Sahlen Field

"The Jewel of Downtown Buffalo" "The House That Jimmy Built" | |

| |

Sahlen Field in 2023 | |

| |

| Former names | Pilot Field (1988–1995) Downtown Ballpark (1995) North AmeriCare Park (1995–1999) Dunn Tire Park (1999–2008) Coca-Cola Field (2009–2018) |

|---|---|

| Address | 1 James D. Griffin Plaza Buffalo, New York US |

| Coordinates | 42°52′52.7″N 78°52′27.4″W / 42.881306°N 78.874278°W |

| Elevation | 600 feet (180 m) |

| Public transit | |

| Owner | City of Buffalo |

| Operator | Bison Baseball, Inc. |

| Executive suites | 26 |

| Capacity | 16,600 (2019–present) 16,907 (2017–2018) 17,600 (2015–2016) 18,025 (2005–2014) 21,050 (1990–2004) 19,500 (1988–1989) |

| Record attendance | Baseball: 21,050 (June 3, 1990 / August 30, 2002) Concert: 27,000 (June 12, 2015) |

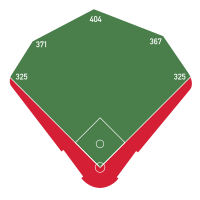

| Field size | Left field: 325 ft (99 m) Left-center field: 371 ft (113 m) Center field: 404 ft (123 m) Right-center field: 367 ft (112 m) Right field: 325 ft (99 m) Backstop: 55 ft (17 m)  |

| Acreage | 13 acres (5.3 ha) |

| Surface | Kentucky Bluegrass |

| Scoreboard | Daktronics LED |

| Construction | |

| Broke ground | July 10, 1986 |

| Opened | April 14, 1988 |

| Renovated | 2004, 2020, 2021 |

| Expanded | 1990 |

| Construction cost | US$42.4 million ($109 million in 2023 dollars[1]) |

| Architect | HOK Sport |

| Project manager | Ben B. Barnert |

| Structural engineer | Geiger Associates |

| General contractor | Cowper Construction Management |

| Tenants | |

| Buffalo Bisons (AA/IL/AAAE) 1988–present Buffalo Nighthawks (LPBL) 1998 Buffalo Bulls (NCAA) 2000 Empire State Yankees (IL) 2012 Toronto Blue Jays (MLB) 2020-2021 | |

| Website | |

| Sahlen Field | |

Sahlen Field is a baseball park in Buffalo, New York, United States. Originally known as Pilot Field, the venue has since been named Downtown Ballpark, North AmeriCare Park, Dunn Tire Park, and Coca-Cola Field. Home to the Buffalo Bisons of the International League, it opened on April 14, 1988, and can seat up to 16,600 people, making it the highest-capacity Triple-A ballpark in the United States. It replaced the Bisons' former home, War Memorial Stadium, where the team played from 1979 to 1987.

The stadium was the first retro-classic ballpark built in the world, and was designed with plans for Major League Baseball (MLB) expansion. Buffalo had not had an MLB team since the Buffalo Blues played for the Federal League in 1915. However, Bisons owner Robert E. Rich Jr. was unsuccessful in his efforts to bring an MLB franchise to the stadium between 1988 and 1995. The stadium was a temporary home to the Toronto Blue Jays of MLB in 2020 and 2021 when they were displaced by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Sahlen Field was previously home to the Buffalo Nighthawks of the Ladies Professional Baseball League in 1998, the Buffalo Bulls of the National Collegiate Athletic Association in 2000, and the Empire State Yankees of the International League in 2012. In addition to concerts and professional wrestling, the stadium has hosted major events including the National Old-Timers Baseball Classic (1988–1990), Triple-A All-Star Game (1988, 2012), StarGaze (1992–1993), World University Games (1993) and National Buffalo Wing Festival (2002–2019, 2025–present).

History

[edit]Professional baseball in Buffalo, 1877–1970

[edit]Buffalo began hosting professional baseball in 1877, when the Buffalo Bisons of the League Alliance began play at Riverside Park.[2] Over the next century, the city hosted major and minor league teams including the Buffalo Bisons (IA, 1878, 1887–1888), Buffalo Bisons (NL, 1879–1885), Buffalo Bisons (PL, 1890), and the Buffalo Blues (FL, 1914–1915).[2] The longest-tenured franchise was the minor league Buffalo Bisons, which was founded in 1886 and played exclusively in the International League starting in 1912.[2] This club played at Olympic Park until 1923, at which point that venue was demolished and replaced by Offermann Stadium.[3]

Buffalo was awarded an expansion franchise by the Continental League of Major League Baseball in January 1960, and made plans to play at War Memorial Stadium beginning with the 1961 season. However, the league folded before the season began.[4] The Buffalo Bisons remained in the International League and began play at War Memorial Stadium in 1961, as Offermann Stadium had already been slated for demolition.[3]

In April 1968, Robert O. Swados and his investment group, which included George Steinbrenner, presented their bid for a Buffalo expansion franchise to the National League Expansion Committee.[5][6] This bid included plans for a $50 million domed stadium that was designed by the architects of the Astrodome and had a capacity of 45,000.[7] Buffalo was one of five finalists for the 1969 Major League Baseball expansion, but franchises were awarded to the Montreal Expos and San Diego Padres in May 1968.[5]

Erie County went on to modify the planned domed stadium to accommodate the Buffalo Bills, approving its construction as a 60,000-seat football venue in Lancaster that could also host baseball.[8] However, bids for the stadium in 1970 came in over budget, and the project stalled. Bills owner Ralph Wilson threatened to move the Bills if action was not taken to replace the aging War Memorial Stadium, forcing Erie County to abandon the domed stadium in favor of building open-air Rich Stadium in Orchard Park.[9][10] Major League Baseball had planned on relocating the struggling Washington Senators franchise to Buffalo, but when the domed stadium wasn't built it instead became the Texas Rangers.[11] The Buffalo Bisons moved mid-season in 1970 and became the Winnipeg Whips, leaving Buffalo without professional baseball.[12]

Planning and construction, 1978–1987

[edit]

Mayor James D. Griffin and an investment group purchased the Jersey City A's of the Double-A class Eastern League for $55,000 in 1978, and the team began play as the Buffalo Bisons at War Memorial Stadium in 1979.[13] This new franchise assumed the history of prior Buffalo Bisons teams that had played in the city from 1877 to 1970. Rich Products heir Robert E. Rich Jr. purchased the Bisons for $100,000 in 1983, and upgraded the team to the Triple-A class American Association in 1985 after buying out the Wichita Aeros for $1 million.[14][15] The Bisons began drawing record crowds with promotional tie-ins, most notably annual post-game concerts by The Beach Boys.[16][17]

Strong political support grew to replace the aging War Memorial Stadium with what was originally known as Downtown Buffalo Sports Complex.[18] The City of Buffalo originally hired HOK Sport to design a $90 million domed stadium with a capacity of 40,000 on 13 acres of land, but the project was scaled back after New York State only approved $22.5 million in funding instead of the $40 million requested.[19][20][21] A separate athletic facility to service the City Campus of Erie Community College was part of the proposed complex, and was eventually built several years later as the Burt Flickinger Center.[22]

St. John's Episcopal Church originally occupied what would become the venue's land at the corner of Washington Street and Swan Street, and Randall's Boarding House originally occupied the adjacent lot on Swan Street. Mark Twain famously was a resident of the boarding house while editor of the Buffalo Express.[23][24] Constructed between 1846 and 1848, the church remained in use until 1893 and was demolished in 1906.[25][26] The land then became the site of Ellsworth Statler's first hotel, Hotel Statler, in 1907.[25] It was later renamed Hotel Buffalo after Statler built a new hotel on Niagara Square in 1923 and sold his former location. Hotel Buffalo was demolished in 1968, and the land became a parking lot. The City of Buffalo would later acquire the land through eminent domain.[27]

HOK Sport (now known as Populous) designed the downtown venue as the first retro-classic ballpark in the world.[28] The open-air venue was designed to incorporate architecture from the neighboring Joseph Ellicott Historic District, most notably the Ellicott Square Building and Old Post Office.[29] The venue's exterior would be constructed from precast concrete, featuring arched window openings at the mezzanine level, rusticated joints, and inset marble panels.[30] Located close to Buffalo Memorial Auditorium and along the newly built Buffalo Metro Rail, the venue would be an attractive and accessible destination for suburban residents.[31] The same design firm would later bring this concept to Major League Baseball with Oriole Park at Camden Yards.[32]

The baseball field itself would feature a Kentucky Bluegrass playing surface and have dimensions that were designed to mirror those of pitcher-friendly Royals Stadium.[33] Buffalo Bisons management insisted the field have deep fences after War Memorial Stadium acquired a poor reputation for allowing easy home runs.[34] Roger Bossard, head groundskeeper of Comiskey Park, served as consultant for the project.[35]

The venue broke ground in July 1986, with structural engineering handled by Geiger Associates, and Cowper Construction Management serving as general contractor.[36][37] It was originally built with a seating capacity of 19,500, which at the time made it the third-largest stadium in Minor League Baseball.[28][38] This included a club level with seating for 3,500 and 38 luxury suites, general admission bleacher seating for 1,130 in right field, and a 250-seat restaurant with city and field views on the mezzanine level.[35][37][39] Rich Products already owned and operated local restaurants under their B.R. Guest brand, and they assumed operation of the venue's restaurant and concessions.[40]

The $42.4 million venue was mainly paid for with public funding. $22.5 million came from New York State, $12.9 million came from the City of Buffalo, $4.2 million came from Erie County, and $2.8 million came from the Buffalo Bisons.[41] The New York State funding was contingent on the Bisons signing a 20-year lease with the City of Buffalo for use of the venue, which they did just prior to groundbreaking.[42] The City of Buffalo and Erie County paid an additional $14 million for the construction of parking garages to service the venue and other downtown businesses.[41]

A planned second phase of construction was a seating expansion contingent on Buffalo acquiring a Major League Baseball franchise. The original design by HOK Sport called for a third deck to be added in place of the roof, expanding the venue's capacity from 19,500 to 40,000. In May 1987, it was estimated this expansion could be completed within one offseason at a cost of $15 million.[19]

Opening and reception, 1988–1989

[edit]Opening Day of the venue's inaugural season took place on April 14, 1988, and saw the Buffalo Bisons defeat the Denver Zephyrs 1–0.[43] Bob Patterson of the Bisons threw the first pitch against Billy Bates, and the lone score came from a Tom Prince home run.[44] Pam Postema, the first female umpire in the history of professional baseball, officiated the game.[45] Prior to the event, The Oak Ridge Boys performed "The Star-Spangled Banner" and both Mayor James D. Griffin and Governor Mario Cuomo threw ceremonial first pitches.[45][46]

The formal dedication of the venue took place on May 21, 1988, prior to the Buffalo Bisons defeating the Syracuse Chiefs in an interleague Triple-A Alliance game by a score of 6–5. Larry King threw the ceremonial first pitch and sat in on commentary with WBEN broadcasters Pete Weber and John Murphy.[47]

In their first year at the venue after moving from War Memorial Stadium, the Buffalo Bisons broke the all-time record for Minor League Baseball attendance by drawing 1,186,651 fans during the 1988 season.[48] The team had capped season ticket sales at 9,000 seats to ensure that individual game tickets would be available.[49]

The inaugural Build New York Award was given to Cowper Construction Management by the General Building Contractors of New York State for their work on the venue.[50]

The venue was lauded by mainstream media outlets, including feature stories by Newsday, New York Daily News, San Francisco Examiner, Sports Illustrated, The New York Times Magazine and Vancouver Sun.[51] Eric Brazil wrote in his San Francisco Examiner column that the venue, "just may be baseball's prototype for the 1990s and beyond".[52]

Pete McMartin wrote fondly of the venue in his June 1989 article for the Vancouver Sun, contrasting it with the recently opened SkyDome in Toronto:

It was a matter of philosophy. Toronto built an edifice: Buffalo embraced an idea. Toronto elevated technology over the game: Buffalo honored the past. Buffalo ended up with the better ballpark. It may be the best ballpark built since the construction of the game's holy triumvirate – Wrigley, Fenway and Briggs.[53]

MLB preparation and seating expansion, 1990–1995

[edit]

In anticipation of Buffalo being awarded a major league franchise, Robert E. Rich Jr. began establishing minor league farm teams for the Buffalo Bisons organization. Rich Jr. acquired the Double-A Wichita Pilots and founded the Class A Short Season Niagara Falls Rapids.[54][55] He renamed Wichita's team to the Wranglers and planned to upgrade their franchise to Triple-A upon the Bisons joining Major League Baseball.[56]

The proposed seating expansion to accommodate Major League Baseball was revised by HOK Sport to preserve the aesthetic of the roof, which would now be kept and raised to cover a third deck. In this new design, less seating would be built on the third deck, and instead a new right field seating structure would be built in front of the Exchange Street parking ramp.[57] In addition, expanded bleachers would be added in right field that could later be converted to permanent seating. Capacity after this expansion would increase from 19,500 to 41,530 at a cost of $30 million, but unlike the earlier design would take longer than a single offseason to complete.[58] Prior to the 1990 season, 1,400 bleacher seats and a standing-room only area within the third-base mezzanine were added at a cost of $1.34 million, increasing the stadium's capacity from 19,500 to 21,050.[59][60]

In September 1990, Bob Rich Jr. attempted to buy the Montreal Expos for $100 million and move the team to Buffalo, but owner Charles Bronfman declined his offer.[61] That same month, Rich Jr. and his investment group presented their bid for a Buffalo expansion franchise to the National League Expansion Committee.[62] Members of this investment group included Jeremy Jacobs, Larry King, Northrup R. Knox, Robert G. Wilmers, Robert O. Swados and Seymour H. Knox III.[63] It was reported that the investment group was prepared to fund $134 million in private capital required for expansion, which included the $95 million franchise fee and initial operating costs.[64] The largest share of the financial burden would fall on Rich Jr., who pledged a minimum of $10 million cash and the equity in his three minor league teams. Rich Jr. publicly voiced concerns in December 1990 that without a salary cap and revenue sharing, he would have to raise ticket prices to unaffordable levels while being unable to produce a competitive on-field product.[65] 27,000 major league season ticket commitments were made by April 1991, consisting of 18,000 paid seat deposits and 9,000 complimentary deposits awarded to the existing Bisons season ticket holders.[66] Buffalo was one of six finalists for the 1993 Major League Baseball expansion, but franchises were awarded to the Colorado Rockies and Florida Marlins in June 1991.[67] National League president Bill White later confirmed that Rich Jr. publicly questioning the league's financial structure sunk his bid.[68]

In their fourth year at the stadium, the Buffalo Bisons once again broke the all-time record for Minor League Baseball attendance by drawing 1,240,951 fans during the 1991 season.[69]

| All-Time Minor League Baseball Attendance Records[70] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Team | Year | Attendance |

| 1. | Buffalo Bisons | 1991 | 1,240,951 |

| 2. | Buffalo Bisons | 1988 | 1,186,651 |

| 3. | Buffalo Bisons | 1990 | 1,174,358 |

| 4. | Buffalo Bisons | 1992 | 1,134,488 |

| 5. | Buffalo Bisons | 1989 | 1,132,183 |

| 6. | Buffalo Bisons | 1993 | 1,079,620 |

| 7. | Louisville Redbirds | 1983 | 1,052,438 |

| 8. | Buffalo Bisons | 1994 | 982,493 |

| 9. | Buffalo Bisons | 1995 | 951,080 |

| 10. | Sacramento River Cats | 2001 | 901,214 |

Rich Jr. offered to let the Montreal Expos finish their home schedule at the venue in September 1991 after Olympic Stadium was damaged, but the team instead played their final 13 home games on the road.[71][72]

In June 1992, Rich Jr. attempted to buy the San Francisco Giants and move the team to Buffalo, but owner Bob Lurie declined his offer. The proposed name for the team would have been the New York Giants of Buffalo, as the franchise had previously played as the New York Giants from 1885 to 1957 in New York City.[61] That same month, the City of Buffalo chose to exercise an escape clause and buy back $24.2 million in federal bonds they had earmarked for expanding the venue to accommodate Major League Baseball.[73][74]

The 1988 to 1993 Buffalo Bisons seasons were the six highest-attended campaigns in Minor League Baseball history, with each season drawing over 1,000,000 fans.[70]

Prior to the 1994 season, a restaurant called Power Alley Pub was constructed under the bleachers in right-center field.[75] The restaurant provided seating with views of the field through the outfield wall.

Rich Jr. moved his Class A Short Season Niagara Falls Rapids after he was unable to secure repairs for the aging Sal Maglie Stadium. The team resumed play as the Jamestown Jammers in June 1994.[76]

In July 1994, Rich Jr. notified the Major League Baseball Expansion Committee that he was interested in pursuing a Buffalo expansion franchise.[77] However, he would retract this notification the following month after the 1994–95 Major League Baseball strike commenced.[78] Buffalo was withdrawn as a candidate for the 1998 Major League Baseball expansion, and franchises were awarded to the Arizona Diamondbacks and Tampa Bay Devil Rays in March 1995.[79]

Rich Jr. was offered an expansion franchise by the United Baseball League of Major League Baseball in November 1994 at a cost of $5 million, which would have played at the venue beginning with the 1996 season.[80] However, franchises were awarded in February 1995 to Long Island, Los Angeles, New Orleans, San Juan, Vancouver and Washington before the league folded without ever playing a game.[81][82]

The Buffalo Bisons considered sharing the venue with the Toronto Blue Jays for their 1995 season, as the Ontario Labour Relations Board prohibited non-union replacement players from competing at SkyDome during the 1994–95 Major League Baseball strike.[83] The Blue Jays instead chose to play at their spring training home of Dunedin Stadium, but the strike ended in April 1995 and the team returned to SkyDome.[84][85]

Alterations and seating reduction, 1996–2019

[edit]

A new outfield fence was erected prior to the 1996 season at a cost of $50,000 so that the venue's playing surface mirrored the dimensions of Jacobs Field. Left-center field was reduced from 384 feet to 371 feet, center field was reduced from 410 feet to 404 feet, right-center field was reduced from 384 feet to 367 feet, and the height of the center field fence was reduced from 15 feet to 8 feet. This change allowed the Cleveland Indians, Buffalo's major league affiliate, to better evaluate their prospects, while also making the park more hitter-friendly.[86]

The venue was home to the Buffalo Nighthawks of the Ladies Professional Baseball League before the league shut down mid-season in July 1998. The Nighthawks were in first place with an 11–5 record when the league folded, and were declared Eastern Division champions.[87]

The park's original four-color dot matrix scoreboard in center field was retrofitted with a 38-foot wide by 19-foot tall Daktronics LED video screen in 1999 at a cost of $1.2 million.[88]

The venue was home to the Buffalo Bulls of the National Collegiate Athletic Association in 2000.[89] The Bulls finished the season with a 12–35 record and moved to Amherst Audubon Field the following year.[90][91]

Major League Lacrosse staged an exhibition at the venue on August 11, 2000, as part of their Summer Showcase Tour.[92] Robert E. Rich Jr. planned to purchase a Major League Lacrosse franchise at a cost of $1 million to begin play at the venue in June 2001.[93][94] However, he withdrew support after determining that removing and replacing the pitcher's mound for lacrosse games would damage the field and put the Buffalo Bisons at a disadvantage.[95]

The 20-year lease between the Buffalo Bisons and City of Buffalo for use of the venue was renegotiated in January 2003, with the addition of funding from Erie County.[96]

Prior to the 2004 season, $5 million in renovations to the venue were completed, including removal of the stadium's right field bleachers and construction of a four-tier Party Deck in its place.[97] The removal of the bleachers decreased the stadium capacity from 21,050 to 18,025.[98]

A 4-foot wide by 8-foot tall digital billboard was installed on the corner of Washington Street and Swan Street before the 2007 season at a cost of $70,000.[99]

The 20-year lease between the Buffalo Bisons and City of Buffalo for use of the venue expired following the 2008 season, and the city began offering year-to-year leases to the team thereafter.[100]

The venue's luxury suites were consolidated and renovated beginning in 2010, reducing the total number from 38 to 26.[101] A conference suite was constructed on the first-base side of the stadium at a cost of $250,000, and the year-round suite can accommodate business gatherings of up to 40 people.[102]

Prior to the 2011 season, the park's original scoreboard in center field was removed and replaced by an 80-foot wide by 33-foot tall Daktronics high-definition LED video screen at a cost $2.5 million.[103] That same year, a new $970,000 field drainage system and a new $750,000 field lighting system were added to the venue.[104][105]

The venue was one of six that played home to the Empire State Yankees of the International League in 2012. The team was forced to play at alternate sites that season as PNC Field was undergoing renovations.[106] The Yankees finished the season with a 84–60 record and advanced to the International League playoffs.[107]

$500,000 was spent in improvements to the venue before the 2014 season, including a new sound system and the installation of new LED message boards down both baselines.[108]

A campaign to replace the park's original red seating with wider green seating began in 2014. The stadium's capacity was reduced from 18,025 to 17,600 when 3,700 seats were replaced prior to the 2015 season at a cost of $758,000.[109][110] 2,900 seats were replaced prior to the 2017 season, reducing capacity of the venue from 17,600 to 16,907.[111] 2,000 seats were replaced prior to the 2019 season, reducing capacity of the venue from 16,907 to 16,600.[112][113]

Following the 2019 season, protective crowd netting was installed throughout the venue at a cost of $475,000 to meet Major League Baseball safety standards.[114]

MLB residency and renovation, 2020–2021

[edit]

In June 2020, the Buffalo Bisons canceled their season at the venue due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[115] The Toronto Blue Jays, the Bisons' major league affiliate, announced the following month that they would play their 2020 season at the venue after the government of Canada denied them permission to play at Rogers Centre.[116][117] The venue's first Major League Baseball game took place on August 11, 2020, in which the Toronto Blue Jays defeated the Miami Marlins 5–4 in extra innings.[118] The Blue Jays finished the season with a 32–28 record, and advanced to the American League Wild Card Series.[119]

Major League Baseball and the Blue Jays organization jointly funded renovations of the venue prior to the 2020 season at a cost of $5 million.[120] Permanent upgrades included installation of LED field lighting, installation of instant replay technology, installation of Hawk-Eye for Statcast tracking, a resurfaced infield, and relocation of the home dugout to the third-base side of the stadium. Temporary facilities designed for the postponed MLB at Field of Dreams game were also utilized.[121][122]

The Blue Jays used the venue for part of their 2021 season due to the ongoing pandemic, after having started the season at TD Ballpark. The Bisons accommodated this residency by temporarily relocating to Trenton Thunder Ballpark in Trenton, New Jersey.[123] The venue drew higher attendance for MLB home games than the Miami Marlins, Oakland A's and Tampa Bay Rays drew at their own home venues.[124] The Blue Jays played 49 Major League Baseball games at the venue over the course of two seasons, tying Hiram Bithorn Stadium for the all-time record of most regular season games hosted by a non-home ballpark.[125]

The Bisons and Blue Jays jointly funded additional renovations of the venue prior to the 2021 season. These permanent upgrades included the installation of new light standards, new batting cages, new foul poles, a resurfaced outfield, and the relocation of both bullpens from foul territory to right-center field.[126] The renovated venue was named Professional Baseball Field of the Year in November 2021 by Sports Turf Managers Association.[127] The renovations were also nominated for Project of the Year at the 2021 Stadium Business Awards.[128]

Fire and proposed renovations, 2023–present

[edit]In September 2023, the venue sustained $600,000 in damage after a fire started in a mobile concession stand.[129][130]

The Buffalo Bisons hired a lobbying firm in November 2023 to seek funding from New York State for renovations that would improve the fan experience.[131]

Naming rights

[edit]Pilot Air Freight of Philadelphia purchased the 20-year naming rights to the venue in 1986.[132] The stadium would be named Pilot Field in exchange for the company paying the City of Buffalo $51,000 on an annual basis.[133] Their name was stripped from the venue by the City of Buffalo in March 1995 after Pilot Air Freight defaulted on payments.

The stadium was then known as Downtown Ballpark until July 1995, when local HMO North AmeriCare purchased the naming rights and the stadium became North AmeriCare Park (colloquially known as The NAP).[133][134] North AmeriCare agreed to pay the City of Buffalo $3.3 million over the course of 13 years.[135] The Dunn Tire chain of tire outlets assumed North AmeriCare's remaining contract with the City of Buffalo in May 1999, and the venue became Dunn Tire Park.[135]

Coca-Cola Bottling Company of Buffalo purchased the 10-year naming rights to the stadium in December 2008, and it was renamed Coca-Cola Field beginning with the 2009 season.[136] Sahlen's purchased the 10-year naming rights to the stadium in October 2018, and it was renamed Sahlen Field beginning with the 2019 season.[137]

Notable events

[edit]Baseball

[edit]

The annual National Old-Timers Baseball Classic was held at the venue from 1988 to 1990.[138][139][140]

The venue was host to the inaugural Triple-A All-Star Game on July 13, 1988.[141] It would later host the 25th-annual Triple-A All-Star Game on July 11, 2012.[142]

The June 3, 1990 game between the Buffalo Bisons and Oklahoma City 89ers, with a post-game concert by The Beach Boys, set the all-time single-game attendance record for baseball at the venue with 21,050 fans.[143] An August 30, 2002, game between the Buffalo Bisons and Rochester Red Wings would later match that record.[144]

The venue hosted an exhibition between Team USA and Korea on July 9, 1992, that saw Korea win the game 4–2.[145] The exhibition was part of Team USA's 30-game tour of both Cuba and the United States to promote their appearance in the 1992 Summer Olympics.[146]

Bartolo Colón of the Buffalo Bisons threw the venue's first and only no-hitter on June 20, 1997, against the New Orleans Zephyrs, sealing a 4–0 win.[147]

The Buffalo Bisons defeated the Richmond Braves at the venue on September 17, 2004 in Game 4 of their championship series to win the Governors' Cup by a score of 6–1.[148]

College baseball

[edit]The baseball events of the World University Games were held at the venue in July 1993.[149] The Gold medal game took place on July 16, 1993, and saw Cuba defeat South Korea 7–1.[150]

The venue hosted the inaugural Big Four Baseball Classic tournament from April 27, 2004, to April 28, 2004.[151] In the championship game, the Niagara Purple Eagles defeated the St. Bonaventure Bonnies 8–7 in extra innings to win the Bisons Cup.[152] The venue later hosted the second-annual Big Four Baseball Classic tournament from April 26, 2005, to April 27, 2005.[153] In the championship game, the St. Bonaventure Bonnies defeated the Canisius Golden Griffins 12–3.[154]

Softball

[edit]

Jim Kelly held his inaugural Jim Kelly Shootout and Carnival of Stars charity event at the venue on June 7, 1992. The event drew a crowd of 14,500 and raised $150,000 for the Kelly for Kids Foundation.[155] The second-annual Jim Kelly charity event, now renamed StarGaze, was held at the venue on June 13, 1993. The event drew a crowd of 10,000 and raised $100,000 for the Kelly for Kids Foundation.[156]

Micah Hyde held his inaugural Micah Hyde Charity Softball Game at the venue on June 2, 2019. The event drew a crowd of 2,500 and raised $40,000 for the Imagine for Youth Foundation.[157][158] The second-annual Micah Hyde Charity Softball Game on May 15, 2022, drew a crowd of 10,000 and raised $200,000 for the Imagine for Youth Foundation, with a portion of proceeds donated to families impacted by the 2022 Buffalo shooting.[159] The third-annual Micah Hyde Charity Softball Game on May 7, 2023 drew a crowd of 16,000 and raised $470,000 for the Imagine for Youth Foundation.[160] The fourth-annual Micah Hyde Charity Softball Game on May 19, 2024 drew a crowd of 14,771 and raised $625,000 for the Imagine for Youth Foundation.[161]

Concerts

[edit]

The Buffalo Bisons have presented a yearly post-game Summer Concert Series at the venue since 1988, featuring performances from national touring acts and the Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra.

The venue has regularly hosted local music festivals. WEDG presented their annual Edgefest at the venue in 1997 and 2003.[162][163] WYRK has presented their annual Taste of Country at the venue since its inception in 2001. The June 12, 2015, Taste of Country event headlined by Dierks Bentley set the all-time attendance record for concerts at the venue with 27,000 fans.[164] WKSE presented their annual Kiss the Summer Hello at the venue from 2001 to 2002, and again from 2009 to 2013.[165][166][167][168][169][170][171] The Great Guitar Gig took place at the venue on June 15, 2003, as part of the second-annual Buffalo Niagara Guitar Festival.[163]

The venue has also hosted national music festivals. Budweiser Superfest took place at the venue on July 7, 1989.[172] Bluestime Jam took place at the venue on August 29, 1995.[173] Counting Crows headlined a show at the venue on August 1, 2007, as part of their Rock 'n' Roll Triple Play Ballpark Tour.[174][175]

In film

[edit]Goo Goo Dolls filmed the music video for their debut single "There You Are" at the venue in 1990.[176]

A low-budget film called Angel Blues was shot at the venue in August 1993. It was directed by William Zabka and starred Michael Paloma, Loryn Locklin, Meredith Salenger, Richard Moll, David Johansen and Michael Horse.[177][178][179]

Professional wrestling

[edit]Ballpark Brawl was a series of post-game professional wrestling events produced by the Buffalo Bisons and promoted by Christopher Hill, their Director of Sales and Marketing between 2003 and 2007.[180] The promotion's Natural Heavyweight Championship paid homage to The Natural, which was filmed in Buffalo at War Memorial Stadium.

TNA Wrestling held BaseBrawl at the venue on June 18, 2011, an event headlined by Kurt Angle defeating Scott Steiner, with an appearance by Hulk Hogan.[181] A second BaseBrawl event on June 22, 2012 was headlined by Bobby Roode defeating Jeff Hardy to retain the TNA World Heavyweight Championship.[182]

Other events

[edit]

Reverend Billy Graham staged his Greater Buffalo-Niagara Crusade at the venue from August 1, 1988, to August 7, 1988.[183][184]

Opening Ceremonies for the Empire State Games took place at the venue on July 24, 1996. Buffalo native Todd Marchant was the event's keynote speaker.[185]

The venue was host to the annual Drum Corps International Tour of Champions, promoted locally as Drums Along the Waterfront, from its inception in 1997 to 2006.[186]

The venue began hosting the annual National Buffalo Wing Festival in 2002, featuring the U.S. National Buffalo Wing Eating Championship.[187] After moving to Highmark Stadium following the 2019 event, it will return to Sahlen Field beginning in 2025.[188]

The inaugural Harvard Cup Hall of Fame Game took place at the venue on September 28, 2002. The Kensington Knights defeated the Bennett Tigers 26–0 in the venue's first-ever football game.[189] The second-annual Harvard Cup Hall of Fame Game took place at the venue as a doubleheader on September 20, 2003. The Lafayette Violets defeated the Grover Cleveland Presidents 28–6, and the Hutch-Tech Engineers defeated the McKinley Macks 14–0.[190]

Special features

[edit]Dimensions

[edit]The venue's play is greatly affected by its orientation and susceptibility to the winds of nearby Lake Erie. Center field faces south-southeast, with a year-round 8 to 10 MPH breeze moving from the right field foul pole towards the left field foul pole.[191] Right-handed batters therefore tend to have the most success hitting balls into left field and left-center, although left-handed batters hitting opposite field at a high trajectory also see their balls carried out of the park.[191][192] The cozy field dimensions of 325 feet to left field and 371 feet to left-center aid the number of home runs hit in those directions.[193] A 60-foot tall chain-link fence in left field protects motor vehicles on Oak Street from being struck.[194] Cold winds in early months of the baseball season tend to prevent balls from exiting the park, while the warmer summer winds allow for greater carry.[195] In 2019, Baseball America ranked it as the third-best International League ballpark to hit home runs in.[195] The venue allowed 10% more runs than average during the 2020 Toronto Blue Jays season.[196]

Ground rules

[edit]

- A fair ball becoming lodged in the outfield fence padding is a ground rule double.

- A bounding fair ball striking the outfield fence padding and bouncing over the fence is an automatic double.

- A fair ball striking the foul pole caps or metal support piping beyond the outfield wall:

- is a home run if hit as a fly ball.

- is out of play if hit as a bounding ball.

- A bounding fair ball striking the unpadded cement wall to the immediate right and left of each foul pole is in play.

- A fair ball striking the bottom of the outfield fence is in play.[197]

Concessions

[edit]

Pub at the Park is a 250-seat bar and restaurant located within the venue's first-base mezzanine that features both indoor seating and outdoor patio seating with views of the field. It is open to the public for special events via an entrance on Washington Street, and exclusively to ticketholders with reservations on game days.[198] The restaurant was formerly known as Pettibone's Grille from 1988 to 2016.[199]

Concessions around the venue's concourse highlight local cuisine, with selections including beef on weck from Charlie the Butcher, craft beer from Consumer's Beverages and Resurgence Brewing Company, craft beer and wine from Southern Tier Brewing Company, hot dogs from Sahlen's, pierogies from Alexandra Foods, pizza from La Nova Pizzeria, pizza logs from Original Pizza Logs, and soft serve from Upstate Farms.[200] Coca-Cola brand soft drinks are also available throughout the stadium.[200]

The venue is cashless for concessions, with support for contactless payment and online food ordering with mobile payment.[201][202][203]

Tributes

[edit]

The Buffalo Bisons have customarily marked the landing spot of every home run their players have hit into the right field parking lot since the venue's inaugural season in 1988.[204] This feat is rarely accomplished because the balls have had to clear either the right field bleachers or the Party Deck that replaced them in order to reach the parking lot. Russell Branyan holds the record for most parking lot home runs, with three.[195]

Robert E. Rich Sr., the founder of Rich Products and father of Buffalo Bisons owner Robert E. Rich Jr., died in February 2006. His initials are inscribed on the press box, above the owner's suite, in tribute.[205] The venue hosted the annual Robert E. Rich Memorial Baseball Classic tournament between local high school teams from 2006 to 2008.[206][207][208]

Former Mayor of Buffalo James D. Griffin was posthumously honored by the Buffalo Common Council in July 2008 after they voted to change the venue's address to One James D. Griffin Plaza.[209]

A bronze sculpture of James D. Griffin titled The First Pitch, referencing his ceremonial first pitch at the venue's inaugural game, was unveiled outside the stadium in August 2012. The William Koch piece was commissioned by the Buffalo Bisons to honor Griffin's contributions in constructing the ballpark and bringing professional baseball back to Buffalo.[210]

Plaques honoring all members of the Buffalo Baseball Hall of Fame were previously displayed within the Hall of Fame and Heritage Room, which was built on the venue's third-base concourse in 2013.[211] It was removed in 2021 as part of stadium renovations, and has yet to reopen.[212]

The Buffalo Bisons hang a Championship Corner banner in left field that commemorates the team's many league and division championships, along with the retired numbers of Ollie Carnegie (6), Luke Easter (25), Jeff Manto (30) and Jackie Robinson (42).[213]

Retired numbers of former Toronto Blue Jays players Roberto Alomar (12) and Roy Halladay (32), along with the retired number of Jackie Robinson (42), were inscribed above the venue's press box for the 2020 season. In addition, the number of former Toronto Blue Jays player Tony Fernández (1) was inscribed on the venue's outfield fence to honor his recent passing.[214]

Transportation access

[edit]

Sahlen Field is located at the Elm Street exit (Exit 6) of Interstate 190, and within one mile of both the Oak Street exit of Route 33 and the Seneca Street exit of Route 5.[215]

A 816-space Allpro parking ramp is located behind right field on Exchange Street, and a pedestrian bridge over Washington Street connects it with a 457-space Allpro parking garage under the Seneca One Tower complex.[216][217] The Allpro parking garage provides a charging station.[218]

The venue is publicly served by Seneca Station of Buffalo Metro Rail, located one block West of the venue on Main Street.[219] It is also served by Buffalo–Exchange Street station of Amtrak, located directly across from the venue on Exchange Street.[220]

Niagara Frontier Transportation Authority maintains the Washington & Seneca bus stop located directly outside the venue's Seneca Street entrance, providing local service on Route 8 between downtown Buffalo and University Station.[221] Buffalo Metropolitan Transportation Center is located two blocks North of the venue on Ellicott Street and provides intercity bus service.[222]

Reddy Bikeshare maintains an automated station at the corner of Washington Street and Swan Street.[223]

Climate

[edit]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

[edit]- Specific

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ a b c Axisa, Mike (August 11, 2020). "MLB returns to Buffalo for first time in 105 years: Exploring the city's rich baseball history". CBSSports.com. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ a b "Buffalo Bisons: About". buffalo.bisons.milb.com. April 13, 2008. Archived from the original on April 13, 2008. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ Bailey, Budd (January 29, 2011). "This Day in Buffalo Sports History: The majors in Buffalo?". The Buffalo News.

- ^ a b Yates, Brock. "WARTS, LOVE AND DREAMS IN BUFFALO". Sports Illustrated Vault | SI.com.

- ^ Cichon, Steve (June 17, 2016). "Buffalo in the '60s: George Steinbrenner- 'The Boss' loved Buffalo". Buffalo News. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ York, N. New York Court of Appeals. Records and Briefs.: 67 NY2D 257, APPELLANTS REPLY BRIEF part , KENFORD COMPANY INC AND DOME STADIUM INC V COUNTY OF ERIE. p. 3247. Retrieved August 23, 2022.

- ^ "COUNTY PAYS $10 MILLION TO COTTRELL LONG FIGHT OVER DOME DRAWS TO A CONCLUSION". Buffalo News. September 28, 1989. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ "Herald-Journal - Google News Archive Search". news.google.com.

- ^ "Erie County Loses Dome Suit". The New York Times. August 5, 1984.

- ^ Gallivan, Peter (January 11, 2022). "Unknown Stories of WNY: A parade of plans, a look back at Bills stadium proposals of the past". wgrz.com. Retrieved June 11, 2022.

- ^ Bailey, Budd (June 4, 2011). "This Day in Buffalo Sports History, June 4, 1970: Buffalo loses Bisons baseball". Buffalo News. Retrieved August 23, 2022.

- ^ Moritz, Amy (July 14, 2017). "Buffalo's downtown ballpark: The house that Jimmy built". The Buffalo News.

- ^ "A Major League Effort for Buffalo". Los Angeles Times. September 6, 1988.

- ^ "The Daily Oklahoman from Oklahoma City, Oklahoma on September 8, 1984 · 72". Newspapers.com. September 8, 1984.

- ^ Class, Induction. "Robert E. Rich Jr. – Greater Buffalo Sports Hall of Fame". Greater Buffalo Sports Hall of Fame – Honoring men and women who have contributed to the welfare of amateur and professional sports in Greater Buffalo by performance, time, effort and/or financial support. Retrieved April 1, 2022.

- ^ Geller, Kathryn (June 25, 1989). "BEACH BOYS AND BISONS ARE A SUMMER TRADITION". Buffalo News. Retrieved April 1, 2022.

- ^ "Hoyt Organizes Stadium Support". Island Dispatch. Grand Island, N.Y. September 6, 1985. p. 21. ISSN 0892-2497. Retrieved May 29, 2022 – via NYS Historic Newspapers.

- ^ a b "Buffalo Is Building a Baseball Park". Los Angeles Times. United Press International. May 31, 1987. Retrieved April 11, 2022.

- ^ Roth, Stephen (April 12, 1999). "By design, they push limits of creativity". sportsbusinessdaily.com. Sports Business Journal.

- ^ "Buffalo's Efforts for Domed Stadium Are Dealt a New Blow". The New York Times. June 8, 1984.

- ^ Welch, Jamnes A. (November 14, 1989). "Still In Limbo! City's Athletic Facility". SUNY Erie Community College Student Voice. Buffalo, N.Y. p. 6. Retrieved May 29, 2022 – via NYS Historic Newspapers.

- ^ "NEW STUDY INDICATES TWAIN LIVED ON THE LINE IN PILOT FIELD". Buffalo News. July 22, 1989. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ "THE CITY TWAIN KNEW FUND-RAISER CELEBRATES AUTHOR'S LIFE". Buffalo News. August 14, 2002. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ a b "Ellsworth Statler in Buffalo". Western New York Heritage Press, Inc. 2007. Archived from the original on October 18, 2012. Retrieved February 20, 2014.

- ^ Cichon, Steve (September 12, 2018). "From 1880 to Today: View from St. Paul's Cathedral, 1870". Buffalo News. Retrieved August 23, 2022.

- ^ "Eminent domain played a roll in the development of two Buffalo sporting facilities - Buffalo Business First". www.bizjournals.com. Archived from the original on June 24, 2017.

- ^ a b Kingston, Rachel (April 4, 2010). "Buffalo Among the "Top Ten Places for a Baseball Pilgrimage"". WBEN. Buffalo. Archived from the original on April 8, 2010. Retrieved April 4, 2010.

- ^ "PILOT FIELD". Buffalo News. February 19, 1995. Retrieved June 4, 2022.

- ^ Garrity, John (October 12, 1987). "THE NEWEST LOOK IS OLD". Sports Illustrated Vault. Retrieved April 8, 2022.

- ^ Hamilton, Emily (July 29, 2020). "Want More Housing? Ending Single-Family Zoning Won't Do It". bloomberg.com. Bloomberg.

- ^ Kirst, Sean (April 12, 2018). "Sean Kirst: Buffalo's Pilot Field, an urban ballpark vision that swept nation". The Buffalo News.

- ^ DiCesare, Bob (July 9, 2012). "Buffalo's stadium set baseball standard". Buffalo News. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ DiCesare, Bob (April 5, 1999). "HOW THE BISONS GOT THEIR GROOVE BACK". Buffalo News. Retrieved June 9, 2022.

- ^ a b "Attendance Doubles In New Buffalo Stadium" (PDF). SportsTurf Magazine. July 27, 1988. Retrieved June 4, 2022.

- ^ "From the archives: Pilot Field". Buffalo News. March 2, 2019. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ a b "Field of dreams, November 1989" (PDF). Architectural Record. Retrieved April 11, 2022.

- ^ Buffalo Bisons Media Guide 2019, p. 133.

- ^ Kurtz, Howard (September 6, 1989). "AMERICAN JOURNAL". The Washington Post.

- ^ Baldwin, Richard E.; Lowery, Arch; Herbeck, Dan (November 15, 1994). "PILOT FIELD FOOD OPERATORS LAUNCH DINING-SPORTS COMPLEX". Buffalo News. Retrieved April 11, 2022.

- ^ a b Rodgers, Kim (June 11, 1988). "Oh, how Buffalo loves its jewel: City trying in earnest to get big-league club". The Indianapolis News. p. B-2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Fairbanks, Phil (April 4, 2000). "BISONS PLAYING HARDBALL BALLPARK LEASE COSTS TAXPAYERS AS TEAM PROSPERS". Buffalo News. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ Harrington, Mike (March 31, 1997). "There's No Place Like Home, Baseball in Buffalo Celebrates 10 Years at its Downtown Location". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Harrington, Mike (April 14, 2016). "Opening Day memories: April 14 is a special day in Bisons history". Buffalo News. Retrieved April 1, 2022.

- ^ a b "Mario Cuomo – Society for American Baseball Research".

- ^ Campbell, Jon (July 23, 2020). "Gov. Andrew Cuomo, defying history, hasn't thrown a first pitch. Is this the year?". New York State Team. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ "Bisons mourn passing of Larry King, who was set to join their MLB ownership group". The Buffalo News. January 23, 2021. Retrieved July 24, 2021.

- ^ "Buffalo Bisons Set Minor League Attendance Mark". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. August 20, 1988. Archived from the original on May 17, 2014. Retrieved May 15, 2014.

- ^ "BUFFALO MAKES MAJOR LEAGUE EFFORT". The Washington Post. September 5, 1988. Retrieved May 26, 2022.

- ^ "Ciminelli Cowper Co. Gets 'Build New York' Award". The Buffalo News. April 27, 1990.

- ^ Warner, Gene (August 23, 1989). "National Media Anything But Cool To Buffalo Baseball's 'Hot' Status Swirl of Coverage Boosts Scouting Report, Big-League Hopes for City". The Buffalo News.

- ^ "And Here's The Pitch". The Buffalo News. August 11, 1989.

- ^ McMartin, Pete (June 5, 1989). "Buffalo ball park shames Skydome". The Vancouver Sun.

- ^ "The Odessa American from Odessa, Texas on October 12, 1988 · 25". Newspapers.com. October 12, 1988. Retrieved March 28, 2022.

- ^ Baldwin, Richard (June 17, 1989). "IT'S 'PLAY BALL!' AS NIAGARA FALLS RAPIDS BEAT PIRATES IN SAL MAGLIE STADIUM DEBUT". Buffalo News. Retrieved March 28, 2022.

- ^ "As Fans Flock to Big Time Stadium, Buffalo Takes Aim at Big Leagues". The New York Times. June 20, 1989. Retrieved March 28, 2022.

- ^ Collison, Kevin; Hammersley, Margaret (November 30, 1989). "Bisons Unveil Plans To Increase Pilot Field Capacity To 41,530 Upper Tier Would Be Added, Bleachers Converted". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Cardinale, Anthony; Collison, Kevin; Raeke, Carolyn (December 1, 1989). "NEW PLAN DOUBLES STADIUM EXPANSION COST". Buffalo News. Retrieved April 11, 2022.

- ^ Heaney, James; Turner, Douglas (January 17, 1990). "Pilot Field Expansion Clears Council Vote Also Backs Architectural Study of Facility Next To War Memorial Site". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Buffalo Bisons Media Guide 2019, p. 134.

- ^ a b Felser, Larry (August 16, 1992). "Rich Says Battle to Obtain Big League Franchise Isn't Over". The Buffalo News.

- ^ "Summer Ends at Pilot Field; Rich's Investor Group Buoys Big League Quest". The Buffalo News. September 6, 1990.

- ^ "14 CO-INVESTORS, RICHES SHARE A TEAM SPIRIT". Buffalo News. December 19, 1990. Retrieved April 12, 2022.

- ^ Besecker, Aaron; Heaney, James; Allen, Carl (December 9, 1990). "BASEBALL COST GOING OUT OF SIGHT TAXPAYERS FACE PAYING BIG SHARE OF $230 MILLION". Buffalo News. Retrieved April 12, 2022.

- ^ DiCesare, Bob (March 23, 1991). "PAINFUL TRUTH STARING AT RICH: BUFFALO'S MARKET IS TOO SMALL". Buffalo News. Retrieved April 10, 2022.

- ^ "HIPP D.C. EXPANSION GROUP HAS ENOUGH MONEY FOR TEAM". The Washington Post. April 24, 1991. Retrieved May 27, 2022.

- ^ Chass, Murray (June 11, 1991). "Baseball Ready to Add Miami and Denver Teams". The New York Times.

- ^ White, B.; Mays, W. (2011). Uppity: My Untold Story About The Games People Play. Grand Central Publishing. p. 176. ISBN 978-0-446-56418-2. Retrieved April 12, 2022.

- ^ Bailey, Budd (August 19, 2011). "This Day in Buffalo Sports History: Packing them in". The Buffalo News.

- ^ a b Buffalo Bisons Media Guide 2019, p. 104.

- ^ "The Major League dream of Bob and Mindy Rich is, briefly, coming true". Buffalo News. August 9, 2020. Retrieved April 24, 2022.

- ^ "BASEBALL; Home Unsafe, Expos Move". The New York Times. September 14, 1991. Retrieved April 24, 2022.

- ^ "Pilot Field Funds Eyed for Arena Plan Would Finance Sabres' New Home with $24 Million Raised to Expand Stadium". The Buffalo News. February 22, 1992.

- ^ "Griffin Rejects Shift of Pilot Field Funds to New Sports Arena Decision Called 'Slight Setback'". The Buffalo News. May 2, 1992.

- ^ Northrop, Milt (April 13, 1994). "PILOT ISN'T A STADIUM STUCK IN 'PARK' FROM MENU TO MASCOT'S PAL, BISONS' HOME WILL HAVE DIFFERENT LOOK". Buffalo News. Retrieved April 22, 2022.

- ^ Warner, Gene (June 12, 1994). "IN A TALE OF TWO BASEBALL CITIES, FALLS' LOSS IS JAMESTOWN'S GAIN". Buffalo News. Retrieved March 28, 2022.

- ^ DiCesare, Bob (July 16, 1994). "Despite Threat of Strike, Expansion Talk Surfacing". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Gaughan, Mark (August 12, 1994). "Rich Says No Thanks To Big Leagues Unrest, Economics Temper Present Interest of Herd Owner". The Buffalo News.

- ^ "MLB expands to Phoenix and Tampa". UPI. March 9, 1995. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ DiCesare, Bob (November 2, 1994). "RICH PLAYS WAIT-AND-SEE ON NEW LEAGUE". Buffalo News. Retrieved March 24, 2022.

- ^ "THE UNITED BASEBALL LEAGUE UNVEILS ITS FRANCHISE PLAN". Sports Business Journal. February 15, 1995. Retrieved March 24, 2022.

- ^ Wise, A.N.; Meyer, B.S. (1997). International Sports Law and Business. Springer Netherlands. p. 636. ISBN 978-90-411-0977-4. Retrieved March 24, 2022.

- ^ Harrington, Mike (January 21, 1995). "PILOT FIELD UNLIKELY SITE IF JAYS MUST MOVE GAMES". Buffalo News. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Sullivan, Paul (March 26, 1995). "THE TORONTO BLUE JAYS MAY OPEN THE SEASON IN A 6,218-SEAT BALLPARK. IT'S OBVIOUS . . ". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ "BASEBALL STRIKE ENDS". The Washington Post. April 3, 1995. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ "Fences Moving at North Americare Park This Summer". The Buffalo News. December 19, 1995.

- ^ Starosielec, Mark (July 29, 1998). "Gates Close On Women's Baseball". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Harrington, Mike (November 6, 1998). "HERD WILL BE LIGHTING UP A NEW SCOREBOARD IN 1999". Buffalo News. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ Graham, Tim (March 22, 2000). "BASEBALL, SOFTBALL RETURN TO UB AFTER 13-YEAR HIBERNATION". Buffalo News. Retrieved May 24, 2022.

- ^ "2017 UB Baseball Media Guide". Issuu. February 10, 2017. Retrieved May 24, 2022.

- ^ "May 10, 2001-Vol32n31: Sports Recap". University at Buffalo. May 10, 2001. Retrieved May 24, 2022.

- ^ Borrelli, Tom (August 11, 2000). "LACROSSE TOUR ROLLS INTO DUNN TIRE PARK". Buffalo News. Retrieved March 24, 2022.

- ^ Borrelli, Tom; Bailey, Budd (August 19, 2000). "BUFFALO PLAYING THE WAITING GAME". Buffalo News. Retrieved April 8, 2022.

- ^ Borrelli, Tom; Bailey, Budd (May 13, 2000). "NEW LEAGUE GEARING UP FOR BUFFALO". Buffalo News. Retrieved March 28, 2022.

- ^ Harrington, Mike (August 12, 2000). "INDIANS EXPECT TO RAID BISONS ROSTER ON SEPT. 1". Buffalo News. Retrieved April 8, 2022.

- ^ "Off-season Wrap-up". OurSports Central. February 20, 2003.

- ^ Pignataro, T.J. (April 17, 2004). "Party Deck Helps Revive Spirit at BallPark's Opener". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Buffalo Bisons Media Guide 2019, p. 137.

- ^ Davis, Henry L.; Linstedt, Sharon (March 3, 1007). "Bisons to pitch the team's promotions with video billboard outside ballpark". Buffalo News. Retrieved March 30, 2022.

- ^ Williams, Deidre (April 4, 2017). "City, Bisons agree to 3-year lease extension". Buffalo News. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ "Renovation Project Yields Suite Results". MiLB.com. February 1, 2012. Retrieved September 4, 2021.

- ^ Fink, James (May 26, 2010). "Bringing the boardroom to the ballpark". Business First. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ Arrington, Blake (March 30, 2011). "HD Scoreboard Highlights What's New". Minor League Baseball. Archived from the original on May 17, 2014. Retrieved May 15, 2014.

- ^ "Bisons to install new $2.5M videoboard - Buffalo Business First". www.bizjournals.com. Archived from the original on January 24, 2011.

- ^ Harrington, Mike (January 13, 2011). "Bisons getting HD scoreboard, new lights". The Buffalo News.

- ^ "Rochester puts out welcome mat for SWB Yankees". Ballpark Digest. April 18, 2012. Retrieved June 8, 2022.

- ^ "Yankees'". OurSports Central. September 8, 2012. Retrieved August 25, 2022.

- ^ Harrington, Mike (February 24, 2014). "Bisons to Unveil New Message Boards, Sound System on Opening Day at Coca-Cola Field". The Buffalo News. Archived from the original on May 17, 2014. Retrieved May 15, 2014.

- ^ "Bisons, City of Buffalo Announce Installation of New Seats in Special Reserved Sections". Minor League Baseball. August 22, 2014. Archived from the original on April 21, 2015. Retrieved March 26, 2015.

- ^ Harrington, Mike (August 22, 2014). "Updated: Bisons to Replace 3,700 Seats As Phase I to 'overhaul' of Coca-Cola Field". The Buffalo News. Archived from the original on April 8, 2015. Retrieved March 26, 2015.

- ^ "Bisons unveil 2017 schedule & announce Phase 2 of ballpark seating project". Minor League Baseball. August 22, 2016. Archived from the original on October 2, 2016. Retrieved September 28, 2016.

- ^ Fink, James (March 23, 2019). "Buffalo Bisons freshen the ballpark lineup for 2019". Business First. Retrieved March 25, 2019.

- ^ Harrington, Mike (April 2, 2019). "Plenty of new amenities around Sahlen Field, International League". Buffalo News. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ "Home of the Buffalo Bisons set to be spruced up". Buffalo News. April 5, 2022. Retrieved August 23, 2022.

- ^ "Bisons will not play in 2020 as Minor League Baseball seasons are canceled". milb.com. June 30, 2020.

- ^ Vera, Amir; Ly, Laura; De La Fuente, Homero (July 18, 2020). "Canada denies Toronto Blue Jays' request to play home games due to pandemic". CNN.

- ^ Davidi, Shi (July 24, 2020). "Blue Jays to play majority of home games at Buffalo's Sahlen Field". Sportsnet.ca.

- ^ Davidi, Shi (August 11, 2020). "Blue Jays christen Buffalo home with walk-off win over Marlins". Sportsnet.ca.

- ^ "Toronto Blue Jays Team History & Encyclopedia". Baseball-Reference.com. May 23, 2022. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ Fink, James (September 22, 2020). "What MLB personnel see near Sahlen Field: $340M in development". wgrz.com. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ Harrington, Mike (July 24, 2020). "What has to be done to get Sahlen Field ready for MLB, Blue Jays". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Zwelling, Arden (May 29, 2022). "How Blue Jays transformed Sahlen Field into their temporary home". Sportsnet.ca. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ "Bisons to begin 2021 season playing home games in Trenton, NJ". MiLB.com. May 30, 2022. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ Hunter, Ian (July 23, 2021). "Blue Jays games in Buffalo outdraw three other MLB teams in attendance - Offside". Daily Hive Vancouver. Retrieved April 6, 2022.

- ^ Bisons, Buffalo (January 17, 2022). "STMA names Sahlen Field 'Professional Baseball Field of the Year'". MiLB.com. Retrieved January 17, 2022.

- ^ "What's new at Sahlen Field for the Blue Jays". Buffalo News. June 1, 2021. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ "STMA names Sahlen Field 'Professional Baseball Field of the Year'". MiLB.com. November 29, 2021. Retrieved November 29, 2021.

- ^ "#SBA21 AWARDS: 2021 Finalists Announced". TheStadiumBusiness Summit. October 27, 2021. Retrieved November 12, 2021.

- ^ "Sahlen Field fire causes $600K in damage; Bisons game will be played". News 4 Buffalo. September 1, 2023. Retrieved September 1, 2023.

- ^ "Bisons game will still be happening Friday night despite fire damages". wgrz.com. September 1, 2023. Retrieved September 1, 2023.

- ^ "Buffalo Bisons hire firm to push state to pay for renovations to the ballpark". wgrz.com. November 6, 2023. Retrieved November 7, 2023.

- ^ "Pilot Air's revenues are flying high". The Philadelphia Inquirer. June 29, 1987.

- ^ a b Bailey, Budd (March 2, 2011). "This Day in Buffalo Sports History, March 2, 1995: Pilot Field's name changed". The Buffalo News.

- ^ "IN ARENA OF IDEAS, THIS ONE'S A HARD ONE". Greensboro News and Record. May 18, 2022. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- ^ a b Fairbanks, Phil (May 4, 1999). "Dunn Tire is Looking to Pay Ballpark Figure of 2.5 Million". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Harrington, Mike (December 17, 2008). "Goodbye, Dunn Tire Park. Hello, Coca-Cola Field!". The Buffalo News. Archived from the original on February 3, 2009. Retrieved December 17, 2008.

- ^ "Sahlen Field – the new home of the Herd". Archived from the original on October 10, 2018. Retrieved October 9, 2018.

- ^ "NL Old Timers Win". Hutchinson News. Associated Press. June 21, 1988.

- ^ Harrington, Mike; Summers, Robert J. (June 18, 1989). "Old-Timers Game Represents Classic Case of Nostalgia". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Harrington, Mike; Summers, Robert J. (June 25, 1990). "Baseball's Greats Set For Third -- Perhaps Last -- Hurrah At Pilot". The Buffalo News.

- ^ "Triple-A All-Star Game Results (1988-1992)". tripleabaseball.com. Archived from the original on July 9, 2019. Retrieved July 17, 2020.

- ^ "Triple-A All-Star Game Results (2008-2012)". tripleabaseball.com.

- ^ DiCesare, Bob (June 3, 1990). "Sloppiness Foils Herd in 7-6 Loss". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Moritz, Amy (August 31, 2002). "Herd's Goelz Shines In Packed House". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Harrington, Mike (July 10, 1992). "USA SLUMP CONTINUES AGAINST KOREA AMERICANS MANAGE JUST FIVE HITS IN LOSS AT PILOT FIELD". Buffalo News. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ "Team USA 1992 Media Guide" (PDF). USA Baseball. April 15, 2022. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 15, 2022. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ Buffalo Bisons Media Guide 2019, p. 135.

- ^ "Bisons Win 2004 Governors' Cup". oursportscentral.com. September 17, 2004.

- ^ "WORLD UNIVERSITY GAMES; Cuban Player Takes Intentional Walk". The New York Times. July 11, 1993.

- ^ DiCesare, Bob (July 17, 1993). "Unmatched Cuba Runs, Hits, Fields Its Way To Gold Medal In Baseball". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Athletics, Canisius College (October 30, 2003). "Inaugural Big Four Baseball Classic To Be Held at Dunn Tire Park". Canisius College Athletics. Retrieved March 26, 2022.

- ^ Athletics, Niagara University (April 28, 2004). "Niagara Defeats St. Bonaventure, Wins Inaugural Big Four Baseball Classic". Niagara University Athletics. Retrieved March 26, 2022.

- ^ "BONA, CANISIUS WIN AT BIG 4 CLASSIC". Buffalo News. April 27, 2005. Retrieved March 26, 2022.

- ^ Moritz, Amy (April 28, 2005). "BONA MAKES GRIFFS PAY FOR MISTAKES". Buffalo News. Retrieved March 26, 2022.

- ^ Northrop, Milt (June 8, 1992). "Unlikely Stars Steal The Limelight In Shootout Bills Linebacker, Backup QBs Upstage NFL's Finest At Kelly Charity Carnival". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Liguori, Aaron J.; Habuda, Janice L. (June 14, 1993). "Kids Come Up Winners as Celebrities Pitch In And Make Stargaze '93 A Day To Remember". The Buffalo News.

- ^ "Bills chemistry on display at Micah Hyde's Charity Softball Game". www.buffalobills.com.

- ^ Carucci, Vic (June 3, 2019). "Bills bond under sun at Micah Hyde's charity softball game". Buffalo News. Retrieved March 25, 2022.

- ^ Getzenberg, Alaina (May 15, 2022). "Hyde uses charity game to aid shooting victims". ESPN.com. Retrieved May 24, 2022.

- ^ "Sold-out charity softball game 'truly remarkable' to Bills safety Micah Hyde". Buffalo News. May 3, 2023. Retrieved May 7, 2023.

- ^ Skurski, Jay (May 19, 2024). "Jordan Poyer has a chance to say goodbye at Micah Hyde's charity softball game". Buffalo News. Retrieved May 20, 2024.

- ^ "Over The Weekend". The Buffalo News. June 30, 1997.

- ^ a b "Summer Concerts 2003". The Buffalo News. May 23, 2003.

- ^ O'Shei, Tim (June 13, 2015). "Taste of Country serves up a six-course delight". The Buffalo News.

- ^ "IL News and Notes". oursportscentral.com. International League. April 26, 2001.

- ^ Miers, Jeff (May 24, 2002). "Summer Smooch". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Sweeney, Joe (June 4, 2009). "Pop music fans enjoy first kiss of summer". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Sweeney, Joe (June 6, 2010). "This summer's officially Kissed". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Sweeney, Joe (June 5, 2011). "Time to say 'Hello' to summer music season". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Gallivan, Seamus (June 3, 2012). "Kiss show is high-energy, sugary sweet". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Gallivan, Seamus (June 30, 2013). "Teens and tweens kiss the summer hello". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Anderson, Dale (December 24, 1989). "1989: A Final Word From Our Critics". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Santella, Jim (August 30, 1995). "It's Hard To Be Blue When B.B. King and Friends Come to Town". The Buffalo News.

- ^ "Counting Crows to play Dunn Tire Park". MiLB.com. May 18, 2007.

- ^ Schobert, Christopher (August 2, 2007). "A comfortable lineup of 90s nostalgia". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Nason, Geoff (May 4, 2016). "Goo Goo Dolls' Rzeznik Recalls Pilot Field During Interview On MLB Network". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Harrington, Mike (August 28, 1993). "A Special Night At Pilot Just Could Be A 'Natural'". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Archerd, Army (August 24, 1994). "Chanel gets endorsement from Monroe". Variety.

- ^ Germain, David (August 28, 1993). "Buffalo honors The Natural". Montreal Gazette.

- ^ "Ballpark Brawl VII with Sergeant Slaughter on August 27". MiLB.com. August 24, 2006.

- ^ "TNA BASEBRAWL IN BUFFALO, NY LIVE REPORT". PWInsider.com. June 19, 2011. Retrieved August 23, 2022.

- ^ "6/22 TNA BASEBRAWL IN BUFFALO, NY RESULTS". PWInsider.com. June 23, 2012. Retrieved August 23, 2022.

- ^ S., Michael; T., Patricia (July 30, 1988). "Syracuse Post Standard Archives, Jul 30, 1988, p. 6". NewspaperArchive.com. Retrieved March 25, 2022.

- ^ Chismar, Janet (July 17, 2012). "Buffalo Ready for Rock the Lakes". Billy Graham Evangelistic Association.

- ^ Cardinale, Anthony; Herbeck, Dan (July 25, 1996). "Curtain Rises On Empire State Games". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Crawley, Eric (July 8, 1997). "DRUM ROLL, PLEASE! A BOOMING EVENT". Buffalo News. Retrieved March 26, 2022.

- ^ "National Buffalo Wing Festival pivots, becomes 'America's Greatest Chicken Wing Party' for 2020". WKBW. July 8, 2020. Retrieved April 5, 2022.

- ^ Campbell, Brian (December 10, 2024). "National Buffalo Wing Festival to move back to Sahlen Field in 2025". spectrumlocalnews.com. Retrieved December 11, 2024.

- ^ Salzman, Bob; Monnin, Mary Jo (September 29, 2002). "A NIGHT OF HARVARD CUP MEMORIES". Buffalo News. Retrieved March 25, 2022.

- ^ Rodriguez, Miguel (September 21, 2003). "DEFENSES LIFT HUTCH-TECH, LAFAYETTE". Buffalo News. Retrieved March 25, 2022.

- ^ a b Spencer, Crosby (September 20, 2020). "2020 Park Factors for the Seven New MLB Parks - RotoFanatic". RotoFanatic. Archived from the original on October 6, 2020. Retrieved August 23, 2022.

- ^ Dykstra, Sam (August 26, 2022). "Toolshed: What Buffalo move means for bats, arms". MiLB.com. Retrieved August 26, 2022.

- ^ Lerner, Danielle (June 4, 2021). "Buffalo's Sahlen Field brings a new experience for Astros". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved August 26, 2022.

- ^ DiCesare, Bob (March 15, 1989). "BISONS FIELD A RASH OF IDEAS TO BABY THEIR FANS". Buffalo News. Retrieved June 9, 2022.

- ^ a b c "Early returns make Sahlen Field a big-league bandbox for home runs". Buffalo News. August 20, 2020. Retrieved August 26, 2022.

- ^ Bannon, Mitch (June 1, 2021). "A Look at the New Sahlen Field in Buffalo". Sports Illustrated Toronto Blue Jays News, Analysis and More. Retrieved August 26, 2022.

- ^ "Ground Rules". MLB.com. May 11, 2022. Archived from the original on May 11, 2022. Retrieved August 27, 2022.

- ^ "Bisons Consumer's Pub at the Park". MiLB.com. March 30, 2022. Retrieved March 30, 2022.

- ^ Galarneau, Andrew Z. (July 6, 2017). "Consumer's Pub at the Park replaces Pettibones at the stadium". The Buffalo News.

- ^ a b "Sahlen Field Concessions". MiLB.com. March 31, 2023. Retrieved March 31, 2023.

- ^ "Sahlen Field to be cashless for Buffalo Bisons games in 2024 for concessions, merchandise, vending & restaurant purchases". MiLB.com. March 19, 2024. Retrieved March 19, 2024.

- ^ Palmer, Megan (August 18, 2021). "SpotOn Home Run with Fan-Focused Tech Stack at Sahlen Field". Heart & Hustle. Retrieved March 30, 2022.

- ^ "With a full season on the schedule, Bisons mixing staples with new twists". Buffalo News. March 29, 2022. Retrieved March 30, 2022.

- ^ Lysowski, Lance. "Blue Jays briefs: Rowdy Tellez, 'homeless' Jays power past Rays". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Thompson, Carolyn (February 18, 2006). "Robert E. Rich Sr., at 92; invented nondairy topping". The Boston Globe.

- ^ "High School Extra / News & notes". Buffalo News. April 24, 2006. Retrieved August 24, 2022.

- ^ "Spartans win Baseball Classic, 9-8, in Nine Innings". MiLB.com. May 16, 2007. Retrieved August 24, 2022.

- ^ "St. Mary's Wins Rich Baseball Classic". MiLB.com. April 20, 2008. Retrieved August 24, 2022.

- ^ Zremski, Jerry; Meyer, Brian (July 16, 2008). "Russert, Griffin names headed for public spaces Bills' stadium road; baseball park plaza". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Fetouh, Omar (August 17, 2012). "Jimmy Griffin statue unveiled at Coca Coca Field". news.wbfo.org. WBFO NPR.

- ^ Buffalo Bisons Media Guide 2019, p. 92.

- ^ Harrington, Mike (August 22, 2022). "Inside Baseball: Ben Francisco's consistency lands him in Buffalo Hall". Buffalo News. Retrieved August 13, 2024.

- ^ "Bisons to Retire Manto's no. 30 in August Ceremony". The Buffalo News. May 18, 2001.

- ^ Harrington, Mike (August 11, 2020). "Play ball: Buffalo is back in the majors as Blue Jays open series". The Buffalo News.

- ^ Lingo, W.; Badler, B.; Blood, M.; Cooper, J.J.; Eddy, M.; Fitt, A. (2008). Baseball America Directory 2008: Your Definitive Guide to the Game. Baseball America. p. 116. ISBN 978-1-932391-20-6. Retrieved August 23, 2022.

- ^ Epstein, Jonathan D. (February 26, 2016). "Seneca Tower ramp goes up for sale March 3". Buffalo News. Retrieved August 25, 2022.

- ^ "Jemal seeks to take control of Seneca One underground garage from city". Buffalo News. November 29, 2021. Retrieved March 19, 2022.

- ^ Williams, Deidre (May 9, 2017). "Charging stations for electric cars coming to downtown ramps". Buffalo News. Retrieved August 25, 2022.

- ^ "Heading to an Event". Metro Bus & Rail. Retrieved March 21, 2022.

- ^ "New Rail Station Opens in Downtown Buffalo – Great American Stations". Great American Stations – Revitalizing America's Train Stations. November 12, 2020. Retrieved March 25, 2022.

- ^ "#8 - Main". Metro Bus & Rail. Retrieved April 24, 2022.

- ^ "Intercity Buses". GO Buffalo Niagara. September 4, 2018. Retrieved March 26, 2022.

- ^ "Reddy Bikeshare". Reddy Bikeshare. October 29, 2021. Retrieved March 21, 2022.

- ^ "Climate Charts: Buffalo, New York". climate-charts.com.

- General

- "2019 Buffalo Bisons Media Guide" (PDF). Buffalo Bisons. Minor League Baseball. Retrieved August 2, 2020.

Further reading

[edit]- Overfield, Joseph M. The Seasons of Buffalo Baseball 1857-2020 (Billoni Associates Publishing, 2020). ISBN 9780578757049

- Rich, Bob. The Right Angle: Tales from a Sporting Life (Prometheus Books, 2011). ISBN 9781616144289

- Violanti, Anthony. Miracle in Buffalo: How the Dream of Baseball Revived a City (St. Martin's Press, 1991). ISBN 9780312048785

External links

[edit]| Events and tenants | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by | Home of the Buffalo Bisons 1988 – 2019 2021 – present |

Succeeded by Trenton Thunder Ballpark

Present |

| Preceded by | Host of the Old-Timers Baseball Classic 1988 – 1990 |

Succeeded by Final event

|

| Preceded by Inaugural event

Spring Mobile Ballpark |

Host of the Triple-A All-Star Game 1988 2012 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by Inaugural event

|

Host of StarGaze 1992 – 1993 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | World University Games venue 1993 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by Inaugural

|

Home of the Buffalo Nighthawks 1998 |

Succeeded by Final

|

| Preceded by Inaugural

|

Home of the Buffalo Bulls 2000 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by Inaugural event

Highmark Stadium |

Host of the National Buffalo Wing Festival 2002 – 2019 2025 – present |

Succeeded by Highmark Stadium

Present |

| Preceded by | Home of the Toronto Blue Jays 2020 2021 |

Succeeded by |

- 1988 establishments in New York (state)

- Baseball venues in New York (state)

- Buffalo Bisons (minor league)

- Buildings and structures in Buffalo, New York

- Defunct college baseball venues in the United States

- Defunct Major League Baseball venues

- International League ballparks

- Minor league baseball venues

- Music venues completed in 1988

- Music venues in New York (state)

- Populous (company) buildings

- Sports venues completed in 1988

- Sports venues in Buffalo, New York

- Sports venues in Erie County, New York

- Sports venues in New York (state)

- Toronto Blue Jays stadiums

- Tourist attractions in Buffalo, New York