Society of Dilettanti

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (August 2017) |

The Society of Dilettanti (founded 1734) is a British society of noblemen and scholars that sponsored the study of ancient Greek and Roman art, and the creation of new work in the style.

History

[edit]Though the exact date is unknown, the Society is believed to have been established as a gentlemen's club in 1734 [2] by a group of people who had been on the Grand Tour. Records of the earliest meeting of the society were written somewhat informally on loose pieces of paper. The first entry in the first minute book of the society is dated 5 April 1736.[3] For a number of years it held its meetings at the Thatched House Tavern in St James's.

In 1743, Horace Walpole condemned its affectations and described it as "... a club, for which the nominal qualification is having been in Italy, and the real one, being drunk: the two chiefs are Lord Middlesex and Sir Francis Dashwood, who were seldom sober the whole time they were in Italy."[4]

The group, initially led by Francis Dashwood, contained several dukes and was later joined by Joshua Reynolds, David Garrick, Uvedale Price, and Richard Payne Knight, among others. It was closely associated with Brooks's, one of London's most exclusive gentlemen's clubs. The society quickly became wealthy, through a system in which members made contributions to various funds to support building schemes and archaeological expeditions.

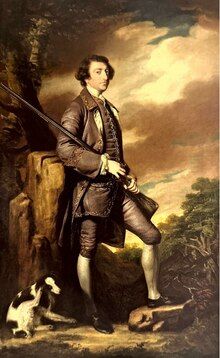

The first artist associated with the group was George Knapton.

The Society of Dilettanti aimed to correct and purify the public taste of the country; from the 1740s, it began to support Italian opera. A few years before Joshua Reynolds became a member, the group worked towards the objective of forming a public academy, and from the 1750s, it was the prime mover in establishing the Royal Academy of Arts. In 1775, the club had accumulated enough money towards a scholarship fund for the purpose of supporting a student's travel to Rome and Greece, or for archaeological expeditions such as that of Richard Chandler, William Pars, and Nicholas Revett, the results of which they published in Ionian Antiquities, a major influence on neoclassicism in Britain.

Among the publications published at the expense of the society was The bronzes of Siris (London, 1836) by Danish archaeologist Peter Oluf Bronsted.[5]

Membership

[edit]The society has 60 members, elected by secret ballot. An induction ceremony is held at Brooks's, an exclusive London gentleman's club. It makes annual donations to the British Schools in Rome and Athens, and a separate fund set up in 1984 provides financial assistance for visits to classical sites and museums.

Notable members

[edit]

- Thomas Anson (founder member)

- Right Honourable Sir Joseph Banks

- George Beaumont

- Rev. Clayton Mordaunt Cracherode

- Anthony Morris Storer, Esq.[8]

- Charles Crowle, Esq.

- Henry Dawkins of Standlynch Hall, Wiltshire

- Francis Dashwood, 11th Baron le Despencer (founder member)

- Lord Dundas

- Sir Henry Englefield

- Stephen Payne-Gallwey, Esq.

- David Garrick

- Philip Eyre Gell (from 1748)

- Major General Claude Martin

- Sir James Gray, 2nd Baronet (founder member)

- Sir George Gray, 3rd Baronet (founder member)

- The Honourable Charles Francis Greville

- Sir William Hamilton (diplomat)

- Thomas Hope

- Philip Metcalfe (from 1786)

- Richard Payne Knight (from 1781)

- Duke of Leeds

- Constantin John Lord Murlgrave

- Uvedale Price

- Sir Joshua Reynolds (from 1766)

- Lord Seaforth

- John Spencer, 1st Earl Spencer

- Spencer Stanhope, Esq.

- Sir John Taylor, 1st Baronet

- Richard Thompson, Esq.

- Sir Anthony R. Wagner, Garter Principal King of Arms

- William Wilkins

- Sir Watkin Williams-Wynn, 4th Baronet

- Charles Williams-Wynn (the elder)

- Sir Charles Williams-Wynn (the younger)

- Charles Towneley, antiquary and collector

References and sources

[edit]- References

- ^ "'The Dilettanti Society' – National Portrait Gallery". www.npg.org.uk. Retrieved 22 March 2023.

- ^ Jason M. The Society of Dilettanti: archaeology and identity in the British enlightenment. New Haven: Published for the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art by Yale University Press, 2009.

- ^ Cust, L; Colvin, S (1914). "Antiquity of the Society". History of the Society of Dilettanti. London: Macmillan and Company, Ltd. pp. 1–21.

- ^ Horace Walpole, quoted in Jeremy Black, The British and the Grand Tour (1985), p. 120.

- ^ The National Cyclopaedia of Useful Knowledge, Vol.III, London, 1847, Charles Knight, p. 847.

- ^ "'The Dilettanti Society' – National Portrait Gallery". npg.org.uk. Retrieved 27 March 2023.

- ^ "Grecian Taste and Roman Spirit: The Society of Dilettanti". Getty Villa Exhibitions. J. Paul Getty Trust. 2008. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- ^ Dictionary of National Biography, Volume 22 Page 1243

- Sources

- The Penguin Dictionary of British and Irish History, editor: Juliet Gardiner

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Wood, James, ed. (1907). The Nuttall Encyclopædia. London and New York: Frederick Warne.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - This article incorporates text from:The Life of Sir Joshua Reynolds, Volume 2, James Northcote, 1819

- Members of the Society of Dilettanti, 1736–1874, edited by Sir William Frazer. Chiswick Press.

Further reading

[edit]- Dorment, Richard. The Dilettanti: exclusive society that celebrates art (Daily Telegraph 2 September 2008)

- Harcourt-Smith, Sir Cecil and George Augustin Macmillan, The Society of Dilettanti: Its Regalia and Pictures (London: Macmillan, 1932).

- Kelly, Jason M., The Society of Dilettanti: Archaeology and Identity in the British Enlightenment (New Haven and London: Yale University Press and the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, 2009).

- Redford, Bruce, Dilettanti: The Antic and the Antique in Eighteenth-century England (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2008).

- Robinson, Terry F., "Eighteenth-Century Connoisseurship and the Female Body" Oxford Handbooks Online. Oxford University Press. Web. 10 May 2017.

- Simon, Robin, "Reynolds and the Double-entendre: the Society of Dilettanti Portraits", The British Art Journal 3, no. 1 (2001): 69–77.

- West, Shearer, "Libertinism and the Ideology of Male Friendship in the Portraits of the Society of Dilettanti", Eighteenth Century Life 16 (1992): 76–104.

External links

[edit]- Review of Bruce Redford, Dilettanti: The Antic and the Antique in Eighteenth-Century England. in Bryn Mawr Classical Review 2008.08.28

- "Gentlemen Did Not Dig", by Rosemary Hill, review of The Society of Dilettanti: Archaeology and Identity in the British Enlightenment, by Jason Kelly (Yale, 366 pp., January 2010, ISBN 978 0 300 15219 7). London Review of Books, Vol. 32 No. 12 · 24 June 2010

- Antiquities of Ionia (Part 1 of 3) Kenneth Franzheim II Rare Books Room, William R. Jenkins Architecture and Art Library, University of Houston Digital Library.