Cameras for All-Sky Meteor Surveillance

| Cameras for All-Sky Meteor Surveillance (CAMS) | |

|---|---|

The CAMS station at Lick Observatory, in California, set up in April 2011. The CAMS box at the top contains the cameras. | |

| Mission statement | CAMS is an automated video surveillance of the night sky to validate the IAU Working List of Meteor Showers. |

| Commercial? | No |

| Location | Global |

| Founder | Peter Jenniskens |

| Established | October 10, 2010 |

| Funding | |

| Status | active |

| Website | www |

CAMS (the Cameras for All-Sky Meteor Surveillance project) is a NASA-sponsored international project that tracks and triangulates meteors during night-time video surveillance in order to map and monitor meteor showers. Data processing is housed at the Carl Sagan Center of the SETI Institute[1] in California, USA. Goal of CAMS is to validate the International Astronomical Union's Working List[2] of Meteor Showers, discover new meteor showers, and predict future meteor showers.

CAMS Methods

[edit]CAMS [3] networks around the world use an array of low-light video surveillance cameras to collect astrometric tracks and brightness profiles of meteors in the night sky. Triangulation of those tracks results in the meteor's direction and speed, from which the meteors’ orbit in space is calculated and the material's parent body can be identified.

The CAMS software modules, written by Peter S. Gural, have scaled up the video-based triangulation of meteors. The most widely used scripts to run these modules on PCs at the stations were written by Dave Samuels and Steve Rau. Through a series of computational and statistical algorithms, each streak of light in the video is identified and the track is verified as being a meteor or belonging to another light source like planes, or light reflected from moving clouds, birds, and bats.

The first CAMS camera stations were set up in October 2010 at Fremont Peak Observatory and in Mountain View, followed in April 2011 by a station at Lick Observatory, in California. A station in Foresthill was added to the CAMS California network in April 2015. CAMS has since expanded into 15 networks worldwide. Networks of cameras are located in the USA (California, Northern California, Arizona, Texas, Arkansas, Maryland, and Florida), in the BeNeLux (The Netherlands, Belgium and Germany), and in the United Arab Emirates on the northern hemisphere, and in New Zealand, Australia, South Africa, Namibia, Brazil, and Chile on the southern hemisphere.

CAMS Notable contributions

[edit]Demonstrate the presence of yet-to-be discovered long-period comets and improve their orbits

[edit]- In April 2021, CAMS published work that identified 14, and perhaps as many as 20, already known long-period comets as parent bodies of one of our meteor showers. Meteor showers were found for nearly all known comets approaching Earth orbit to 0.01 AU that have orbital periods in the 250 to 4,000 year range. Most long-period comet showers were found to be active for many days, showing precession of the comet orbit over time.[4]

- In April 2019, CAMS New Zealand station detected a brief outburst of 5 meteors from comet C/1907 G1 (Grigg-Mellish).[5] Based on the 1907 observations of the comet alone, valid orbit solutions showed a range of orbital periods but with a strong correlation between orbit node and orbital period due to an uncertain distance between comet and observer. The timing of the outburst was used to refine the node of the comet orbit, and thereby the orbital period.

Discovery of new meteor showers and validation of previously reported showers

[edit]On February 4, 2011, CAMS detected a brief meteor shower from a still undiscovered long-period comet, thereby proving the existence of that comet. The meteors radiated from the direction of the star Eta Draconis resulting in the new shower called the February Eta Draconids (FEDs)[6] This was just the first of a long list of newly discovered meteor showers. As of Feb 17, 2021, CAMS has helped establish [7] 92 out of 112 single showers [8] and recognized 323 out of 700 meteor showers in the Working List.

- 2021:

- CAMS networks in New Zealand and Chile detected a predicted outburst of meteors from comet 15P/Finlay on September 27–30, the first time meteors were seen from this comet and the new shower is called the "Arids" (number 1130). The outburst was caused by Earth crossing the 1995 dust ejecta

- CAMS Texas and CAMS California detected an outburst of Perseids. Peak rates increased to ZHR = 130 per hour above normal 40 per hour Perseid rates. The peak was at 8.2 h UTC August 14. Most meteors were faint. This encounter with the dust trails or Filament of 109P/Swift-Tuttle was not anticipated

- 2020:

- CAMS detected a new shower now called the gamma Piscis Austrinids[9]

- CAMS detected rho Phoenicids, a shower previously known only from radar observations.

- 2017:

- On December 13, CAMS captured 3003 Geminids and 1154 sporadic meteors which shattered all previous records on the number of meteors detected in a single night[10]

- 2011:

- CAMS detected the annual eta Eridanids (ERI) from comet C/1852 K1 (Charcornac)

- CAMS verified from video the April Rho Cygnids (ARC), originally discovered from radar by the Canadian Meteor Orbit Radar (CMOR)

Monitoring unusual activity of meteor showers

[edit]In recent years, the effort has shifted from mapping the annual meteor showers to monitoring unusual meteor shower activity.

| Meteor Shower Name | IAU Code | IAU Shower number | Year | Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arids | 1130 | 2021 | newly detected | |

| June theta2 Sagittariids[11] | 1129 | 2021 | newly detected | |

| gamma Crucids [12] | GCR | 1047 | 2021 | either newly detected or possible return of 1980 alpha Centaurids? |

| 29 Piscids[13] | PIS | 1046 | 2020 | newly detected; then stream showed once in October, then again in November |

| September upsilon Taurids[14] | SUT | 1045 | 2020 | newly detected shower |

| gamma Piscis Austrinids | 1036 | 2020 | newly detected | |

| sigma Phoenicids[15] | SPH | 1035 | 2020 | newly detected |

| chi Cygnids[16] | CCY | 757 | 2015 | newly detected and returned in 2020 |

| Volantids[17] | VOL | 758 | 2015 | newly detected as the New Year's Eve shower. Returned New Year's Eve 2020. |

- 2021:

- Detected a new shower in the June Aquilid Complex, the June theta2 Saggitarriids (IAU number 1129). The shower was also strong in 2020.

- Detected an unusual shower, the zeta Pavonids (IAU number 853). The shower activity profile had a full width at half maximum duration of only 0.46 degrees centered on 1.41 degree solar longitude.[18]

- Strong activity from the beta Tucanids (IAU number 108) detected, initially mistaken for the nearby delta Mensids (IAU 130), this shower was also strong in radar observations last year in 2020. A total of 29 beta Tucanids were triangulated by CAMS networks this year, compared to 5 meteors last year.[19]

- Detected a strong outburst of gamma Crucids (IAU number 1047) in February. This shower may have been a return of the 1980 alpha Centaurids outburst reported by visual meteor observers.

- 2020:

- A significant meteor activity from A-Carinids, an otherwise weak annual shower that was detected by CAMS[20]

- CAMS discovered meteors of chi Phoenicids, a new long-period comet[21]

- Outburst of Ursids caused by the 1076 A.D. dust of comet 8P/Tuttle[22][23]

- CAMS recognized early sightings of chi Cygnids in late August, forecasting the return of that shower. Shower was last seen in 2015. The shower indeed returned and was observed in detail in September.[24][25]

- 2019:

- CAMS detected an outburst of 15 Bootids, whose orbital elements resemble those of bright comet C/539 W1,[26][27] suggesting that this meteor shower was caused by the same bright comet as was described in Histories of the Wars, an 553 A.D. book. Expectation is that the comet is on its way back, and predictions were made on where to search in the sky based on the orbital elements of the meteoroid stream.

- CAMS captured an outburst of June epsilon Ophiuchids. The parent body was identified as periodic Jupiter Family comet 300P/Catalina[28]

- CAMS detected an outburst of Phoenicids from comet Blanpain.

- A predicted alpha Monocerotid outburst ("the unicorn shower") was observed by the CAMS Florida, but best viewing was over the Atlantic Ocean. Shower was wider and weaker than anticipated, which according to Jenniskens: "This suggests we crossed the dust trail further from the trail center than anticipated."[29]

- 2018:

- CAMS captured an outburst of October Draconids from 21P/Giacobini-Zinner.

- CAMS again detected the October Camelopardalids.

- 2017:

- Earth traveled through the 1-revolution dust trail of a long-period comet C/2015 D4 (Borisov). Jenniskens noted that "Only about once every 25 years is such an intermediate long-period comet discovered that passes close enough to Earth's orbit to have dust trail encounters. This one passed perihelion in 2014."[30] CAMS South Africa network captured 167 meteors.

- CAMS captured 12 meteors from an outburst of October Camelopardalids (OCT)[31]

- 2016:

- An outburst of gamma Draconids was detected by CAMS[32]

- CAMS picked up an outburst of Ursids in December.

- 2011:

- A mobile system of CAMS was used to observed an outburst of the 2011 Draconid meteor shower in Europe. First results from 28 Draconid trajectories and orbits show that the meteors originated from the 1900 dust ejecta of comet 21P/Giacobini-Zinner

Guiding astronomers in locating the site of freshly fallen meteorites

[edit]In 2016, Lowell Observatory CAMS in Arizona captured a -20 magnitude fireball from which 15 meteorites were recovered.[33] The results showed where LL type chondrites originate in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter.[34]

In 2012, the Novato meteorite that generated sonic booms was detected by CAMS,[35] and retrieved by local resident Lisa Webber following publication of tracking information. The meteorite was identified as a L6 type chondrite fragmental breccia.[36][37]

Visualization and data access

[edit]

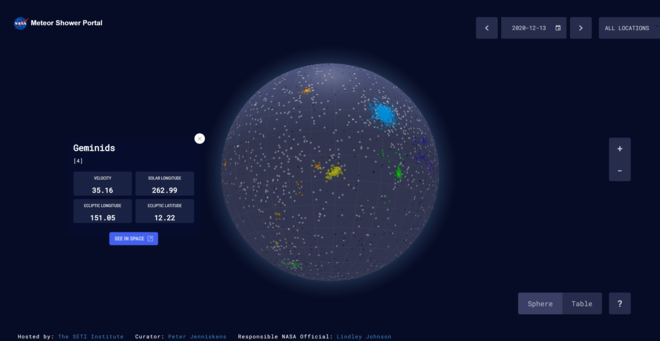

Every night, the combined CAMS networks generate a map of meteor shower activity. Those maps can be accessed the next morning at the CAMS online portal at cams

Building on top of these features, the online portal has been refined and upgraded by SpaceML[39] at meteorshowers

When clicking on one of the points in the websites above, the user is presented with a visualization of the CAMS-detected meteoroid streams in a solar system planetarium setting developed by Ian Webster. The site can be directly accessed at www

Featured in the media

[edit]- Asteroid 42981 Jenniskens is named after Dr. Peter Jenniskens

- The International Astronomical Union named main belt asteroids after CAMS team members Pete Gural [40] and Jim Albers [41] at the 2014 Asteroids, Comets, Meteors conference.

- The New York Times published a story on CAMS's meteoroid stream visualization tool[42]

- The Japanese broadcasting company NHK filmed the CAMS station at Lick Observatory for a documentary

- Nature News mentioned the impact of CAMS as "Eighty-six previously unknown have now joined the regular spectaculars, which include the Perseids, Leonids and Geminids."[43]

- Frontier Development Lab built an AI pipeline [44] and data visualization dashboard [45] for CAMS. This pipeline has been presented in the media by Nvidia blogs [46] and at their flagship conference, GPU Technology Conference.[47] The FDL collaboration on CAMS project, and the AI pipeline is an outcome of NASA's Asteroid Grand initiative,[48] under the purview of planetary defense,[49] when FDL was provided the mandate by NASA's Planetary Defense Co-ordination Office (PDCO) to organize the competition.[50] The CAMS AI pipeline is hosted on SpaceML.[51]

- Visualization developed from the CAMS data showing the Perseid meteor shower was chosen as the Astronomy Picture of the Day [52]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]![]() This article incorporates public domain material from "CAMS". Ames Research Center. NASA.

This article incorporates public domain material from "CAMS". Ames Research Center. NASA.

- ^ "Cameras for Allsky Meteor Surveillance (CAMS)". SETI Institute. Archived from the original on February 13, 2021. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ "IAU Meteor Data Center". www.ta3.sk. Archived from the original on March 9, 2021. Retrieved March 2, 2021.

- ^ Jenniskens, P.; Gural, P. S.; Dynneson, L.; Grigsby, B. J.; Newman, K. E.; Borden, M.; Koop, M.; Holman, D. (November 1, 2011). "CAMS: Cameras for Allsky Meteor Surveillance to establish minor meteor showers". Icarus. 216 (1): 40–61. Bibcode:2011Icar..216...40J. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2011.08.012. ISSN 0019-1035. Archived from the original on June 24, 2022. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ Jenniskens, Peter; Lauretta, Dante S.; Towner, Martin C.; Heathcote, Steve; Jehin, Emmanuel; Hanke, Toni; Cooper, Tim; Baggaley, Jack W.; Howell, J. Andreas; Johannink, Carl; Breukers, Martin; Odeh, Mohammad; Moskovitz, Nicholas; Juneau, Luke; Beck, Tim; De Cicco, Marcelo; Samuels, Dave; Rau, Steve; Albers, Jim; Gural, Peter S. (September 1, 2021). "Meteor showers from known long-period comets". Icarus. 365: 114469. Bibcode:2021Icar..36514469J. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2021.114469. ISSN 0019-1035. Archived from the original on May 26, 2021. Retrieved May 26, 2021.

- ^ "Southern Hemisphere Meteor Outburst". SETI Institute. SETI Institute. Archived from the original on December 6, 2022. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ Wall, Mike (July 27, 2011). "Evidence Found for Undiscovered Comet That May Threaten Earth". Space.com. Space.com. Archived from the original on February 14, 2021. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ Jenniskens, P.; Nénon, Q.; Albers, J.; Gural, P. S.; Haberman, B.; Holman, D.; Morales, R.; Grigsby, B. J.; Samuels, D.; Johannink, C. (March 1, 2016). "The established meteor showers as observed by CAMS". Icarus. 266: 331–354. Bibcode:2016Icar..266..331J. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2015.09.013. ISSN 0019-1035. Archived from the original on January 21, 2022. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ Jenniskens, P.; Nénon, Q.; Gural, P. S.; Albers, J.; Haberman, B.; Johnson, B.; Holman, D.; Morales, R.; Grigsby, B. J.; Samuels, D.; Johannink, C. (March 1, 2016). "CAMS confirmation of previously reported meteor showers". Icarus. 266: 355–370. Bibcode:2016Icar..266..355J. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2015.08.014. ISSN 0019-1035. Archived from the original on August 19, 2022. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ Lee, Angie (August 20, 2020). "CAMS System Discovers New Meteor Showers Using AI | NVIDIA Blog". The Official NVIDIA Blog. Archived from the original on December 20, 2020. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ "Cameras for Allsky Meteor Surveillance (CAMS)". cams.seti.org. Archived from the original on November 1, 2019. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ "NEW SHOWER DETECTED: JUNE THETA2 SAGITTARIIDS". Archived from the original on June 22, 2021.

- ^ "OUTBURST OF GAMMA CRUCIDS IN 2021 (GCR, IAU#1047)". meteornews. February 15, 2021. Archived from the original on February 21, 2021. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ "NOT SEEN BEFORE: SAME METEOROID STREAM SHOWS UP AGAIN A MONTH LATER". SETI Institute. Archived from the original on November 3, 2020. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ "The September upsilon Taurid meteor shower and possible previous detections". Meteor News. January 27, 2021. Archived from the original on February 20, 2021. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ Lee, Angie (August 20, 2020). "Starry, Starry Night: AI-Based Camera System Discovers Two New Meteor Showers". The Official NVIDIA Blog. Archived from the original on December 20, 2020. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ Jenniskens, P. (September 1, 2015). "New Chi Cygnids Meteor Shower". Central Bureau Electronic Telegrams. 4144: 1. Bibcode:2015CBET.4144....1J. Archived from the original on November 10, 2023. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ Jenniskens, P.; Baggaley, J.; Crumpton, I.; Aldous, P.; Gural, P. S.; Samuels, D.; Albers, J.; Soja, R. (April 1, 2016). "A surprise southern hemisphere meteor shower on New-Year's Eve 2015: the Volantids (IAU#758, VOL)". WGN, Journal of the International Meteor Organization. 44 (2): 35–41. Bibcode:2016JIMO...44...35J. ISSN 1016-3115. Archived from the original on September 12, 2021. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ "Narrow shower of zeta Pavonids (ZPA, #853)". Meteor News. March 29, 2021. Archived from the original on May 26, 2021. Retrieved May 26, 2021.

- ^ "Beta Tucanids (BTU #108) meteor outburst in 2021". Meteor News. March 18, 2021. Archived from the original on May 26, 2021. Retrieved May 26, 2021.

- ^ "Surprising A-Carinids Shower". SETI Institute. Archived from the original on December 6, 2022. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ "Newly Detected Chi Phoenicid Meteor Shower". SETI Institute. June 22, 2020. Archived from the original on December 8, 2022. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ "Ursids (URS#015) another outburst in 2020?". Meteor News. December 17, 2020. Archived from the original on February 18, 2021. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ "URSIDS METEORS 2016" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on February 15, 2020. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ "CAMS Networks detect possible return of Chi Cygnid meteor shower". SETI Institute. Archived from the original on December 6, 2022. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ "Possible upcoming return of the chi Cygnids in September 2020". Meteor News. August 27, 2020. Archived from the original on March 1, 2021. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ "OUTBURST OF 15-BOOTIDS METEOR SHOWER". Archived from the original on May 16, 2021. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ Jenniskens, Peter; Lyytinen, Esko; Johannink, Carl; Odeh, Mohammad; Moskovitz, Nicholas; Abbott, Timothy M. C. (February 1, 2020). "2019 outburst of 15-Bootids (IAU#923, FBO) and search strategy to find the potentially hazardous comet". Planetary and Space Science. 181: 104829. Bibcode:2020P&SS..18104829J. doi:10.1016/j.pss.2019.104829. ISSN 0032-0633. S2CID 213801936. Archived from the original on August 19, 2022. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ "JUNE EPSILON OPHIUCHID METEORS". Archived from the original on May 16, 2021. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ "alpha Monocerotids activity but no spectacular outburst". Meteor News. November 22, 2019. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ "Cameras for Allsky Meteor Surveillance (CAMS)". cams.seti.org. Archived from the original on November 1, 2019. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ "October Camelopardalids by CAMS". Meteor News. December 10, 2017. Archived from the original on March 4, 2021. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ Verbeeck, Cis. "Short and strong outburst of the gamma Draconids on July 27/28 | IMO". Archived from the original on March 9, 2021. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ "Arizona Fireball Update – Meteorite Found by ASU Team!". Arizona State University. Arizona State University. Archived from the original on June 24, 2019. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ "2016 Arizona Meteorite Fall Points Researchers to Source of LL Chondrites". SETI Institute. SETI Institute. Archived from the original on November 1, 2022. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ "Cameras for Allsky Meteor Surveillance (CAMS)". cams.seti.org. Archived from the original on March 24, 2021. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ "Novato Meteorite Consortium main page". asima.seti.org. Archived from the original on April 6, 2013. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ Hoover, Rachel (August 15, 2014). "NASA, Partners Reveal California Meteorite's Rough and Tumble Journey". NASA. Archived from the original on October 27, 2020. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ Ganju, Siddha; Koul, Anirudh; Lavin, Alexander; Veitch-Michaelis, Josh; Kasam, Meher; Parr, James (November 9, 2020). "Learnings from Frontier Development Lab and SpaceML -- AI Accelerators for NASA and ESA". arXiv:2011.04776 [astro-ph.IM].

- ^ Koul, Anirudh; Ganju, Siddha; Kasam, Meher; Parr, James (February 16, 2021). "SpaceML: Distributed Open-source Research with Citizen Scientists for the Advancement of Space Technology for NASA". COSPAR 2021 Workshop on Cloud Computing for Space Sciences. arXiv:2012.10610.

- ^ "JPL Small-Body Database Browser". ssd.jpl.nasa.gov. NASA. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ "JPL Small-Body Database Browser". ssd.jpl.nasa.gov. NASA. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ Fleur, Nicholas St (March 24, 2017). "Visualizing the Cosmic Streams That Spew Meteor Showers (Published 2017)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 19, 2021. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ Witze, Alexandra (September 17, 2015). "Newfound meteor showers expand astronomical calendar". Nature News. Vol. 525, no. 7569. Nature News. pp. 302–303. doi:10.1038/525302a. Archived from the original on September 2, 2016. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ Zoghbi, Susana; De Cicco, Marcelo; Stapper, Andres P.; Ordoñez, Antonio J.; Collison, Jack; Gural, Peter S.; Ganju, Siddha; Galache, Jose-Luis; Jenniskens, Peter (2017). "Searching for long-period comets with deep learning tools" (PDF): Deep Learning for Physical Science Workshop, NeurIPS. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 3, 2020. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ De Cicco, Marcelo; Zoghbi, Susana; Stapper, Andres P.; Ordoñez, Antonio J.; Collison, Jack; Gural, Peter S.; Ganju, Siddha; Galache, Jose-Luis; Jenniskens, Peter (January 1, 2018). "Artificial intelligence techniques for automating the CAMS processing pipeline to direct the search for long-period comets". Proceedings of the International Meteor Conference: 65–70. Bibcode:2018pimo.conf...65D. Archived from the original on November 10, 2023. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ Lee, Angie (August 20, 2020). "CAMS System Discovers New Meteor Showers Using AI | NVIDIA Blog". The Official NVIDIA Blog. Archived from the original on December 20, 2020. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ "Official Intro | GTC 2018 | I AM AI". YouTube. Archived from the original on April 12, 2021. Retrieved April 12, 2021.

- ^ Bonilla, Dennis (March 16, 2015). "Asteroid Grand Challenge". NASA. Archived from the original on January 14, 2021. Retrieved April 16, 2021.

- ^ Talbert, Tricia (December 21, 2015). "Planetary Defense". NASA. Archived from the original on April 17, 2021. Retrieved April 16, 2021.

- ^ Gustetic, Jennifer L.; Friedensen, Victoria; Kessler, Jason L.; Jackson, Shanessa; Parr, James (March 12, 2018). "NASA's Asteroid Grand Challenge: Strategy, Results and Lessons Learned". Space Policy. 44–45: 1–13. arXiv:1803.04564. Bibcode:2018SpPol..44....1G. doi:10.1016/j.spacepol.2018.02.003. S2CID 119454992.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on April 20, 2021. Retrieved April 20, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "APOD: 2018 August 8 - Animation: Perseid Meteor Shower". apod.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on April 19, 2021. Retrieved April 12, 2021.