Horse gait

Horses can use various gaits (patterns of leg movement) during locomotion across solid ground, either naturally or as a result of specialized training by humans.[1]

Classification

[edit]Gaits are typically categorized into two groups: the "natural" gaits that most horses will use without special training, and the "ambling" gaits that are various smooth-riding, four-beat footfall patterns that may appear naturally in some individuals. Special training is often required before a horse will perform an ambling gait in response to a rider's command.[1]

Another system of classification that applies to quadrupeds uses three categories: walking and ambling gaits, running or trotting gaits, and leaping gaits.[2] The British Horse Society dressage rules require competitors to perform four variations of the walk, six forms of the trot, five leaping gaits (all forms of the canter), halt, and rein back, but not the gallop.[2] The British Horse Society equitation examinations also require proficiency in the gallop as distinct from the canter.[3][4]

The so-called "natural" gaits, in increasing order of speed, are the walk, trot, canter, and gallop.[5] Some consider these as three gaits, with the canter a variation of the gallop. All four gaits are seen in wild horse populations. While other intermediate speed gaits may occur naturally to some horses, these four basic gaits occur in nature across almost all horse breeds.[1] In some animals the trot is replaced by the pace or an ambling gait.[5] Horses who possess an ambling gait are usually also able to trot.

Walk

[edit]

The walk is a four-beat gait that averages about 7 kilometres per hour (4.3 mph). When walking, a horse's legs follow this sequence: left hind leg, left front leg, right hind leg, right front leg, in a regular 1-2-3-4 beat. At the walk, the horse will alternate between having three or two feet on the ground. A horse moves its head and neck in a slight up and down motion that helps maintain balance.[6]

In detail, a horse starts a walk by lifting its left front leg (the other three feet are touching the ground). It then lifts its right hind leg (while being supported by the diagonal pair right front and left hind). Next, the left front foot touches the ground (the horse is now supported by all but the right hind leg); then the horse lifts its right front leg (it is now supported laterally on both left legs), and shortly afterwards it sets down the right hind leg (only the right front leg is now lifted). Then it lifts its left hind leg (diagonal support), puts down the right front (lateral support), lifts the left front, puts down the left hind, and the pattern repeats.

Ideally, the advancing rear hoof oversteps the spot where the previously advancing front hoof touched the ground. The more the rear hoof oversteps, the smoother and more comfortable the walk becomes. Individual horses and different breeds vary in the smoothness of their walk. However, a rider will almost always feel some degree of gentle side-to-side motion in the horse's hips as each hind leg reaches forward.

The fastest "walks" with a four-beat footfall pattern are actually the lateral forms of ambling gaits such as the running walk, singlefoot, and similar rapid but smooth intermediate speed gaits. If a horse begins to speed up and lose a regular four-beat cadence to its gait, the horse is no longer walking but is beginning to either trot or pace.

Trot

[edit]

The trot is a two-beat gait that has a wide variation in possible speeds and averages about 13 kilometres per hour (8.1 mph). A very slow trot is sometimes referred to as a jog. An extremely fast trot has no special name, but in harness racing, the trot of a Standardbred is faster than the gallop of the average non-racehorse.[7] The North American speed record for a racing trot under saddle was measured at 48.68 kilometres per hour (30.25 mph)[8]

In this gait, the horse moves its legs in unison in diagonal pairs. From the standpoint of the balance of the horse, this is a very stable gait, and the horse need not make major balancing motions with its head and neck.[7] The trot is the working gait for a horse. Horses can only canter and gallop for short periods at a time, after which they need time to rest and recover. Horses in good condition can maintain a working trot for hours. The trot is the main way horses travel quickly from one place to the next.[citation needed]

Depending on the horse and its speed, a trot can make it difficult for a rider to sit because the body of the horse drops a bit between beats and bounces up again when the next set of legs strike the ground. Each time another diagonal pair of legs hits the ground, the rider can be jolted upwards out of the saddle and meet the horse with some force on the way back down. Therefore, at most speeds above a jog, especially in English riding disciplines, most riders post to the trot, rising up and down in rhythm with the horse to avoid being jolted. Posting is easy on the horse's back and once mastered is also easy on the rider.[7]

To not be jostled out of the saddle or harm the horse by bouncing on its back, riders must learn specific skills in order to "sit" the trot. Most riders can easily learn to sit a slow jog trot without bouncing. A skilled rider can ride even a powerfully extended trot without bouncing, but to do so requires well-conditioned back and abdominal muscles, and to do so for long periods is tiring for even experienced riders. A fast, uncollected, racing trot, such as that of the harness racing horse, is virtually impossible to sit.

Because the trot is such a safe and efficient gait for a horse, learning to ride the trot correctly is an important component in almost all equestrian disciplines. Nonetheless, "gaited" or "ambling" horses that possess smooth four-beat intermediate gaits that replace or supplement the trot (see "ambling gaits" below) are popular with riders who prefer for various reasons not to have to ride at a trot.

Two variations of the trot are specially trained in advanced dressage horses: the piaffe and the passage. The piaffe is essentially created by asking the horse to trot in place, with very little forward motion. The passage is an exaggerated slow-motion trot. Both require tremendous collection, careful training, and considerable physical conditioning for a horse to perform them.[9]

Canter (Lope)

[edit]

The canter, or Lope as it is known in Western circles of riding, is a controlled three-beat gait that is usually a bit faster than the average trot but slower than the gallop. The average speed of a canter is 16–27 km/h (10–17 mph), depending on the length of the stride of the horse. Listening to a horse canter, one can usually hear the three beats as though a drum had been struck three times in succession. Then there is a rest, and immediately afterwards the three-beat occurs again. The faster the horse is moving, the longer the suspension time between the three beats.[10] The word is thought to be short for "Canterbury gallop".[11]

In the canter, one of the horse's rear legs – the right hind leg, for example – propels the horse forward. During this beat, the horse is supported only on that single leg while the remaining three legs are moving forward. On the next beat the horse catches itself on the left hind and right front legs while the other hind leg is still momentarily on the ground. On the third beat, the horse catches itself on the left front leg while the diagonal pair is momentarily still in contact with the ground.[10]

The more extended foreleg is matched by a slightly more extended hind leg on the same side. This is referred to as a "lead". Except in special cases, such as the counter-canter, it is desirable for a horse to lead with its inside legs when on a circle. Therefore, a horse that begins cantering with the right hind leg as described above will have the left front and hind legs each land farther forward. This would be referred to as being on the "left lead".[10]

When a rider is added to the horse's natural balance, the question of the lead becomes more important. When riding in an enclosed area such as an arena, the correct lead provides the horse with better balance. The rider typically signals the horse which lead to take when moving from a slower gait into the canter. In addition, when jumping over fences, the rider typically signals the horse to land on the correct lead to approach the next fence or turn. The rider can also request the horse to deliberately take up the wrong lead (counter-canter), a move required in some dressage competitions and routine in polo, which requires a degree of collection and balance in the horse. The switch from one lead to another without breaking gait is called the "flying lead change" or "flying change". This switch is also a feature of dressage and reining schooling and competition.

If a horse is leading with one front foot but the opposite hind foot, it produces an awkward rolling movement, called a cross-canter, disunited canter or "cross-firing".

Gallop

[edit]

The gallop is very much like the canter, except that it is faster, more ground-covering, and the three-beat canter changes to a four-beat gait. It is the fastest gait of the horse, averaging about 40 to 48 kilometres per hour (25 to 30 mph), and in the wild is used when the animal needs to flee from predators or simply cover short distances quickly. Horses seldom will gallop more than 1.5 to 3 kilometres (0.9 to 2 mi) before they need to rest, though horses can sustain a moderately paced gallop for longer distances before they become winded and have to slow down.[12]

The gallop is the gait of the classic race horse. Modern Thoroughbred horse races are seldom longer than 1.5 miles (2.4 km), though in some countries Arabian horses are sometimes raced as far as 2.5 miles (4.0 km). The fastest galloping speed is achieved by the American Quarter Horse, which in a short sprint of a quarter mile (0.25 miles (0.40 km)) or less has been clocked at speeds approaching 55 miles per hour (88.5 km/h).[13] The Guinness Book of World Records lists a Thoroughbred as having averaged 43.97 miles per hour (70.76 km/h) over a two-furlong (0.25 miles (402 m)) distance in 2008.[14]

Like a canter, the horse will strike off with its non-leading hind foot; but the second stage of the canter becomes, in the gallop, the second and third stages because the inside hind foot hits the ground a split second before the outside front foot. Then both gaits end with the striking off of the leading leg, followed by a moment of suspension when all four feet are off the ground. A careful listener or observer can tell an extended canter from a gallop by the presence of the fourth beat.[12]

Contrary to the old "classic" paintings of running horses, which showed all four legs stretched out in the suspension phase, when the legs are stretched out, at least one foot is still in contact with the ground. When all four feet are off the ground in the suspension phase of the gallop, the legs are bent rather than extended. In 1877, Leland Stanford settled an argument about whether racehorses were ever fully airborne: he paid photographer Eadweard Muybridge to prove it photographically. The resulting photos, known as The Horse in Motion, are the first documented example of high-speed photography and they clearly show the horse airborne.

According to Equix, who analyzed the biometrics of racing Thoroughbreds, the average racing colt has a stride length of 24.6 feet (7.5 m); that of Secretariat, for instance, was 24.8 feet (7.6 m), which was probably part of his success.

A controlled gallop used to show a horse's ground-covering stride in horse show competition is called a "gallop in hand" or a hand gallop.[12]

In complete contrast to the suspended phase of a gallop, when a horse jumps over a fence, the legs are stretched out while in the air, and the front legs hit the ground before the hind legs. Essentially, the horse takes the first two steps of a galloping stride on the take-off side of the fence, and the other two steps on the landing side. A horse has to collect its hindquarters after a jump to strike off into the next stride.[15]

Pace

[edit]

The pace is a lateral two-beat gait. In the pace, the two legs on the same side of the horse move forward together, unlike the trot, where the two legs diagonally opposite from each other move forward together. In both the pace and the trot, two feet are always off the ground. The trot is much more common, but some horses, particularly in breeds bred for harness racing, naturally prefer to pace. Pacers are also faster than trotters on average, though horses are raced at both gaits. Among Standardbred horses, pacers breed truer than trotters – that is, trotting sires have a higher proportion of pacers among their get than pacing sires do of trotters.[16]

A slow pace can be relatively comfortable, as the rider is lightly rocked from side to side. A slightly uneven pace that is somewhat between a pace and an amble is the sobreandando of the Peruvian Paso. On the other hand, a slow pace is considered undesirable in an Icelandic horse, where it is called a lull or a "piggy-pace".

With one exception, a fast pace is uncomfortable for riding and very difficult to sit, because the rider is moved rapidly from side to side. The motion feels somewhat as if the rider is on a camel, another animal that naturally paces. However, a camel is much taller than a horse and so even at relatively fast speeds, a rider can follow the rocking motion of a camel. A pacing horse, being smaller and taking quicker steps, moves from side to side at a rate that becomes difficult for a rider to follow at speed, so though the gait is faster and useful for harness racing, it becomes impractical as a gait for riding at speed over long distances. However, in the case of the Icelandic horse, where the pace is known as the skeið, "flying pace" or flugskeið, it is a smooth and highly valued gait, ridden in short bursts at great speed.

A horse that paces and is not used in harness is often taught to perform some form of amble, obtained by lightly unbalancing the horse so the footfalls of the pace break up into a four beat lateral gait that is smoother to ride. A rider cannot properly post to a pacing horse because there is no diagonal gait pattern to follow, though some riders attempt to avoid jostling by rhythmically rising and sitting.

Based on studies of the Icelandic horse, it is possible that the pace may be heritable and linked to a single genetic mutation on DMRT3 in the same manner as the lateral ambling gaits.[17]

Ambling

[edit]There are a significant number of names for various four-beat intermediate gaits. Though these names derive from differences in footfall patterns and speed, historically they were once grouped together and collectively referred to as the "amble". In the United States, horses that are able to amble are referred to as "gaited".[18] In almost all cases, the primary feature of the ambling gaits is that one of the feet is bearing full weight at any one time, reflected in the colloquial term, "singlefoot".

All ambling gaits are faster than a walk but usually slower than a canter. They are smoother for a rider than either a trot or a pace, and most can be sustained for relatively long periods, making them particularly desirable for trail riding and other tasks where a rider must spend long periods of time in the saddle. There are two basic types: lateral, wherein the front and hind feet on the same side move in sequence, and diagonal, where the front and hind feet on opposite sides move in sequence.[19] Ambling gaits are further distinguished by whether the footfall rhythm is isochronous (four equal beats in a 1–2–3–4 rhythm) or non-isochronous (1–2, 3–4 rhythm) created by a slight pause between the ground strike of the forefoot of one side to the hind foot of the other.

Not all horses can perform an ambling gait. However, many breeds can be trained to produce them. In most "gaited" breeds, an ambling gait is a hereditary trait. A 2012 DNA study of movement in Icelandic horses and mice have determined that a mutation on the gene DMRT3, which is related to limb movement and motion, causes a premature "stop codon" in horses with lateral ambling gaits.[20][17]

The major ambling gaits include:

- The fox trot is most often associated with the Missouri Fox Trotter breed, but it is also seen under different names in other gaited breeds. The fox trot is a four-beat diagonal gait in which the front foot of the diagonal pair lands before the hind.[21] The same footfall pattern is characteristic of the trocha, pasitrote and marcha batida seen in various South American breeds.

- Many South American horse breeds have a range of smooth intermediate lateral ambling gaits. The Paso Fino's speed variations are called (from slowest to fastest) the paso fino, paso corto, and paso largo. The Peruvian Paso's lateral gaits are known as the paso llano[18] and sobreandando. The lateral gait of the Mangalarga Marchador is called the marcha picada.

- The rack or racking is a lateral gait most commonly associated with the five-gaited American Saddlebred. In the rack, the speed is increased to be approximately that of the pace, but it is a four-beat gait with equal intervals between each beat.[18]

- The running walk, a four-beat lateral gait with footfalls in the same sequence as the regular walk but characterized by greater speed and smoothness. It is a distinctive natural gait of the Tennessee Walking Horse.[18]

- The slow gait is a general term for various lateral gaits that follow the same general lateral footfall pattern, but the rhythm and collection of the movements are different. Terms for various slow gaits include the stepping pace and singlefoot.[18]

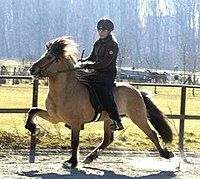

- The tölt is a gait that is often described as being unique to the Icelandic horse. The footfall pattern is the same as for the rack, but the tölt is characterized by more freedom and liquidity of movement. Some breeds of horses that are related to the Icelandic horse, living in the Faroe Islands and Norway, also tölt.[18]

- The revaal or ravaal is a four-beat lateral gait associated with Marwari, Kathiawari or Sindhi horse breeds of India.

-

Icelandic horse at the tölt

-

Tennessee Walking Horse at the running walk

-

Saddlebred performing the rack

Notes and references

[edit]- ^ a b c Ensminger, M. E. Horses and Horsemanship 6th edition USA: Interstate Publishers 1990 ISBN 0-8134-2883-1 pp. 65–66

- ^ a b Tristan David Martin Roberts (1995) Understanding Balance: The Mechanics of Posture and Locomotion, Nelson Thornes, ISBN 0-412-60160-5

- ^ "Junior Equitation and Horse Welfare 2A requires riders to 'be able to develop a hand gallop from a canter and return smoothly to canter". www.bhs.org.uk.

- ^ "Junior Equitation and Horse Welfare 3A requires riders to 'maintain a balanced and secure position at walk, trot (sitting and rising), canter and gallop, showing the rider is progressing along the right lines". www.bhs.org.uk.

- ^ a b Harris, Susan E. Horse Gaits, Balance and Movement New York: Howell Book House 1993 ISBN 0-87605-955-8 p. 32

- ^ Harris, Susan E. Horse Gaits, Balance and Movement New York: Howell Book House 1993 ISBN 0-87605-955-8 pp. 32–33

- ^ a b c Harris, Susan E. Horse Gaits, Balance and Movement New York: Howell Book House 1993 ISBN 0-87605-955-8 pp. 35–37

- ^ "Chantal Rides Trotter to North American Record – Horse Racing News – Paulick Report". www.paulickreport.com. 23 September 2013.

- ^ Harris, Susan E. Horse Gaits, Balance and Movement New York: Howell Book House 1993 ISBN 0-87605-955-8 p. 39

- ^ a b c Harris, Susan E. Horse Gaits, Balance and Movement New York: Howell Book House 1993 ISBN 0-87605-955-8 pp. 42–44

- ^ "Online Etymology Dictionary". www.etymonline.com.

- ^ a b c Harris, Susan E. Horse Gaits, Balance and Movement New York: Howell Book House 1993 ISBN 0-87605-955-8 pp. 47–49

- ^ "American Quarter Horse-Racing Basics". America's Horse Daily. American Quarter Horse Association. May 26, 2014. Archived from the original on March 9, 2016. Retrieved 2016-03-09.

- ^ "Fastest speed for a race horse". Guinness World Records. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

- ^ Harris, Susan E. Horse Gaits, Balance and Movement New York: Howell Book House 1993 ISBN 0-87605-955-8 pp. 57–63

- ^ Harris, Susan E. Horse Gaits, Balance and Movement New York: Howell Book House 1993 ISBN 0-87605-955-8 p. 50

- ^ a b Andersson, Lisa S; et al. (30 August 2012). "Mutations in DMRT3 affect locomotion in horses and spinal circuit function in mice". Nature. 488 (7413): 642–646. Bibcode:2012Natur.488..642A. doi:10.1038/nature11399. PMC 3523687. PMID 22932389.

- ^ a b c d e f Harris, Susan E. Horse Gaits, Balance and Movement New York: Howell Book House 1993 ISBN 0-87605-955-8 pp. 50–55

- ^ Lieberman, Bobbie. "Easy-Gaited Horses". Equus, issue 359, August, 2007, pp. 47–51.

- ^ Agricultural Communications, Texas A&M University System (5 September 2012). "'Gaited' Gene Mutation and Related Motion Examined". The Horse. Blood-Horse Publications. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- ^ Ensminger, M. E. Horses and Horsemanship 6th edition USA: Interstate Publishers 1990 ISBN 0-8134-2883-1 p. 68

External links

[edit]- Photographs of various horse traits, by Eadweard Muybridge, Animals in Motion

- Gaits of the Horse[usurped]

- Animations of the gaits of the Icelandic horse

- Map detailing the relationship between the gaits of the Icelandic horse

- Equix: Bluegrass Thoroughbred Services, Greenfield Farm – videos of walking gaits of various racehorses

- Natural Gaits of the Horse from eXtension Archived 2010-04-13 at the Wayback Machine