Hermannsburg, Northern Territory

| Ntaria (Hermannsburg) Ntaria (Western Arrarnta) Northern Territory | |

|---|---|

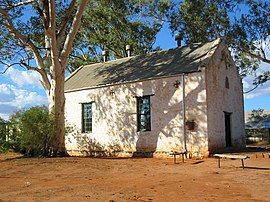

Hermannsburg Lutheran church | |

| Coordinates | 23°56′35″S 132°46′40″E / 23.94306°S 132.77778°E |

| Population | 551 (2021 census)[1] |

| Postcode(s) | 0872 |

| Location | 131 km (81 mi) from Alice Springs |

| Territory electorate(s) | Namatjira |

| Federal division(s) | Lingiari |

Hermannsburg, also known as Ntaria, is an Aboriginal community in Ljirapinta Ward of the MacDonnell Shire in the Northern Territory of Australia, 125 kilometres (78 mi); west southwest of Alice Springs, on the Finke River, in the traditional lands of the Western Arrarnta people.

Established as a Lutheran Aboriginal mission in 1877, linguist and anthropologist Carl Strehlow documented the local Western Arrernte language during his time there. The mission was known as Finke River Mission or Hermannsburg Mission, but the former term was later used to included a few more settlements, and from 2014 has applied to all Lutheran missions in Central Australia.

The land was handed over to traditional ownership in 1982 under the Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1976, and the area is now heritage-listed.

Geography

[edit]Hermannsburg lies on the Finke River within the rolling hills of the MacDonnell Ranges in the southern Central Australia region of the Northern Territory.

It is within the jurisdiction of the MacDonnell Regional Council.[2]

Demographics

[edit]At the 2011 census, Hermannsburg had a population of 625, of whom 537 (86 per cent) identified as Aboriginal.

By the 2021 census, the suburb had decreased in population to 551, of whom 491 (89.1 per cent) identified as Aboriginal.[1]

History

[edit]

19th century

[edit]Hermannsburg was established on 4 June 1877 at a sacred site known as Ntaria, which was associated with the Aranda ratapa dreaming.[3] It was conceived as an Aboriginal mission by two Lutheran missionaries, Hermann Kempe (from Dauban, near Dresden[4]) and Wilhelm F. Schwarz (from Württemberg[4]) of the Hermannsburg Mission from Germany, who had travelled overland from Bethany in the Barossa Valley in South Australia. They named their new mission among the Arrernte people after Hermannsburg in Germany where they had trained.[5][6]

They arrived with 37 horses, 20 cattle and nearly 2000 sheep,[3] five dogs and chickens. Construction began on the first building in late June 1877, made from wood and reed grass. By August a stockyard, kitchen and living quarters were also completed.[7] They had nearly no contact with Aboriginal people in the first few months, although their activities were being observed. At the end of August, a group of 15 Arrernte men visited the mission camping near the settlement. Realising that communication was difficult, the missionaries quickly learnt the local Arrernte language.[8]

A third missionary, Louis Schulze (from Saxony[4]), arrived in Adelaide in October 1877, accompanying three additional lay workers and the wives of Kempe and Schwarz. With the additional workers, five buildings were complete by December 1878. By 1880, a church was constructed with the assistance of Aboriginal labour, and the first church service took place on 12 November, followed by school on 14 November.[9] The first Aboriginal baptisms took place and in 1887 as many as 20 young people were baptised.[9]

A 54-page dictionary of 1750 words was published in 1890.[8] In 1891 the mission published an Arrernte-language book on Christian instruction and worship, containing a catechism, stories from the Bible, psalms, prayers and 53 hymns. In the same year, the Royal Society of South Australia published Schulze's thesis on the habits and customs of the local Aboriginal people and the geography of the Finke River area.[6]

While the population fluctuated, there were always about 100 people living at the mission as pastoralism increased and racial issues developed. Hostilities escalated in 1883 during a drought which saw local Aboriginal people hunt wandering stock.[7] Kempe endured trouble from the native police, who would bribe some Aboriginal men to kill their fellow tribesmen, sometimes offering them sex with the women as a reward. Kempe assisted Francis Gillen in bringing the notorious Constable Willshire to trial in Port Augusta.[10]

Fried Schwartz left the mission in 1889 due to ill health, followed by Schulze in 1891. Kempe lost his wife and child during childbirth and was himself suffering from typhoid, so also left the mission in 1891.[citation needed] In this way the first term of administration of the mission ended.[10][11]

The settlement was continued by lay workers until Pastor Carl Strehlow arrived in October 1894[12] (or 1895?) with his wife, Frieda Strehlow (née Kaysser). Frieda was born in 1875, and had met Strehlow when he was training to be a missionary in 1892. After marrying in Adelaide, the couple travelled by horse and buggy to Hermannsburg. Many of the locals could by this time speak German,[10] and Pastor Strehlow continued documenting the local language, and was involved with local people in Bible translation and hymn writing. In 1896 additional construction took place of a school house, which was also used as a chapel and an eating house.[citation needed] Frieda taught the women about a healthy diet and how to reduce child mortality.[10] Severe droughts during 1897-8 and again in 1903 meant poor food production and an influx of Aboriginal people.[7]

20th century

[edit]

In mid-1910, the Strehlows left on a break to Germany and placed their five eldest children with relatives and friends there, in order to secure a good education for them.[12] While they were away, they were replaced by Leibler and then by teacher H. H. Heinrich.[7] Carl, Frieda, and their son Theo (Ted Strehlow), returned in 1912,[12] having received letters from Aranda elders imploring them to return.[10]

Many English-speaking people in the area mistrusted the German missionaries, and did not have a high opinion of the Aboriginal people.[10] From 1912 to 1922, Baldwin Spencer, then Special Commissioner and Chief Protector of Aborigines, attempted to shut down the mission. In his 1913 report, Spencer proposed taking all Aboriginal children away from their parents and setting up reserves where the children would be denied any contact with their parents, be prevented from speaking their languages and made incapable of living in the bush.[13] He was particularly keen to make sure that "half-caste" children had no contact with camp life. Hermannsburg was to be taken away from the Lutherans and "serve as a reserve for the remnants of the southern central tribes where they can, under proper and competent control, be trained to habits of industry".[14] However, when the Administrator of the Northern Territory, John A. Gilruth, came down from Darwin in 1913 to see whether these negative reports were true, he gave Strehlow his support.[10]

The Strehlows finally left on 22 October 1922 when Pastor Strehlow contracted dropsy. He died the next day at Horseshoe Bend.[7]

The mission was without a missionary until Pastor Johannes Riedel arrived in late 1923, followed by Pastor Friedrich Wilhelm Albrecht on 19 April 1926 with his wife. They stayed until 1962. Drought struck again in 1927 causing ill heath and scurvy. There was yet another influx of Aboriginal people and 85 per cent of Aboriginal children died during this time. A delivery of oranges was considered "a miracle".[9]

Albrecht was integral to the development of the Kuprilya Springs Pipeline, which piped water from a permanent water hole 6 km (3.7 mi) to the mission. It was funded in part by Melbourne artist Violet Teague and her sister Una, and was completed on 1 October 1935.[15] Albrecht also developed various other enterprises such as a large vegetable garden and orchard, beef cattle ranching and a tannery. They also supported the development of the school of watercolour landscape artists, which became one of the special heritages of the Hermannsburg area.[7]

The first two Aboriginal pastors were ordained in 1964, Conrad Rabaraba and Cyril Motna.[6] Doug Radke was pastor from 1965 to 1969.[16]

The mission land was handed over to traditional ownership in 1982 under the Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1976.[17]

The settlement and its satellite communities were funded as an outstation during the 1980s.[18]

21st century

[edit]By 2014, there were 24 Aboriginal pastors, and more than 40 trainees and female church leaders. The congregation included around 6,000 people, and sermons were being delivered in Luritja, Western Arrarnta, Pitjantjatjara, Anmatyerre, and Alyawarr, as well as English.[19]

Legacy of the missionaries

[edit]The Lutherans worked at keeping the local languages alive, and the Strehlows greatly increased the knowledge of Aranda culture. Much is preserved in the Strehlow Research Centre in Alice Springs, and author John Strehlow, son of Ted, has written a two-volume book about his grandparents, Carl and Frieda Strehlow.[10]

According to musician Warren H Williams, who was born at Hermannsburg, "If the missionaries had not come to Hermannsburg, there would be no blackfellas in Central Australia" – this observation based on the attitude of the English-speaking administrators and other settlers in the region.[10]

Heritage listing

[edit]The Hermannsburg Historic Precinct was listed on the Northern Territory Heritage Register on 19 May 2001 and on the Australian National Heritage List in April 2006.[17][20]

The mission buildings, located adjacent to the town of Ntaria, are empty. The heritage precinct is owned by the local Western Arrarnta people, represented by the Hermannsburg Historical Society, while the Finke River Mission (a term that now embraces all Lutheran missionary activities in the Northern Territory[21]) act as managers.[19]

Facilities

[edit]The Finke River Mission operates the general store, by request of the community.[19]

Art

[edit]

Albert Namatjira (1902–1959), famous for his watercolour landscapes, founded a style later known as the Hermannsburg School of painting.

The Hermannsburg Potters are well known for their ceramic art,[22] and many successful artists live in the town.[23]

Choir

[edit]In 1891 Pastors Kempe and Schwarze created a Western Arrernte language version of the Lutheran hymn book, comprising 53 hymns.[6] The congregation learnt to sing them, and a choir was born. Singing was an important part of the church activities, and there were many versions of the choir over the years, eventually evolving into what is as of 2022[update] called the Ntaria Choir.[24] The choir sings in Western Arrernte and Pitjantjatjara. Initially a mixed choir, it became women-only in the 1970s until the late 2010s, when men joined the choir again. It is today world-famous and has produced several albums.[25] As of 2020[update] it included six women and two men.[24]

"Finke River Mission"

[edit]"Finke River Mission" was initially an alternative name for the Hermannsburg Mission, but this name was later often used to include the newer government settlements at Haasts Bluff, Areyonga and Papunya. In 2014, the Lutheran Church of Australia started using the term to apply retrospectively to all Lutheran missionary activity in Central Australia since the first mission was established at Hermannsburg in 1877, including establishments at Alice Springs, and the name continues to be used as of 2022[update].[21][6][26]

Yirara College is a co-educational boarding school in Alice Springs run by Finke River Mission, catering for around 200 Aboriginal students. It also has a small campus in Kintore[19] (Walungurru), catering for around 30 students.[27]

As of 2015, there were 21 Aboriginal pastors and many other church workers employed by Finke River Mission, serving over 30 communities in five Aboriginal languages.[6]

Notable people

[edit]The Radkes

[edit]Reverend Doug Radke and his wife Olga Radke OAM, along with their four children, moved to the Finke River Mission in 1965. Both worked with the Aboriginal community until 1969. They both loved music, and worked with the choir, including taking the singers on a tour to the southern states in 1967, for which Olga was the piano accompanist and organist. After leaving Hermannsburg they moved on to work with other Lutheran congregations, until Doug's untimely death, when Olga moved to Alice Springs to work at the Strehlow Research Centre as a volunteer. In 2003, she became a member of the Prisoners' Aid and Rehabilitation Association of Alice Springs. She lobbied for a support group for people with mental illness, and has continued to work with churches and choirs. In the 2015 Queen's Birthday honours list, Olga was awarded the Medal of the Order of Australia for service to the community of Alice Springs.[16][28] In 2021, she wrote and published a book about the 1967 tour, entitled Hermannsburg Choir on Tour - Remembering the 1967 Choir Tour. The book includes her original detailed "Choir Tour Diary".[29][16]

Other people

[edit]- Yvette Holt, a poet from Brisbane, has lived in Hermannsburg since 2009 (as of 2021[update])[30]

- Peter Latz (1941–), botanist, grew up there

- Shane Nicholson, after a visit to Hermannsburg with Warren H Williams, wrote a song called "Hermannsburg" in 2015

- Otto Pareroultja, first painter in the region to paint in a more impressionist style[31][32]

- Ted Strehlow (1908–1978), son of Carl, noted anthropologist, initiated into Aranda customs

- Gus Williams, Aboriginal country music singer

- Warren H Williams, son of Gus, also a singer, and a traditional owner of Ntaria

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Australian Bureau of Statistics (28 June 2022). "2021 Community Profiles: Hermannsburg (Suburb)". 2021 Census of Population and Housing. Retrieved 17 May 2024.

- ^ "Hermannsburg". MacDonnell Regional Council.

- ^ a b Kenny, Anna (20 December 2013). The Aranda's Pepa: An introduction to Carl Strehlow's Masterpiece Die Aranda- und Loritja-Stämme in Zentral-Australien (1907-1920). ANU Press. doi:10.22459/ap.12.2013. ISBN 978-1-921536-77-9. PDF p.15+

- ^ a b c Nutting, Dave. "Hermannsburg Lutheran Mission". German Australia. Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- ^ Scherer, P.A. (1995). The Hermannsburg chronicle, 1877-1933. Tanunda, S.A.: P.A. Scherer. ISBN 0646247921.

- ^ a b c d e f "Finke River Mission 135th Anniversary". Lutheran Church of Australia. Archived from the original on 24 June 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f Watson, Penny (1987). "Early Missionaries of Hermannsburg". Heritage Australia. 6 (2): 31–34.

- ^ a b Strehlow Research Centre. Alice Springs, N.T.: Strehlow Research Centre. 1993. ISBN 0724528210.

- ^ a b c M. Lohe; F.W. Albrecht; L.H. Leske (1977). Everard Leske (ed.). Hermannsburg: a vision and a mission. Adelaide: Lutheran Pub. House. ISBN 0859100448.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Egan, Ted (23 December 2019). "Hermannsburg Mission: questions of survival". Alice Springs News. Speech by former Administrator Ted Egan AO at the launch of Volume II of The Tale of Frieda Kaysser by John Strehlow. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ "History". Finke River Mission. 19 October 2018. Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- ^ a b c "Strehlow, Rev. Carl (1871-1922)". German Missionaries in Australia. Griffith University. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ Spencer, Walter Baldwin; Australia. Department of External Affairs (1913), Preliminary report on the Aboriginals of the Northern Territory, Bulletin of the Northern Territory, no. 7, Dept. of External Affairs, p. 23, retrieved 11 November 2022

- ^ Spencer, Walter Baldwin; Australia. Department of External Affairs (1913), Preliminary report on the Aboriginals of the Northern Territory, Bulletin of the Northern Territory, no. 7, Dept. of External Affairs, p. 20a, retrieved 11 November 2022

- ^ Petrick, Jose (2007). Kuprilya Springs: Hermannsburg & other things. Alice Springs, N.T.: Jose Petrick. ISBN 9780646478104.

- ^ a b c Radke, Olga (2021). Hermannsburg Choir on Tour - Remembering the 1967 Choir Tour; Including the Original 'Choir Tour Diary'. Friends of the Strehlow Research Centre. ISBN 978-0-6485919-2-4. Retrieved 10 November 2022.

- ^ a b "Hermannsburg Historic Village Precinct". Heritage Register. Northern Territory Government. Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- ^ Parliament of Australia. House of Representatives Standing Committee on Aboriginal Affairs; Blanchard, Allen (March 1987). Inquiry into the Aboriginal homelands movement in Australia. Australian Government Publishing Service. ISBN 0-644-06201-0. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

Published online 12 June 2011

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) PDF - ^ a b c d "Hermannsburg Historic Precinct and Finke River Mission Today". Hermannsburg Historic Precinct. Retrieved 10 November 2022.

- ^ "Australian National Heritage listing for the Hermannsburg Historic Precinct". Environment.gov.au. Archived from the original on 25 October 2012. Retrieved 25 December 2012.

- ^ a b George, Karen; George, Gary (17 March 2017). "Finke River Mission - Glossary Term - Northern Territory". Find & Connect. Retrieved 8 November 2022.

- ^ "Hermannsburg Potters: Aranda Artists of Central Australia". Hermannsburg Potters. 19 September 2022. Retrieved 8 November 2022.

- ^ "Local artists". Hermannsburg Historic Precinct. Retrieved 8 November 2022.

- ^ a b "The Hermannsburg Choir". Hermannsburg Historic Precinct. Retrieved 8 November 2022.

- ^ Strahle, Graham (29 May 2019). "Indigenous Women's Only Ntaria Choir Reaches Back To Bach". Music Australia. Retrieved 8 November 2022.

- ^ "About". Finke River Mission. 29 October 2018. Retrieved 8 November 2022.

- ^ "Kintore Campus (Walungurru)". Yirara College. Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- ^ "Mrs Olga Josephine RADKE: Medal of the Order of Australia". Australian Honours Search Facility. Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (Australia). Retrieved 10 November 2022.

- ^ Barwick, Rohan (16 July 2021). "Historic Hermannsburg Choir tour celebrated in new book" (audio, 30 mins). ABC Darwin. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 10 November 2022.

- ^ "Yvette Holt". AustLit. University of Queensland. 9 August 2019. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- ^ Kamholtz, Damien; Namatjira, Lenie (2006). Albert : Albert Namatjira and the Hermannsburg Watercolour Artists. Adelaide: Openbook Australia. ISBN 9780646467399. OCLC 224953943.

- ^ "Otto Pareroultja". Aboriginal Bark Paintings. 6 February 2018. Retrieved 8 August 2019.

Further reading

[edit]- Hermannsburg Aboriginal Mission, Ntaria South Australian History - Flinders Ranges Research

- Krichauff, F. E. H. W. (26 January 1886). "The Finke River Mission Station". South Australian Register. Vol. LI, no. 12, 231. p. 7 – via National Library of Australia. Detailed report compiled in 1885 from data supplied by Kempe and a letter by Schwarz.

- Roennfeldt, D. and the community members (2006) Western Arrarnta Picture Dictionary. IAD Press, Northern Territory, Australia. ISBN 1 86465 069 9.

- Strehlow, T. G. H. (1969). Journey to Horseshoe Bend (PDF). Angus and Robertson.

External links

[edit]- "Hermannsburg". MacDonnell Council.

- "Albert Namatjira: Mt Hermannsburg, Finke River". National Gallery of Australia. Painting by Namatjira of the mountain

- Photograph of Hermannsburg in 1994 National Library of Australia

- Hermannsburg Potters