ACF Fiorentina

| ||||

| Full name | ACF Fiorentina S.r.l.[1][2] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nickname(s) | I Viola (The Purples / The Violets) I Gigliati (The Lilies) | |||

| Founded | 29 August 1926, as Associazione Calcio Fiorentina 1 August 2002, as Florentia Viola then ACF Fiorentina | |||

| Ground | Stadio Artemio Franchi | |||

| Capacity | 43,147[3] | |||

| Owner | New ACF Fiorentina S.r.l. | |||

| Chairman | Rocco B. Commisso | |||

| Head coach | Raffaele Palladino | |||

| League | Serie A | |||

| 2023–24 | Serie A, 8th of 20 | |||

| Website | acffiorentina.com | |||

|

| ||||

| Active teams of ACF Fiorentina |

|---|

Associazione Calcio Fiorentina,[1][2] commonly referred to as Fiorentina (pronounced [fjorenˈtiːna]), is an Italian professional football club based in Florence, Tuscany. The original team was founded by a merger in August 1926, while the current club was refounded in August 2002 following bankruptcy. Fiorentina have played at the top level of Italian football for the majority of their existence; only four clubs have played in more Serie A seasons.

Fiorentina has won two Italian league titles, in 1955–56 and again in 1968–69, as well as six Coppa Italia trophies and one Supercoppa Italiana. On the European stage, Fiorentina won the UEFA Cup Winners' Cup in 1960–61. They also lost five finals, finishing runners-up in the 1956–57 European Cup (the first Italian team to reach the final in the top continental competition), the 1961–62 Cup Winners' Cup, the 1989–90 UEFA Cup, and in the 2022–23 and 2023–24 editions of the UEFA Conference League, being the first club to record two consecutive final appearances and two consecutive defeats in the competition's history.

Fiorentina is one of fifteen European teams that have played in the finals of all three major continental competitions (the European Cup/Champions League, the UEFA Cup Winners' Cup and the UEFA Cup/Europa League) and in 2023, by reaching the Europa Conference League final, Fiorentina became the first team to reach all four major European club competition finals (excluding the one-off match of the UEFA Super Cup).

Since 1931, the club have played at the Stadio Artemio Franchi, which currently has a capacity of 43,147. The stadium has used several names over the years and has undergone several renovations. Fiorentina are known widely by the nickname Viola, a reference to their distinctive purple colours.[4]

History

[edit]Foundation prior to World War II

[edit]

Associazione Calcio Fiorentina was founded in the autumn of 1926 by local noble and National Fascist Party member Luigi Ridolfi Vay da Verrazzano,[5] who initiated the merger of two older Florentine clubs, CS Firenze and PG Libertas. The aim of the merger was to give Florence a strong club to rival those of the more dominant Italian Football Championship sides of the time from Northwest Italy. Also influential was the cultural revival and rediscovery of Calcio Fiorentino, an ancestor of modern football that was played by members of the Medici family.[5]

After a rough start and three seasons in lower leagues, Fiorentina reached Serie A in 1931. That same year saw the opening of the new stadium, originally named after Giovanni Berta, a prominent fascist, but now known as Stadio Artemio Franchi. At the time, the stadium was a masterpiece of engineering, and its inauguration was monumental. To be able to compete with the best teams in Italy, Fiorentina strengthened their team with some new players, notably the Uruguayan Pedro Petrone, nicknamed el Artillero. Despite enjoying a good season and finishing in fourth place, Fiorentina were relegated the following year, although they would return quickly to Serie A. In 1941, they won their first Coppa Italia, but the team were unable to build on their success during the 1940s due to World War II and other troubles.

First scudetto and '50–'60s

[edit]

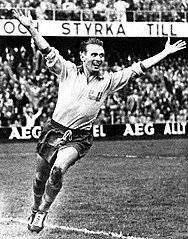

In 1950, Fiorentina started to achieve consistent top-five finishes in the domestic league. The team consisted of players such as well-known goalkeeper Giuliano Sarti, Sergio Cervato, Francesco Rosella, Guido Gratton, Giuseppe Chiappella, Aldo Scaramucci, Brazilian Julinho, and Argentinian Miguel Montuori. This team won Fiorentina's first scudetto (Italian championship) in 1955–56, 12 points ahead of second-place Milan. Milan beat Fiorentina to top spot the following year. Fiorentina became the first Italian team to play in a European Cup final, when a disputed penalty led to a 2–0 defeat at the hands of Alfredo Di Stéfano's Real Madrid. Fiorentina were runners-up again in the three subsequent seasons. In the 1960–61 season, the club won the Coppa Italia again and was also successful in Europe, winning the first Cup Winners' Cup against Scottish side Rangers.

After several years of runner-up finishes, Fiorentina dropped away slightly in the 1960s, bouncing from fourth to sixth place, although the club won the Coppa Italia and the Mitropa Cup in 1966.

Second scudetto and '70s

[edit]While the 1960s did result in some trophies and good Serie A finishes for Fiorentina, nobody believed that the club could challenge for the title. The 1968–69 season started with Milan as frontrunners, but on matchday 7, it lost to Bologna and was overtaken by Gigi Riva's Cagliari. Fiorentina, after an unimpressive start, then moved to the top of the Serie A, but the first half of its season finished with a 2–2 draw against Varese, leaving Cagliari as outright league leader. The second half of the season was a three-way battle between the three contending teams, Milan, Cagliari and Fiorentina. Milan fell away, instead focusing its efforts on the European Cup, and it seemed that Cagliari would retain top spot. After Cagliari lost against Juventus, however, Fiorentina took over at the top. The team then won all of its remaining matches, beating rivals Juve in Turin on the penultimate matchday to seal its second, and last, national title. In the European Cup competition the following year, Fiorentina had some good results, including a win in the Soviet Union against Dynamo Kyiv, but was eventually knocked out in the quarter-finals after a 3–0 defeat in Glasgow to Celtic.[6]

Viola players began the 1970s decade with scudetto sewed on their breast, but the period was not especially fruitful for the team. After a fifth-place finish in 1971, they finished in mid-table almost every year, even flirting with relegation in 1972 and 1978. The Viola did win the Anglo-Italian League Cup in 1974 and won the Coppa Italia again in 1975. The team consisted of young talents like Vincenzo Guerini and Moreno Roggi, who suffered bad injuries, and above all Giancarlo Antognoni, who would later become an idol to Fiorentina's fans. The young average age of the players led to the team being called "Fiorentina Ye-Ye".

Pontello era

[edit]In 1980, Fiorentina was bought by Flavio Pontello, who came from a rich housebuilding family. He quickly changed the team's anthem and logo, leading to some complaints by the fans, but he started to bring in high-quality players such as Francesco Graziani and Eraldo Pecci from Torino; Daniel Bertoni from Sevilla; Daniele Massaro from Monza; and a young Pietro Vierchowod from Como. The team was built around Giancarlo Antognoni, and in 1982, Fiorentina were involved in an exciting duel with rivals Juventus. After a bad injury to Antognoni, the league title was decided on the final day of the season when Fiorentina were denied a goal against Cagliari and were unable to win. Juventus won the title with a disputed penalty and the rivalry between the two teams erupted.

The following years were strange for Fiorentina, who vacillated between high finishes and relegation battles. Fiorentina also bought two interesting players, El Puntero Ramón Díaz and, most significantly, the young Roberto Baggio.

In 1990, Fiorentina fought to avoid relegation right up until the final day of the season, but did reach the UEFA Cup final, where they again faced Juventus. The Turin team won the trophy, but Fiorentina's tifosi once again had real cause for complaint: the second leg of the final was played in Avellino (Fiorentina's home ground was suspended), a city with many Juventus fans, and emerging star Roberto Baggio was sold to the rival team on the day of the final. Pontello, suffering from economic difficulties, was selling all the players and was forced to leave the club after serious riots in Florence's streets. The club was then acquired by the famous filmmaker Mario Cecchi Gori.

Cecchi Gori era: from Champions League to bankruptcy

[edit]

The first season under Cecchi Gori's ownership was one of stabilisation, after which the new chairman started to sign some good players like Brian Laudrup, Stefan Effenberg, Francesco Baiano and, most importantly, Gabriel Batistuta, who became an iconic player for the team during the 1990s. In 1993, however, Cecchi Gori died and was succeeded as chairman by his son, Vittorio. Despite a good start to the season, Cecchi Gori fired the coach, Luigi Radice, after a defeat against Atalanta,[7] and replaced him with Aldo Agroppi. The results were dreadful: Fiorentina fell into the bottom half of the standings and were relegated on the last day of the season.

Claudio Ranieri was brought in as coach for the 1993–94 season, and that year, Fiorentina dominated Serie B, Italy's second division. Upon their return to Serie A, Ranieri put together a good team centred around new top scorer Batistuta, signing the young talent Rui Costa from Benfica and the new world champion Brazilian defender Márcio Santos. The former became an idol to Fiorentina fans, while the second disappointed and was sold after only a season. The Viola finished the season in tenth place.

The following season, Cecchi Gori bought other important players, namely Swedish midfielder Stefan Schwarz. The club again proved its mettle in cup competitions, winning the Coppa Italia against Atalanta and finishing joint-third in Serie A. In the summer, Fiorentina became the first non-national champions to win the Supercoppa Italiana, defeating Milan 2–1 at the San Siro.

Fiorentina's 1996–97 season was disappointing in the league, but they did reach the Cup Winners' Cup semi-final by beating Gloria Bistrița, Sparta Prague and Benfica. The team lost the semi-final to the eventual winner of the competition, Barcelona (away 1–1; home 0–2). The season's main signings were Luís Oliveira and Andrei Kanchelskis, the latter of whom suffered from many injuries.

At the end of the season, Ranieri left Fiorentina for Valencia in Spain, with Cecchi Gori appointing Alberto Malesani as his replacement. Fiorentina played well but struggled against smaller teams, although they did manage to qualify for the UEFA Cup. Malesani left Fiorentina after only a season and was succeeded by Giovanni Trapattoni. With Trapattoni's expert guidance and Batistuta's goals, Fiorentina challenged for the title in 1998–99 but finished the season in third, earning them qualification for the Champions League. The following year was disappointing in Serie A, but Viola played some historical matches in the Champions League, beating Arsenal 1–0 at the old Wembley Stadium and Manchester United 2–0 in Florence. They were ultimately eliminated in the second group stage.

At the end of the season, Trapattoni left the club and was replaced by Turkish coach Fatih Terim. More significantly, however, Batistuta was sold to Roma, who eventually won the title the following year. Fiorentina played well in 2000–01 and stayed in the top half of Serie A, despite the resignation of Terim and the arrival of Roberto Mancini. They also won the Coppa Italia for the sixth and last time.

The year 2001 heralded major changes for Fiorentina, as the terrible state of the club's finances was revealed: they were unable to pay wages and had debts of around US$50 million. The club's owner, Vittorio Cecchi Gori, was able to raise some more money, but this soon proved to be insufficient to sustain the club. Fiorentina were relegated at the end of the 2001–02 season and went into judicially-controlled administration in June 2002. This form of bankruptcy (sports companies cannot exactly fail in this way in Italy, but they can suffer a similar procedure) meant that the club was refused a place in Serie B for the 2002–03 season, and as a result effectively ceased to exist.

Della Valle era: from fourth tier to Europe (2000s and 2010s)

[edit]The club was promptly re-established in August 2002 as Associazione Calcio Fiorentina e Florentia Viola with shoe and leather entrepreneur Diego Della Valle as new owner and the club was admitted into Serie C2, the fourth tier of Italian football. The only player to remain at the club in its new incarnation was Angelo Di Livio, whose commitment to the club's cause further endeared him to the fans. Helped by Di Livio and 30-goal striker Christian Riganò, the club won its Serie C2 group with considerable ease, which would normally have led to a promotion to Serie C1. Due to the bizarre Caso Catania (Catania Case), the club skipped Serie C1 and was admitted into Serie B, something that was only made possible by the Italian Football Federation (FIGC)'s decision to resolve the Catania situation by increasing the number of teams in Serie B from 20 to 24 and promoting Fiorentina for "sports merits".[8] In the 2003 off-season, the club also bought back the right to use the Fiorentina name and the famous shirt design, and re-incorporated itself as ACF Fiorentina. The club finished the 2003–04 season in sixth place and won the playoff against Perugia to return to top-flight football.

In their first season back in Serie A, the club struggled to avoid relegation, only securing survival on the last day of the season on head-to-head record against Bologna and Parma. In 2005, Della Valle decided to appoint Pantaleo Corvino as new sports director, followed by the appointment of Cesare Prandelli as head coach in the following season. The club made several signings during the summer transfer market, most notably Luca Toni and Sébastien Frey. This drastic move earned them a fourth-place finish with 74 points and a Champions League qualifying round ticket. Toni scored 31 goals in 38 appearances, the first player to pass the 30-goal mark since Antonio Valentin Angelillo in the 1958–59 season, for which he was awarded the European Golden Boot. On 14 July 2006, Fiorentina were relegated to Serie B due to their involvement in the Calciopoli scandal and given a 12-point penalty. The team was reinstated to the Serie A on appeal, but with a 19-point penalty for the 2006–07 season. The team's 2006–07 Champions League place was also revoked.[9] After the start of the season, Fiorentina's penalisation was reduced from 19 points to 15 on appeal to the Italian courts. In spite of this penalty, they managed to secure a place in the UEFA Cup.

Despite Toni's departure to Bayern Munich, Fiorentina had a strong start to the 2007–08 season and were tipped by Italy national team head coach Marcello Lippi, among others, as a surprise challenger for the scudetto,[10] and although this form tailed off towards the middle of the season, the Viola managed to qualify for the Champions League. In Europe, the club reached the semi-final of the UEFA Cup, where they were ultimately defeated by Rangers on penalties. The 2008–09 season continued this success, a fourth-place finish assuring Fiorentina's spot in 2010's Champions League playoffs. Their European campaign was also similar to that of the previous run, relegated to the 2008–09 UEFA Cup and were eliminated by Ajax in the end.

In the 2009–10 season, Fiorentina started their domestic campaign strongly before steadily losing momentum and slipped to mid-table positions at the latter half of the season. In Europe, the team proved to be a surprise dark horse: after losing their first away fixture against Lyon, they staged a comeback with a five-match streak by winning all their remaining matches (including defeating Liverpool home and away). The Viola qualified as group champions, but eventually succumbed to Bayern Munich due to the away goals rule. This was controversial due to a mistaken refereeing decision by Tom Henning Øvrebø, who allowed a clearly offside goal for Bayern in the first leg. Bayern eventually finished the tournament as runners-up, making a deep run all the way to the final. The incident called into attention the possible implementation of video replays in football. Despite a good European run and reaching the semi-finals in the Coppa Italia, Fiorentina failed to qualify for Europe.

During this period, on 24 September 2009, Andrea Della Valle resigned from his position as chairman of Fiorentina, and announced all duties would be temporarily transferred to Mario Cognini, Fiorentina's vice-president until a permanent position could be filled.[11]

In June 2010, the Viola bid farewell to long-time manager Cesare Prandelli, by then the longest-serving coach in the team's history, who was departing to coach the Italy national team. Catania manager Siniša Mihajlović was appointed to replace him. The club spent much of the early 2010–11 season in last place, but their form improved and Fiorentina ultimately finished ninth. Following a 1–0 defeat to Chievo in November 2011, Mihajlović was sacked and replaced by Delio Rossi.[12] After a brief period of improvements, the Viola were again fighting relegation, prompting the sacking of Sporting Director Pantaleo Corvino in early 2012 following a 0–5 home defeat to Juventus. Their bid for survival was kept alive by a number of upset victories away from home, notably at Roma and Milan. During a home game against Novara, trailing 0–2 within half an hour, manager Rossi decided to substitute midfielder Adem Ljajić early. Ljajić sarcastically applauded him in frustration, whereupon Rossi retaliated by physical assaulting his player, an action that ultimately prompted his termination by the club.[13] His replacement, caretaker manager Vincenzo Guerini, then guided the team away from the relegation zone to a 13th-place finish to end the turbulent year.

To engineer a resurrection of the club after the disappointing season, the Della Valle family invested heavily in the middle of 2012, buying 17 new players and appointing Vincenzo Montella as head coach. The team began the season well, finishing the calendar year in joint third place and eventually finishing the 2012–13 season in fourth, enough for a position in the 2013–14 Europa League.

The club lost fan favourite Stevan Jovetić during the middle of 2013, selling him to English Premier League club Manchester City for a €30 million transfer fee. They also sold Adem Ljajić to Roma and Alessio Cerci to Torino, using the funds to bring in Mario Gómez, Josip Iličić and Ante Rebić, among others. During the season, Fiorentina topped their Europa League group, moving on to the round of 32 to face Danish side Esbjerg fB, which Fiorentina defeated 4–2 on aggregate. In the following round of 16, however, they then lost to Italian rivals Juventus 2–1 on aggregate, ousting Fiorentina from the competition. At the end of the season, the team finished fourth again in the league, and also finishing the year as Coppa Italia runners-up after losing 3–1 to Napoli in the final.

In 2014–15, during the 2015 winter transfer window, the team club sold star winger Juan Cuadrado to Chelsea for €30 million but were able to secure the loan of Mohamed Salah in exchange, who was a revelation in the second half of the season. Their 2014–15 Europa League campaign saw them progress to the semi-finals, where they were knocked-out by Spanish side Sevilla, the eventual champions. In the 2014–15 domestic season, Fiorentina once again finished fourth, thus qualifying for the 2015–16 Europa League. In June 2015, Vincenzo Montella was sacked as manager after the club grew impatient with the coaches inability to prove his commitment to the club,[14] and was replaced by Paulo Sousa, who lasted until June 2017 and the appointment of Stefano Pioli.[15] Club captain Davide Astori died suddenly at the age of 31 in March 2018.[16] Astori had suffered a cardiac arrest while in a hotel room before an away game. The club subsequently retired Astori's kit number, 13.[17] Fiorentina suffered during the 2018–19 Serie A campaign and ended the season on a 14 match winless streak, finishing in 16th place with only 41 points, 3 points from the relegation zone. On 9 April 2019, Pioli resigned as manager and was replaced by Montella.[18]

Commisso era

[edit]On 6 June 2019, the club was sold to Italian-American billionaire Rocco Commisso for around 160 million euros.[19] The sale marked the end of the Della Valle family's seventeen-year association with the club.[20] Vincenzo Montella was confirmed as coach for the first season of the new era despite the team's poor end to the previous campaign, which saw them finish only three points clear of the relegation zone.[21] Fiorentina continued their struggles from the previous year, spending the majority of the season in lower midtable. Montella was sacked on 21 December after a 7 match winless run which left the club in 15th place, and was replaced by Giuseppe Iachini. In November 2020 Cesare Prandelli returned to Fiorentina, replacing Giuseppe Iachini as coach.[22]

Under coach Vincenzo Italiano, who arrived in 2021, Fiorentina reached and lost two consecutive finals of the UEFA Europa Conference League, in the 2022–23 and 2023–24 editions, being the first club to record two consecutive final appearances in the competition's history, and becoming the first team to lose two consecutive European finals since Benfica in 2013 and 2014 UEFA Europa League finals.[23]

Players

[edit]Current squad

[edit]- As of 1 October 2024[24]

Note: Flags indicate national team as defined under FIFA eligibility rules; some limited exceptions apply. Players may hold more than one non-FIFA nationality.

|

|

Fiorentina Primavera

[edit]- As of 2 September 2024[24]

Note: Flags indicate national team as defined under FIFA eligibility rules; some limited exceptions apply. Players may hold more than one non-FIFA nationality.

|

|

Other players under contract

[edit]- As of 7 September 2024[24]

Note: Flags indicate national team as defined under FIFA eligibility rules; some limited exceptions apply. Players may hold more than one non-FIFA nationality.

|

Out on loan

[edit]- As of 1 October 2024[24]

Note: Flags indicate national team as defined under FIFA eligibility rules; some limited exceptions apply. Players may hold more than one non-FIFA nationality.

|

|

Notable players

[edit]Retired numbers

[edit]- 13

Davide Astori, defender (2015–18) – posthumous honour[25]

Davide Astori, defender (2015–18) – posthumous honour[25]

Management staff

[edit]| Position | Staff |

|---|---|

| Head coach | |

| Assistant coach | |

| Athletic coach | |

| Goalkeeping coach | |

| Technical coach | |

| Match analyst | |

| Head of medical staff | |

| Club doctor | |

| Head of physiotherapists | |

| First team doctor | |

| Physiotherapist | |

| Nutritionist | |

| Kit manager | |

| Sporting director | |

| Technical director | |

| Secretary |

Managerial history

[edit]Fiorentina have had many managers and head coaches throughout their history. Below is a chronological list from the club's foundation in 1926 to the present day.[26]

|

|

|

Colours and badge

[edit]Badge

[edit]

The official emblem of the city of Florence, a red fleur-de-lis on a white field, has been the staple in the all-round symbolism of the club.[27]

Over the course of the club's history, they have had several badge changes, all of which incorporated Florence's fleur-de-lis in some way.[28] The first one was nothing more than the city's coat of arms, a white shield with the red fleur-de-lis inside.[29][27] It was soon changed to a very stylised fleur-de-lis, always red, and sometimes even without the white field.[27] The most common symbol, adopted for about 20 years, had been a white lozenge with the flower inside.[27] During the season they were Italian champions, the lozenge disappeared and the flower was overlapped with the scudetto.[30]

The logo introduced by owner Flavio Pontello in 1980 was particularly distinct, consisting of one-half of the city of Florence's emblem and one-half of the letter "F", for Fiorentina. People disliked it when it was introduced, believing it was a commercial decision and, above all, because the symbol bore more of a resemblance to a halberd than a fleur-de-lis.[28]

Until the 2022–23 season, when the club unveiled a new, stylistically simplified badge, the logo was a kite shaped double lozenge bordered in gold. The outer lozenge had a purple background with the letters "AC" in white and the letter "F" in red, standing for the club's name. The inner lozenge was white with a gold border and the red Giglio of Florence.[28] This logo had been in use from 1992 to 2002, but after the financial crisis and resurrection of the club the new one couldn't use the same logo.[29] Florence's comune instead granted Florentia Viola use of the stylised coat of arms used in other city documents.[29] Diego Della Valle acquired the current logo the following year in a judicial auction for a fee of €2.5 million, making it the most expensive logo in Italian football.[29]

Kit and colours

[edit]

When Fiorentina was founded in 1926, the players wore red and white halved shirts derived from the colour of the city emblem.[31] The more well-known and highly distinctive purple kit was adopted in 1928 and has been used ever since, giving rise to the nickname La Viola ("The Purple (team)").[32] Tradition has it that Fiorentina got their purple kit by mistake after an accident washing the old red and white coloured kits in the river.[33]

The away kit has always been predominantly white, sometimes with purple and red elements, sometimes all-white.[27] The shorts had been purple when the home kit was with white shorts.[32] In the 1995–96 season, it was all-red with purple borders and two lilies on the shoulders.[34] The red shirt has been the most worn 3rd shirt by Fiorentina, although they also wore rare yellow shirts ('97–'98, '99–'00 and '10–'11) and a sterling version, mostly in the Coppa Italia, in 2000–01.[27]

For the 2017–18 season and the first time in its history, the club used five kits during the season, composing of one home kit (all-purple) and four away kits, each one representing one historic quartiere of the city of Florence: all-blue (Santa Croce), all-white (Santo Spirito), all-green (San Giovanni) and all-red (Santa Maria Novella).[35]

Anthem

[edit]"Canzone Viola" (Purple Song) is the title of the Fiorentina's song, nowadays better known as "Oh Fiorentina".[36] It is the oldest official football anthem in Italy and one of the oldest in the world.[citation needed] Dated 1930 and born only four years after the creation of the club, the song was written by a 12-year-old child, Enzo Marcacci, and musically arranged by maestro Marco Vinicio.[citation needed] It was published for the first time by the publisher Marcello Manni, who later became the owner of the rights.[citation needed] It soon achieved notoriety thanks to the printed media and the Ordine del Marzocco, a sort of original viola-club, which printed the lyrics of the song and distributed it to a home match on November 22, 1931.[37]

The song was recorded by Narciso Parigi in 1959 and again in 1965; the latter version replaced the original edition as the Fiorentina anthem.[citation needed] Subsequently, Narciso Parigi himself acquired the ownership of the rights, which he donated in 2002 to the supporter club Collettivo Autonomo Viola.[36]

Kit suppliers and shirt sponsors

[edit]| Period | Kit manufacturer | Shirt sponsor (front) | Shirt sponsor (secondary) | Shirt sponsor (back) | Shirt sponsor (sleeve) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1978–1981 | Adidas | None | None | None | None |

| 1981–1983 | J.D. Farrow's | J.D. Farrow's | |||

| 1983–1986 | Ennerre[38] | Opel | |||

| 1986–1988 | Crodino | ||||

| 1988–1989 | ABM[39] | ||||

| 1989–1991 | La Nazione | ||||

| 1991–1992 | Lotto | Giocheria[40][41] | |||

| 1992–1993 | 7 Up | ||||

| 1993–1994 | Uhlsport | ||||

| 1994–1995 | Sammontana | ||||

| 1995–1997 | Reebok | ||||

| 1997–1999 | Fila | Nintendo | |||

| 1999–2000 | Toyota | ||||

| 2000–2001 | Diadora | ||||

| 2001–2002 | Mizuno | ||||

| 2002–2003 | Garman / Puma | La Fondiaria / Fondiaria Sai | |||

| 2003–2004 | Adidas | Fondiaria Sai | |||

| 2004–2005 | Toyota | ||||

| 2005–2010 | Lotto | ||||

| 2010–2011 | Save the Children (Matchday 1-18) / Mazda (Matchday 19-38) | Save the Children (Matchday 19-38) | |||

| 2011–2012 | Mazda | Save the Children | |||

| 2012–2014 | Joma | ||||

| 2014–2015 | Save the Children | None | |||

| 2015–2016 | Le Coq Sportif | ||||

| 2016–2018 | Folletto / Vorwerk (Europa League) | Save the Children | |||

| 2018–2019 | Save the Children | Dream Loud Entertainment | New Generation Mobile | ||

| 2019–2020 | Mediacom | Val di Fassa / Meyer Children's Hospital | Prima Assicurazioni | Estra | |

| 2020–2022 | Kappa | None | |||

| 2022–2024 | Lamioni Holding | None | |||

| 2024– | Betway Scores |

Official partners

[edit]- EA Sports – Football video gaming partner

- Montezemolo – Fashion partner

- Gruppoaf – Official partner

- Sammontana – Official ice cream

- Synlab – Health partner

- OlyBet.tv – Infotainment partner[42]

Honours

[edit]National titles

[edit]European titles

[edit]- UEFA Champions League:

- Runners-up (1): 1956–57

- UEFA Europa League:

- Runners-up (1): 1989–90

- Mitropa Cup

- Winners (1): 1966

Other titles

[edit]- Coppa Grasshoppers

- Winners: 1957

- Anglo-Italian League Cup

- Winners: 1975

Divisional movements

[edit]| Series | Years | Last | Pror around 160 million euros.motions | Relegations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 85 | 2023–24 | – | |

| B | 5 | 2003–04 | bankruptcy[43] | |

| C | 1 | 2002–03 | never | |

| 91 years of professional football in Italy since 1929 | ||||

Fiorentina as a company

[edit]A.C. Fiorentina S.p.A. was unable to register for 2002–03 Serie B due to financial difficulties, and then the sports title was transferred to a new company thanks to Article 52 of N.O.I.F., while the old company was liquidated. At that time the club was heavily relying on windfall profit from selling players, especially in pure player swap or cash plus player swap that potentially increased the cost by the increase in amortisation of player contracts (an intangible assets). For example, Marco Rossi joined Fiorentina for Lire 17 billion in 2000, but at the same time Lorenzo Collacchioni moved to Salernitana for Lire 1 billion, meaning the club had a player profit of Lire 997 million and extra Lire 1 billion to be amortised in 5-years.[44] In 1999, Emiliano Bigica also swapped with Giuseppe Taglialatela,[45] which the latter was valued for Lire 10 billion.[44] The operating income (excluding windfall profit from players trading) of 2000–01 season was minus Lire 113,271,475,933 (minus €58,499,835).[44] It was only boosted by the sales of Francesco Toldo and Rui Costa in June 2001 (a profit of Lire 134.883 billion; €69.661 million).[44] However, it was alleged they were to transfer to Parma[44] for a reported Lire 140 million.[46] The two players eventually joined Inter Milan and A.C. Milan in 2001–02 financial year instead, for undisclosed fees. Failing to have financial support from the owner Vittorio Cecchi Gori, the club was forced to windup due to its huge imbalance in operating income.

Since re-established in 2002, ACF Fiorentina S.p.A. are yet to self-sustain to keep the team in top division as well as in European competitions. In the 2005 financial year, which cover the first Serie A season, the club made a net loss of €9,159,356,[47] followed by a net loss of €19,519,789. In 2006 (2005–06 Serie A and 2006–07 Serie A), Fiorentina heavily invested on players, meaning the amortisation of intangible asset (the player contract) had increased from €17.7 million to €24 million.[48] However the club suffered from the 2006 Italian football scandal, which meant the club did not qualify for Europe. In 2007 Fiorentina almost broke-even, with a net loss of just €3,704,953. In the 2007 financial year the TV revenue increased after they qualified to the 2007–08 UEFA Cup.[49] Despite qualifying to the 2008–09 UEFA Champions League, Fiorentina made a net loss of €9,179,484 in 2008 financial year after the increase in TV revenue was outweighed by the increase in wage.[50] In the 2009 financial year, Fiorentina made a net profit of €4,442,803, largely due to the profit on selling players (€33,631,489 from players such as Felipe Melo, Giampaolo Pazzini and Zdravko Kuzmanović; increased from about €3.5 million in 2008). However it was also offset by the write-down of selling players (€6,062,545, from players such as Manuel da Costa, Arturo Lupoli and Davide Carcuro).[51]

After the club failed to qualify to Europe at the end of 2009–10 Serie A, as well as lack of player profit, Fiorentina turnover was decreased from €140,040,713 in 2009 to just €79,854,928, despite the wage bill also falling, la Viola still made a net loss of €9,604,353.[52][53] In the 2011 financial year, the turnover slipped to €67,076,953, as the club's lack of capital gains from selling players and 2010 financial year still included the instalments from UEFA for participating 2009–10 UEFA Europa League. Furthermore, the gate income had dropped from €11,070,385 to €7,541,260. The wage bill did not fall much and in reverse the amortisation of transfer fee had sightly increased due to new signings. La Viola had savings in other costs but counter-weighted by huge €11,747,668 write-down for departed players, due to D'Agostino, Frey and Mutu, but the former would counter-weight by co-ownership financial income, which all made the operating cost remained high as worse as last year. Moreover, in 2010 the result was boosted by acquiring the asset from subsidiary (related to AC Fiorentina) and the re-valuation of its value in separate balance sheet. If deducting that income (€14,737,855), 2010 financial year was net loss 24,342,208 and 2011 result was worse with €8,131,876 only in separate balance sheet.[54][55] In 2012, the club benefited from the sales of Matija Nastasić and Valon Behrami,[56][57] followed by Stevan Jovetić and Adem Ljajić in 2013.[58][59] In 2014, due to €28.4 million drop from the windfall profit of selling players, the club recorded their worst financial results since re-foundation, despite the fact the club maintained the same level of windfall profit, the result was still worse than in 2013.[60][61][62] Moreover, Fiorentina also revealed that the club had a relevant football net income of minus €19.5 million in the first assessment period of UEFA Financial Fair Play Regulations in the 2013–14 season (in May 2014).[63] (aggregate of 2012 and 2013 results), which within the limit of minus €45 million, as well as minus €25.5 million in assessment period 2014–15 (aggregate of 2012, 2013 and 2014 results). However, as the limit was reduced to minus €30 million in assessment period 2015–16, 2016–17 and 2017–18 season, the club had to achieve a relevant net income of positive €5.6 million in 2015 financial year. La Viola sold Juan Cuadrado to Chelsea in January 2015 for €30 million fee, to make the club eligible to 2016–17 edition of UEFA competitions.[60]

| Financial year | Turnover | Result | Total assets | Net assets | Re-capitalization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A.C. Fiorentina S.p.A. (PI 0039250485) exchange rate €1 = Lire 1936.27 | |||||

| 1999–2000[44] | €85,586,138# | €5,550,939 | €184,898,223 | €13,956,954 | |

| 2000–01[44] | €0 | ||||

| 2001–02 | Not available due to bankruptcy | ||||

| ACF Fiorentina S.p.A. (PI 05248440488) startup capital: €7,500,000 | |||||

| 2002–03 | (€6,443,549) | €4.2 million | |||

| 2003 (Jul–Dec) | |||||

| 2004[47] | €33,336,444 | €99,357,403 | |||

| 2005[48] | |||||

| 2006[48] | |||||

| 2007[49] | |||||

| 2008[50] | |||||

| 2009[51] | |||||

| 2010[52] | |||||

| 2011[55] | |||||

| 2012[56] | |||||

| 2013[58] | |||||

| 2014[60] | |||||

| Aggregate | (€134,207,148) | / | / | €203.9 million | |

| Average | (€10,736,572) | €58,149,609 | €16.312 million | ||

| Note: #Windfall profit from selling players excluded Italian accounting standards was changed over the years | |||||

League history

[edit]- 1926–1928: Prima Divisione (2nd tier)

- 1928–1929: Divisione Nazionale (1st tier)

- 1929–1931: Serie B (2nd tier) – Champions: 1931

- 1931–1938: Serie A (1st tier)

- 1938–1939: Serie B (2nd tier) – Champions: 1939

- 1939–1943: Serie A (1st tier)

- 1943–1946: no contests (WW II)

- 1946–1993: liga 1 (1st tier) – Champions: 1956, 1969

- 1993–1994: Serie B (2nd tier) – Champions: 1994

- 1994–2002: Serie A (1st tier)

- 2002–2003: Serie C2 (4th tier) – Champions: 2003

- 2003–2004: Serie B (2nd tier)

- 2004–present: Serie A (1st tier)

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Organigramma" (in Italian). AC Fiorentina Fiorentina. Archived from the original on 26 July 2008. Retrieved 29 November 2009.

- ^ a b "Fiorentina" (in Italian). Lega Calcio. Archived from the original on 25 February 2009. Retrieved 18 February 2009.

- ^ "ViolaChannel – Stadio Franchi". Archived from the original on 4 October 2013. Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- ^ "Rocco Commisso bought a football club. Then the trouble started". Financial Times. 13 January 2022. Archived from the original on 10 February 2023. Retrieved 10 February 2023.

- ^ a b Martin, Simon (September 2004). Football and Fascism: The National Game Under Mussolini. Berg Publishers. ISBN 1-85973-705-6.

- ^ "Prediksi Skor Serie A, Fiorentina Vs Genoa 29 Januari 2017". Viralbola.com. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- ^ "Archivio Corriere della Sera". Archived from the original on 5 November 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2009.

- ^ "Serie B a 24 squadre. C'è anche la Fiorentina". La Repubblica (in Italian). 20 August 2003. Archived from the original on 1 May 2008. Retrieved 4 April 2008.

- ^ "Italian trio relegated to Serie B". BBC News. 14 July 2006. Archived from the original on 14 July 2006. Retrieved 1 January 2010.

- ^ "Lippi Tips Fiorentina For Surprise Scudetto Challenge". Goal.com. 11 November 2007. Archived from the original on 10 November 2007. Retrieved 7 November 2007.

- ^ "Fiorentina senza presidente Della Valle si è dimesso". La Gazzetta dello Sport (in Italian). 24 September 2009. Archived from the original on 15 March 2010. Retrieved 24 September 2009.

- ^ "Mihajlovic sacked as Fiorentina coach". CNN. 7 November 2011. Archived from the original on 12 November 2011. Retrieved 7 August 2012.

- ^ "Fiorentina boss Delio Rossi sacked for attacking player". BBC Sport. 3 May 2012. Archived from the original on 14 May 2014. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- ^ "Official: Fiorentina sack Montella – Football Italia". 8 June 2015. Archived from the original on 9 June 2015. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- ^ "Stefano Pioli: Fiorentina hire former Inter Milan and Lazio boss". BBC Sport. 7 June 2017. Archived from the original on 18 October 2017. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- ^ McLaughlin, Elliot C. (4 March 2018). "Fiorentina captain Davide Astori dies of 'sudden illness' at 31, team says". CNN. Archived from the original on 6 March 2018. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- ^ Fiorentina, A. C. F. (6 March 2018). "Per onorarne la memoria e rendere indelebile il ricordo di Davide Astori, @CagliariCalcio e Fiorentina hanno deciso di ritirare congiuntamente la maglia con il numero 13. #DA13pic.twitter.com/KXP6s8WFlG". @acffiorentina (in Italian). Archived from the original on 9 November 2020. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- ^ "UFFICIALE: Fiorentina, Pioli s'è dimesso. Oggi seduta affidata al suo vice" (in Italian). Archived from the original on 21 January 2021. Retrieved 9 April 2019.

- ^ "U.S. billionaire Commisso buys Italy's Fiorentina". Reuters. 6 June 2019. Archived from the original on 1 July 2019. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- ^ "Official: Commisso buys Fiorentina". football-italia.net. 6 June 2019. Archived from the original on 16 June 2019. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- ^ "Montella confirmed as Fiorentina's head coach". SBS. 15 June 2019. Archived from the original on 1 July 2019. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- ^ "Head Coach Cesare Prandelli-returns to Fiorentina". CBS. 12 November 2020. Archived from the original on 9 November 2020. Retrieved 1 January 2021.

- ^ "Olympiakos 1-0 Fiorentina: Ayoub El Kaabi scores winner in extra-time to secure Europa Conference League title". Sky Sports. 29 May 2024. Retrieved 30 May 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Prima Squadra Maschile". ACF Fiorentina. Archived from the original on 29 October 2020. Retrieved 28 July 2021.

- ^ "Astori's number 13 shirt retired by Fiorentina and Cagliari following tragic passing". Goal.com. Archived from the original on 6 March 2018. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- ^ "geocities.com/violaequipe". Viola. Archived from the original on 27 October 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f "Fiorentina Logo History". Football Kit Archive. Archived from the original on 4 April 2024. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ a b c "ACF Fiorentina". Weltfussballarchiv.com. 24 June 2007. Archived from the original on 19 December 2012. Retrieved 10 January 2009.

- ^ a b c d fsc (13 July 2008). "Fiorentina 08/09 Lotto Home, Away, 3rd shirts - Football Shirt Culture - Latest Football Kit News and More". www.footballshirtculture.com. Archived from the original on 4 April 2024. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ "Fiorentina 1969-70 Kits". Football Kit Archive. Archived from the original on 4 April 2024. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ "Stemma Comune di Firenze". Comuni-Italiani. 24 June 2007. Archived from the original on 3 December 2007. Retrieved 27 November 2007.

- ^ a b fsc (31 July 2009). "Fiorentina 09/10 Lotto Kits - Football Shirt Culture - Latest Football Kit News and More". www.footballshirtculture.com. Retrieved 19 May 2024.

- ^ Florence, I. S. I. (27 October 2022). "Purple Pride: Connecting Florence and the U.S." ISI Florence - Study Abroad in Italy - Florence. Retrieved 19 May 2024.

- ^ "Fiorentina 1995-96 Kits". Football Kit Archive. Archived from the original on 4 April 2024. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ "First Club With 5 Player Kits – ACF Fiorentina 17–18 Home + 4 Away Kits Released". Footy Headlines. 5 July 2017. Archived from the original on 8 July 2017. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- ^ a b "ACF Fiorentina Anthem (English translation)". lyricstranslate.com. Archived from the original on 1 August 2022. Retrieved 28 July 2021.

- ^ "L'Inno". Archived from the original on 5 May 2010. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- ^ "(Ennerre) NR Nicola Raccuglia Abbigliamento Sportivo Made in Italy". NRnicolaraccuglia. 17 May 2018. Retrieved 10 July 2024.

- ^ "ABM DIFFUSION ABBIGLIAMENTO TECNICO SPORTIVO". abmdiffusion.it - abmdiffusion.it (in Italian). 27 April 2016. Retrieved 10 July 2024.

- ^ "Giochi Preziosi – Official website!". Giochi Preziosi – Official website! (in Italian). Retrieved 10 July 2024.

- ^ "Negozi di giochi e giocattoli in tutta Italia". Giocheria (in Italian). 10 June 2024. Retrieved 10 July 2024.

- ^ "Acf fiorentina and olybet announce betting partnership". acffiorentina. 30 September 2021. Archived from the original on 7 April 2023. Retrieved 30 September 2021.

- ^ During summer 2002: Serie B membership lost without playing.

- ^ a b c d e f g A.C. Fiorentina S.p.A. bilancio (financial report and accounts) on 30 June 2001 (in Italian), PDF purchased from Italian C.C.I.A.A. Archived 30 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Il Napoli sulle tracce di Gautieri L' albanese Myrtai va all' Alzano". La Gazzetta dello Sport (in Italian). 19 June 1999. Archived from the original on 26 January 2016. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ^ "Toldo e Rui Costa al Parma Buffon a un passo dalla Juve". la Repubblica (in Italian). 29 June 2001. Archived from the original on 6 October 2013. Retrieved 1 May 2013.

- ^ a b ACF Fiorentina S.p.A. bilancio (financial report and accounts) on 31 December 2005 (in Italian), PDF purchased from Italian C.C.I.A.A. Archived 30 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c ACF Fiorentina S.p.A. bilancio (financial report and accounts) on 31 December 2006 (in Italian), PDF purchased from Italian C.C.I.A.A. Archived 30 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b ACF Fiorentina S.p.A. bilancio (financial report and accounts) on 31 December 2007 (in Italian), PDF purchased from Italian C.C.I.A.A. Archived 30 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b ACF Fiorentina S.p.A. bilancio (financial report and accounts) on 31 December 2008 (in Italian), PDF purchased from Italian C.C.I.A.A. Archived 30 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b ACF Fiorentina S.p.A. bilancio (financial report and accounts) on 31 December 2009 (in Italian), PDF purchased from Italian C.C.I.A.A. Archived 30 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b ACF Fiorentina S.p.A. bilancio (financial report and accounts) on 31 December 2010 (in Italian), PDF purchased from Italian C.C.I.A.A. Archived 30 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Bilancio Fiorentina 2010: in perdita, nonostante la cessione del ramo commerciale" (in Italian). ju29ro.com. 6 September 2011. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

- ^ Marotta, Luca (7 June 2012). "Bilancio Fiorentina 2011: perdita da rendimento sportivo" (in Italian). Ju29ro.com. Archived from the original on 9 June 2012. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- ^ a b ACF Fiorentina S.p.A. bilancio (financial report and accounts) on 31 December 2011 (in Italian), PDF purchased from Italian C.C.I.A.A. Archived 30 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b ACF Fiorentina S.p.A. bilancio (financial report and accounts) on 31 December 2012 (in Italian), PDF purchased from Italian C.C.I.A.A. Archived 30 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Marotta, Luca (16 July 2013). "Bilancio Fiorentina 2012: in utile grazie a Nastasic" (in Italian). Archived from the original on 26 January 2016. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- ^ a b ACF Fiorentina S.p.A. bilancio (financial report and accounts) on 31 December 2013 (in Italian), PDF purchased from Italian C.C.I.A.A. Archived 30 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Marotta, Luca (23 July 2014). "Bilancio Fiorentina 2013: secondo utile consecutivo con plusvalenze" (in Italian). Archived from the original on 26 January 2016. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- ^ a b c ACF Fiorentina S.p.A. bilancio (financial report and accounts) on 31 December 2014 (in Italian), PDF purchased from Italian C.C.I.A.A. Archived 30 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Fiorentina joins club of teams forced to embrace austerity". il sole 24 ore. 17 September 2015. Archived from the original on 15 January 2017. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- ^ Marotta, Luca (18 July 2015). "Bilancio Fiorentina 2014: 37 milioni di perdita e l'obiettivo "imperativo" di Della Valle" (in Italian). Archived from the original on 26 January 2016. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- ^ "Financial fair play: all you need to know". UEFA. 30 June 2015. Archived from the original on 11 January 2016. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

External links

[edit]- Official website (in English and Italian)

- Team page at Goal.com

- Team page at ESPN Soccernet

- Team Page at Football-Lineups.com

- Artemio Franchi Stadium at Stadium Journey

- Fiorentina Supporters I poeti della curva

- ACF Fiorentina

- Football clubs in Italy

- Football clubs in Tuscany

- Association football clubs established in 1926

- Serie A clubs

- Serie B clubs

- Serie C clubs

- UEFA Cup Winners' Cup winning clubs

- Serie A–winning clubs

- Coppa Italia winning clubs

- 1926 establishments in Italy

- Della Valle family

- Phoenix clubs (association football)

- 2002 establishments in Italy