Eritrea

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

State of Eritrea ሃገረ ኤርትራ (Tigrinya) | |

|---|---|

| Anthem: ኤርትራ ኤርትራ ኤርትራ (Tigrinya) "Eritrea, Eritrea, Eritrea" | |

| Capital and largest city | Asmara 15°20′N 38°55′E / 15.333°N 38.917°E |

| Official languages | None[1] |

| Recognised national languages | |

| Working languages | |

| Ethnic groups (2021)[3] | |

| Religion | See Religion in Eritrea |

| Demonym(s) | |

| Government | Unitary one-party presidential republic under a totalitarian dictatorship[4][5][6][7][8] |

| Isaias Afwerki | |

| Legislature | National Assembly |

| Independence from Ethiopia | |

| 1 September 1961 | |

• De facto | 24 May 1991 |

• De jure | 24 May 1993 |

| Area | |

• Total | 120,000 km2 (46,000 sq mi)[9][10][11] (97th) |

• Water (%) | negligible |

| Population | |

• 2020 estimate | 3.6–6.7 million[12][13][a] |

| GDP (PPP) | 2019 estimate |

• Total | $6.42 billion[15] |

• Per capita | $1,835[15] |

| GDP (nominal) | 2019 estimate |

• Total | $1.98 billion[15] |

• Per capita | $566[15] |

| HDI (2022) | low (175th) |

| Currency | Nakfa (ERN) |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (EAT) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (not observed) |

| Drives on | Right |

| Calling code | +291 |

| ISO 3166 code | ER |

| Internet TLD | .er |

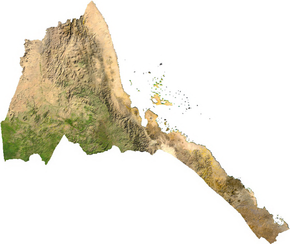

Eritrea (/ˌɛrɪˈtriːə/ ⓘ ERR-ih-TREE-ə or /-ˈtreɪ-/ -TRAY-;,[17][18][19] pronounced [ʔer(ɨ)trä] ⓘ), officially the State of Eritrea, is a country in the Horn of Africa region of Eastern Africa, with its capital and largest city being Asmara. It is bordered by Ethiopia in the south, Sudan in the west, and Djibouti in the southeast. The northeastern and eastern parts of Eritrea have an extensive coastline along the Red Sea. The nation has a total area of approximately 117,600 km2 (45,406 sq mi),[9][10] and includes the Dahlak Archipelago and several of the Hanish Islands.

Human remains found in Eritrea have been dated to 1 million years old and anthropological research indicates that the area may contain significant records related to the evolution of humans. The Kingdom of Aksum, covering much of modern-day Eritrea and northern Ethiopia, was established during the first or second century AD.[20][21] It adopted Christianity around the middle of the fourth century.[22] Beginning in the 12th century, the Ethiopian Zagwe and Solomonid dynasties held sway to a fluctuating extent over the entire plateau and the Red Sea coast. Eritrea's central highlands, known as Mereb Melash ("Beyond the Mereb"), were the northern frontier region of the Ethiopian kingdoms and were ruled by a governor titled the Bahr Negus ("King of the Sea"). In the 16th century, the Ottomans conquered the Eritrean coastline, then in May 1865 much of the coastal lowlands came under the rule of the Khedivate of Egypt, until it was transferred to Italy in February 1885. Beginning in 1885–1890, Italian troops systematically spread out from Massawa toward the highlands, eventually resulting in the formation of the colony of Italian Eritrea in 1889, establishing the present-day boundaries of the country. Italian rule continued until 1942 when Eritrea was placed under British Military Administration during World War II; following a UN General Assembly decision in 1952, Eritrea would govern itself with a local Eritrean parliament, but for foreign affairs and defense, it would enter into a federal status with Ethiopia for ten years. However, in 1962, the government of Ethiopia annulled the Eritrean parliament and formally annexed Eritrea. The Eritrean secessionist movement organised the Eritrean Liberation Front in 1961 and fought the Eritrean War of Independence until Eritrea gained de facto independence in 1991. Eritrea gained de jure independence in 1993 after an independence referendum.[23]

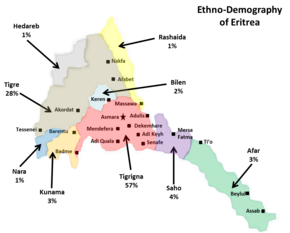

Contemporary Eritrea is a multi-ethnic country with nine recognised ethnic groups, each of which has a distinct language. The most widely spoken languages are Tigrinya and Arabic. The others are Tigre, Saho, Kuinama, Nara, Afar, Beja, Bilen and English.[24] Tigrinya, Arabic and English serve as the three working languages.[2][25][26][27] Most residents speak languages from the Afroasiatic family, either of the Ethiopian Semitic languages or Cushitic branches. Among these communities, the Tigrinyas make up about 50% of the population, with the Tigre people constituting around 30% of inhabitants. In addition, there are several Nilo-Saharan-speaking Nilotic ethnic groups. Most people in the country adhere to Christianity or Islam, with a small minority adhering to traditional faiths.[28]

Eritrea is one of the least developed countries. It is a unitary one-party presidential republic in which national legislative and presidential elections have never been held.[29][6] Isaias Afwerki has served as president since its official independence in 1993. According to Human Rights Watch, the Eritrean government's human rights record is among the worst in the world.[30] The Eritrean government has dismissed these allegations as politically motivated.[31] Freedom of the press in Eritrea is extremely limited; the Press Freedom Index consistently ranks it as one of the least free countries. As of 2022 Reporters Without Borders considers the country to be among those with the least press freedom.[32] Eritrea is a member of the African Union, the United Nations, and the Intergovernmental Authority on Development, and is an observer state in the Arab League alongside Brazil and Venezuela.[33]

Etymology

The name Eritrea is derived from the ancient (originally Greek) name for the Red Sea, the Erythraean Sea (Ἐρυθρὰ Θάλασσα Erythra Thalassa, based on the adjective ἐρυθρός erythros "red"). It was first formally adopted in 1890, with the formation of Italian Eritrea (Colonia Eritrea).[34] The name persisted throughout subsequent British and Ethiopian occupation, and was reaffirmed by the 1993 independence referendum and 1997 constitution.[35]

History

Prehistory

Madam Buya is the name of a fossil found at an archaeological site in Eritrea by Italian anthropologists. She has been identified as among the oldest hominid fossils found to date that reveal significant stages in the evolution of humans and to represent a possible link between the earlier Homo erectus and an archaic Homo sapiens. Her remains have been dated to 1 million years old. She is the oldest skeletal find of her kind and provides a link between earlier hominids and the earliest anatomically modern humans.[36] It is believed that the section of the Danakil Depression in Eritrea was a major site in terms of human evolution and may contain other traces of evolution from Homo erectus hominids to anatomically modern humans.[37]

During the last interglacial period, the Red Sea coast of Eritrea was occupied by early anatomically modern humans.[38] It is believed that the area was on the route out of Africa that some scholars suggest was used by early humans to colonize the rest of the Old World.[38] In 1999, the Eritrean Research Project Team composed of Eritrean, Canadian, American, Dutch, and French scientists discovered a Paleolithic site with stone and obsidian tools dated to more than 125,000 years old near the Gulf of Zula south of Massawa, along the Red Sea littoral. The tools are believed to have been used by early humans to harvest marine resources such as clams and oysters.[39][40][41][42]

Antiquity

Research shows tools found in the Barka Valley dating from 8,000 BC appear to offer the first concrete evidence of human settlement in the area.[43] Research also shows that many of the ethnic groups of Eritrea were the first to inhabit these areas.[44]

Excavations in and near Agordat in central Eritrea yielded the remains of an ancient pre-Aksumite civilization known as the Gash Group.[45] Ceramics were discovered that were dated back to between 2,500 and 1,500 BC.[46]

Around 2,000 BC, parts of Eritrea were most likely part of the Land of Punt, first mentioned in the twenty-fifth century BC.[47][48][49] It was known for producing and exporting gold, aromatic resins, blackwood, ebony, ivory, and wild animals. The region is known from ancient Egyptian records of trade expeditions to it, especially a well-documented expedition to Punt in approximately 1,469 BC during the reestablishment of disrupted trade routes by Hatshepsut shortly after the beginning of her rule as the king of ancient Egypt.[50][51][52][53]

Excavations at Sembel found evidence of an ancient pre-Aksumite civilization in greater Asmara. This Ona urban culture is believed to have been among the oldest pastoral and agricultural communities in East Africa. Artifacts at the site have been dated to between 800 BC and 400 BC, contemporaneous with other pre-Aksumite settlements in the Eritrean and Ethiopian highlands during the mid-first millennium BC.[54][55][56]

D'mt

Dʿmt was a kingdom that existed from the tenth to fifth centuries BC in what is now Eritrea and northern Ethiopia. Given the presence of a massive temple complex at Yeha, this area was most likely the kingdom's capital. Qohaito, often identified as the town of Koloe in the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea,[57] as well as Matara were important ancient Dʿmt kingdom cities in southern Eritrea.

The realm developed irrigation schemes, used plows, grew millet, and made iron tools and weapons. After the fall of Dʿmt in the fifth century BC, the plateau came to be dominated by smaller successor kingdoms. This lasted until the rise of one of these polities during the first century, the Kingdom of Aksum, which was able to reunite the area.[58]

Kingdom of Aksum

The Kingdom of Aksum (or Axum) was a trading empire centered in Eritrea and northern Ethiopia.[59] It existed from approximately 100–940 AD, growing from the proto-Aksumite Iron Age period around the fourth century BC to achieve prominence by the first century AD.

According to the medieval Liber Axumae (Book of Aksum), Aksum's first capital, Mazaber, was built by Itiyopis, son of Cush.[60] The capital was later moved to Axum in northern Ethiopia. The kingdom used the name "Ethiopia" as early as the fourth century.[20][21]

The Aksumites erected a number of large stelae, which served a religious purpose in pre-Christian times. One of these granite columns, the Obelisk of Aksum, is the largest such structure in the world, standing at 90 feet (27 metres).[61] Under Ezana (fl. 320–360), Aksum later adopted Christianity.[62]

Christianity was the first world religion to be adopted in modern Eritrea and the oldest monastery in the country, Debre Sina, was built in the fourth century. It is one of the oldest monasteries in Africa and the world.[63][unreliable source?] Debre Libanos, the second oldest monastery, was said to have been founded in the late fifth or early sixth century. Originally located in the village of Ham, it was moved to an inaccessible location on the edge of a cliff below the Ham plateau. Its church contains the Golden Gospel, a metal-covered bible dating to the thirteenth century during which Debre Libanos was an important seat of religious power.[64]

In the seventh century AD, early Muslims from Mecca, at least companions of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, sought refuge from Qurayshi persecution by travelling to the kingdom, a journey known in Islamic history as the First Hijrah. They reportedly built the first African mosque, that is the Mosque of the Companions in Massawa.[65]

The kingdom is mentioned in the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea as an important market place for ivory, which was exported throughout the ancient world. At the time, Aksum was ruled by Zoskales, who also governed the port of Adulis.[66] The Aksumite rulers facilitated trade by minting their own Aksumite currency.[67]

Early Modern Period

Pre-colonial Eritrea had four distinct regions divided by geography that had limited contact with each other. The Abyssinian Tigrinya-speaking Christians controlled the highlands, the nomadic Tigre and Beni Amer clans the western lowlands, the Arabic Muslims of Massawa and Dahlak, and the pastoralist Afars the Dankalia region.[68]

After the decline of Aksum, the Eritrean highlands fell under the domain of the Christian Zagwe dynasty, and later under the sphere of influence of the Ethiopian Empire.[23] The area was first known as Ma'ikele Bahri ("between the seas/rivers", i.e. the land between the Red Sea and the Mereb river), and later renamed the Medri Bahri ("Sea land" in Tigrinya).[69] The region, ruled by a local governor called the Bahr Negash, was first documented in an obscure land grant of the 11th-century Zagwe king Tatadim. He considered the unnamed Bahr Negash one of his seyyuman or "appointed ones".[70][71][72] Ethiopian Emperor Zara Yaqob strengthened imperial presence in the area by increasing the power of the Bahr Negash and placing him above other local chiefs, establishing a military colony of settlers from Shewa, and forcing the Muslims on the coast to pay tribute.[73][74]

The first Westerner to document a visit to Eritrea was Portuguese explorer Francisco Álvares in 1520. He recounted his journey through the principality ruled by the Bahr Negus, highlighting three key cities, with Debarwa as the capital. He then detailed the border demarcation at the Mereb River with the province of Tigray and recounted the difficulties in transporting certain goods across the border. His books have the first description of the local powers of Tigray and the Bahr Negus (lord of the lands by the sea)[75]

The contemporary coast of Eritrea guaranteed the connection to the region of Tigray, where the Portuguese had a small colony, and to the interior Ethiopian allies of the Portuguese. Massawa was also the stage for the 1541 landing of troops by Cristóvão da Gama in the military campaign that eventually defeated the Adal Sultanate in the battle of Wayna Daga in 1543.[76]

By 1557, the Ottomans had succeeded in occupying all of northeastern present-day Eritrea for the following two decades, an area that stretched from Massawa to Swakin in Sudan.[77] The territory became an Ottoman governorate, known as the Habesh Eyalet, with a capital at Massawa. When the city became of secondary economic importance, the administrative capital moved across the Red Sea to Jeddah.[78] The Turks tried to occupy the highlands of Eritrea in 1559 but withdrew after they encountered Resistance, pushed back by the Bahri Negash and highland forces. In 1578 they tried to expand into the highlands with the help of Bahri Negash Yisehaq, who had switched alliances due to a power struggle. Ethiopian Emperor Sarsa Dengel made a punitive expedition against the Turks in 1588 in response to their raids in the northern provinces, and apparently by 1589 they were once again compelled to withdraw to the coast. The Ottomans were eventually driven out in the last quarter of the sixteenth century. However, they retained control over the seaboard until the establishment of Italian Eritrea in the late 1800s.[77][79][80]

In 1734, the Afar leader Kedafu established the Mudaito Dynasty in Ethiopia, which later also came to include the southern Denkel lowlands of Eritrea, thus incorporating the southern Denkel lowlands into the Sultanate of Aussa.[77][81] The northern coastline of Denkel was dominated by a number of smaller Afar sultanates, such as the Sultanate of Rahayta, the Sultanate of Beylul and the Sultanate of Bidu.[82][83][84]

Italian Eritrea

The boundaries of present-day Eritrea were established during the Scramble for Africa. On 15 November 1869, the ruling local chief sold lands surrounding the Bay of Assab to the Italian missionary Giuseppe Sapeto on behalf of the Rubattino Shipping Company.[85] The area served as a coaling station along the shipping lanes introduced by the recently completed Suez Canal. In 1882, the Italian government formally took possession of the Assab colony from its commercial owners and expanded their control to include Massawa and most of the Eritrean coastal lowlands after the Egyptians withdrew from Eritrea in February 1885.[86]

In the vacuum that followed the 1889 death of Emperor Yohannes IV, Gen. Oreste Baratieri occupied the highlands along the Eritrean coast and Italy proclaimed the establishment of Italian Eritrea, a colony of the Kingdom of Italy. In the Treaty of Wuchale (It. Uccialli) signed the same year, Menelik OI of Shewa, a southern Ethiopian kingdom, recognized the Italian occupation of his rivals' lands of Bogos, Hamasien, Akkele Guzay, and Serae in exchange for guarantees of financial assistance and continuing access to European arms and ammunition. His subsequent victory over rival kings and enthronement as Emperor Menelek II (r. 1889–1913) made the treaty formally binding upon the entire territory.[87][23]

In 1888, the Italian administration launched its first development projects in the new colony. The Eritrean Railway was completed to Saati in 1888,[88] and reached Asmara in the highlands in 1911.[89] The Asmara–Massawa Cableway was the longest line in the world during its time but was later dismantled by the British in World War II. Besides major infrastructural projects, the colonial authorities invested significantly in the agricultural sector. They also oversaw the provision of urban amenities in Asmara and Massawa, and employed many Eritreans in public service, particularly in the police and public works departments.[89] Thousands of Eritreans were concurrently enlisted in the army, serving during the Italo-Turkish War in Libya as well as the First and Second Italo-Abyssinian Wars.

Additionally, the Italian Eritrea administration opened many new factories that produced buttons, cooking oil, pasta, construction materials, packing meat, tobacco, hide, and other household commodities. In 1939, there were approximately 2,198 factories and most of the employees were Eritrean citizens. The establishment of industries also increased the number of Italians and Eritreans residing in the cities. The number of Italians in the territory increased from 4,600 to 75,000 in five years; and with the involvement of Eritreans in the industry, trade and fruit plantations were expanded across the nation, and some of the plantations were owned by Eritreans.[90]

In 1922, Benito Mussolini's rise to power in Italy brought profound changes to the colonial government in Italian Eritrea. After il Duce declared the birth of the Italian Empire in May 1936, Italian Eritrea (enlarged with northern Ethiopia's regions) and Italian Somaliland were merged with the just-conquered Ethiopia into the new Italian East Africa (Africa Orientale Italiana). This Fascist period was characterized by imperial expansion in the name of a "new Roman Empire". Eritrea was chosen by the Italian government to be the industrial center of Italian East Africa.[91]

After 1935, art deco architecture was widely employed in Asmara. The Italians designed more than 400 buildings in a construction boom that only halted with Italy's involvement in World War II. These included the Fiat Tagliero Building and Cinema Impero.[92][unreliable source?] In 2017, the city was declared a World Heritage Site, described by UNESCO as featuring eclectic and rationalist built forms, well-defined open spaces, and public and private buildings, including cinemas, shops, banks, religious structures, public and private offices, industrial facilities, and residences.[93])

British administration

Through the 1941 Battle of Keren, the British expelled the Italians and took over the administration of the country.[94] Economically, the decade of British administration saw a significant restructuring of the Eritrean economy. Until 1945, the British and Americans relied on Italian equipment and skilled labor for wartime needs and to support the Allies in the Middle East. This economic boom, fueled by substantial Italian involvement, lasted until the end of the war. However, shortly after the conflict concluded, the Eritrean economy faced a combination of recession and depression that severely impacted the local urban population. War factories that had employed thousands were shut down, and Italians began to be repatriated. Additionally, many small manufacturing plants established between 1936 and 1945 were forced to close due to intense competition from factories in Europe and the Middle East.[95]

The British placed Eritrea under British military administration until Allied forces could determine its fate. In the absence of agreement amongst the Allies concerning the status of Eritrea, the British administration continued for the remainder of World War II and until 1950. During the immediate postwar years, the British proposed that Eritrea be divided along religious community lines and annexed partly to the British colony of Sudan and partly to Ethiopia. After the peace treaty with Italy was signed in 1947, the United Nations sent a Commission of Enquiry to decide the fate of the colony.[96]

Annexation by Ethiopia

In the 1950s, the Ethiopian feudal administration under Emperor Haile Selassie sought to annex Eritrea and Italian Somaliland. He laid claim to both territories in a letter to Franklin D. Roosevelt at the Paris Peace Conference and the First Session of the United Nations.[97] In the United Nations, the debate over the fate of the former Italian colonies continued. The British and Americans preferred to cede all of Eritrea except the Western province to the Ethiopians as a reward for their support during World War II.[98] The Independence Bloc of Eritrean parties consistently requested from the United Nations General Assembly that a referendum be held immediately to settle the Eritrean question of sovereignty.

The United Nations Commission of Enquiry arrived in Eritrea in early 1950 and after about six weeks returned to New York to submit its report. Two reports were presented. The minority report presented by Pakistan and Guatemala proposed that Eritrea be independent after a period of trusteeship. The majority report compiled by Burma, Norway, and the Union of South Africa called for Eritrea to be incorporated into Ethiopia.[96]

Following the adoption of U.N. Resolution 390A(V) in December 1950, Eritrea was federated with Ethiopia under the prompting of the United States.[99] The resolution called for Eritrea and Ethiopia to be linked through a loose federal structure under the sovereignty of the emperor. Eritrea was to have its own administrative and judicial structure, its own new flag, and control over its domestic affairs, including police, local administration, and taxation.[97] The federal government, which for all practical purposes was the existing imperial government, was to control foreign affairs (including commerce), defense, finance, and transportation. The resolution ignored the wishes of Eritreans for independence but guaranteed the population democratic rights and a measure of autonomy.[96]

Independence

In 1958, a group of Eritreans founded the Eritrean Liberation Movement (ELM). The organization mainly consisted of Eritrean students, professionals, and intellectuals. It engaged in clandestine political activities intended to cultivate resistance to the centralizing policies of the imperial Ethiopian state.[100] On 1 September 1961, the Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF), under the leadership of Hamid Idris Awate, waged an armed struggle for independence. In 1962, Emperor Haile Selassie unilaterally dissolved the Eritrean parliament and annexed the territory. The ensuing Eritrean War of Independence went on for 30 years against successive Ethiopian governments until 1991, when the Eritrean People's Liberation Front (EPLF), a successor of the ELF, defeated the Ethiopian forces in Eritrea and helped a coalition of Ethiopian rebel forces take control of the Ethiopian capital Addis Ababa.

In the 1980s a non-government organization called the Eritrea Inter-Agency Consortium (EIAC) aided in the development projects for the Eritrean Liberation movement.[101]

Following a referendum in Eritrea supervised by the United Nations (dubbed UNOVER) in which the Eritrean people overwhelmingly voted for independence, Eritrea declared its independence and gained international recognition in 1993.[102] The EPLF seized power, established a one-party state along nationalist lines and banned further political activity. As of 2020, there have been no elections.[103][104][105][106] On 28 May 1993, Eritrea was admitted into the United Nations as the 182nd member state.[107]

Geography

Eritrea is located in East Africa. It is bordered to the northeast and east by the Red Sea, Sudan to the west, Ethiopia to the south, and Djibouti to the southeast. Eritrea lies between latitudes 12° and 18°N, and longitudes 36° and 44°E.

The country is virtually bisected by a branch of the East African Rift. Eritrea, at the southern end of the Red Sea, is the home of the fork in the rift. The Dahlak Archipelago and its fishing grounds are situated off the sandy arid coastline.

Eritrea may be split into three ecoregions. A hot arid coastal plain extends along the coast. The coastal plain is narrow in the west and widens towards the east. These coastal lowlands are part of the Djibouti xeric shrublands ecoregion. The cooler, more fertile highlands reach up to 3,000 m (9,800 ft) and are a northern extension of the Ethiopian Highlands, I home to montane grasslands and woodlands.[108] Habitats here vary from the sub-tropical rainforest at Filfil Solomona to the precipitous cliffs and canyons of the southern highlands.[109] Filfil receives over 1,100 mm of rainfall annually.[110] There is a steep escarpment along the eastern side of the highlands, which is the western wall of the East African Rift. The western slope of the highlands is more gradual, descending to interior lowlands. Southwestern Eritrea is drained by the Atbara River, which flows northwestwards to join the Nile. The northwestern slope of the highlands is drained by the Barka River, which flows northwards into Sudan to empty into the Red Sea.[111] Western Eritrea is part of the Sahelian Acacia savanna, which extends across Africa south of the Sahara from Eritrea to Senegal.[112]

The Afar Triangle or Danakil Depression of Eritrea is the probable location of a triple junction where three tectonic plates are pulling away from one another. The highest point of the country, Emba Soira, is located in the center of Eritrea, at 3,018 m (9,902 ft) above sea level. Eritrea has volcanic activity in the southeastern parts of the country. In 2011 Nabro Volcano had an eruption.

The main cities of the country are the capital city of Asmara and the port town of Asseb in the southeast, as well as the towns of Massawa to the east, the northern town of Keren, and the central town Mendefera.

Local variability in rainfall patterns and reduced precipitation are known to occur, which may precipitate soil erosion, floods, droughts, land degradation, and desertification.[113]

Eritrea is part of a 14-nation constituency within the Global Environment Facility, which partners with international institutions, civil society organizations, and the private sector to address global environmental issues while supporting national sustainable development initiatives.[114]

In 2006, Eritrea announced that it would become the first country in the world to turn its entire coast into an environmentally protected zone. The 1,347 km (837 mi) coastline, along with another 1,946 km (1,209 mi) of coast around its more than 350 islands, will come under governmental protection.

Climate

Based on temperature variations, Eritrea can be broadly divided into three major climate zones: the temperate zone, subtropical climate zone, and tropical climate zone.[115]

The climate of Eritrea is shaped by its diverse topographical features and its location within the tropics. The diversity of its landscape and topography in the highlands and lowlands of Eritrea results in a diversity of climate. The highlands have a temperate climate throughout the year. The climate of most lowland zones is arid and semiarid. The distribution of rainfall and vegetation types varies markedly throughout the country. Eritrean climate varies based on seasonal and altitudinal differences.

Due to its physical diversity, Eritrea is one of the few countries where one can experience "four seasons in a day".[116] In the highlands (up to 3000m above sea level) the hottest month is usually May, with temperatures reaching 30 C, whereas winter occurs during December to February when temperatures can be as low as 10 C at night. The capital, Asmara, has a pleasant temperature all year round.

In the lowlands and the coastal areas, summer occurs from June to September, when temperatures can reach 40 C. Winter in the lowlands occurs from February to April, when temperatures are between 21 and 35 C.[117]

A 2022 analysis found that the expected costs for Eritrea to adapt to and avert the environmental consequences of climate change are going to be high.[118]

Biodiversity

Eritrea has several species of mammals and a rich avifauna of 560 species of birds.[119]

Eritrea is home to a large number of mammals; 126 species of mammals, 90 species of reptiles, and 19 species of amphibians have been recorded.[120] Enforced regulations have helped in steadily increasing their numbers throughout Eritrea.[121] Mammals commonly seen today include the Abyssinian hare, African wild cat, Black-backed jackal, African golden wolf, Genet, Ground squirrel, pale fox, Soemmerring's gazelle, and warthog. Dorcas gazelle are common on the coastal plains and in Gash-Barka.

Lions are said to inhabit the mountains of the Gash-Barka Region. Dik-diks may be found in many areas. The endangered African wild ass may be seen in Denakalia Region. Other local wildlife include bushbuck, duikers, greater kudu, Klipspringer, African leopards, oryx, and crocodiles.[122][123] The spotted hyena is widespread and fairly common.

Historically, a small population of African bush elephants roamed some parts of the country. Between 1955 and 2001 there were no reported sightings of elephant herds, however, and they were thought to have fallen victim to the war of independence. In December 2001, a herd of approximately 30, including 10 juveniles, was observed in the vicinity of the Gash River. The elephants seemed to have formed a symbiotic relationship with olive baboons. The baboons use the water holes dug by the elephants and the elephants seem to be taking advantage of vocalizations made by baboons from the tree tops as an early warning system. It is estimated that there are approximately 100 African bush elephant left in Eritrea, the most northerly of the East African elephants.[124]

The endangered African wild dog (Lycaon pictus) was previously found in Eritrea but is now deemed extirpated from the entire country.[125] In Gash-Barka, snakes such as saw-scaled viper are common. Puff adder and red spitting cobra are widespread and may be found even in the highlands. In the coastal areas, common marine species include dolphin, dugong, whale shark, turtles, marlin, swordfish, and manta ray.[123] 500 fish species, 5 marine turtles, 8 or more cetaceans, and the dugong have been recorded in the country.[120]

Eritrea also harbours many species only found in Eritrea, these include various bugs, frogs, mammals, snakes, and plants.[126]

Over 700 plants have been recorded in Eritrea, including marine plants and seagrass.[120][127] In Eritrea 26% of is arable land.[128] Eritrea has diverse habitats, including Tropical and Subtropical Grasslands, Savannas, Shrublands, Deserts, Xeric Shrublands, Tropical and Subtropical Moist Broadleaf Forests and Mangrove forests.[129][130]

All of Eritrea's national parks are protected, which include Dahlak Marine National Park, Nakfa Wildlife Reserve, Gash-Setit Wildlife Refuge, Semenawi Bahri National Park, and Yob Wildlife Reserve.[131]

Government and politics

The People's Front for Democracy and Justice (PFDJ) is the only legal party in Eritrea.[132] Other political groups are not allowed to organize, although the unimplemented Constitution of 1997 provides for the existence of multi-party politics. The National Assembly has 150 seats. National elections have been periodically scheduled and cancelled; as of 2022, none have ever been held in the country.[28] President Isaias Afwerki has been in office since independence in 1993.

In 1993, 75 representatives were elected to the National Assembly; the rest were appointed. As the report by the United Nations Human Rights Council explained: "No national elections have taken place since that time, and no presidential elections have ever taken place. Local or regional elections have not been held since 2003–2004. The National Assembly elected independent Eritrea's first president, Isaias Afwerki, in 1993. Following his election, Afwerki consolidated his control of the Eritrean government." President Isaias Afwerki has regularly expressed his disdain for what he refers to as "Western-style" democracy. In a 2008 interview with Al Jazeera, for example, the president stated that "Eritrea will wait three or four decades, maybe more, before it holds elections. Who knows?"[133] According to 2023 V-Dem Democracy indices Eritrea is 2nd lowest ranked worldwide and the lowest ranked electoral democracy in Africa.[134]

National, regional, and local elections

Given that the full implementation of the Joint Declaration of Peace and Friendship between Eritrea and Ethiopia is still incomplete, the Eritrean authorities still do not consider that the peace agreement is formally implemented. However, local elections were held for a time in Eritrea. The most recent round of local government elections were in 2010 and 2011.

Administrative divisions

Eritrea is divided into six administrative regions. These areas are further divided into 58 districts.

| Region | Area (km2) | Capital |

|---|---|---|

| Central | 1,300 | Asmara |

| Anseba | 23,200 | Keren |

| Gash-Barka | 33,200 | Barentu |

| Southern | 8,000 | Mendefera |

| Northern Red Sea | 27,800 | Massawa |

| Southern Red Sea | 27,600 | Assab |

The regions of Eritrea are the primary geographical divisions through which the country is administered. Six in total, they include the Maekel/Central, Anseba, Gash-Barka, Debub/Southern, Northern Red Sea, and Southern Red Sea regions. At the time of independence in 1993, Eritrea was arranged into ten provinces. These provinces were similar to the nine provinces operating during the colonial period. In 1996, these were consolidated into six regions (zobas). The boundaries of these new regions are based on water catchment basins.

Foreign relations

Eritrea is a member of the United Nations and the African Union. It is an observing member of the Arab League, alongside Brazil and Venezuela.[33] The nation holds a seat on the United Nations Advisory Committee on Administrative and Budgetary Questions (ACABQ). Eritrea also holds memberships in the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, International Finance Corporation, International Criminal Police Organization (INTERPOL), Non-Aligned Movement, Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, Permanent Court of Arbitration, Port Management Association of Eastern and Southern Africa, and the World Customs Organization.

The Eritrean government previously withdrew its representative to the African Union to protest the AU's alleged lack of leadership in facilitating the implementation of a binding border decision demarcating the border between Eritrea and Ethiopia. Since January 2011, the Eritrean government has appointed an envoy, Tesfa-Alem Tekle, to the AU.[135]

Its relations with Djibouti and Yemen are tense due to territorial disputes over the Doumeira Islands and Hanish Islands, respectively.

On 28 May 2019, the United States removed Eritrea from the "Counterterror Non-Cooperation List" which also includes Iran, North Korea, Syria, and Venezuela.[136] Moreover, Eritrea was visited two months earlier by a U.S. congressional delegation for the first time in 14 years.[137]

Along with Belarus, Syria, and North Korea, Eritrea was one of only four countries not including Russia to vote against a United Nations General Assembly resolution condemning Russia's 2022 invasion of Ukraine.[138]

Relations with Ethiopia

The undemarcated border with Ethiopia is the primary external issue currently facing Eritrea. Eritrea's relations with Ethiopia turned from that of cautious mutual tolerance, following the 30-year war for Eritrean independence, to a deadly rivalry that led to the outbreak of hostilities from May 1998 to June 2000 that claimed approximately 70,000 lives from both sides.[139] The border conflict cost hundreds of millions of dollars.[140] The Eritrean–Ethiopian War from 1998 to 2000 involved a major border conflict, notably around Badme and Zalambessa, eventually resolved in 2018.[citation needed]

Disagreements following the war have resulted in stalemates punctuated by periods of elevated tension and renewed threats of war.[141][142][143] The stalemate led the president of Eritrea to urge the UN to take action on Ethiopia with the Eleven Letters penned by the president to the United Nations Security Council. The situation has been further escalated by the continued efforts of the Eritrean and Ethiopian leaders in supporting the opposition in one another's countries.[144][145] In 2011, Ethiopia accused Eritrea of planting bombs at an African Union summit in Addis Ababa, which was later supported by a UN report. Eritrea denied the claims.[146]

A peace treaty between both nations was signed on 9 July 2018.[147] The next day, they signed a joint declaration that formally ended the Eritrean–Ethiopian border conflict.[148][149]

In 2020, Eritrean troops intervened in Tigray War on the side of the Ethiopian government.[150][104][105][106] In April 2021, Eritrea confirmed its troops were fighting in Ethiopia.[151]

Military

The Eritrean Defence Forces are the official armed forces of the State of Eritrea. Eritrea's military is one of the largest in Africa.[152]

Compulsory military service was instituted in 1995. Officially, conscripts, male and female, must serve for 18 months minimum, which includes six months of military training and 12 months during the regular school year to complete their last year of high school. Thus around 5% of Eritreans do military service at Sawa facilities, but also by doing projects such as road building as part of their service.[citation needed]

The National Service Proclamation of 1995 does not recognize the right to conscientious objection to military service. According to the 1957 Ethiopian penal code adopted by Eritrea during independence, failure to enlist in the military or refusal to perform military service are punishable with imprisonment terms of six months to five years and up to ten years, respectively.[153] National service enlistment times may be extended during times of "national crisis"; since 1998, everyone under the age of 50 is enlisted in national service for an indefinite period until released, which may depend on the arbitrary decision of a commander. In a study of 200 escaped conscripts, the average service was 6.5 years, and some had served more than 12 years.[154]

Legal profession

According to the NYU School of Law, the Legal Committee of the Ministry of Justice oversees the admission and requirements to practice law in Eritrea. Although the establishment of an independent bar association is not proscribed under Proclamation 88/96, among other domestic laws, there is no bar association. The community electorate in the local jurisdiction of the Community Court chooses the court judges. The Community Court's standing on women in the legal profession is unclear but elected women judges have reserved seats.[155]

Human rights

Eritrea is a one-party state in which national legislative elections have been repeatedly postponed.[29] According to Human Rights Watch, the government's human rights record is considered among the worst in the world.[30] Most countries have accused the Eritrean authorities of arbitrary arrest and detentions, and of detaining an unknown number of people without charge for their political activism. Both male and female same-sex sexual activity are illegal in Eritrea.[156]

A prominent group of fifteen Eritreans, called the G-15, including three cabinet members, were arrested in September 2001 after publishing an open letter to the government and President Isaias Afewerki calling for democratic dialogue. This group and thousands of others who were alleged to be affiliated with them are imprisoned without legal charges, hearing, trial, or judgment.[157][158]

Since Eritrea conflicted with Ethiopia in 1998–2001, the nation's human rights record has been criticized by the United Nations.[159] Human rights violations are allegedly often committed by the government or on behalf of the government. Freedom of speech, press, assembly, and association are limited. Those who practice "unregistered" religions, try to flee the nation, or escape military duty are arrested and put into prison.[159] By 2009, the number of political prisoners was in the range of 10,000–30,000, there was widespread and systematic torture and extrajudicial killings, with "anyone" for "any or no reason", including children eight years old, people more than 80 years old, and ill people, being liable to be arrested, and Eritrea was "one of the world's most totalitarian and human rights-abusing regimes".[160] During the Eritrean independence struggle and 1998 Eritrean-Ethiopian War, many atrocities were committed by the Ethiopian authorities against unarmed Eritrean civilians.[161][162]

In June 2016, a 500-page United Nations Human Rights Council report accused the Eritrean government of extrajudicial executions, torture, indefinitely prolonged national service (6.5 years on average), and forced labour, and it indicated that among state officials, sexual harassment, rape, and sexual servitude practices are widespread.[4][163] Barbara Lochbihler of the European Parliament Subcommittee on Human Rights said the report detailed 'very serious human rights violations', and asserted that EU funding for development would not continue as at present without change in Eritrea.[164] The Eritrean Foreign Ministry responded by describing the commission's report as being "wild allegations" that were "totally unfounded and devoid of all merit".[165] Representatives of the United States and China disputed the report's language and accuracy.[166]

All Eritreans aged between 18 and 40 years must complete a mandatory national service, which includes military service. This requirement was implemented after Eritrea gained independence from Ethiopia, as a means to protect Eritrea's sovereignty, to instill national pride, and to create a disciplined populace.[154] Eritrea's national service requires long, indefinite conscription (6.5 years on average), which some Eritreans leave the country to avoid.[154][167][168]

In an attempt at reform, Eritrean government officials and NGO representatives in 2006 participated in many public meetings and dialogues. In these sessions, they answered questions as fundamental as, "What are human rights?", "Who determines what are human rights?", and "What should take precedence, human or communal rights?".[169]

In 2007, the Eritrean government banned female genital mutilation.[170] In Regional Assemblies and religious circles, Eritreans themselves speak out continuously against the use of female circumcision. They cite health concerns and individual freedom as being of primary concern when they say this. Furthermore, they implore rural peoples to cast away this ancient cultural practice.[171][172]

In 2009, a movement called Citizens for Democratic Rights in Eritrea was formed to create dialogue between the government and political opposition. The group consists of ordinary citizens and some people close to the government.[173] Since the movement's creation, no significant effort has been made by the Eritrean government to improve its record on human rights.

In July 2019, UN ambassadors of 37 countries, including Eritrea, signed a joint letter to the UNHRC defending China's treatment of Uyghurs and other Muslim minority groups in the Xinjiang region.[174] Eritrea continued this support in 2020.[175]

Eritrea claims Western media stories of the country are decontextualized, sometimes fabricated, and almost always deployed to build a regime change narrative.[176] It claims it's being targeted for not conforming to the West's agenda towards African countries,[177] for instance by refusing to accept humanitarian foreign aid. Eritrea aspires to be self-reliant and has since 2005 rejected foreign aid because it sees aid as a hindrance to true economic development. In 2006 alone, Eritrea walked away from US$200 million in foreign aid. The same year it also refused a US$100 million loan from the World Bank.[178]

Besides accusing the West of deliberate demonization through smear-campaigns, it also sees itself targeted by sanctions and western supported war against Eritrea through the Ethiopian group TPLF.[179] It also accuses the west of luring Eritreans abroad by purposely granting many Eritreans political asylum.[180][181][182][176]

Media freedom

In its 2023 Press Freedom Index, Reporters Without Borders ranked the media environment in Eritrea at 174.[183][184] According to the BBC, "Eritrea is the only African country to have no privately owned news media",[185] and Reporters Without Borders said of the public media, "[They] do nothing but relay the regime's belligerent and ultra-nationalist discourse... Not a single [foreign correspondent] now lives in Asmara."[186] The state-owned news agency censors news about external events.[187] Independent media have been banned since 2001.[187] The Eritrean authorities had reportedly imprisoned the fourth highest number of journalists after Turkey, China, and Egypt.[188]

The 2024 Edelstam Prize was awarded to journalist Dawit Isaak who Eritrean authorities have imprisoned since 2001 without legal process.[189]

Economy

In 2020, the IMF estimated Eritrea's GDP at $2.1 billion, or $6.4 billion on a PPP basis.[190] Between 2016 and 2019 Eritrea had a GDP growth between 7,6 %-10,2 %, down from the peak at 30,9% in 2014. In 2023 the GDP growth is expected to be 2,8%, a decrease due to factors such as the Ukraine and Russia war impacting the global economy and the effects of COVID-19 on value chains. However, the country's economy is expecting a steady growth in coming years.[191][192][193]

Mining and agriculture in 2021 account for 20% of the GDP. As of 2020, remittances from abroad were estimated to account for 12% of gross domestic product.[194][195]

Mining

Mining accounts for about 20% of GDP in 2021.[195] In 2013, the pickup in growth had been attributed to the commencement of full operations in the gold and silver Bisha Mine by Canadian Nevsun Resources (now Chinese Zijin Mining[196]), the production of cement from the cement factory in Massawa,[197] and investment in Eritrea's copper, zinc, and Colluli potash mining operations by Australian[198] and Chinese[199] mining companies.

Agriculture

Since independence, Eritrea has constructed 187 dams, each with a capacity of over 50,000 m3 and the biggest ones with a capacity of 350 million m3 in size. These have been built to combat drought, for agriculture, fishing, and energy purposes. In addition, 600 micro-dams have been built.[200] [206]

Energy

Annual consumption of petroleum in 2001 was estimated at 370,000 tons. Eritrea has no domestic petroleum production; the Eritrean Petroleum Corporation conducts purchases through international competitive tender. According to the U.S. Department of Commerce, opportunities exist for both on- and offshore oil and natural gas exploration; however, these prospects have yet to come to fruition. The use of wind energy, solar power, hydropower has slightly increased, due to the growth of solar power manufacturing companies in the country. The Eritrean government has expressed interest in developing alternative energy sources, including geothermal, solar, and wind power.[207]

Tourism

Tourism made up 2% of Eritrea's economy up to 1997. After 1998, revenue from the industry fell to one-quarter of 1997 levels. In 2006, it made up less than 1% of the country's GDP.[208]

Eritrea is a member of World Tourism Organization which calculated that the country's international tourism receipts in 2002 were US$73 million.[209] Sources from 2015 state that most tourists are members of the Eritrean diaspora. Overall visitors have steadily increased in recent years and annual visitors were 142,000 as of 2016.[210]

Tourism in Eritrea has seen increased attention in later years. For instance, in 2019, the country was added to National Geographic's Cool List. Highlighted areas included the capital, Asmara, known for its art deco architecture; the Dahlak Islands; and the country's wilderness areas.[211] Lonely Planet also lists the capital Asmara, the Dahlak Islands, the city of Massawa and archeological sites as top attractions.[212]

The nation's flag carrier, Eritrean Airlines, had no scheduled service as of July 2023. International visitors rely on alternatives such as Ethiopian Airlines and Turkish Airlines, to get to the country.[213]

The government has started a twenty-year tourism development plan entitled "the 2020 Eritrea Tourism Development Plan" to develop the country's tourist industry, aiming to enhance the rich cultural and natural resources of the country. The country is a participant in many tourism trade fairs to promote the tourism of the country. [208]

Transportation

Transport in Eritrea includes highways, airports, railways, and seaports, in addition to various forms of public and private vehicular, maritime, and aerial transportation.

The Eritrean highway system is named according to the road classification. The three levels of classification are: primary (P), secondary (S), and tertiary (T). The lowest level road is tertiary and serves local interests. Typically, the tertiary ones are improved earth roads that occasionally are paved. During the wet seasons, these roads typically become impassable.

The next higher-level road is a secondary road and typically is a single-layered asphalt road that connects district capitals and those to the regional capitals. Roads that are considered primary roads are those that are fully constructed of asphalt (throughout their entire length) and in general, they carry traffic between all the major cities and towns in Eritrea.

As of 1999, there is a total of 317 kilometres of 950 mm (3 ft 1+3⁄8 in) (narrow gauge) rail line in Eritrea. The Eritrean Railway was built between 1887 and 1932.[214][215] Badly damaged during World War II and in later fighting, it was closed section by section, with the final closure coming in 1978.[216] After independence, a rebuilding effort commenced, and the first rebuilt section was reopened in 2003. As of 2009, the section from Massawa to Asmara was fully rebuilt and available for service.

Rehabilitation of the remainder and the rolling stock has occurred in recent years. Current service is very limited due to the extreme age of most of the railway equipment and its limited availability. Further rebuilding is planned. The railway linking Agordat and Asmara with the port of Massawa had been inoperative since 1978 except for an approximately 5-kilometre stretch that was reopened in Massawa in 1994. A railway formerly ran from Massawa to Bishia via Asmara and is under reconstruction.

Even during the war, Eritrea developed its transportation infrastructure by asphalting new roads, improving its ports, and repairing war-damaged roads and bridges as a part of the Wefri Warsay Yika'alo program. The most significant of these projects was the construction of a coastal highway of more than 500 km connecting Massawa with Asseb, as well as the rehabilitation of the Eritrean Railway. The rail line has been restored between the port of Massawa and the capital Asmara, although services are sporadic. Steam locomotives are sometimes used for groups of enthusiasts.

Demographics

Sources disagree as to the current population of Eritrea, with some proposing numbers as low as 3.6 million[12] and others as high as 6.7 million.[13] Eritrea has never conducted an official government census.[14] The proportion of children below the age of 15 in 2020 was 41.1%, 54.3% were between 15 and 65 years of age, while 4.5% were 65 or older.[217]

In 2015, there was a major outflow of emigrants from Eritrea. The Guardian attributed the emigration to Eritrea being "a totalitarian state where most citizens fear arrest at any moment and dare not speak to their neighbours, gather in groups or linger long outside their homes", with a major factor being the conditions and long durations of conscription in the Eritrean Army.[218] At the end of 2018, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) estimated that about 507,300 Eritreans were refugees who had fled Eritrea.[219]

Urbanization

| Rank | Name | Region | Pop. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Asmara  Keren |

1 | Asmara | Maekel | 963,000 |  Dekemhare  Massawa | ||||

| 2 | Keren | Anseba | 120,000 | ||||||

| 3 | Dekemhare | Debub | 120,000 | ||||||

| 4 | Massawa | Semienawi Keyih Bahri | 54,090 | ||||||

| 5 | Mendefera | Debub | 53,000 | ||||||

| 6 | Assab | Debubawi Keyih Bahri | 28,000 | ||||||

| 7 | Barentu | Gash-Barka | 15,891 | ||||||

| 8 | Adi Keyh | Debub | 13,061 | ||||||

| 9 | Edd | Southern Red Sea | 11,259 | ||||||

| 10 | Ak'ordat | Gash-Barka | 8,857 | ||||||

Ethnic composition

There are nine recognized ethnic groups according to the government of Eritrea.[28][220] An independent census has yet to be conducted, but the Tigrinya people make up approximately 55% and Tigre people make up approximately 30% of the population. A majority of the remaining ethnic groups belong to Afroasiatic-speaking communities of the Cushitic branch, such as the Saho, Hedareb, Afar, and Bilen. There are also several Nilotic ethnic groups, who are represented in Eritrea by the Kunama and Nara. Each ethnicity speaks a different native tongue but, typically, many of the minorities speak more than one language.

The Arabic Rashaida people represent approximately 2% of Eritrea's population.[221] They reside in the northern coastal lowlands of Eritrea as well as the eastern coasts of Sudan. The Rashaida first came to Eritrea in the nineteenth century from the Hejaz region.[222]

In addition, there exist Italian Eritrean (concentrated in Asmara) and Ethiopian Tigrayan communities. Neither is generally given citizenship unless through marriage or, more rarely, by having it conferred upon them by the state. In 1941, Eritrea had approximately 760,000 inhabitants, including 70,000 Italians.[223] Most Italians left after Eritrea became independent from Italy. It is estimated that as many as 100,000 Eritreans are of Italian descent.[224][225]

Languages

Eritrea is a multilingual country. The nation has no official language, as the Constitution establishes the "equality of all Eritrean languages".[1] Eritrea has nine national languages which are Tigrinya, Tigre, Afar, Beja, Bilen, Kunama, Nara, and Saho. Tigrinya, Arabic, and English serve as de facto working languages, with English used in university education and many technical fields. While Italian, the former colonial language, holds no government-recognised status in Eritrea, it is spoken by a few monolinguals and Asmara had the Scuola Italiana di Asmara, an Italian government-operated school that was shut down in 2020.[226] Also, native Eritreans assimilated the language of the Italian Eritreans and spoke a version of Italian mixed with many Tigrinya words: Eritrean Italian.[227]

Most of the languages spoken in Eritrea belong to the Ethiopian Semitic branch of the Afroasiatic family.[228] Other Afroasiatic languages belonging to the Cushitic branch are also widely spoken in the country.[228] The latter include Afar, Beja, Blin, and Saho. In addition, Nilo-Saharan languages (Kunama and Nara) are spoken as a native language by the Nilotic Kunama and Nara ethnic groups that live in the western and northwestern part of the country.[228]

Smaller groups speak other Afroasiatic languages, such as the newly recognized Dahlik and Arabic (the Hejazi and Hadhrami dialects spoken by the Rashaida and Hadhrami, respectively).

Religion

The two main religions followed in Eritrea are Christianity and Islam. However, the number of adherents of each faith is subject to debate. According to the Pew Research Center, as of 2020[update], 62.9% of the population of Eritrea adhered to Christianity, 36.6% followed Islam, and 0.4% practiced traditional African religions. The remainder observed Judaism, Hinduism, Buddhism, other faiths (<0.1% each), or were religiously unaffiliated (0.1%).[229] The U.S. Department of State estimated that as of 2019[update], 49% of the population of Eritrea adhered to Christianity, 49% followed Islam, and 2% observed other religions, including traditional faiths and animism.[230] The World Religion Database reports that in 2020, 47% of the population were Christian and 51% were Muslim.[231] Christianity is the oldest world religion practiced in the country, and the first Christian monastery Debre Sina was built during the fourth century. [232]

Since May 2002, the government of Eritrea has officially recognized the Eritrean Orthodox Tewahedo Church (Oriental Orthodox), Sunni Islam, the Eritrean Catholic Church (a Metropolitanate sui juris), and the Evangelical Lutheran church. All other faiths and denominations are required to undergo a registration process.[233] Among other things, the government registration system requires religious groups to submit personal information on their membership to be allowed to worship.[233]

The Eritrean government is against what it deems as "reformed" or "radical" versions of its established religions. Therefore, alleged radical forms of Islam and Christianity, Jehovah's Witnesses, and numerous other Protestant Evangelical denominations are not registered and cannot worship freely. Three named Jehovah's Witnesses are known to have been imprisoned since 1994 along with 51 others.[234][235][236] The government treats Jehovah's Witnesses especially harshly, denying them ration cards and work permits.[237] Jehovah's Witnesses were stripped of their citizenship and basic civil rights by presidential decree in October 1994.[238]

In its 2017 religious freedom report, the U.S. State Department named Eritrea a Country of Particular Concern (CPC).[239]

Health

Eritrea has achieved significant improvements in health care and is one of the few countries to be on target to meet its Millennium Development Goals (MDG) for health, in particular child health.[240] Life expectancy at birth increased from 39.1 years in 1960 to 66.44 years in 2020;[241] maternal and child mortality rates dropped dramatically and the health infrastructure expanded.[240]

The World Health Organisation (WHO) in 2008 found average life expectancy to be slightly less than 63 years, a number that has increased to 66.44 in 2020.[241][failed verification] Immunisation and child nutrition have been tackled by working closely with schools in a multi-sectoral approach; the number of children vaccinated against measles almost doubled in seven years, from 40.7% to 78.5% and the prevalence of underweight children decreased by 12% from 1995 to 2002 (severe underweight prevalence by 28%).[240] The National Malaria Protection Unit of the Ministry of Health registered reductions in malarial mortality by as much as 85% and in the number of cases by 92% between 1998 and 2006.[240] The Eritrean government has banned female genital mutilation (FGM), saying the practice was painful and put women at risk of life-threatening health problems.[242]

However, Eritrea still faces many challenges. Although the number of physicians increased from only 0.2 in 1993 to 0.5 in 2004 per 1000 people, this is still very low.[240] Malaria and tuberculosis are common.[243] HIV prevalence for ages 15 to 49 years exceeds 2%.[243] The fertility rate is about 4.1 births per woman.[243] Maternal mortality dropped by more than half from 1995 to 2002 but is still high.[240] Similarly, the number of births attended by skilled health personnel doubled from 1995 to 2002 but still is only 28.3%.[240] A major cause of death in newborns is severe infection.[243] Per-capita expenditure on health is low.[243]

Education

There are five levels of education in Eritrea: pre-primary, primary, middle, secondary, and post-secondary. There are nearly 1,270,000 students in the primary, middle, and secondary levels of education.[244] There are approximately 824 schools,[245] two universities, (the University of Asmara and the Eritrea Institute of Technology), and several smaller colleges and technical schools.

The Eritrea Institute of Technology "EIT" is a technological institute located near the town of Himbrti, Mai Nefhi outside Asmara. The institute has three colleges: Science, Engineering and Technology, and Education. The institute began with approximately 5,500 students during the 2003–2004 academic year. The EIT was opened after the University of Asmara was reorganized. According to the Ministry of Education, the institution was established, as one of many efforts to achieve equal distribution of higher learning in areas outside the capital city, Asmara. Accordingly, several similar colleges have also been established in other parts of the country. The Eritrea Institute of Technology is the main local institute of higher studies in science, engineering, and education. The University of Asmara is the oldest in the country and was opened in 1958.[246] It is currently not in operation.

As of 2018, the overall adult literacy rate in Eritrea is 76.6% (84.4% for men and 68.9% for women). For youth 15–24, the overall literacy rate is 93.3% (93.8% for men and 92.7% for women).[247]

Education in Eritrea is officially compulsory for children aged 6 to 13 years.[244] Statistics vary at the elementary level, suggesting that 70% to 90% of school-aged children attend primary school; approximately 61% attend secondary school. Student-teacher ratios are high: 45:1 at the elementary level and 54:1 at the secondary level. Class sizes average 63 and 97 students per classroom at the elementary and secondary school levels, respectively.[citation needed]

Barriers to education in Eritrea include traditional taboos, school fees (for registration and materials), and the opportunity costs of low-income households.[248]

Culture

The culture of Eritrea is the collective cultural heritage of the various populations native to Eritrea and its rich cultural heritage inherited through its long history. Modern-day Eritrea is also defined by the struggle for independence.[249][250] The nation has a rich oral and literary tradition which ranges across all nine ethnic groups, it includes a wealth of poetry and proverbs, songs and chants, folk tales, histories and legends. It also has a rich history in theatre and painting, often colourful and depicting a reflection of the Eritrean people's history.[251]

One of the most recognizable parts of Eritrean culture is the coffee ceremony.[252] Coffee (Ge'ez ቡን būn) is offered when visiting friends, during festivities, or as a daily staple of life. During the coffee ceremony, some traditions are upheld. The coffee is served in three rounds: the first brew or round is called awel in Tigrinya (meaning "first"), the second round is called kalaay (meaning "second"), and the third round is called bereka (meaning "to be blessed").

Traditional Eritrean attire is quite varied among the ethnic groups of Eritrea. In the larger cities, most people dress in Western casual dress such as jeans and shirts. In offices, both men and women often dress in suits. A common traditional clothing for Christian Tigrinya highlanders consists of bright white gowns called zurias for the women, and a white shirt accompanied by white pants for the men. In Muslim communities in the Eritrean lowlands, the women traditionally dress in brightly colored clothes. Besides convergent culinary tastes, Eritreans share an appreciation for similar music and lyrics, jewelry and fragrances, and tapestry and fabrics, as many other populations in the region.[253]

UNESCO World Heritage Site

On 8 July 2017, the entire capital city of Asmara was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, with the inscription taking place during the 41st World Heritage Committee Session.

The city has thousands of Art Deco, futurist, modernist, and rationalist buildings, constructed during the period of Italian Eritrea.[254][255][256][257][258][259] Asmara, a small town in the nineteenth century, started to grow quickly during 1889.[260] The city also became a place "to experiment with radical new designs", mainly futuristic and art deco inspired.[261] Even though city planners, architects, and engineers were largely European, members of the indigenous population were largely used as construction workers, Asmarinos still identify with their city's legacy.[262]

The city shows off most early twentieth-century architectural styles. Some buildings are neo-Romanesque, such as the Church of Our Lady of the Rosary. Art Deco influences are found throughout the city. Essences of Cubism may be found on the Africa Pension Building and on a small collection of buildings. The Fiat Tagliero Building shows almost the height of futurism, just as it was becoming fashionable in Italy. In recent times, some buildings have been functionally built, which sometimes can spoil the atmosphere of some cities, but they fit into Asmara as it is such a modern city.

Many buildings such as opera houses, hotels, and cinemas were built during this period. Some notable buildings include the Art Deco Cinema Impero (opened in 1937 and considered by the experts one of the world's finest examples of Art Déco style building[263]), Cubist Africa Pension, eclectic Eritrean Orthodox Enda Mariam Cathedral and Asmara Opera, the futurist Fiat Tagliero Building, the neoclassical Asmara city hall.

A statement from UNESCO read:

It is an exceptional example of early modernist urbanism at the beginning of the 20th century and its application in an African context.

Music

Eritrea's ethnic groups each have their distinct styles of music and accompanying dances. Amongst the Tigrinya, the best-known traditional musical genre is the guaila. Traditional instruments of Eritrean folk music include the strung krar, kebero, begena, masenqo, and the wata (a distant/rudimentary cousin of the violin). A popular Eritrean artist is the Tigrinya singer Helen Meles, who is noted for her powerful voice and wide singing range.[264] Other prominent local musicians include the Kunama singer Dehab Faytinga, Ruth Abraha, Bereket Mengisteab, the late Yemane Ghebremichael and the late Abraham Afewerki.

Dancing plays an important role in Eritrean society. The nine ethnic groups have many exuberant dances.[265] The dancing styles differ amongst the ethnic groups; for instance the Bilen and Tigre ethnicities shake their shoulders, while standing rotating in a circle towards the end of the dance, which differs from the Tigrinya who first dance rotating anti-clockwise but later change it to fast-paced dancing and at the same breaking the circular rotation. Kunama ethnic group have dances that include rituals, these are - "tuka (rites of passage); indoda (prayers for rain); sangga-nena (peaceful mediation); and shatta (showcases of endurance and courage)". They are often fast-paced in their character and are accompanied by drum beats.[265]

Media

There are no current independent mass media in Eritrea. All media outlets in Eritrea are from the Ministry of Information, a government source.

Cuisine

A typical traditional Eritrean dish consists of injera accompanied by a spicy stew, which frequently includes beef, chicken, lamb, or fish.[266] Overall, Eritrean cuisine strongly resembles that of neighboring Ethiopia,[266][267] though Eritrean cooking tends to feature more seafood than Ethiopian cuisine on account of their coastal location.[266] Eritrean dishes are also frequently "lighter" in texture than Ethiopian meals. They likewise tend to employ less seasoned butter and spices and more tomatoes, as in the tsebhi dorho delicacy.

Additionally, owing to its colonial history, cuisine in Eritrea features more Italian influences than are present in Ethiopian cooking, including more pasta and greater use of curry powders and cumin. Italian Eritrean cuisine started to be practiced during the colonial times of the Kingdom of Italy, when a large number of Italians moved to Eritrea. They brought the use of pasta to Italian Eritrea, and it is one of the main foods eaten in present-day Asmara. An Italian Eritrean cuisine emerged, and common dishes are "pasta al sugo e berbere" (pasta with tomato sauce and berbere spice), lasagna, and "cotoletta alla Milanese" (veal Milanese).[268]

In addition to coffee, local alcoholic beverages are enjoyed. These include sowa, a bitter drink made from fermented barley, and mies, a fermented honey wine.[269]

Sport

Football and cycling are the most popular sports in Eritrea.[270][271]

Cycling has a long tradition in Eritrea and was first introduced during the colonial period.[272][273] The Tour of Eritrea, a multi-stage cycling event, was first held in 1946 and most recently held in 2017.

The national cycling teams of both men and women are ranked first on the African continent,[277] with the men's team ranked 16th in the world as of February 2023.[278] The Eritrean national cycling team has experienced much success, winning the African Continental cycling championship several years in a row. In 2013, the women's team won the gold medal in the African Continental Cycling Championships for the first time, and for the second time in 2015 and third time in 2019. The men's team has won gold eight times in the last 12 years in the African Continental cycling championships, between 2010 and 2022.[279][280][281][282]

Eritrea has more than 500 elite cyclist riders (men and women) within the country.[283] More than 20 Eritrean riders from Eritrea have signed professional contracts to international cycling teams[citation needed] Daniel Teklehaimanot and Merhawi Kudus became the first cyclists from Africa to compete in the Tour de France in the 2015 edition of the race.[284][285] In 2022, Biniam Girmay was the first African rider to win both the Gent-Wevelgem and a stage in one of the Grand Tours during Giro d'Italia. Multiple African female champion Mosana Debesay became the first African female cyclist to compete in an Olympics, representing Eritrea in the Tokyo 2020 Summer Olympics[286][287] All these accomplishments from Eritrean cyclists, have helped push Eritrea into the top of global rankings in cycling.

Eritrean athletes have also seen increasing success in the international arena in other sports. Zersenay Tadese, an Eritrean athlete, formerly held the world record in the half marathon.[288] Ghirmay Ghebreslassie became the first Eritrean to win a gold medal at a World Championships in Athletics for his country when he took the marathon at the 2015 World Championships.[289] Eritrea made its Winter Olympic debut 25 February 2018, when they competed at the 2018 Winter Olympics in Pyeongchang, South Korea 2018. Eritrea's team was represented by their flagbearer Shannon-Ogbnai Abeda who competed as alpine skier.[290]

Neither the Eritrean national men or women's national football team currently have a world ranking despite being a member association of global governing body FIFA.[291]

See also

References

- ^ a b "Constitution of the State of Eritrea". Shaebia.org. Archived from the original on 3 May 2011. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ a b "Eritrea at a Glance". Eritrea Ministry of Information. 1 October 2009. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ^ "Eritrea", The World Factbook, Central Intelligence Agency, 23 September 2022, retrieved 1 April 2024

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b "Report of the commission of inquiry on human rights in Eritrea". UNHRC website. 8 June 2015. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- ^ "Eritrea: Events of 2016". Human Rights Watch. 12 January 2017.

- ^ a b Saad, Asma (21 February 2018). "Eritrea's Silent Totalitarianism".

- ^ Keane, Fergal (10 July 2018). "Making peace with 'Africa's North Korea'". BBC News.

- ^ Taylor, Adam (12 June 2015). "The brutal dictatorship the world keeps ignoring". The Washington Post. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- ^ a b "Eritrea". Central Intelligence Agency. 27 February 2023. Archived from the original on 10 January 2021. Retrieved 24 February 2023 – via CIA.gov.

- ^ a b "Eritrea country profile". BBC News. 10 May 2011. Archived from the original on 20 November 2023. Retrieved 20 November 2023.

- ^ Human Development Report 2020 The Next Frontier: Human Development and the Anthropocene (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 15 December 2020. pp. 343–346. ISBN 978-92-1-126442-5. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- ^ a b "World Population Prospects 2019". UN DESA. 2019. Archived from the original on 27 February 2021. Retrieved 28 February 2021.

- ^ a b "Eritrea – Indicators – Population (million people), 2018". Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa. 2019. Archived from the original on 28 February 2021. Retrieved 28 February 2021.

- ^ a b "Eritrea – Population and Health Survey 2010" (PDF). National Statistics Office, Fafo Institute for Applied International Studies. 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 June 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

- ^ a b c d "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2023 Edition. (Eritrea)". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. 10 October 2023. Retrieved 12 October 2023.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2023/2024". United Nations Development Programme. 19 March 2024. Retrieved 19 March 2024.

- ^ "Eritrea". Dictionary.com Unabridged (Online). n.d.

- ^ "Eritrea". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ "Name change for Eritrea and other minor corrections" (PDF). International Organization for Standardization. 2 August 2012. Retrieved 5 May 2024.

- ^ a b Munro-Hay, Stuart (1991). Aksum: An African Civilization of Late Antiquity (PDF). Edinburgh: University Press. p. 57. ISBN 0-7486-0106-6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 January 2013. Retrieved 24 June 2012.

- ^ a b Henze, Paul B. (2005) Layers of Time: A History of Ethiopia, ISBN 1-85065-522-7.

- ^ Aksumite Ethiopia. Workmall.com (24 March 2007). Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ^ a b c "Encyclopedia Britannica". www.britannica.com. 18 March 2024.

- ^ "EASO Country of Origin Information Report: Eritrea Country Focus" (PDF). European Asylum Support Office. May 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 June 2021. Retrieved 19 August 2021.

- ^ "National Unity: Eritrea's core value for peace and stability".

- ^ "Eritrea at a Glance".

- ^ "Eritrea Constitution" (PDF). UNESCO. Retrieved 19 August 2021.

- ^ a b c "Eritrea". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. 22 September 2021.

- ^ a b "Eritrea". Grassroots International. Archived from the original on 24 July 2008. Retrieved 24 July 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b Eritrea Human Rights Overview. Human Rights Watch (2006)

- ^ "Human Rights and Eritrea's Reality" (PDF). E Smart. E Smart Campaign. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 August 2014. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ^ "Eritrea: A dictatorship in which the media have no rights". Reporters Without Borders. Retrieved 13 March 2023.

- ^ a b "Arab League Fast Facts". CNN. 18 March 2016. Retrieved 5 June 2016.

- ^ Dan Connell; Tom Killion (14 October 2010). Historical Dictionary of Eritrea. Scarecrow Press. pp. 7–. ISBN 978-0-8108-7505-0.

- ^ "Today, 23 May 1997, on this historic date, after active popular participation, approve and solemnly ratify, through the Constituent Assembly, this Constitution as the fundamental law of our Sovereign and Independent State of Eritrea." The Constitution of Eritrea (eritrean-embassy.se) Archived 4 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ McGraw-Hill Encyclopedia of Science and Technology (9th ed.). The McGraw Hill Companies Inc. 2002. ISBN 978-0-07-913665-7.

- ^ Chang, Gloria (8 September 1999). "Pleistocene Park". Hunting Hominids. Discovery Channel Canada. Archived from the original on 13 October 1999. Retrieved 2 October 2006.

- ^ a b Walter, R. C.; Buffler, R. T.; Bruggemann, J. H.; Guillaume, M. M. M.; Berhe, S. M.; Negassi, B.; Libsekal, Y.; Cheng, H.; Edwards, R. L.; Von Cosel, R.; Néraudeau, D.; Gagnon, M. (2000). "Early human occupation of the Red Sea coast of Eritrea during the last interglacial". Nature. 405 (6782): 65–69. Bibcode:2000Natur.405...65W. doi:10.1038/35011048. PMID 10811218. S2CID 4417823.

- ^ "Out of Africa". 10 September 1999. Archived from the original on 28 September 2006. Retrieved 2 October 2006.

- ^ Zarins, Juris (1990). "Early Pastoral Nomadism and the Settlement of Lower Mesopotamia". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. 280 (280): 31–65. doi:10.2307/1357309. JSTOR 1357309. S2CID 163491760.

- ^ Diamond, J.; Bellwood, P. (2003). "Farmers and Their Languages: The First Expansions". Science. 300 (5619): 597–603. Bibcode:2003Sci...300..597D. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1013.4523. doi:10.1126/science.1078208. PMID 12714734. S2CID 13350469.

- ^ Blench, R. (2006). Archaeology, Language, and the African Past. Rowman Altamira. pp. 143–144. ISBN 978-0-7591-0466-2.

- ^ Connell, Dan (24 May 2002). "Eritrea: A Country Handbook". Ministry of Information – via Google Books.

- ^ G, Mussie Tesfagiorgis (24 May 2010). Eritrea. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-231-9 – via Google Books.