Cthulhu

| Cthulhu | |

|---|---|

| Cthulhu Mythos character | |

Sketch of Cthulhu drawn by Lovecraft (11 May 1934) | |

| First appearance | "The Call of Cthulhu" (1928) |

| Created by | H. P. Lovecraft |

| In-universe information | |

| Species | Great Old One |

| Gender | Variable depending on the publisher's ideas |

| Family |

|

Cthulhu is a fictional cosmic entity created by writer H. P. Lovecraft. It was introduced in his short story "The Call of Cthulhu",[2] published by the American pulp magazine Weird Tales in 1928. Considered a Great Old One within the pantheon of Lovecraftian cosmic entities, this creature has since been featured in numerous pop culture references. Lovecraft depicts it as a gigantic entity worshipped by cultists, in the shape of a green octopus, dragon, and a caricature of human form. It is the namesake of the Lovecraft-inspired Cthulhu Mythos.

Etymology, spelling, and pronunciation

[edit]Invented by Lovecraft in 1928, the name Cthulhu was probably chosen to echo the word chthonic (Ancient Greek "of the earth"), as apparently suggested by Lovecraft himself at the end of his 1923 tale "The Rats in the Walls".[3] The chthonic, or earth-dwelling, spirit has precedents in numerous ancient and medieval mythologies, often guarding mines and precious underground treasures, notably in the Germanic dwarfs and the Greek Chalybes, Telchines, or Dactyls.[4]

Lovecraft transcribed the pronunciation of Cthulhu as Khlûl′-hloo, and said, "the first syllable pronounced gutturally and very thickly. The 'u' is about like that in 'full', and the first syllable is not unlike 'klul' in sound, hence the 'h' represents the guttural thickness"[5] yielding something akin to /ˈq(χ)lʊlˌhluː/.[original research?] S. T. Joshi points out, however, that Lovecraft gave different pronunciations on different occasions.[6] According to Lovecraft, this is merely the closest that the human vocal apparatus can come to reproducing the syllables of an alien language.[7] Cthulhu has also been spelled in many other ways, including Tulu, Katulu, and Kutulu.[8]

Long after Lovecraft's death, Chaosium stated in the Call of Cthulhu role-playing game: "we say it kuh-THOOL-hu" (/kəˈθuːluː/), even while noting that Lovecraft said it differently.[9] Others use the pronunciation /kəˈtuːluː/.[10]

Description

[edit]In "The Call of Cthulhu", H. P. Lovecraft describes a statue of Cthulhu as: "A monster of vaguely anthropoid outline, but with an octopus-like head whose face was a mass of feelers, a scaly, rubbery-looking body, prodigious claws on hind and fore feet, and long, narrow wings behind."[11] A carving of Cthulhu is described thusly: "It seemed to be a sort of monster, or symbol representing a monster, of a form which only a diseased fancy could conceive. If I say that my somewhat extravagant imagination yielded simultaneous pictures of an octopus, a dragon, and a human caricature, I shall not be unfaithful to the spirit of the thing. A pulpy, tentacled head surmounted a grotesque and scaly body with rudimentary wings."[11]

Johansen in The Call of Cthulhu states that "The Thing cannot be described—there is no language for such abysms of shrieking and immemorial lunacy, such eldritch contradictions of all matter, force, and cosmic order. A mountain walked or stumbled." Cthulhu is described again shortly thereafter as a "mountainous monstrosity". His age is described to be at least "vigintillions of years".[12] He is also said to have cast spells which preserved the Great Old Ones until their reawakening.

Cthulhu is said to resemble a green octopus, dragon, and a human caricature, hundreds of meters tall, with webbed, human-looking arms and legs and a pair of rudimentary wings on its back.[11] Its head is depicted as similar to the entirety of a gigantic octopus, with an unknown number of tentacles surrounding its supposed mouth.

Publication history

[edit]The short story that first mentions Cthulhu, "The Call of Cthulhu", was published in Weird Tales in 1928, and established the character as a malevolent entity, hibernating within R'lyeh, an underwater city in the South Pacific. The imprisoned Cthulhu is apparently the source of constant subconscious anxiety for all mankind, and is also the object of worship, both by many human cults (including some within New Zealand, Greenland, Louisiana, and the Chinese mountains) and by other Lovecraftian monsters (called Deep Ones[13] and Mi-Go[14]). The short story asserts the premise that, while currently trapped, Cthulhu will eventually return. His worshippers chant "Ph'nglui mglw'nafh Cthulhu R'lyeh wgah'nagl fhtagn" ("In his house at R'lyeh, dead Cthulhu waits dreaming").[11]

Lovecraft conceived a detailed genealogy for Cthulhu (published as "Letter 617" in Selected Letters)[1] and made the character a central reference in his works.[15] The short story "The Dunwich Horror" (1928)[16] refers to Cthulhu, while "The Whisperer in Darkness" (1930) hints that one of his characters knows the creature's origins ("I learned whence Cthulhu first came, and why half the great temporary stars of history had flared forth.")[14] The 1931 novella At the Mountains of Madness refers to the "star-spawn of Cthulhu", who warred with another race called the Elder Things before the dawn of man.[17]

August Derleth, a correspondent of Lovecraft's, used the creature's name to identify the system of lore employed by Lovecraft and his literary successors, the Cthulhu Mythos. In 1937, Derleth wrote the short story "The Return of Hastur", and proposed two groups of opposed cosmic entities:

the Old or Ancient Ones, the Elder Gods, of cosmic good, and those of cosmic evil, bearing many names, and themselves of different groups, as if associated with the elements and yet transcending them: for there are the Water Beings, hidden in the depths; those of Air that are the primal lurkers beyond time; those of Earth, horrible animate survivors of distant eons.[18]: 256

According to Derleth's scheme, "Great Cthulhu is one of the Water Elementals" and was engaged in an age-old arch-rivalry with a designated air elemental, Hastur the Unspeakable, described as Cthulhu's "half-brother."[18]: 256, 266 Based on this framework, Derleth wrote a series of short stories published in Weird Tales (1944–1952) and collected as The Trail of Cthulhu, depicting the struggle of a Dr. Laban Shrewsbury and his associates against Cthulhu and his minions. In addition, Cthulhu is referenced in Derleth's 1945 novel The Lurker at the Threshold published by Arkham House. The novel can also be found in The Watchers Out of Time and Others, a collection of stories from Derleth's interpretations of Lovecraftian Mythos published by Arkham House in 1974.

Derleth's interpretations have been criticized by Lovecraft enthusiast Michel Houellebecq, among others. Houellebecq's H. P. Lovecraft: Against the World, Against Life (2005) decries Derleth for attempting to reshape Lovecraft's strictly amoral continuity into a stereotypical conflict between forces of objective good and evil.[19]

In John Glasby's "A Shadow from the Aeons", Cthulhu is seen by the narrator roaming the riverbank near Dominic Waldron's castle, and roaring.[20]

The character's influence also extended into gaming literature; games company TSR included an entire chapter on the Cthulhu mythos (including character statistics) in the first printing of Dungeons & Dragons sourcebook Deities & Demigods (1980). TSR, however, were unaware that Arkham House, which asserted copyright on almost all Lovecraft literature, had already licensed the Cthulhu property to game company Chaosium. Although Chaosium stipulated that TSR could continue to use the material if each future edition featured a published credit to Chaosium, TSR refused and the material was removed from all subsequent editions.[21]

Influence

[edit]Politics

[edit]

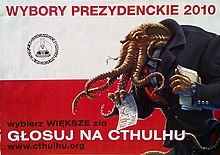

Cthulhu has appeared as a parody candidate in several elections, including the 2010 Polish presidential election and the 2012 and 2016 US presidential elections.[22][23] The faux campaigns usually satirize voters who claim to vote for the "lesser evil". "Cthulhu for America" ran during the 2016 American presidential election, drawing comparisons with other satirical presidential candidates such as Vermin Supreme.[24] The organization had a platform that included the legalization of human sacrifice, driving all Americans insane, and an end to peace.[25]

In 2016, the troll account known as "The Dark Lord Cthulhu" submitted an official application to be on the Massachusetts Presidential Ballot. The account also raised over $4000 from fans to fund the campaign through a gofundme.com page. Gofundme removed the campaign page and refunded contributions.[citation needed]

Science

[edit]Several organisms have been named after Cthulhu, including the California spider Pimoa cthulhu,[26] the New Guinea moth Speiredonia cthulhui,[27] and Sollasina cthulhu, a fossil echinoderm.[28] Two microorganisms that assist in the digestion of wood by termites have been named after Cthulhu and Cthulhu's "daughter" Cthylla: Cthulhu macrofasciculumque and Cthylla microfasciculumque.[29]

In 2014, science and technology scholar Donna Haraway gave a talk entitled "Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Chthulucene: Staying with the Trouble", in which she proposed the term "Chthulucene" as an alternative for the concept of the Anthropocene era, due to the entangling interconnectedness of all supposedly individual beings.[30] Haraway has denied any indebtedness to Lovecraft's Cthulhu, claiming that her "chthulu" is derived from Greek khthonios, "of the earth".[31] However, the Lovecraft character is much closer to her coined term than the Greek root, and her description of its meaning coincides with Lovecraft's idea of the apocalyptic, multitentacled threat of Cthulhu to collapse civilization into an endless dark horror: "Chthulucene does not close in on itself; it does not round off; its contact zones are ubiquitous and continuously spin out loopy tendrils."[32]

In 2015, an elongated, dark region along the equator of Pluto, initially referred to as "the Whale", was proposed to be named "Cthulhu Region", by the NASA team responsible for the New Horizons mission.[33] It was given the informal name Cthulhu Macula,[34][35] though the feature was later officially named Belton Regio by the International Astronomical Union.[36]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Lovecraft, H. P. (1967). Selected Letters (1932–1934). Sauk City, Wisconsin: Arkham House. Letter 617. ISBN 0-87054-035-1. Retrieved 17 August 2023.

- ^ "{title}". Archived from the original on 2018-08-02. Retrieved 2018-08-02.

- ^ Callaghan, Gavin (2013). H. P. Lovecraft's Dark Arcadia: The Satire, Symbology and Contradiction. McFarland. p. 192. ISBN 978-1476602394.

- ^ Kearns, Emily (2011). Finkelberg, Margalit (ed.). "Chthonic deities". The Homer encyclopedia. Wiley. Retrieved 4 May 2017.

- ^ Lovecraft, H. P. Selected Letters V. pp. 10–11.

- ^ Joshi, S. T. "The Call of Cthulhu". The Call of Cthulhu and Other Weird Stories. note 9.

- ^ "Cthul-Who?: How Do You Pronounce 'Cthulhu'?", Crypt of Cthulhu #9

- ^ Harms, Thomas. "Cthulhu" and "PanCthulhu". The Encyclopedia Cthulhiana. p. 64.

- ^ Petersen, Sandy; Willis, Lynn; Herber, Keith (1981). Call of Cthulhu (2 ed.). Oakland, California: Chaosium.:What's in this box?

- ^ e.g. the video game Call of Cthulhu[1] Archived 2020-09-01 at the Wayback Machine and season 14 of South Park.

- ^ a b c d s:The Call of Cthulhu

- ^ ""The Call of Cthulhu" by H. P. Lovecraft". www.hplovecraft.com. Retrieved 2024-12-13.

- ^ s:The Shadow Over Innsmouth

- ^ a b s:The Whisperer in Darkness

- ^ Angell, George Gammell (1982). Price, Robert M. (ed.). "Cthulhu Elsewhere in Lovecraft". Crypt of Cthulhu (9): 13–15. ISSN 1077-8179.

- ^ s:The Dunwich Horror

- ^ Lovecraft, H. P. At the Mountains of Madness. p. 66. Archived from the original on 2011-06-06. Retrieved 2011-04-14.

- ^ a b Derleth, August. "The Return of Hastur". In Price, Robert M. (ed.). The Hastur Cycle.

- ^ Bloch, Robert. "Heritage of Horror". The Best of H. P. Lovecraft: Bloodcurdling Tales of Horror and the Macabre.

- ^ Glasby, John S. (2015-08-09). The Brooding City and Other Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos. Ramble House.

- ^ "Deities & Demigods, Legends & Lore". The Acaeum. Archived from the original on 2010-09-03. Retrieved 2010-05-10.

- ^ "Cthulhu for America". Archived from the original on 3 August 2016. Retrieved 3 Aug 2016.

- ^ "Cthulhu Dagon 2012". Archived from the original on 2016-10-14. Retrieved 2016-10-29.

- ^ Watson, Zebbie (June 16, 2016). "Who Is Behind Cthulhu For America?". Inverse. Archived from the original on October 25, 2020. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- ^ Barnett, David (March 1, 2016). "Could Cthulhu trump the other Super Tuesday contenders?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on June 13, 2020. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- ^ Hormiga, G. (1994). "A revision and cladistic analysis of the spider family Pimoidae (Araneoidea: Araneae)" (PDF). Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology. 549 (549): 1–104. doi:10.5479/si.00810282.549. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-10-13. Retrieved 2011-05-09.

- ^ Zilli, Alberto; Holloway, Jeremy D. & Hogenes, Willem (2005). "An Overview of the Genus Speiredonia with Description of Seven New Species (Insecta, Lepidoptera: Noctuidae)". Aldrovandia. 1: 17–36. Archived from the original on 2011-07-22 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Rahman, Imran A.; Thompson, Jeffrey R.; Briggs, Derek E. G.; Siveter, David J.; Siveter, Derek J.; Sutton, Mark D. (2019). "A new ophiocistioid with soft-tissue preservation from the Silurian Herefordshire Lagerstätte, and the evolution of the holothurian body plan" (PDF). Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 286 (1900): 20182792. doi:10.1098/rspb.2018.2792. PMC 6501687. PMID 30966985. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-09-23. Retrieved 2019-09-23.

- ^ James, Erick R.; Okamoto, Noriko; Burki, Fabien; Scheffrahn, Rudolf H.; Keeling, Patrick J. (2013-03-18). Badger, Jonathan H. (ed.). "Cthulhu Macrofasciculumque n. g., n. sp. and Cthylla Microfasciculumque n. g., n. sp., a Newly Identified Lineage of Parabasalian Termite Symbionts". PLOS ONE. 8 (3): e58509. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...858509J. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0058509. PMC 3601090. PMID 23526991.

- ^ Donna Haraway (9 May 2014). Donna Haraway, "Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Chthulucene: Staying with the Trouble", 5/9/14. Vimeo, Inc. Archived from the original on 28 January 2017. Retrieved 2017-03-06.

- ^ Haraway, Donna (2016). Staying with the Trouble. Durham and London: Duke University Press. pp. 174n4. ISBN 978-0-8223-6224-1.

- ^ Wark, McKenzie (September 8, 2016). "Chthulucene, Capitalocene, Anthropocene". PublicSeminar.org. Archived from the original on 2017-12-01. Retrieved 2017-11-30.

- ^ Feltman, Rachel (14 July 2015). "New data reveals that Pluto's heart is broken". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2015-07-15. Retrieved 14 July 2015.

- ^ Amanda M. Zangari; et al. (November 2015). "New Horizons disk-integrated approach photometry of Pluto and Charon". AAS/Division for Planetary Sciences Meeting Abstracts #47. 47. American Astronomical Society, DPS meeting #47, id.210.01: 210.01. Bibcode:2015DPS....4721001Z.

- ^ Stern, S. A.; Grundy, W.; McKinnon, W. B.; Weaver, H. A.; Young, L. A. (2018). "The Pluto System After New Horizons". Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. 56: 357–392. arXiv:1712.05669. Bibcode:2018ARA&A..56..357S. doi:10.1146/annurev-astro-081817-051935. S2CID 119072504.

- ^ "Two Names Approved for Pluto: Belton Regio and Safronov Regio | USGS Astrogeology Science Center". astrogeology.usgs.gov. Retrieved 2023-09-27.

Further reading

[edit]- Bloch, Robert (1982). "Heritage of Horror". The Best of H. P. Lovecraft: Bloodcurdling Tales of Horror and the Macabre (1st ed.). Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-35080-4.

- Burleson, Donald R. (1983). H. P. Lovecraft, A Critical Study. Westport, CT / London, England: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-23255-5.

- Burnett, Cathy (1996). Spectrum No. 3:The Best in Contemporary Fantastic Art. Nevada City, CA, 95959 USA: Underwood Books. ISBN 1-887424-10-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Harms, Daniel (1998). "Cthulhu". The Encyclopedia Cthulhiana (2nd ed.). Oakland, CA: Chaosium. pp. 64–7. ISBN 1568821190.

- "Idh-yaa", p. 148. Ibid.

- "Star-spawn of Cthulhu", pp. 283 – 4. Ibid.

- Joshi, S. T.; Schultz, David E. (2001). An H. P. Lovecraft Encyclopedia. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0313315787.

- Lovecraft, Howard P. (1999) [1928]. "The Call of Cthulhu". In S. T. Joshi (ed.). The Call of Cthulhu and Other Weird Stories. London, UK; New York, NY: Penguin Books. Archived from the original on November 26, 2009.

- Lovecraft, Howard P. (1968). Selected Letters II. Sauk City, WI: Arkham House. ISBN 0870540297.

- Lovecraft, Howard P. (1976). Selected Letters V. Sauk City, WI: Arkham House. ISBN 087054036X.

- Marsh, Philip. R'lyehian as a Toy Language – on psycholinguistics. Lehigh Acres, FL 33970-0085 USA: Philip Marsh.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Mosig, Yozan Dirk W. (1997). Mosig at Last: A Psychologist Looks at H. P. Lovecraft (1st ed.). West Warwick, RI: Necronomicon Press. ISBN 0940884909.

- Pearsall, Anthony B. (2005). The Lovecraft Lexicon (1st ed.). Tempe, AZ: New Falcon Pub. ISBN 1561841293.

- "Other Lovecraftian Products" Archived 2008-07-23 at the Wayback Machine, The H.P. Lovecraft Archive

External links

[edit]- Lovecraft, H. P. "The Call of Cthulhu". www.hplovecraft.com. Donovan K. Loucks. Retrieved 2020-04-15.

- Cthulhu Mythos deities

- Extraterrestrial supervillains

- Fictional aquatic aliens

- Fictional cephalopods

- Fictional demons

- Fictional gods

- Fictional immortals

- Fictional priests and priestesses

- Fictional sea monsters

- Fictional telepaths

- Horror villains

- Literary characters introduced in 1928

- Literary villains

- New religious movement deities

- H. P. Lovecraft characters