Anarres

| Anarres | |

|---|---|

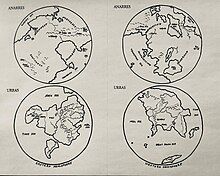

Anarres and Urras, as illustrated in The Dispossessed | |

| Created by | Ursula K. Le Guin |

| Genre | Science fiction |

| In-universe information | |

| Type | Planet |

| Race(s) | Anarresti, also known as Odonians |

| Location | Tau Ceti |

Anarres is a fictional planet in The Dispossessed, a 1974 novel by Ursula K. Le Guin. The work received both Hugo and Nebula awards and is regarded, along with The Left Hand of Darkness (1969), as one of Le Guin’s masterpieces, and a landmark in twentieth-century science fiction.[1]

Anarres is located, together with its neighbouring planet Urras, in the solar system of Tau Ceti, a real star at a distance of just under twelve light years from Earth (or Terra, as it is referred to in the novel).[2] Urras is the Old World: state-controlled, hierarchical, patriarchal, unequal but lush, materially rich and beautiful. Anarres is the New World: anarchist, communal, feminist, egalitarian, but arid and ecologically poor.

A century and a half before the novel opens, idealistic revolutionaries from Urras have gone into exile and settled Anarres. The dry satellite planet becomes the setting for a social experiment based on the principles of mutual aid, communalism and social equality.

On Anarres, the three great barriers to human freedom as identified by nineteenth-century anarchist thinkers – the state, organised religion and private property – are absent.[3] In the introduction to a 2017 collection of her Hainish novels and stories, Le Guin describes The Dispossessed as her attempt to write an "anarchist utopia".[4]

Plot and narrative structure

[edit]The Dispossessed tells the story of Shevek, a brilliant Anarresti physicist, who travels to Urras to advance his scientific research. Going against the "Terms of the Settlement" (and against the wishes of many on his home planet), Shevek wishes to re-establish contact between the "sister-worlds" of Urras and Anarres.[5]

The novel begins with Shevek’s departure from the Port of Anarres on board the space freighter Mindful. One plotline concerns his experiences in Urras, where he is feted as a visiting scientist at an eminent university in A-Io (one of three warring powers on this planet: the others are Thu and Benbili). The other narrative strand goes back in time to relate his upbringing and coming of age on Anarres: his education, relationships and his struggle to balance personal initiative with social responsibility.

Social, economic and political organisation

[edit]On Anarres, society is organised according to principles of mutual aid, voluntary association and absolute non-coercion. Economic activity is divided into syndicates and federatives, with work postings advertised via an automated system called Divlab: the administration of the division of labour.[6] The network of administration and management is called PDC: Production and Distribution Coordination. This (as Shevek explains to his hosts in Urras) is "a coordinating system for all syndicates, federatives and individuals who do productive work. They do not govern persons; they administrate production."[7]

Pravic, the rationally devised language of Anarres, makes no distinction between the concepts "work" and "play", but the term "kleggich" refers to drudgery: the kinds of menial or manual labour that most Anarresti volunteer for one day out of every decad (the ten-day cycle which forms the weekly unit on the planet).[8]

The portrayal of Anarres is drawn from the author’s wide research in social and political theory. Reflecting on what led her to write The Dispossessed, Le Guin remembered how the novel took shape in the aftermath of protests against the Vietnam War:

But, knowing only that I didn’t want to study war no more, I studied peace. I started by reading a whole mess of utopias and learning something about pacifism and Gandhi and nonviolent resistance. This led me to the nonviolent anarchist writers such as Peter Kropotkin and Paul Goodman. With them I felt a great, immediate affinity. They made sense to me in the way Lao Tzu did. They enabled me to think about war, peace, politics, how we govern one another and ourselves, the value of failure, and the strength of what is weak.

So, when I realised that nobody had yet written an anarchist utopia, I finally began to see what my book might be.[4]

Critical interpretations of Anarresti society

[edit]The social, economic and political organisation of Anarres is premised on ideas of decentralization found in the writings of anarchist thinkers ranging from Lao Tzu to Peter Kropotkin. The economic structure of Anarres is, in part, an application of Kropotkin's theory of anarcho-syndicalism, and Annaresti society follows a philosophical, as opposed to religious, version of Lao Tzu's Taoism.[9]

Anarcho-syndicalism on Anarres

[edit]According to Kropotkin's theory of anarcho-syndicalism, workers "enjoy their work, administer and organise themselves, and depend on other syndicates to help them to create a balanced society".[10] On Anarres, there is no government, and hence no police force or legal system. Work is produced by interdependent syndicates with workers supplied by Divlab, and the resulting produce is distributed by the PDC. This ensures the separation of the means of distribution from the means of production, akin to Kropotkin's emphasis on decentralization. [10] Hierarchy is ostensibly eliminated in the workplace and across Anarresti society as a whole. So, in contrast to a capitalist society like Urras, the motivation for labour on Anarres is not power, nor the pursuit of wealth accumulation and the ownership of property (concepts deemed reprehensible by Anarresti), but pleasure and service to community. Laia Asieo Odo, the founder of Anarresti political philosophy, stresses enjoyment and service to others in her writings which are circulated with near-religious reverence on Anarres:

A child free from the guilt of ownership and the burden of economic competition will grow up with the will to do what needs doing and the capacity for joy in doing it. It is useless work that darkens the heart. The delight of the nursing mother, of the scholar, of the successful hunter, of the good cook, of the skillful maker, of anyone doing needed work and doing it well—this durable joy is perhaps the deepest source of human affection, and of sociality as a whole.[11]

Kropotkin, Mutual Aid and non-coercion

[edit]There are many similarities between Le Guin’s Odo and Kropotkin, who argued that selfishness, aggressive competition and the survival of the fittest were the wrong conclusions to draw from Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution.[12] As a young man, Kropotkin travelled to Siberia to study geography, glaciers and animal behaviour, as well as the local peasant communities. What he saw there – the way animal communities cooperated and shared resources to survive in harsh conditions; the resilience and collective decision-making of village communes – led him to write Mutual Aid, which argues against theories of social Darwinism. Shevek echoes Kropotkin’s core argument at a cocktail party in Urras, when someone claims that the law of evolution is that the strongest survive. ‘Yes,’ Shevek replies, ‘and the strongest, in the existence of any social species, are those who are the most social. In human terms, most ethical.’[2]

Like his anarchist contemporary Mikhail Bakunin, Kropotkin argued (against Lenin and the Bolsheviks) that an authoritarian Party would never achieve a just society: a unity of ends and means is a key principle in anarchist thought.[13] Kropotkin’s anarcho-communism differed from Bakunin’s collectivism, however: it did not demand that an individual must work to access necessities like shelter, clothing, food.[3] On Anarres, these are freely provided – in communal domiciles, depositories, refectories – and any work or activity is to be undertaken voluntarily, without any explicit form of coercion. For those unwilling, there is the option to drop out of society and live as a nuchnibi, beyond the realm of the social conscience.

The perpetrators of more serious or violent anti-social behaviours on Anarres can request to be sent to the Asylum on Segvina Island, an insitution that is handled ambivalently within the novel. Some characters view it as a carceral institution or de facto prison; others describe it more as a therapeutic refuge: 'If there are murderers and chronic work-quitters there, it's because they asked to go there, where they're not under pressure, and safe from retribution.'[2]

Taoism and the Anarresti

[edit]Taoism, also known as Daoism, is a religious and philosophical system which emerged in ancient China.[14] Le Guin translated a seminal work of Taoist philosophy, Tao Te Ching, which is said to have been written by the ancient Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu (also called Laozi)[15] [16] It is here and elsewhere in her reading of Lao Tzu, that Le Guin was exposed to Taoist thought. To attempt a singular definition of Taoism is a controversial feat, as Chad Hansen has discovered. [14] However, Douglas Barbour has noted that the imagery of light intertwining with dark which permeates the stories set in Le Guin's Hainish universe, and the vision they espouse of balance as a way of life, draw on the central tenets of Taoist thought: balance and paradox.[17] Balance is similarly key to the utopian way of life on Anarres, with each individual, and the syndicate for which they work, held to be serving an essential purpose which keeps society functional. Le Guin uses a bodily analogy to illustrate this system. Odo's text, which provides the foundational philosophy for Anarresti way of life, is titled The Social Organism.[18] As the Anarresti practise Odo's philosophy, each individual in society is likened to an element at the cellular or organic level in the Anarresti social body.

Shevek sees his quest to re-establish relations with the planet Urras, despite the societal dogma prohibiting this, as his function in the social organism: to remind the Anarresti society, which had grown bureaucratic, of its anarchist origins. As he puts it, "It was our purpose all along—our Syndicate, this journey of mine—to shake up things, to stir up, to break some habits, to make people ask questions. To behave like anarchists!"[19]

Geography, environment and ecology

[edit]Anarres has one continuous landmass and three main oceans (the Sorruba Sea, the Temaenian Sea, the Keran Sea).[2] The seas have not been connected for several million years, and so their life forms have followed insular courses of evolution, with a diverse range of fish and other marine organisms.

On land, however, there are few endemic species and 'only three phyla, all non-chordates – if you don't count man'.[2] Organic evolution on Annarres has produced no insects, birds, quadrupeds or flowering plants. The planet’s climate since human settlement has been shaped by a millennial era of dust and dryness. The long beaches of the Southeast region are fertile, supporting fishing and farming communities, but beyond the arable coastal strip are the dry plains of the Southwest: an expanse that is largely uninhabited (except for a few isolated mining towns) and known colloquially as the Dust.[20] 'Nowhere in the geography of utopia,' wrote one reviewer of The Dispossessed, 'is there an island so fundamentally hostile to human flourishing.'[21]

Flora on Anarres are mainly spiny scrub or semi-desert species like moonthorn. The dominant plant genus is the holum tree, used to make food, textiles and paper. Old World grains and fruit trees have been imported from Urras but grow only in the higher-rainfall regions of Abbenay and the Keran Sea. In terms of terrestrial fauna there are only bacteria (many of them lithophagous) and a few hundred species of worm and crustacean on Anarres.[2]

The Annaresti engage in large-scale projects of tree-planting to redress the aridity and increase the fertility of their world. The 'afforestation of the West Temaenian Littoral' (the west coast of the Temaenian Sea) is described as one of the great undertakings of the fifteenth decade of the Settlement on Anarres, 'employing nearly eighteen thousand people over a period of two years.'[2] At the Northsetting Regional Institute, biologists and fish geneticists (like Shevek's partner Takver) study techniques to increase and improve the edible fish stocks in the three oceans of Anarres.[2]

Man fitted himself with care and risk into this narrow ecology. If he fished, but not too greedily, and if he cultivated, using mainly organic wastes for fertilizer, he could fit in. But he could not fit anybody else in. There was no grass for herbivores. There were no herbivores for carnivores. There were no insects to fecundate flowering plants; the imported fruit trees were all hand-fertilized. No animals were introduced from Urras to imperil the delicate balance of life, only the settlers came, and so well scrubbed internally and externally that they brought a minimum of their personal fauna and flora with them. Not even the flea had made it to Anarres.[22]

The history of settlement

[edit]Anarres was settled by the Odonians some 170 years prior to Shevek’s visit to Urras in The Dispossessed.[23] Before then, Urrasti astronomer-priests had admired Anarres from a distance, taking special notice of the region that would later become the Annares town of Abbenay for its greenness. They called it Ans Ho, "the Garden of Mind: the Eden of Anarres".[24] When Urrasti ships later arrived on Anarres, the climate in Ans Ho proved inhospitable, but it was discovered to be rich in the minerals that were scarce on Urras owing to over-extraction in the Urrasti ninth and tenth millenia. As such, an Urrasti mercury mining settlement was founded in Ans Ho near the Nera The mountains. It was re-named Anarres Town but, the narrator cautions: "It was not a town, there were no women. Men signed on for two or three years’ duty as miners or technicians, then went home to the real world."[25]

Anarres was then under the rule of the Urrasti Council of World Governments. However, a group of gold miners from the nation of Thu, unbeknownst to the Council of World Governments, lived permanently in secret in the Eastern hemisphere of Anarres with their wives and children.[25] When the government of Thu collapsed, and rebellion by the International Society of Odonians began to threaten governance on Urras, the Council of World Governments gave Anarres to the Odonians in an attempt to appease them.[25] So, about two hundred years after their first ship had landed on Anarres, the Urrasti evacuated the planet, leaving behind a few Thu gold-miners who had chosen to remain. Over the course of twenty years, one million Odonian settlers migrated to begin life anew on Anarres.[25]

Relations between Urras and Anarres

[edit]Ships from Urras arrive in the Port of Anarres, near the city of Abbenay, eight times each year. [26] They bring fossil oils, petroleum, new species of fruit or grain, and electronic equipment and machinery that the Annarresti cannot manufacture for themselves, in exchange for mercury, copper, aluminum, uranium, tin, and gold. [26] This is known as the Trade Agreement.

According to the Terms of the Closure of the Settlement, nobody from the ships is allowed beyond the wall of the Port of Abbenay.[27]

Main communities and features

[edit]Formerly known as both Ans Ho and Anarres Town, the first Odonian settlement that was established on Anarres is Abbenay, meaning Mind in the Odonian language.[28] In theory, in accordance with Odo's vision, communities on Anarres are to be self-reliant but connected by networks of transport and communication to allow for the free-flow of ideas and goods. This would allow for exchange without social hierarchy: "There was to be no controlling center, no capital, no establishment for the self-perpetuating machinery of bureaucracy and the dominance drive of individuals seeking to become captains, bosses, chiefs of state."[28] However, Odo's theory of decentralization was developed with the ecologically-rich Urras as a model. On Anarres, resources are scarce and scattered widely across the planet, rendering self-sufficiency impossible for some communities. So, despite Odo's initial intentions, Abbenay has come to be the center of Odonian society. Administration technology, the division of labour, the distribution of goods, and the federatives of the syndicates are all here.[29] The only space port in Anarres is also here, allowing for trade with Urras.

Communities on Anarres all follow the same basic structure, consisting of "workshops, factories, domiciles, dormitories, learning centers, meeting halls, distributories, depots, refectories."[30] In Abbenay, buildings dedicated to similar industries cluster together around open squares "giving the city a basic cellular structure: it was one subcommunity or neighborhood after another."[30]

Abbenay was poisonless: a bare city, bright, the colours light and hard, the air pure. It was quiet. You could see it all, laid out as plain as spilt salt.[2]

Notes

[edit]- ^ "sfadb : Ursula K. Le Guin Awards". www.sfadb.com. Retrieved 2024-06-07.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Le Guin, Ursula K. (1974). The Dispossessed. New York: Harper Voyager.

- ^ a b Jaeckle, Daniel P. (2009). "Embodied Anarchy in Ursula K. Le Guin's The Dispossessed". Utopian Studies. 20 (1): 75–95 (p.75). doi:10.2307/20719930. ISSN 1045-991X. JSTOR 20719930.

- ^ a b Le Guin, Ursula K. (2017-08-30). ""Introduction" from Ursula K. Le Guin: The Hainish Novels & Stories, Volume One". Reactor. Retrieved 2024-03-25.

- ^ Le Guin, Ursula K. (1974). The Dispossessed. New York: Harper Voyager. p. 336.

- ^ Le Guin, Ursula K. The Dispossessed. p. 149.

- ^ Le Guin, Ursula K. The Dispossessed. p. 76.

- ^ Le Guin, Ursula K. The Dispossessed. p. 92.

- ^ Jones, Hilary A. 'Balancing Flux and Stability: Ursula K. Le Guin's The Dispossessed' (unpublished doctoral dissertation, Pennsylvania State University, 2011).

- ^ a b Jones, Hilary A. Balancing Flux and Stability: Ursula K. Le Guin's The Dispossessed.' p.iv.

- ^ Le Guin, Ursula K. The Dispossessed. p. 247.

- ^ Kropotkin, Peter (1902). Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution. New York: McClure Phillips & Co.

- ^ Fiala, Andrew (2021), Zalta, Edward N. (ed.), "Anarchism", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2021 ed.), Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, retrieved 2024-11-29

- ^ a b Hansen, Chad (2003-02-19). "Daoism". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 2024-06-06.

- ^ Ellwood, Robert S.; Alles, Gregory D., eds. (2007). The Encyclopedia of World Religions (Revised ed.). New York: Facts on File. p. 262.

- ^ Tzu, Lao (1997). Tao Te Ching: A Book About the Way and the Power of the Way. Translated by Le Guin, Ursula K.; Seaton, Jerome P. Shambhala.

- ^ Barbour, Douglas (1974). "Wholeness and Balance in the Hainish Novels of Ursula K. Le Guin". Science Fiction Studies. 1 (3): 164–173 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Le Guin, Ursula K. The Dispossessed. p. 101.

- ^ Le Guin, Ursula K. The Dispossessed. p. 384.

- ^ Le Guin, Ursula K. The Dispossessed. p. 46.

- ^ Bierman, Judah (1975). "'Ambiguity in Utopia: The Dispossessed'". Science Fiction Studies. 2 (3) – via EBSCO.

- ^ Le Guin, Ursula K. The Dispossessed. p. 186.

- ^ Le Guin, Ursula. The Dispossessed. p. 346.

- ^ Le Guin, Ursula. The Dispossessed. p. 93.

- ^ a b c d Le Guin, Ursula K. The Dispossessed. p. 94.

- ^ a b Le Guin, Ursula K. The Dispossessed. p. 92.

- ^ Le Guin, Ursula K. The Dispossessed. p. 357.

- ^ a b Le Guin, Ursula K. The Dispossessed. p. 95.

- ^ Le Guin, Ursula K. The Dispossessed. p. 96.

- ^ a b Le Guin, Ursula. The Dispossessed. p. 97.

Works Cited

[edit]- Barbour, Douglas (1974). "Wholeness and Balance in the Hainish Novels of Ursula K. Le Guin". Science Fiction Studies. 1 (3): 164–173 – via JSTOR.

- Ellwood, Robert S.; Alles, Gregory D., eds. (2007). The Encyclopedia of World Religions (Revised ed.). New York: Facts on File.

- Hansen, Chad (2003-02-19). "Daoism". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 2024-06-06.

- Jaeckle, Daniel P. (2009). "Embodied Anarchy in Ursula K. Le Guin's The Dispossessed". Utopian Studies. 20 (1): 75–95. doi:10.2307/20719930. ISSN 1045-991X. JSTOR 20719930.

- Jones, Hilary A., 'Balancing Flux and Stability: Ursula K. Le Guin's The Dispossessed' (unpublished doctoral dissertation, Pennsylvania State University, 2011)

- Le Guin, Ursula K. (2017-08-30). ""Introduction" from Ursula K. Le Guin: The Hainish Novels & Stories, Volume One". Reactor. Retrieved 2024-03-25.

- Le Guin, Ursula K. (1974). The Dispossessed. New York: Harper Voyager.

- Science Fiction Awards Database (sfadb), "Ursula K. Le Guin Awards," Locus Science Fiction Foundation, last updated 22 Feb 2022, http://www.sfadb.com/Ursula_K_Le_Guin [accessed 6 June 2024]

- Tzu, Lao (1997). Tao Te Ching: A Book About the Way and the Power of the Way. Translated by Le Guin, Ursula K.; Seaton, Jerome P. Shambhala.