Saxe-Weimar

Duchy of Saxe-Weimar Herzogtum Sachsen-Weimar (German) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1572–1809 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Status | State of the Holy Roman Empire, then State of the Confederation of the Rhine | ||||||||

| Capital | Weimar | ||||||||

| Common languages | |||||||||

| Religion | Protestant | ||||||||

| Government | Feudal monarchy | ||||||||

| Historical era | Early modern period | ||||||||

• Division of Erfurt | 1572 | ||||||||

| 1602 | |||||||||

| 1640 | |||||||||

| 1672 | |||||||||

| 1741 | |||||||||

| 1809 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Germany | ||||||||

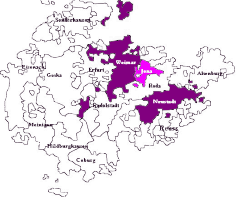

Saxe-Weimar (German: Sachsen-Weimar) was one of the Saxon duchies held by the Ernestine branch of the Wettin dynasty in present-day Thuringia. The chief town and capital was Weimar. The Weimar branch was the most genealogically senior extant branch of the House of Wettin.

History

[edit]Division of Leipzig

[edit]In the late 15th century much of what is now Thuringia, including the area around Weimar, was held by the Wettin Electors of Saxony. According to the 1485 Treaty of Leipzig, the Wettin lands had been divided between Elector Ernest of Saxony and his younger brother Albert III, with the western lands in Thuringia together with the electoral dignity going to the Ernestine branch of the family.[1]

Ernest's grandson Elector John Frederick I of Saxony forfeited the electoral dignity in the 1547 Capitulation of Wittenberg, after he had joined the revolt of the Lutheran Schmalkaldic League against the Habsburg emperor Charles V, was defeated, captured and banned. Nevertheless, according to the 1552 Peace of Passau he was pardoned and allowed to retain his lands in Thuringia. Upon his death in 1554, his son John Frederick II succeeded him as "Duke of Saxony", residing at Gotha. His attempts to regain the electoral dignity failed: in the course of the 1566 revolt instigated by the robber baron Wilhelm von Grumbach, the duke was banned and imprisoned for life by Emperor Maximilian II.

Division of Erfurt

[edit]John Frederick II was succeeded by his younger brother John William at Weimar, who in a short time also fell out of favour with the emperor by his alliance with King Charles IX of France. In 1572 Maximilian II enforced the Division of Erfurt, whereby the Ernestine lands were divided among Duke John William and the two surviving sons of imprisoned John Frederick II. John William retained the Duchy of Saxe-Weimar, while his minor nephews received the southern and western territories around Coburg and Eisenach.

This division was the first of numerous partitions; over the next three centuries the lands were divided when dukes had more than one son to provide for and re-combined when dukes died without direct heirs, but all of the lands stayed in the Ernestine branch of the Wettin family. As a result, the Duchy of Saxe-Weimar shrank and grew more than once. The Thuringian states throughout this period typically consisted of several non-contiguous parcels of territory of various sizes. Facing their lack of political power, the rulers of these petty states built up splendid monarchical households at their residences and pursued greater cultural achievements.

Duke John William, chafing under the loss, died in 1573, succeeded by his son Frederick William I. Upon his death in 1602 Saxe-Weimar was again divided among his younger brother John II and Frederick William's minor son John Philipp, who received the territory of Saxe-Altenburg. John's son Duke Johann Ernst I of Saxe-Weimar on occasion of the burial of his mother Dorothea Maria of Anhalt in 1617 established the literary Fruitbearing Society.

Thirty Years' War

[edit]At the outbreak of the Thirty Years' War, Duke Johann Ernst I supported the Protestant Bohemian estates under the "Winter King" Frederick V of the Palatinate, who were defeated at the 1620 Battle of White Mountain. Stripped of his title by Emperor Ferdinand II, he remained a fierce opponent of the Catholic Habsburg dynasty and died on Ernst von Mansfeld's Hungarian campaign in 1626.

His younger brother Wilhelm, regent since 1620, assumed the dignities upon his death. At first also an advocate of Protestant concerns, after the death of King Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden he chose to accord with the 1635 Peace of Prague that his Albertine cousins had negotiated with the emperor – against the opposition of his younger brother General Bernard of Saxe-Weimar, who entered into the French service under Cardinal Richelieu. Nevertheless, like many German estates, the Weimar lands were devastated by combat actions as well as by plague epidemics.

When in 1638 the Ernestine Saxe-Eisenach and Saxe-Coburg branch became extinct upon the death of Duke John Ernest, Wilhelm of Saxe-Weimar inherited large parts of his estates. In 1640 however he had to involve his younger brothers Ernest I and Albert IV, thereby (re-)establishing the Duchies of Saxe-Gotha and the short-lived Saxe-Eisenach, which was again dissolved upon Duke Albert's death in 1644.

Another rearrangement of the Ernestine lands took place in 1672 after Duke Frederick William III of Saxe-Altenburg, descendant of Duke John Phillip, had died without heirs and his cousin Duke Johann Ernst II of Saxe-Weimar inherited parts of his duchy, which originally had been split off the Saxe-Weimar territory in 1602. Johann Ernst II immediately divided the enlarged Saxe-Weimar lands between himself and his younger brothers John George I and Bernhard II, who received the Duchies of Saxe-Eisenach and Saxe-Jena, which reverted to Saxe-Weimar upon the death of Bernhard's son Duke Johann Wilhelm in 1690.

Weimar Classicism

[edit]

Upon the death of John George's descendant Wilhelm Heinrich in 1741, Duke Ernest Augustus I of Saxe-Weimar also inherited the Duchy of Saxe-Eisenach. He then ruled both duchies in personal union and decisively forwarded the development of his estates by the implementation of the primogeniture principle.

His son Ernest Augustus II, who succeeded him in 1748, died in 1758, whereafter Empress Maria Theresa appointed his young widow, Duchess Anna Amalia, regent of the country and guardian of her infant son, Charles Augustus.[1] The regency of the energetic Anna Amalia and the reign of Charles Augustus, who was raised by the writer Christoph Martin Wieland, formed a high point in the history of Saxe-Weimar.[1] Both dedicated patrons of literature and art, Anna Amalia and Charles Augustus attracted to their court the leading German scholars, including Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Friedrich Schiller and Johann Gottfried Herder, and made their residence in Weimar an important cultural center in an era referred to as Weimar Classicism.

In 1804, Duke Charles Augustus entered into European politics by marrying his son and heir Charles Frederick to Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna, sister of Emperor Alexander I of Russia. However, at the same time he joined Prussia in the War of the Fourth Coalition against the French Empire, and after the defeat at the Battle of Jena-Auerstedt, was forced to accede to the Napoleonic Confederation of the Rhine in 1806. In 1809, Saxe-Weimar and Saxe-Eisenach, which had been united only in the person of the duke, were formally merged into the Duchy of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach.

Dukes of Saxe-Weimar

[edit]- Johann Wilhelm (1554–73)

- Frederick William I (1573–1602), son of Johann Wilhelm

- Johann II (1602–05), brother

8 of his sons would co-govern the duchy

- Johann Ernest I (1605–20)

- Frederick (1605-1622)

- Wilhelm (1605–62)

- Albert (1606-40)

- Johann Frederick(1606-1628)

- Ernest (1606-1640)

- Frederick Wilhelm (1606-1619)

- Bernard (1606-1639)

- Johann Ernest II (1662–83), son of Wilhelm

- Wilhelm Ernest (1683–1728), son of Johann Ernest II

- Johann Ernest III (1683–1707), son of Johann Ernest II

- Ernest August I (1707–48), son of Johann Ernest III

- Ernest August II (1748–58), son of Ernest August I

- Karl August (1758–1809), son of Ernest August II

Merged with Saxe-Eisenach to form Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 24 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Saxe-Weimar, The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition, Columbia University Press (2001–2005), accessed December 22, 2005

External links

[edit]- German genealogies

- Genealogy of Dukes of Saxe-Weimar (in French)