Wapping Tunnel

Eastern portal in the Cavendish Cutting in 1831. The Wapping tunnel is the centre tunnel. The right hand tunnel is to the Crown St terminal Station | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Other name(s) | Edge Hill Tunnel |

| Location | Edge Hill railway station, Liverpool |

| Operation | |

| Opened | 1830 |

| Closed | 1972 |

| Traffic | Liverpool-Manchester line |

| Route map | |

Map of south Liverpool with the Wapping Tunnel shown in red, ventilator towers represented by yellow dots | |

Wapping or Edge Hill Tunnel in Liverpool, England, is a tunnel route from the Edge Hill junction in the east of the city to the Liverpool south end docks formerly used by trains on the Liverpool-Manchester line railway. The tunnel alignment is roughly east to west. The tunnel was designed by George Stephenson with construction between 1826 and 1829 to enable goods services to operate between Liverpool docks and all locations up to Manchester, as part of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway.[1] It was the first transport tunnel in the world to be bored under a city.[2] The tunnel is 2,030 metres (1.26 mi) long, running downhill from the western end of the 262 metres (860 ft) long Cavendish cutting at Edge Hill in the east of the city, to Park Lane Goods Station near Wapping Dock in the west. The Edge Hill portal is near the former Crown Street Station goods yard. The tunnel passes beneath the Merseyrail Northern Line tunnel approximately a quarter of a mile south of Liverpool Central underground station.

History

[edit]Liverpool is built on an escarpment running down to the River Mersey. The original proposal for the railway out of Liverpool was a route north along the docks and riverbank. This route proved problematic with local landowners. The new route entering the city centre from the east required considerable engineering works in addition to the tunnel. The 1-in-48 gradient of the tunnel was much too steep for the power of the steam locomotives of the day. A large stationary steam engine was installed at the Cavendish cutting at Edge Hill in a short tunnel bored into the rock face on the side of the cutting, near a decorative Moorish Arch spanning the cutting. Goods wagons were hauled by rope up from the Park Lane goods station at the south end docks. The goods wagons were hitched to locomotives at the Edge Hill junction for the continuing journey to all locations from Liverpool to Manchester. The tunnel opened in 1830 and closed on 15 May 1972.

The dockside portal to the tunnel is clearly visible on Kings Dock Street. This was the middle of three short exit tunnels at the western end, which met in a short open ventilation cutting between Park Lane and Upper Frederick Street. The quoted length of 2,030 metres (6,660 feet) includes both the main tunnel and the short exit tunnel.

The Edge Hill entrance is still open to the atmosphere, but is not accessible to the public. The portal is the central of three tunnels at the western end of the Cavendish cutting. The right hand tunnel is the original 1829 tunnel into Crown Street Station. The left hand tunnel is the later 1846 tunnel into the Crown Street goods yard. This tunnel currently has tracks, for use as a headshunt and locomotive run-round for goods trains. However, artwork from before the third tunnel was constructed shows that a portal was already present from the outset[citation needed] - this was purely for architectural symmetry and is, in fact, a store room.

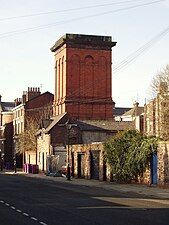

Other visible evidence of the tunnel still exists, in the form of three imposing red-brick ventilation towers. One is on the landscaped park between Crown Street and Smithdown Lane, one on Blackburne Place (illustration), and one close to Grenville Street South. There were at least two others that were later demolished, one adjacent to Great George Street, and one by Myrtle Street.

- The derelict tunnel today

-

Eastern portal in the Cavendish Cutting today. The tunnel is the middle portal of three. The portal to the right is obscured by undergrowth.

-

A tunnel ventilation shaft on Blackburne Place

-

Inside of Tunnel from Kings Dock Street. The light seen is from an air shaft

-

Tunnel portal at Kings Dock Street at the western end

Plans for partial reinstatement of tunnel

[edit]In the 1970s, during planning work for the Merseyrail underground in Liverpool city centre, there were two proposals to use parts of the Wapping Tunnel or Waterloo Tunnel (Victoria Tunnel) to connect Liverpool Central underground station and Edge Hill junction. During the construction of the Merseyrail network in the 1970s a part of the new tunnel south out of Central Station passed over the Wapping Tunnel at right angles. The new tunnel dropped into the upper part of the Wapping tunnel reducing its height.[3] This would require lowering the floor of the tunnel at this point to allow trains to pass. When the junction on the Northern Line tunnel south of Central station was built in the late 1970s, two header tunnels were constructed to cater for branching into the Wapping Tunnel.[4]

In May 2007 it was reported that chief executive of Merseytravel, Neil Scales, had prepared a report outlining the possibilities for reuse of the tunnel.[5][6] The November 2016 refresh of Mersytravel's Long Term Strategy references a "Wapping Tunnel Scheme" in Network Rail's CP7 period.[7] Merseytravel hope to re-use the tunnel to create new underground connections into burrowing junctions south of Liverpool Central station on the Northern Line to allow trains to run between Central station and Edge Hill station and beyond.[8]

Merseytravel commissioned a feasibility study into the re-opening of the tunnel which was completed in May 2016. The study was focused on using the Wapping Tunnel to connect the Northern and City Lines together and the possible creation of a new station along the route to serve the city's Knowledge Quarter. The report found that the Wapping Tunnel was in good condition though suffered from flooding in places and would require some remedial work, however the concept of re-opening the tunnel was viable.[1]

Accidents and incidents

[edit]- 28 September 1907, Brakesman John Fairbrother, was working a train to the docks. The train stopped in the tunnel and as Fairbrother went to lift some of the wagon brakes he slipped bruising his back and knees. While he was not injured further, lifting the brakes caused the train to descend uncontrollably down the tracks damaging 13 wagons and 4 brake vans.[9]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "City Line to Northern Line Connection Feasibility Study" (PDF). Merseytravel. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ^ "Wapping and Crown Street Tunnels". Engineering Timelines. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- ^ "Subterranea Britannica: Sites: Wapping Tunnel". Subbrit.org.uk. Retrieved 3 September 2015.

- ^ Maund, T.B. (2001). Merseyrail electrics: the inside story. Sheffield: NBC Books.

- ^ Coligan, Nick (17 July 2006). "The trams are dead, long live the train". icLiverpool. Retrieved 10 September 2008.

- ^ Nield, Larry (30 May 2007). "Plan to reopen railway tunnels". icLiverpool. Retrieved 10 September 2008.

- ^ "Merseytravel Committee Rail Development and Delivery" (PDF). Merseytravel. Merseytravel. Retrieved 7 December 2016.

- ^ Liverpool City Region Combined Authority. "Long Term Rail Strategy" (PDF). Retrieved 4 November 2017.

- ^ Esbester, Mike (5 September 2022). "Listed accidents". Railway Work, Life & Death. Retrieved 23 April 2024.

External links

[edit] Media related to Wapping Tunnel, Liverpool at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Wapping Tunnel, Liverpool at Wikimedia Commons- Subterranea Britannica: Liverpool - Edge Hill Cutting & Tunnels

- Engineering Timelines