two years following Pink Flamingos' re-release.[17] The film was originally rated as R18 by the Classification Office in New Zealand with no cuts, but was later refused classification on a re-submission in 2024, effectively banning the film.[18]

Home media

[edit]Pink Flamingos was released on VHS and Betamax in 1981, and the re-release in 1997 from New Line Home Video became the second best-selling VHS for its week of release. The film was released in the John Waters Collection DVD box set along with the original NC-17 version of A Dirty Shame, Desperate Living, Female Trouble, Hairspray, Pecker, and Polyester. The film was also released in a 2004 special edition with audio commentaries and deleted scenes as introduced by Waters in the 25th anniversary re-release (see below). The film was released on Blu-ray on June 28, 2022, by the Criterion Collection, featuring a new 4K restoration.[19]

Alternative versions

[edit]- The 25th anniversary re-release version contains a re-recorded music soundtrack, re-mixed for stereo, plus 15 minutes of deleted scenes following the film,[20] introduced by Waters. Certain musical excerpts used in the original version, including Igor Stravinsky's The Rite of Spring, had to be removed and replaced in the re-release, since the music rights had never been cleared for the original release.[11]

- Because of this film's explicit nature, it has been edited for content on many occasions throughout the world. In 1973, the U.S. screened version edited out most of the fellatio scene, which was later restored on the 25th anniversary DVD. Canadian censors recently restored five of the seven scenes that were originally edited in that country. Hicksville in Long Island, New York, banned the film altogether.[16] The Japanese laserdisc version contains a blur superimposed over all displays of pubic hair. Prints also exist that were censored by the Maryland Censor Board.

- The first UK video release of Pink Flamingos in November 1981 (prior to BBFC video regulation requirements) was completely uncut. It was issued by Palace as part of a package of Waters films they had acquired from New Line Cinema. The package included Mondo Trasho (double-billed with Sex Madness), Multiple Maniacs (double-billed with Cocaine Fiends), Desperate Living, and Female Trouble. The 1990 video re-release of Pink Flamingos (which required BBFC approval) was cut by three minutes and four seconds (3:04), the 1997 issue lost two minutes and forty-two seconds (2:42), and the pre-edited 1999 print by two minutes and eight seconds (2:08).

- The 2009 Sydney Underground Film Festival screened the film in Odorama for the first time, using scratch 'n' sniff cards similar to the ones used in Waters' later work Polyester.

- John Waters recast the film with children and rewrote the script to make it kid-friendly in a 2014 project, Kiddie Flamingos. The 74-minute video features children wearing wigs and costumes modeled on the originals and performing roles originated by Divine, Mink Stole, Edith Massey, and others. Waters has said the new version, filmed in one day with actors drawn mostly from friends' children, is in some ways more perverse than the original. The film was shown on a continuous loop in the Black Box gallery at the Baltimore Museum of Art from September 2016 through January 2017.[21]

Reception

[edit]On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 84% based on 50 reviews, with an average rating of 7.3/10. The website's critics consensus reads, "Uproarious and appalling, Pink Flamingos is transgressive camp that proves as entertaining as it does shocking."[22] Metacritic, which uses a weighted average, assigned the film a score of 47 out of 100, based on 10 critics, indicating "mixed or average" reviews.[23] In the "Cult Movies" episode of the UK documentary series Mark Kermode's Secrets of Cinema, Kermode admitted that Pink Flamingos is "one of the very few films that I have ever walked out of, when I first saw it as a teenager on a late-night double bill at the Phoenix in East Finchley".[24] Roger Ebert gave it zero stars when he reviewed it in 1997 for the 25-year anniversary (he and Gene Siskel did not review the film on their TV show) but clarified that he gave the film no stars because he felt "stars don't seem to apply" to Pink Flamingos, which he saw as more of an object and a curiosity than a movie.

Like the underground films from which Waters drew inspiration, which provided a source of community for pre-Stonewall queer people, the film has been widely celebrated by the LGBT community[25] and has been described as "early gay agitprop filmmaking".[4] This, coupled with its unanimous popularity among queer theorists, has led to the film being considered "the most important queer film of all time".[26] Pink Flamingos is also considered an important precursor of punk culture.[27]

Despite Waters having released similar films, such as Mondo Trasho and Multiple Maniacs, it was Pink Flamingos that drew international attention.[4] Like other underground films, it fed the rising popularity of midnight movie screenings, at which it generated a dedicated cult following that carried the film for a 95-week run in New York City and ten consecutive years in Los Angeles.[4][28] For its 25th anniversary, the film was re-released in 1997, featuring a post-film commentary by Waters in which he introduced and discussed deleted scenes,[4] adding fifteen minutes of material.[20] American "New Queer Cinema" director Gus Van Sant has described the film as "an absolute classic piece of American cinema, right up there with The Birth of a Nation, Dr. Strangelove, and Boom!"[4] The Library of Congress inducted Pink Flamingos to the National Film Registry in December 2021.[29]

Influence

[edit]Divine

[edit]The final scene in the film would prove particularly infamous, involving the character of Babs eating fresh dog feces; as Divine later told a reporter, "I followed that dog around for three hours just zooming in on its asshole" waiting for it to empty its bowels so that they could film the scene. In an interview not in character, Harris Milstead revealed that he soon called an emergency room nurse, pretending that his child had eaten dog feces, to inquire about possible harmful effects (there were none).[30] The scene became one of the most notable moments of Divine's acting career, and he later complained of people thinking that "I run around doing it all the time. I've received boxes of dog shit – plastic dog shit. I have gone to parties where people just sit around and talk about dog shit because they think it's what I want to talk about". In reality, he remarked, he was not a coprophile but only ate excrement that one time because "it was in the script".[31]

Divine asked his mother, Frances Milstead, not to watch the film, a wish that she obliged. Several years before his death, Frances asked him if he had really eaten dog excrement in the film, to which he "just looked at me with that twinkle in his blue eyes, laughed, and said 'Mom, you wouldn't believe what they can do nowadays with trick photography.'"[9]

Cultural influence

[edit]The film has a reputation as a midnight movie classic cult with audience participation similar to The Rocky Horror Picture Show.

- The Funday PawPet Show holds what is called the "Pink Flamingo Challenge", in which the ending to the film is played to the audience while they eat a (preferably chocolate) confection. Videos of the show are forbidden from showing the clip, only the reaction of the audience.[citation needed]

- Theater patrons often received free "Pink Phlegmingo" vomit bags.[citation needed]

Death metal band Skinless sampled portions of the Filth Politics speech for the songs "Merrie Melody" and "Pool of Stool", both on their second album, Foreshadowing Our Demise.[citation needed]

Joe Jeffreys, a drag historian, mentioned seeing in Pink Flamingos a poster for the documentary film The Queen (1968), featuring Flawless Sabrina, and stated that it influenced his career path to document the history of drag with the Drag Show Video Verite.[32]

Cancelled sequel

[edit]Waters had plans for a sequel, titled Flamingos Forever. Troma Entertainment offered to finance the picture, but it was never made, as Divine refused to be involved, and Edith Massey died in 1984.[16]

After reading the script, Divine had refused to be involved as he believed that it would not be a suitable career move, for he had begun to focus on more serious, male roles in films like Trouble in Mind. According to his manager, Bernard Jay, "What was, in the early seventies, a mind-blowing exercise in Poor Taste, was now, we both believed, sheer Bad Taste. Divi[ne] felt the public would never accept such an infantile effort in shock tactics some fifteen years later and by people fast approaching middle age."[33]

The script for Flamingos Forever would later be published in John Waters' 1988 book Trash Trio, which also included the scripts for Pink Flamingos and Desperate Living.

See also

[edit]- List of American films of 1972

- List of banned films

- List of cult films

- Divine Trash

- In Bad Taste

- Cinema of Transgression

Notes

[edit]- ^ Pink Flamingos has been variously categorized as a comedy, camp, or postmodern exploitation film

References

[edit]- ^ "How John Waters and Mink Stole made notorious cult film Pink Flamingos". TheGuardian.com. March 17, 2020.

- ^ Donahue, Suzanne Mary (1987). American film distribution : the changing marketplace. UMI Research Press. p. 296. ISBN 9780835717762. Please note figures are for rentals in US and Canada

- ^ a b Levy, Emanuel (July 14, 2015). Gay Directors, Gay Films?. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0231152778.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Van Sant, Gus (April 15, 1997). "Timeless trash". The Advocate. No. 731. Here Publishing. pp. 40–41. ISSN 0001-8996. Retrieved March 10, 2016.

- ^ Kutzbach, Konstanze; Mueller, Monika (July 27, 2007). The Abject of Desire: The Aestheticization of the Unaesthetic in Contemporary Literature and Culture. Rodopi. ISBN 978-9042022645.

- ^ What Culture#16 Archived July 20, 2018, at the Wayback Machine; Pink Flamingos

- ^ Tartaglione, Nancy (December 14, 2021). "National Film Registry Adds Return Of The Jedi, Fellowship Of The Ring, Strangers On A Train, Sounder, WALL-E & More". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved December 14, 2021.

- ^ Milstead, Heffernan and Yeager 2001. pp. 61–62.

- ^ a b Milstead, Heffernan and Yeager 2001. p. 61.

- ^ Corliss, Richard (August 7, 2010). "Isabel Sarli: A Sex Bomb at Lincoln Center". Time. Archived from the original on August 26, 2010. Retrieved April 13, 2011.

- ^ a b "Various – John Waters' Pink Flamingos Special 25th Anniversary Edition Original Soundtrack". discogs.com. April 22, 1997. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- ^ Milstead, Heffernan and Yeager 2001. pp. 66–67.

- ^ Milstead, Heffernan and Yeager 2001. pp. 69-70.

- ^ Pink Flamingos - Theatrical Trailer. New Line Cinema.

- ^ Milstead, Heffernan and Yeager 2001. pp. 70–71.

- ^ a b c Harrington, Richard (April 6, 1997). "Revenge of the Gross-Out King! John Waters's 'Pink Flamingos' Enjoys a 25th-Year Revival". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- ^ Films: P. Refused-Classification.com. Retrieved October 25, 2011.

- ^ Retrieved June 11, 2024

- ^ Criterion Announces June Releases, retrieved June 16, 2022

- ^ a b "Pink Flamingos (18) (CUT)". British Board of Film Classification. June 27, 2013. Retrieved June 29, 2013.

- ^ "2016 Kiddie Flamingos Details". Baltimore Museum of Art. Archived from the original on October 11, 2016. Retrieved October 10, 2016.

- ^ "Pink Flamingos". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved April 8, 2024.

- ^ "Pink Flamingos". Metacritic. Retrieved January 22, 2020.

- ^ "Cult Movies". Mark Kermode's Secrets Of Cinema. Season 3. Episode 3. January 25, 2021. BBC. BBC Four.

- ^ Benshoff, Harry M. (June 17, 2004). Queer Cinema: The Film Reader. Routledge. p. 9. ISBN 978-0415319874. Retrieved March 10, 2016.

- ^ Oyarzun, Hector (January 3, 2016). "20 Essential Films For An Introduction To Queer Cinema". Taste of Cinema. Retrieved March 10, 2016.

- ^ Gleiberman, Owen (April 18, 1997). "Pink Flamingos". Entertainment Weekly. Time Inc. Retrieved March 11, 2016.

- ^ Mathijs, Ernest; Sexton, Jamie (March 30, 2012). Cult Cinema. John Wiley & Sons. p. 136. ISBN 978-1405173735.

- ^ Ulaby, Neda (December 14, 2021). "'Return of the Jedi,' 'Selena' and 'Sounder' added to National Film Registry". NPR.

- ^ Divine Waters, 1985

- ^ Milstead, Heffernan and Yeager 2001. p. 65.

- ^ Ryan, Hugh (March 7, 2015). "Queen Sabrina, Flawless Mother". Vice. Retrieved May 2, 2017.

- ^ Jay 1993. p. 211.

Bibliography

[edit]- Jay, Bernard (1993). Not Simply Divine!. London: Virgin Books. ISBN 0-86369-740-2.

- Milstead, Frances; Heffernan, Kevin; Yeager, Steve (2001). My Son Divine. Los Angeles and New York: Alyson Books. ISBN 978-1-55583-594-1.

External links

[edit]- Pink Flamingos at IMDb

- Pink Flamingos at Rotten Tomatoes

- Pink Flamingos at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- Pink Flamingos at the TCM Movie Database

- Pink Flamingos: The Battle of Filth – an essay by Howard Hampton at The Criterion Collection

- Pink Flamingos at the Dreamland website

- 1972 films

- 1972 black comedy films

- 1972 crime films

- 1972 independent films

- 1972 LGBTQ-related films

- 1970s American films

- 1970s crime comedy films

- 1970s English-language films

- 1970s exploitation films

- American black comedy films

- American crime comedy films

- American exploitation films

- American independent films

- American LGBTQ-related films

- Animal cruelty incidents in film

- Bisexuality-related films

- Censored films

- Drag (entertainment)-related films

- Films about cannibalism

- Films about dysfunctional families

- Films about incest

- Films about rape in the United States

- Films directed by John Waters

- Films produced by John Waters

- Films set in Baltimore

- Films shot in Baltimore

- Films with screenplays by John Waters

- Lesbian-related films

- LGBTQ-related black comedy films

- LGBTQ-related controversies in film

- Obscenity controversies in film

- United States National Film Registry films

- LGBTQ-related crime comedy films

- American films about revenge

- Cross-dressing in American films

- Films set in Idaho

- English-language black comedy films

- English-language independent films

- English-language crime comedy films

- Film controversies