Livonian Crusade

| Livonian Crusade | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Northern Crusades | |||||||||

A Teutonic Knight on the left and a Swordbrother on the right. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Baltic and Finnic pagans (indigenous peoples) | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| History of Estonia |

|---|

|

| Chronology |

|

|

| History of Latvia |

|---|

|

| Chronology |

|

|

The Livonian crusade[3][4] consists of the various military Christianisation campaigns in medieval Livonia – modern Latvia and Estonia – during the Papal-sanctioned Northern Crusades in the 12th–13th century.

Overview

[edit]Historical sources

[edit]The main source of information on the Livonian crusade is the Livonian Chronicle of Henry, written in c. 1229 by Henry of Latvia (Henricus de Lettis).[5] In his chronicle, the author notes that he penned it down at the urging of his lords and companions, including his former teacher bishop Albert of Riga, who receives much praise throughout the text, that is internally divided according to the years of Albert's episcopate.[6] James A. Brundage (1972) posited that Albert commissioned Henry to write the Livonian Chronicle in the mid-1220s in order to glorify Albert's achievements, as well as to briefly summarise unresolved issues to the newly appointed papal legate, William of Modena.[6]

Henry wrote that the papacy's use of the crusade as a foreign policy was extended to include military expeditions against the Livonians for the first time by papal proclamation in c. 1195, and then renewed in 1197 or 1198.[7] There are no independent sources to confirm this; the earliest surviving papal letter on the Livonian crusade dates from 5 October 1199, issued by Pope Innocent III.[7] Most surviving documents relating to William of Modena's mission as legate deal with problems caused by rivalries and internal tensions within the Catholic Church in Livonia and neighbouring areas.[8] There are only scattered references to his interactions with converted populations in the Baltic, and no traces of William interacting with representatives of Novgorod, Pskov, Jersika, or non-Christian powers in the region.[9] When he returned to Rome in 1226, the Apostolic Chancery in Rome issued a series of letters and decrees on affairs in Livonia, far more detailed than any previous papal communications on the Baltic, that were very vague and showed little interest in the region.[10]

Participants

[edit]The 1199 letter of Innocent III provided that Christians who had vowed to go on pilgrimage to the Holy Land would receive an indulgence (or commutation) of penance for sins if they chose to participate in the Livonian crusade instead, and that they would receive the right to papal protection if they did.[11] Participants would be wearing the insignia of the cross, which came with specific legal obligations; unlike crusaders in the Holy Land, it meant that the wearer had to serve in the papally proclaimed crusade in Livonia for at least one year.[12]

Organisation

[edit]Unlike previous crusading enterprises that were usually started by the pope, Albert of Buxhoeveden, bishop of Riga, appears to have been the primary initiator and recruiter for the Livonian crusade.[13] Moreover, it was initially not accompanied by a papal legate either until 1224, some three decades after the crusade's launch.[14] In previous crusades, papal legates would always represent the pope, frequently preach to the crusaders, take part in military action[a], and serve a diplomatic role as the pope's spokesman on political and spiritual policies.[14] When William of Modena was finally appointed legate in late 1224, it was at the request of Albert of Riga rather than by the pope's own initiative.[15] Overseeing the crusading operation might not even have been a (great) part of William's mission, as it is not mentioned explicitly in his mandate.[15] Brundage (1972) argued that from the mid-1220s, the papacy seemed to take a more active interest in the Livonian crusade, especially by combining the military objective of conquest with the religious objective of conversion of the subjected populations.[16] In previous examples, such as the 1147 Wendish Crusade, conquest and proselytisation were more or less separate activities, without close cooperation between crusaders and missionaries.[16]

Geography

[edit]The Livonian crusade was conducted mostly by the Holy Roman Empire and the Kingdom of Denmark.[citation needed] It ended with the creation of Terra Mariana and the Danish duchy of Estonia.[citation needed] The lands on the eastern shores of the Baltic Sea were one of the last parts of Europe to be Christianised.[citation needed]

On 2 February 1207,[17] in the territories conquered, an ecclesiastical state called Terra Mariana was established as a principality of the Holy Roman Empire,[18] and proclaimed by Pope Innocent III in 1215 as a subject of the Holy See.[19] After the success of the crusade, the Teutonic- and Danish-occupied territory was divided into six feudal principalities by William of Modena.

Wars against Livs and Latgalians (1198–1209)

[edit]By the time German traders began to arrive in the second half of the 12th century to trade along the ancient trade route from the Varangians to the Greeks, some natives had already been baptized.

Saint Meinhard of Segeberg arrived in Ikšķile in 1184 with the mission of converting the pagan Livonians, and was consecrated as Bishop of Üxküll in 1186. In those days the riverside town was the center of the missionary activities in the Livonian area.

The indigenous Livonians (Līvi), who had been paying tribute to the East Slavic Principality of Polotsk,[20] and were often under attack by their southern neighbours the Semigallians, at first considered the Low Germans (Saxons) to be useful allies. The first prominent Livonian to be converted was their leader Caupo of Turaida, who was baptized around 1189.

Pope Celestine III had called for a crusade against pagans in Northern Europe in 1193. When peaceful means of conversion failed to produce results, the impatient Meinhard plotted to convert Livonians forcibly but was thwarted. He died in 1196, having failed in his mission. His appointed replacement, bishop Berthold of Hanover, a Cistercian abbot of Loccum arrived with a large contingent of crusaders in 1198. Shortly afterwards, while riding ahead of his troops in battle, Berthold was surrounded and killed, and his forces were defeated by Livonians.

To avenge Berthold's defeat, Pope Innocent III issued a bull declaring a crusade against the Livonians. Albert von Buxthoeven, consecrated as a bishop in 1199, arrived the following year with a large force, and established Riga as the seat of his Bishopric of Riga in 1201. In 1202, he formed the Livonian Brothers of the Sword to aid in the conversion of the pagans to Christianity and, more importantly, to protect German trade and secure German control over commerce.

As the German grip tightened, the Livonians and their christened chief rebelled against the crusaders. Caupo's forces were defeated at Turaida in 1206, and the Livonians were declared to be converted. Caupo subsequently remained an ally of the crusaders until his death in the Battle of St. Matthew's Day in 1217.

By 1208 the important Daugava trading posts of Salaspils (Holme), Koknese (Kokenhusen) and Sēlpils Castle (Selburg) had been taken over as a result of Albert's energetic campaigning. In the same year, the rulers of the Latgalian counties Tālava, Satekle, and Autine established military alliances with the Order, and construction began on both Cēsis Castle and a stone Koknese Castle, where the Daugava and Pērse rivers meet, replacing the wooden castle of Latgalians.

In 1209 Albert, leading the forces of the Order, captured the capital of the Latgalian Principality of Jersika, and took the wife of the ruler Visvaldis captive. Visvaldis was forced to submit his kingdom to Albert as a grant to the Archbishopric of Riga, and received back a portion of it as a fief. Tālava, weakened in wars with Estonians and Russians, became a vassal state of the Archbishopric of Riga in 1214, and in 1224 was finally divided between the Archbishopric and the Order.

-

Baltic tribes, c. 1200.

-

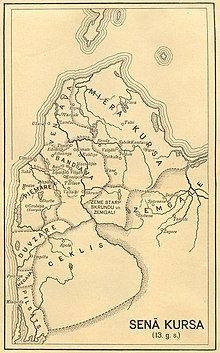

Lands of Tālava

-

Lands of Lotigola

Wars against Estonians (1208–27)

[edit]Conquest of the Estonian hinterland

[edit]By 1208 the Crusaders were strong enough to begin operations against the Estonians, who were at that time divided into eight major and seven smaller Counties, led by elders, with limited co-operation between them. With the help of the newly converted local tribes of Livs and Latgalians, the crusaders initiated raids into Sakala and Ugaunia in Southern Estonia. The Estonian tribes fiercely resisted the attacks from Riga and occasionally sacked territories controlled by the crusaders.

In 1208–27, war parties of the different sides rampaged through Livonia, Latgalia, and other Estonian counties, with the Livs, Latgalians and Russians of the Republic of Novgorod serving variously as allies of both crusaders and Estonians. Hill forts, which were the key centers of Estonian counties, were besieged, captured, and re-captured a number of times. A truce between the war-weary sides was established for three years (1213–1215). It proved generally more favourable to the Germans, who consolidated their political position, while the Estonians were unable to develop their system of loose alliances into a centralised state. They were led by Lembitu of Lehola, the elder of Sackalia, who by 1211 had come to the attention of German chroniclers as the central figure of the Estonian resistance. The Livonian leader Caupo was killed in the Battle of St. Matthew's Day near Viljandi (Fellin) on 21 September 1217,[21] but Lembitu was also killed, and the battle was a crushing defeat for the Estonians.

The Christian kingdoms of Denmark and Sweden were also eager for expansion on the eastern shores of the Baltic. In 1218 Albert asked King Valdemar II of Denmark for assistance, but Valdemar instead arranged a deal with the Order. The king was victorious in the Battle of Lindanise in Revelia in 1219, to which the origin of the Flag of Denmark is attributed. He subsequently founded the fortress Castrum Danorum, which was unsuccessfully besieged by the Estonians in 1220 and 1223. King John I of Sweden tried to establish a Swedish presence in the province of Wiek, but his troops were defeated by the Oeselians in the Battle of Lihula in 1220. Revelia, Harrien, and Vironia, the whole of northern Estonia, fell to Danish control.

During the uprising of 1223, all Christian strongholds in Estonia save Tallinn fell into Estonian hands, with their defenders killed. By 1224 all of the larger fortresses were reconquered by the crusaders, except for Tharbata, which was defended by a determined Estonian garrison and 200 Russian mercenaries. The leader of the Russian troops was Vyachko, to whom the Novgorod Republic had promised the fortress and its surrounding lands "if he could conquer them for himself".[22] Tharbata was finally captured by the crusaders in August 1224 and all its defenders were killed.

Early in 1224 Emperor Frederick II had announced at Catania that Livonia, Prussia, Sambia and a number of neighboring provinces would henceforth be considered reichsfrei, that is, subordinate directly to the Roman Catholic Church and the Holy Roman Empire only, as opposed to being under the jurisdiction of local rulers. At the end of the year Pope Honorius III announced the appointment of Bishop William of Modena as papal legate for Livonia, Prussia, and other countries.

In 1224 the Livonian Brothers of the Sword established their headquarters at Fellin (Viljandi) in Sackalia, where the walls of the Master's castle are still standing. Other strongholds included Wenden (Cēsis), Segewold (Sigulda), and Ascheraden (Aizkraukle).

The Chronicle of Henry of Livonia, one of the greatest medieval narratives, was written probably as a report for William of Modena, giving him the history of the Church in Livonia up to his time. It relates how in 1226, in the stronghold Tarwanpe, William of Modena successfully mediated a peace between the Germans, the Danes and the Vironians.

-

Counties of Ancient Estonia

-

Dannebrog falling from the sky during the Battle of Lindanise, 1219.

War against Saaremaa (1206–61)

[edit]

The last Estonian county to hold out against the invaders was the island country of Saaremaa (Ösel), whose war fleets had continued to raid Denmark and Sweden during the years of fighting against the German crusaders.

In 1206, a Danish army led by the king Valdemar II and Andreas, the Bishop of Lund, landed on Saaremaa and attempted to establish a stronghold, without success. In 1216, the Livonian Brothers of the Sword and the bishop Theodorich joined forces and invaded Saaremaa over the frozen sea. The Oeselians retaliated by raiding German-held territories in Latvia the following spring. In 1220, a Swedish army led by the king John I of Sweden and the bishop Karl of Linköping captured Lihula in Rotalia in Western Estonia. The Oeselians attacked the Swedish stronghold later the same year and killed the entire garrison, including the Bishop of Linköping.

In 1222, the Danish king Valdemar II attempted the second conquest of Saaremaa, this time establishing a stone fortress housing a strong garrison. The stronghold was besieged and surrendered within five days, the Danish garrison returning to Revel while leaving Bishop Albert of Riga's brother Theodoric and others behind as hostages for peace. The castle was leveled by the Oeselians.[23]

In 1227, the Livonian Brothers of the Sword, the town of Riga, and the Bishop of Riga organized a combined attack against Saaremaa. After the destruction of Muhu Stronghold and the surrender of Valjala Stronghold, the Oeselians formally accepted Christianity.

After the defeat of the Livonian Brothers of the Sword in the Battle of Saule in 1236 fighting again broke out on Saaremaa. In 1241 the Oeselians once again accepted Christianity by signing treaties with the Livonian Order's Master Andreas de Velven and the Bishopric of Ösel-Wiek. This was followed by a treaty signed in 1255 by the Master of the Order, Anno Sangerhausenn, and, on behalf of the Oeselians, elders whose names were phonetically transcribed by Latin scribes as Ylle, Culle, Enu, Muntelene, Tappete, Yalde, Melete, and Cake.[24] The treaty granted the Oeselians several distinctive rights regarding the ownership and inheritance of land, the social order, and the practice of religion.

Warfare erupted in 1261 as the Oeselians once more renounced Christianity and killed all the Germans on the island. A peace treaty was signed after the united forces of the Livonian Order, the Bishopric of Ösel-Wiek, and Danish Estonia, including mainland Estonians and Latvians, defeated the Oeselians by capturing their stronghold at Kaarma. Soon thereafter, the Livonian Order established a stone fort at Pöide.

On 24 July 1343 the Oeselians arose yet again, killing all the Germans on the island, drowning all the clerics, and besieging the Livonian Order's castle at Pöide. After the garrison surrendered the Oeselians massacred the defenders and destroyed the castle. In February 1344 Burchard von Dreileben led a campaign over the frozen sea to Saaremaa. The Oeselians' stronghold was conquered and their leader Vesse was hanged. In the early spring of 1345, the next campaign of the Livonian Order ended with a treaty mentioned in the Chronicle of Hermann von Wartberge and the Novgorod First Chronicle.

Saaremaa remained the vassal of the master of the Livonian Order and the Bishopric of Ösel-Wiek until 1559.

Wars against Curonians (1242–67)

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2024) |

Following the defeat of the Estonians, the crusade moved against Curonians and Semigallians, Baltic tribes living to the south and west of the Daugava river and closely allied with Samogitians.

In July 1210 Curonians attacked Riga.[25] After a day of fighting, the Curonians were unable to break through the city walls. They crossed to the other bank of the Daugava to burn their dead and mourn for three days.[26] In 1228 Curonians together with Semigallians again attacked Riga. Although they were again unsuccessful in storming the city, they destroyed a monastery in Daugavgriva and killed all the monks.

After the defeat of Estonians and Osilians in 1227, the Curonians were confronted by Lithuanian enemies in the east and south, and harassed by the Livonian Brothers of the Sword from the north; in the west, on the sea-shore, their arch-enemies, the Danes and Swedes, were lurking, waiting for an opportunity. In this hopeless situation, further aggravated by famine, the Curonians preferred to try to make peace with the Christian conquerors, inviting the monks into their country thereby escaping attacks by the Scandinavian nations.[27] In 1230 the Curonians in the northern part of Courland, under their ruler (rex) Lammekinus, signed a peace treaty with the Germans, and the lands they inhabited thus became known as Vredecuronia or Peace Courland. The southern Curonians, however, continued to resist the invaders.

In 1260, the Curonians were involved in the Battle of Durbe, one of the biggest battles in Livonia in the 13th century. They were forced to fight on the crusader side. When the battle started, the Curonians abandoned the knights. Peter von Dusburg alleged that the Curonians even attacked the Knights from the rear. The Estonians and other local people soon followed the Curonians and abandoned the Knights and that allowed the Samogitians to gain victory over the Livonian Order. It was a heavy defeat for the Order and uprisings against the crusaders soon afterwards broke out in the Curonian and Prussian lands.

Curonian resistance was finally subdued in 1266 when the whole of Courland was partitioned between the Livonian Order and the Archbishop of Riga. The Curonian nobles, among them 40 clans of the descendants of the Curonian Kings, who lived in the town of Kuldīga, preserved personal freedom and some of their privileges.[27][28]

Wars against Semigallians (1219–90)

[edit]

According to the Livonian Chronicle of Henry, Semigallians formed an alliance with bishop Albert of Riga against rebellious Livonians before 1203, and received military support to hold back Lithuanian attacks in 1205. In 1207, the Semigallian duke Viestards (Latin: dux Semigallorum) helped the christened Livonian chief Caupo conquer back his Turaida Castle from pagan rebels.

In 1219, the Semigallian–German alliance was cancelled after a crusader invasion in Semigallia. Duke Viestards promptly formed an alliance with Lithuanians and Curonians. In 1228, Semigallians and Curonians attacked the Daugavgrīva monastery, the main crusader stronghold at the Daugava river delta. The crusaders took revenge and invaded Semigallia. The Semigallians in turn pillaged land around the Aizkraukle hillfort.

In 1236, Semigallians attacked crusaders retreating to Riga after the Battle of Saule, killing many of them. After regular attacks, the Livonian Order partly subdued the Semigallians in 1254.

In 1270, the Lithuanian Grand Duke Traidenis, together with Semigallians, attacked Livonia and Saaremaa. During the Battle of Karuse on the frozen Gulf of Riga, the Livonian Order was defeated, and its master Otto von Lutterberg was killed.

In 1287, around 1400 Semigallians attacked a crusader stronghold in Ikšķile and plundered nearby lands. As they returned to Semigallia they were caught by the Order's forces, and the great Battle of Garoza began near the Garoza river. The crusader forces were besieged and badly defeated. More than 40 knights were killed, including the master of the Livonian Order Willekin von Endorp, and an unknown number of crusader allies. It was the last Semigallian victory over the growing forces of the Livonian Order.

In 1279, after the Battle of Aizkraukle, Grand Duke Traidenis of Lithuania supported a Semigallian revolt against the Livonian Order led by Duke Nameisis.

In the 1280s, the Livonian Order started a massive campaign against the Semigallians, which included burning their fields and thus causing famine. Semigallians continued their resistance until 1290, when they burned their last castle in Sidabrė and moved southwards. The Rhymed Chronicle claims that 100,000 migrated to Lithuania and once there continued to fight against the Germans.

The unconquered southern parts of Curonian and Semigallian territories (Sidabrė, Raktė, Ceklis, Mėguva etc.) were united under the rule of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

Aftermath

[edit]

In 1227 the Livonian Brothers of the Sword conquered all Danish territories in Northern Estonia. After the Battle of Saule the surviving members of the Brothers of the Sword merged into the Teutonic Order of Prussia in 1237 and became known as Livonian Order. On 7 June 1238, by the Treaty of Stensby, the Teutonic knights returned the Duchy of Estonia to Valdemar II, until in 1346, after St. George's Night Uprising, the lands were sold back to the order and became part of the Ordensstaat.

After the conquest, all of the remaining local population were ostensibly Christianized. In 1535, the first extant native language book was printed, a Lutheran catechism.[29] The conquerors upheld military control through their network of castles throughout Estonia and Latvia.[30]

The land was divided into six feudal principalities by Papal Legate William of Modena: Archbishopric of Riga, Bishopric of Courland, Bishopric of Dorpat, Bishopric of Ösel-Wiek, the lands ruled by the Livonian Brothers of the Sword and Dominum directum of King of Denmark, the Duchy of Estonia.[31][32]

Battles

[edit]- Battle of Riga (1203)

- Battle of Koknese (1205)

- Battle of Salaspils (1206)

- Battle of Turaida (1206)

- Battle of Saaremaa, 1206

- Battle of Koknese (1208)

- Battle of Otepää (1208)

- Battle of Jersika, 1209

- Battle of Otepää (1210)

- Battle of Cēsis (1210)

- Battle of Ümera, 1210

- Battle of Turaida (1211)

- Battle of Viljandi, 1211

- Battle of Lehola, 1215

- Battle of Riga (1215)

- Battle of Soontagana, 1215

- Battle of Otepää, 1217

- Battle of Soontagana, 1217

- Battle of St. Matthew's Day, 1217

- Battle of Lindanise, 1219

- Siege of Mežotne, 1219

- Battle of Lihula, 1220

- Siege of Tallinn, 1221

- Battle of Soela, 1223

- Battle of the Ümera River Bridge, 1223

- Battle of Viljandi (1223)

- Siege of Tallinn (1223)

- Siege of Tartu, 1224

- Battle of Muhu, 1227

- Siege of Aizkraukle (1229)

- Battle of Saule, 1236

- Battle on the Ice, 1242

- Battle of Durbe, 1260

- Siege of Tērvete (1259)

- Battle of Tērvete (1270)

- Battle of Aizkraukle

- Siege of Dobele (1279)

- Siege of Kernavė (1279)[33]

- Battle of Tērvete (1280)

- Siege of Dobele (1281)

- Battle of Riga (1281)

- Battle of Tērvete (1281)

- Battle of Garoza 1287

- Battle of Dobele (1290)

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Sometimes, the papal legate would even dictate the crusade's grand strategy and serve as military commander, as legate Pelagio Galvani did during the Fifth Crusade (1217–1221).[14]

References

[edit]- ^ Heinrici Chronicon Livoniae... Cap. II, 6. S. 10.

- ^ "Crusaders on the Baltic Shore – The Livonian & Estonian Crusades (c. 1198 – 1290)". The Postgrad Chronicles. August 3, 2017.

- ^ Urban, William (1981). Livonian Crusade. University Press of America. ISBN 0-8191-1683-1.

- ^ Riley-Smith, Jonathan (2005). The Crusades: A History. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 161. ISBN 0-8264-7269-9.

- ^ Brundage 1972, p. 2.

- ^ a b Brundage 1972, pp. 5–6.

- ^ a b Brundage 1972, p. 3.

- ^ Brundage 1972, p. 6.

- ^ Brundage 1972, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Brundage 1972, p. 7.

- ^ Brundage 1972, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Brundage 1972, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Brundage 1972, p. 4.

- ^ a b c Brundage 1972, pp. 4–5.

- ^ a b Brundage 1972, p. 5.

- ^ a b Brundage 1972, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Bilmanis, Alfreds (1944). Latvian–Russian Relations: Documents. The Latvian legation.

- ^ Herbermann, Charles George (1907). The Catholic Encyclopedia. Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Bilmanis, Alfreds (1945). The Church in Latvia. Drauga vēsts.

1215 proclaimed it the Terra Mariana, subject directly.

- ^ Blomkvist Nils, The Discovery of the Baltic: The Reception of a Catholic World-system in the European North (AD 1075–1225) (Leiden 2005) p. 508

- ^ Frucht, Richard (2005). Eastern Europe: An Introduction to the People, Lands, and Culture [3 Volumes]. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-57607-800-6. Retrieved 2024-11-05.

- ^ Tarvel, Enn (ed.). 1982. Henriku Liivimaa kroonika. Heinrici Chronicon Livoniae. p. 246. Tallinn: Eesti Raamat.

- ^ Urban, William L. (1994). The Baltic Crusade. Lithuanian Research and Studies Center. ISBN 978-0-929700-10-6 – via Google Books.

- ^ Hildebrand, Hermann; Schwartz, Philipp; Arbusow, Leonid; Bulmerincq, August Michael von (24 May 1970). "Liv-, est- und kurländisches Urkundenbuch: Bd. 1. 1093–1300. Bd. 2. 1301–67. Bd. 3. 1368–93, mit Nachträgen zu Bd. 1 und 2. Bd. 4. 1394–1413. Bd. 5. 1414–Mai 1423. Bd. 6. Nachträge zu Bd. 1–5. Bd. 7. Mai 1423–Mai 1429. Bd. 8. Mai 1429–35. Bd. 9. 1436–43. Bd. 10. 1444–49. Bd. 11. 1450–59. Bd. 12. 1461–72. Sachregister zu Abt. 1, Bd. 7–9". Scientia Verlag – via Google Books.

- ^ Euratlas. "Euratlas Periodis Web – Map of Livonia in Year 1500". www.euratlas.net.

- ^ Chronicle of Henry of Livonia

- ^ a b Edgar V. Saks. Aestii. 1960. p. 244.

- ^ F. Balodis. Lettland och letterna: Ha de rätt at leva. Stockholm 1943. p. 212.

- ^ Estonian Language Archived 2016-04-07 at the Wayback Machine from Estonia.eu, retrieved 12 March 2016

- ^ Harrison, Dick (2005). Gud vill det! – Nordiska korsfarare under medeltid (in Swedish). Ordfront. p. 573. ISBN 978-91-7441-373-1.

- ^ Christiansen, Eric (1997). The Northern Crusades. Penguin. ISBN 0-14-026653-4.

- ^ Knut, Helle (2003). The Cambridge History of Scandinavia: Prehistory to 1520. Cambridge University Press. p. 269. ISBN 0-521-47299-7.

- ^ "Kernavė in English". www.kernave.org.

Bibliography

[edit]- Brundage, James A. (1972). "The Thirteenth-Century Livonian Crusade: Henricus de Lettis and the First Legatine Mission of Bishop William of Modena". Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas. 20 (1). Franz Steiner Verlag: 1–9. ISSN 0021-4019. JSTOR 41044461. Retrieved 1 December 2024.

External links

[edit]- Livonian Crusade

- 13th century in Denmark

- 13th-century conflicts

- 13th-century crusades

- Conflicts involving the Livonian Order

- Medieval history of Sweden

- Military history of Estonia

- Military history of Latvia

- Northern Crusades

- Wars involving Denmark

- Wars involving Estonia

- Wars involving Latvia

- Wars involving Livonia

- Wars involving Sweden