Lakes in Bengaluru

Lakes and tanks in the metropolitan area of Greater Bangalore and the district of Bangalore Urban are reservoirs of varying sizes constructed over a number of centuries by various empires and dynasties for rainwater harvesting. Historically, these reservoirs were primarily either irrigation tanks or for the water supply, with secondary uses such as bathing and washing. The need for creating and sustaining these man-made dammed freshwater reservoirs was created by the absence of a major river nearby coupled with a growing settlement. As Bangalore grew from a small settlement into a city, both of the primary historical uses of the tanks changed. Agricultural land witnessed urbanization and alternate sources of water were provisioned, such as through borewells, piped reservoir water and later river water from further away.

The topography of the three main gentle natural valley systems allowed for the creation of interconnected tanks and wetlands where water flows downstream through a series of channels or drains. These tank cascades or chains have seen accelerated change and fragmentation caused by urbanisation in the past four decades.[1] Some lakes have been redefined as recreational spaces. Some have been built upon. Other lakes have reduced in size and are in various stages of deterioration. While associated pollution is rampant such as the case of Bellandur Lake which is used as a sewage tank, numerous public and private efforts have been undertaken to address sewage treatment, prevention of dumping and encroachment.

Terminology

[edit]Lakes are called keres (ಕೆರೆ) in Kannada language,[2] and are traditionally referred to as tanks.[3] Researcher Rohan D'Souza has suggested that the concept of 'kere' and 'lake' differ; for example the former also refers to the wetland and bund while the latter focuses more on a body of water surrounded by land.[4] When the forest department started to have a larger role in the administration of these waterbodies in the 1980s the word 'lake' started to be used as compared to 'kere' or 'tank'.[3][5] In accordance with this terminology, communication and practices related to these waterbodies were impacted.[3] Anthropologist Smriti Srinivas writes that tank is also a simplification that incorporates both natural and manmade waterbodies into its context since identification of bodies of water in the region that were historically natural is a task.[6] A 1986 report classifies some tanks as 'disused' tanks.[7]

There is no specific definition for what a lake is in India.[8][9] Urban lakes also have no specific definition.[10] In Bangalore, smaller waterbodies 1-3 acre in size are called gokattes and waterbodies less than 1 acre are called kuntes.[11] The words kere and katte go back to usage by the Hoysala's.[12] Kaluves can be translated as canals,[13] while in the context of Bangalore rajakaluves refer to bigger or large canals, channels or drains, specifically storm water drains, that connect the lake cascades.[14][15] Kalyanis refer to square tanks used for immersion (see temple tanks).[16][17] Other bodies of water include a well, 'bhavi', and pond for domestic use, 'kola'.[17]

History

[edit]Rainwater has been stored in reservoirs or irrigation tanks in the Indian subcontinent for many centuries.[18] In Bangalore and the surrounding regions of Mysore these tanks numbered in the thousands and varied in size according to the rains.[18] They were made primarily for the purposes of irrigation and drinking water, and secondary uses such as fishing, washing and other domestic needs.[19][20] Inscriptions provide some insight into their history.[21] The history and creation of the reservoirs is linked to different empires, dynasties and periods of the British Raj.[22] The Ganga and Chola dynasty, the Hoysala Empire, the Vijayanagara Empire, Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan and the Wadiyar dynasty are all associated tanks in Bangalore, including their creation, maintenance and use.[22] These tanks or lakes along with open water wells constituted the water supply infrastructure.[23] Socio-economic factors, population distribution, caste, and wealth affected interaction with water bodies.[24] The neerganti were organised labour traditionally associated with regulating irrigation water.[25][26] Voddas were the tank builders.[27] The traditional well diggers are the Manu Waddar.[28][29] The Vanniyakula Kshtriya or Thigala were horticulturists associated with lakes such as Sampangi.[30] They brought the Karaga celebration to Bangalore.[30][31] The roles of these communities have been diluted over time.[32] Cultural and religious associations abound.[33] Urbanisation has had diverse but mixed influence on these communities.[34] It is often the case that when the history of these tanks is discussed it is idealized.[20][35]

The dependence on tanks and other sources of water such as wells reduced with the implementation of schemes that brought water from Hesaraghatta Lake in 1894, T G Halli Reservoir in 1933, and Cauvery River from the 1970s.[35][36] Borewells also reduced dependence on reservoirs.[37] The Dharmambudhi Tank is used as an example to portray historical change,[38] and change of a commons in Bangalore over the centuries.[39] The tank goes back to at least the 16th century; some historical references point to a much earlier reservoir at the same location.[40][41] The lake would be used until the end of the 19th century after which is saw unchecked decay as a waterbody.[42] However its lakebed was located in prime area and continued to be used for various events, festivals, and gatherings.[42][43] Part of the lakebed was still wetland and had wells.[39] In the 1960s a portion of the lakebed was set aside for the construction of a bus stand.[44] Of the many channels and lakes that were connected to Dharmabudhi in the past such as the former Sampangi Lake, Kempambudhi Lake and Sankey Tank remain.[43]

Sampangi lake supported both the Pete and cantonment. It provided irrigation for millet and paddy cultivation. Construction in the area included a park in 1879, a hospital in 1886 and a school in 1898.[30] Around 1895 the lake stopped being used officially as a water source and inflow channels severed.[30] There were contesting claims as to how the lake and lakebed should be used. By 1935 all that remained was a small square tank. On the lakebed several constructions followed.[30] An eponymously named stadium was constructed on a portion of Sampangi lake in 1946, now known as the Sree Kanteerava Stadium. This was followed by an increase in surrounding built up area. In 1995, another portion of the former wetland was used to build the Kanteerava Indoor Stadium.[30]

Lakes or tanks, including dry ones, have been converted to commercial areas, industries, government buildings, bus stands, sports facilities, playgrounds and residential colonies, a few tanks were breached under a malaria eradication programme.[45][46] When Bangalore Golf Course was formed in 1876, it was located in the center of the city, and then land was relatively easily obtained.[47] In 1973 the Karnataka Golf Association was formed and the members started looking for a location to set up a golf course. Among the several locations Challaghatta lake or tank was suggested, then located on the outskirts of the city.[47] At the time there were ample lakes in the city and not much fuss was made related to the lake itself.[48] After a number of administrative processes involving multiple departments of the local administration and multiple Chief Ministers, and conversion of the area into a golf course designed by an Australian architectural firm, the first 9 holes were inaugurated in 1986. Multiple national and international golf tournaments have been held at the course.[49]

In 1986 the Lakshman Rau committee (under a retired administrative officer; see N. Madhava Rao)[relevant? – discuss] came out with a report highlighting the failure to maintain various tanks and made comments covering lake boundaries, water quality, the construction of tree parks in areas breached, to monitoring and conducting further study for new tanks.[50][51] The committee identified 127 lakes and transferred 90 to the forest department.[52] Since the 1980s custody of the lakes in the city has seen numerous changes.[53][54] The former Lake Development Authority experimented with public–private participation which included leasing out of four lakes.[55] Government administration of the lakes in the city mainly fall under a few urban local and state regulatory bodies.[56][57] Outside the city management is under the village and district Panchayats, and the Minor Irrigations department depending on the size of the lake.[5] Others forms of participation in the form of corporate social responsibility, general public involvement, including coordination with government efforts, and formation of lake groups, has resulted in some lakes seeing successful attempts at conservation and rejuvenation.[58][59] There are numerous measures undertaken, debated and contested by stakeholders in relation to the rejuvenation (restoration, revival, rehabilitation, conservation) of lakes. [60] Failure of these processes has been observed.[61] Urbanization has impacted the lakes in various ways, some lakes have completely disappeared, others have been reduced to pools, some have been encroached upon, some are in various stages of deterioration, some have dried up, and some have been leased.[62] The Koliwad committee, set up by the Karnataka legislature in 2014,[63][64] reported thousands of acres of encroachment of lake land.[65]

Topography and hydrology

[edit]

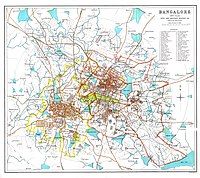

The topographic setting of the city has radial slopes towards east and west with a smooth ridge running north to south; rainfall over the ridge area gets divided and flows east or west into the three gentle slopes and valleys of Koramangala–Challagatta, Hebbal and Vrishabavathi. The average elevation is roughly 900 m (2,952.8 ft). These naturally undulating terrain of hills and valleys lends itself to the development of tanks that can capture and store rainwater. Small streams are formed by each valley starting with the ridge at the top. A series of shallow tanks varying in size are developed by the construction of bunds.[66][67] A tank generally consists of a shallow inflow area and a relatively deeper outflow area where the bund is.[68] The tank can further be zoned into a flooded area and a waterlogged zone.[69] Monsoons recharge the tanks and the outflow can be regulated for irrigation of monsoon crops during the last six months of the year. Most tanks are dry a couple of months before the onset of the new monsoon. A second crop can be considered on the basis of water levels. Other seasonal changes affect the water level. Urban sewage inflow allows some lakes to retain their water spread for a longer period.[70] Initially serving as a water source, these tanks over time also developed features of closed water lentic ecosystem habitats.[71] The catchments on the east and west of the ridge belong to the Ponnaiyar River and Arkavathi River respectively. Both these rivers flow into the Kaveri.[72]

The tank-canal linkages or rajakaluves (large canals or stormwater canals) were redefined by the colonial administration once they became the location for the sewerage network.[15] Rajakaluves now refer to both the inter-lake linkages and the sewerage, and are translated as stormwater drains.[15] In the 21st century there are 842 km in the drain network.[73] Urbanisation has impacted these.[74][75] Ensuring adequate water flow and no blockages is undertaken by the local administration.[76] Encroachment of storm drains and catchment areas can cause both drying up and flooding of lakes.[77] These drains often carry sewage in it, which results in the lakes getting polluted.[78]

Bangalore has a mean annual rainfall of 859.6 mm (2.8 ft) with June to September seeing the majority of rainfall.[67][66][79] 2022 was the wettest year with over 1700mm of rainfall.[80][81] The city sees around 60 rainy days a year.[82] The minimum rainfall is 587.8 mm/year.[79] An estimate of the rain water potential is 45000 million litres.[79] The annual mean temperature is 24 °C (75.2 °F) with extremes ranging from 37 °C (98.6 °F) to 15 °C (59.0 °F).[36] The highest and lowest temperature ever recorded in Bangalore has been 38.9 °C and 7.8 °C. in 1931 and 1884 respectively.[83]

Quantity

[edit]

There are various boundaries and methods that have been considered when counting lakes or tanks.[85] This includes the different jurisdictions of concerned government bodies such as BBMP, BDA, BMRDA; the different limits of Bangalore Metropolitan Area, Greater Bangalore, Bangalore Rural district, Bangalore Urban district; and counts mentioned in reports such as the N Lakshman Rao report of 1986.[86] Over time, the expansion of the limits of the city has resulted in a transfer of lakes in the rural district to the urban district.[87]

Bangalore has grown in area from 69 km2 (17,000 acres) in 1949 to over 700 km2 (170,000 acres) by 2007.[88][89][82] The area covered by water bodies in Greater Bangalore and Bangalore Urban has seen a sharp decline since the 1960s and 1970s.[90][91][92] Greater Bangalore has seen a reduction in water cover from 20.8 km2 in 1965 to 12.5 km2 in 2018.[91] A study published in 2008 found that in the heart of the city only 17 good lakes exist as against 51 healthy lakes in 1985.[90] A 2020 report listed 211 lakes within BBMP boundary limits.[93] There are six cascading lake series- Varthur, Puttenahalli, Hulimavu, Byramangala, Yellamallappa Chetty and Madavara.[89]

In 2015, a survey of all lakes in Bangalore Urban totaling 834 was completed.[94] BMRDA in 2001 identified 2789 lakes (2-50 hectares in size) within its limits.[95][96] In 2013, the jurisdiction of the minor irrigation department, BMRDA and BDA was 3578, 2789 and 596 tanks/lakes respectively.[97] The Koliwad committee (2014-2016) listed 1545 lakes.[63] A 2018 study by an autonomous institute under the Karnataka government counted 1521 water bodies in the Bangalore Metropolitan Area, out of which 837 were disused.[11]

Quality

[edit]The largest lake in the city Bellandur Lake is "severely polluted".[98] The lake receives 520 million litres per day of sewage and other waste that amounts to about 40% of the city's total.[98] Out of this roughly half is treated and diverted for irrigation. Otherwise the only inflow is rainwater.[98] When aquatic systems around the world are taken into consideration, Bellandur Lake has methane emissions that are among the highest in the world.[98] The lake has been in the news for its pollution, froth, and fire.[99] Post-2015 deliberations with regard to what the end-goal of a rejuvenation of Bellandur lake would entail were held.[20] The cause of the water quality situation in the lake was discussed.[20] No simple solutions were found.[20] Heavy metal contamination in Bellandur Lake impacts concentration of heavy metals in the soil and crop in areas irrigated using untreated lake water.[100] Despite the numerous shortcomings presented by Bellandur and downstream Varthur lakes, these aren't representative of the many more shortcomings of water management in the rest of Bangalore.[101] Byramangala Lake has also seen froth.[102][103] A number of factors impact measurements and interpretation of water quality and pollution.[104][105][further explanation needed]

India's National Water Quality Monitoring Programme is implemented in Bangalore by the Karnataka State Pollution Control Board through a network of over 100 monitoring stations located at lakes and tanks.[106] Monthly monitoring data is classified under pre-defined water quality criteria A-E.[106] In 2022, according to this data water in all the lakes in Bangalore were undrinkable with no lake falling under categories A-C.[107]

Water hyacinth, and other macrophytes and phytoplankton, are bioindicators of certain characteristics of water quality. Using satellite imagery between 1988 and 2019 (see #Ecology) significant areas of these have been observed covering various lakes in Bangalore, varying in coverage of the wetland according to lake, season and other factors.[108][37] There have been occurrences of mass fish mortality.[109][110][111][112] Immersion of Ganesha idols that are made with specific types of material has impacted water quality.[113][114] Some types of painted idol immersion has had significant effects on aquatic life.[115] Over 150,000 idols were submerged in 2022.[116] Measures to minimize pollution during the festival include use of earthen idols and smaller disconnected artificial tanks.[116]

Integrated wetlands, constructed wetlands, and floating wetlands have been utilized to improve water quality.[117][118] The integrated wetland of Jakkur Lake consists of partially treating sewage inflow before entry into a constructed wetland adjacent to the main lake body.[117] A 10 MLD treatment plant utilizes UASB technology and extended aeration.[117] This is followed by a constructed wetland spread over about 11 acres consisting of shallow followed by deeper settling basins with a variety of aquatic plants.[117] The constructed wetland at Agara Lake is spread over 9 acres.[119] Floating wetlands have been used at multiple lakes with varying success, notably Hebbagodi Lake.[118][120] Some lakes have wastewater treatment plants with direct inflow into the main lake area.[118]

Urban flooding has been considered as a disaster by National Disaster Management Authority following major flooding events in cities in India in the 2000s including Bangalore.[121][122] While there are similarities between cities in the causes of the floods, Bangalore has some unique exacerbating features with regard to its lake ecosystem.[121]

Ecology

[edit]Birds

[edit]The Birdwatchers' Field Club of Bangalore released their first list of birds in Bangalore in the 1970s. The revised list of 1994 also contains recorded sightings such as that of little grebe at Ulsoor tank in 1930 and data from the waterfowl census conducted since 1987.[123] The 1994 list records over 220 regularly sighted birds.[123] 109 birds are wetland birds and additional 30 species are favoured by the presence of water.[123] A study conducted by the same group in 1989 observed economic activities in and around the tanks which affected their ecology. Out of 97 tanks that were observed in a radius of 30 km, unregulated mudlifting and brickmaking were practiced in a large number of the lakes.[124] Micro-habitats for aquatic birds in Bangalore can be grouped into roughly five categories: open water birds, waders and shoreline birds, meadow and grassland birds, birds of reedbeds and other vegetation, birds of open airspace above wetlands.[125] Some birds frequent multiple micro-habitats. The ninth and tenth edition of the census of wetland and water birds in 1995 and 1996 conducted by the Birdwatchers' Field Club in coordination with the state forest department found 29 lakes which had twenty or more species such as Hebbal, Hosakote and Kalkere.[125] 25 lakes were found with over 500 birds.[125] The pond heron was found to be the most prevalent species among all the lakes, however no one species was present in all the lakes. Common waders include egret, sandpiper and brahminy kite.[125] Kingfisher was the most common open water bird.[125] The most common duck was Garganey.[125] Pintail and Coot were common reed and other vegetation birds.[125]

A study using eBird data from 2014 to 2019 from 44 lakes in the city had a sample size that included a total of 263 species.[126] In this study, the area of the lake and its position in the city impacted bird richness.[126] Most resident species saw an increase while most migratory species decreased.[126] An earlier study of 15 lakes in the city identified birds such as kingfishers, purple moorhen, little grebes, darter, purple heron, grey herons and pond herons.[127] A 2005-2007 study observed 112 bird species at seven lakes; Hebbal Lake had 74 species while Yediur Lake had 15 species.[128] Another localised study of aquatic birds found that the two of the most abundant species are Anas querquedula, a species of duck, and Bubulcus ibis, a species of heron.[129] Bird poaching and hunting was rampant in 1989.[130] It now occurs to a much lesser extent.[131]

Fish

[edit]

20 types of fish have been observed in the lakes.[132] Cyprinidae family is dominant.[132] Fish diversity and bird biodiversity are impacted by fishing practices.[133][134][135] Appropriate water bodies are leased out for fishing purposes.[136] Fishes bred for food include carps such as catla, labeo, mrigal, and other types such as tilapia, catfish. Labeo rohita or rohu is the most commonly bred fish.[136] In 2021 Jakkur Lake supported a number of fishing families.[137] The lake provides up to 200 kg of fish per day.[138] The catch can go up to 500 kg.[137] There is a fish farm and research center beside Hebbal Lake.[136]

Macrophytes

[edit]Imagery from the Indian Remote Sensing Programme for the years 1988-2001 were used to assess growth of water hyacinth in six lakes in Bangalore.[108] Among the largest areas in this study under water hyacinth was observed in Hebbal Lake at 20 ha (49 acres) out of a total water spread of 30 ha (74 acres).[108] Nagavara Lake had the highest ratio of water hyacinth to water spread; in March 1989 the lake was completely covered.[108] In the mid-1980s Neochetina eichhorniae, used in the biocontrol of water hyacinth, was released on an experimental basis in a specific area of Bellandur Lake.[139] An impact on water hyacinth was observed. The insect had also been recorded in the coming months in downstream Varthur Lake signifying a capability to migrate.[139] Within a few months infestation of all water hyacinth in Varthur Lake was observed.[139]

Analysis of freely available Google Earth imagery between 2002 and 2019 for macrophytes and phytoplankton cover in Bellandur and Varthur lakes showed that macrophyte cover never fell below 29% of the total wetland cover with a perennial average of nearly 60%. Algae was about half that of the macrophyte cover.[37] Water hyacinth has favoured types of moorhen, heron, and egret, and has caused the loss of a type of wader.[123] Aquatic weed harvesters are used on Bellandur lake.[140]

Common emergent aquatic plants include alligator weed, pink morning glory and cattail.[141] Common submerged aquatic plants include those from the genus Aponogeton, Potamogeton and the highly invasive Hydrilla, Elodea.[142] Free floating Lemna, Wolffia and Eichhornia are common. Rooted floating plants include weeds, lilies and lotus.[142] Around 22 types of aquatic weeds are found in the lakes including algae, duckweed, water hyacinth, musk grass, water thyme, pondweed.[143]

Plankton

[edit]The 1989 Birdwatchers' Field Club study recorded 113 forms of plankton; in terms of plankton diversity six out of the 72 lakes showed high diversity.[124] In a doctoral study on algae from 2017 to 2019 one downstream and one upstream lake from each of the 6 lake series were targeted.[144] Algal diversity observed included 124 species belonging to 58 genera of the four classes Chlorophyceae, Cyanophyceae, Bacillariophyceae and Euglenophyceae.[144] Dominant taxa includes the species Scenedesmus dimorphus and species from the genus Anabaena.[144] In a targeted study of 7 lakes between 2010 and 2012 the dominant classes were the same.[145] Microcystis aeruginosa was the most dominant algal bloom. The main zooplankton were rotifera, cladocera, ostracoda and copepoda.[145]

Other

[edit]An inventory of lakes in Bangalore conducted between 2016 and 2018 identified 142 types of flora 191 types of fauna,[146] belonging to nine categories of the biota (flora: trees, herbs and shrubs, aquatic flora; fauna: insects, macro benthic fauna, fish, herpetofauna, avifauna, mammals) in and around the water bodies.[147]

Various trees, herbs and shrubs are found in and around the lakes.[148] Aacia nilotica has been planted at various tanks.[149] Floral diversity of wetlands include types of flowering and fruiting plants.[150]

A 2016 study identified 116 butterfly species.[151] Doddakallasandra lake and Madivala lake have seen efforts specific to butterfly biodiversity.[152][153] Apharitis lilacinus has been spotted at Hesaraghatta Lake.[154]

One of the, or the, most vital modern use of lakes is for the storage of freshwater and subsequent recharge of groundwater in Bangalore. This comes into question during efforts to enhance the biodiversity and aesthetics of the lakes through the creation of artificial islands and tree parks, and opposition to "soup bowl" structured restoration.[155][156] Naturalist Zafar Futehally suggests a balance by restricting soup bowl structure to select lakes, and allowing the others to develop with more concern for aquatic birds and recreation.[156] In 2023 The New York Times reported about conservationist Anand Malligavad who has restored 35 lakes in Bengaluru, with the help ancient Chola methods of water management, which don't need maintenance.[157]

List of lakes and tanks

[edit]Greater Bangalore

[edit]Larger than 100 acres

[edit]

6 to 100 acres

[edit]

Former reservoirs

[edit]Other lakes in Urban District

[edit]

| Name | Area (acres) | Coordinates |

|---|---|---|

| Greater than 100 acres | ||

| Hesaraghatta | 1912[253] | 13°09′27″N 77°29′20″E / 13.1574°N 77.4888°E |

| Byramangala | 12°45′55″N 77°25′28″E / 12.7654°N 77.4244°E | |

| Varanasi Lake | 13°01′35″N 77°41′12″E / 13.026383°N 77.686585°E | |

| Muthanallur | 600[254] | 12°49′20″N 77°43′42″E / 12.8221°N 77.7282°E |

| Hennagara | 172[169] | 12°46′39″N 77°39′41″E / 12.7776°N 77.6614°E |

References

[edit]- Notes

- Citations

- ^ "A 'thousand lakes' once fed now-parched Bengaluru". 15 March 2024.

- ^ Roy, Labonie (20 September 2021). "A to Z guide to Bengaluru's lakes". Citizen Matters, Bengaluru. Citizen Matters (Also published by Mongabay). Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ a b c D'souza, Rohan (31 August 2014). "When lakes were tanks". Down to Earth. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- ^ Baindur, Meera (2014). "Bangalore Lake story: reflections on the spirit of a place". Journal of Cultural Geography. 31 (1). Taylor & Francis: 37. doi:10.1080/08873631.2013.873296. ISSN 0887-3631. S2CID 144375360.

- ^ a b D'Souza, Rohan (2017). "Contested Governance of Wetlands in Bangalore". Jindal Journal of Public Policy. 3 (1): 71–80. doi:10.54945/jjpp.v3i1.113. S2CID 257442682.

- ^ Srinivas 2001, p. 38, Although natural lakes existed in the region, these manmade "tanks," as they are commonly called in south India ... Since it is difficult to say which bodies of water were natural and which manmade, I use the word "tank" to designate any such body in the Bangalore region..

- ^ Srinivas 2001, p. 51.

- ^ Reddy, M. S.; Char, N. V. V. (10 March 2004), Management of Lakes in India (PDF), World Lakes Website

- ^ Protection and Management of Urban Lakes in India (Report). Centre for Science and Environment. 2012.

- ^ Jainer, Shivali (3 January 2020). "How do India's policies and guidelines look at 'urban lakes'?". Down to Earth. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ a b Rao, Mohit M. (19 October 2020). "Katte and Kunte: The smaller, lesser-known water bodies that Bengaluru is losing to concrete". Scroll.in. Retrieved 29 September 2022.

- ^ Nagendra 2016, p. 164-165, Chapter 9.

- ^ Nagendra, Harini (September 2010). "Maps, lakes and citizens" (PDF). Seminar (613): 19–23 – via Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment (ATREE).

- ^ VL, Prakash (22 April 2022). "Bengaluru's rajakaluves are in dire need of attention". Bangalore Mirror. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ a b c Ranganathan, Malini (2015). "Storm Drains as Assemblages: The Political Ecology of Flood Risk in Post-Colonial Bangalore: Stormwater Drains as Assemblages". Antipode. 47 (5): 1300–1320. doi:10.1111/anti.12149. eISSN 1467-8330. ISSN 0066-4812 – via Wiley.

- ^ Thomas, Bellie (4 February 2022). "A step back in time". Bangalore Mirror. Retrieved 16 November 2022.

- ^ a b Srinivas 2001, p. 42.

- ^ a b Nagendra 2016, p. 160-161, Chapter 9.

- ^ D'Souza, Rohan s (2007). "Impact of Privatisation of Lakes in Bangalore". Centre for Education and Documentation. Archived from the original on 29 October 2008. Retrieved 8 September 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Lele, Sharachchandra; Sengupta, Mrinalini Bakshi (2018). "From lakes as urban commons to integrated lake-water governance: The case of Bengaluru's urban water bodies" (PDF). South Asian Water Studies (SAWAS). 8 (1): 5–26 – via atree.org.

- ^ Nagendra, Harini (22 June 2015). "Blessings and curses: the construction of lakes in Bengaluru". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- ^ a b Nagendra 2016, p. 162-166, Chapter 9.

- ^ Sen, Amrita; Unnikrishnan, Hita; Nagendra, Harini (2021). "Restoration of Urban Water Commons: Navigating Social-Ecological Fault Lines and Inequities". Ecological Restoration. 39 (1): 120–129. doi:10.3368/er.39.1-2.120. ISSN 1543-4079. S2CID 235362713.

- ^ Nagendra 2016, p. 164, 166-168, Chapter 9.

- ^ Shah 2003, p. vi.

- ^ a b c Chandran, Rahul (15 October 2016). "Like Bengaluru's lakes, the Neerghantis are disappearing". Livemint. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- ^ Shah 2003, p. vii, 59.

- ^ Kaggere, Niranjan (3 October 2021). "Project to rejuvenate city's groundwater brings livelihood, respect to traditional well-diggers". Deccan Herald. Retrieved 20 November 2022.

- ^ Coushik, Ramya (7 October 2020). "The Indian megacity digging a million wells". BBC. Retrieved 20 November 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g Unnikrishnan, Hita; Manjunatha, B; Nagendra, Harini (2016). "Contested urban commons: mapping the transition of a lake to a sports stadium in Bangalore". International Journal of the Commons. 10 (1): 265–293. doi:10.18352/ijc.616. hdl:10535/10025. ISSN 1875-0281. S2CID 147676903.

- ^ Menezes, Naveen (11 April 2022). "Sampangi Tank, centre of Karaga festivities, to be spruced up". Deccan Herald. Retrieved 20 November 2022.

- ^ Nagendra 2016, p. 175-177, Chapter 9. Changes in Governance and the Decay of Lakes..

- ^ Mundoli, Seema; Unnikrishnan, Hita; Manjunatha, B.; Nagendra, Harini (24 June 2015). "The sacred lakes of Bengaluru". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- ^ Sen, Amrita; Nagendra, Harini (2021). "The differentiated impacts of urbanisation on lake communities in Bengaluru, India". International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development. 13 (1): 17–31. Bibcode:2021IJUSD..13...17S. doi:10.1080/19463138.2020.1770260. ISSN 1946-3138. S2CID 219745918.

- ^ a b Castán Broto, Vanesa; Sudhira, H S; Unnikrishnan, Hita (2021). "Walk the Pipeline : Urban Infrastructure Landscapes in Bengaluru's Long Twentieth Century". International Journal of Urban and Regional Research. 45 (4): 696–715. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.12985. ISSN 0309-1317. S2CID 234087370.

- ^ a b Smitha, K. C. (2004). "Urban Governance and Bangalore Water Supply & Sewerage Board (BWSSB)" (PDF). Bangalore: Institute of Social and Economic Change. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 July 2006.

- ^ a b c Bareuther, Mischa; Klinge, Michael; Buerkert, Andreas (2020). "Spatio-Temporal Dynamics of Algae and Macrophyte Cover in Urban Lakes: A Remote Sensing Analysis of Bellandur and Varthur Wetlands in Bengaluru, India". Remote Sensing. 12 (22): 3843. Bibcode:2020RemS...12.3843B. doi:10.3390/rs12223843. ISSN 2072-4292.

- ^ Unnikrishnan, Hita; B., Manjunatha; Nagendra, Harini; Castán Broto, Vanesa (2020). "Water governance and the colonial urban project: the Dharmambudhi lake in Bengaluru, India". Urban Geography. 42 (3): 263–288. doi:10.1080/02723638.2019.1709756. ISSN 0272-3638. S2CID 213788797.

- ^ a b Nagendra, Harini; Unnikrishnan, Hita (Spring 2019). "The Lake That Became a Bus Terminus". Arcadia (2). Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. doi:10.5282/RCC/8493. ISSN 2199-3408 – via Environment & Society Portal.

The story of Dharmambudhi lake is thus one of the transformation of an urban commons to ...

- ^ Bharadwaj, K. V. Aditya (30 May 2019). "Majestic @ 50: When our bus station was a lake..." The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 23 November 2022.

- ^ "Err- bane Truth - Dharmambudhi Tank". TheWaterChannel. Nishant Ratnakar and Badekkila Pradeep. 2010. Retrieved 23 November 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b Pai, Roopa (7 June 2022). "The welcoming ways of Gandhinagar". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 23 November 2022.

- ^ a b Unnikrishnan, Hita; Nagendra, Harini (2017). "Of Flash Floods and a Lost Indian Waterscape". The Nature of Cities. Retrieved 20 September 2022.

- ^ G N, Prashanth (9 November 2014). "Dharmambudhi, from a water tank to a bus station". Deccan Herald. Retrieved 23 November 2022.

- ^ a b c d e "Once a beautiful lake". ENVIS Centre. Archived from the original on 9 April 2009. Retrieved 8 September 2022.

The Kempegowda Bus Stand located on the once Dharmambudhi Lake.

- ^ Chandra NS, Subhash (15 September 2009). "Vanishing lakes: Time to act now". Deccan Herald. Retrieved 8 September 2022.

- ^ a b Inglis, Patrick (2019). Narrow Fairways: Getting by and Falling Behind in the New India. Oxford University Press. pp. 40–42. ISBN 978-0-19-066476-3 – via Google Books.

- ^ Inglis, Patrick (2019). "6. 'Take This Land' A Brief History of the Karnataka Golf Association". In Jodhka, Surinder S.; Naudet, Jules (eds.). Mapping the Elite: Power, Privilege, and Inequality. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-909791-3 – via Google Books.

- ^ "KGA History". Karnataka Golf Association. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- ^ Report of the expert committee for preservation, restoration or otherwise of the existing tanks in Bangalore metropolitan area (PDF) (Report). 1986. via indiawaterportal.org

- ^ "A Major Milestone". Lake Development Authority. Archived from the original on 5 April 2009.

- ^ Thippaiah 2009, p. 7-8.

- ^ "BBMP gets custody of 38 lakes". The Hindu. 14 December 2019. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- ^ "Minor Irrigation Department to look after Bengaluru lakes?". Deccan Chronicle. 26 January 2018. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- ^ Kozhisseri, Deepa (15 May 2008). "Bangalore lakes leased out". Down to Earth. Retrieved 21 November 2022.

- ^ Swaraj, Shilpa M. (21 July 2022). "Whom do you call to fix your lake?". Citizen Matters, Bengaluru. Retrieved 21 November 2022.

- ^ "Performance audit on Conservation and Ecological restoration of Lakes under the jurisdiction of Lake Development Authority and Urban Local Bodies" (PDF). Report of the Comptroller and Auditor General of India. 2015. p. 7.

Entities involved in conservation and restoration of lakes

- ^ a b Thakur, Aksheev (13 February 2022). "Lakes of Bengaluru: Chunchaghatta lake restored, experts recommend ways to improve water quality". The Indian Express. Retrieved 25 September 2022.

- ^

- "More lakes to be restored from CSR funds, says Minister". The Hindu. 13 February 2021. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 25 September 2022.

- Kulkarni, Chiranjeevi (13 January 2020). "Drive to restore Jakkur Lake wins praise". Deccan Herald. Retrieved 25 September 2022.

- "Meet mechanical engineer Anand Malligavad, who left his job to revive Bengaluru's dying lakes". The Indian Express. 17 January 2022. Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- Chowdhury, N. Noireeta (September 2019), Analysing the influence of institutional arrangements on sustainability of lake basins in Bangalore, India, Institute for Housing and Urban Development Studies, Erasmus University Rotterdam

- Selvam, Divya; V, Aishwarya (30 July 2019). "In Bengaluru, citizen groups lead the way in revival of lakes". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- ^

- Khanna, Bosky (13 February 2020). "Lake revival action faulty, say greens, civic groups". The New Indian Express. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- Venkatesh, Sangeeta (15 November 2019). "Case Study: Successful Rejuvenation of a Bengaluru lake". Clean India Journal. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

The rehabilitation and rejuvenation of Kundalahalli Lake ...

- "Urban waterbodies. The Essence of Waterbody Rejuvenation. Lake Rejuvenation Process". Lakes Department. Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike.

Waterbody rejuvenation encompasses the following ... Restoring ... Conserving ... Reviving ... Managing

- Thakur, Aksheev (19 June 2022). "Lakes of Bengaluru: BBMP begins rejuvenation of Gowdanakere; activists call desilting process faulty". The Indian Express. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- Staff Reporter (4 March 2021). "Concerns over restoration process of Doddakallasandra lake". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 15 November 2022.

- ^ Thippaiah 2009, p. 26-28.

- ^ Thippaiah 2009, p. 10.

- ^ a b "Karnataka panel confirms 11,000 acres lake land encroached in Bengaluru". Business Standard India. 8 January 2016. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- ^ Sengupta, Sushmita (12 January 2016). "Karnataka government reveals sad state of Bengaluru lakes". Down to Earth. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- ^ "Lake land grabbers get time till March 31". Bangalore Mirror. 16 March 2016. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- ^ a b "About lakes of Bangalore". Lake Development Authority. Archived from the original on 5 April 2009.

- ^ a b "Study Area: Bangalore". Centre for Ecological Sciences, IISc. Archived from the original on 16 July 2012. Retrieved 29 November 2008.

- ^ Chakrapani et al. 1990, p. 6.

- ^ Chakrapani et al. 1990, p. 60.

- ^ Chakrapani et al. 1990, p. 5.

- ^ Chakrapani et al. 1990, p. 1, 4.

- ^ Chakrapani et al. 1990, p. 4.

- ^ "Report of the Comptroller and Auditor General of India Performance audit of Management of storm water in Bengaluru Urban area, Government of Karnataka" (PDF). Comptroller and Auditor General. 2021. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- ^ Mathew, Melvin (20 September 2022). "Stormwater drain chasers". Bangalore Mirror. Retrieved 24 September 2022.

- ^ "A tale of vanishing lakes and drains that bring the city to its knees during rain". The Hindu. 27 September 2022. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- ^ "Bengaluru civic body starts to clear encroachments on storm-water drains". The Hindu. 3 September 2022. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 24 September 2022.

- ^ NS, Subhash Chandra; Moudgal, Sandeep (15 September 2009). "Vanishing lakes: Time to act now. Storm water drain encroachments: A major lake-killer". Deccan Herald. Retrieved 23 September 2022.

- ^ Gowda, K.; Sridhara, M.V. (2006). "Conservation of Tanks/Lakes in the Bangalore Metropolitan Area". In Manolas, Evangelos I. (ed.). Proceedings of the 2006 Naxos International Conference on Sustainable Management and Development of Mountainous and Island Areas (PDF). Democritus University of Thrace. pp. 122–130. ISBN 960-89345-0-8.

- ^ a b c Subramanian 1985, p. 76.

- ^ "Bengaluru city sets new record for highest annual rainfall". The Indian Express. 18 October 2022. Retrieved 14 December 2022.

- ^ "Bengaluru creates rain record, experts warn of more havoc in days to come". The New Indian Express. 20 October 2022. Retrieved 14 December 2022.

- ^ a b Sudhira, H.S.; Ramachandra, T.V.; Subrahmanya, M.H. Bala (2007). "Bangalore". Cities. 24 (5): 379–390. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2007.04.003.

- ^ Mani 1985, p. 3.

- ^ Small, C. (2006), Urban Landsat: Cities from Space, Palisades, NY: NASA Socioeconomic Data and Applications Center (SEDAC), doi:10.7927/h4sq8xb1, retrieved 25 December 2022

- ^ Thippaiah 2009, p. 4-5.

- ^ Thippaiah 2009, p. 4-7.

- ^ Thippaiah 2009, p. 6.

- ^ Chaturvedi, Atul (16 June 2015). "BBMP jurisdiction 'shrinks' from 800 to 712 sq km". Bangalore Mirror. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

- ^ a b Ramachandra, T. V.; Mujumdar, Pradeep P. (2009). "Urban Floods: Case Study of Bangalore". Journal of the National Institute of Disaster Management. 3 (2): 1–98.

- ^ a b Chandra NS, Subhash (14 April 2008). "Burgeoning Bangalore City saps its lakes dry". Deccan Herald. Archived from the original on 21 April 2008. Retrieved 8 September 2022.

- ^ a b Brinkmann, Katja; Hoffmann, Ellen; Buerkert, Andreas (17 February 2020). "Spatial and Temporal Dynamics of Urban Wetlands in an Indian Megacity over the Past 50 Years". Remote Sensing. 12 (4): 662. Bibcode:2020RemS...12..662B. doi:10.3390/rs12040662. ISSN 2072-4292.

- ^ Chatterjee, Biplob; Roy, Aparna (2021). Creating Urban Water Resilience in India: A Water Balance Study of Chennai, Bengaluru, Coimbatore, and Delhi (PDF). Observer Research Foundation. p. 62. ISBN 978-93-90494-44-6.

- ^ "Panel lambasts BBMP, BDA for inability to save lakes". The Hindu. 13 March 2020. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- ^ Manjusainath, G (23 September 2015). "Now, see the lake loot tale in black and white". Deccan Herald. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- ^ Bharadwaja, Dr Ajaya S. (11 January 2016). "Bengaluru lost its water bodies, and here's what is remaining". Citizen Matters, Bengaluru. Retrieved 23 September 2022.

- ^ G, Sankar C. (13 June 2012). "With no power to protect lakes, LDA limps". Citizen Matters, Bengaluru. Retrieved 18 September 2022.

- ^ "'Encroached lake land worth Rs 24K cr'". Deccan Herald. 26 July 2014. Retrieved 23 September 2022.

- ^ a b c d Pickard, Amy; White, Stella; Bhattacharyya, Sumita; Carvalho, Laurence; Dobel, Anne; Drewer, Julia; Jamwal, Priyanka; Helfter, Carole (December 2021). "Greenhouse gas budgets of severely polluted urban lakes in India". Science of the Total Environment. 798: 149019. Bibcode:2021ScTEn.79849019P. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.149019. PMID 34325140.

- ^ Sastry, Aishwarya; Patel, Niqat; Arora, Shubhda (3–5 December 2017). Ekstrand, Eva Åsén; Findahl, Olle (eds.). The City of Burning Lakes: Media representation of an environmental disaster in Bangalore City. Consuming the Environment 2017. Multidisciplinary approaches to urbanization and vulnerability. Sweden: University of Gävle. pp. 37–53. ISBN 978-91-88145-23-9.

- ^ a b Lokeshwari, H.; Chandrappa, G. T. (2006). "Impact of heavy metal contamination of Bellandur Lake on soil and cultivated vegetation". Current Science. 91 (5): 622–627. ISSN 0011-3891. JSTOR 24094365.

- ^ Driver, Berjis (16 October 2020). "Restoring groundwater in urban India: Learning from Bengaluru". ORF. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ Kidwai, Nehal. Achom, Debanish (ed.). "Residents Fume As Toxic Froth Builds Up In Lake Near Bengaluru". NDTV.com. Retrieved 21 November 2022.

- ^ D'Souza, Pearl Maria (12 May 2019). "It's froth all over again in Bengaluru's Byramangala lake". The New Indian Express. Retrieved 21 November 2022.

- ^ Ravikumar, P.; Aneesul Mehmood, Mohammad; Somashekar, R. K. (January 2013). "Water quality index to determine the surface water quality of Sankey tank and Mallathahalli lake, Bangalore urban district, Karnataka, India". Applied Water Science. 3 (1): 247–261. Bibcode:2013ApWS....3..247R. doi:10.1007/s13201-013-0077-2. ISSN 2190-5487. S2CID 178533882.

- ^ Birawat, Khushbu K.; T, Hymavathi; C.Nachiyar, Mathuvanthi; N.A, Mayaja; C.V, Srinivasa (2021). "Impact of urbanisation on lakes—a study of Bengaluru lakes through water quality index (WQI) and overall index of pollution (OIP)". Environmental Monitoring and Assessment. 193 (7): 408. Bibcode:2021EMnAs.193..408B. doi:10.1007/s10661-021-09131-w. ISSN 0167-6369. PMID 34114104. S2CID 235398593.

- ^ a b "National Water Quality Monitoring Programme (GEMS & MINARS)" (PDF). Karnataka State Pollution Control Board. Retrieved 21 November 2022.

- ^ Thakur, Aksheev (1 September 2022). "Water in all Bengaluru lakes unfit for drinking, says state pollution control board study". The Indian Express. Retrieved 23 September 2022.

- ^ a b c d Verma, Rinku; Singh, S. P.; Raj, K. Ganesha (2003). "Assessment of changes in water-hyacinth coverage of water bodies in northern part of Bangalore city using temporal remote sensing data". Current Science. 84 (6): 795–804. ISSN 0011-3891. JSTOR 24107584.

- ^ Benjamin, Ranjeev; Chakrapani, B. K.; Devashish, Kar; Nagarathna, A. V.; Ramachandra, T. V. (December 1996). "Fish Mortality in Bangalore Lakes, India". Electronic Green Journal. 1 (6). doi:10.5070/G31610252. S2CID 53320131 – via Centre for Ecological Sciences, IISc.

- ^ Kozhisseri, Deepa (31 July 2005). "Fishy deaths". Down to Earth. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ Maheshwari, Ramesh (2005). "Fish death in lakes". Current Science. 88 (11): 1719–1721. ISSN 0011-3891. JSTOR 24110328 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Vyas, Ananya (19 July 2022). "[Explainer] What's causing mass fish death in India's ponds and lakes?". Mongabay-India. Retrieved 12 December 2022.

- ^ Gorain, Bisweswar; Parama, VR Ramakrishna; Paul, Srijita (2018). "Impact of Idol Immersion Activities on the Water Quality of Hebbal and Bellandur Lakes of Bengaluru in Karnataka". Journal of Soil Salinity and Water Quality. 10 (1): 112–117.

- ^ Gorain, Bisweswar; Paul, Srijita (2019). "Effect of idol immersion activities on the water quality of urban lakes in Bengaluru, Karnataka". Current World Environment. 14 (1): 143–148. doi:10.12944/CWE.14.1.13. S2CID 164313421.

- ^ Sharma, Dinesh C (2004). "Rituals Cause Lead Exposure and Fish Kill". Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. 2 (10): 510. Bibcode:2004FrEE....2..510S. ISSN 1540-9295. JSTOR 3868375.

- ^ a b "Over 1.50 lakh Ganesha idols immersed in BBMP limits". Deccan Herald. 2 September 2022. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ a b c d Ramachandra, T. V.; Mahapatra, Durga Madhab (2016). "The Science of Carbon Footprint Assessment". In Muthu, Subramanian Senthilkannan (ed.). The Carbon Footprint Handbook. CRC Press. Taylor & Francis. pp. 33, 35. ISBN 978-1-4822-6223-0.

- ^ a b c "Urban Wetlands. Reviving Bangalore's wetlands" (PDF). Biome Environmental. Retrieved 25 December 2022.

- ^ Waterbody Rejuvenation – A Compendium of Case Studies (PDF), Consortium for DEWATS Dissemination (CDD) Society, Bengaluru, December 2019, p. 70

- ^ Thakur, Aksheev (4 October 2017). "Bengaluru: The floating islands that clean Agara, Madiwala lakes". Deccan Chronicle. Retrieved 25 December 2022.

- ^ a b Jha, Ramanath (15 October 2022). "The Bengaluru floods: The rising challenge of urban floods in India". ORF. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ National Disaster Management Guidelines : Management of Urban Flooding (PDF). New Delhi: National Disaster Management Authority. September 2010. p. 114. ISBN 978-93-80440-09-5.

- ^ a b c d Krishna, M. B.; Subramanya, S.; Prasad, J. N. (1994). George, Joseph (ed.). Annotated Checklist of The Birds of Bangalore. Birdwatchers' Field Club of Bangalore. pp. 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b Chakrapani et al. 1990, p. 46-48.

- ^ a b c d e f g Krishna, M. B.; Chakrapani, B. K.; Srinivasa, T. S. (1996), "Annual Waterbird Census in and around Bangalore and Maddur", Water Birds And Wetlands Of Bangalore, Birdwatchers' Field Club of Bangalore and Bangalore Urban Division, Karnataka State Forest Department, pp. 59–79

- ^ a b c Jambhekar, Ravi; Suryawanshi, Kulbhushansingh; Nagendra, Harini (22 January 2021). "Relationship between lake area and distance from the city centre on lake-dependent resident and migratory birds in urban Bangalore, a tropical mega-city in Southern India". Journal of Urban Ecology. 7 (1): juab028. doi:10.1093/jue/juab028. ISSN 2058-5543.

- ^ Rajashekara, S.; Venkatesha, M. G. (2011). "Community composition of aquatic birds in lakes of Bangalore, India". Journal of Environmental Biology. 32 (1): 77–83. ISSN 0254-8704. PMID 21888236.

- ^ Antoney, P.U.; Swetha, K.S.; Sreepad, S. (January–June 2007). "Avian Diversity in the Wetland of Bangalore". Mapana Journal of Sciences. 6 (1): 57–68. doi:10.12723/mjs.10.5. ISSN 0975-3311.

- ^ Rajashekara, S.; Venkatesha, M. G. (2010). "The diversity and abundance of waterbirds in lakes of Bangalore city, Karnataka, India". Biosystematica. 4 (2): 68–69. eISSN 0973-7871. ISSN 0973-9955.

- ^ Chakrapani et al. 1990, p. 48-49.

- ^ Pereira, Joiston (19 June 2016). "Bird Poaching in Bangalore's Wetlands". conservationindia.org. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- ^ a b Centre for Lake Conservation (EMPRI), Inventorisation of Water Bodies in Bengaluru Metropolitan Area (2018), p. 138.

- ^ Girisha (30 January 2021). "Indigenous fishes have been dwindling in Bengaluru's rivers and lakes". The News Minute. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ^ Ramprasad, V (27 August 2022). "Bengaluru: Refreshed lakes, dying fish". Deccan Herald. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ^ Mathew, Melvin (5 June 2022). "Man vs bird". Bangalore Mirror. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ^ a b c G, Sreekala (May 2013). "Biochemical studies on tissues of major carps from lakes of Bangalore". Thesis for Doctor of Philosophy in Zoology. Bangalore University. pp. 37, 38, 49, 97. hdl:10603/70248 – via Shodhganga.

- ^ a b Pinglay-Plumber, Prachi (5 April 2021). "The story of Jakkur lake sets an example for inclusive rejuvenation projects". Mongabay-India. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- ^ "Bangalore and its Lakes" (PDF). bengaluru.urbanwaters.in. Biome Environmental. 2017.

- ^ a b c Jayanth, K. P. (1987). "Suprression of Water Hyacinth by the exotic insect Neochetina eichhorniae in Bangalore, India". Current Science. 56 (10): 494–495. ISSN 0011-3891. JSTOR 24091336.

- ^ "Four harvesters to clear weeds in Bellandur Lake". The New Indian Express. 2 May 2017. Retrieved 3 December 2022.

- ^ Centre for Lake Conservation (EMPRI), Inventorisation of Water Bodies in Bengaluru Metropolitan Area (2018), p. 131.

- ^ a b Centre for Lake Conservation (EMPRI), Inventorisation of Water Bodies in Bengaluru Metropolitan Area (2018), p. 133.

- ^ Centre for Lake Conservation (EMPRI), Inventorisation of Water Bodies in Bengaluru Metropolitan Area (2018), p. 135.

- ^ a b c Veenashree (July 2021). "Environmental assessment of harmful algal blooms and eutrophication in lakes of Bengaluru - A climate change perspective" (PDF). Thesis for DPhil in Environmental Science. Bangalore University. pp. 76, 220 – via Shodhganga.

- ^ a b Gayathri, S. (2014). "Studies on progressive eutrophication and restoration strategies of few Bangalore lakes". Bangalore University. pp. 128, 202. hdl:10603/127460 – via Shodhganga.

- ^ Rao, Mohit M. (20 November 2017). "City lakes support 333 types of flora and fauna". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- ^ Centre for Lake Conservation (EMPRI), Inventorisation of Water Bodies in Bengaluru Metropolitan Area (2018), p. iii.

- ^ Centre for Lake Conservation (EMPRI), Inventorisation of Water Bodies in Bengaluru Metropolitan Area (2018), p. 129-130.

- ^ Chakrapani et al. 1990, p. 29.

- ^ N., Nandini; Jumbe, Aboud S. (2009). "2. Wetlands". State of Environment Report Bangalore 2008 (PDF). EMPRI, DoFEE, GoK, GTZ. pp. 50–51 – via Centre for Science and Environment.

- ^ Shet R, Chaturved (28–30 December 2016). Butterfly Diversity of Bangalore Urban District. Lake 2016: Conference on Conservation and Sustainable Management of Ecologically Sensitive Regions in Western Ghats – via ResearchGate.net.

- ^ Tejaswi, Mini (13 July 2019). "Butterfly survey at Doddakallasandra lake unearths promising results". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 15 November 2022.

- ^ H.M, Shruthi (24 June 2018). "Madivala lake transforms into biodiversity park". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- ^ Kunte, Krushnamegh; Ravikanthachari, Nitin (2020). "Butterflies of Bengaluru" (PDF). Karnataka Forest Department (Research Wing), National Centre for Biological Sciences, and Indian Foundation for Butterflies, Bengaluru, India. pp. 110–112.

- ^ Nagendra, Harini (September 2010). "Maps, lakes and citizens" (PDF). Seminar (613): 22 – via Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment (ATREE).

- ^ a b Futehally, Zafar (15 February 2010). "Soup bowls, good or bad?". Deccan Herald. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ Yasir, Sameer (22 September 2023). "India's 'Lake Man' Relies on Ancient Methods to Ease a Water Crisis". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 28 September 2023.

- ^ "HC stays construction of artificial islands in Begur lake". The Hindu. 30 August 2019. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ Siraj, M. A. (22 November 2013). "Yet another lake is dying". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 17 September 2022.

- ^ Thakur, Aksheev (9 January 2022). "Lakes of Bengaluru: When a defence PSU stepped in to revive the Doddabommasandra lake". The Indian Express. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ "After revival, Doddanekundi Lake back on its death-bed". Deccan Chronicle. 23 November 2019. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ "Oldest and biggest lakes in bengaluru". The New Indian Express. 4 April 2017. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ "800 houses flooded after Bengaluru's Hulimavu lake breaches". The Hindu. 24 November 2019. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ a b c d Murphy, Ailbhe (2017). Making Space in a Megacity. The Evolving Stewardship of Bangalore's Urban Lakes (PDF) (Master Thesis in Social-Ecological Resilience for Sustainable Development thesis). Stockholm Resilience Centre.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Ramachandra, T V; Asulabha, K S; Sincy, V; Bhat, Sudarshan; Aithal, Bharath H. (2016). Wetlands: Treasure of Bangalore. ENVIS Technical Report 101. Encroachment of Lakes (Report). Energy & Wetlands Research Group, CES, IISc, Bangalore, India. Also see PDF version.

- ^ a b Menezes, Naveen (12 June 2022). "Revival hopes for Rampura lake may come unstuck over work delays". Deccan Herald. Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- ^ Thakur, Aksheev (28 November 2021). "Lakes of Bengaluru: Rachenahalli lake, a lifeline choked by rampant development". The Indian Express. Retrieved 16 September 2022.

- ^ a b c "167 Lakes in BBMP Custody". Lakes Department, Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike. Retrieved 16 December 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ramachandra T V, Bharath H. Aithal, Alakananda B and Supriya G, 2015. Environmental Auditing of Bangalore Wetlands, ENVIS Technical Report 72, CES, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore. pg 7, 58, 84, 91, 140.

- ^ "Bengaluru: Green Tribunal directs authorities to submit report on action against Yele Mallappa Shetty Lake encroachments". The Indian Express. 14 March 2022. Retrieved 24 September 2022.

- ^ M, Akshatha (22 April 2015). "HC pushes for restoration and rejuvenation of Agara and Bellandur lakes". Citizen Matters, Bengaluru. Retrieved 10 September 2022.

- ^ Thakur, Aksheev (21 May 2022). "Lakes of Bengaluru: Pollution in Amruthahalli lake affects economic dependency of people live near the waterbody". The Indian Express. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ a b Ramachandra T V, Vinay S, Asulabha K S, Sincy V, Sudarshan Bhat, Durga Madhab Mahapatra, Bharath H. Aithal, 2017. "Encroachment of Lakes and Natural Drains" Rejuvenation Blueprint for lakes in Vrishabhavathi valley, ENVIS Technical Report 122, Environmental Information System, CES, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore

- ^ Manjusainath, G; Kappan, Rasheed (10 May 2015). "Banaswadi, rebuilding a lake". Deccan Herald. Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- ^ Fathima, Iffath (25 July 2019). "Residents full of plans for freshly-rejuvenated Benniganahalli lake". The New Indian Express. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ Boray, Chetan (28 July 2010). "Jayanagar's lake: Almost sold, now saved". Citizen Matters, Bengaluru. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ "Palike recovers land worth Rs 13 crore". Deccan Herald. 26 August 2014. Retrieved 20 September 2022.

- ^ Thakur, Aksheev (7 August 2022). "Lakes of Bengaluru: Restored in 2019 but entry of sewage still a problem in Devasandra lake". The Indian Express. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ Kulkarni, Chiranjeevi (19 July 2020). "11 encroachers continue to occupy 40-acre Doddabidarakallu Lake". Deccan Herald. Retrieved 17 September 2022.

- ^ B R, Gururaj (14 August 2018). "Scenic, serene water body in Bengaluru's Gangondanahalli is now Lake putrid". Bangalore Mirror. Retrieved 16 December 2022.

- ^ TV, Ramachandra; HS, Sudhira (September 2013). "Present status of Gottigere Tank : Indicator of Decision maker's apathy". Centre for Ecological Sciences, Indian Institute of Science.

- ^ Khanna, Bosky (22 September 2014). "New lease of life for Herohalli lake". Deccan Herald. Retrieved 17 September 2022.

- ^ Thakur, Aksheev (1 May 2022). "Lakes of Bengaluru: At Rs 2.5 crore, Hoodi Lake is now a rejuvenated waterbody". The Indian Express. Retrieved 24 September 2022.

- ^ Yajaman, Arathi Manay (2 July 2013). "Saving the lakes of Horamavu". Citizen Matters, Blogs. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ Thakur, Aksheev (24 July 2022). "Lakes of Bengaluru: Once a symbol of pristine environment, Hosakerehalli lake cries for rejuvenation". The Indian Express. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ Fathima, Iffath (1 July 2019). "Bengaluru's Iblur lake regains lost beauty". The New Indian Express. Retrieved 23 September 2022.

- ^ Thakur, Aksheev (27 March 2022). "Janardhana Kere: A lake that even Google Map fails to find". The Indian Express. Retrieved 17 September 2022.

- ^ "Days numbered for Kacharakanahalli lake?". The Hindu. 21 June 2015. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ Menezes, Naveen (1 March 2021). "Battered Kaggadasapura lake up for rejuvenation". Bangalore Mirror. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ "Nirmala Sitharaman visits Kalena Agrahara Lake in Bengaluru". The Hindu. 15 May 2022. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ Mundoli, Seema; Dechamma, C. S.; Auddy, Madhureema; Sanfui, Abhiri; Nagendra, Harini (2022), Narain, Vishal; Roth, Dik (eds.), "A New Imagination for Waste and Water in India's Peri-Urban Interface", Water Security, Conflict and Cooperation in Peri-Urban South Asia, Cham: Springer International Publishing, p. 30, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-79035-6_2, ISBN 978-3-030-79034-9, S2CID 245095228 (subscription required)

- ^ Thakur, Aksheev (3 July 2022). "Bengaluru: The tale of two Byrasandra lakes". The Indian Express. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ Centre for Lake Conservation (EMPRI), Inventorisation of Water Bodies in Bengaluru Metropolitan Area II.2 2018, p. 1022.

- ^ "Kempambudi lake to be a tourist hub: Mayor". The Hindu. 3 May 2012. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ B P, Darshan Devaiah (17 September 2018). "Kengeri Lake still waits for second shot at life". Deccan Herald. Retrieved 16 September 2022.

- ^ "167 Lakes in BBMP Custody". Lakes Department, Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ Thakur, Aksheev (28 April 2019). "Konasandra Lake is gasping for life, no funds to fix it, says BBMP". Deccan Chronicle. Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- ^ Thakur, Aksheev (24 April 2022). "Lakes of Bengaluru: Resident bodies press authorities to pull up socks before monsoon to save Kothanur Lake from getting polluted". The Indian Express. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ Raj, Arpita (29 October 2017). "Kowdenahalli Lake transforms from swamp to ecological haven". The Times of India. Retrieved 16 September 2022.

- ^ "The untapped leisure potential of Bengaluru lakes". The Hindu. 22 September 2016. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 16 September 2022.

- ^ "Save Lalbagh lake from certain death". Deccan Herald. 13 March 2022. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ "Tale of the unlucky Lakkasandra lake". The Hindu. 18 October 2012. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ Thakur, Aksheev (20 August 2021). "Bengaluru: Environmentalists slam BBMP's 51-crore development plans for Mallathahalli Lake". The Indian Express. Retrieved 17 September 2022.

- ^ "Death of Mathikere lake". The New Indian Express. 16 January 2013. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ "1 MLD DEWATs at Mahadevpura Lake, Bangalore". www.cseindia.org. Centre for Science and Environment. Retrieved 16 September 2022.

- ^ Nataraj, Poornima (7 January 2013). "After 7 years, Mestripalya Lake may see a fresh lease of life". Deccan Herald. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- ^ Yajaman, Arathi Manay (14 July 2013). "Munnekolala Lake restoration progresses". Citizen Matters, Blogs. Retrieved 16 September 2022.

- ^ a b "Preparation of Rejuvenation Plans for 5 lakes, Bengaluru, India" (PDF). Consortium for DEWATS Dissemination Society. p. 5. Retrieved 14 December 2022.

- ^ "Eco-Restoration of Wetlands, Navagara Lake, Bengaluru, Karnataka" (PDF). Consortium for DEWATS Dissemination Society, Bangalore. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ "Purified water to rid Nayandahalli lake of contamination". The Hans India. 9 June 2022. Retrieved 14 December 2022.

- ^ Centre for Lake Conservation (EMPRI), Inventorisation of Water Bodies in Bengaluru Metropolitan Area II.2 2018, p. 1078.

- ^ Staff Reporter (26 January 2019). "Yelahanka's Puttenahalli lake to be rejuvenated soon". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ Centre for Lake Conservation (EMPRI), Inventorisation of Water Bodies in Bengaluru Metropolitan Area II.2 2018, p. 1084.

- ^ "Sarakki lake brims with water, regains lost glory". The New Indian Express. 3 June 2019. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ Thakur, Aksheev (11 September 2022). "Lakes of Bengaluru: Here's why Saul Kere overflowed and inundated areas around it". The Indian Express. Retrieved 17 September 2022.

- ^ Thakur, Aksheev (10 July 2022). "Lakes of Bengaluru: Snail-paced restoration work of Seegehalli Lake a concern, BBMP blames cash crunch". The Indian Express. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ "Dying Seetharampalya lake gets a new lease of life". Deccan Herald. 4 June 2015. Retrieved 17 September 2022.

- ^ Correspondent, Special (15 July 2022). "Locals oppose changing name of Singapura lake in Bengaluru". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 16 December 2022.

{{cite news}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ Sayeed, Vikhar Ahmed (10 July 2022). "Where are Bengaluru's lakes?". Frontline. The Hindu. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ Thakur, Aksheev (4 December 2022). "Lakes of Bengaluru: Once revived, Talaghattapura lake yearns for maintenance". The Indian Express. Retrieved 16 December 2022.

- ^ Centre for Lake Conservation (EMPRI), Inventorisation of Water Bodies in Bengaluru Metropolitan Area II.4 2018, p. 1000.

- ^ Parashar, Kiran (12 December 2021). "In the name of 'development', Bengaluru's Ullal Lake is now a stinking bed of sewage". The Indian Express. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ Bhardwaj, Meera (2 June 2017). "Uttarahalli lake brims with water, new hope". The New Indian Express. Retrieved 16 September 2022.

- ^ "Vibhutipura Lake gets a fresh lease of life". Deccan Herald. 7 April 2014. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ "BDA biggest encroacher in Bengaluru". Deccan Herald. 8 January 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2022.

- ^ Nagendra 2016, p. 169, Chapter 9.

- ^ Nathan, Archana (11 July 2012). "Round of golf on a lakebed". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 20 September 2022.

- ^ Patrao, Michael (2 June 2013). "Legendary playgrounds". Deccan Herald. Retrieved 23 September 2022.

- ^ Kumar, Shivali (26 September 2012). "Facilities galore". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 23 September 2022.

- ^ G N, Prashanth (9 November 2014). "Dharmambudhi, from a water tank to a bus station". Deccan Herald. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- ^ "TERI building sits on Domlur lake: Former chief secy". Deccan Herald. 2 June 2015. Retrieved 20 September 2022.

- ^ Chandramouli, K. "City of forsaken lakes". Wetland News, Energy and Wetlands Research Group. Western Ghats Biodiversity Information System, Centre for Ecological Sciences (CES), Indian Institute of Science (IISc). Archived from the original on 8 April 2018. Published in The Hindu in 2002.

- ^ Staff Reporter (5 May 2015). "What will the elite in Dollars Colony do?". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 20 September 2022.

- ^ Mathew, Melvin (5 April 2022). "Remains of a lake". Bangalore Mirror. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ Parashar, Kiran (4 October 2021). "Concretisation of Storm Water Drains and encroachment of lakes leading to flooding in Bengaluru: CAG report". The Indian Express. Retrieved 16 September 2022.

- ^ "Most Bengaluru lakes encroached: NEERI report". The New Indian Express. 9 November 2019. Retrieved 23 September 2022.

- ^ Nandakumar, Prathibha (6 February 2017). "Give us back our lakes". Bangalore Mirror. Retrieved 16 September 2022.

- ^ Menezes, Naveen (13 February 2021). "3 'disused lakes' can be restored, assures NEERI". Bangalore Mirror. Retrieved 6 November 2022.

- ^ Manjusainath, G (29 August 2014). "10 of 63 City lakes exist only on paper". Deccan Herald. Retrieved 6 November 2022.

- ^ "Most Bengaluru lakes encroached: NEERI report". The New Indian Express. 9 November 2019. Retrieved 6 November 2022.

- ^ Shekhar, Divya (27 September 2018). "How Millers tank breach helps us understand recent flooding in Bengaluru". The Economic Times. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- ^ Thippaiah 2009, p. 8.

- ^ a b "Lost lakes, encroached drains: Why some parts of Bengaluru flooded worse than others". The News Minute. 21 October 2017. Retrieved 23 September 2022.

- ^ "Once upon a Lake". Bangalore Mirror. 25 May 2022. Retrieved 16 September 2022.

- ^ HS, Shreyas (30 June 2022). "19 Bengaluru lakes in disuse, can't be reclaimed: Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike". The Times of India. Retrieved 23 September 2022.

- ^ "Probe lake breaches, prevent them in future, HC tells Karnataka". The New Indian Express. 28 November 2019. Retrieved 23 September 2022.

- ^ Shekhar, Divya (14 May 2015). "Shoolay junction was once home to a lake and flowering greens". The Economic Times. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- ^ Joseph, Krupa (4 November 2020). "What explains Bengaluru floods?". Deccan Herald. Retrieved 6 November 2022.

- ^ Krishnamurthy, Sukanya (2012). Reading Architecture - Remembering - Forgetting interplay: Development of a Framework to Study Urban and Object Level Cases (Thesis). Bauhaus-Universität Weimar. doi:10.25643/bauhaus-universitaet.1802. p 130

- ^ "BDA engineers admit to goofing up on lake". Deccan Herald. 14 June 2013. Retrieved 23 September 2022.

- ^ Manjusainath, G (15 February 2015). "Cheated on a lakebed". Deccan Herald. Retrieved 23 September 2022.

- ^ "District admin to take over Venkatarayana kere". Deccan Herald. 6 October 2014. Retrieved 23 September 2022.

- ^ BP, Darshan Devaiah (5 December 2021). "Hesaraghatta Lake: From a drinking water source of Bengaluru to a haven for sand mining, open defecation". The Indian Express. Retrieved 17 September 2022.

- ^ Thakur, Aksheev (29 January 2022). "Bengaluru: Industrial waste, sewage and encroachments take a heavy toll on Muthanallur lake". The Indian Express. Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- Works cited

- Chakrapani, B. K.; Desai, Milind; George, Joseph; Karthikeyan, S.; Krishna, M. B.; Kumar, U. Harish; Naveein, O. C.; Sridhar, S.; Srinivasa, T. S.; N., Srinivasan; S., Subramanya (1990). Survey of Irrigation Tanks as Wetland Bird Habitats in the Bangalore area, India, January 1989. Birdwatchers' Field Club of Bangalore.

- Srinivas, Smriti (2001). Landscapes of Urban Memory. The Sacred and the Civic in India's High-Tech City. Globalization and Community. Vol. 9. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0-8166-3616-8.

- Shah, Esha (2003). Social Designs: Tank Irrigation Technology and Agrarian Transformation in Karnataka, South India. Thesis published by Orient Longman as a part of Wageningen University Water Resources Series. ISBN 90-5808-827-8 – via Wageningen University.

- Thippaiah, P (2009), Vanishing Lakes: A Study of Bangalore City (PDF), Social and Economic Change Monograph Series 17, Institute for Social and Economic Change, Bangalore, ISBN 978-81-7791-116-9

- Nagendra, Harini (2016). Nature in the City: Bengaluru in the Past, Present, and Future. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-908968-0.

- Final Report on Inventorisation of Water Bodies in Bengaluru Metropolitan Area (BMA), vol. 1, Karnataka Lake Conservation and Development Authority (KLCDA), Centre for Lake Conservation (CLC), Environmental Management and Policy Research Institute (EMPRI) (Department of Forest, Ecology and Environment, Government of Karnataka), March 2018

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: others (link). Accessed via Environment Support Group- Volume-II: Lake Database and Atlas (Part-2: Bengaluru East Taluk)

- Volume-II: Lake Database and Atlas (Part-4: Bengaluru South Taluk)

- Mani, A. (1985). "A Study of the Climate of Bangalore". Essays on Bangalore (PDF). Vol. 2. Convenors Vinod Vyasulu and Amulya Kumar N. Reddy. Karnataka State Council for Science and Technology.

- Subramanian, D. K. (1985). "Bangalore City's Water Supply - A Study and Analysis". Essays on Bangalore (PDF). Vol. 4. Convenors Vinod Vyasulu and Amulya Kumar N. Reddy. Karnataka State Council for Science and Technology.

Further reading

[edit]- Nair, Janaki (2005). The Promise of the Metropolis: Bangalore's Twentieth Century. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-566725-7.

- Nath, Sanchayan (2021). "Managerial, clientelist or populist? Lake governance in the Indian city of Bangalore". Water International. 46 (4). Routledge, Taylor & Francis: 524–542. Bibcode:2021WatIn..46..524N. doi:10.1080/02508060.2021.1926827. ISSN 0250-8060. S2CID 235769625.

- Ramesh, Aditya (2021). "Flows and fixes: water, disease and housing in Bangalore, 1860–1915". Urban History: 1–23. doi:10.1017/S0963926821000705. ISSN 0963-9268. S2CID 244003581.

- Gouri, R L; Srinivas, V V (2015). "Reliability Assessment of a Storm Water Drain Network". Aquatic Procedia. 4. Elsevier: 772–779. Bibcode:2015AqPro...4..772G. doi:10.1016/j.aqpro.2015.02.160.

- K, Chandrakanth (March 2018). "Ecological Impact of Urban Development: Lakes of Bengaluru". Tekton. 5 (1): 22–45.

- Sundaresan, Jayaraj (2011). "Planning as Commoning: Transformation of a Bangalore Lake". Economic and Political Weekly. 46 (50): 71–79. ISSN 0012-9976. JSTOR 41319486.

- Yashas, V; Aman, Bagrecha; Dhanush, S (1 March 2021). "Feasibility study of floating solar panels over lakes in Bengaluru City, India". Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers - Smart Infrastructure and Construction. 174 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1680/jsmic.21.00002a. ISSN 2397-8759.

- Paul, Jai M. (2014). "Modelling of Lake Water Balance and Ground Water Surface Water Interaction Using Remote Sensing Gis and Isotope Techniques". Bangalore University. hdl:10603/347116 – via Shodhganga.

- Preservation of Lakes in the City of Bangalore. Report of the Committee constituted by the Hon'ble High Court of Karnataka to examine the ground realities and prepare an action plan for preservation of lakes in the City of Bangalore. (PDF), karunadu.karnataka.gov.in Official Website of Government of Karnataka, 2011

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Brownstein, Daniel (1 March 2021). "Bangalore's Disappearing Lakes". Guerrilla Cartography.

- Palanichamy, Raj Bhagat (7 September 2022). "Overpopulation, concrete jungle, altered landscape: Decoding Bengaluru's urban flood woes". India Today.

- Kulranjan, Rashmi; Palur, Shashank (7 March 2022). "Crowdmapping Bengaluru's Vanishing Lakes". IndiaSpend.

External links

[edit]- Geospatial Data for Bengaluru Urban/Rural via Karnataka State Remote Sensing Applications Centre

- 167 Lakes in BBMP Custody via official website of the Lakes Department of BBMP

- Rajakaluve Encroachment Finder www

.rajakaluve .org - Karnataka land records (Digital Maps of Lakes) (Survey Maps of Lakes)

- Once There Was a Lake

- topographic-map.com