Eglinton Country Park

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Eglinton Country Park is located on the grounds of the old Eglinton Castle estate in Kilwinning, North Ayrshire, Scotland (map reference NS 3227 4220). Eglinton Park is situated in the parish of Kilwinning, part of the former district of Cunninghame, and covers an area of 400 ha (990 acres) ([98 acres (40 ha)] of which are woodland. The central iconic feature of the country park is the ruined Eglinton Castle, once home to the Eglinton family and later the Montgomeries, Earls of Eglinton and chiefs of the Clan Montgomery. Eglinton Country Park is managed and maintained by North Ayrshire Council and its Ranger Service.

Spier's Parklands

[edit]

Spier's Old School Grounds on Barrmill Road, Beith is an amenity for the communities of the Garnock Valley (Dalry, Glengarnock, Kilbirnie, Longbar, Beith, Auchengree, Greenhills, Burnhouse, and Barrmill). Pedestrian access is 24x7.

The Spier's parklands are patrolled by the NAC Ranger Service. The Friends of Spiers (FoS) are a group based at the parklands, dedicated to the enhancement, maintenance, and utilisation of the old Spier's School Grounds. Spier's is owned by the Spier's Trust and leased by NAC. It has a network of wheelchair-friendly paths and informal routes which are surfaced with bark chips. A series of events are held at the grounds each year.

Stevenston Beach and Ardeer Quarry

[edit]

These wildlife sites have public access at all times and are regularly patrolled by the NAC Ranger Service who also carry out basic conservation tasks aided by volunteers and local groups. The Stevenston sand dunes are a designated local nature reserve and work here is linked to the priorities within the site's Conservation Management Plan.

Activities

[edit]Two children's playparks are provided. There are wet weather shelters. The Rackets Hall can be hired for birthday parties, conferences, exhibitions, and other events. A soft play facility is located for hire within the Rackets Hall.

Equestrian rides (bridle paths)

[edit]Within the park there is an extensive bridle path network extending to around 11 km. Of this route a shared paths makes up about 5 km of the route on which riders must give way to walkers and cyclists. The track meanders pleasantly beside fields and woodlands.[1]

Eglinton loch and the Lugton Water

[edit]

The Lugton Water meanders through the park, and several weirs were built at intervals along the river to raise the water level for ornamental reasons. Several mills were powered by the Lugton Water as shown by names such as 'North and South Millburn', situated near the hamlet of Benslie. The 12th Earl (1740–1819) altered the course of the Lugton Water.[2]

The 6.5 ha loch, 6 metres deep, was created in 1975 through the extraction of materials used in the construction of the A 78 (T) Irvine and Kilwinning bypass. It is marked on old maps as being an area liable to flooding and was the site of the jousting matches at the 1839 Eglinton Tournament. It is well stocked with coarse fish, and is a popular spot for anglers[3] and bird watchers.

The Irvine New Town Trail

[edit]The Irvine New Town Trail is a 19 km (12 mi) long cycle path used by many joggers, walkers, dog walkers and cyclists in the area. The route forms a ring as there are no start and end points. The trail passes through Irvine's low green, and goes up to Kilwinning's Woodwynd and Blackland's area. The route passes through the Eglinton Country Park, carries on to Girdle Toll, Bourtreehill, Broomlands, Dreghorn and carries on to the Irvine Riverside and back to the Mall and the Low Green again.[4]

The Belvedere Hill and other pedestrian areas

[edit]A plantation is situated on 'Belvedere Hill' (the term 'Belvedere or Belvidere' literally means 'beautiful view') (until 2011 it also had a large classical central 'folly' feature) and vistas radiating out from a central hub, technically termed 'rond-points' (plantations located on rising ground with several vistas radiating from a central point). This style of woodlands and vistas or rides is a restoration of the layout of the entire area surrounding the castle in the 1750s prior to the remodeling which was completed by 1802. General Roy's map of 1747 - 52 shows that the ornamental woodlands were a series of these radiating rond-points of different sizes, sometimes overlapping each other.[5] The 'old' Eglinton Park farm, circa 1950s, lies to one side of this feature. Many other footpaths are present, a number of which are not shared with cyclists or horses.

- Views within Eglinton Country Park

-

The suspension bridge over the Lugton Water

-

The Belvedere Hill plantation

Wildlife

[edit]Birds

[edit]Recent resident breeding species include: the robin, finch, tit, thrush, pheasant, grey partridge, tawny owl, kestrel, sparrowhawk, great spotted woodpecker, skylark, yellowhammer and tree-creeper.

Resident (but non-breeding) species include: the buzzard and winter visitors: the fieldfare, redwing, occasionally the waxwing and sightings of the hen harrier and kingfisher.

Wildfowl include: the goldeneye, wigeon, tufted and mallard duck with whooper swan and goose on passage. There are also woodcock, snipe, curlew and lapwing.

Summer migrant species include: the swift, swallow and martin; willow, sedge and grasshopper warbler, blackcap and chiffchaff. Exotic sightings include cuckoos, white stork, black swan and a amazingly a flamingo! This was reported by Charlie Watling of Kilwinning around 2005.[6]

Mammals

[edit]Hedgehogs, foxes, moles, otters, pipistrelle bats, mink and roe deer are found in the park and may be seen with luck or by being patient and silent.

Other wildlife

[edit]Surveys carried out by the Scottish Wildlife Trust and others have shown that the park also has a good variety of mushroom, bracket, jelly and other species of fungi. The park has a good gall diversity, such as knopper on acorns, tongue on alders, robin's pincushion or rose bedeguar gall on wild rose, cola nut on oak and witch's broom on birch.

The 'Old Wood' containing the ice house has a good plant diversity due to the fact that it is long established and relatively undisturbed, unlike the park's plantations which are of a comparatively recent origin. Chapelholms wood shows a similar high biodiversity. Plants such as dog's mercury, tussock grass, bluebells and honeysuckle are indicators of old deciduous woodlands. Snowdrops are a highlight of spring in the park. A few specimen trees from the estate days survive, especially sycamores (Acer pseudoplatanus) or plane trees as they are traditionally known in Scotland. The park is one of the relatively few sites in Scotland where the upright hedge bedstraw (Galium album) grows.

Species conservation

[edit]The park is acting as a part of the conservation effort to ensure the survival of three species of the rare indigenous and endemic trees commonly called the Arran whitebeams, native to that island and found nowhere else in the World. Chapelholms Wood has been designated as a Wildlife Site by the Scottish Wildlife Trust in recognition of the quality of its habitats and the species diversity it exhibits.

-

Sorbus arranensis in flower at the park

-

The giant puff-ball mushroom (Calvatia gigantea) near the castle

-

The jelly ear (Auricularia auricula-judae)

-

The oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus)

The History of Eglinton Country Park

[edit]The castle, gardens and estate

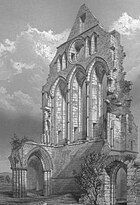

[edit]The castle

[edit]

The original castle of the Eglintons may have been near Kidsneuk, Bogside (NS 309 409) where a substantial earth mound or motte stands and excavated pottery[7] was found tentatively dating the site to the thirteenth century.[8][9]

The earliest known castle, which even then was the chief seat of the Montgomeries, was burned by the Cunninghames of Glencairn in 1528 and rebuilt afterwards. The mill was also destroyed as well as the muniment chests containing the Montgomerie charters, etc.[12] The older castle was completely demolished in 1796; having been first modified by the 9th Earl who commissioned William Adam (1689–1748) to build a kitchen block and associated back court.[13] An 1840 engraving shows three arches, and other differences to the later Tournament bridge built further downstream.[14] The usual spelling is 'Eglinton', however Eglintoun, Eglintoune or Eglintown are encountered in old books and maps. The Eglinton Castle ruins, despite their appearance, are of a relatively modern building, the mansion having been completed as recently as 1802. Eglinton was the most notable post-Adam Georgian castle in Ayrshire.[15]

One of the side wings of the 1802 castle was known to the servants as Bedlam, this being where the Montgomerie's children had their rooms.[16][full citation needed] The central saloon of the castle was 36 feet (11 m) in diameter and reached up the whole height of the castle, some 100 feet (30 m).[17] The Category B Listed 1802 castle was un-roofed in 1929, being in poor structural condition after the contents sale of 1925,[18] and fell into ruins.

Amongst many items of interest, the castle contained a chair built from the oak timbers of Alloway kirk and the back of the chair was inlaid with a brass plaque which bore the whole of Burn's poem 'Tam o' Shanter'.[19] This was sold, together with much of the family paintings, the Earl's suit of armour, etc. at the 1925 sale of contents.[18]

4 Commando and the Royal Engineers[20] used it for exercises during the second world war, destroying two of the towers, and it was also used for naval gunnery practice. In the 1950s further damage was done and the remains were finally demolished to the level they are today (2007) in 1973.[21][22] The house reputedly had 365 windows, one for each day of the year.[16][full citation needed]

Groome in 1903 had stated that "Everything about the castle contributes to an imposing display of splendid elegance and refined taste."[17] An escape tunnel is said to run from the old castle to the area of the rockery on the castle lawns. The appearance of the old waterfall may have inspired this story as it looks like a sealed doorway.[23]

The park and gardens

[edit]

The park was used as a training camp; for vehicle maintenance and as a preparation depot for the Normandys and North Africa landings during World War II. The remnants of this era are visible in the form of Nissen huts, still in use today and the foundations of other wartime buildings.[24] The army left the estate in a very dilapidated condition with abandoned vehicles left in a number of places. The partly buried remains of vehicles still exist in places.[25]

The architect had been John Paterson (1796–1802) and John Baxter designed the Redburn Gateway & lodges; the cast-iron Tournament bridge may have been originally designed by the famous architect David Hamilton. An older bridge with three arches, the one actually used for the 1839 Tournament, had stood further up the river towards the castle as described and shown in several contemporary prints, books and maps[26][27]

The landscape gardens, were designed by John Tweedie (1775–1862), and laid out for Alexander, the 10th Earl, together with extensive tree plantings. The earl was a noted agricultural reformer and pioneer. The landscaping works were finished by 1801 and replaced an older style, now represented by the replanted Belvedere Woods.[28] The gardens were laid out by John Tweedie (1775–1862), a native of Lanarkshire who also worked at Blairquhan Castle in 1816, Castlehill in Ayr; in 1825 he emigrated to Argentina where he became a leading agriculturist and plant-hunter.[29]

At their peak the policies (from the Latin word 'politus' meaning embellished[30]) and gardens of the estate covered 1346 acres (1500 Scots acres[31]), made up from 624 acres (253 ha) of grassy glades, 650 of plantations, 12 acres (4.9 ha) of gardens, etc. A high stone wall surrounded much of the park, which had one six-mile (10 km) long carriage drive and another drive of two miles (3 km) length inside this wall. Gates and / or lodges existed in many places, such as at Corsehill, Chapelholms, Redburn, Weirstone (Flushes), Kilwinning, Mid, Millburn, Girdle, Hill and Stanecastle. John Stoddart visited in 1800 on his tour of Scotland and wrote glowingly of the estate as a creation of art.[32] The total acreage of the Earl of Eglinton's holdings was 34,716 Scots Acres in 1788.[33] A Scots acre was 1.5 English acres.

The estate offices, coach house and stables block were probably built in the 18th century by John Paterson, however it is suggested that the architect was Robert Adam.[34] Old photographs show that a pair of matching entrances to the central 'archway' existed, but were replaced by windows and walling at an unknown date. The building was first converted and extended to form a factory, opened by the 17th Earl in 1958 for Newforge Canning Factories (Ireland), otherwise known as Wilson's canning factory. This factory has been out of use for some years and is currently undergoing redevelopment into residential properties consisting of 12 apartments within the listed stable building and 24 detached houses with the former factory compound. The 2 car parks adjacent to the factory are to be removed and replaced with one single car park situated towards the visitor center.

A bowling green, a little to the west of the Tournament Bridge in what is now the Clement Wilson gardens, was said to be the finest in Britain; a bowling house also existed.[35]

A tennis court was situated on the grass to the west of the castle. A deer park surrounded the castle and this is recorded as having contained many fine old trees and unusually, a 'Deer shelter'.[36] The whole deer herd from Auchans Castle near Dundonald was removed in the 1820s by the Earl of Eglinton to the Eglinton Castle policies. The woods around the property were extensive and old; Auchans had been famed as a preserve for game.[37] An area called 'Ladyha Park' used to contain a colliery; it lies towards the Kilwinning gate lodge (previously the Weirston gate); on the other side of Ladyha (Lady hall) park lies the old fish pond in a field called the 'Bull Park' and the 'Swine Park' is nearby.

Other features in the grounds of the estate were the 'Formal Gardens' lying between the walled garden and Lady Jane's cottage, commemorative marble pillar, Eglinton house (previously the 'Garden Cottage'), Weirstone house, the Fish Pond, the Redburn 'Dower' House (demolished circa 2006), Eglinton Mains farm (home of the estate foresters), etc.

The curtain walls of the Walled Kitchen Garden with two roofless Gazebos or temples survive. One was used as a resting parlour and the other was an aviary.[27] They were both topped with statues as shown in surviving photographs. A handsome gate of cast-iron stood at the end of the bridge and its pilasters had two of the four statues representing the four seasons, the other two being on the temples.[27][38] Loudon in 1824 comments the trees of the park are large, of picturesque form and much admired. The kitchen garden is one of the best in the country. The park trees were mainly beech, with oak and elm also present. An article in 1833 in the Gardeners' Magazine makes similar remarks and comments on the ... many hundred feet of hot houses; however, it also notes that the ... grounds are not kept up as they ought to be.[39] A hedge maze or labyrinth existed in the grounds up until the 1920s.[25]

The Lugton Water was diverted in the 1790s to run behind the Garden Cottage, rather than in front of it. Five ponds were created by weirs.[40] The gardens, amongst other things, possessed a peach house, an orangery, a vinery, a melon house and a mushroom house.

A large number of cottages, such as Fergushill, Higgins (on the old toll road), Millburn, Chapel Croft, Diamond, Gravel, Flush and Hill, and some miners rows existed at one time or other, together with place names such as Swine Park,[38] Chapelholm, Knadgerhill, Irvine March wood, Meadow plantations and Long Drive; an area close to Eglinton Mains called 'The Circle', Crow and Old Woods, The Hill, also known locally as Foxes Lodge,[41] etc., etc. Thomas and Anne Main once lived at The Hill cottage and their daughter Hetty was born there; they moved to Eglinton Mains farm.[35] The 'Circle' was the large circle in the middle of a 'star burst' belvedere feature of the 1747 estate plantings. The area between Corsehillhead and Five Roads was known as 'Brotherswell'.[42]

Captain Moreton's Eglinton Castle croquet

[edit]

The earliest known reference to croquet in Scotland is the booklet called The Game of Croquet, its Laws and Regulations which was published in the middle 1860s for the proprietor of Eglinton Castle. On the page facing the title page is a picture of Eglinton Castle with a game of "croquet" in full swing.[43]

A croquet lawn existed on the northern terrace, between the castle and the Lugton Water, also the old site of the marquee for the tournament banquet. The 13th Earl developed a variation on croquet named 'Captain Moreton's Eglinton Castle Croquet', which had small bells on the eight hoops 'to ring the changes', two pegs, a double hoop with a bell and two tunnels for the ball to pass through. In 1865 the 'Rules of the Eglinton Castle and Cassiobury Croquet' was published by Edmund Routledge. Several incomplete sets of this form of croquet are known to exist and one complete set is still used for demonstration games in the West of Scotland.[43] It is not known why the earl named it thus.[44]

- Views of the old walled gardens and temples

-

A part of the old walled 'Kitchen Garden'; a Gazebo, a matching partner still exists at the other end towards the Castle Bridge

-

An old entrance to the walled kitchen Gardens

-

The site of the old 'Formal Gardens' from the walled gardens

-

Surviving walls from the old 'Formal Gardens' beside the Lugton Water

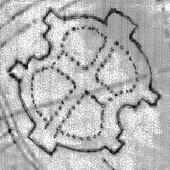

The Baroque landscape feature

[edit]

A highly unusual landscape feature of some considerable size was laid out as a bilaterally symmetrical design near Benslie hamlet and is shown on the 1750s Roy map. It lies outside the ornamental woodlands and has the 'appearance' of the foundations of a large building, although it was made up of trees.[5] 55°39′0.8″N 4°38′37.7″W / 55.650222°N 4.643806°W This odd shaped park or 'baroque park' feature has similarities to a 'Celtic' cross shape, a topographical feature mapped by Roy's surveyors. It may be a small deer hunting park or baroque garden layout possibly similar to one that existed at the Optagon Park, Alloa Estate, Clackmannanshire; which in turn was after the Dutch taste and modelled on Hampton Court, the favourite home of King William; a Dutchman.[45][46] On the 1938 OS map the Montgreenan side of Benslie wood retains the shape of that part of the baroque garden. It is possible that this area was incomplete when mapped by Roy in the 1750s.

Listed structures in the park

[edit]The ruined castle is listed C (S) and the Rackets Hall is listed B. The Tournament Bridge by David Hamilton, which has lost its original Gothic parapet, is listed B. The offices and stables built around 1800 are also listed B; the stables are being converted into housing, but the office frontages have been preserved. Other listed buildings within the park are the Kilwinning Gates, B; the Doocot at the mains Farm, B; the Garden Cottage 1798, B; the walled kitchen gardens and the two derelict gazebos or temples, C (S); the Eglinton Park Bridge, B. The Ice House, Belvedere Gates, and the Mid Gates are no longer listed.[39][47]

The Stables, coach house and offices

[edit]The 1828 map marks this building as 'offices', however it clearly served the function of coach house and stables for coach horses as well. It was also known as 'Adam's Block'.[11] More stables were built in the 1890s for the farm carthorses. Some of the dressed stone blocks from which the old stables and offices are constructed have masons marks cut into them. This suggests that they were taken from the ruins of Kilwinning Abbey in 1792 when one of the Earls had the stables built on the site of a 16th-century cottage. Ness[11] states that the stone came from a building called 'Easter Chaumers' which was part of the abbey. The design of the Montgomerie family crest above the entrance is identical to that on the castle ruins. The architect John Paterson built both, one being the 'trial piece' for the other.[48] Kerelaw Castle near Stevenston contained many carved stone coats of arms taken from the old abbey, which was clearly seen as being a convenient source of dressed or ornately carved stone for many a 'new' building in 'old' Cunninghame. The stables at Rozelle House in Ayr bear a more than passing resemblance to those at Eglinton.[49]

Architects drawings from March 1930 survive for plans to adapt the stable buildings as a residence for the Earl of Eglinton and Winton, but nothing seems to have come from this initiative.[50]

-

The ruins of one of the two listed 'temples'; one was a resting parlour and the other an aviary

-

The Montgomerie family crest and motto - 'Gardez bien' - 'Guard Well' or literally 'Watch Out'!

-

The old Eglinton offices and stables

-

Weirston House, home of the estate factor

- Views of Eglinton Castle and the old offices / stables / factory

-

A clear view of the tower and the remaining side wall

-

The Montgomerie family crest on the castle ruins. The Motto reads as 'Garde Bien' translating as 'Hazard Yet Forward' or 'Guard Well'.[51]

-

The Montgomerie family crest on the Stables/offices/coach house

-

Stables frontage restoration in 2009

The carthorse stables, gas and electricity works

[edit]The old working horse stables, etc. have been converted into offices, a tea room, toilets, etc. A small Doocot is present in the courtyard. The old OS maps show that by 1897 a gas works had been established here to supply the castle and offices. By 1911 this gas works had been replaced by an electricity power station in a new building which has been restored and is the present day park workshop.

The Rackets Hall

[edit]Rackets or Racquets in American English, is an indoor sport played in the United Kingdom, United States, and Canada. The sport is infrequently called "hard rackets", to distinguish it from squash (formerly called "squash rackets"). Eglinton has a 'Racket Hall' which is first shown on the 1860 OS map, but was built shortly after 1839, the first match being recorded in 1846. The floor is of large granite slabs, now hidden by the wooden floor. It is the very first covered racquet court, built before the court size was standardised and is now the oldest surviving court in the World, as well as being the oldest indoor sports building in Scotland. It has been restored and converted into an exhibition area.[16][full citation needed] In 1860 the earl employed a rackets professional, John Charles Mitchell (fourteen times champion) and Patrick Devitt replaced him. Mitchell owned a pub in Bristol with its own rackets court and this was named the "Eglinton Arms", having been the "Sea Horse" previously. As a player, Devitt once lost a £100 wager to a Mr Young.[52]

Lady Jane's cottage ornée

[edit]

Aiton states that "Near to the gardens, in a remote corner, more than half encircled by the river, a remarkably handsome cottage has been reared, and furnished, under the direction of Lady Jean Montgomery, who has contrived to unite neatness and simplicity, with great taste, in the construction of this enchanting hut. That amiable lady, spends occasionally, some part of her leisure hours, about this delightful cottage: viewing the beauties, and contemplating the operations of nature, in the foliage of leaves, blowing of flowers, and maturation of fruits; with other rational entertainments, which her enlightened mind is capable of enjoying." Such a romantic cottage was called a 'cottage ornée'.

Lady Jane Hamilton, the 13th Earl's Aunt built or extended 'Lady Jane's Cottage' which lay beside the Lugton Water. She used this thatched building to teach domestic economy to peasant girls. This may represent a later use of Lady Jane's cottage. Nothing now remains of this cottage, other than a 'crop' mark on aerial photographs, although the 1938 OS map still shows it.[53] A persistent local tradition is that Lady Jane had in fact been banished to this cottage for some misdemeanour and was led back to the castle by a manservant every evening.[54] It was a ruin by 1928.[35]

A similar style of cottage existed on the Fullarton estate in Troon as a lodge house near the Crosbie Kirk ruins.[55] Lilliput Lane has produced a model of Lady Jane's cottage.[56]

The gravestone to a faithful family pet dog, Toby, once stood near Lady Jane's cottage and the ornamental pillar memorial; but has since been lost. The inscription readThey take the good, Too good on Earth to stay; The bad was left, Too bad to take away.[57] This dog's gravestone may originally in the Old Wood as recorded by Robin Cummell; Toby had belonged to the 10th Earl.

In 2012 Rathmell Archaeology carried out an investigation at the site, confirming its location and locating the site of the old footbridge that led to it. Further excavations were carried out at the site in 2017.

The Old Wood Ice House

[edit]

Ice or snow houses were introduced to the United Kingdom in around 1660 and were commonly brick lined, domed structures, with most of their volume underground. An ice house lies in Old Wood, fairly near to the doocot on the Draught Burn, built by the 10th Earl for £25. 55°38′31.5″N 4°39′28.2″W / 55.642083°N 4.657833°W It was not very successful and was later modified to increase its efficiency. It had a total of three doors to reduce the entrance of heat. The restoration involved an almost total external rebuild and it is not known if the present structure accurately represents the original; it is known that slates covered the exterior of the original structure. During the winter ice and snow was taken from the fishpond, etc. or even imported via Ardrossan Harbour if the winter had been too mild.[16][full citation needed] A second ice house is recorded on the 1860 OS on the edge of the Ladyha Deer Park close to the Weirston to Eglinton Kennels estate road; the design and location suggest that this was involved in the preparation and storage of venison.

Game larders

[edit]These were partly underground structures with stone foundations, used to store pheasants, rabbits, and other game, apart from venison. Ice was taken from the ice houses to the larders, which were placed conveniently beside the footpath to the laundry, as close to the castle kitchens as possible.[58] Nothing remains today. An 1807 map clearly marks a game larder in this position.[38]

Deer Park or Ladyha ice-house

[edit]The Deer Park ice house lay close to the lane leading to Eglinton Kennels from the Tournament Bridge. It is marked as an Ice House on the 1911 OS map, its later date, style of construction and position close to the deer park suggests that it was a place linked to the preparation and storage of venison from the deer park. Ice for this may have come from the nearby fishpond; emptied into the building via the two hatches in the roof. At this 'late' date in the history of the estate it may have been a commercial activity.[58]

This ice house was at some point converted into a cattle shelter by the opening up of one end of the building, the insertion of two air vents in the remaining end wall and the blocking up of the original side entrance. The ice-house may also have been partly uncovered and the brick roof coated with concrete. The building was totally demolished, circa 1990, however it was photographed first. 55°39′0.5″N 4°40′16.1″W / 55.650139°N 4.671139°W

-

The old entrance and the demolished front wall.

-

The end facing the old castle; wall intact, but ventilation holes created.

-

The interior, showing one of the 'skylights'.

-

The interior view of the old entrance.

- Views of the Doocots and Old Wood Ice house

-

The Eglinton mains doocot prior to restoration. The local council had used it as a vehicle store.

-

The doocot at the Tournament cafe courtyard

-

The ice house in the Old Woods from near the Draught Burn.

-

The ice house entrance.

- Landscape features and miscellaneous views

-

The Lugton Water and one of the two gazebos, circa 1880.

-

The old estate offices and stables prior to the factory's construction.

-

The entrance to the walled kitchen garden.

-

Movable stone blocks in the old heated wall of the walled garden.

-

The hollow heated wall of the walled gardens.

-

Caravans on the site of the old cricket ground.

-

Eglinton House, formerly the 'Garden Cottage'.

-

Eglinton Kennels farm, previously Laigh Moncur.

-

The ornamental pillar memorial to Hugh Montgomerie at the Visitor Centre, previously at Lady Jane's cottage woodland.

-

Tombstone to a favourite Spaniel that once belonged to Lady Montgomerie.

-

Morven House and kennels (privately owned) near 'The Circle', across from the large doocot. Gravel Cottage is just out of sight.

-

Curling at the Eglinton Flushes (Weirston) in 1860. Arran can be seen in the background as well as the Eglinton steelworks.

- Views of Eglinton's burns, ponds and bridges

-

Draught burn bridge. This burn rises in the wetlands of Girgenti near Auchenharvie Castle.

-

The Lugton Water near Fergushill and the old Waggonway Bridge.

-

The Lugton Water near the ford. A source of ice.

-

The Castle or Laundry Bridge.

-

Belvidere Loch.

-

The chapel or Diamond bridge over the Lugton Water.

-

A weir on the Lugton Water near the suspension bridge.

-

The Lugton Water and one of the two Gazebos circa 1890.

-

The Stable's, Castle or Lady Jane's bridge over the Lugton Water.

-

The old fish pond in the Bull Park.

-

The Settling Pond near Cairnmount.

-

The Redburn near the Drucken or Drukken Steps.

The doocots

[edit]

A large ornamental Gothic lectern style Doocot (Scottish Colloquial) or dovecote is located near the scant remains of the Eglinton Mains farm, situated on the B 7080 'Long Drive' towards Sourlie Hill interchange. 55°38′18.2″N 4°39′26.8″W / 55.638389°N 4.657444°W It is said to have come from Kilwinning Abbey which was a possession of the Earls. However, the design is one from the 16th or 17th century,[59] the abbey having been dissolved in around 1560. The building suffered a fire and when rebuilt the crow steps and battlements may have been left out. Its style is in keeping with the 1802 castle, however the ornamental door carvings and the stones may have come from the old abbey although one is a concrete facsimile. The line of stone jutting out from the walls was a 'rat course' to keep these vermin out of the doocot. Ness[60] categorically states that the dovecot was moved to its present position in 1898 - 1900 and was hopeful that it would be restored to the abbey grounds.

It was used to breed house doves and pigeons which the 15th Earl was particularly partial to.[61] Doocots were not built to supply meat over the winter as the preferred bird was the young squab or squeakers, which were tender and fatty.[62] A smaller doocot is built into the stable buildings overlooking the open courtyard. The larger doocot may have been built as a pheasantry, as it is not marked on OS maps as a doocot and old photographs do not show any internal nesting boxes. It does not appear until 1911 on OS maps and is located at the edge of a pheasantry enclosure. A second pheasantry was based at Gravel House according to the OS maps; a kennels was also being located there. Pheasantries were used for raising pheasants for field-sports on the old estate.

Curling ponds

[edit]Old OS Maps show that the estate had several curling ponds, one set of three at the Flushes near to Weirston House beside the A 737 Kilwinning Road and the other in between the Stanecastle and Girdle gates on the old Lochlibo Road. The Stanecastle pond had a tarred bottom, giving better quality ice that could also be used for stocking the ice house. The three separate ponds, are recorded by Historic Scotland and the OS map near Weirston House. A contemporary watercolour (See gallery) shows a game being played at this site, called the Flushes. The Flushes Ponds were fed by the Bannoch Burn and a curling house was present, in which the traditional fare of pies and porter were provided for players, often followed by a night of entertainment at the castle.[63] Other curling ponds seem to have existed at the Kilwinning Road and on the opposite bank of the Draught Burn near the ice house in the Old Wood.

Cricket ground and pavilion

[edit]From 1911 the OS maps show a cricket ground and a substantial pavilion built by the 16th Earl, the latter being parallel to the Lugton Water. Two English cricket professionals were employed[64] to provide tuition and they lived in the 'Mid Gates' lodge (just off the main A 78 (T) entrance), which still survives. Neither the cricket ground nor the pavilion still exist, but part of the cricket ground area forms the site for caravaners, etc.

Redburn House

[edit]This property was a dower house of the estate, used to be situated opposite the Redburn gates. It had fine gardens with a summer house and a sundial; most likely the characteristic Scottish sundial type, although its present whereabouts are unknown.[58] Redburn was also the base of the Estate Factor at one time.[65] Archibald, the 17th Earl was born here.[35] It was used as a hotel for a number of years before being demolished and the site developed as a housing estate.

Kidsneuk Cottage

[edit]Lady Susanna Montgomerie, wife of the 9th Earl of Eglinton, was a renowned society beauty and her husband built for her at Kidsneuk a copy of the cottage orné, the Hameau de la Reine that Marie Antoinette had famously possessed at Versailles. This building, now a golf clubhouse, was thatched until the 1920s and is built of whin with steeply pitched roof sections and many gables.[66]

The Cadgers' Racecourse

[edit]During each August, Irvine's Marymass Festival takes place as it has done for several centuries. Part of the celebrations are horse racing held on the Cadgers racecourse (a cadger was a person who transported goods on horseback in the days before carts were introduced[10]) on the 'Towns Moor' which was part of the Eglinton estate. The course is clearly shown on a number of old maps, such as the 1775 map by Captain Armstrong, where it is called the 'Race Ground'.[67] Later the Montgomeries purchased the Bogside area and built a new racecourse for thoroughbred horses, at which the Scottish Grand National used to be held. The race moved to Ayr Racecourse in 1966 after the closure of Bogside Racecourse, where the race had been run over a distance of 3 miles 7 furlongs (6,236 m) since 1867. The 13th Earl brought steeplechasing to Scotland. His racing colours were his own tartan with yellow and his most successful horse, Flying Dutchman, won the Derby and the Saint Leger Stakes.[68] The 13th Earl was not much interested in hunting, however he did take part in 'point to points' at Eglinton.[69]

- Eglinton's gates and gatehouses

-

Stanecastle Gate circa 1840.

-

The Stanecastle gate in 2007.

-

Redburn gate circa 1910.

-

The old Girdle gate at Girdle Toll. The old gatehouse has been demolished.

-

The gates on the Kilwinning Road.

-

The Kilwinning gatehouse, formerly home to one of the estate gamekeepers.[70]

-

The Mid gate lodge

-

Millburn Lodge and gate on the line of the old Toll Road. A post 1858 building, home to one of the estate gamekeepers.[70]

-

The restored Belvedere or 'Egg Cup' gates near the visitor centre

-

Chapelholm Gate.

-

The ruins of Corsehill Lodge. Maggie's Well located nearby was the source of drinking water for this lodge.

-

The old well at the Draughtburn Gate near the doocot. A gardener, William Mullin once lived here. (Demolished during laying of water pipeline in 2016).

The Feudal lords of Eglinton

[edit]The Eglintouns

[edit]

Eglin, Lord of Eglintoun[71][72] is the first of the family recorded, living during the reign of King Malcolm Canmore who is better known for his father being King Duncan, murdered by Macbeth of Shakespeare fame. He may have been one of the Saxon barons who accompanied Malcolm (who died in 1093) on his successful return to Scotland. The name is also recorded as Eglun of Eglunstone in 1205; a Saxon name.[73]

The family continued to live at Eglinton until Elizabeth de Eglintoun, the sole heir, married Sir John de Montgomerie of Polnoon Castle at Eaglesham. Elizabeth's mother was Giles, daughter of Walter fitz Alan, Lord High Steward of Scotland, and sister of King Robert II.[74] When Hugh Eglintoun of that Ilk, her father, died soon after 1378 the Montgomerie family inherited the lands and hereafter Eglinton's history is bound up with that family.[75]

The Earls of Eglinton and the Clan Montgomery

[edit]

The Montgomerie family were involved in many historical events, however they are best known for the feud between themselves and the Cunninghames, Earls of Glencairn, living in and around Stewarton and Kilmaurs. In 1488 the Clan Montgomery burned down the Clan Cunningham's Kerelaw Castle. These two clans had a long feud, partly based on the rights of feudal superiority in old Cunninghame. In 1507 the 3rd Lord Eglinton was made the 1st Earl of Eglinton. During the 16th century the long-running feud continued between the Clan Montgomery and the Clan Cunningham. Eglinton Castle was burned down by the Cunninghams, and then the Montgomery chief, the 4th Earl of Eglinton, was ambushed and murdered by the Cunninghams at the Annick Water ford in Stewarton. The government of King James VI of Scotland eventually managed to get the rival chiefs to shake hands and keep the peace.[77][78]

The family crest on the castle ruins and the old stables is said to represent a wife, Edgetta (Egidia?)[79] or daughter of one of the Earls holding a severed head, plus an anchor. She was reputedly kidnapped in the 1600s and taken to Horse Isle off Ardrossan. Whilst on the island she developed the trust of her captor and promptly beheaded him. She was able to persuade her remaining captors to release her forthwith.[73] Another version has a Danish Prince as an ardent admirer who abducted her, only for her to kill him and then persuade the crew of his ship to return her. A link may also exist with the popular biblical story of Holofermes, an Assyrian general of Nebuchadnezzar. The general laid siege to Bethulia, and the city almost surrendered. It was however saved by Judith, a beautiful Hebrew widow who entered Holofernes's camp, seduced, and then beheaded Holofernes while he was drunk. She returned to Bethulia with Holofernes head, and the Hebrews subsequently defeated the Assyrian army. Judith is considered as a symbol of liberty, virtue, and victory of the weak over the strong in a just cause. The anchor is seen as a symbol of good luck. Together these are good reasons for why the family adopted her as their crest.

Lady Jean Craufurd, daughter of the Earl of Craufurd, became Countess of Eglinton having narrowly survived death as a child, when her home, Kilbirnie House, burned down on 1 May 1757.[80] On 29 July 1565 Queen Mary married Lord Darnley at Holyrood in Edinburgh. At the banquet held in the palace after the marriage the 2nd Earl of Eglinton waited upon Lord Darnley, together with the Earls of Cassillis and Glencairn.[81]

The present earl is Archibald George Montgomerie, 18th Earl of Eglinton, and 6th Earl of Winton (b. 1939). The heir-Apparent is his son, Hugh Archibald William Montgomerie, Lord Montgomerie (b. 1966). Skelmorlie Castle, near Largs, was the seat of the earl, who is still chief of Clan Montgomery. In 1995 the family moved to Perthshire.

The Eglinton tournament

[edit]

Eglinton is best known for a lavish, if ill-fated medieval tournament, organised by the 13th Earl. It opened on Friday, 30 August 1839 and it is said that the grand folly of the Eglinton Tournament, sprang directly from the disappointment of the so-called "penny coronation". The Government had decided to scale down the pomp of Victoria's Coronation; one role abolished was that of the Queen's Champion and his ritual challenge in full armour. This role would have fallen to the Knight Marshal of the Royal Household, Sir Charles Lamb of Beaufort, the stepfather of the 13th Earl of Eglinton.[82][83] The expense and extent of the preparations became news across Scotland, and the railway line was even opened in advance of its official opening to ferry guests to Eglinton. Although high summer, torrential rain washed the proceedings out. The tenantry of the Earl were provided with accommodation to view the proceedings.[84] The participants, in full medieval dress or armour, gamely attempting to participate in events such as jousting, held at what is now the Eglinton Loch.[85] Amongst the participants was the future Napoleon III of France.[86]

Friends and admirers of the 13th Earl presented him with a magnificent silver commemorative 'trophy' designed by Edmund Cotterill, made in a medieval Gothic style by Messrs. Garrard of London at a cost of £1,775. This trophy is now kept in Cunninghame House, headquarters of North Ayrshire Council, having been given to the people of Ayrshire by the 14th Earl.[87] A second silver trophy was presented by 300 citizens of Glasgow.[88]

The damask from the pavilion of Lady Seymour, the Queen of Beauty, was used to make the curtains of the great drawing-room in the castle.[88]

Amongst others, Benjamin Disraeli, Earl of Beaconsfield, described the tournament, 'weaving' it into his romantic novel Endymion.[89]

Within 100 years, Eglinton Castle and pleasure gardens were abandoned. The tournament, costing around £40,000, was a severe drain on the family fortune which, together with huge expenditure on the Ardrossan Harbour, the Glasgow, Paisley and Ardrossan Canal, and the Glasgow Bank failure, undermined the resources of a family who had been among the greatest landowning families of Ayrshire.[21][full citation needed]

The decline and the rebirth of Eglinton

[edit]

The Eaglesham lands, including the Polnoon estate,[92] were sold in 1842 after 700 years of ownership by the Montgomeries. The failure of the Glasgow Bank in 1878 lead to financial difficulties, which together with the poor state of the castle, resulted in the sale of the entire contents of the house between 1 and 5 December 1925. Subsequently, the house was un-roofed and the windows removed so that tax and rates were no longer payable; they amounted to £1000 per annum.[93][94] The Montgomerie family had moved to Skelmorlie Castle by December 1925.

By 1938 the OS map shows a municipal cemetery at Knadgerhill (opened in 1926) and Ayrshire Central Hospital near the Redburn gate in the Meadow Plantation. The War Department purchased parts of the estate for training purposes in 1939.[95] In 1948 the Trustees of the late 16th Earl sold most of the remaining parts of the estate to Robert Howie and Sons of Dunlop for £24,000.[96][97] The 17th Earl officiated at the opening of a food processing establishment in the old stables / offices. A large army vehicle storage facility was built in the estates Crow Wood area (this became Volvo Trucks) and the A 78 (T) with its interchanges and access roads cut through the southern section of the estate (mainly parts of the deer park and the Irvine March wood). Several housing schemes were to follow at Girdle Tool, Stanecastle, Knadgerhill, Sourlie, The Hill, etc.

The rebirth

[edit]The establishment of Eglinton Country Park by the old Irvine Development Corporation (IDC) and North Ayrshire Council saved much of the estate for the benefit of all the people of Ayrshire and beyond. Eglinton was designated as the 34th of 36 Country Parks in Scotland in 1986, officially opened by Professor Sir Robert Grieve and Kerry Anne Paterson. Mr. George Clark was the first Country Park Manager at Eglinton, succeeded by Mr. Cameron Sharp.[98][99]

The Wilson family had purchased the old offices, castle ruins, and other land from Robert Howie and Sons in 1950. Clement Wilson, the food processing factory owner, established the Clement Wilson Foundation (now known as the Barcapel Foundation Ltd.) which opened part of the grounds to the public, spending around £400,000 (around £4,317,000 in 2008 terms) on consolidating the castle ruins, planting trees, landscaping, making paths, creating a rockery and waterfall feature, restoring the Tournament Bridge, etc., etc. The waterfall no longer operates, but the waterfall feature and the large cistern that supplied the 'head of water' still exists at the bottom of the Belvedere in line with the old waterfall.

The Wilson family gave the park to Cunninghame District Council in 1978,[100] making it possible to establish Eglinton Country Park, a resource which now attracts over 250,000 visitors a year.

The factory, which employed 300 people, closed in 1997, following the acquisition of its business;a claim is that the factory was closed in order for the new owners to obtain its order book.

- Views of the old Eglinton stables and Auchenwinsey Farm

-

The old stables prior to conversion into the Tournament cafe

-

The stables prior to redevelopment into the visitor centre

-

The courtyard undergoing initial restoration

-

The Diamond Bridge undergoing restoration

-

An old ornate light on the stables

-

Auchenwinsey old farm in 2008

-

The Sourlie Open Cast coal mine

Palaeontology

[edit]During the open-cast mining operations at Sourlie several sub-fossil antlers of reindeer and also bones of the woolly rhinoceros were found. Both of these species was hunted by early humans, who may have caused their extinction.[101]

Archaeology

[edit]Scheduled and other structures

[edit]The Kilwinning Bridge and waggonway (B785 and Lugton River) and cropmarks of 3 circular enclosures (170m NNE of Eglinton Farm). Other noted features are the castle; cropmarks (NS317428); two cropmarks of circular enclosures (NS323426); and indeterminate cropmarks (NS314422).[35]

Prehistoric sites and finds

[edit]A small cordoned cinerary urn or beaker was found with several other urns in a tumulus very near to Eglinton Castle; it is now in the National Museum of Antiquities of Scotland. A search for the tumulus in the 1960s found that no traces remained.[102][103] A greenstone axe-hammer was found at Eglinton between the stables and the offices by a Mr. John Palmer in the 19th century. It is about 8 inches long and perforated near the blunt end. At Pytebog near Eglinton Kennels a stone axe was found in the 1890s.[104] Near 'The Circle' close to old Eglinton Mains farm are the remains of a short cist and aerial surveys show that the Belvidere Hill had a circular enclosure and ditch around its summit. Mesolithic flints and scrapers were found near North Millburn and in Chapelholm woods.[105] A ritual site has been identified at 'The Circle' near the Drukken Steps.

Lawthorn mount

[edit]A large and well-preserved prehistoric cairn or barrow is present at Lawthorn. Its name is suggestive of a court hill or justice hill, which is indeed the oral tradition. It is 21 paces in diameter at the base, 14 feet (4.3 m) in diameter at the top and 9 feet 8 inches (2.95 m) high; largely composed of boulders and one large boulder of graywacke stone, 7 feet (2.1 m) long, is partially buried on the top edge facing south. An unofficial dig in the 20th century revealed no finds.[107] See the 'gallery' for a photograph.[108]

Pre-reformation chapels

[edit]

Three chapels may have existed before the reformation, one in the vicinity of Chapelholm, Benslie wood and South Fergushill farm; one at Weirston and the other at Stanecastle gate. A Chapelcroft farm existed near Laigh Moncur, becoming the deer shelter in the Deer Park, now demolished and a Chapel Bridge over the Lugton Water.[109] A John Rankin in 1694 lived at the Eglinton Chapel.[35] The Weirston chapel is said to have been the private chapel of the Montgomerie family, dedicated to Saint Wyssyn.[110] A 16th-century house called Saint Wissing existed on the Irvine High Street near the Bridegate Corner and the lands of Saint Rynzen are recorded near Townhead.[111][112] The placename 'Ladyha' survives nearby, suggesting the Lady's (saint's) farm. Strachan states that a church of Saint Winin existed at Corsehill in the 7th century. Winin, Winning, Wissing or Wyssyn may be corruptions of the name Uinniau, better known as Saint Ninian.[113]

The foundations of the Stanecastle chapel were found a by Mr W Gray when digging drains. Judging from the foundations, the building must have been of considerable extent. Local tradition (J Fisher, Sevenacres) supports the findings, makes it more than probable that such a building once existed here. A chapel near Bourtreehill is mentioned by some sources. The 1858 OS map marks the site of a nearby cemetery and an intriguing subterranean passage or vault four feet below the surface; nothing is visible at the site today. A small village once existed here and one source has it that Stanecastle was once part of a nunnery[105] before it became the home of the Francis family; eventually passing to the Montgomeries.

Industrial archaeology

[edit]An unusually complex network of mineral railway lines, mainly running through the outer parts of the park, existed in the 19th and 20th centuries; the trackbed now being used as cycle paths in several places. A rare waggon-way bridge for the original 1.37 metres (4 ft 6 in) horse-drawn railway (later relaid as standard gauge)[114] still survives near South Fergushill farm on the B 785 Fergushill Road (see photograph), this being part of a 22-mile (35 km) long line running from Doura to Ardrossan.[115] A very complex set of collieries, coal pits and fire-clay works are evident from records such as old maps. Very little remains (above ground at least!) of the buildings and railway lines, but odd depressions in the ground, old embankments, coal bings and abandoned bridges all bear witness to what was at one time a very active coalfield with associated businesses and infrastructure. Ladyha (previously Lady ha') Colliery's ruins survived until 2011 when they were deemed dangerous and were demolished.

In the Chapelholms wood the 1938 map marks a hydraulic ram and cistern in a bend of the Lugton Water close to one of the old Fergushill collieries. Hydraulic rams harnesses the flow or current force of water to pump a portion of the water being used to power the pump to a point higher than where the water originally started. Rams were often used in remote locations, since it requires no outside source of power other than the kinetic energy of falling water.

The existing workshops at the Visitor Centre were, as stated, the site of the electricity 'power station.' This supplied the castle and a number of the estate houses with a 110 volt electricity supply. A Mr. Dickie was the last manager of the power station.[16][full citation needed]

Diamond was the name of a coalpit in the vicinity of Chapelholms which may explain the modern name 'Diamond Bridge' which is given to Chapelholms bridge and the name 'Diamond Lodge' which may have been the now demolished Chapel cottage.[116] Black Diamond was a favourite horse of one of the Earls, but any connection is pure speculation.

Dykeshead farm, near the existing Tournament Interchange, was the site of an estate smithy.

- Old railways around Eglinton

-

The 19th-century waggonway bridge (foreground) over the Lugton Water near Fergushill farm. The two bridges were known as the 'Elbo and chael.'[117]

-

A section of old railway trackbed at Corsehill looking towards the Bannoch Road

-

A loading dock onto an old siding at Benslie, on the closed and lifted Doura branchline

Lady Ha' colliery

[edit]

Key to plan; 1 - Downcast shaft & winding engine house; 2 - upcast shaft and winding engine/cum pump house; 3 - engineer's and blacksmith's shops; 4 - winch house; 5 - store; 6 - office; 7 - boiler house and chimney; 8 - screening house; 9 - fan/compressor house; 10 - wagon traverser; 11 - underground band haulage.

Ladyha no 2 pit was sunk in 1885 to a depth of 568 feet (173 m) and closed in May 1934, having struggled since its main customer, the Eglinton Iron Company, closed in 1928. The Eglinton Iron Company had opened in 1845 and at one point covered 28 hectares (69 acres) with eight furnaces and a 100,000 ton iron production per year. A fairly substantial brick-lined tunnel still survives which once carried a standard gauge railway line unobtrusively to Ladyha colliery, out of the Earl's sight and the smoke kept away from the kitchen gardens' greenhouses and plants.[118] Other such 'cosmetic' tunnels exist at Alloway and near Culzean Castle.[119] The tunnel was used during World War II as a bomb shelter and remains in good condition. The various colliery buildings were demolished in 2011, some years after an attempt had been made by the Country Park authorities to develop an industrial archaeology trail through the site.

Scottish Wildlife Trust reserves

[edit]Three areas within the old boundaries of the old Eglinton estate have become nature reserves, first developed by Irvine Development Corporation (IDC), but now owned and managed by the Scottish Wildlife Trust with free and open access to the public. These reserves are within easy reach of the park. Sourlie woods is situated on the Sustrans cycle route and the A736 Glasgow Lochlibo Road runs next to it. Sourlie shows unmistakable signs of the areas intensive and complex industrial past in the shape of remains of old railway embankments from the London, Midland and Scottish Railway's Perceton branch to Perceton colliery, spoil heaps and other signs of coal and other workings.

| Etymology |

| The meaning of Corsehillmuir is 'Cross' with hill and 'Muir' meaning moorland. All the more ironic when it is recalled that witches and other criminals were burned at the stake here.[120][121] |

Lawthorn woods (locally pronounced 'L'thorn' ) is a remnant of the Lawthorn plantation, which together with the 'Longwalk' and 'Stanecastle' plantations formed a much larger wooded area that once ran in an unbroken swathe down as far as Stanecastle and the old Stanecastle gate lodges. Lawthorn wood has easy access with a raised boardwalk running through it as a circular path. The other 'half' of the wood has long been reverted to pasture as old maps clearly show.[122]

Corsehillmuir plantation is another woodland reserve in an area which was mainly open pasture and moorland prior to the 19th century. It is situated off the B 785 between Mid Moncur and Bannoch farms. The historian John Smith records that this was the site of the ecclesiastical burning of witches and other criminals from the barony. The supposed witch Bessie Graham is said to have been burned at the stake at Corsehill Moor in 1649.[123][124][125] It might have been the site of the old churchyard of Segdoune, the name of Kilwinning prior to the establishment of the abbey.[126] The summits of the three low hills within the reserve are each surrounded by a circular ditch and dike, called 'Roundels' or 'hursts' (an embanked wood, formerly coppiced);[127] the actual purpose of the ditch and dike is unknown, but the exclusion of cattle is the most likely explanation. Ness[117] and others record that the 'Seggan' grew at Corsehillmuir, known also as the 'Messenger of the Gods', better known to us as the Yellow flag Iris.

- Sourlie, Lawthorn and Corsehillmuir nature reserves

-

The woodland nature reserve at Lawthorn

-

The boardwalk in the nature reserve at Lawthorn

-

Cairnmount Hill, a modern folly near the Sourlie nature reserve

-

Lawthorn mount; a Justice Hill and originally a barrow or cairn

Benslie and Fergushill

[edit]

The hamlet of Benslie, previously Benislay (1205), Benslee or Benslee square (1860), is situated next to the wood which once formed the 'Baroque garden.' Part of the garden outline survives on the Benslie Fauld farm side. The name 'fauld' may hold a clue at this is Scots for an area manured by sheep, cattle or possibly deer.[128] Fergushill church in Benslie was built to serve Montgreenan, Doura and Benslie. It was consecrated on Sunday, 3 November 1879 and the first minister was then Rev. William McAlpine.[129] It got its name from the Fergushill Mission which was based at Fergushill school. The old school house is still in existence at the junction of the road to Seven Acres Mill.[130] The manse is now a private house called Janburrow and stands at the entrance to the old Montgreenan railway station drive. Opposite is Burnbrae cottage, built as the Montgreenan Estate factor's house in 1846.

Fergushill church in Benslie was built to serve Fergushill, Doura and Benslie. It was consecrated on Sunday, 3 November 1879 and the first minister was then Rev. William McAlpine.[131]

Fergushill Cottage faced the Lugton Water just below the point at which the Fergushill Burn joins the river. Nothing much remains, however a Mrs. Miller once lived here and she recollected collecting water from the well which still exists as a circular low brick wall near to the site.

Fergushill Tile Works existed in 1858, but is not shown on the 1897 OS map. A number of freight lines have run through the village, connecting the main line near Montgreenan with the Doura branch.

The area is named after the family of that name. Fergushill of that Ilk, the local laird, Robert de Fergushill de Eodem had an extensive estate here in 1417.[132]

-

The Fergushill Burn where it joins the Lugton Water

-

The old well in the woods near Fergushill cottage

-

The ruins of Fergushill Cottage

-

The ruins of Fergushill Cottage and gardens remnants

The Robert Burns connection

[edit]

Robbie Burns wrote to Richard Brown, saying Do you remember a Sunday we spent together in Eglinton Woods and going on to say how he might never have continued with his efforts without this support.[133] The Drukken or Drucken Steps near Stanecastle was a favourite haunt of Burns whilst he was living in Irvine. A commemorative cairn at MacKinnon Terrace next to the expressway stands some distance from the original site of the steps, the site of which does still exist.[134] Another view is that the Drucken Steps were stepping stones on the course of the old Toll Road which ran from the west end of Irvine through the Eglinton policies to Kilwinning via Milnburn or Millburn;[135] crossing the Redburn near Knadgerhill (previously Knadgarhill[136]) and running past 'The Higgins' cottage, now demolished. The Higgins section is the only unaltered part where you can literally walk in the footsteps of Burns. The plaque on the commemorative cairn records that it was along this old toll road that Robert Burns and Richard Brown made their way to the woods of Eglinton.

The Scottish Campsite at Knadgerhill

[edit]

In 1297 Edward I sent a punitive expedition under Sir Henry Percy to Irvine to quash an armed uprising against his dethronement of John Balliol. The Earl of Carrick, Robert Bruce and others led the Scottish army, however after much argument they decided to submit without a fight. The submission resulted in the signing of the 'Treaty of Irvine', supposedly at Seagate Castle in Irvine. The story became embellished with a purely fanciful involvement of William Wallace in a brave action here. The memorial commemorates an event that might be best forgotten.[137]

The Eglinton geocaches

[edit]As an encouragement to people to explore the park a number of geocaches have been put in place.

The Eglinton Wildlife Site

[edit]The Scottish Wildlife Trust have designated part of the park as a 'Wildlife Site' through an agreement with the local council. The site is of 47 ha, with 6 ha of that being woodland. The map reference is NS 327 427, and the area covers Chapelholms Woods and the wetland associated with Eglinton Loch.

The 1774 Irvine - Kilwinning Toll Road

[edit]-

Ruins at the Draughtburn Gate

-

The course of the toll road from Draughtburn Bridge

-

The old toll road brig at the Millburn

-

The approach to the old Millburn brig. The stone in the foreground on the left has a Benchmark carved onto it.

The Drucken or Drukken Steps were stepping stones on the course of the old Toll Road which ran from the west end of Irvine through the Eglinton policies to Kilwinning via Milnburn or Millburn;[91] crossing the Redburn near Knadgerhill and running past 'The Higgins' cottage, which was occupied at one time by John Brown, gardener, and his wife Mary Ann. The Draughtburn Gate near Eglinton Mains was built to control or even prevent the movement of people along this old toll road. The course of the road can be followed until it is cut by the 'Long Drive' expressway.

Micro history

[edit]

Archibald, the 11th Earl, was Deputy Vice-Admiral of the Port of Troon, within the limits from Kelly Bridge to Troon Point.[138]

Like many other lairds the Montgomeries maintained a town house at Irvine, Seagate Castle.

A mountain and river in New Zealand were named 'Eglinton' after the 13th Earl of Eglinton.[139]

The Glasgow, Paisley and Ardrossan Canal was never completed and the section from Paisley to Glasgow was converted into a railway. The Glasgow terminus had been known as Port Eglinton and the Caledonian Railway station that replaced it was known as Eglinton Street Station.[140]

Eglinton has been used as a Christian name, as in William Eglington Montgomerie of Annick Lodge, who died 13 October 1884 age 84 yrs and is buried in Dreghorn cemetery.

A loch was planned in 1807, to be located where the existing loch is situated, but continuous with the river.[38] An 'Eagle Well' existed in the Sourlie Burn plantation.[141]

Dr. Duguid[142] visited Bonshaw, circa the 1840s and lists some of the items in the owners collection, including the stirrups from the horse that the 10th Earl of Eglinton was riding when he was shot and killed by gauger Mungo Campbell in 1769.

Rumours exist of a ley tunnel which is said to run from Kilwinning Abbey, under the 'Bean Yaird', below the 'Easter Chaumers' and the 'Leddy firs', and then underneath the Garnock and on to Eglinton Castle. No evidence exists for it, although the story may be related to the burial vault of the Montgomeries which does exist under the old abbey[143] Another ley tunnel is said to run to Stanecastle.

Three ghosts are associated with the castle; a white lady; a grey lady and a ghost seen within the surviving castle tower in 1997.[144]

A Charter of the time of Mary, Queen of Scots, refers to Eglinton's 'cunningaries' or rabbit-warrens.[145]

The 'gem ring' on the Ardrossan Academy badge is taken from the Eglinton coat of arms; the Earl of Eglinton having been one of the founders of the school.[146]

Another Eglinton Park is a public park located in the North Toronto neighbourhood of Toronto, Ontario, Canada, just west of the Eglinton Subway Station.

Knadgerhill was only acquired by the Earls of Eglinton in 1851 when they excambied part of the lands of Bogside Flats for them. This allowed the construction of the new entrance to the policies at Stanecastle via Long Drive.[147]

Eglinton castle is said by one of the gardeners to have had a room which was never opened. In about 1925 a young man from Kilwinning decided to take some of the panelling from a room in the castle as it was all being allowed to rot in the rain anyway, the roof had been removed. He went the castle to take away as much as he could carry, however one of the last pieces he selected left exposed the skeletal hand of a woman. The whole skeleton was later removed by a student doctor, but for fear of prosecution the matter was never reported to the police.[148]

The commercial park near Irvine, situated in what was called the 'Crow Wood', has been named 'Tournament Park' and a 'castle' folly has been constructed on the nearby roundabout, commemorating the event. One of the main entrances to the castle, the Redburn gates, ran through this commercial park, however nothing now is left of the old ornamental gates and lodges that existed here, with just a portion of sandstone walling existing at the side of a layby. It is not known what happened to this sundial, but it may survive at another site.

A pet's grave, that of the dog Toby, the 10th Earl's pet,[149] was located near Lady Jane's cottage, as was a marble memorial pillar to the 13th Earl's elder brother who died when he was six; the pillar being placed here because this was the site of the boys garden.[148] This pillar is now located in the woods next to the Visitor centre. Parts of the sculpture that sat on top of this pillar were found at the 'new' site in 2007 by the North Ayrshire Rangers Service. The base of the pillar carries this inscription:

|

"To the memory of his beloved grandson, Hugh |

The earl's dog was buried originally in the Old Wood by James Allen (a wright) with a young Robin Cummell at the scene and the earl giving him a sixpence with a gentle telling off for trespassing.[149]

The Barony Courthouse, owned by the Montgomeries, was situated opposite the old Abbey Green close to the Abbey grounds. It was demolished in 1970.[151]

After the castle had been un-roofed circa 1925 the estate largely continued for some time to be in the hands of the Montgomeries. Eglinton Mains farm was eventually abandoned and all the stock and equipment moved by a special train from Montgreenan railway station to Tonbridge Wells in Kent.[16][full citation needed]

The Redburn burn runs through the Eglinton estate from near Stanecastle and is named after the very high red iron salt content. It runs through the nearby 'Garnock Floods' Scottish Wildlife Trust nature reserve before flowing into the Garnock.

The Earls of Eglinton were keen hunters and the Eglinton Kennels (previously called Laigh Moncur) are situated off the B 785 Kilwinning to Benslie road.

Beside the Irvine New Town trail at the Old Wood is a large piece of machinery that appears to be of a military nature. This is actually a 'grubber' or 'rooter' which Robert Howie & Sons brought in to remove many of the old estate trees and create new pasture land. It was restored recently as part of a Countryside Ranger led project.

A boat house was present in 1828 beside the River Garnock, just below the old Redburn House on a loop of the river that was cut off and filled in as shown on the 25 inch OS map. The same map shows an area called 'Game Keppers' near Corsehill, the abode of estate Game keepers.[152]

The small gates from Stanecastle were purchased and restored by Lord Robert Crichton-Stuart circa 1970, husband of Lady Janet Montgomerie, daughter of Archibald Montgomerie, 16th Earl of Eglinton and Winton. Upon Lord Robert's death in 1976 they passed to a Mr. Simon Younger, in Haddington. The large gates were beyond 'economic' restoration.[153]

John Thomson's map of 1820 marks the 'Gallow Muir' near Bogside. The name suggests that this was the site of the Gallows, probably linked with the medieval right of 'Pit & gallows', held by the Lord of the Barony. This right was removed in 1747. In 1813, 31 unemployed men were given work levelling the Gallows Knowe at the muir prior to the construction of the new Academy. The wooden base of the gallows and several other associated finds were made.[154]

In woodland near to the near the Doura Burn at North Millburn is a glacial erratic boulder. Such boulders were usually broken up by farmers and such a rare survival as this, is one more indicator that the site may be a genuine ancient woodland.[155]

The A 78 (T) and B7080 are partially built on the old estate's 'Long Drive' carriageway to Stanecastle. The road from the Eglinton interchange to the Hill roundabout and onwards towards Dreghorn has been named 'Long Drive'.

A piggery was built at the park before it was purchased by the local authority. A few of its buildings survive.

£100,000 was spent by the Montgomeries on creating Ardrossan's harbour and they intended to make it the principal port for Glasgow. Construction of the Glasgow, Paisley and Johnstone Canal began in 1807 and the first boat, the passenger boat, The Countess of Eglinton, was launched in 1810; completion to Glasgow's Port Eglinton from Paisley was achieved in 1811, but the section to Ardrossan was never built.[156] The Head gardener at Eglinton Castle laid out the policies and gardens at Spier's school, Beith in 1887.[157]

HMS Eglinton was a World War II Hunt Class escort Destroyer built by Vickers Armstrong of Newcastle and launched on 28 December 1939. A previous HMS Eglinton was a World War I minesweeper; both were named after the Eglinton Foxhunt.[158]

A Gauging station operated by SEPA is located just above the weir on the Lugton Water at the suspension bridge; it appears as a small building and a set of cables and wires stretched across the river.

Lady Frances Montgomerie was buried at Hollyrood Abbey in Edinburgh on 11 May 1797. She was the daughter of Archibald, 12th Earl of Eglinton.[159]

At the coronation of Charles I at Holyrood the Earl of Eglinton had the honour of bearing the king's spurs.[160]

Glasgow University's Eglinton Arts Fellowship was established in 1862 by subscription to commemorate the public services of Archibald William, 13th Earl of Eglinton, Rector of the University 1852–54.[161]

See also

[edit]- Annick Lodge

- Barony and Castle of Giffen A Montgomerie possession.

- Bourtreehill house

- Clearance cairn

- Clyde Muirshiel Regional Park

- Lands of Doura

- Drukken Steps

- Industry and the Eglinton Castle estate

- Eglinton Tournament bridge

- Girdle Toll

- River Irvine

- Robert Burns and the Eglinton Estate

- Susanna Montgomery, Lady Eglinton

- Auchans, Ayrshire

References

[edit]Notes;

- ^ Bridle paths within Eglinton Country Park.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Landscape of the Knights, page 27.

- ^ Eglinton Fishing Forum Archived 29 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved : 2011-08-14

- ^ "The Eglinton to Irvine via Dreghorn cycleroute". Archived from the original on 8 June 2007. Retrieved 10 September 2007.

- ^ a b General Roy's Maps.

- ^ "Bird Records". Archived from the original on 9 February 2008. Retrieved 10 September 2007.

- ^ Kidsneuk Motte pottery

- ^ Simpson, page 23.

- ^ RCAHMS. Kidsneuk. NMRS: NS34SW7.

- ^ a b Dobie.

- ^ a b c Ness, Page 29.

- ^ Robertson, page 205.

- ^ Love, page 11.

- ^ Leighton, Facing page 229.

- ^ Sanderson, page 18.

- ^ a b c d e f Eglinton archive, Eglinton Country Park archive.

- ^ a b Groome, page 530.

- ^ a b Dowells Ltd. Catalogue of the Superior Furnishings, French Furniture, etc. Tuesday, 1 December 1925, and Four following days.

- ^ Aikman.

- ^ Love, Dane (2005), page 35.

- ^ a b Eglinton Castle history

- ^ Campbell, Page 177

- ^ Barr, Allison (2008), Five Roads / Corsehillhead resident.

- ^ Sharp, page 32.

- ^ a b Janet McGill (2008) of Auchenwinsey Farm. Oral information.

- ^ Aitken.

- ^ a b c Aiton.

- ^ Millar, page 74.

- ^ "Blairquhan Castle. Accessed: 2009-12-24". Archived from the original on 1 November 2012. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

- ^ Ayrshire. A Survey of Gardens and Designed Landscapes. Peter MCGowan Associates with Christopher Dingwall. March 2007.

- ^ Leighton, page 229.

- ^ Stoddart, page 313.

- ^ National Archives of Scotland. RHP35796/1-5.

- ^ Kilwinning Past & Present. Section 3.7

- ^ a b c d e f Eglinton Archive, Eglinton Country Park

- ^ Millar

- ^ Paterson, Pages 431 - 432

- ^ a b c d Scottish National Archive. RHP 2027.

- ^ a b Historic gardens

- ^ Montgomeries of Eglinton, page 94.

- ^ King, Robert (2009). Oral Communication.

- ^ National Archives of Scotland. RHP3 / 37.

- ^ a b Edinburgh Croquet Club Archived 10 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved : 2011-04-04

- ^ Eglinton Archive, Eglinton Country Park - falconer

- ^ Swan, page 19.

- ^ Ayrshire History Website

- ^ Eglinton Archives, Eglinton Country Park

- ^ Millar.

- ^ Historic Alloway, page 11.

- ^ Eglinton Archive

- ^ Robertson, page 126.

- ^ Ashford, P. K. (1994). Eglinton Archive, Eglinton Country Park

- ^ Millar, page 74

- ^ Robertson (1820).

- ^ Heather House, Troon. Accessed : 2009-12-11

- ^ Lilliput Lane - Scottish models. Accessed : 2009-12-11

- ^ Robertson (1820), Page 41.

- ^ a b c Montgomeries of Eglinton.

- ^ Buxbaum, page 7.

- ^ Ness, page 24.

- ^ Montgomeries of Eglinton, page 102.

- ^ Hansell, page 4.

- ^ Service (1890), Page 24

- ^ Landscape of the Knights, page 16.

- ^ National Archives of Scotland. Eglinton Papers. GD3.

- ^ Close (2012), Page 391

- ^ Armstrong.

- ^ Landscape of the Knights, page 17.

- ^ Fawcett, page 20.

- ^ a b Landscape of the Knights, page 31.

- ^ Robertson, page 49.

- ^ Paterson, V. III - Cunninghame, page 490.

- ^ a b Eglinton archives, Eglinton Country Park.

- ^ Douglas, page 228.

- ^ Robertson, pages 342 - 346.

- ^ Smith, Page 59.

- ^ The Feud between the Montgomeries and the Cunnighames of Glencairn Archived 12 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Robertson (1889), pages 15 & 16.

- ^ Clan Montgomery Society, Page 6

- ^ Paterson, V. IV. - I - Cunninghame, page 287.

- ^ Daniel, page 66.

- ^ The Eglinton Tournament, page 5.

- ^ 'The Queen's Champion'.

- ^ Alloway

- ^ Anstruthers, page 189.

- ^ Paterson (1871), pages 163 - 184

- ^ Montgomeries of Eglinton, page 87.

- ^ a b Eglinton Fair. Page 2

- ^ Earl of Beaconsfield, pages 256 - 270.

- ^ Rooter or Ripper Retrieved : 2011-03-15

- ^ a b McClure, page 53.

- ^ "The Polnoon Estate". Archived from the original on 5 December 2008. Retrieved 23 January 2008.

- ^ Landscape of the Knights, Page 18.

- ^ Kilwinning Past & Present, Section 4.4

- ^ Kilwinning Past & Present, Section 3.7

- ^ Landscape of the Knights, page 12.

- ^ Sharp, page 5.

- ^ Landscape of the Knights, page 5.

- ^ Sharp, page 6.

- ^ Wilson, James (2008). Eglinton Archives - Written correspondence.

- ^ Jardine, pages 288 - 295.

- ^ Archaeol. Scot., page 57.

- ^ MacDonald, page 51

- ^ Smith, page 60.

- ^ a b "RCAHMS Canmore site". Archived from the original on 23 December 2012. Retrieved 10 September 2007.

- ^ Billings, Plate 41.

- ^ Smith.

- ^ Video footage of Lawthorn Mount and its links with the Barony of Stane.

- ^ Service, page 190.

- ^ Kennedy, James (1969) The Inquirer, Vol. 1. No. 5.

- ^ Strawhorn Page 18

- ^ McJannet, Page 276

- ^ Strachan, Page 2

- ^ Landscape of the Knights.

- ^ Landscape of the Knights, page 14.

- ^ Montgomeries of Eglinton, page 107.

- ^ a b Ness.

- ^ Sharp, page 36.

- ^ Clinton, page 38.

- ^ Warrack.

- ^ Ker, page 161.

- ^ Old Maps held by the National Library of Scotland

- ^ Smith, page 61.

- ^ James Ness papers. North Ayrshire Local & family history centre, Irvine.

- ^ Kilwinning, page 21

- ^ Ker page 161

- ^ Rackham, pages 147 - 148.

- ^ Warrack

- ^ Ker, page 153.

- ^ Ker, page 151.

- ^ Ker.

- ^ Paterson, Page 504.

- ^ Kilwinning 2000, page 36.

- ^ Love, page 61

- ^ McLure, page 53.

- ^ Irvine Herald.

- ^ Strawhorn, page 33.

- ^ Muniments, Page 161

- ^ New Zealand place names.

- ^ Pride, page 141.

- ^ Service.

- ^ Service, pages 81 - 83.

- ^ Service, page 48.

- ^ Love (2009), Pages 187-188

- ^ Earls of Eglinton. Ref. GD3. National Archives of Scotland.

- ^ Ardrossan Academy website.

- ^ Strawhorn, page 125.

- ^ a b Montgomeries of Eglinton, page 98.

- ^ a b Service, Pages 19 - 22

- ^ Montgomeries of Eglinton, page 69.

- ^ Montgomeries of Eglinton, page 63.

- ^ Thomson.

- ^ Personal communication to George Clark, Manager, Eglinton Country Park. 1989.

- ^ "Historic guide to Irvine". Archived from the original on 16 September 2007. Retrieved 28 September 2007.

- ^ Muir, pages 91 - 92.

- ^ Robertson.

- ^ The Old Spierian, page 5.

- ^ HMS Eglinton[permanent dead link]

- ^ Daniel, page 199.

- ^ Daniel, page 111.

- ^ Glasgow University Art's Fellowship. Archived 11 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine

Sources;

- Aikman, J & Gordon, W. (1839) An Account of the Tournament at Eglinton. Edinburgh: Hugh Paton, Carver & Gilder.

- Aiton, William (1811). Extract from the General View of the Agriculture of Ayr.

- Anstruther, Ian (1986) The Knight and the Umbrella. Pub. Alan Sutton. ISBN 0-86299-302-4.

- Archaeol Scot (1890). 'List of donations presented to the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland'. Archaeol Scot, 5, 3, 1861–80.

- Armstrong and Son. Engraved by S. Pyle (1775). A New Map of Ayr Shire comprehending Kyle, Cunningham and Carrick.

- Buxbaum, Tim (1987) Scottish Doocots. Pub. Shire Album 190. ISBN 0-85263-848-5.