Egyptian Museum

المتحف المصري | |

| |

| |

| |

| Established | 1902 |

|---|---|

| Location | Cairo, Egypt |

| Coordinates | 30°02′52″N 31°14′00″E / 30.047778°N 31.233333°E |

| Type | History museum |

| Collection size | 120,000 items |

| Director | Sabah Abdel-Razek |

| Architect | Marcel Dourgnon |

| Website | www |

The Museum of Egyptian Antiquities, commonly known as the Egyptian Museum (Arabic: المتحف المصري, romanized: al-Matḥaf al-Miṣrī, Egyptian Arabic: el-Matḥaf el-Maṣri [elˈmætħæf elˈmɑsˤɾi]) (also called the Cairo Museum), located in Cairo, Egypt, houses the largest collection of Egyptian antiquities in the world.[1] It houses over 120,000 items, with a representative amount on display. Located in Tahrir Square in a building built in 1901, it is the largest museum in Africa. Among its masterpieces are Pharaoh Tutankhamun's treasure, including its iconic gold burial mask, widely considered one of the best-known works of art in the world and a prominent symbol of ancient Egypt.[2]

History

[edit]

The Egyptian Museum of Antiquities contains many important pieces of ancient Egyptian history. It houses the world's largest collection of Pharaonic antiquities. The Egyptian government established the museum built in 1835 near the Ezbekieh Garden and later moved to the Cairo Citadel. In 1855, Archduke Maximilian of Austria was given all of the artifacts by the Egyptian government; these are now in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.

A new museum was established at Boulaq in 1858 in a former warehouse, following the foundation of the new Antiquities Department under the direction of Auguste Mariette. The building lay on the bank of the Nile River, and in 1878 it suffered significant damage owing to the flooding of the Nile River. In 1891, the collections were moved to a former royal palace, in the Giza district of Cairo.[3] They remained there until 1902 when they were moved again to the current museum in Tahrir Square, built by the Italian company of Giuseppe Garozzo and Francesco Zaffrani to a design by the French architect Marcel Dourgnon.[4]

The bigger part of the museum's garden that stretched until the Nile was taken away in 1954 to build the Cairo Municipality Building.[5]

In 2004, the museum appointed Wafaa El Saddik as the first female director general.[6]

During the Egyptian Revolution of 2011, the museum was broken into, and two mummies were destroyed.[7][8] Several artifacts were also shown to have been damaged and around 50 objects were stolen.[9][10] Since then, 25 objects have been found. Those that were restored were put on display in September 2013 in an exhibition entitled "Damaged and Restored". Among the displayed artifacts were two statues of King Tutankhamun made of cedar wood and covered with gold, a statue of King Akhenaten, ushabti statues that belonged to the Nubian kings, a mummy of a child, and a small polychrome glass vase.[11]

The museum was reportedly used as a torture site during the 2011 Revolution, with protestors forcibly and unlawfully detained and allegedly abused, according to reports, videos and eyewitness accounts.[12] Activists state that "men were being tortured with electric shocks, whips and wires," and "women were tied to fences and trees." Prominent singer and activist Ramy Essam was among those detained and tortured at the museum.[13]

Youssef Diaa Effendi, the Director of the Antiquities Department, began inspecting the antiquities of Middle Egypt shortly after assuming his position, focusing on those discovered by farmers. In 1848, Muhammad Ali Pasha assigned Linan Bek, the Minister of Education, to compile a comprehensive report on archaeological sites and send artifacts to the Egyptian Museum. However, this effort was not successful due to the death of Muhammad Ali Pasha in 1849, followed by a period of instability. The trade in antiquities resurfaced, and the collection housed in the museum established in Azbakeya began to shrink until it was transferred to a single hall in the Citadel of Saladin. The situation worsened when Khedive Abbas I donated the entire contents of this hall to Duke Maximilian of Austria during his visit to the citadel.

Mariette considered the Boulaq Museum a temporary location, and after the flood incident, he saw an opportunity to advocate for the establishment of a permanent museum with greater capacity to accommodate a larger collection of artifacts, while also being situated away from the flood path. After Mariette's death, he was succeeded by Gaston Maspero, who attempted to move the museum from Boulaq but was unsuccessful. By 1889, the building housing the collections reached its peak of overcrowding, with no available rooms for more artifacts, either in the exhibition halls or storage areas. Artifacts discovered during excavations were often left for long periods in boats in Upper Egypt. This dire situation led Khedive Ismail to offer one of his palaces in Giza, the location of the present-day zoo, to serve as the new museum. Between the summer and the end of 1889, all the artifacts were moved from the Boulaq Museum to Giza, and the artifacts were reorganized in the new museum by the scholar De Morgan, who served as the museum's director. From 1897 to 1899, Loret succeeded De Morgan, but Maspero returned to manage the museum from 1899 to 1914.[14][15]

The current Egyptian Museum

[edit]The architectural design of the museum was created by the French architect Marcel Dournon in 1897, to be located in the northern area of Tahrir Square (formerly Ismailia Square), along the British Army barracks in Cairo near Qasr El-Nil. The foundation stone was laid on April 1, 1897, in the presence of Khedive Abbas Hilmi II, the Prime Minister, and all his cabinet members.[16][17][18] The project was completed by the German architect Hermann Grabe. In November 1903, the Antiquities Department appointed the Italian architect Alessandro Parazenti, who had received the keys to the museum on March 9, 1902, and began the process of transferring the archaeological collections from Khedive Ismail's palace in Giza to the new museum. This operation involved the use of five thousand wooden carts, while large artifacts were transported by two trains, making about nineteen round trips between Giza and Qasr El-Nil. The first shipment carried approximately forty-eight stone coffins, weighing over a thousand tons in total. However, the transportation process was chaotic at times. The transfer was completed by July 13, 1902, and Mariette's tomb was moved to the museum garden in accordance with his wish to be buried among the artifacts he had spent much of his life collecting.

The Egyptian Museum was officially opened on November 15, 1902. The new museum adopted an exhibition style based on a gradual arrangement of halls, without allocating rooms for periods of turmoil, as they were considered historically insignificant. The artifacts in the museum were categorized by their themes, though for architectural reasons, large statues were placed on the ground floor, while funerary items were displayed on the first floor in chronological order. Each day, new artifacts were arranged and displayed according to their themes in various rooms. The museum became the only one in the world so filled with artifacts that it resembled a storage facility. When asked about this, Maspero replied that the Egyptian Museum was a reflection of a pharaonic tomb or temple, where every part of the space was used to display paintings or hieroglyphic inscriptions. Even the modern Egyptian home of that time used every part of the walls for paintings and images, making the museum a representation of both ancient and modern Egypt.[19]

Museum development

[edit]

In 1983, the museum building was registered as a heritage site due to its unique architectural value. In August 2006, the largest development operation was carried out on the museum, aiming to make it a scientific and cultural destination.[20] This included the establishment of a cultural center and an administrative-commercial annex on the western side of the museum, where informal settlements were removed.[21] Due to various architectural distortions the building had suffered over the years, which hid much of its original aesthetic charm due to external factors like pollution and heavy traffic, the Ministry of Antiquities launched an initiative in May 2012 to create a comprehensive rehabilitation plan for the museum. The German Foreign Ministry funded the necessary studies and scientific research, and the International Environmental Quality Association participated in the implementation of the initiative to restore the museum to its original condition. The project included architectural and engineering restoration work, as well as the development of the surrounding area of Tahrir Square. The project was completed by 2016, after restoring the eastern and northern wings, addressing lighting issues, and reorganizing the display of valuable artifacts.

The first phase of the initiative involved sampling the original color of the museum building and restoring the walls to their original color. It also included wall surface restoration, the restoration of decorations on the walls and columns, the replacement of window glass with UV-protective glass to safeguard the artifacts, and the restoration of the original ventilation system after thorough cleaning. Restoration work relied on 257 preserved panels within the museum's library, which displayed the building's original designs.[22][23]

In July 2016, the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities (Egypt) upgraded the museum’s internal and external lighting systems, allowing the museum to be open for nighttime visits. In November 2018, the final phase of the museum’s development was inaugurated, which included a new exhibition scenario, the display of the collections of Yuya and Thuya on the upper floor, as well as the display of King Tutankhamun’s artifacts, until the rest of his collection is moved to the Grand Egyptian Museum. The works also involved repainting the walls, upgrading the outlets, updating the lighting system, and restoring the display cases. These tasks were overseen by a committee that included directors of the world’s largest museums, who contributed to the scientific perspective on redistributing the artifacts after the transfer of the items related to the Grand Egyptian Museum and the Museum of Civilization. The committee included directors from the museums of Turin, the Louvre, United Museums, and Berlin.[24][25]

Museum library

[edit]

The museum library was established at the time of the museum's opening, with funds allocated since 1899 for the purchase of books. The Egyptologist Maspero advocated for a permanent budget for acquiring books and appointed Dacros as the first librarian from 1903 to 1906. He was succeeded by several librarians, including Monier, who compiled a comprehensive catalog of the library’s holdings until 1926. A significant turning point for the library occurred when Abdel Mohsen El-Khashab assumed its management. He was assisted by Diaa El-Din Abu Ghazi, who later became the head librarian in 1950. Abu Ghazi played a crucial role in preparing catalogues, increasing international exchanges, and expanding the library, which eventually grew to its current two-story size with two reading rooms and a storage area for publications.

The library houses over 50,000 books and volumes, including rare works on ancient Egyptian, Greek, Roman, and Near Eastern archaeology, along with other specialized fields. Some of its most significant books include Description de l'Égypte, Antiquités de l'Égypte et de la Nubie, and Lepsius' works. The library also contains a rare collection of maps, paintings, and photographs.[26]

Museum collections

[edit]- Prehistoric Period: This collection includes various types of pottery, jewelry, hunting tools, and everyday life items that represent the products of the ancient Egyptians before the advent of writing. These artifacts reflect the life of early Egyptians who settled in various regions of Egypt, including the north, central, and southern parts of the country.[27][28]

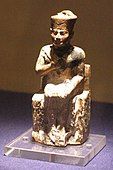

- The Early Dynastic Period: This collection includes artifacts from the First and Second Dynasties, such as the Narmer Palette, the statue of Khasekhemwy, and various vessels and tools.[28][27]

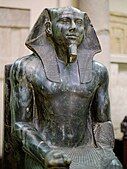

- Old Kingdom Period: This collection includes a range of significant artifacts, such as the statues of Djoser, Khafre, Menkaure, Sheikh El-Balad, the dwarf Seneb, King Pepi I, his son Merenre, as well as numerous coffins, statues of individuals, wall paintings, and the collection of Queen Hetepheres.

- Middle Kingdom Period: This collection includes many significant artifacts, such as the statue of King Montuhotep II, a series of statues of several rulers from the 12th Dynasty, including Senusret I and Amenemhat III, among others. It also features numerous statues of individuals, coffins, jewelry, daily life tools, and fragments of pyramids from the Faiyum region.[28][27]

Tutankhamun's throne chair - New Kingdom Period: This is the most famous collection in the museum, highlighted by the treasures of the young pharaoh Tutankhamun, along with statues of Hatshepsut, Thutmose III, and Ramses II. It also includes chariots, papyri, jewelry, Akhenaten’s collection, the Israel Stele, statues of Amenhotep III and his wife Ti, a variety of amulets, writing tools, and agricultural instruments. Additionally, the Royal Mummy Collection, displayed in a dedicated hall opened in 1994, was a significant feature until the royal mummies were transferred to the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization in Fustat during the Royal Mummy Parade in 2021.

The Tutankhamun Collection - Late Period: This collection features a variety of artifacts, including the treasures of Tanis made from gold, silver, and precious stones, discovered in the tombs of some kings and queens of the 21st and 22nd dynasties at Tanis. It also includes important statues such as the statue of Amun, the statue of Mentuhotep, and the statue of the goddess Tauret, as well as the Canopus Jar Lid (Abu Qir), the stela of Baiankh, and a selection of Nubian artifacts, some of which have been transferred to the Nubian Museum in Aswan.[27][28]

Theft of museum collectibles

[edit]

In August 2004, it was announced that 38 artifacts had disappeared from the museum and could not be located. The incident was referred to the public prosecution for investigation.[29]

During the security turmoil following the January 25 Revolution, the museum was stormed on January 28, 2011, by unidentified individuals, and 54 artifacts were stolen. Zahi Hawass, the then director of the Supreme Council of Antiquities, stated "My heart is broken and my blood is boiling".[30] Hawass later told The New York Times that thieves looking for gold broke 70 objects, including two sculptures of the pharaoh Tutankhamun and took two skulls from a research lab, before being stopped as they left the museum.[31]

In response, the military forces cordoned off the museum to protect and secure it against looting and theft.[32]

Pharaohs' Golden Parade

[edit]On April 3, 2021, the Egyptian Museum witnessed the Pharaohs' Golden Parade, during which 22 royal mummies (18 kings and 4 queens) were transferred from the Egyptian Museum to the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization in Fustat. The mummies are now displayed in state-of-the-art display cases designed to better control temperature and humidity, offering enhanced preservation compared to their previous display in the Egyptian Museum.

Access to the museum and entry

[edit]

The museum is located in the heart of Cairo, on the northern side of Tahrir Square (Downtown). It is accessible by public transportation, private cars with parking available at the multi-story Tahrir parking lot, or the easier option of using the metro, exiting at Sadat Station, which directly overlooks Tahrir Square.[33] The museum is open daily from 9:00 AM to 7:00 PM, with special hours on Fridays from 9:00 AM to 11:00 AM and from 1:30 PM to 7:00 PM.[34][35] Photography is not allowed inside the museum due to the negative effects of camera flashes on the small artifacts' colors. However, personal photography is permitted for a fee of 50 EGP for both Egyptians and foreigners, except in the Hall of the Golden Mask and the Royal Mummy Halls.[36][37] Occasionally, free photography is allowed on specific days to encourage tourism and increase visitors to the museum. Visitors can also rent an audio guide inside the museum for 25 EGP, providing detailed information about the displayed artifacts.[38]

Sale room for antiquities

[edit]The Department of Antiquities (Service d'Antiquités Egyptien) operated a sale room (Salle de ventes) in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo from 1902 in room 56 on the ground floor, where original ancient Egyptian artworks and other original artefacts were sold. In addition, until the 1970s, dealers or collectors could bring antiquities to the Cairo Museum for inspection on Thursdays, and if museum officials had no objections, they could pack them in ready-made boxes, have them sealed and cleared for export. Many objects now held in private collections or public museums originated here. After years of debate about the strategy for selling the antiquities, the sale room was closed in November 1979.[39]

Ticket prices

[edit]The value is in Egyptian pounds.

| Places to visit | Egyptian students and children | Egyptians and Arabs | Foreigners |

|---|---|---|---|

| Morning period | |||

| Museum | 5 | 20 | 120 |

| Hall of Mummies | 20 | 40 | 150 |

| Sunday and Thursday evenings | |||

| Museum | 15 | 30 | 180 |

| Hall of Mummies | 30 | 60 | 225 |

240 EGP is a combined morning ticket for foreigners at a discounted rate for the museum and the Mummies Hall.

Management

[edit]The museum is overseen by the Museums Sector of the Supreme Council of Antiquities, which is part of the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities (Egypt). The management of the museum is entrusted to the position of museum director, a role held by several prominent figures in the field of Egyptology, including:[40]

- Sabah Abdel Razek (September 2016-present).

- Somaya Abdel Samia (March 2016 - September 2016).[41]

- Khaled al-Anani (2015-2016).[42]

- Mahmoud Halougi (2014-2015).[43]

- Sayed Amer (2013-2014).[44]

- Salwa Abdel Rahman (2012-2013).[45]

- Sayed Hassan (2012-2012).[46]

- Tarek al-Awadi (2011-2012).[47]

- Wafaa al-Siddiq (2004-2011).[48]

- Mamdouh Eldamaty (2001-2004).[49]

- Ali Hassan.[50]

- Muhammad Saleh.[51]

- Muhammad Mohsen.[52]

- Diaa al-Din Abu Ghazi.[52]

- Henry Riad.[53]

- Mahmoud Hamza.[54]

- Étienne Drioton (1936-1952).[55]

- Pierre Lacau (1914-1936).[56]

- Gaston Maspero (1899-1914).[57]

- Victor Loret (1897-1899).[58]

- Jacques de Morgan (1892-1897).[58]

- Eugene Grippo (1886-1892).[59]

- Gaston Maspero (1881-1886)

- Auguste Mariette (1858-1881).

Interior design and collections

[edit]

There are two main floors in the museum, the ground floor and the first floor. On the ground floor is an extensive collection of large-scale works in stone including statues, reliefs and architectural elements. These are arranged chronologically in clockwise fashion, from the pre-dynastic to the Greco-Roman period.[60] The first floor is dedicated to smaller works, including papyri, coins, textiles, and an enormous collection of wooden sarcophagi.

The numerous pieces of papyrus are generally small fragments, owing to their decay over the past two millennia. Several languages are found on these pieces, including Greek, Latin, Arabic, and ancient Egyptian. The coins found on this floor are made of many different metals, including gold, silver, and bronze. The coins are not only Egyptian, but also Greek, Roman, and Islamic. This has helped historians research the history of Ancient Egyptian trade.

Also on the ground floor are artifacts from the New Kingdom, the time period between 1550 and 1069 BC. These artifacts are generally larger than items created in earlier centuries. Those items include statues, tables, and coffins (sarcophagi). It contains 42 rooms; with many items on view from sarcophagi and boats to enormous statues.

On the first floor are artifacts from the final two dynasties of Egypt, including items from the tombs of the Pharaohs Thutmosis III, Thutmosis IV, Amenophis II, Hatshepsut, and the courtier Maiherpri, as well as many artifacts from the Valley of the Kings, in particular the material from the intact tombs of Tutankhamun and Psusennes I.

Until 2021, two rooms contained a number of mummies of kings and other royal family members of the New Kingdom. On April 3, 2021, twenty-two of these mummies were transferred to the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization in Fustat in a grand parade dubbed The Pharaohs' Golden Parade.[61]

Collections are also being transferred to the not-yet-open Grand Egyptian Museum in Giza, including all the artifacts found inside Tutankhamun's tomb.[19] "Among the reasons that the GEM itself was conceived, the Egyptian Museum in Tahrir has been criticized for being overcrowded, displaying pieces in a way that is said to make the experience cumbersome for visitors."[19]

Memorial to famous Egyptologists

[edit]In the garden adjacent to the building of the museum, is a memorial to famous egyptologists of the world. It features a monument to Auguste Mariette, surrounded by 24 busts of the following egyptologists: François Chabas, Johannes Dümichen, Conradus Leemans, Charles Wycliffe Goodwin, Emmanuel de Rougé, Samuel Birch, Edward Hincks, Luigi Vassalli, Émile Brugsch, Karl Richard Lepsius, Théodule Devéria, Vladimir Golenishchev, Ippolito Rosellini, Labib Habachi, Sami Gabra, Selim Hassan, Ahmed Kamal, Zakaria Goneim, Jean-François Champollion, Amedeo Peyron, Willem Pleyte, Gaston Maspero, Peter le Page Renouf[62] and Kazimierz Michałowski.

Gallery

[edit]-

The Gold Mask of Tutankhamun, composed of 11 kg of solid gold; since relocated to the Grand Egyptian Museum

-

Mummy mask of Psusennes I

-

Mummy mask of king Amenemope of the 21st dynasty

-

Mummy mask of Shoshenq II of the 22nd dynasty

-

Khufu Statuette, an ivory figurine of Khufu

-

Statue of Menkaure

-

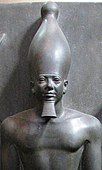

Bust of Akhenaten

-

Statue of Hatshepsut

-

Mummy mask of Wendjebauendjed

-

Rahotep and Nofret (2575-2550 BC)

-

Dwarf Seneb with his wife (2400-2500 BC)

-

Throne of Tutankhamun

-

Wood sculptural composition depicting a cattle census scene (2000 BC)

-

Canopic box from Tutankhamun's tomb

-

Exterior view of the museum

-

Exterior view of the museum

-

Photo of the museum site in 1904

-

Main hall

-

Main hall

-

Amenemhat I in the museum garden

See also

[edit]- Egyptian Museum of Turin

- Egyptian Museum of Berlin

- National Museum of Egyptian Civilization

- Grand Egyptian Museum

- List of largest art museums

- List of museums with major collections of Egyptian antiquities

References

[edit]- ^ "History of the Egyptian Museum – The Egyptian Museum in Cairo". Archived from the original on 27 January 2023. Retrieved 15 February 2023.

- ^ Reeves 2015, p. 522.

- ^ "Supreme Council of Antiquities - Museums". www.sca-egypt.org. Archived from the original on 23 October 2017. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- ^ Kingsley, Patrick (27 January 2015). "Tutankhamun's famous home is undergoing a facelift (no glue involved)". the Guardian. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- ^ حنا, ميشيل (11 August 2018). "حدائق دمرتها دولة يوليو". manassa.news (in Arabic). Retrieved 1 July 2024.

- ^ Düker, Ronald (11 July 2013). "Weltkultur in Gefahr". Die Zeit (in German). Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- ^ "Looters destroy mummies during Egypt protests". ABC News. 29 January 2011. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- ^ "Vandals ravage Egyptian Museum, break mummies". Al-Masry Al-Youm. Archived from the original on 1 February 2011. Retrieved 30 January 2011.

- ^ "Statues of Tutankhamun damaged/stolen from the Egyptian Museum". The Eloquent Peasant. 29 January 2011. Retrieved 30 January 2011.

- ^ "Mummies set on fire as looters raid Egyptian museum - video - Channel 4 News". Channel4.com. 28 August 2013. Retrieved 8 January 2014.

- ^ "Egyptian Museum exhibit puts spotlight on restored artefacts". Daily News Egypt. 23 October 2013. Retrieved 8 January 2014.

- ^ "Egypt's Museums: From Egyptian Museum to 'torture chamber'". Egypt Independent. 20 April 2011. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ رامي عصام - معتصم مش بلطجي, 10 March 2011, retrieved 22 January 2023

- ^ Zahi Hawass (December 7, 2002). "Antiquities and secrets of the Egyptian Museum". Al-Ahram. Archived from the original on 2004-01-09. Accessed on 2015-10-02.

- ^ "The Egyptian Museum. Cairo Governorate. Archived from the original on 2018-10-02. Accessed on 2016-09-05.

- ^ Zahi Hawass (December 7, 2002). "Antiquities and secrets of the Egyptian Museum". Al-Ahram. Archived from the original on 2004-01-09. Accessed on 2015-10-02.

- ^ Mona Salahuddin (May 18, 2003). "Head of Isis crowns the entrance to the Egyptian Museum and the Taliban style characterizes its architecture". Asharq Al-Awsat. Archived from the original on 2018-08-07. Accessed on 2016-09-04.

- ^ Abbas Tarabili (November 16, 2013). "Tale of. The Egyptian Museum!". Al-Wafd. Archived from the original on 2016-09-27. Accessed on 2016-09-05.

- ^ a b c Magazine, Smithsonian; Keyes, Allison. "For the First Time, All 5,000 Objects Found Inside King Tut's Tomb Will Be Displayed Together". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 16 November 2023.

- ^ Amani Abdelhamid (December 29, 2014). "With a budget of ten million euros : The Egyptian Museum gets a new lease on life". Dar al-Hilal. Archived from the original on 2016-09-09. Accessed on 2016-09-06.

- ^ "The largest renovation of the Egyptian Museum, one of the oldest antiquities museums in the world". Al-Sharq Al-Awsat. August 25, 2006. Archived from the original on 2018-08-08. Accessed on 2016-09-04.

- ^ Ahmed Osman (July 11, 2016). "EGP 2 mn to develop the Egyptian Museum's lighting to work at night". Al-Wafd. Archived from the original on 2016-09-27. Accessed on 2016-09-05.

- ^ Ahmed Osman (July 10, 2016). "Antiquities approves EGP 1.6 million contract to develop the Egyptian Museum." The Seventh Day. Archived from the original on 2020-03-05. Accessed on 2016-09-05.

- ^ Ahmed Mansour (July 30, 2018). "Learn about the development plan of the Egyptian Museum in Tahrir ahead of its opening on November 15". Al Youm Al-Sabe'a Archived from the original on 2020-03-05. Accessed on 2018-11-24.

- ^ Razavi Hashem (November 15, 2018). "Minister of Antiquities: Egyptian Museum renovation finished". Al-Watan. Archived from the original on 2018-11-24. Accessed on 2018-11-24.

- ^ "Egyptian Museum's library contains more than 50,000 volumes on Egyptian antiquities". Al-Sharq Al-Awsat. August 15, 2004. Archived from the original on 2018-08-07. Accessed on 2016-09-06.

- ^ a b c d "Egyptian Museum". State Information Service (Egypt). Archived from the original on 2016-08-07. Accessed on 2015-10-02.

- ^ a b c d "The Egyptian Museum. Cairo Governorate. Archived from the original on 2018-10-02. Accessed on 2016-09-05.

- ^ Sahar Zahran (August 5, 2004). "After 38 artifacts disappeared from the Egyptian Museum". Al-Ahram. Archived from the original on 2006-05-05. Accessed on 2016-09-04.

- ^ Lawler, Andrew (2011). "Archaeologists Hold Their Breaths on Status of Egyptian Antiquities" (online). Science. No. January 31. Washington, DC, USA: AAAS. Archived from the original on 19 November 2018. Retrieved 25 January 2016.

The current political upheaval in Egypt has put the country's famed antiquities, from its museums to archaeological sites, under siege. / On 29 January, a small band of looters entered Cairo's Museum of Egyptian Antiquities, slicing the heads from two mummies, smashing display cases, and damaging other artifacts, according to media reports and Zahi Hawass, the director of the Supreme Council of Antiquities. Hawass, who a source says has been promoted to the new position of Minister of Antiquities as part of a cabinet shakeup yesterday, faxed a colleague in Italy that 13 cases were destroyed. "My heart is broken and my blood is boiling," the U.S.-trained archaeologist lamented.

- ^ Taylor, Kate (2011). "Middle East: Antiquities Chief Says Sites Are Largely Secure" (online). The New York Times. No. February 1. Archived from the original on 22 November 2018. Retrieved 25 January 2016.

A vast majority of Egypt's museums and archaeological sites are secure and have not been looted, Zahi Hawass, Egypt's chief antiquities official, said in a telephone interview on Tuesday. He also rejected comparisons between the current situation in Egypt and scenes of chaos and discord that resulted in the destruction of artifacts in Iraq and Afghanistan. / 'People are asking me, "Do you think Egypt will be like Afghanistan?" ' he said. 'And I say, "No, Egyptians are different — they love me because I protect antiquities." '

- ^ Karim Hassan (April 29, 2014). "Minister of Antiquities: 10 rare artifacts stolen from the Egyptian Museum during the January 25 revolution". Al-Ahram. Archived from the original on 2018-08-07. Accessed on 2016-09-05.

- ^ "Cairo City Tourist Guide". Egypt Travels. Archived from the original on 2017-11-16. Accessed on 2016-09-04.

- ^ "The Egyptian Museum. Egyptian Tourism Promotion Authority. Archived from the original on 2016-09-28. Accessed on 2016-09-04.

- ^ Khaled Youssef (July 16, 2015). "Ahead of Eid. Ticket prices for parks and archaeological sites". Dot Masr. Archived from the original on 2016-12-19. Accessed on 2016-09-04.

- ^ Moataz Shams El-Din (January 7, 2016). "Why was photography banned inside the Egyptian Museum?". Huffington Post Arabic. Archived from the original on 2017-10-05. Accessed on 2016-09-04.

- ^ "Antiquities allows personal photography for 50 pounds for Egyptians and foreigners at the Egyptian Museum." Al-Watan. January 29, 2016. Archived from the original on 2018-08-08. Accessed on 2016-09-04.

- ^ "Up to 240 pounds. We publish the new ticket prices for the Egyptian Museum in Tahrir". Masrawy. July 8, 2018. Archived from the original on 2019-02-20. Accessed on 2018-07-27.

- ^ Piacentini, Patrizia (2017). "Notes on the History of the Sale Room of the Egyptian Museum". In Jana Helmbold-Doyé; Thomas L. Gertzen (eds.). Mosse im Museum. Berlin: Hentrich & Hentrich. pp. 75–87. ISBN 978-3955652210.

- ^ Heba Adel (August 23, 2016). "'Antiquities' prepares to light up the Egyptian Museum and the Citadel to open them at night". Al-Ahram. Archived from the original on 2016-09-20. Accessed on 2016-09-04.

- ^ Ahmed Mansour (March 30, 2016). "Soumaya Abdel Samiya assigned to run the Egyptian Museum and Mahrous Said Civilization Museum". Al-Youm Al-Sabea. Archived from the original on 2020-03-05. Accessed on 2016-09-04.

- ^ Ahmed Mansour (October 8, 2015). "Antiquities appoints Khaled El-Enany as general supervisor of the Egyptian Museum". The Seventh Day. Archived from the original on 2020-03-05. Accessed on 2016-09-04.

- ^ "The Egyptian Museum's director says the building is intact and tourism is normal." Al-Shorouk. July 11, 2015. Archived from the original on 2018-08-07. Accessed on 2015-10-05.

- ^ Maged Abdel Qader (June 29, 2013). "Intensified security measures for the Egyptian Museum and the Haram Antiquities Zone during tomorrow's demonstrations". Al-Ahram. Archived from the original on 2018-08-07. Accessed on 2015-10-05.

- ^ "Salwa Abdel Rahman as director of the Egyptian Museum. Al-Watan. December 3, 2012. Archived from the original on 2018-08-08. Accessed on 2016-09-04.

- ^ Dina Abdel Aleem (March 24, 2012). "Sayed Hassan appointed director of the Egyptian Museum, replacing Tarek El Awady". Al-Youm Al-Sabea. Archived from the original on 2020-03-05. Accessed on 2016-09-04.

- ^ "The return of 19 pieces of King Tut's artifacts is a great achievement". Al-Ahram. August 2, 2011. Archived from the original on 2018-08-07. Accessed on 2015-10-05.

- ^ "Salwa Abdel Rahman as director of the Egyptian Museum. Al-Watan. December 3, 2012. Archived from the original on 2018-08-08. Accessed on 2016-09-04.

- ^ "We publish the resume of the new Minister of Antiquities". The seventh day. June 16, 2014. Archived from the original on 2020-03-05. Accessed on 2016-09-06.

- ^ "Former Egyptian Museum director reveals Nasser's connection to 'burning' NDP building, welcomes decision to demolish it". Sada al-Balad. Archived from the original on 2016-09-24. Accessed on 2016-09-06.

- ^ Zahi Hawass (October 28, 2000). "The story of the pyramids of Egypt(21)". Al-Ahram. Archived from the original on 2018-01-24. Accessed on 2016-09-04.

- ^ a b Moushira Moussa, Jehan Mustafa (December 12, 2002). "Suzanne Mubarak inaugurates centennial celebration". Al-Ahram. Archived from the original on 2006-02-11. Accessed on 2016-09-06.

- ^ Moushira Moussa, Jehan Mustafa (December 12, 2002). "Suzanne Mubarak inaugurates centennial celebration". Al-Ahram. Archived from the original on 2006-02-11. Accessed on 2016-09-06.

- ^ "113 years since the opening of the Egyptian Museum. A visitor's gateway to the magical time of the pharaohs". Cairo Gate. November 14, 2015. Archived from the original on 2015-11-16. Accessed on 2016-09-04.

- ^ Abdel Azim Mahmoud Hanafi. "The Story of the Egyptian Museum". Cairo Magazine. Archived from the original on 2016-09-13. Accessed on 2016-09-04.

- ^ Taha Ali (August 4, 2011). "Gaston Maspero. The first director of the Egyptian Museum was paid a thousand pounds a year". Asharq Al-Awsat. Archived from the original on 2018-08-07. Accessed on 2016-09-06.

- ^ "Maspero's file unveiled at the archives 95 years after his departure". Al-Ahram. August 1, 2011. Archived from the original on 2018-08-08. Accessed on 2016-09-04.

- ^ a b Ahmed Mansour (June 19, 2015). "The Egyptian Museum in Tahrir : Kings, monuments and tales of ancient Egypt". The seventh day. Archived from the original on 2020-03-05. Accessed on 2016-09-04.

- ^ Wael Ibrahim El-Desouki. "Establishment of the National School of Egyptology". Al-Ahram. Archived from the original on 2017-01-05. Accessed on 2016-09-06.

- ^ "The Egyptian Museum in Cairo". www.memphistours.com. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ^ "Egypt's Pharaohs' Golden Parade: A majestic journey that history will forever record". Egypt Today. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- ^ "Dans la cour du musée du Caire, le monument de Mariette... et les bustes qui l'entourent". egyptophile.blogspot.nl. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

Sources

[edit]- Reeves, Nicholas (2015). "Tutankhamun's Mask Reconsidered". In Oppenheim, Adela; Goelet, Ogden (eds.). Bulletin of the Egyptological Seminar. Vol. 19. Egyptological Seminar of New York. ISBN 978-0-9816-1202-7.

Further reading

[edit]- Brier, Bob (1999). The Murder of Tutankhamen: A True Story. ISBN 0-425-16689-9.

- Montet, Pierre (1968). Lives of the Pharaohs. World Publishing Company.

- Wafaa El-Saddik. The Egyptian Museum. Museum International. (Vol. 57, No.1–2, 2005).

- Tiradritti, Francesco, ed. (1999). Egyptian Treasures from the Egyptian Museum in Cairo (Hardbook). Photography by Araldo De Luca. New York. ISBN 0-8109-3276-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)Also published, with variant titles, in Italy and the UK. Reviews US ed. - Wilkinson, Toby (2020). A World Beneath the Sands: Adventurers and Archaeologists in the Golden Age of Egyptology (Hardbook). London: Picador. ISBN 978-1-5098-5870-5.