East Pakistan Air Operations (1971)

This article's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Wikipedia. (April 2012) |

| East Pakistan Air Operations | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Bangladesh Liberation War | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

Gp. Capt. A.K. Khandker Air Mshl Hari Chand Dewan |

Air Cmde Inamul Haque Khan Lt. Col. L.A. Bukhari | ||||||||

| Units involved | |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

3 MiG-21 FL Squadrons |

16 Canadair Sabre | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

Indian Claims 23 Indian warplanes shot down by PAF and Anti-Aircraft guns[4] |

3 Sabres lost in air combat, 23 aircraft lost altogether 1 helicopter shot down or abandoned[3][5] | ||||||||

| Hundreds killed in Indian attack on an Orphanage in Dacca[6] | |||||||||

East Pakistan Air Operations covers the activity of the Pakistan Air Force (PAF) and Pakistan Army Aviation units in former East Pakistan during the Bangladesh Liberation War. The operations involved the interdiction, air defense, ground support, and logistics missions flown by the Bangladesh Air Force, Indian Air Force, and the Indian Navy Aviation wing in support of the Mukti Bahini and later Indian Army in Bengal.

The Indian Air force aided the Mukti Bahini in organizing the formation of light aircraft (called Kilo flight). They were manned and serviced mainly by Bengali pilots and technicians who had defected from the Pakistani Air Force.[7]

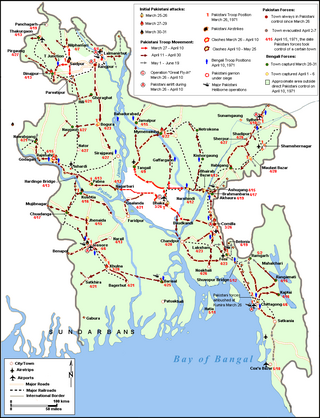

This unit launched attacks on targets in Bangladesh on December 3, 1971, prior to the start of formal combat between India and Pakistan. The first of the engagements between the opposing air powers occurred before the formal declaration of hostilities. Indian Air units commenced operations on 4 December 1971 in the eastern theater. By 7 December 1971, Tejgaon airport was put out of operation thereby grounding the PAF in East Pakistan. Indian units and Kilo Flight continued flying missions over Bangladesh until the unconditional surrender of Pakistani forces to joint Bangladeshi and Indian forces command on 16 December 1971.

Eastern Theater: historical background

[edit]East Pakistan saw no air combat, during the Indo-Pakistani War of 1947, even though both countries possessed functional air forces. Pakistan had concentrated most of its military assets in West Pakistan,[8] and the Indian war effort were concentrated on the Western front as well. India began upgrading its air capabilities on its eastern border only after the war.

In 1958, the Eastern Operational Group was formed in Kolkata and it was upgraded into a Command the following year. Following the Sino-Indian War of 1962, the Eastern Air Command Headquarters shifted to Upper Shillong, and extensive efforts to increase its operational capabilities in terms of the number of squadrons and modernization of its warplanes and operational infrastructure began, as the added emphasis was given to countering any possible Chinese threat.[citation needed]

In contrast, Dhaka airfield at Tejgaon was activated only in 1949, and a squadron of Hawker Fury planes was stationed there in 1956. The PAF posted a squadron of F-86 Sabres in East Pakistan in 1963, which was replaced by No 14 Squadron in 1965,[9] while the Air Force infrastructure development in the province was largely ignored. The Indian Air Force had six combat squadrons posted under its Eastern Air Command by 1965.[10]

1965 Indo-Pakistani War: Eastern Theater

[edit]The air forces of both countries launched attacks against each other's bases in the eastern theater, as soon as hostilities commenced in September 1965. The IAF bombed airfields and airstrips located in East Pakistan (at Chittagong, Dhaka, Lalmunirhat Airport, and Jessore),[citation needed] while the PAF managed to launch two celebrated raids on the Indian Air Force base at Kalaikunda, near Kharagpur, in West Bengal.[11] The PAF raids, a five-plane strike which had achieved total surprise, was followed up by a four-plane attack, which was opposed by Indian Interceptors, took place on 7 September, destroying several English Electric Canberra bombers and de Havilland Vampire aircraft on the ground,[12] while the IAF claimed 2 aerial kills (Pakistani sources record 1 F-86 lost). The PAF also launched attacks on Bagdogra on 10 September and Barrackpore on 14 September, with varying results. The IAF hit back with more airstrikes on Dacca, Jessore, and Lalmonirhat Airport, these failed to destroy any aircraft. Mid-air interceptions and dogfights rarely happened, and barring some skirmishing between the EPR and BSF along the border, the air forces of both countries were responsible for most of the combat activity in the eastern theater during the 1965 war. The final tally was 12 Indian aircraft destroyed on the ground (PAF claim 21 aircraft destroyed),[citation needed] 2 Pakistani Sabres shot down,[13] (the PAF records one aircraft lost), and 1 PAF Sabre lost due to an accident.[14] Following the war, the IAF continued its steady growth in combat capacity and logistical capabilities, while Pakistan boosted its squadron strength to 20 Canadair F-86 Sabres (although it neglected to expand its operational infrastructure substantially).

PAF during Operation Searchlight in 1971

[edit]PAF had sixteen Canadair Sabre (No 14. Squadron OC Wing Commander Muhammad Afzal Chawdhary), two T-33 trainers, and two Aerospatiale Alouette III helicopters stationed in East Pakistan,[15] while "Log Flight" of Army Aviation Squadron No. 4 under Major Liakat Bhukhari contained two Mil Mi-8 and two Alouette III helicopters.[16] PAF operational effectiveness suffered to some degree because all Bengali pilots and technicians (about half of the 1222 PAF personnel in East Pakistan) had been grounded during the political unrest of March 1971.[17][18] Air Commodore Mitty Masud commanded the PAF detachment in East Pakistan. When Operation Searchlight was launched to quell the Awami League-led political movement, the PAF contribution was crucial to its success. No. 4 Army Aviation squadron's full contingent of six Mil Mi-8 and six Alouette III helicopters were stationed in Dacca on 14 April,[7] commanded by Lt. Col. Abdul Latif Awan. The PAF also requisitioned and rigged with light weapons numerous cropdusters and other light civilian aircraft to augment its reconnaissance and ground attack capabilities.[7]

Operation Great Fly-In

[edit]Pakistan Eastern Command had planned an operation named "Blitz" in February 1971 to counter the Bengali political movement, and the 13th Frontier Force and 22nd Baluch battalions had arrived in East Pakistan from Karachi[19][16] between 27 February and 1 March 1971, via PIA aircraft, before the Pakistani Air Force took over Tejgaon Airport administration[20] as part of the newly planned operation. After the decision to launch Operation Searchlight was made, the Pakistan High Command decided to reinforce the 14th Infantry Division in East Pakistan with the 9th and 16th Infantry Divisions after the start of the operation. These divisions began preparing for the move after 22 February 1971, and military personnel began arriving in East Pakistan via PIA and Air Force planes. Because India had banned overflights starting 20 January 1971, all Pakistani planes had to detour to Sri Lanka during trips between East and West Pakistan.

Pakistan Air Force No. 6 Squadron had nine Hercules C-130B/E transport aircraft available in March 1971. Pakistan employed five C-130Bs[16] as well as 75% of PIA transport capacity (The PIA fleet contained seven Boeing 707 and 4 Boeing 720 planes in 1971) to ferry troops from West Pakistan 1971.[21] Two entire infantry divisions were airlifted to East Pakistan from West Pakistan between 26 March and 2 May in an operation dubbed Great Fly-In.[22] Moving two entire infantry divisions - which were sorely needed to bolster the army in East Pakistan then facing stiff opposition over a span of two weeks - was a vital factor in sustaining the operation of the Pakistan Army in East Pakistan.

Between, 25 March and 6 April 1971, two Division Headquarters (9th and 16th), with the five Brigade Headquarters, (the 205th, 27th, 34th, 313th and 117th Brigades), along with one commando and twelve infantry battalions were moved to East Pakistan through the air.[23] Between 24 April and 2 May another three infantry battalions, along with two heavy mortar batteries, two wings each of East Pakistan Civil Armed Force and West Pakistan Rangers, and a number of North West Frontier Scouts, were re-positioned as well.[23] After 25 March, two C-130B planes were stationed in Dhaka to link the areas under Pakistani control in East Pakistan with Dhaka and also ferry fuel from Sri Lank and Myanmar.

PAF Operations during Operation Searchlight

[edit]Air Commodore Mitty Masud had opposed Operation Searchlight on moral grounds in a meeting of Pakistani Senior officers on 15 March[24] and then had refused requests from Army to commence airstrikes against civilians on 29 March.[25][26] He also assured Bengali PAF staff of their personal safety on 27 March and on 30 March gave them the option of declining missions or going on leave but also warned them to refrain from treason.[25][26]

After 26 March, Pakistani Army was initially confined to a handful of bases across the province, with control over airports near Jessore, Chittagong, Comilla, and Salutikar near Sylhet. Helicopters and C-130 transport planes also ferried troops and munitions to army bases cut off and surrounded by the Mukti Bahini. Helicopters were used to carry munitions from Gazipur District to Dhaka, evacuate wounded, [citation needed] and carry personnel between bases.[27] Army helicopters failed to evacuate 25 Punjab company under Major Aslam from Pabna on 28 March, and the company was almost annihilated,[28] while due to poor visibility, no airstrikes were sent to help the 27 Baloch company in Kushtia, which was also wiped out.[29] Helicopters initially failed to locate the 53rd Brigade column held up at Kumira, but flew in munitions/supplies for the 20th Baluch in Chittagong, evacuated wounded and ferried SSG commandoes including the 2nd SSG battalion (CO: Lt. Col. Sulayman) to Chittagong on 26 and 27 March to aid the Pakistani column held up at Kumira by EPR troops.[30][31] The attempt failed, the CO and several commandos were killed.

Ground support and airlifts

[edit]

On 31 March, Air Commodore Inamul Haque Khan took over as AOC East Pakistan from Masud, who was relieved of his post. EPR positions in Chittagong were bombed on 30 and 31 March,[32] the Kalurghat Radio station, which was used to transmit the declaration of Independence, became inoperable following airstrikes on 31 March,[32][33] and PAF airstrikes preceded the successful 31 Punjab attack on Shamshernagar Airport, which was held by EPR 12 Wing, on 31 March[34] and EPR 6 wing formations were bombed at Godagari prior to 25 Punjab probing attack on 30 March.[35][36] On 1 April, the PAF flew sorties to aid the 23rd Field Artillery contingent at Bogra, however, the town eventually fell to Bengali forces.

Army Aviation helicopters flew in supplies and reinforcements and evacuated wounded between 1 and 6 April from the besieged 25 Punjab Battalion in Rajshahi as PAF jets covering the helicopters bombed Mukti Bahani positions, and PAF also struck the 2nd and 4th EBR and EPR positions around Brahmanbaria, Ashuganj, Bhairab and other areas located between Sylhet and Comilla during the same time span.[37][38] On 3 April areas around Pabna[26] and Chuadanga were bombed, causing civilian casualties.[32][39]

Pakistan Army Aviation Helicopters ferried 4 FF and 48 Punjab detachments to Rangpur cantonment between 30 March and 1 April. 4 FF captured Lalmonirhat Airport on 4 April, aided by PAF bombing of EPR positions after the initial attack was repulsed on 2 April.[40][33] Airstrikes hit EPR positions at Khadimnagar and Lalakaji, north of Sylhet and also scattered EPR troops advancing towards Dhaka from Narshindi on 6 April,[41] while PAF C-130 planes, PIA aircraft and Army aviation helicopters began to transport 313 brigade troops to Sylhet Airport,[42] 117 Brigade troops to Comilla, while 53rd Brigade staff along with 9th division staff and Maj. Gen. Shawkat Riza was flown to Chittagong, who assumed command of the 9th division brigades located in Sylhet, Comilla and Chittagong.[citation needed] After 6 April, Jessore Cantonment was also reinforced through the air and the city was occupied by Pakistan Army. The Mukti Bahini detachment advancing towards Jessore from Narail scattered into small groups after PAF jets bombed them.[43]

Maj. Gen. Rahim Khan assumed command of the 14th Division and tasked the 27th brigade to clear the area north of Dhaka and the 57th brigade (CO Brig. Jahanzeb Arbab) moved towards Rajshahi. 22nd Balouch advanced towards Narshindi on 6 April, and although held up for two days by EPR troops, eventually broke through with the help of PAF bombing runs on 9 April.[44] PAF jets also hit EPR positions at Khadimnagar, north of Sylhet and also to the South of Surma River before 313 Brigade troops drove Bengali troops from both positions on 10 April, while Chuadanga was heavily bombed after Akashbani reported the town as the temporary capital of the Bangladesh Provisional Government.[45] PAF struck Bengali troop positions near Bhairab before the army commenced their attack, and 2 Mi-8 helicopters dropped SSG troops behind Bengali lines under cover of PAF sorties, resulting in the capture of Bhairab bridge.[33] 27th Brigade next assaulted Bengali troops around Ashuganj and Brahmanbaria, 6 PAF Sabers bombed the areas[46][47] and flew cover before Army Aviation helicopters dropped troops behind Bengali positions on 15 April, and occupied these areas by 19 April.

57th Brigade moved toward Rajshahi on 8 April, crossed the Padma aided by PAF Sabres, which struck Nagarbari crossing on 11 April, and bombed Bengali positions around Rajshahi on 13 and 14 April. After the 57th Brigade occupied Rajshahi, Bengali troops reformed at Godagari and Nawabganj, where they were bombed on 16 and 17 April, by the PAF before Pakistan Army forced them to retreat across the border,[48] while Bengali positions around Jessore were also bombed on 16 April before the Pakistani Army retreated from the city. On 17 April PAF severely bombed on Gaffargaon town in weekly bazar day which resulted the killing of 14 civilians and wounded around 150.[citation needed]

Barisal was bombed by PAF on 17 April,[49] and, the PAF participated in Operation Barisal by bombing Bengali positions in Barisal and Patuakhali on 25 and 26 April respectively while Four MI -8 and two Alouette helicopters airdropped SSG Commandos near the towns[50] before Naval ships landed Army detachments from 6th Punjab and 22nd Frontier Force Regiments to occupy the towns. PAF airstrikes and 313th Brigade attacks had driven Bengali soldiers from their positions at Khadimnagar, and as they reformed at Haripur, PAF sorties on 20 April caused them to retreat across the border. Chandpur fell to river borne troops after Sabres bombed Bengali positions near the city on 20 April. After Mukti Bahini Sector 1 and Sector 2 troops repulsed 20 Baloch and 24 FF attacks on Belonia, a small strip of land surrounded on three sides by Indian territory, PAF Sabres, which had refrained from hitting Bengali positions fearing violations on Indian airspace, launched strikes while Army Aviation heli-dropped commandos at night behind Bengali positions on 17 June, and again on 18 June, forcing Mukti Bahini across the border.[51][52] With the Fall of Belonia, Mukti Bahini control shrunk to a few border enclaves and they shifted to waging guerrilla warfare against the occupying forces.[51]

The PAF had enjoyed total air supremacy during March – October as the Mukti Bahini lacked both planes and air defense capability to counter their efforts, and flew 100 to 170 sorties[53] in support of the army over this period. Pakistani forces had defeated the Bengali resistance by mid-May 1971, and had occupied the entire province by June 1971.[54][23] PAF activity decreased with the advent of Monsoon and the Mukti Bahini operations switched from conventional war to guerilla warfare after June.

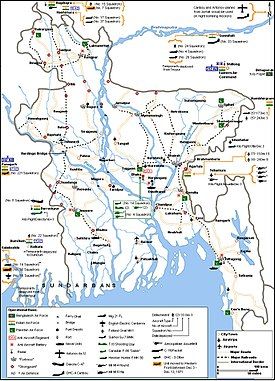

Mukti Bahini Airforce/ Bangladesh Air force : Kilo Flight

[edit]The Indian Army was helping the Mukti Bahini, through Operation Jackpot, since May 1971, while the Indian Navy had helped set up the Bengali Naval commando unit and had provided command staff for the Bengali gunboats, which were busy mining riverine craft and harassing merchant marine operations in East Pakistan. The IAF had flown reconnaissance flights over East Pakistan since June 1971, but could not come to grips with the PAF, until formal hostilities commenced. Nine Bengali pilots (Three former PAF and six civilian pilots) and fifty technicians - formerly of the PAF and serving with the Mukti Bahini in various capacities - were gathered for a special mission on 28 September 1971 at Dimapur in Nagaland.[55]

Indian civilian authorities and the IAF donated 1 DC-3 Dakota (given by the Maharaja of Jodhpor), 1 DHC-3 Otter plane, and 1 Alouette III helicopter for the newborn Bangladesh Air Force, which was to take advantage of the lack of night-fighting capability of the PAF to launch hit-and-run attacks on sensitive targets inside Bangladesh from the air. The Bengali rank and file fixed up the World War II vintage runway at Dimapur, then began rigging the aircraft for combat duty. The Dakota was modified to carry 500 pound bombs, but for technical reasons it was only used to ferry Bangladesh government personnel. Captain Abdul Khalque, Captain Alamgir Satter, and Captain Abdul Mukit, all destined to earn the Bir Pratik award, piloted the Dakota.

The helicopter was rigged to fire 14 rockets from pylons attached to its side and had .303 Browning machine guns installed, in addition to having 1-inch (25 mm) steel plate welded to its floor for extra protection. Squadron Leader Sultan Mahmood, Flight Lieutenant Badrul Alam, and Captain Shahabuddin Ahmed, all of whom later won the Bir Uttom award, operated the helicopter. The Otter boasted 7 rockets under each of its wings and could deliver ten 25 pound bombs, which were rolled out of the aircraft by hand through a makeshift door. Flight Lt. Shamsul Alam, along with Captains Akram Ahmed and Sharfuddin, flew the Otter - all three were later awarded Bir Uttam for their service in 1971. This tiny force was dubbed Kilo Flight, the first fighting formation of the nascent Bangladesh Air force.[56][57]

Under the command of Group Captain A.K. Khandkar and Flight Lieutenant Sultan Mahmud, intense training took place in night flying and instrumental navigation. After 2 months of training, the formation was activated for combat. The first sortie was scheduled to take place on 28 November, but was moved back 6 days, to 2 December 1971.[58] The Otter - flown by Flight Lt. Shamsul Alam, with co-pilot F.L. Akram - was moved to Kailashsahar, and was prepared for a mission against targets in Chittagong. The helicopter, piloted by Flight Lt. Sultan Mahmood and Flight Lt. Badrul Alam, was to hit Narayangang, flying from Teliamura.[59][60]

IAF Eastern Command in 1971

[edit]The Central Air Command was headquartered at Allahabad (OC: Air Vice Marshal Maurice Baker) and the Eastern Command (OC: Air Marshal Hari Chand Dewan) was headquartered in Shillong,[61] so an advanced headquarters was created at Fort William to better coordinate matters after a consultation with Lt. Gen. Jacob, COS Army Eastern Command.[62] Four tactical air command units were attached to the three army corps headquarters and 101 Communications Zone.[63] The Air Force had nine air defence regiments organized into were two air defense brigades (No. 342, HQ Panagarh and No. 312, HQ Shilliog) and three S-75 Dvinas surface-to-air missile squadrons in the east.[64]

Eastern Air Command Order of Battle 1971

[edit]

Western Sector:[65] (Operating on the west of Jamuna river)

- No. 22 Squadron (Swifts): Folland Gnat MK 1 Kalaikudda, then Dum Dum, (WC Sikand)

- No. 30 Squadron (Charging Rhinos): Mig 21 FL — Kalaikudda (WC Chudda) - Fighter Interceptor – moved to Chandigarh on 5 December.

- No. 14 Squadron (Bulls): Hawker Hunter F. MK 56 – Kalaikudda, then Dum Dum (WC Sundersan) - Fighter

- No. 16 Squadron (Rattlers): Canberra - Kalaikudda then Gorakhpur - (WC Gautum) - Bomber

- No. 221 Squadron (Valiants): Su-7 BMK – Panagarh (WC A. sridharan) - Fighter/Bomber. The squadron was redeployed to Ambala on 12 December 1971.

- No. 7 Squadron (Battle Axes): Hawker Hunter F. MK 56 and 2 F. MK 1 - Bagdogra (WC Ceolho, then WC Suri). The squadron was moved to Chamb after 12 December.

- No. 112 (Aérospatiale Alouette III) Helicopter unit

North East and North Western Sector:[65] (Areas to the East of Jamuna River)

CO: Air Vice Marshal Devasher Headquarters: Shillong

- No. 17 Squadron (Golden Arrows): Hawker Hunter F MK 56 - Hashimara (WC Chatrath)

- No 37 Squadron (Black Panthers): Hawker Hunter F MK 10 - Hashimara (WC Kaul)

- No. 4 Squadron (Oorials): Mig 21 FL Gauhati less one flight redeployed from Tezpur (WC JV Gole)

- No. 24 Squadron (Hunting Hawks): Folland Gnat less one flight Gauhati redeployed from Tezpur (WC Bhadwar)

- No. 15 Squadron (Flying Lancers): Folland Gnat — Bagdogra then Agartala (WC Singh)

- No. 28 Squadron (First Supersonics): Mig 21FL less two flights Gauhati (Wing Commander B K Bishnoi) redeployed from Tezpur

- No. 110 (Mi-4,) 105 (Mi-4) – Kumbhirgram, No. 111 (Mi-4) – Hahsimara, 115 (Alouette III) Helicopter Squadrons — Agartala all redeployed to Teliamura.

Transport and airlift operations were to be handled by three Douglas C-47 Dakota squadrons, two Antonov – 12, one DHC-4 Caribou, one DHC-3 Otter and one C-119 Packet squadrons assembled from Western, Central and Eastern Commands and based at Jorhat, Guahati, Barrackpur and Dum Dum during 3–16 December 1971.

Aided by the intelligence provided by Bengali PAF officers who had joined the Mukti Bahini,[66][67] the Eastern Air Command planned to achieve total air dominance by destroying the Sabres of No. 14 Squadron, defend Indian forces from the PAF, and support ground operations.[68] The IAF also made plans to counter any Chinese incursions into Indian territory, but the Chinese remained militarily inactive in 1971.

INS Vikrant, which had three squadrons, the INAS 300 "White Tigers" flying Hawker Sea Hawks, INAS 310 "Cobras" with Breguet Alizé and INAS 321 with Alouette III helicopters, also planned to strike Barisal, Chittagong and Cox's Bazar after the start of hostilities.

PAF preparations to counter IAF over East Pakistan

[edit]Pakistan high command was fully aware that the IAF considerably outnumbered the PAF eastern detachment (161 serviceable aircraft to 16 aircraft in December 1971),[69] and that the IAF also held the qualitative edge in aircraft and technology. Pakistani planners had assumed the PAF will be neutralized within 24 hours of IAF launching combat operations over East Pakistan.[70] There was only one fully functional, extended combat-capable airbase (at Tejgaon near Dhaka) in all of East Pakistan, as the satellite air bases at Chittagong, Comilla, Jessore, Barisal, Ishwardi, Lalmonirhat Airport, Cox's Bazar and Shamshernagar lacked the service facilities for sustaining prolonged air operations. The PAF had plans to deploy a squadron of Shenyang F-6 planes at Kurmitola (now Shahjalal International Airport) in 1971. These planes were temporarily deployed but ultimately withdrawn because, although the runway was functional at that base, the base was not fully functional enough to support the planes, and the lack of infrastructure meant PAF could not deploy any additional planes.[71] This marginalization and neglect of East Pakistani defenses since 1948 had hamstrung the PAF Eastern contingent in 1971, when its capabilities were put to the test.

Pakistan deployed no additional air defense assets other than one light antiaircraft "Ack-Ack" regiment and a few additional batteries to assist the PAF in 1971. The 6th Light Ack-Ack guarded Dhaka,[70] the 46th Light Ack-Ack battery was in Chittagong,[72] and elements of the 43rd Ack-Ack were present in areas around East Pakistan. The caliber of the regiment was not enhanced to heavy, and no surface-to-air missiles (SAMs) were deployed in East Pakistan. The only long-range radar, a Russian P-35, was also taken to West Pakistan, along with all the C-130 Hercules transport planes.[53] Several dummies were deployed at the airbases to deceive the IAF, however. To augment short range radar cover from the Plessey AR-1 (Operated by No. 4017 Radar Squadron),[73] 246 Mobile Observer Unit was deployed around the country. These men were exposed to Mukti Bahini attacks, however, which reduced their effectiveness and they were ultimately withdrawn to Dhaka.[15]

The undeclared war: November 1971

[edit]After August 1971, the Mukti Bahini began to launch conventional attacks along the border areas, while groups of guerrillas and naval commandos stepped up their activities. By the end of November, Pakistani Forces had lost control of 5,000 square kilometres (1,900 sq mi) of territories to the Mukti Bahini. PAF flew 100 sorties in support of the ground forces between October and 3 December. These included the bombing of Belonia on 7 and 10 November, before the Mukti Bahini captured the area;[74][75] several ground attack sorties near Garibpur between 19 and 22 November, leading to the aerial Battle of Boyra on 22 November; and attacks on Indian troops near Akhuara on 2 December 1971.[76][77] Pakistan had lost 2 planes on 22 November over Boyra, and as no replacement aircraft had been sent from West Pakistan, were down to 14 operational jets by December 1971.

War begins: first air strike in Bangladesh

[edit]Pakistan Air Force launched Operation Chengis Khan against several Indian Air Force bases in the west in the evening of 3 December 1971. Following this the preemptive strike by the PAF on its airfields in the western sector, the IAF went into action at midnight on 3 December 1971 with the goal of knocking the PAF Sabres out of action. The Western air campaign was, at least in the initial days, limited to striking PAF forward bases and providing ground support, and was not aimed at achieving air supremacy.[78] Kilo Flight Otter and the helicopter took off from their respective bases after 9:30 PM and hit the oil depots at Naryanganj and Chittagong,[79] which the Mukti Bahini guerrillas had been unable to sabotage due to tight security.[80] After the Kilo flight strike, IAF commenced combat operations in East Pakistan. IAF station Commanders had met at Shillong on 3 December to finalize operational plans while IAF squadrons moved to forward bases, now sprang into action.

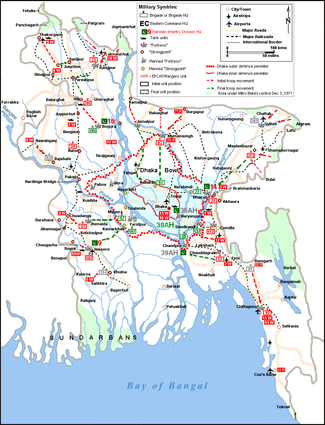

4 December

[edit]Canberra bombers struck Tejgaon repeatedly in the early hours of 4 December. The PAF No. 14 operated only Sabres, which lacked night fighting capability, so the bombers were opposed only by the guns of the Pakistani light ack-ack regiment. IAF Hunters attacked Chittagong in the morning and Narayangunj fuel depots in the afternoon. Pakistani sources claim IAF lost two Canberras over Chittagong.[79] Tejgaon was repeatedly attacked by Hunters of the No. 7, and Squadrons No. 14, No. 17, and No. 37, Su-7s (No. 221 Squadron), and MiG-21s (No. 28 Squadron) on throughout the day. PAF was on full alert and Sabres flew Combat Air Patrols, resulting in several dogfights with Indian jets. The first daytime raids were flown by Hunters of No. 17 Squadron, and these were given top cover by four MiG-21s from No.28 Squadron. No. 14 Squadron also struck Kurmitola AFB, hitting the hangars and other installations with rockets. MiGs from 28 Squadron struck Tejgaon in the afternoon, destroying a Twin otter on the ground.

PAF lost two Sabres in dog fights over Dhaka - to IAF Hunters striking Tejgaon. Wing Commander S. M. Ahmed and Flight Lt. Saeed ejected safely over East Pakistan, but were not seen again. They were assumed killed by a hostile local populace.[81] Wing Commander Nadrinder Chatrath of No 17 Squadron and Flight Officer Harish Masand each are credited with a Sabre kill. Squadron Leader K.D. Mehra of IAF No. 14 squadron was shot down by a Sabre.[82] Later in the day PAF Flight officer Sajjad Noor was shot down by IAF NO 14 Squadron Leader Sundaresan, who lost his wingman when PAF Squadron Leader Dilawar Hussain shot down the Hunter of Flight Lt K. C. Tremenhere during the same dogfight. Flight Lt. K. C. Tremenhere and Sajjad Noor ejected safely, and both were rescued and Tremenhere became a POW.[83]

PAF had flown thirty two operational sorties against IAF incursions on 4 December, expending 30,000 rounds of ammunition, while the ground-based weapons had fired 70,000 rounds on the same day, the highest expenditure per day per aircraft of ammunition in the history of the PAF. Pakistani authorities claimed between 10 and 12 IAF planes were destroyed, and took measures to conserve ammunition in anticipation of a long war.[79] IAF claimed five Sabres shot down and another three destroyed on the ground. India's only aircraft carrier INS Vikrant (with its Sea Hawk fighter bombers and Breguet Alize ASW aircraft) mounted attacks against the civilian airport at Cox's Bazar and Chittagong Harbor.

In addition to attacking Tezgaon, Chattagong, Jessore and Ishwardi airfields, IAF attacked several other targets, including the Teesta Bridge, Chandpur and Goalanda Ferry Ghats and flew several ground support missions. The IAF lost six Hunters (two in air combat) and one Su-7 shot down during the day. Two Hunters of No. 7 Squadron were shot down by ack ack fire while hitting an ammunition train at Lal Munir Hat, one pilot was KIA. One of the pilots of the stricken planes, Squadron Leader S. K. Gupta, safely ejected at Bagdogra.[84] Squadron Leader K. D. Mehra's Hunter was shot down by ack ack[84] he managed to evade capture and get back to Indian territory. Two Hunters of IAF No. 37 Squadron was shot down over Tezgaon and two pilots - Squadron Leader S. B. Samanta and Fg. Officer S. G. Khonde was killed.[84] One No. 221 Squadron l Su-7 was shot down with the pilot, Squadron Leader V. Bhutani taken POW.[84] The mission to knock PAF off the air had failed and no significant damage was done to the PAF assets in well-dispersed and camouflaged locations. While The PAF did not oppose all IAF incursions over Dhaka, choosing to fight when odds were even, it had forcing many IAF missions to abort. The PAF was not able to intercept any IAF missions outside Dhaka. IAF Eastern Command sent No. 30 squadron and other assets to the Western Front, realizing PAF posed little threat to IAF bases in the east.

5 December

[edit]Canberra bombers bombed Tejgaon and Kurmitola at night. The IAF switched tactics, ground support and attacks on Pakistani targets continued, including the first use of napalm in combat by IAF near Jessore, but having lost 5 aircraft over Dhaka, attacks on Tejgaon were scaled back. IAF Squadron No. 37, No. 17, No. 221 and No. 22 flew sorties towards Tejgaon to lure PAF Sabres into dog fights outside Dhaka without success. The lessening pressure led to the PAF flying some ground support missions over Comilla and other areas. In total 20 operational sorties were flown by the Sabres, and 12,000 rounds of ammunition were used up during 5 December by the PAF.[85] The United Nations had requested a ceasefire in the air campaign over Dhaka to take place between 10:30 AM and 12:30 PM, so a C-130 could evacuate foreign civilians from Dhaka, and both the Pakistan and Indian governments had agreed to the request.[86]

6 December: PAF grounded

[edit]Early in the morning of 6 December a sortie by four PAF Sabres intercepted four Hunters of IAF No. 17 squadron without any dogfights near Laksham. After the Sabres returned and landed at Tejgaon, and before the duty flight had taken off,[85] four MiG-21s from No. 28 and No. 4 Squadron, flying from Gauhati under the command of Wing Commander B. K. Bishnoi at very low level, escorted by another four Mig 21s, bombed Tejgaon airstrip with 500 kg. bombs, scoring several hits on the runway. Two craters, each ten meters wide, had rendered the runway unusable. The MiGs used steep glide instead of a dive to bomb Tejgaon. Hunters from No. 14 squadron then attacked Tejgaon with napalm, causing little damage.[87] Another mission bombed the Kurmitola runway.[88] MiG-21s also attacked Pakistani positions in Sylhet and Comilla, during which No. 28 squadron lost one plane.[89] Su-7s of No. 221 Squadron struck targets north of Jessore, Gnats of No. 15 Squadron and Hunters from No. 37 Squadron struck Hili, while Gnats of No. 22 Squadron attacked Barisal airfield. MiG-21s and Hunters of No. 28 and No. 14 Squadrons struck Tejgaon repeatedly, one raid occurred during the cease fire brokered by the UN and foiled the attempt to evacuate foreign civilians from Dhaka.[90]

Pakistan Air force and army engineers estimated that it would need 8 hours of continuous effort to repair the runway. An engineering platoon, helped by loyal civilians, worked uninterrupted during the night of 6 December, and by dawn on 7 December, three bomb craters were filled up and the runway was ready for flying operations.[70][91] The IAF had launched no night raids in East Pakistan on 6 December. Pakistan Army 314th brigade (CO: Col. Fazle Hamid) used road and river transports to retreat to Dhaka at night due to the daytime dominance of IAF.[70]

7 December

[edit]PAF pilots were waiting for the dawn to get their Sabres airborne, when a single Mig-21 bombed and cratered the Tejgaon runway again. Kurmitola was to remain operational until the morning of 7 December, when Mig-21s of No. 28 Squadron again hit that runway. IAF squadrons repeatedly attacked Tejgaon, and No. 14 Squadron attacked Barisal airfield. With the Sabres grounded, IAF No. 7 Squadron was pulled out of the eastern operations on 6 December to help the army in the west. A Hunter from No. 14 Squadron was shot down by anti-aircraft fire during the day. INS Vikrant, the Navy's sole aircraft carrier at the time, sent Sea Hawks to bomb Chittagong harbor, Cox's Bazar, and Barisal. PAF engineers now estimated that 36 hours of work without further damage was needed to make Tejgaon AFB operational again. The IAF attacked Tejgaon repeatedly for the duration of the war to prevent any required repairs to the runway. In desperation, it was suggested that the broad streets at second capital be used as runways, but technical problems ruled out that possibility, effectively grounding the PAF Sabres in East Pakistan for the duration.[70]

Pakistan air operations until 16 December 1971

[edit]6th Light Ack-Ack regiment (CO: Lt. Col. Muhammad Afzal) became the only defense of Tejgaon AFB after the runway was cratered on 7 December. Daily IAF bombing raids kept the Pakistan forces from making the necessary repairs for the remainder of the war.[70] Four Caribous from IAF No. 33 Squadron bombed Tejgaon on the early hours of 8 December followed by MiG-21s.[92] However, PAF and Army aviation helicopters continued flying daily night missions to Pakistan Army positions at Bogra, Comilla, Moulvibazar, Khulna and other bases carrying reinforcements, supplies, munitions and evacuating the wounded.[citation needed] Air Commodore Inamul Haque Khan concluded that Tejgaon would remain inoperable due to IAF bombing for the rest of the war, so he decided to evacuate the Sabre pilots. PAF had considered using the wide roads adjacent to the Airport to operate the Sabres but they were not carried out. One Twin Otter carrying nine Sabre pilots flew to Burma on 8 December, and the remaining pilots were flown out of Dhaka on 10 December in a Plant Protection Agency Beaver aircraft.[93][70] Army aviation Squadron No. 4, commanded by Lt. Col Liakat Bokhari (assumed command after October 1971), lost one Mi -8 helicopter on 4 Dec to IAF Bombing and another MI-8 crashed on 10 December while taking off. Gen Niazi had considered using the Helicopters to bomb the Indian army troops at night, but it was not implemented.

Kilo Flight missions

[edit]After their initial mission, Kilo Flight moved from Kailashahar to Agartala to cut down fuel usage and turn around time after 4 December 1971, and used Shamshernagar as a forward base.[94] The Otter flew 12 and the Alouette 77 sorties between 4 and 16 December 1971,[95] about 40 of them were combat missions to attack ground targets in Sylhet, Comilla, Daudkandi and Narshingdi.[96] The Otter flew several sorties and hit Pakistani positions in Syhlet on 5 December and again on 6 December, while the helicopter flew four sorties and rocketed Pakistani troops in Sylhet, Maulivibazar and on the River Kushiyara on the same day.[97]

Indian troops made a heliborne infantry assault by two companies in about nine Mil Mi-4s, escorted by "gunship" Alouttes on 7 December near Sylhet.[98] The Kilo Flight Alouette provided fire support during the landing, then rocked and strafed targets near the Sylhet Circuit house and on Pakistani positions along the river Surma to contain the Pakistani response.[99] Flight Lt. Singla won the Vir Chakra and Flight Lt. Sultan Mahmud was awarded the Bir Uttam medals for this operation.[100] The helicopter attacked Pakistani troops retreating from Sylhet to Bhairab on 8 December while the Otter attacked Pakistani troops crossing the Kushiyara river on 7 and 8 December several times, sinking two barges. Captain Shahabuddinn Ahmed in the Alouette flew an unsuccessful sortie[97][96] to rescue Squadron Leader R.C Sachdeva, who had bailed out near Naryanganj on 10 December.[101]

IAF Activity until 16 December 1971

[edit]

IAF focus shifted on supporting the Mitro Bahini advance following the grounding of PAF after 7 December 1971. Gnat squadrons, previously employed in flying combat air patrols over IAF bases, now began attacking targets inside Pakistani territory along other IAF squadrons. The IAF flew interdiction missions for the remainder of the war, shooting up ammunition dumps and other fixed installations. Gnats and Sukhoi Su-7s flew many missions in support of army units as they moved swiftly towards Dhaka, delivering ordnance (such as iron bombs) to take out enemy bunkers which occasionally posed an obstacle to the advancing infantry. Canberras repeatedly struck Jessore, forcing the enemy to abandon this strategic city. The IAF also bombed other airfields, including the abandoned World War II airfields of Comilla, Lal Munir Hat, and Shamsher Nagar throughout the war, denying their use to PAF planes that may be moved by road, as well as to any external aerial reinforcement. INS Vikrant, the Navy's sole aircraft carrier, periodically sent Sea Hawks to bomb the Chittagong harbor and airport throughout the war, while also sent bombing missions to Cox's Bazar, Barisal, Khulna and Mongla ports, and to Chandpur and other Pakistani positions between 7–14 December 1971.

Anti-shipping missions struck ships and ferries, while ferry ghats, bridges, army positions, troop convoys and ports were also bombed. Ferries across major river crossings were sunk by the IAF, thus denying the Pakistani army its line of retreat to Dhaka. Tejgaon was daily bombed to keep the PAF from repairing the runway[102] along with other airfields. On 10 December, IAF heli-lifted troops of the IV Corps from Ashuganj to Raipura and Narsingi in what came to be termed Operation Cactus-Lilly (also known as the Helibridge over Meghna). Four infantry battalions and several light PT-76 tanks crossed the River Meghna, after Pakistan Army had blown up the Bhairab Bridge, allowing the Indian Army to continue their advance in the face of stiff resistance at the Ashuganj.[103][104] Kilo flight crafts were part of the air cover, attacking Pakistani positions near Narshigndi, while Mukti Bahini organized about 300 local boats to ferry soldiers, cannons and munitions to augment the heli-borne operation.[105][106] 10 and 11 December Su-7 dropped napalm on Bhairab twice.[107] Three converted An-12s struck the Jaydebpur Ordnance Factory in East Pakistan on 13 December.[108]

Tangail para drop

[edit]The Tangail airdrop on 11 December involved several An-12s, C-119s, 2 Caribous and Dakotas from various squadrons airdroping 700 troops of the 2nd para battalion near Tangail about 15 km north of Dhaka. Gnats from No. 22 Squadron provided top cover for the operation. The troops linked up with various Mukti Bahini and Indian Army formations from 101 Communication Zone advancing from the North and then pushed south towards Dhaka, while the IV Corps formations that had crossed over the Meghna converged on Dhaka from the North and East.

MiGs attack Governor House

[edit]On the morning of 14 December, a message was intercepted by Indian Intelligence concerning a high-level meeting of the civilian administration in East Pakistan. A decision was then made to mount an attack. Within 15 minutes of the interception of the message, a strike was launched against Dhaka. Armed with tourist guide maps of the city, four MiG-21s of No. 28 Squadron became airborne. Only a few minutes had passed after the meeting had started when the IAF aircraft blasted the Governors House with 57 mm. rockets, ripping the massive roof off the main hall and turning the building into a smoldering wreck. The Governor of East Pakistan, Mr. A. M. Malik, was so shocked after the incident that he resigned on the spot by writing his resignation on a piece of paper, thereby renouncing all ties with the West Pakistani administration. He then took refuge at the InterContinental Hotel in Dhaka under UN flag.

Fate of the Pakistani Navy in East Pakistan

[edit]

Pakistan Forces General Headquarters had declined to provide a substantial naval contingent for the defense of East Pakistan, for two reasons. First, they had an inadequate number of ships to challenge the Indian navy on both fronts. Second, the PAF in the east was not deemed strong enough to protect the ships from Indian airpower (i.e. both the IAF and the Indian Navy Air Arm). Pakistan Eastern Command had planned to fight the war without the Navy, and faced with a hopeless task against overwhelming odds, the Navy planned to remain in port when war broke out.[109] The fate of Pakistani naval vessels in December was ample proof of the soundness of this decision, and the repercussions of neglecting East Pakistan defense infrastructure, which was the reason the PAF could only station 1 squadron of planes there.[71] The Pakistan Navy had 4 Gunboats (PNS Jessore, PNS Rajshahi, PNS Comilla, and PNS Sylhet). All were 345 ton vessels, capable of attaining a maximum speed of 20 knots, crewed by 29 sailors, and fitted with 40/60 mm. cannons and machine guns, in East Pakistan. One patrol boat (PNS Balaghat) and 17 armed boats (armed with 12.7mm./20mm. guns and/or .50 or .303 Browning machine guns), in addition to numerous civilian-owned boats requisitioned and armed with various weapons by Pakistani forces, were also part of the Pakistani naval contingent.[110] The improvised armed boats were adequate for patrolling and anti-insurgency operations, but hopelessly out of place in conventional warfare. Before the start of hostilities in December, PNS Jessore was in Khulna with 4 other boats, PNS Rajshahi, PNS Comilla, and PNS Balaghat were at Chittagong, and PNS Sylhet was undergoing repairs at a dry-dock near Dhaka. The outbreak of hostilities on 3 December found most of these boats scattered around the province.[79]

Indian aircraft attacked the Rajshahi and Comilla near Chittagong on 4 December, with the Rajshahi damaged and the Comilla sunk.[109] The Balaghat, which was not attacked, rescued the Comilla crew and returned to Chittagong with the surviving ships. On 5 December, Indian planes sank two patrol boats in Khulna. The PNS Sylhet was destroyed on 6 December and the Balaghat on 9 December by Indian aircraft.

The 39th Division (under General Rahim Khan) Headquarters at Chandpur had requested evacuation by river on 8 December. Under the escort of a gunboat, the flotilla, made up of local launches, sailed in the early hours of 10 December. The IAF spotted and bombed the ships, and PNS Jessore, which had withdrawn from Khulna to Dacca, was destroyed escorting boats evacuating Pakistani troops from Chandpur while other boats were either sunk or beached themselves and failed to reach Dhaka.[111] The survivors later were evacuated by ships and helicopters operating at night. PNS Rajshahi was repaired, and under the command of Lt. Commander Sikander Hayat, managed to evade the Indian blockade and reach Malaysia before the surrender on 16 December. From there, it sailed to Karachi and continued to serve in the Pakistan navy.

Blue on blue: Tragedy near Khulna

[edit]Indian Army Eastern Command had ordered Bangladesh Navy gunboats BNS Palash and BNS Padma, accompanied by INS Panvel (CO: Lt. Commander J. P. A. Noronha, Indian Navy) and under the overall command of Commander M. N. Samant of Indian Navy, to sail to the port at Mongla in an anti-shipping mission.[112][113] The Bangladesh Navy ships flew the national ensign, carried Bengali seamen and Indian command crews, and, under the advice of Indian Eastern Air command, had painted their superstructure yellow to avoid misidentification and fixed 15 feet by 10 feet yellow cloths on their bridges to identify them as friendly crafts to the IAF. This had been reported back to Eastern Air Command.[114] This task force ("Alpha Force"), accompanied by BST craft Chitrangada sailed from Hasnabad on 6 December, entered Mangla at 7:30 AM on 10 December, and took over the abandoned port facility. Commander Samant then decided to sail towards Khulna, which was 20 miles east of Dum Dum airport, lay north of the bomb line and a designated target of IAF planes. This was not part of the mission but Commander Samant decided to push on anyway, leaving Chitrangada at Mongla.

The flotilla sailed along the Passur river was closing on Khulna dockyard by 11:45 AM, Panvel in the lead, followed by and Palash when three Gnats dived on them. Commander Samant on INS Panvel recognized the IAF planes and ordered all the ships to hold fire. The Gnats hit BNS Padma with rockets, which caught fire and sank. Palash was hit next, her captain refused to open fire on the Gnats and beached the ship, where it was again attacked. Bengali Engine Room artificer Muhammad Ruhul Amin was critically wounded, while trying to keep the ship operational although others were abandoning the ship. Panvel opened up on the IAF planes, then beached on the riverbank and made smoke to appear critically damaged. After the IAF planes departed, Panvel rescued some of the survivors and returned to Indian territory. The incident cost the lives of three Bengali naval commandos and 7 Bengali sailors including Muhibullah Bir Bikram, while 6 naval commandos, 1 BSF JCO, 3 Indian officers, and 7 Bengali seamen were injured. Twenty one Indian and Bengali sailors became POWs.[115]

The Indian Navy gave 13 awards (including 3 Mahavir Chakras and 5 Vir Chakras) to the Indian rank-and-file involved in this incident.[116] Bengali Seaman Ruhul Amin, who tried to save BNS Palash despite being wounded and ordered to abandon ship, and who later died under torture after being taken captive, was awarded the Bir Shreshtro medal by the Bangladeshi Government.

Aftermath

[edit]Pakistani authorities claimed that between 4–15 December the IAF lost 22 to 24 aircraft (7 to the PAF and the rest to ack-ack units).[70] The IAF records 19 aircraft lost in East Pakistan, 3 in air combat, 6 to accidents and the rest to ack-ack, while 5 Sabres were shot down by IAF planes.[89] Pakistan Armed Forces Headquarters had issued orders to blow up all remaining the aircraft, but Air Commodore Inamul Haque Khan had pointed out that the sight of burning planes would demoralize the Pa kistani troops defending Dacca.[117] Therefore, PAF personnel destroyed the ammunition stocks and sabotaged the electric and hydraulic systems of the aircraft on 15 December.

Tejgaon airport was made operational by 25 December 1971, through the joint efforts of Indian and Pakistani airmen and engineers and Bengali workers. Kilo flight relocated to Tezgaon during that period. The newly formed Bangladesh Air Force lacked trained personnel and for some time the base was administered by IAF Air Commodore Kingly.[citation needed] The government of Bangladesh awarded six Bir Uttom medals (Flight Lieutenant Sultan Mahmud, Shamsul Alam, Badrul Alam, Captain Akram Ahmed, Shahabuddin Ahmed and Sharafuddin) and six Bir Protik medals (Captains A.S.M.A Khaleque, Kazi Abdus Satter and Abdul Mukeet, Sergeant Shahidullah, Corporal Muzammel Haque and LAC Rustom Ali) to Kilo Flight Personnel.[118] IAF awarded Vir Chakra to Squadron Leader Sanjay Kumar Chowdhury and FL Chandra Mohan Singla for their service in Kilo Flight.[101]

Pakistan Air Force reconstituted No. 14 Squadron in 1972, which was assigned to fly F-6 fighters. PAF awarded Hilal-e-Jurat to Air Commodore Inamul Haque Khan, PAF commander in East Pakistan. No. 14 Squadron pilots were given five Sitara-e-Jurat medals. Wing Commander Syed M. Ahmed, who was missing after his Sabre was shot down, Lt. Col Syed Liakat Bhukhari (CO No. 4 Army Aviation Squadron) and Flight Lieutenant S. Safi Ahmed (CO 246 MOU Squadron – killed in Mymensingh on 28 March 1971) were also awarded the Sitara-e-Jurat. Indian Government awarded 3 Maha Vir Chakra, 26 Vir Chakra and 17 Vayu Sena medals to IAF personnel for the Bangladesh Liberation War campaign.

Kilo Flight becomes Bangladesh Air Force

[edit]

Under the leadership of Air Commodore A. K. Khandker, the newly formed Bangladesh Air Force began to organize itself. The DC-3 was given to Bangladesh Biman, but it crashed during a test flight, claiming the life of Kilo flight members Captain Khaleque and Sharafuddin.[119] Former PAF personnel and officers were requested to muster in Dhaka over radio and the personnel were grouped into three squadrons under one operational wing under Squadron Leader Manjoor. Squadron Leader Sultan Mahmud commanded Squadron no 501, Squadron Leader Sadruddin Squadron no 507 and Wahidur Rahman commended the third squadron.[97]

Pakistani forces had abandoned eleven Canadair F-86 Sabre jets, two T-33 Shooting Stars, one Alouette III and one Hiller UH-12E4 helicopter in Dhaka.[120][121] Eight Sabres were made operational later by Bengali technicians by March 1972.[122]

The Hiller was taken over by Bangladesh Army, while Bengali airmen set to work on fixing the aircraft. By March 1972, eight Sabers,[122] one T-33 and the Alouette was airworthy. Five Sabers, the lone T-33 and the Alouette were activated for service. On 26 March 1972, to mark the first anniversary of Independence day, Bangladesh Air Force staged a fly past with two F-86 Sabres, one T-33, three Alouettes and one DHC-3 Otter.[123][124] These aircraft remained operational until replaced by more modern aircraft after 1973.

Importance of air power during Bangladesh Liberation War

[edit]After the beginning of Operation Searchlight, PAF jets flew sorties against Mukti Bahini positions to aid the Pakistan Army, and helicopters ferried reinforcements and supplies to remote Army bases surrounded by Mukti Bahini, evacuated wounded from isolated bases, acted as artillery spotters, flew reconnaissance missions over hostile territory, and air-dropped combat troops off in remote places to outflank and cutoff Mukti Bahini positions.[80] This proved critical to the initial survival and ultimate success of the Pakistani troops during the early phases of the operation.[125][28]

Deciding factors of the East Pakistan defense plan

[edit]

The Pakistan army 1971 military strategy depended on winning an overwhelming, decisive victory over Indian forces in the Western Front, while the contingent in occupied Bangladesh needed only to hold out until the issue was decided in the West.[126][127][128] Eastern Command devised four strategic concepts for the defense of East Pakistan, and when the final course of action was adopted, Mukti Bahini achievements and the assumed IAF dominance of the skies influenced their decision. The strategic plans were:[126]

- Deploying all available forces to defend the Dhaka Bowl along the Meghna, Jamuna and Padma Rivers. The Pakistan Army could use interior lines to switch forces as needed, and build up a strategic reserve while fighting on a narrower front. The disadvantage was that large tracts of areas outside the bowl would be lost without much effort from the invaders; India could set up the Bangladesh Government easily inside the province. Also, it gave the Indians the opportunity to divert some of their forces to the west (thus threatening the balance of forces there) where a near-parity in forces was needed for a decisive result.

- Fortress Deployment: Fortify and provision certain cities along expected Indian lines of advance, deploy troops along the border, then make a fighting withdrawal to the fortresses and hold out until Pakistan achieved victory in the west. This meant surrendering the initiative to the enemy, and being cutoff without mutual support, giving the Indians the choice to bypass and contain some fortresses and concentrate on others. This concept had two advantages: it did not call for the voluntary surrender of territory, concentrated forces and required limited mobility. Also, there was a chance the fortresses might tie up a large number of Indian forces and they might not have sufficient forces to threaten the Dhaka Bowl, if they bypassed the fortresses.

The other two options called for a more flexible, mobile defense of the province.

- Deploy troops in depth near the border then conduct a fighting withdrawal towards the Dhaka Bowl, and hold out until a decision is reached in the Western Front.

- Positional Defense: Use mobility to parry initial Indian thrusts then redeploy forces to take advantage of any opportunity for counterattack or fall back to defensive position. This was considered the best option given the geographic feature of Bangladesh. Also, a large uncommitted reserve force was needed to execute this strategy properly; the Eastern Command had no such reserves, and could not create one unless reinforced by West Pakistan or by abandoning the "defending every inch of the province" concept.

However, Pakistan Command did not adopt the flexible defense strategy because of the following factors:

- Nearly all roads led to Dhaka, there were few lateral roads. Wide rivers and, during the April–October monsoon, 300 other water channels were a formidable challenge to the movement of troops and supplies. Air and river control were necessary for unhindered movement along interior lines.[129] General Niazi had ordered the Pakistan army to live off the land because of logistical difficulties,[130] and Maj. General A.O. Mittha (Quartermaster General, Pakistan Army) had recommended setting up river-transport battalions, cargo and tanker flotillas and increasing the number of helicopters in the province (none of which happened). Instead, the C-130 planes (which had played a crucial role during Operation Searchlight) were withdrawn from the province,[citation needed] diminishing the airlift capacity of the Pakistani forces further. The Mukti Bahini had sabotaged 231 bridges and 122 rail lines[131] by November 1971 (thus diminishing transport capacity to 10 percent of normal), and complicated the delivery of the daily minimum 600 tons of supplies to the army units.[132] Mukti Bahini Naval commandos had managed to sink or damage 126 ships/coasters/ferries during that same time span, while one source confirms at least 65 vessels of various types (15 Pakistani ships, 11 coasters, 7 gunboats, 11 barges, 2 tankers and 19 river craft by November 1971).[133] had been sunk between August–November 1971. At least 100,000 tons of shipping was sunk or crippled, jetties and wharves were disabled and channels blocked, and the commandos kept East Pakistan in a state of siege without having a single vessel[134] The operational capability of Pakistan Navy was reduced as a result of Operation Jackpot.

Mobility of Pakistan Forces were hampered due to the above factors, and they also feared being ambushed by the Bangladesh Forces, if they moved at night. Pakistani planners expected the PAF to last 24 hours in the east, so IAF dominance would pose considerable threat to Pakistan troop convoys and can unhinge any strategy depended on mobility. The fortress concept was adopted; the planners decided on a single defensive deployment of troops on the border, which went against the troop deployments advocated by earlier plans. This was done to stick to the GHQ order of not surrendering any territory to the Mukti Bahini. When devising troop deployments, the planners mixed political considerations with strategic ones and envisioned a forward-leaning defence in depth:[135][136][137][138]

The short, but intense engagements between the Indian forces allied to Mukti Bahini and the Pakistani Army lasted only 14 days, between 3 and 16 December 1971. The near-total domination by the Indian forces and the Mukti Bahini was due to two major reasons: the first, and likely the most important, was the fact that the Bengali Population and the Awami League-led resistance had already heavily weakened Pakistani Forces, through a guerrilla campaign where the Bangladesh Forces emerged victorious . The second major reason was the total air supremacy, that the IAF gained in the opening days of the war and the excellent co-ordination between the Indian Army, Air Force, Navy, and the Mukti Bahini. Guided by the Mukti Bahini, Indian troops chose to take alternative routes, by passing some Pakistani strong points and blocking others, while concentrating superior forces where it was needed, augmented by their superiority in Artillery and Airpower. Pakistan Army were forced to fight local actions, prevented from coordinating their actions on a large scale,[128][139] and the planned redeployment of Pakistan forces for the defense of Dhaka could not take place because of fear of Mukti Bahini ambush at night and action of the IAF during the day.[140][141]

Notes

[edit]- ^ "1971 war: How IAF's air superiority helped in the early fall of Dhaka". Firstpost. 13 December 2021.

- ^ "Operation Kilo Flight: A story of valour". The Daily Star. 23 August 2021.

- ^ a b [1] Archived 9 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine IAF 1971 Losses

- ^ "TRAUMA AND RECONSTRUCTION (1971-1980)". Pakistan Air Force Official Website. Archived from the original on 26 August 2022. Retrieved 25 September 2022.

- ^ "Firestorm from the Air". The Daily Star. 16 December 2014.

- ^ United Press International. "Indian planes Bomb Dacca Orphanage, hundreds die". The Bryan Times. Retrieved 23 April 2023.

- ^ a b c Sher Khan. "Last Flight from East Pakistan". Defence Journal. Archived from the original on 15 April 2001.

- ^ Nasir Uddin, Juddhey Juddhey Swadhinata, pp 47

- ^ Mohan & Chopra 2013, pp. 32–33

- ^ * [2]

- ^ Gp Capt NA Moitra VM

- ^ * [3] Archived 17 January 2013 at archive.today

- ^ "IAF Claims vs. Official List of PAF Losses". Bharat-rakshak.com. Archived from the original on 26 February 2012. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- ^ * [4] Archived 17 January 2013 at archive.today

- ^ a b Mohan & Chopra 2013, pp. 50–51

- ^ a b c Bhuiyan, Kamrul Hassan, Shadinata Volume one, pp.129,130

- ^ Mohan & Chopra 2013, pp. 33, 35

- ^ Khandker, A.K, 1971: Bhetore Baire p52

- ^ Salik 1997, p. 40

- ^ Salik 1997, p. 45

- ^ Bhuiyan, Kamrul Hassan, Shadinata Volume one, pp128

- ^ Salik 1997, pp. 87, 90

- ^ a b c Salik 1997, p. 90

- ^ Bhuiyan, Kamrul Hassan, Shadinata Volume one, p126

- ^ a b Mohan & Chopra 2013, p. 34

- ^ a b c Kabira, Sahariyara (1992). Sekṭara kamānḍārara balachena muktiyuddhera smaraṇīẏa ghaṭanā. Dhaka: Māolā Brādārsa. p. 96. ISBN 984-410-002-X.

- ^ Salik 1997, pp. 81–82

- ^ a b Salik 1997, p. 82

- ^ Salik 1997, p. 84

- ^ Islam 2006, p. 163

- ^ Salik 1997, pp. 80–81

- ^ a b c Islam 2006, p. 121

- ^ a b c Mohan & Chopra 2013, p. 51

- ^ Islam, Rafiqul, Muktijuddher Itihas, p185

- ^ Islam, Rafiqul, Muktijuddher Itihas, pp185

- ^ Chowdhury, Abu Osman, Our Struggle is The Struggle for Independence, pp159

- ^ Chowdhury, Abu Osman, Our Struggle is The Struggle for Independence, pp97

- ^ Islam, Rafiqul, Muktijuddher Itihas, pp. 177–178

- ^ Islam, Rafiqul, Muktijuddher Itihas, p202

- ^ Nasir Uddin, Juddhey Juddhey Swadhinata, pp120, pp124

- ^ Islam 2006, p. 213

- ^ Islam 2006, p. 216

- ^ Islam, Rafiqul, Muktijuddher Itihas, pp. 215

- ^ Islam, Rafiqul, Muktijuddher Itihas, pp. 140

- ^ Islam, Rafiqul, Muktijuddher Itihas, pp. 206

- ^ Safiullah 1989, p. 107

- ^ Islam 2006, p. 214

- ^ Islam, Rafiqul, Muktijuddher Itihas, pp. 224

- ^ Islam 2006, p. 240

- ^ Islam, Rafiqul, Muktijuddher Itihas, pp. 244

- ^ a b Islam 2006, p. 273

- ^ Safiullah 1989, pp. 136–137

- ^ a b * [5]

- ^ Nasir Uddin, Juddhey Juddhey Swadhinata, pp183

- ^ Uddin, Nasir, Juddhey Juddhey Swadhinata, ISBN 984-401-455-7, pp247

- ^ Khandker, A.K, 1971 Bhetore Baire p176, ISBN 978-984-90747-4-8

- ^ Mohan & Chopra 2013, p. 49

- ^ Khandker, A.K, 1971 Bhetore Baire p180, ISBN 978-984-90747-4-8

- ^ Khandker, A.K, 1971 Bhetore Baire p181, ISBN 978-984-90747-4-8

- ^ Mohan & Chopra 2013, pp. 95, 106–107

- ^ Mohan & Chopra 2013, pp. 57–58

- ^ Jacob 2004, p. 51

- ^ Mohan & Chopra 2013, p. 400

- ^ Mohan & Chopra 2013, pp. 61–62

- ^ a b "India - Pakistan War, 1971; Introduction". Acig.org. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- ^ Khandker, A.K, 1971 Bhetore Baire p83, ISBN 978-984-90747-4-8

- ^ Mohan & Chopra 2013, pp. 62, 108

- ^ Mohan & Chopra 2013, pp. 151, 157

- ^ Mohan & Chopra 2013, p. 379

- ^ a b c d e f g h Salik 1997, p. 132

- ^ a b Salik 1997, p. 123

- ^ Jacob 2004, p. 188

- ^ Mohan & Chopra 2013, pp. 62, 379

- ^ Safiullah 1989, p. 189

- ^ Islam, Rafiqul (1981) [First published 1974]. A Tale of Millions: Bangladesh Liberation War, 1971 (2nd ed.). Dacca: Bangladesh Books International. p. 392. OCLC 10495870.

- ^ Mohan & Chopra 2013, pp. 81, 88, 96

- ^ Nasir Uddin, Juddhey Juddhey Swadhinata, pp250

- ^ "Roar to victory: December 3, 1971". Dhaka Tribune. 3 December 2023.

- ^ a b c d Salik 1997, p. 134

- ^ a b Islam 2006, pp. 122, 213

- ^ Mohan & Chopra 2013, pp. 113, 119, 154

- ^ Mohan & Chopra 2013, pp. 115, 118, 130

- ^ Mohan & Chopra 2013, pp. 148–149

- ^ a b c d "Indian Air Force losses in the 1971 War". bharat-rakshak.com. Archived from the original on 21 July 2006. Retrieved 23 August 2006.

- ^ a b Salik 1997, p. 131

- ^ Mohan & Chopra 2013, pp. 187–188

- ^ Mohan & Chopra 2013, pp. 185, 189, 191–192

- ^ Mohan & Chopra 2013, p. 197

- ^ a b [6] Archived 9 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine IAF Losses in the East

- ^ Mohan & Chopra 2013, pp. 195, 199–200, 203

- ^ Mohan & Chopra 2013, p. 204

- ^ Mohan & Chopra 2013, pp. 229, 232–235

- ^ Mohan & Chopra 2013, pp. 263, 301

- ^ Nasir Uddin, Judhay Judjay Shadhinota, p. 120

- ^ Mohan & Chopra 2013, p. 383

- ^ a b Khandker, A.K, 1971 Bhetore Baire p186, ISBN 978-984-90747-4-8

- ^ a b c Islam, Rafikul, Sammukh samare Bangalee p574, OCLC 62916393

- ^ The Encyclopedia of 20th Century Air Warfare Edited by Chris Bishop (Amber Publishing 1997, republished 2004, pages 384–387 ISBN 1-904687-26-1)

- ^ Salik 1997, p. 169

- ^ Mohan & Chopra 2013, p. 226 Note 31

- ^ a b Mohan & Chopra 2013, p. 270

- ^ Salik 1997, p. 195

- ^ Islam 2006, p. 461

- ^ Nasir Uddin, Juddhey Juddhey Swadhinata, pp278

- ^ Rahman, Matiur, SommukhJuddho 1971, pp189, ISBN 978-984-91202-1-6

- ^ Nasir Uddin, Juddhey Juddhey Swadhinata, pp293

- ^ Nasir Uddin, Juddhey Juddhey Swadhinata, pp292, pp295

- ^ Mohan & Chopra 2013, p. 318

- ^ a b Salik 1997, p. 135

- ^ Salik 1997, p. 133

- ^ Salik 1997, pp. 175–176

- ^ Hiranandani, G. M. (2000). Transition to triumph: history of the Indian Navy, 1965-1975. New Delhi: Director Personnel Services (DPS). p. 154. ISBN 978-1-897829-72-1.

- ^ Mohan & Chopra 2013, p. 271

- ^ Jacob 2004, p. 92

- ^ Rahman, Md. Khalilur, Muktijuddhay Nou Obhijan, p234, ISBN 984-465-449-1

- ^ Rahman, Md. Khalilur, Muktijuddhay Nou Obhijan, p235, ISBN 984-465-449-1

- ^ "14 Squadron". globalsecurity.org.

- ^ Arefin, A.S.M Shamsul (1995). Muktiyuddhera prekshāpaṭe byaktira abasthāna [History, Standing of important persons involved in the Bangladesh War of Liberation]. University Press Limited. pp. 560–561, 583–585. ISBN 984-05-0146-1.

- ^ Accident description at the Aviation Safety Network

- ^ Mohan & Chopra 2013, p. 391

- ^ "IAF Claims vs. Official List of Pakistani Losses". Bharat-rakshak.com. Archived from the original on 1 May 2009. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- ^ a b "Bangladesh Air Force: Encyclopedia II - Bangladesh Air Force - History". Experiencefestival.com. Archived from the original on 17 July 2010. Retrieved 23 March 2010.

- ^ Islam, Rafikul, Sammukh samare Bangalee p575, OCLC 62916393

- ^ Mohan & Chopra 2013, p. 374

- ^ Qureshi 2006, pp. 55, 58

- ^ a b Salik 1997, p. 124

- ^ Islam 2006, p. 398

- ^ a b Nasir Uddin, Juddhey Juddhey Swadhinata, pp240- pp241

- ^ Khan 1992, pp. 111–112

- ^ Khan 1992, p. 90

- ^ Salik 1997, p. 104

- ^ Hassan, Moyeedul, Muldhara' 71, pp118 – pp119

- ^ Jacob 2004, p. 91

- ^ Roy 1995, pp. 141, 174

- ^ Salik 1997, pp. 123–126

- ^ Riza, Shaukat, Pakistan army 1966 – 1971, pp121- pp122

- ^ Matinuddin 1994, pp. 342–350

- ^ Khan 1973, pp. 107–112

- ^ Salik 1997, p. 194

- ^ Salik 1997, p. 196

- ^ Mohan & Chopra 2013, p. 264

References

[edit]- Islam, Rafiqul (2006) [First published 1974]. A Tale of Millions. Ananna. ISBN 984-412-033-0.

- Jacob, J. F. R. (2004) [First published 1997]. Surrender at Dacca: Birth of A Nation. The University Press Limited. ISBN 984-05-1532-2.

- Khan, Fazal Mukeem (1973). Pakistan's Crisis in Leadership. National Book Foundation. OCLC 976643179.

- Khan, Rao Farman Ali (1992). How Pakistan Got Divided. Lahore: Jang Publishers. OCLC 28547552.

- Matinuddin, Kamal (1994). Tragedy of Errors: East Pakistan Crisis 1968 – 1971. Lahore: Wajidalis. ISBN 978-969-8031-19-0.

- Mohan, P V S Jagan; Chopra, Samir (2013). Eagles over Bangladesh: The Indian Air Force in the 1971 Liberation War. Harper Collins India. ISBN 978-93-5136-163-3.

- Qureshi, Hakeem Arshad (2006). The Indo Pak War of 1971: A Soldiers Narrative. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-579778-7.

- Roy, Mihir K. (1995). War in the Indian Ocean. Lancer Publishers. ISBN 978-1-897829-11-0.

- Safiullah, K. M. (1989). Bangladesh at War. Academic Publishers. OCLC 24300969.

- Salik, Siddiq (1997) [First published 1977]. Witness to Surrender. Oxford University Press. ISBN 81-7062-108-9.