Belgorod

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2018) |

Belgorod

Белгород | |

|---|---|

View of the city | |

|

| |

| Coordinates: 50°36′N 36°36′E / 50.600°N 36.600°E | |

| Country | Russia |

| Federal subject | Belgorod Oblast[1] |

| Founded | 1596[2] |

| Government | |

| • Body | Council of Deputies[3] |

| • Mayor[5] | Valentin Demidov[4] (UR) |

| Elevation | 130 m (430 ft) |

| Population | |

• Total | 356,402 |

• Estimate (January 2015)[7] | 384,425 |

| • Rank | 49th in 2010 |

| • Subordinated to | city of oblast significance of Belgorod[1] |

| • Capital of | Belgorod Oblast,[1] city of oblast significance of Belgorod[1] |

| • Urban okrug | Belgorod Urban Okrug[8] |

| • Capital of | Belgorod Urban Okrug[8] |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (MSK |

| Postal code(s)[10] | 308000–308002, 308004–308007, 308009–308020, 308023–308027, 308029, 308031–308034, 308036, 308099, 308700, 308880, 308890, 308899, 308940, 308960, 308961, 308967, 308971–308974, 308991–308994 |

| Dialing code(s) | +7 472[11] |

| OKTMO ID | 14701000001 |

| City Day | 5 August[12] |

| Website | www |

| |

Belgorod (Russian: Белгород, pronounced [ˈbʲelɡərət]; Ukrainian: Бєлгород)[a][13] is a city that serves as the administrative center of Belgorod Oblast, Russia, located on the Seversky Donets River, approximately 40 kilometers (25 mi) north of the border with Ukraine. It has a population of 339,978 (2021 Census).[14]

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1897 | 27,000 | — |

| 1926 | 31,000 | +14.8% |

| 1939 | 34,359 | +10.8% |

| 1959 | 72,278 | +110.4% |

| 1970 | 151,336 | +109.4% |

| 1979 | 239,814 | +58.5% |

| 1989 | 300,408 | +25.3% |

| 2002 | 337,030 | +12.2% |

| 2010 | 356,402 | +5.7% |

| 2021 | 339,978 | −4.6% |

| Source: Census data | ||

Etymology

The name Belgorod (Белгород) in Russian literally means "white city", a compound of "белый" (bely, "white, light") and "город" (gorod, "town, city"). The name is a reference to the region's historical abundance of limestone.[15]

Demographics

The population of Belgorod is 339,978 as of the most recent censuses: 339,978 (2021 Census);[14] 356,402 (2010 Census);[6] 337,030 (2002 Census);[16] 300,408 (1989 Soviet census).[17]

As of the 2021 Census, the ethnic composition of Belgorod was:

| Ethnicity | 2010[18] | 2021[19] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number1 | % | |

| Russians | 312,104 | 94.1% | 174,787 | 92.0% |

| Ukrainians | 11,120 | 3.4% | 4,109 | 2.2% |

| Others | 8,386 | 2.5% | 11,151 | 5.8% |

1149,931 people (or 44.1% of the population) residing in Belgorod did not state their ethnicity in the 2021 census.

Geography

Urban layout

This section contains a list of miscellaneous information. (September 2022) |

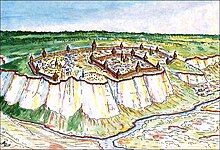

Like many Russian cities, Belgorod began as a fortified settlement. The oldest Belgorod fortress was built at the end of the 16th century on a chalk mountain. According to scientific excavations and surviving archival data, the first fortress outpost was erected in 1596.[20] The site of the construction of the defensive facility was the top of the Belaya Gora ("White Mountain"). This is the highest point of the right bank of the Seversky Donets channel. On 17 September 1650, voivode Vasily Petrovich Golovin laid the foundation for the third Belgorod Fortress on the left bank of the Vezenitsa River, which flows into the Seversky Donets.[21] In the fall of 1650, a wooden fort with 11 towers was attached to the rampart of the Belgorod line, which runs from the fortress town Bolkhovets to the mouth of the Vezelka River in the area of the former brewery. The two parts of the city were connected by the Nikolskaya Passage Tower located in the eastern wall of the Kremlin. The position of the eastern wall of the Kremlin corresponded to the modern street of the 50th anniversary of the Belgorod Oblast. With the expansion of the borders of the Russian state, the military significance of the Belgorod fortress gradually decreased and by the middle of the 18th century, only the Kremlin remained from the formidable fortress.[22]

In the fall of 1766, the new governor, Andrei Fliverk pushed for a new city plan. A regular street plan was developed and signed on 18 April 1767. The architect's signature is not legible, but it may have been signed by Andrey Kvasov. The central part of the plan was occupied by an octahedral "marketplace" with 64 stone shops and 20 warehouse barns. Moskovskaya, Kievskaya, Voronezhskaya and Kharkovskaya streets ran from the trading area in four directions. According to the plan, it was supposed to divide the entire city into 16 quarters, 4 of which should be built up with stone houses, and the rest with wooden and huts. The plan was executed formally without taking into account the buildings that survived the fire, the Kremlin fortress and the terrain.[23] On 28 April 1768, a new plan was developed[24] under the leadership of Andrey Kvasov who was the author of a number of city plans. The plans overlaid the old city center layout and the projected one. It provided for a trading area, which in the west adjoined the fortress Kremlin, and in the east ended with stone benches of the Gostiny dvor in the form of two arcs. The central planning axis was also chosen relative to which the directions of mutually perpendicular streets were formed.[citation needed]

Travel notes which were published in 1781 showed the location of a sketch of the ramparts of the lost ancient settlement. Only in the middle of the 1950s, the archaeologist Arkady Nikitin carried out excavations at the site of the first fortress, where the remains of ancient ramparts and ditches were still clearly visible.[25] though the fortress itself was destroyed already in the 1860s during the construction of the railway the eastern part of the chalk mountain, on which the Kremlin was located, was collapsed. The location of the first fortress approximately corresponded to the location of the modern car market on Byelaya Gora.[26][27]

In the 1780s, during the general survey of the Russian lands, several plans of Belgorod were fulfilled. When drawing up plans, an overlay of the old and new layouts of Kvasov was used. The plans described above give a distorted position of church estates, which were fixed when the city was laid and, as a rule, did not change. The plan, signed by the titular adviser Salkov, is the most accurate plan of Belgorod in the second half of the 18th century.[28]

Climate

Belgorod's climate is humid continental (Köppen climate classification Dfb slightly cooler than Dfa) featuring moderate precipitation. Winters are rather cold and changeable with frequent warmings followed by rains. Temperatures may occasionally fall below −15 °C (5 °F) for about one week or more. Summer is warm and either humid and rainy or hot and droughty. Autumn is mild and rainy. The Belgorod reservoirs get covered with ice by the end of November or the beginning of December, and the ice layer typically lasts until March or April.

- average year temperature: + 7.7 °C

- average humidity: 76%

- average wind speed: 5–7 m/s

- average precipitation 380–620 mm (14.96–24.41 in), mostly in summer.

| Climate data for Belgorod | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 6.6 (43.9) |

12.3 (54.1) |

19.4 (66.9) |

25.6 (78.1) |

34.4 (93.9) |

35.7 (96.3) |

38.9 (102.0) |

36.3 (97.3) |

33.5 (92.3) |

27.6 (81.7) |

17.4 (63.3) |

8.9 (48.0) |

38.9 (102.0) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | −3.0 (26.6) |

−2.9 (26.8) |

2.8 (37.0) |

13.2 (55.8) |

20.5 (68.9) |

23.9 (75.0) |

26.0 (78.8) |

25.2 (77.4) |

18.6 (65.5) |

11.1 (52.0) |

1.9 (35.4) |

−2.6 (27.3) |

11.3 (52.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −6.1 (21.0) |

−6.1 (21.0) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

8.9 (48.0) |

15.5 (59.9) |

19.4 (66.9) |

21.8 (71.2) |

21.2 (70.2) |

15.1 (59.2) |

8.0 (46.4) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

−5.6 (21.9) |

7.7 (45.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −10.0 (14.0) |

−9.9 (14.2) |

−4.0 (24.8) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

9.7 (49.5) |

14.1 (57.4) |

16.8 (62.2) |

16.3 (61.3) |

10.9 (51.6) |

4.7 (40.5) |

−2.8 (27.0) |

−9 (16) |

3.5 (38.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −34.5 (−30.1) |

−29.7 (−21.5) |

−31.1 (−24.0) |

−9.7 (14.5) |

−3.1 (26.4) |

2.9 (37.2) |

8.7 (47.7) |

7.1 (44.8) |

−2.5 (27.5) |

−6.2 (20.8) |

−21 (−6) |

−32.1 (−25.8) |

−34.5 (−30.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 52 (2.0) |

40 (1.6) |

36 (1.4) |

46 (1.8) |

48 (1.9) |

67 (2.6) |

72 (2.8) |

53 (2.1) |

49 (1.9) |

40 (1.6) |

52 (2.0) |

50 (2.0) |

605 (23.8) |

| Average precipitation days | 10 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 10 | 11 | 100 |

| Source 1: belgorod-meteo.ru [29] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: world-climates.com [30] | |||||||||||||

History

This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2022) |

Before the 20th century

There was a settlement of the Slavic tribe of Severians in the area, which was probably destroyed at the beginning of the 10th century by the nomadic Pechenegs. In 965, the lands in the upper reaches of Seversky Donets were annexed to the Principality of Pereyaslavl.

Records first mention the settlement in 1237, when the Mongol-led army of Batu Khan ravaged it during the Mongol invasion of Kievan Rus'. It is unclear whether this Belgorod stood on the same site as the current city. In 1596 Tsar Feodor Ioannovich of Russia ordered its re-establishment as one of numerous forts set up to defend Russian southern borders from the Crimean Tatars.[2] Belgorod was part of a chain of fortification lines, created by Grand Duchy of Moscow and later the Tsardom of Russia to protect it from the Crimean–Nogai slave raids that ravaged the southern provinces of the country during the Russo-Crimean Wars.[31] The tsar appointed two princes-governors to supervise the construction of Belgorod: Mikhail Vasilyevich Nozdrovaty and Andrei Romanovich Volkonsky. The first Belgorod fortress was built on the high right bank of the Seversky Donets, in the area of the current car market; the Belgorod Kremlin was close to the present-day Belaya Gora restaurant. The legendary White Mountain has not survived, as it was completely torn down for chalk mining in the 1950s.

The first Belgorod fortress stood for sixteen years, withstanding several major attacks, both from the Tatars and from the Polish–Lithuanian troops who participated in the wars with the Russian state during the Time of Troubles. In 1612 the Belgorod fortress was taken and burned by a detachment of Lithuanians. The governor, Nikita Likharev, by order of the tsar, was already building the second Belgorod fortress on the opposite bank of the Seversky Donets the following year, 1613. Over the next decades, Belgorodians repulsed a large number of attacks on their lands. By the middle of the 17th century, the question arose about the construction of a new Belgorod fortress three kilometers south of the existing one.

In the 17th century Belgorod suffered repeatedly from Tatar incursions, against which Russia built (from 1633 to 1740) an earthen wall, with twelve forts, extending upwards of 200 miles (320 kilometres) from the Vorskla in the west to the Don in the east, and called the Belgorod line. In 1666 the Moscow Patriarchate established an archiepiscopal see in the town.[32]

Tsar Peter the Great visited Belgorod on the eve of the Battle of Poltava in 1709.

After the Russian border moved south following successful wars against the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in the second half of the 17th century, the strategic importance of the city gradually decreased, and on 13 May 1785, by decree of Catherine II, Belgorod was excluded from the number of fortresses of the Russian Empire. From that moment on, the city plunged into the measured provincial life of the central black earth zone of Russia. Military life was replaced by agricultural life, the number of spiritual, educational, industrial and commercial institutions were growing, and in the historical chronicles of the Russian Empire, the city seems to have fallen asleep for a century. The Belgorod province disappeared from the geographical maps, and the city was for a long time a part of the first Kursk Governorate, then the Kursk province, and, finally, the Kursk region. A dragoon regiment had its base in the town until 1917.

Ioasaph of Belgorod, an 18th-century bishop of Belgorod and Oboyanska, became widely venerated as a miracle worker and was glorified as a saint of the Russian Orthodox Church in 1911.

20th and 21st centuries

Soviet power was established in the city on 26 October (8 November) 1917. On 10 April 1918, troops of the Imperial German Army occupied Belgorod. After the conclusion of the Brest-Litovsk peace treaty of 9 February 1918 the demarcation line passed to the north of the city. Belgorod became part of the newly proclaimed Ukrainian People's Republic (February to May 1918) and Ukrainian State headed by Hetman Pavlo Skoropadskyi.

On 20 December 1918, after the overthrow of German-backed Skoropadskyi, the Soviet Red Army regained control over the city, which became part of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic. From 24 December 1918 to 7 January 1919, the Provisional Workers' and Peasants' Government of Ukraine, then led by General Georgy Pyatakov, was based in Belgorod. The city served as the temporary capital of the Ukrainian People's Republic. From 23 June to 7 December 1919, the Volunteer Army occupied the town as part of White-controlled South Russia.

From September 1925, the territorial 163rd Infantry Regiment of the 55th Infantry Division of Kursk was stationed in Belgorod. In September 1939, it was deployed to the 185th Infantry Division.

On 2 March 1935, the Presidium of the Central Executive Committee of the Soviet Union decided to allocate the city of Belgorod, Kursk region, into an independent administrative unit directly subordinate to the Kursk Regional Executive Committee.

The German Wehrmacht occupied Belgorod from 25 October 1941 to 9 February 1943. The Germans operated a forced labour battalion for Jews in the city.[33] The Germans re-captured it on 18 March 1943 in the final move of the Third Battle of Kharkov. On 12 July 1943, during the Battle of Kursk, the largest tank battle in world history took place near Prokhorovka, and the Red Army definitively retook the city on 5/6 August 1943. The Belgorod Diorama is one of the World War II monuments commemorating the event.

In 1954, the city became the administrative center of Belgorod Oblast and rapidly developed as a regional industrial and cultural center.[34] The major educational centers of the city are Belgorod State University, the Belgorod Technological University, the Belgorod Agrarian University, and the Financial Academy. Belgorod Drama Theater is named after the famous 19th-century actor Mikhail Shchepkin, who was born in this region.

On 22 April 2013, a mass shooting occurred at approximately 2:20 PM Moscow time on a street in Belgorod. The shooter, identified as 31-year-old Sergey Pomazun (Russian: Сергей Помазун), opened fire with a semi-automatic rifle on several people at a gun store and on a sidewalk, killing all six people whom he hit: three people at the store and three passers-by, including two teenage girls. Pomazun was apprehended after an extensive day-long manhunt; during his arrest, he wounded a policeman with a knife. He was sentenced to life in prison on 23 August 2013.

There were several attacks on Belgorod during the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Russian officials claimed that Belgorod was repeatedly targeted by indiscriminate Ukrainian attacks.[35] On 1 April 2022, two Ukrainian Mi-24 performed a night raid and set fire to a fuel depot in Belgorod, in a low-altitude airstrike.[36][37] On 20 April 2023, a Russian Su-34 fighter jet accidentally dropped a bomb on the city, leaving a crater 20 metres (66 ft) across and injuring two people.[38][39] On 22 April, more than 3,000 people were evacuated from their homes after an undetonated explosive was found; it was not known if the second bomb had come from the same aircraft.[40] On 30 December, a Ukrainian airstrike killed 25 people and wounded over 100.[41] In March 2024, authorities began evacuating 9,000 children from the city and wider region due to shelling and drone attacks.[42] On 6 May, at least six people were killed following a Ukrainian drone strike.[43] On 12 May, 16 people were killed when a section of an apartment block collapsed. Russian MOD claimed it as a Ukrainian missile strike.[44] CIT investigators said the building was most likely hit by a Russian bomb, as the explosion occurred on the North-Eastern side of the building, opposite to the border with Ukraine.[45][46]

Administrative and municipal status

Belgorod is the administrative center of the oblast.[1] Within the framework of administrative divisions, it is incorporated as the city of oblast significance of Belgorod—an administrative unit with status equal to that of the districts.[1] As a municipal division, the city of oblast significance of Belgorod is incorporated as Belgorod Urban Okrug.[8]

For administrative purposes, Belgorod is divided into two city okrugs:

- Vostochny ("Eastern"), population: 141,844 (2010 Census)[6]

- Zapadny ("Western"), population: 214,558 (2010 Census)[6]

Transportation

There has been a railway connection between Belgorod and Moscow since 1869.[47] The city is served by Belgorod International Airport (EGO) in the north of the city.

There are two bus stations: Bus Belgorod, Belgorod- 2 Bus Terminal (located on the forecourt), and the bus stop complex Energomash. The Energomash bus station is mainly for commuter buses. Buses run from the Belgorod-2 station mainly to nearby regional centers, and depart in accordance with the arrival of trains.

Trolleybus services were discontinued on 30 June 2022 and replaced by diesel buses, despite public support for retention of the trolleybus system. The officially cited reason for the closure was inadequate condition of the overhead contact lines and insufficient funds for its modernization. The length of trolley lines was over 120 km (75 mi). Trolleybus city park consisted of 150 pieces of equipment, mainly Russian-made trolley ZiU-682V, 2 units ZiU-683, operated from 1990, and 3 units ZiU-6205, 30 units "Optima", and one trolley Skoda-VSW -14Tr, which started operation in 1996. The city administration purchased 15 new ZiU-682G trolleybuses in 2002, another 20 new ZiU-682Gs in 2005, 30 Trolza-5275.05 "Optima" trolleybuses in 2011, and 20 new ACSM-420 trolleybuses in 2013.[citation needed]

Culture and art

Theaters

- Belgorod Drama Theater

- Belgorod Puppet Theater

- Two monkeys, Belgorod clowning theater

Museums

- Belgorod historical museum

- Belgorod Art Museum

- Belgorod Museum of Folk Culture

- Belgorod Diorama of the Tank Battle of 1943

Festivals

- White mask, a festival of street arts

Notable people

- Ioasaph of Belgorod, 18th century bishop

- Viktoria Brezhneva, wife of Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev

- Svetlana Khorkina, Olympic gymnast

- Natalia Zuyeva, Olympic rhythmic gymnast

- Alexey Shved, basketball player

- Vadim Nemkov, mixed martial artist

- Nikita Bedrin, racing driver

Twin towns – sister cities

Herne, Germany

Herne, Germany Niš, Serbia

Niš, Serbia /

/ Sevastopol, Russia (de facto), Ukraine (de jure)

Sevastopol, Russia (de facto), Ukraine (de jure) /

/ Yevpatoria, Russia (de facto), Ukraine (de jure)

Yevpatoria, Russia (de facto), Ukraine (de jure)

Former twin town:

Wakefield, United Kingdom. The tie was severed by the British city following the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine.[49]

Wakefield, United Kingdom. The tie was severed by the British city following the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine.[49]

Notes

References

- ^ a b c d e f g Law #248

- ^ a b Энциклопедия Города России. Moscow: Большая Российская Энциклопедия. 2003. p. 39. ISBN 5-7107-7399-9.

- ^ Charter of Belgorod, Article 26

- ^ "Мэр Белгорода ушел в отставку". www.rbc.ru (in Russian). 31 October 2022.

- ^ Charter of Belgorod, Article 35

- ^ a b c d Russian Federal State Statistics Service (2011). Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 года. Том 1 [2010 All-Russian Population Census, vol. 1]. Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 года [2010 All-Russia Population Census] (in Russian). Federal State Statistics Service.

- ^ Belgorod Oblast Territorial Branch of the Federal State Statistics Service. Численность населения Белгородской области по муниципальным образованиям на 1 января 2015 года Archived 18 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine (in Russian)

- ^ a b c Law #159

- ^ "Об исчислении времени". Официальный интернет-портал правовой информации (in Russian). 3 June 2011. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- ^ Почта России. Информационно-вычислительный центр ОАСУ РПО. (Russian Post). Поиск объектов почтовой связи (Postal Objects Search) (in Russian)

- ^ "Dialing Code for Belgorod - Russia".

- ^ Charter of Belgorod Oblast, Article 6

- ^ "Бєлгород".

- ^ a b Russian Federal State Statistics Service. Всероссийская перепись населения 2020 года. Том 1 [2020 All-Russian Population Census, vol. 1] (XLS) (in Russian). Federal State Statistics Service.

- ^ "History of Belgorod". rusmania.com. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- ^ Federal State Statistics Service (21 May 2004). Численность населения России, субъектов Российской Федерации в составе федеральных округов, районов, городских поселений, сельских населённых пунктов – районных центров и сельских населённых пунктов с населением 3 тысячи и более человек [Population of Russia, Its Federal Districts, Federal Subjects, Districts, Urban Localities, Rural Localities—Administrative Centers, and Rural Localities with Population of Over 3,000] (XLS). Всероссийская перепись населения 2002 года [All-Russia Population Census of 2002] (in Russian).

- ^ Всесоюзная перепись населения 1989 г. Численность наличного населения союзных и автономных республик, автономных областей и округов, краёв, областей, районов, городских поселений и сёл-райцентров [All Union Population Census of 1989: Present Population of Union and Autonomous Republics, Autonomous Oblasts and Okrugs, Krais, Oblasts, Districts, Urban Settlements, and Villages Serving as District Administrative Centers]. Всесоюзная перепись населения 1989 года [All-Union Population Census of 1989] (in Russian). Институт демографии Национального исследовательского университета: Высшая школа экономики [Institute of Demography at the National Research University: Higher School of Economics]. 1989 – via Demoscope Weekly.

- ^ "Том 4. Национальный состав и владение языками. Гражданство". Территориальный органФедеральной службы государственной статистикипо Белгородской области. Retrieved 24 May 2023.

- ^ "Национальный состав населения" (PDF). Территориальный органФедеральной службы государственной статистикипо Белгородской области. Retrieved 24 May 2023.

- ^ "Russia At a Glance. Belgorod". HED. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- ^ Сальникова О.Н. История Белгородской крепости на берегу реки Везелицы в контексте развития геодезического краеведения (in Russian).

- ^ П.М. Беляев, А.П. Чиченков (1962). Белгород: Очерк о прошлом, настоящем и будущем города (in Russian). pp. 150–154.

- ^ П.М. Беляев, А.П. Чиченков (1962). Белгород: Очерк о прошлом, настоящем и будущем города (in Russian). pp. 156–158.

- ^ "ИСТОРИЯ ГРАЖДАНСКОГО ПРОСПЕКТА — САМОЙ СТАРОЙ УЛИЦЫ БЕЛГОРОДА" (in Russian). Retrieved 30 October 2023.

- ^ "Письмо в редакцию по поводу "1000-летия" г. Белгорода" (in Russian). historybel.narod.ru. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- ^ "Belgorod Krepost". Sovitskaya Archeologia. 3: 262–264.

- ^ Зуев, Василий Федорович (1762). Путешественныя записки Василья Зуева от С. Петербурга до Херсона в 1781 и 1782 году (in Russian).

- ^ "КРАСОТА РЕГУЛЯРСТВА". ssafro-n.livejournal.com. 9 January 2013.

- ^ "Belgorod oblast meteodata". Archived from the original on 28 December 2011.

- ^ "Belgorod Climate". Archived from the original on 22 January 2016. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- ^ Khodarkovsky,Michael, "Russia's Steppe Frontier", 2002.

- ^ One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Byelgorod". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 4 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 895.

- ^ "Jüdisches Arbeitsbataillon Belgorod". Bundesarchiv.de (in German). Retrieved 15 June 2024.

- ^ "Belgorod :: Regions & Cities :: Russia-InfoCentre". russia-ic.com. Retrieved 20 July 2018.

- ^ "120 People Killed in Russian Border Region Since Invasion of Ukraine, Governor Says". The Moscow Times. 23 April 2024.

- ^ "Ukraine attacks Russian oil depot as Mariupol awaits evacuations and Putin's troops abandon Chernobyl". CBS News. 1 April 2022. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ^ Axe, David. "Ukrainian Attack Helicopters Just Slipped Into Russia And Blew Up A Fuel Depot". Forbes. Retrieved 1 April 2022.

- ^ Wright, George (21 April 2023). "Ukraine war: Russian warplane 'accidentally bombs own city'". BBC News. Retrieved 21 April 2023.

- ^ Lendon, Radina; Gigova, Victoria; Butenko, Josh; Pennington, Brad (21 April 2023). "Russian jet drops bomb on Russian city, state media says". CNN. Retrieved 21 April 2023.

- ^ "Russia's Belgorod sees mass evacuations over undetonated bomb". BBC News. 22 April 2023.

- ^ "How Belgorod has suffered from Ukraine's retaliation strikes". dw.com. Deutsche Welle. 9 January 2024.

- ^ "Russia Moves 5,000 Children From Belgorod After Kyiv Attacks". The Moscow Times. 30 March 2024.

- ^ "6 Killed in Ukrainian Drone Attack on Russia's Belgorod". The Moscow Times. 6 May 2024.

- ^ "Death Toll in Missile Attack on Russia's Belgorod Climbs to 16". The Moscow Times. 14 May 2024.

- ^ "CIT: Вероятно, дом в Белгороде был разрушен боеприпасом РФ – DW – 13.05.2024". dw.com (in Russian). Retrieved 28 May 2024.

- ^ ""Не знаю, во что верить". Какая ракета разрушила дом в Белгороде". Север.Реалии (in Russian). 14 May 2024. Retrieved 28 May 2024.

- ^ "Train Station in Belgorod" (in Russian). Archived from the original on 29 September 2013.

- ^ "Внешние связи". beladm.ru (in Russian). Belgorod. Archived from the original on 5 September 2011. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- ^ "Ukraine: Wakefield to sever ties with Russian twin city". BBC News. 28 February 2022. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

Sources

- Белгородский городской Совет депутатов. Решение №197 от 29 ноября 2005 г. «О принятии Устава городского округа "Город Белгород"», в ред. Решения №262 от 22 июля 2015 г. «О внесении изменений в Устав городского округа "Город Белгород"». Вступил в силу 1 января 2006 г. (за исключением отдельных положений). Опубликован: "Наш Белгород", №50, 16 декабря 2005 г. (Belgorod City Council of Deputies. Decision #197 of November 29, 2005 On the Adoption of the Charter of the Urban Okrug of the "City of Belgorod", as amended by the Decision #262 of July 22, 2015 On Amending the Charter of the Urban Okrug of the "City of Belgorod". Effective as of January 1, 2006 (with the exception of certain clauses).).

- Белгородская областная Дума. Закон №248 от 15 декабря 2008 г. «Об административно-территориальном устройстве Белгородской области», в ред. Закона №213 от 4 июля 2013 г. «О внесении изменения в Закон Белгородской области "Об административно-территориальном устройстве Белгородской области"». Вступил в силу по истечении 10 дней со дня официального опубликования за исключением положений, для которых предусмотрены иные сроки вступления в силу. Опубликован: "Белгородские известия", №219-220, 19 декабря 2008 г. (Belgorod Oblast Duma. Law #248 of December 15, 2008 On the Administrative-Territorial Structure of Belgorod Oblast, as amended by the Law #213 of July 4, 2013 On Amending the Law of Belgorod Oblast "On the Administrative-Territorial Structure of Belgorod Oblast". Effective as of 10 days after the day of the official publication; except for the portions for which other effective dates are specified.).

- Белгородская областная Дума. Закон №159 от 20 декабря 2004 г. «Об установлении границ муниципальных образований и наделении их статусом городского, сельского поселения, городского округа, муниципального района», в ред. Закона №244 от 4 декабря 2013 г. «О внесении изменения в статью 12 Закона Белгородской области "Об установлении границ муниципальных образований и наделении их статусом городского, сельского поселения, городского округа, муниципального района"». Вступил в силу по истечении 10 дней со дня официального опубликования. Опубликован: "Белгородские известия", №218–220, 24 декабря 2004 г. (Belgorod Oblast Duma. Law #159 of December 20, 2004 On Establishing the Borders of the Municipal Formations and on Granting Them a Status of Urban, Rural Settlement, Urban Okrug, Municipal District, as amended by the Law #244 of December 4, 2013 On Amending Article 12 of the Law of Belgorod Oblast "On Establishing the Borders of the Municipal Formations and on Granting Them a Status of Urban, Rural Settlement, Urban Okrug, Municipal District". Effective as of the day which is 10 days after the official publication.).

External links

Media related to Belgorod at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Belgorod at Wikimedia Commons- Official website (in Russian)

- Directory of organizations in Belgorod (in Russian)

- War in Ukraine: Russia accuses Ukraine of attacking oil depot. BBC News, 1 April 2022