Fauvism

Fauvism (/foʊvɪzəm/ FOH-viz-əm) is a style of painting and an art movement that emerged in France at the beginning of the 20th century. It was the style of les Fauves (French pronunciation: [le fov], the wild beasts), a group of modern artists whose works emphasized painterly qualities and strong colour over the representational or realistic values retained by Impressionism. While Fauvism as a style began around 1904 and continued beyond 1910, the movement as such lasted only a few years, 1905–1908, and had three exhibitions.[1][2] The leaders of the movement were André Derain and Henri Matisse.

Artists and style

[edit]Besides Matisse and Derain, other artists included Robert Deborne, Albert Marquet, Charles Camoin, Bela Czobel, Louis Valtat, Jean Puy, Maurice de Vlaminck, Henri Manguin, Raoul Dufy, Othon Friesz, Adolphe Wansart, Georges Rouault, Jean Metzinger, Kees van Dongen, Émilie Charmy and Georges Braque (subsequently Picasso's partner in Cubism).[1]

The paintings of the Fauves were characterized by seemingly wild brush work and strident colors, while their subject matter had a high degree of simplification and abstraction.[3] Fauvism can be classified as an extreme development of Van Gogh's Post-Impressionism fused with the pointillism of Seurat[3] and other Neo-Impressionist painters, in particular Paul Signac. Other key influences were Paul Cézanne[4] and Paul Gauguin, whose employment of areas of saturated color—notably in paintings from Tahiti—strongly influenced Derain's work at Collioure in 1905.[5] In 1888, Gauguin had said to Paul Sérusier:[6] "How do you see these trees? They are yellow. So, put in yellow; this shadow, rather blue, paint it with pure ultramarine; these red leaves? Put in vermilion." Fauvism has been compared to Expressionism, both in its use of pure color and unconstrained brushwork.[3] Some of the Fauves were among the first avant-garde artists to collect and study African and Oceanic art, alongside other forms of non-Western and folk art, leading several Fauves toward the development of Cubism.[7]

Origins

[edit]

Gustave Moreau was the movement's inspirational teacher;[8] a controversial professor at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris and a Symbolist painter, he taught Matisse, Marquet, Manguin, Rouault, and Camoin during the 1890s, and was viewed by critics as the group's philosophical leader until Matisse was recognized as such in 1904.[8] Moreau's broad-mindedness, originality and affirmation of the expressive potency of pure color was inspirational for his students.[9] Matisse said of him, "He did not set us on the right roads, but off the roads. He disturbed our complacency."[9] This source of empathy was taken away with Moreau's death in 1898, but the artists discovered other catalysts for their development.[9]

In 1896, Matisse, then an unknown art student, visited the artist John Russell on the island of Belle Île off the coast of Brittany.[10] Russell was an Impressionist painter; Matisse had never previously seen an Impressionist work directly, and was so shocked at the style that he left after ten days, saying, "I couldn't stand it any more."[10] The next year he returned as Russell's student and abandoned his earth-colored palette for bright Impressionist colors, later stating, "Russell was my teacher, and Russell explained color theory to me."[10] Russell had been a close friend of Vincent van Gogh and gave Matisse a Van Gogh drawing.[10]

In 1901, Maurice de Vlaminck encountered the work of Van Gogh for the first time at an exhibition, declaring soon after that he loved Van Gogh more than his own father; he started to work by squeezing paint directly onto the canvas from the tube.[9] In parallel with the artists' discovery of contemporary avant-garde art came an appreciation of pre-Renaissance French art, which was shown in a 1904 exhibition, French Primitives.[9] Another aesthetic influence was African sculpture, of which Vlaminck, Derain and Matisse were early collectors.[9]

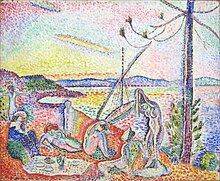

Many of the Fauve characteristics first cohered in Matisse's painting, Luxe, Calme et Volupté ("Luxury, Calm and Pleasure"), which he painted in the summer of 1904, while he was in Saint-Tropez with Paul Signac and Henri-Edmond Cross.[9]

Salon d’Automne 1905

[edit]

After viewing the boldly colored canvases of Henri Matisse, André Derain, Albert Marquet, Maurice de Vlaminck, Kees van Dongen, Charles Camoin, Robert Deborne and Jean Puy at the Salon d'Automne of 1905,[12] the critic Louis Vauxcelles disparaged the painters as "fauves" (wild beasts), thus giving their movement the name by which it became known, Fauvism. The artists shared their first exhibition at the 1905 Salon d’Automne. The group gained their name after Vauxcelles described their show of work with the phrase "Donatello chez les fauves" ("Donatello among the wild beasts"), contrasting their "orgy of pure tones" with a Renaissance-style sculpture by Albert Marque that shared the room with them.[13][14]

Henri Rousseau was not a Fauve, but his large jungle scene The Hungry Lion Throws Itself on the Antelope was exhibited near Matisse's work and may have had an influence on the pejorative used.[15] Vauxcelles' comment was printed on 17 October 1905 in Gil Blas,[13] a daily newspaper, and passed into popular usage.[14][16] The pictures gained considerable condemnation—"A pot of paint has been flung in the face of the public", wrote the critic Camille Mauclair (1872–1945)—but also some favorable attention.[14] The painting that was singled out for attacks was Matisse's Woman with a Hat; this work's purchase by Gertrude and Leo Stein had a very positive effect on Matisse, who was suffering demoralization from the bad reception of his work.[14] Matisse's Neo-Impressionist landscape, Luxe, Calme et Volupté, had already been exhibited at the Salon des Indépendants in the spring of 1905.[17]

Salon des Indépendants 1906

[edit]

Following the Salon d'Automne of 1905, which marked the beginning of Fauvism, the Salon des Indépendants of 1906 marked the first time all the Fauves would exhibit together. The centerpiece of the exhibition was Matisse's monumental Le Bonheur de Vivre (The Joy of Life).[18] Critics were horrified by its flatness, bright colors, eclectic style and mixed technique.[18] The triangular composition is closely related to Paul Cézanne's Bathers, a series that would soon become a source of inspiration for Picasso's Les Demoiselles d'Avignon.[19][20]

The elected members of the hanging committee included Matisse, Signac and Metzinger.[21][22]

Salon d'Automne 1906

[edit]

The third group exhibition of the Fauves occurred at the Salon d'Automne of 1906, held from 6 October to 15 November. Metzinger exhibited his Fauvist/Divisionist Portrait of M. Robert Delaunay (no. 1191) and Robert Delaunay exhibited his painting L'homme à la tulipe (Portrait of M. Jean Metzinger) (no. 420 of the catalogue).[23] Matisse exhibited his Liseuse, two still lifes (Tapis rouge and à la statuette), flowers and a landscape (no. 1171–1175).[18][23] Robert Antoine Pinchon showed his Prairies inondées (Saint-Étienne-du-Rouvray, près de Rouen) (no. 1367), now at the Musée de Louviers,[23] painted in Fauvist style, with golden yellows, incandescent blues, thick impasto and larger brushstrokes.[24]

Paul Cézanne, who died during the show on 22 October, was represented by ten works. His works included Maison dans les arbres (no. 323), Portrait de Femme (no. 235) and Le Chemin tournant (no. 326). Van Dongen showed three works, Montmartre (492), Mademoiselle Léda (493) and Parisienne (494). André Derain exhibited 8 works, Westminster-Londres (438), Arbres dans un chemin creux (444) along with 5 works painted at l'Estaque.[23][18] Camoin entered 5 works, Dufy 7, Friesz 4, Manguin 6, Marquet 8, Puy 10, Valtat 10, and Vlaminck was represented by 7 works.[23][18]

Gallery

[edit]-

Robert Antoine Pinchon, 1904, Triel sur Seine, le pont du chemin de fer, 46 × 55 cm

-

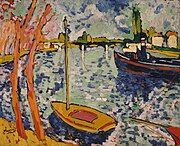

Maurice de Vlaminck, 1905–06, Barges on the Seine (Bateaux sur la Seine), oil on canvas, 81 × 100 cm, Pushkin Museum, Moscow

-

Georges Braque, 1906, L'Olivier près de l'Estaque (The Olive tree near l'Estaque). At least four versions of this scene were painted by Braque, one of which was stolen from the Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris during the month of May 2010.[25]

-

André Derain, La jetée à L'Estaque, 1906, oil on canvas, 38 × 46 cm

-

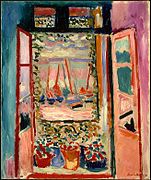

Henri Matisse, Portrait of Madame Matisse (The Green Stripe) 1906, Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen, Denmark

-

Maurice de Vlaminck, The River Seine at Chatou, 1906, Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Kees van Dongen, Woman with Large Hat, 1906

-

Jean Metzinger, 1907, Paysage coloré aux oiseaux aquatiques, oil on canvas, 74 × 99 cm, Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris

-

Othon Friesz, 1907, Paysage à La Ciotat, oil on canvas, 59.9 × 72.9 cm

See also

[edit]Notes and references

[edit]- ^ a b John Elderfield, The "Wild Beasts" Fauvism and Its Affinities, 1976, Museum of Modern Art, p.13, ISBN 0-87070-638-1

- ^ Freeman, Judi, et al., The Fauve Landscape, 1990, Abbeville Press, p. 13, ISBN 1-55859-025-0.

- ^ a b c Tate (2007). Glossary: Fauvism. Retrieved on 2007-12-19, Fauvism, Tate Archived 2020-07-31 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Freeman, 1990, p. 15.

- ^ Teitel, Alexandra J. (2005). "History: How did the Fauves come to be?". "Fauvism: Expression, Perception, and the Use of Color", Brown University. Retrieved on 2009-06-28, Brown courses Archived 2010-11-16 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Collins, Bradley, Van Gogh and Gauguin: Electric Arguments and Utopian Dreams, 2003, Westview Press, p. 159, ISBN 0-8133-4157-4.

- ^ Joshua I. Cohen, "Fauve Masks: Rethinking Modern 'Primitivist' Uses of African and Oceanic Art, 1905-8." The Art Bulletin 99, no. 2 (June 2017): 136-65.

- ^ a b Freeman, p. 243

- ^ a b c d e f g Dempsey, Amy (2002). Styles, Schools and Movements: An Encyclopedic Guide to Modern Art, pp. 66-69, London: Thames & Hudson Ltd.

- ^ a b c d "Book talk: The Unknown Matisse..." Archived 2011-10-12 at the Wayback Machine, ABC Radio National, interview with Hilary Spurling, 8 June 2005. Retrieved 1 January 2008.

- ^ "Matisse, Luxe, calme et volupté, 1904". musee-orsay.fr. Paris: Musée d'Orsay. Archived from the original on 2013-05-31. Retrieved 2013-03-14.

- ^ "Salon d'Automne, 1905". Archives of American Art.

- ^ a b Louis Vauxcelles, Le Salon d’Automne, Gil Blas, 17 October 1905. Screen 5 and 6. Gallica, Bibliothèque nationale de France Archived 21 October 2020 at the Wayback Machine, ISSN 1149-9397

- ^ a b c d Chilver, Ian (Ed.). "Fauvism" Archived 2011-11-09 at the Wayback Machine, The Oxford Dictionary of Art, Oxford University Press, 2004. Retrieved from enotes.com, 26 December 2007.

- ^ Smith, Roberta (2006). "Henri Rousseau: In imaginary jungles, a terrible beauty lurks" Archived 2022-06-12 at the Wayback Machine The New York Times, 14 July 2006. Accessed 29 December 2007

- ^ Elderfield, p.43

- ^ Salon d’automne; Société du Salon d’automne, Catalogue des ouvrages de peinture, sculpture, dessin, gravure, architecture et art décoratif. Exposés au Grand Palais des Champs-Élysées, 1905

- ^ a b c d e Russell T. Clement, Les Fauves: A Sourcebook, Greenwood Publishing Group, 1994 Archived 2022-12-30 at the Wayback Machine ISBN 0-313-28333-8

- ^ Les Demoiselles D'Avignon: Picasso's influences in the creation of a masterwork, archived from the original on 2008-02-21, retrieved 2008-03-10

- ^ Turner, Jane (1996), Grove Dictionary of Art, Macmillan Publishers, p. 372, ISBN 1-884446-00-0

- ^ Daniel Robbins, Jean Metzinger: At the Center of Cubism, 1985, Jean Metzinger in Retrospect, The University of Iowa Museum of Art, J. Paul Getty Trust, University of Washington Press, pp. 9-23

- ^ "Société des artistes indépendants: catalogue de la 22ème exposition, 1906". Archived from the original on 2018-08-05. Retrieved 2018-08-05.

- ^ a b c d e Salon d'automne; Société du Salon d'automne, Catalogue des ouvrages de peinture, sculpture, dessin, gravure, architecture et art décoratif. Exposés au Grand Palais des Champs-Élysées, 1906

- ^ François Lespinasse, Robert Antoine Pinchon: 1886–1943, 1990, repr. Rouen: Association Les Amis de l'École de Rouen, 2007, ISBN 9782906130036 (in French)

- ^ "Interpol issues global alert for stolen art" Archived 2020-09-09 at the Wayback Machine, CNN Wire Staff, May 21, 2010

Further reading

[edit]- Gerdts, William H. (1997). The Color of Modernism: The American Fauves. New York: Hollis Taggart Galleries. Archived from the original on 2017-05-27. Retrieved 2017-10-11.

- Spivey, Virginia, Fauvism, Smarthistory at Khan Academy

- Whitfield, Sarah (1991). Fauvism. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-20227-3.

External links

[edit]- Fauve Painting from the Permanent Collection at the National Gallery of Art

- Fauvism: The Wild Beasts of Early Twentieth Century Art

- Rewald, Sabine. Fauvism. In Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art (2004)

- Gelett Burgess, "The Wild Men of Paris: Matisse, Picasso and Les Fauves", Architectural Record, 1910

![Georges Braque, 1906, L'Olivier près de l'Estaque (The Olive tree near l'Estaque). At least four versions of this scene were painted by Braque, one of which was stolen from the Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris during the month of May 2010.[25]](/uploads/wikipedia/en/thumb/3/37/Georges_Braque%2C_1906%2C_L%27Olivier_pr%C3%A8s_de_l%27Estaque_%28The_Olive_tree_near_l%27Estaque%29.jpg/180px-Georges_Braque%2C_1906%2C_L%27Olivier_pr%C3%A8s_de_l%27Estaque_%28The_Olive_tree_near_l%27Estaque%29.jpg?auto=webp)