John Diefenbaker

John Diefenbaker | |

|---|---|

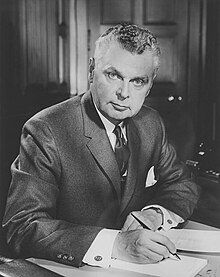

Diefenbaker in 1957 | |

| 13th Prime Minister of Canada | |

| In office June 21, 1957 – April 22, 1963 | |

| Monarch | Elizabeth II |

| Governors General | |

| Preceded by | Louis St. Laurent |

| Succeeded by | Lester B. Pearson |

| Leader of the Opposition | |

| In office April 22, 1963 – September 8, 1967 | |

| Preceded by | Lester B. Pearson |

| Succeeded by | Michael Starr |

| In office December 14, 1956 – June 20, 1957 | |

| Preceded by | William Earl Rowe |

| Succeeded by | Louis St. Laurent |

| Leader of the Progressive Conservative Party of Canada | |

| In office December 14, 1956 – September 9, 1967 | |

| Preceded by | William Earl Rowe (interim) |

| Succeeded by | Robert Stanfield |

| Secretary of State for External Affairs | |

| In office June 21, 1957 – September 12, 1957 | |

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Preceded by | Lester B. Pearson |

| Succeeded by | Sidney Earle Smith |

| Member of Parliament for Prince Albert | |

| In office August 10, 1953 – August 16, 1979 | |

| Preceded by | Francis Helme |

| Succeeded by | Stan Hovdebo |

| Member of Parliament for Lake Centre | |

| In office March 26, 1940 – August 10, 1953 | |

| Preceded by | John Frederick Johnston |

| Succeeded by | Riding abolished |

| Personal details | |

| Born | John George Diefenbaker September 18, 1895 Neustadt, Ontario, Canada |

| Died | August 16, 1979 (aged 83) Ottawa, Ontario, Canada |

| Resting place | Outside Diefenbaker Canada Centre, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan |

| Political party | Progressive Conservative |

| Spouses | |

| Alma mater | University of Saskatchewan (BA, MA, LLB) |

| Occupation |

|

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | Canada |

| Branch/service | Canadian Expeditionary Force |

| Years of service | 1916–1917 |

| Rank | Lieutenant |

| Unit | 196th Battalion |

| Battles/wars | World War I |

John George Diefenbaker (/ˈdiːfənbeɪkər/ DEE-fən-bay-kər; September 18, 1895 – August 16, 1979) was a Canadian politician who served as the 13th prime minister of Canada, from 1957 to 1963. He was the only Progressive Conservative[a] party leader between 1930 and 1979 to lead the party to an election victory, doing so three times, although only once with a majority of the seats in the House of Commons.

Diefenbaker was born in the small town of Neustadt in Southwestern Ontario. In 1903, his family migrated west to the portion of the North-West Territories that would soon become the province of Saskatchewan. He grew up in the province and was interested in politics from a young age. After service in World War I, Diefenbaker became a noted criminal defence lawyer. He contested elections through the 1920s and 1930s with little success until he was finally elected to the House of Commons in 1940.

Diefenbaker was repeatedly a candidate for the party leadership. He gained that position in 1956, on his third attempt. In 1957, he led the party to its first electoral victory in 27 years; a year later he called a snap election and spearheaded them to one of their greatest triumphs. Diefenbaker appointed the first female minister in Canadian history to his cabinet (Ellen Fairclough), as well as the first Indigenous member of the Senate (James Gladstone). During his six years as prime minister, his government obtained passage of the Canadian Bill of Rights and granted the vote to the First Nations and Inuit peoples. In 1962, Diefenbaker's government eliminated racial discrimination in immigration policy. In foreign policy, his stance against apartheid helped secure the departure of South Africa from the Commonwealth of Nations, but his indecision on whether to accept Bomarc nuclear missiles from the United States led to his government's downfall. Diefenbaker is also remembered for his role in the 1959 cancellation of the Avro Arrow project.

In the 1962 federal election, the Progressive Conservatives narrowly won a minority government before losing power altogether in 1963. Diefenbaker stayed on as party leader, becoming Opposition leader, but his second loss at the polls prompted opponents within the party to force him to a leadership convention in 1967. Diefenbaker stood for re-election as party leader at the last moment, but attracted only minimal support and withdrew. He remained in parliament until his death in 1979, two months after Joe Clark became the first Progressive Conservative prime minister since Diefenbaker. Diefenbaker ranks average in rankings of prime ministers of Canada.

Early life

[edit]

Diefenbaker was born on September 18, 1895, in Neustadt, Ontario, to William Thomas Diefenbaker and Mary Florence Diefenbaker, née Bannerman.[1] His father was the son of German immigrants from Adersbach (near Sinsheim) in Baden; Mary Diefenbaker was of Scottish descent and Diefenbaker was Baptist.[b] The family moved to several locations in Ontario in John's early years.[1] William Diefenbaker was a teacher, and had deep interests in history and politics, which he sought to inculcate in his students. He had remarkable success doing so; of the 28 students at his school near Toronto in 1903, four, including his son, John, served as Conservative MPs in the 19th Canadian Parliament beginning in 1940[2] (the others were Robert Henry McGregor, Joseph Henry Harris, and George Tustin).

The Diefenbaker family moved west in 1903, for William Diefenbaker to accept a position near Fort Carlton, then in the Northwest Territories (now in Saskatchewan).[3] In 1906, William claimed a quarter-section, 160 acres (0.65 km2) of undeveloped land near Borden, Saskatchewan.[4] In February 1910, the Diefenbaker family moved to Saskatoon, the site of the University of Saskatchewan. William and Mary Diefenbaker felt that John and his brother Elmer would have greater educational opportunities in Saskatoon.[5]

John Diefenbaker had been interested in politics from an early age and told his mother at the age of eight or nine that he would some day be prime minister. She told him that it was an impossible ambition, especially for a boy living on the prairies.[c] She would live to be proved wrong.[c] John claimed that his first contact with politics came in 1910, when he sold a newspaper to Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier, in Saskatoon to lay the cornerstone for the university's first building. The present and future prime ministers conversed, and when giving his speech that afternoon, Laurier mentioned the newsboy, who had ended their conversation by saying, "I can't waste any more time on you, Prime Minister. I must get about my work."[5][d] The authenticity of the meeting was questioned in the 21st century, with an author suggesting that it was invented by Diefenbaker during an election campaign.[6][7]

In a 1977 interview with the CBC, Diefenbaker recalled he saw injustice first-hand in his youth against French Canadians, Indigenous Canadians and the Métis. He said, "From my earliest days, I knew the meaning of discrimination. Many Canadians were virtually second-hand citizens because of their names and racial origin. Indeed, it seemed until the end of World War II that the only first-class Canadians were either of English or French descent. As a youth, l determined to devote myself to assuring that all Canadians, whatever their racial origin, were equal and declared myself to be a sworn enemy of discrimination."[8][9]

After graduating from high school in Saskatoon in 1912, Diefenbaker entered the University of Saskatchewan.[10] He received his Bachelor of Arts degree in 1915, and his Master of Arts the following year.[11]

Diefenbaker was commissioned a lieutenant into the 196th (Western Universities) Battalion, CEF,[12][13] in May 1916. In September of that year, Diefenbaker was part of a contingent of 300 junior officers sent to Britain for pre-deployment training. Diefenbaker related in his memoirs that he was hit by a shovel, and the injury eventually resulted in him being sent home as an invalid. Diefenbaker's recollections do not correspond with his army medical records, which show no contemporary account of such an injury, and his biographer, Denis Smith, speculates that any injury was psychosomatic.[14]

After leaving the military in 1917,[13] Diefenbaker returned to Saskatchewan where he resumed his work as an articling student in law. He received his law degree in 1919,[15] the first student to secure three degrees from the University of Saskatchewan.[16] On June 30, 1919, he was called to the bar, and the following day, opened a small practice in the village of Wakaw, Saskatchewan.[15]

Barrister and candidate (1919–1940)

[edit]Wakaw days (1919–1924)

[edit]

Although Wakaw had a population of only 400, it sat at the heart of a densely populated area of rural townships and had its own district court. It was also easily accessible to Saskatoon, Prince Albert and Humboldt, places where the Court of King's Bench sat. The local people were mostly immigrants, and Diefenbaker's research found them to be particularly litigious. There was already one barrister in town, and the residents were loyal to him, initially refusing to rent office space to Diefenbaker. The new lawyer was forced to rent a vacant lot and erect a two-room wooden shack.[17]

Diefenbaker won the local people over through his success; in his first year in practice, he tried 62 jury trials, winning approximately half of his cases. He rarely called defence witnesses, thereby avoiding the possibility of rebuttal witnesses for the Crown, and securing the last word for himself.[18] In late 1920, he was elected to the village council to serve a three-year term.[19]

Diefenbaker would often spend weekends with his parents in Saskatoon. While there, he began to woo Olive Freeman, daughter of the Baptist minister, but in 1921, she moved with her family to Brandon, Manitoba, and the two lost touch for more than 20 years. He then courted Beth Newell, a cashier in Saskatoon, and by 1922, the two were engaged. However, in 1923, Newell was diagnosed with tuberculosis, and Diefenbaker broke off contact with her. She died the following year. Diefenbaker was himself subject to internal bleeding, and may have feared that the disease would be transmitted to him. In late 1923, he had an operation at the Mayo Clinic for a gastric ulcer, but his health remained uncertain for several more years.[20]

After four years in Wakaw, Diefenbaker so dominated the local legal practice that his competitor left town. On May 1, 1924, Diefenbaker moved to Prince Albert, leaving a law partner in charge of the Wakaw office.[21]

Aspiring politician (1924–1929)

[edit]Since 1905, when Saskatchewan entered Confederation, the province had been dominated by the Liberal Party, which practised highly effective machine politics. Diefenbaker was fond of stating, in his later years, that the only protection a Conservative had in the province was that afforded by the game laws.[22]

Diefenbaker's father, William, was a Liberal; however, John Diefenbaker found himself attracted to the Conservative Party. Free trade was widely popular throughout Western Canada, but Diefenbaker was convinced by the Conservative position that free trade would make Canada an economic dependent of the United States.[23] However, he did not speak publicly of his politics. Diefenbaker recalled in his memoirs that, in 1921, he had been elected as secretary of the Wakaw Liberal Association while absent in Saskatoon, and had returned to find the association's records in his office. He promptly returned them to the association president. Diefenbaker also stated that he had been told that if he became a Liberal candidate, "there was no position in the province which would not be open to him."[24]

It was not until 1925 that Diefenbaker publicly came forward as a Conservative, a year in which both federal and Saskatchewan provincial elections were held. Journalist Peter C. Newman, in his best-selling account of the Diefenbaker years, suggested that this choice was made for practical, rather than political reasons, as Diefenbaker had little chance of defeating established politicians and securing the Liberal nomination for either the House of Commons or the Legislative Assembly.[25] The provincial election took place in early June; Liberals would later claim that Diefenbaker had campaigned for their party in the election. On June 19, however, Diefenbaker addressed a Conservative organizing committee, and on August 6, was nominated as the party's candidate for the federal riding of Prince Albert, a district in which the party's last candidate had lost his election deposit. A nasty campaign ensued, in which Diefenbaker was called a "Hun" because of his German-derived surname. The 1925 federal election was held on October 29; he finished third behind the Liberal and Progressive Party candidates, losing his deposit.[26]

The winning candidate, Charles McDonald, did not hold the seat long, resigning it to open a place for the Prime Minister, William Lyon Mackenzie King, who had been defeated in his Ontario riding. The Tories ran no candidate against King in the by-election on February 15, 1926, and he won easily. Although in the 1925 federal election, the Conservatives had won the greatest number of seats, King continued as prime minister with the support of the Progressives. Mackenzie King held office for several months until he finally resigned when the Governor General, Lord Byng, refused a dissolution. Conservative Party leader Arthur Meighen became prime minister, but was quickly defeated in the House of Commons, and Byng finally granted a dissolution of Parliament. Diefenbaker, who had been confirmed as Conservative candidate, stood against King in the 1926 election, a rare direct electoral contest between two individuals who had or would become prime minister. King triumphed easily over Diefenbaker, the Liberals won the federal election, and King regained his position as prime minister.[27]

Perennial candidate (1929–1940)

[edit]

Diefenbaker stood for the Legislative Assembly in the 1929 provincial election. He was defeated,[28] but Saskatchewan Conservatives formed their first government, with help from smaller parties. As the defeated Conservative candidate for Prince Albert City, he was given charge of political patronage there and was created a King's Counsel.[29] Three weeks after his electoral defeat, he married Saskatoon teacher Edna Brower.[30]

Diefenbaker chose not to stand for the House of Commons in the 1930 federal election, citing health reasons. The Conservatives gained a majority in the election, and party leader R. B. Bennett became prime minister.[29] Diefenbaker continued a high-profile legal practice, and in 1933, ran for mayor of Prince Albert. He was defeated by 48 votes in an election in which over 2,000 ballots were cast.[e]

In 1934, when the Crown prosecutor for Prince Albert resigned to become the Conservative Party's legislative candidate, Diefenbaker took his place as prosecutor. Diefenbaker did not stand in the 1934 provincial election, in which the governing Conservatives lost every seat. Six days after the election, Diefenbaker resigned as Crown prosecutor.[31] The federal government of Bennett was defeated the following year and Mackenzie King returned as prime minister. Judging his prospects hopeless, Diefenbaker had declined a nomination to stand again against Mackenzie King in Prince Albert. In the waning days of the Bennett government, the Saskatchewan Conservative Party president was appointed a judge, leaving Diefenbaker, who had been elected the party's vice president, as acting president of the provincial party.[32]

Saskatchewan Conservatives eventually arranged a leadership convention for October 28, 1936. Eleven people were nominated, including Diefenbaker. The other ten candidates withdrew, and Diefenbaker won the position by default. Diefenbaker asked the federal party for $10,000 in financial support, but the funds were refused, and the Conservatives were shut out of the legislature in the 1938 provincial elections for the second consecutive time. Diefenbaker himself was defeated in the Arm River riding by 190 votes.[33] With the province-wide Conservative vote having fallen to 12 percent, Diefenbaker offered his resignation to a post-election party meeting in Moose Jaw, but it was refused. Diefenbaker continued to run the provincial party out of his law office and paid the party's debts from his own pocket.[34]

Diefenbaker quietly sought the Conservative nomination for the federal riding of Lake Centre but was unwilling to risk a divisive intra-party squabble. In what Diefenbaker biographer Smith states "appears to have been an elaborate and prearranged charade", Diefenbaker attended the nominating convention as keynote speaker, but withdrew when his name was proposed, stating a local man should be selected. The winner among the six remaining candidates, riding president W. B. Kelly, declined the nomination, urging the delegates to select Diefenbaker, which they promptly did.[35] Mackenzie King called a general election for March 25, 1940.[36] The incumbent in Lake Centre was Liberal John Frederick Johnston. Diefenbaker campaigned aggressively in Lake Centre, holding 63 rallies and seeking to appeal to members of all parties. On election day, he defeated Johnston by 280 votes on what was otherwise a disastrous day for the Conservatives, who won only 39 seats out of the 245 in the House of Commons—their lowest total since Confederation.[36]

Parliamentary rise (1940–1957)

[edit]Mackenzie King years (1940–1948)

[edit]Diefenbaker joined a shrunken and demoralized Conservative caucus in the House of Commons. The Conservative leader, Robert Manion, failed to win a place in the Commons in the election, which saw the Liberals take 181 seats.[37] The Tories sought to be included in a wartime coalition government, but Mackenzie King refused. The House of Commons had only a slight role in the war effort; under the state of emergency, most business was accomplished through the Cabinet issuing Orders in Council.[38]

Diefenbaker was appointed to the House Committee on the Defence of Canada Regulations, an all-party committee which examined the wartime rules which allowed arrest and detention without trial. On June 13, 1940, Diefenbaker made his maiden speech in the House of Commons, supporting the regulations, and emphatically stating that most Canadians of German descent were loyal.[39] In his memoirs, Diefenbaker wrote he waged an unsuccessful fight against the forced relocation and internment of many Japanese-Canadians, but historians say that the fight against the internment never took place.[40][41]

According to Diefenbaker's biographer, Denis Smith, the Conservative MP quietly admired Mackenzie King for his political skills.[42] However, Diefenbaker proved a gadfly and an annoyance to Mackenzie King. Angered by the words of Diefenbaker and fellow Conservative MP Howard Green in seeking to censure the government, the Prime Minister referred to Conservative MPs as "a mob".[42] When Diefenbaker accompanied two other Conservative leaders to a briefing by Mackenzie King on the war, the Prime Minister exploded at Diefenbaker (a constituent of his), "What business do you have to be here? You strike me to the heart every time you speak."[42]

The Conservatives elected a floor leader, and in 1941 approached former prime minister Meighen, who had been appointed as a senator by Bennett, about becoming party leader again. Meighen agreed, and resigned his Senate seat, but lost a by-election for an Ontario seat in the House of Commons.[43] He remained as leader for several months, although he could not enter the chamber of the House of Commons. Meighen sought to move the Tories to the left, in order to undercut the Liberals and to take support away from the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF, the predecessor of the New Democratic Party (NDP)). To that end, he sought to draft the Liberal-Progressive premier of Manitoba, John Bracken, to lead the Conservatives. Diefenbaker objected to what he saw as an attempt to rig the party's choice of new leader[44] and stood for the leadership himself at the party's 1942 leadership convention.[45] Bracken was elected on the second ballot; Diefenbaker finished a distant third in both polls. At Bracken's request, the convention changed the party's name to "Progressive Conservative Party of Canada."[46] Bracken chose not to seek entry to the House through a by-election, and when the Conservatives elected a new floor leader, Diefenbaker was defeated by one vote.[47]

Bracken was elected to the Commons in the 1945 general election, and for the first time in five years the Tories had their party leader in the House of Commons. The Progressive Conservatives won 67 seats to the Liberals' 125, with smaller parties and independents winning 52 seats. Diefenbaker increased his majority to over 1,000 votes, and had the satisfaction of seeing Mackenzie King defeated in Prince Albert—albeit by a CCF candidate. The Prime Minister was returned in an Ontario by-election within months.[48]

Diefenbaker staked out a position on the populist left of the PC party. Though most Canadians were content to look to Parliament for protection of civil liberties, Diefenbaker called for a Bill of Rights, calling it "the only way to stop the march on the part of the government towards arbitrary power".[41] He objected to the great powers used by the Mackenzie King government to attempt to root out Soviet spies after the war, such as imprisonment without trial, and complained about the government's proclivity for letting its wartime powers become permanent.[41]

Leadership contender (1948–1956)

[edit]

In early 1948, Mackenzie King, now aged 73, announced his retirement; later that year Louis St. Laurent succeeded him. Although Bracken had nearly doubled the Tory representation in the House, prominent Tories were increasingly unhappy with his leadership and pressured him to stand down. These party bosses believed that Ontario Premier George A. Drew, who had won three successive provincial elections and had even made inroads in francophone ridings, was the man to lead the Progressive Conservatives to victory. When Bracken resigned on July 17, 1948, Diefenbaker announced his candidacy. The party's backers, principally financiers headquartered on Toronto's Bay Street, preferred Drew's conservative political stances to Diefenbaker's Western populism.[49] Tory leaders packed the 1948 leadership convention in Ottawa in favour of Drew, appointing more than 300 delegates at-large. One cynical party member commented, "Ghost delegates with ghost ballots, marked by the ghostly hidden hand of Bay Street, are going to pick George Drew, and he'll deliver a ghost-written speech that'll cheer us all up, as we march briskly into a political graveyard."[50] Drew easily defeated Diefenbaker on the first ballot. St. Laurent called an election for June 1949, and the Tories were decimated, falling to 41 seats, only two more than the party's 1940 nadir.[51] Despite intense efforts to make the Progressive Conservatives appeal to Quebecers, the party won only two seats in the province.[52]

Newman argued that but for Diefenbaker's many defeats, he would never have become prime minister:

If, as a neophyte lawyer, he had succeeded in winning the Prince Albert seat in the federal elections of 1925 or 1926, ... Diefenbaker would probably have been remembered only as an obscure minister in Bennett's Depression cabinet ... If he had carried his home-town mayoralty in 1933, ... he'd probably not be remembered at all ... If he had succeeded in his bid for the national leadership in 1942, he might have taken the place of John Bracken on his six-year march to oblivion as leader of a party that had not changed itself enough to follow a Prairie radical ... [If he had defeated Drew in 1948, he] would have been free to flounder before the political strength of Louis St. Laurent in the 1949 and 1953 campaigns.[53]

The governing Liberals repeatedly attempted to draw Diefenbaker's seat out from under him. In 1948, Lake Centre was redistricted to remove areas which strongly supported Diefenbaker. In spite of that, he was returned in the 1949 election, the only PC member from Saskatchewan. In 1952, a redistricting committee dominated by Liberals abolished Lake Centre entirely, dividing its voters among three other ridings.[51] Diefenbaker stated in his memoirs that he had considered retiring from the House; with Drew only a year older than he was, the Westerner saw little prospect of advancement and had received tempting offers from Ontario law firms. However, the gerrymandering so angered him that he decided to fight for a seat.[54] Diefenbaker's party had taken Prince Albert only once, in 1911, but he decided to stand in that riding for the 1953 election and was successful.[51] He would hold that seat for the rest of his life.[55] Even though Diefenbaker campaigned nationally for party candidates, the Progressive Conservatives gained little, rising to 51 seats as St. Laurent led the Liberals to a fifth successive majority.[56] In addition to trying to secure his departure from Parliament, the government opened a home for unwed Indian mothers next door to Diefenbaker's home in Prince Albert.[51]

Diefenbaker continued practising law. In 1951, he gained national attention by accepting the Atherton case, in which a young telegraph operator had been accused of negligently causing a train crash by omitting crucial information from a message. Twenty-one people were killed, mostly Canadian troops bound for Korea. Diefenbaker paid $1,500 and sat a token bar examination to join the Law Society of British Columbia to take the case, and gained an acquittal, prejudicing the jury against the Crown prosecutor and pointing out a previous case in which interference had caused information to be lost in transmission.[57]

In the mid-1940s Edna began to suffer mental illness and was placed in a private psychiatric hospital for a time. She later fell ill from leukemia and died in 1951. In 1953, Diefenbaker married Olive Palmer (formerly Olive Freeman), whom he had courted while living in Wakaw. Olive Diefenbaker became a great source of strength to her husband. There were no children born of either marriage.[58] In 2013, claims were made that he fathered at least two sons out of wedlock, based a DNA test which, according to the test conductor, a 99.99% chance that the two individuals were related, with no other known commonality between them other than that Diefenbaker employed both mothers.[59]

Diefenbaker won Prince Albert in 1953, even as the Tories suffered a second consecutive disastrous defeat under Drew. Speculation arose in the press that the leader might be pressured to step aside. Drew was determined to remain, however, and Diefenbaker was careful to avoid any action that might be seen as disloyal. However, Diefenbaker was never a member of the "Five O'clock Club" of Drew intimates who met the leader in his office for a drink and gossip each day.[60][f] By 1955, there was a widespread feeling among Tories that Drew was not capable of leading the party to a victory. At the same time, the Liberals were in flux as the aging St. Laurent tired of politics.[61] Drew was able to damage the government in a weeks-long battle over the TransCanada pipeline in 1956—the so-called Pipeline Debate—in which the government, in a hurry to obtain financing for the pipeline, imposed closure before the debate even began. The Tories and the CCF combined to obstruct business in the House for weeks before the Liberals were finally able to pass the measure. Diefenbaker played a relatively minor role in the Pipeline Debate, speaking only once.[62]

Leader of the Opposition; 1957 election

[edit]By 1956, the Social Credit Party was becoming a potential rival to the Tories as Canada's main right-wing party.[63] Canadian journalist and author Bruce Hutchison discussed the state of the Tories in 1956:

When a party calling itself Conservative can think of nothing better than to outbid the Government's election promises; when it demands economy in one breath and increased spending in the next; when it proposes an immediate tax cut regardless of inflationary results ... when in short, the Conservative party no longer gives us a conservative alternative after twenty-one years ... then our political system desperately requires an opposition prepared to stand for something more than the improbable chance of quick victory.[64]

In August 1956, Drew fell ill and many within the party urged him to step aside, feeling that the Progressive Conservatives needed vigorous leadership with an election likely within a year. He resigned in late September, and Diefenbaker immediately announced his candidacy for the leadership.[65] A number of Progressive Conservative leaders, principally from the Ontario wing of the party, started a "Stop Diefenbaker" movement, and wooed University of Toronto president Sidney Smith as a possible candidate. When Smith declined,[66] they could find no one of comparable stature to stand against Diefenbaker. The only serious competition to Diefenbaker came from Donald Fleming, who had finished third at the previous leadership convention, but his having repeatedly criticised Drew's leadership ensured that the critical Ontario delegates would not back Fleming, all but destroying his chances of victory. At the leadership convention in Ottawa in December 1956, Diefenbaker won on the first ballot, and the dissidents reconciled themselves to his victory. After all, they reasoned, Diefenbaker was now 61 and unlikely to lead the party for more than one general election, an election they believed would be won by the Liberals regardless of who led the Tories.[65]

In January 1957, Diefenbaker took his place as Leader of the Official Opposition. In February, St. Laurent informed him that Parliament would be dissolved in April for an election on June 10. The Liberals submitted a budget in March; Diefenbaker attacked it for overly high taxes, failure to assist pensioners, and a lack of aid for the poorer provinces.[67] Parliament was dissolved on April 12.[68] St. Laurent was so confident of victory that he did not even bother to make recommendations to the Governor General to fill the 16 vacancies in the Senate.[69][70]

Diefenbaker ran on a platform which concentrated on changes in domestic policies. He pledged to work with the provinces to reform the Senate. He proposed a vigorous new agricultural policy, seeking to stabilize income for farmers. He sought to reduce dependence on trade with the United States, and to seek closer ties with the United Kingdom.[71] St. Laurent called the Tory platform "a mere cream-puff of a thing—with more air than substance".[72] Diefenbaker and the PC party used television adroitly, whereas St. Laurent stated that he was more interested in seeing people than in talking to cameras.[73] Though the Liberals outspent the Progressive Conservatives three to one, according to Newman, their campaign had little imagination, and was based on telling voters that their only real option was to re-elect St. Laurent.[70]

Diefenbaker characterized the Tory program in a nationwide telecast on April 30:

It is a program ... for a united Canada, for one Canada, for Canada first, in every aspect of our political and public life, for the welfare of the average man and woman. That is my approach to public affairs and has been throughout my life ... A Canada, united from Coast to Coast, wherein there will be freedom for the individual, freedom of enterprise and where there will be a Government which, in all its actions, will remain the servant and not the master of the people.[74]

The final Gallup poll before the election showed the Liberals ahead, 48% to 34%.[75] Just before the election, Maclean's magazine printed its regular weekly issue, to go on sale the morning after the vote, editorializing that democracy in Canada was still strong despite a sixth consecutive Liberal victory.[76] On election night, the Progressive Conservative advance started early, with the gain of two seats in reliably Liberal Newfoundland.[77] The party picked up nine seats in Nova Scotia, five in Quebec, 28 in Ontario, and at least one seat in every other province. The Progressive Conservatives took 112 seats to the Liberals' 105: a plurality, but not a majority.[g] While the Liberals finished some 200,000 votes ahead of the Tories nationally, that margin was mostly wasted in overwhelming victories in safe Quebec seats. St. Laurent could have attempted to form a government, however, with the minor parties pledging to cooperate with the Progressive Conservatives, he would have likely faced a quick defeat at the Commons.[78] St. Laurent instead resigned, making Diefenbaker prime minister.[79]

Prime Minister (1957–1963)

[edit]Domestic events and policies

[edit]Minority government

[edit]

When John Diefenbaker took office as Prime Minister of Canada on June 21, 1957, only one Progressive Conservative MP, Earl Rowe, had served in federal governmental office, for a brief period under Bennett in 1935. Rowe was no friend of Diefenbaker – he had briefly served as the party's acting leader in-between Drew's resignation and Diefenbaker's election, and did not definitively rule himself out of running to succeed Drew permanently until a relatively late stage, contributing to Diefenbaker's mistrust of him – and was given no place in his government.[80] Diefenbaker appointed Ellen Fairclough as Secretary of State for Canada, the first woman to be appointed to a Cabinet post, and Michael Starr as Minister of Labour, the first Canadian of Ukrainian descent to serve in Cabinet.[81]

As the Parliament buildings had been lent to the Universal Postal Union for its 14th congress, Diefenbaker was forced to wait until the fall to convene Parliament. However, the Cabinet approved measures that summer, including increased price supports for butter and turkeys, and raises for federal employees.[82] Once the 23rd Canadian Parliament was opened on October 14 by Queen Elizabeth II – the first to be opened by any Canadian monarch – the government rapidly passed legislation, including tax cuts and increases in old age pensions. The Liberals were ineffective in opposition, with the party in the midst of a leadership race after St. Laurent's resignation as party leader.[83]

With the Conservatives leading in the polls, Diefenbaker wanted a new election, hopeful that his party would gain a majority of seats. The strong Liberal presence meant that the Governor General could refuse a dissolution request early in a parliament's term and allow them to form government if Diefenbaker resigned. Diefenbaker sought a pretext for a new election.[84]

Such an excuse presented itself when former Secretary of State for External Affairs Lester Pearson attended his first parliamentary session as Leader of the Opposition on January 20, 1958, four days after becoming the Liberal leader. In his first speech as leader, Pearson (recently returned from Oslo where he had been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize), moved an amendment to supply, and called, not for an election, but for the Progressive Conservatives to resign, allowing the Liberals to form a government. Pearson stated that the condition of the economy required "a Government pledged to implement Liberal policies".[85] Government MPs laughed at Pearson, as did members of the press who were present. Pearson later recorded in his memoirs that he knew that his "first attack on the government had been a failure, indeed a fiasco".[85] Diefenbaker spoke for two hours and three minutes, and devastated his Liberal opposition. He mocked Pearson, contrasting the party leader's address at the Liberal leadership convention with his speech to the House:

On Thursday there was shrieking defiance, on the following Monday there is shrinking indecision ... The only reason that this motion is worded as it is[,] is that my honourable friends opposite quake when they think of what will happen if an election comes ... It is the resignation from responsibility of a great party.[86]

Diefenbaker read from an internal report provided to the St. Laurent government in early 1957, warning that a recession was coming, and stated:

Across the way, Mr. Speaker, sit the purveyors of gloom who would endeavour for political purposes, to panic the Canadian people ... They had a warning ... Did they tell us that? No. Mr. Speaker, why did they not reveal this? Why did they not act when the House was sitting in January, February, March, and April? They had the information ... You concealed the facts, that is what you did.[87]

According to the Minister of Finance, Donald Fleming, "Pearson looked at first merry, then serious, then uncomfortable, then disturbed, and finally sick."[86] Pearson recorded in his memoirs that the Prime Minister "tore me to shreds".[85] Prominent Liberal frontbencher Paul Martin called Diefenbaker's response "one of the greatest devastating speeches" and "Diefenbaker's great hour".[88] On February 1, Diefenbaker asked the Governor General, Vincent Massey, to dissolve Parliament, alleging that though St. Laurent had promised cooperation, Pearson had made it clear he would not follow his predecessor's lead. Massey agreed to the dissolution, and Diefenbaker set an election date of March 31, 1958.[89][90]

1958 election

[edit]The 1958 election campaign saw a huge outpouring of public support for the Progressive Conservatives. At the opening campaign rally in Winnipeg on February 12 voters filled the hall until the doors had to be closed for safety reasons. They were promptly broken down by the crowd outside.[91] At the rally, Diefenbaker called for "[a] new vision. A new hope. A new soul for Canada."[92] He pledged to open the Canadian North, to seek out its resources and make it a place for settlements.[91] The conclusion to his speech expounded on what became known as "The Vision",

This is the vision: One Canada. One Canada, where Canadians will have preserved to them the control of their own economic and political destiny. Sir John A. Macdonald saw a Canada from east to west: he opened the west. I see a new Canada—a Canada of the North. This is the vision![93]

Pierre Sévigny, who would be elected an MP in 1958, recalled the gathering, "When he had finished that speech, as he was walking to the door, I saw people kneel and kiss his coat. Not one, but many. People were in tears. People were delirious. And this happened many a time after."[94] When Sévigny introduced Diefenbaker to a Montreal rally with the words "Levez-vous, levez-vous, saluez votre chef!" (Rise, rise, salute your chief!) according to Postmaster General William Hamilton "thousands and thousands of people, jammed into that auditorium, just tore the roof off in a frenzy."[95] Michael Starr remembered, "That was the most fantastic election ... I went into little places. Smoky Lake, Alberta, where nobody ever saw a minister. Canora, Saskatchewan. Every meeting was jammed ... The halls would be filled with people and sitting there in the front would be the first Ukrainian immigrants with shawls and hands gnarled from work ... I would switch to Ukrainian and the tears would start to run down their faces ... I don't care who says what won the election; it was the emotional aspect that really caught on."[96]

Pearson and his Liberals faltered badly in the campaign. The Liberal Party leader tried to make an issue of the fact that Diefenbaker had called a winter election, generally disfavoured in Canada due to travel difficulties. Pearson's objection cut little ice with voters, and served only to remind the electorate that the Liberals, at their convention, had called for an election.[97] Pearson mocked Diefenbaker's northern plans as "igloo-to-igloo" communications, and was assailed by the Prime Minister for being condescending.[98] The Liberal leader spoke to small, quiet crowds, which quickly left the halls when he was done.[97] By election day, Pearson had no illusions that he might win the election, and hoped only to salvage 100 seats. The Liberals would be limited to less than half of that.[97]

On March 31, 1958, the Tories won what is still the largest majority (in terms of percentage of seats) in Canadian federal political history, winning 208 seats to the Liberals' 48, with the CCF winning 8 and Social Credit wiped out. The Progressive Conservatives won a majority of the votes and of the seats in every province except British Columbia (49.8%) and Newfoundland. Quebec's Union Nationale political machine had given the PC party little support, but with Quebec voters minded to support Diefenbaker, Union Nationale boss Maurice Duplessis threw the machinery of his party behind the Tories.[99]

Mandate (1958–1962)

[edit]

An economic downturn was beginning in Canada by 1958. Because of tax cuts instituted the previous year, the government's budget predicted a small deficit for 1957–58 and a large one, $648 million, for the following year. Minister of Finance Fleming and Bank of Canada Governor James Coyne proposed that the wartime Victory Bond issue, which constituted two-thirds of the national debt and which was due to be redeemed by 1967, be refinanced to a longer term. After considerable indecision on Diefenbaker's part, a nationwide campaign took place, and 90% of the bonds were converted. However, this transaction led to an increase in the money supply, which in future years would hamper the government's efforts to respond to unemployment.[100]

As a trial lawyer, and in opposition, Diefenbaker had long been concerned with civil liberties. On July 1, 1960, Dominion Day, he introduced the Canadian Bill of Rights in Parliament. The bill rapidly passed and was proclaimed on August 10, fulfilling a lifetime goal of Diefenbaker's, as he had begun drafting it as early as 1936.[101][8] The document purported to guarantee fundamental freedoms, with special attention to the rights of the accused. However, as a mere piece of federal legislation, it could be amended by any other law, and civil liberties were to a large extent a matter of provincial, rather than federal, jurisdiction. One lawyer remarked that the document provided rights for all Canadians, "so long as they don't live in any of the provinces".[102] Diefenbaker had appointed the first First Nations member of the Senate, James Gladstone, in January 1958,[103] and in 1960, his government extended voting rights to all native people.[13] In 1962, Diefenbaker's government eliminated race discrimination clauses in immigration laws.[104]

Diefenbaker pursued a "One Canada" policy, seeking equality of all Canadians. As part of that philosophy, he was unwilling to make special concessions to Quebec's francophones. Thomas Van Dusen, who served as Diefenbaker's executive assistant and wrote a book about him, characterized the leader's views on this issue:

There must be no compromise with Canada's existence as a nation. Opting out, two flags, two pension plans, associated states, Two Nations and all the other baggage of political dualism was ushering Quebec out of Confederation on the instalment plan. He could not accept any theory of two nations, however worded, because it would make of those neither French nor English second-class citizens.[105]

Diefenbaker's disinclination to make concessions to Quebec, along with the disintegration of the Union Nationale, the failure of the Tories to build an effective structure in Quebec, and Diefenbaker appointing few Quebeckers to his Cabinet (and none to senior positions), all led to an erosion of Progressive Conservative support in Quebec.[106] Diefenbaker did recommend the appointment of the first French-Canadian governor general, Georges Vanier.[13]

By mid-1961, differences in monetary policy led to open conflict with Bank of Canada Governor Coyne, who adhered to a tight money policy. Appointed by St. Laurent to a term expiring in December 1961, Coyne could only be dismissed before then by the passing of an Act of Parliament.[107] Coyne defended his position by giving public speeches, to the dismay of the government.[108] The Cabinet was also angered when it learned that Coyne and his board had passed amendments to the bank's pension scheme which greatly increased Coyne's pension, without publishing the amendments in the Canada Gazette as required by law. Negotiations between Minister of Finance Fleming and Coyne for the latter's resignation broke down, with the governor making the dispute public, and Diefenbaker sought to dismiss Coyne by legislation.[109] Diefenbaker was able to get legislation to dismiss Coyne through the House, but the Liberal-controlled Senate invited Coyne to testify before one of its committees. After giving the governor a platform against the government, the committee then chose to take no further action, adding its view that Coyne had done nothing wrong. Once he had the opportunity to testify (denied him in the Commons), Coyne resigned, keeping his increased pension, and the government was extensively criticized in the press.[110]

By the time Diefenbaker called an election for June 18, 1962, the party had been damaged by loss of support in Quebec and in urban areas[111] as voters grew disillusioned with Diefenbaker and the Tories. The PC campaign was hurt when the Bank of Canada was forced to devalue the Canadian dollar to 92+1⁄2 US cents; it had previously hovered in the range from 95 cents to par with the United States dollar. Privately printed satirical "Diefenbucks" swept the country.[112] On election day, the Progressive Conservatives lost 92 seats, but were still able to form a minority government. The New Democratic Party (the successor to the CCF) and Social Credit held the balance of power in the new Parliament.[111]

Foreign policy

[edit]Britain and the Commonwealth

[edit]

Diefenbaker attended a meeting of the Commonwealth Prime Ministers in London shortly after taking office in 1957. He generated headlines by proposing that 15% of Canadian spending on US imports instead be spent on imports from the United Kingdom.[113] Britain responded with an offer of a free trade agreement, which was rejected by the Canadians.[114] As the Harold Macmillan government in the UK sought to enter the Common Market, Diefenbaker feared that Canadian exports to the UK would be threatened. He also believed that the mother country should place the Commonwealth first, and sought to discourage Britain's entry. The British were annoyed at Canadian interference. Britain's initial attempt to enter the Common Market was vetoed by French President Charles de Gaulle.[115]

Through 1959, the Diefenbaker government had a policy of not criticizing South Africa and its apartheid government.[116] In this stance, Diefenbaker had the support of the Liberals but not that of CCF leader Hazen Argue.[117] In 1960, however, the South Africans sought to maintain membership in the Commonwealth even if South African white voters chose to make the country a republic in a referendum scheduled for later that year. South Africa asked that year's Commonwealth Prime Ministers' Conference to allow it to remain in the Commonwealth regardless of the result of the referendum. Diefenbaker privately expressed his distaste for apartheid to South African External Affairs Minister Eric Louw and urged him to give the black and coloured people of South Africa at least the minimal representation they had originally had. Louw, attending the conference as Prime Minister Hendrik Verwoerd recovered from an assassination attempt, refused.[118] The conference resolved that an advance decision would be interfering in South Africa's internal affairs.[119]

On October 5, 1960, South Africa's white voters decided to make the country a republic.[120] At the Prime Ministers' Conference in 1961, Verwoerd formally applied for South Africa to remain in the Commonwealth. The prime ministers were divided; Diefenbaker broke the deadlock by proposing that South Africa only be re-admitted if it joined other states in condemning apartheid in principle. Once it became clear that South Africa's membership would be rejected, Verwoerd withdrew his country's application to remain in the Commonwealth and left the group. According to Peter Newman, this was "Diefenbaker's most important contribution to international politics ... Diefenbaker flew home, a hero."[121]

Policy towards the United States

[edit]Ike and John: the Eisenhower years

[edit]

American officials were uncomfortable with Diefenbaker's initial election, believing they had heard undertones of anti-Americanism in the campaign. After years of the Liberals, one US State Department official noted, "We'll be dealing with an unknown quantity."[122] US officials viewed Diefenbaker's 1958 landslide with disappointment; they knew and liked Pearson from his years in diplomacy and felt the Liberal Party leader would be more likely to institute pro-American policies.[123] However, US President Dwight Eisenhower took pains to foster good relations with Diefenbaker. The two men found much in common, from Western farm backgrounds to a love of fishing, and Diefenbaker had an admiration for war leaders such as Eisenhower and Churchill.[124] Diefenbaker wrote in his memoirs, "I might add that President Eisenhower and I were from our first meeting on an 'Ike–John' basis, and that we were as close as the nearest telephone."[125] The Eisenhower–Diefenbaker relationship was sufficiently strong that the touchy Canadian Prime Minister was prepared to overlook slights. When Eisenhower addressed Parliament in October 1958, he downplayed trade concerns that Diefenbaker had publicly expressed. Diefenbaker said nothing and took Eisenhower fishing.[126]

Diefenbaker had approved plans to join the United States in what became known as NORAD, an integrated air defence system, in mid-1957.[127] Despite Liberal misgivings that Diefenbaker had committed Canada to the system before consulting either the Cabinet or Parliament, Pearson and his followers voted with the government to approve NORAD in June 1958.[128]

In 1959, the Diefenbaker government cancelled the development and manufacture of the Avro CF-105 Arrow. The Arrow was a supersonic jet interceptor built by Avro Canada in Malton, Ontario, to defend Canada in the event of a Soviet attack. The interceptor had been under development since 1953, and had suffered from many cost overruns and complications.[129] In 1955, the RCAF stated it would need only nine squadrons of Arrows, down from 20, as originally proposed.[129] According to C. D. Howe, the former minister responsible for postwar reconstruction, the St. Laurent government had serious misgivings about continuing the Arrow program, and planned to discuss its termination after the 1957 election.[130] In the run-up to the 1958 election, with three Tory-held seats at risk in the Malton area, the Diefenbaker government authorized further funding.[131] Even though the first test flights of the Arrow were successful, the US government was unwilling to commit to a purchase of aircraft from Canada.[132] In September 1958, Diefenbaker warned[133] that the Arrow would come under complete review in six months.[134] The company began seeking out other projects including a US-funded "saucer" program that became the VZ-9 Avrocar, and also mounted a public relations offensive urging that the Arrow go into full production.[135] On February 20, 1959, the Cabinet decided to cancel the Avro Arrow, following an earlier decision to permit the United States to build two Bomarc missile bases in Canada. The company immediately dismissed its 14,000 employees, blaming Diefenbaker for the firings, though it rehired 2,500 employees to fulfil existing obligations.[h]

Although the two leaders had a strong relationship, by 1960 US officials were becoming concerned by what they viewed as Canadian procrastination on vital issues, such as whether Canada should join the Organization of American States (OAS). Talks on these issues in June 1960 produced little in results.[126] Diefenbaker hoped that US Vice President Richard Nixon would win the 1960 US presidential election, but when Nixon's Democratic rival, Senator John F. Kennedy won the race, he sent Senator Kennedy a note of congratulations. Kennedy did not respond until Canadian officials asked what had become of Diefenbaker's note, two weeks later. Diefenbaker, for whom such correspondence was very meaningful, was annoyed at the President-elect's slowness to respond.[136] In January 1961, Diefenbaker visited Washington to sign the Columbia River Treaty. However, with only days remaining in the Eisenhower administration, little else could be accomplished.[137]

Bilateral antipathy: the Kennedy administration

[edit]

Kennedy and Diefenbaker started off well but matters soon worsened. When the two met in Washington on February 20, Diefenbaker was impressed by Kennedy, and invited him to visit Ottawa.[138] Kennedy, however, told his aides that he never wanted "to see the boring son of a bitch again".[139] The Ottawa visit began awkwardly. Kennedy accidentally left behind a briefing note suggesting he "push" Diefenbaker on several issues, including the decision to accept nuclear weapons on Canadian soil, which bitterly divided the Canadian Cabinet. Diefenbaker was also annoyed by Kennedy's speech to Parliament, in which he urged Canada to join the OAS (which Diefenbaker had already rejected),[140] and by the President spending most of his time talking to Leader of the Opposition Pearson at the formal dinner.[141][142] Both Kennedy and his wife Jackie were bored by Diefenbaker's Churchill anecdotes at lunch, stories that Jackie Kennedy later described as "painful".[143]

Diefenbaker was initially inclined to go along with Kennedy's request that nuclear weapons be stationed on Canadian soil as part of NORAD. However, when an August 3, 1961, letter from Kennedy which urged this was leaked to the media, Diefenbaker was angered and withdrew his support. The Prime Minister was also influenced by a massive demonstration against nuclear weapons, which took place on Parliament Hill. Diefenbaker was handed a petition containing 142,000 names.[144]

By 1962, the American government was becoming increasingly concerned at the lack of a commitment from Canada to take nuclear weapons. The interceptors and Bomarc missiles with which Canada was being supplied as a NORAD member were either of no use or of greatly diminished utility without nuclear devices.[145] Canadian and American military officers launched a quiet campaign to make this known to the press, and to advocate Canadian agreement to acquire the warheads.[146] Diefenbaker was also upset when Pearson was invited to the White House for a dinner for Nobel Prize winners in April, and met with the President privately for 40 minutes.[147] When the Prime Minister met with retiring American Ambassador Livingston Merchant, he angrily disclosed the paper Kennedy had left behind, and hinted that he might make use of it in the upcoming election campaign.[148] Merchant's report caused consternation in Washington, and the ambassador was sent back to see Diefenbaker again. This time, he found Diefenbaker calm, and the Prime Minister pledged not to use the memo, and to give Merchant advance word if he changed his mind.[149] Canada appointed a new ambassador to Washington, Charles Ritchie, who on arrival received a cool reception from Kennedy and found that the squabble was affecting progress on a number of issues.[150]

Kennedy was careful to avoid overt favouritism during the 1962 Canadian election campaign. Several times during the campaign, Diefenbaker stated that the Kennedy administration desired his defeat because he refused to "bow down to Washington".[151] After Diefenbaker was returned with a minority, Washington continued to press for acceptance of nuclear arms, but Diefenbaker, faced with a split between Defence Minister Douglas Harkness and External Affairs Minister Howard Green on the question, continued to stall, hoping that time and events would invite consensus.[152]

When the Cuban Missile Crisis erupted in October 1962, Kennedy chose not to consult with Diefenbaker before making decisions on what actions to take. The US president sent former Ambassador Merchant to Ottawa to inform the Prime Minister as to the content of the speech that Kennedy was to make on television. Diefenbaker was upset at both the lack of consultation and the fact that he was given less than two hours advance word.[153] He was angered again when the US government released a statement stating that it had Canada's full support.[154] In a statement to the Commons, Diefenbaker proposed sending representatives of neutral nations to Cuba to verify the American allegations, which Washington took to mean that he was questioning Kennedy's word.[155] When American forces went to a heightened alert, DEFCON 3, Diefenbaker was slow to order Canadian forces to match it. Harkness and the Chiefs of Staff had Canadian forces clandestinely go to that alert status anyway,[156] and Diefenbaker eventually authorized it.[157] The crisis ended without war, and polls found that Kennedy's actions were widely supported by Canadians. Diefenbaker was severely criticized in the media.[158]

Downfall

[edit]

On January 3, 1963, NATO Supreme Commander General Lauris Norstad visited Ottawa, in one of a series of visits to member nations prior to his retirement. At a news conference, Norstad stated that if Canada did not accept nuclear weapons, it would not be fulfilling its commitments to NATO. Newspapers across Canada criticized Diefenbaker, who was convinced the statement was part of a plot by Kennedy to bring down his government.[159] Although the Liberals had been previously indecisive on the question of nuclear weapons, on January 12, Pearson made a speech stating that the government should live up to its commitments.[160]

With the Cabinet still divided between adherents of Green and Harkness, Diefenbaker made a speech in the Commons on January 25 that Fleming (by then Minister of Justice) termed "a model of obfuscation".[161] Harkness was initially convinced that Diefenbaker was saying that he would support nuclear warheads in Canada. After talking to the press, he realized that his view of the speech was not universally shared, and he asked Diefenbaker for clarification. Diefenbaker, however, continued to try to avoid taking a firm position.[161] On January 30, the US State Department issued a press release suggesting that Diefenbaker had made misstatements in his Commons speech. For the first time ever, Canada recalled its ambassador to Washington as a diplomatic protest.[162] Though all parties condemned the State Department action, the three parties outside the government demanded that Diefenbaker take a stand on the nuclear weapon issue.[163]

The bitter divisions within the Cabinet continued, with Diefenbaker deliberating whether to call an election on the issue of American interference in Canadian politics. At least six Cabinet ministers favoured Diefenbaker's ouster. Finally, at a dramatic Cabinet meeting on Sunday, February 3, Harkness told Diefenbaker that the Prime Minister no longer had the confidence of the Canadian people, and resigned. Diefenbaker asked ministers supporting him to stand, and when only about half did, stated that he was going to see the Governor General to resign, and that Fleming would be the next prime minister. Green called his Cabinet colleagues a "nest of traitors", but eventually cooler heads prevailed, and the Prime Minister was urged to return and to fight the motion of non-confidence scheduled for the following day. Harkness, however, persisted in his resignation.[164] Negotiations with the Social Credit Party, which had enough votes to save the government, failed, and the government fell, 142–111.[165]

Two members of the government resigned the day after the government lost the vote.[166] As the campaign opened, the Tories trailed in the polls by 15 points. To Pearson and his Liberals, the only question was how large a majority they would win.[167] Peter Stursberg, who wrote two books about the Diefenbaker years, stated of that campaign:

For the old Diefenbaker was in full cry. All the agony of the disintegration of his government was gone, and he seemed to be a giant revived by his contact with the people. This was Diefenbaker's finest election. He was virtually alone on the hustings. Even such loyalists as Gordon Churchill had to stick close to their own bailiwicks, where they were fighting for their political lives.[168]

Though the White House maintained public neutrality, privately Kennedy made it clear he desired a Liberal victory.[169] Kennedy lent Lou Harris, his pollster to work for the Liberals again.[170] On election day, April 8, 1963, the Liberals claimed 129 seats to the Tories' 95, five seats short of an absolute majority. Diefenbaker held to power for several days, until six Quebec Social Credit MPs signed a statement that Pearson should form the government. These votes would be enough to give Pearson support of a majority of the House of Commons, and Diefenbaker resigned. The six MPs repudiated the statement within days. Nonetheless, Pearson formed a government with the support of the NDP.[171]

Later years (1963–1979)

[edit]Return to opposition

[edit]Diefenbaker continued to lead the Progressive Conservatives, again as Leader of the Opposition. In November 1963, upon hearing of Kennedy's assassination, the Tory leader addressed the Commons, stating, "A beacon of freedom has gone. Whatever the disagreement, to me he stood as the embodiment of freedom, not only in his own country, but throughout the world."[172] In the 1964 Great Canadian Flag Debate, Diefenbaker led the unsuccessful opposition to the Maple Leaf flag, which the Liberals pushed for after the rejection of Pearson's preferred design showing three maple leaves. Diefenbaker preferred the existing Canadian Red Ensign or another design showing symbols of the nation's heritage.[173] He dismissed the adopted design, with a single red maple leaf and two red bars, as "a flag that Peruvians might salute", a reference to Peru's red-white-red tricolour.[174] At the request of Quebec Tory Léon Balcer, who feared devastating PC losses in the province at the next election, Pearson imposed closure, and the bill passed with the majority singing "O Canada" as Diefenbaker led the dissenters in "God Save the Queen".[174]

In 1966, the Liberals began to make an issue of the Munsinger affair—two officials of the Diefenbaker government had slept with a woman suspected of being a Soviet spy. In what Diefenbaker saw as a partisan attack,[175] Pearson established a one-man Royal Commission, which, according to Diefenbaker biographer Smith, indulged in "three months of reckless political inquisition". By the time the commission issued its report, Diefenbaker and other former ministers had long since withdrawn their counsel from the proceedings. The report faulted Diefenbaker for not dismissing the ministers in question, but found no actual security breach.[176]

There were calls for Diefenbaker's retirement, especially from the Bay Street wing of the party as early as 1964. Diefenbaker initially beat back attempts to remove him without trouble.[177] When Pearson called an election in 1965 in the expectation of receiving a majority, Diefenbaker ran an aggressive campaign. The Liberals fell two seats short of a majority, and the Tories improved their position slightly at the expense of the smaller parties.[178] After the election, some Tories, led by party president Dalton Camp, began a quiet campaign to oust Diefenbaker.[13]

In the absence of a formal leadership review process, Camp was able to stage a de facto review by running for re-election as party president on the platform of holding a leadership convention within a year. His campaign at the Tories' 1966 convention occurred amidst allegations of vote rigging, violence, and seating arrangements designed to ensure that when Diefenbaker addressed the delegates, television viewers would see unmoved delegates in the first ten rows. Other Camp supporters tried to shout Diefenbaker down. Camp was successful in being re-elected thereby forcing a leadership convention for 1967.[179] Diefenbaker initially made no announcement as to whether he would stand, but angered by a resolution at the party's policy conference which spoke of "deux nations" or "two founding peoples" (as opposed to Diefenbaker's "One Canada"), decided to seek to retain his leadership.[13] Although Diefenbaker entered at the last minute to stand as a candidate for the leadership, he finished fifth on each of the first three ballots, and withdrew from the contest, which was won by Nova Scotia Premier Robert Stanfield.[180]

Diefenbaker addressed the delegates before Stanfield spoke:

My course has come to an end. I have fought your battles, and you have given me that loyalty that led us to victory more often than the party has ever had since the days of Sir John A. Macdonald. In my retiring, I have nothing to withdraw in my desire to see Canada, my country and your country, one nation.[181]

Final years and death

[edit]Diefenbaker was embittered by his loss of the party leadership. Pearson announced his retirement in December 1967, and Diefenbaker forged a wary relationship of mutual respect with Pearson's successor, Pierre Trudeau. Trudeau called a general election for June 1968; Stanfield asked Diefenbaker to join him at a rally in Saskatoon, which Diefenbaker refused, although the two appeared at hastily arranged photo opportunities. Trudeau obtained the majority against Stanfield that Pearson had never been able to obtain against Diefenbaker, as the PC party lost 25 seats, 20 of them in the West. The former prime minister, though stating, "The Conservative Party has suffered a calamitous disaster" in a CBC interview, could not conceal his delight at Stanfield's humiliation, and especially gloated at the defeat of Camp, who made an unsuccessful attempt to enter the Commons.[182] Diefenbaker was easily returned for Prince Albert.[182]

Although Stanfield worked to try to unify the party, Diefenbaker and his loyalists proved difficult to reconcile. The division in the party broke out in well-publicised dissensions, as when Diefenbaker called on Progressive Conservative MPs to break with Stanfield's position on the Official Languages bill, and nearly half the caucus voted against their leader's will or abstained.[183] In addition to his parliamentary activities, Diefenbaker travelled extensively and began work on his memoirs, which were published in three volumes between 1975 and 1977. Pearson died of cancer in 1972, and Diefenbaker was asked if he had kind words for his old rival. Diefenbaker shook his head and said only, "He shouldn't have won the Nobel Prize."[184]

By 1972, Diefenbaker had grown disillusioned with Trudeau, and campaigned wholeheartedly for the Tories in that year's election. Diefenbaker was re-elected comfortably in his home riding, and the Progressive Conservatives came within two seats of matching the Liberal total. Diefenbaker was relieved both that Trudeau had been humbled and that Stanfield had been denied power. Trudeau regained his majority two years later in an election that saw Diefenbaker, by then the only living former prime minister, have his personal majority grow to 11,000 votes.[185]

In the 1976 New Year Honours, Diefenbaker was created a Member of the Order of the Companions of Honour, an honour bestowed as the personal gift of the Sovereign.[186] After a long illness, Olive Diefenbaker died on December 22, a loss which plunged Diefenbaker into despair.[187]

Joe Clark succeeded Stanfield as party leader in 1976, but as Clark had supported the leadership review, Diefenbaker held a grudge against him.[188] Diefenbaker had supported Claude Wagner for leader, but when Clark won, stated that Clark would make "a remarkable leader of this party".[189] However, Diefenbaker repeatedly criticized his party leader, to such an extent that Stanfield publicly asked Diefenbaker "to stop sticking a knife into Mr. Clark"—a request Diefenbaker did not agree to.[190] According to columnist Charles Lynch, Diefenbaker regarded Clark as an upstart and a pipsqueak.[191]

In 1978, Diefenbaker announced that he would stand in one more election, and under the slogan "Diefenbaker—Now More Than Ever", weathered a campaign the following year during which he apparently suffered a mild stroke, although the media were told he was bedridden with influenza. In the May election Diefenbaker defeated NDP candidate Stan Hovdebo (who, after Diefenbaker's death, would win the seat in a by-election) by 4,000 votes. Clark had defeated Trudeau, though only gaining a minority government, and Diefenbaker returned to Ottawa to witness the swearing-in, still unreconciled to his old opponents among Clark's ministers. Two months later, Diefenbaker died of a heart attack in his study at age 83.[188]

Diefenbaker had extensively planned his funeral in consultation with government officials. He lay in state in the Hall of Honour in Parliament for two and a half days; 10,000 Canadians passed by his casket. The Maple Leaf Flag on the casket was partially obscured by the Red Ensign.[192][193] After the service, his body was taken by train on a slow journey to its final destination, Saskatoon; along the route, many Canadians lined the tracks to watch the funeral train pass. In Winnipeg, an estimated 10,000 people waited at midnight in a one-kilometre line to file past the casket which made the trip draped in a Canadian flag and Diefenbaker's beloved Red Ensign.[194] In Prince Albert, thousands of those he had represented filled the square in front of the railroad station to salute the only man from Saskatchewan ever to become prime minister. His coffin was accompanied by that of his wife Olive, disinterred from temporary burial in Ottawa. Prime Minister Clark delivered the eulogy, paying tribute to "an indomitable man, born to a minority group, raised in a minority region, leader of a minority party, who went on to change the very nature of his country, and change it forever".[192] John and Olive Diefenbaker rest outside the Diefenbaker Centre, built to house his papers, on the campus of the University of Saskatchewan.[192][195]

Legacy

[edit]

Some of Diefenbaker's policies did not survive the 16 years of Liberal government that followed his fall. This was especially true in the realm of foreign affairs: "By the time Diefenbaker left office," according to Canadian historian Robert Bothwell, "his conduct of foreign policy was reviled by an important and growing number of Canadians, while his relations with both the Americans and the British were disastrous."[196] By the end of 1963, the first of the Bomarc warheads entered Canada, where they remained until the last were finally phased out during John Turner's brief government in 1984.[197] Diefenbaker's decision to have Canada remain outside the OAS was not reversed by Pearson, and it was not until 1989, under the Tory government of Brian Mulroney, that Canada joined.[198]

Historian Conrad Black writes that Diefenbaker:

was not a successful prime minister; he was a jumble of attitudes but had little in the way of policy, was a disorganized administrator, and was inconsistent, indecisive, and not infrequently irrational. But he was very formidable; a deadly campaigner, an idiosyncratic but often galvanizing public speaker, a brilliant parliamentarian, and a man of many fine qualities. He was absolutely honest financially, a passionate supporter of the average and the underprivileged and disadvantaged person, a fierce opponent of any racial or religious or socioeconomic discrimination ...[199]

However, some defining features of modern Canada can be traced back to Diefenbaker. Diefenbaker's Bill of Rights remains in effect, and signaled the change in Canadian political culture that would eventually bring about the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which came into force after his death.[13] Canadian philosopher George Grant saw Diefenbaker's career as emblematic of the broader trajectory of Canadian national identity:

Diefenbaker's confusions and inconsistencies are to be seen as essential to the Canadian fate. His administration was not an aberration from which Canada will recover under the sensible rule of the established classes. It was a bewildered attempt to find policies that were adequate to its noble cause. The 1957 election was the Canadian people's last gasp of nationalism. Diefenbaker's government was the strident swansong of that hope.[200]

Diefenbaker has had several locations named in his honour, some before his 1979 death (particularly in his home province of Saskatchewan, including Lake Diefenbaker, the largest lake in Southern Saskatchewan, and the Diefenbaker Bridge in Prince Albert), others after (in 1993, Saskatoon renamed its airport the Saskatoon John G. Diefenbaker International Airport). The city of Prince Albert continues to maintain the house he resided in from 1947 to 1975 as a public museum known as Diefenbaker House; it was designated a National Historic Site in 2018.[201]

Diefenbaker reinvigorated a moribund party system in Canada. Clark and Mulroney, two men who, as students, worked on and were inspired by his 1957 triumph, became the only other Progressive Conservatives to lead the party to election triumphs.[i][186] Diefenbaker's biographer, Denis Smith, wrote of him, "In politics he had little more than two years of success in the midst of failure and frustration, but he retained a core of deeply committed loyalists to the end of his life and beyond. The federal Conservative Party that he had revived remained dominant in the prairie provinces for 25 years after he left the leadership."[13] The Harper government, believing that Tory prime ministers have been given short shrift in the naming of Canadian places and institutions, named the former Ottawa City Hall, now a federal office building, the John G. Diefenbaker Building. It also gave Diefenbaker's name to a human rights award and an icebreaking vessel. Harper often invoked Diefenbaker's northern vision in his speeches.[202]

Conservative Senator Marjory LeBreton worked in Diefenbaker's office during his second time as Opposition Leader, and has said of him, "He brought a lot of firsts to Canada, but a lot of it has been air-brushed from history by those who followed."[203] Historian Michael Bliss, who published a survey of the Canadian Prime Ministers, wrote of Diefenbaker:

From the distance of our times, Diefenbaker's role as a prairie populist who tried to revolutionize the Conservative Party begins to loom larger than his personal idiosyncrasies. The difficulties he faced in the form of significant historical dilemmas seem less easy to resolve than Liberals and hostile journalists opined at the time. If Diefenbaker defies rehabilitation, he can at least be appreciated. He stood for a fascinating and still relevant combination of individual and egalitarian values ... But his contemporaries were also right in seeing some kind of disorder near the centre of his personality and his prime-ministership. The problems of leadership, authority, power, ego, and a mad time in history overwhelmed the prairie politician with the odd name.[204]

Honorary degrees

[edit]Diefenbaker received several honorary degrees in recognition of his political career:

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ Known as the Conservatives before 1942.

- ^ Smith 1995, p. 3. Following his father's death, William Diefenbaker anglicized the spelling of "Diefenbacher", and changed its pronunciation so that the "baker" part of the name is pronounced like the English word "baker".

- ^ a b Smith 1995, p. 14. Note: Upon his brother's accession to the prime ministership, Elmer Diefenbaker sent him a letter recalling this childhood ambition.

- ^ Note: The exact phrasing of what Diefenbaker said to Laurier varies from source to source.

- ^ Smith 1995, p. 75. Thirty years later, the winning candidate, H. J. Fraser, challenged Diefenbaker for his parliamentary seat, and was defeated by a 5-to-1 margin. Newman 1963, p. 21.

- ^ Diefenbaker was a teetotaler. (Diefenbaker 1976, pp. 191)

- ^ Meisel 1962, p. 291. The 112th seat was not obtained until July 15, as the election in one riding was not held until then due to the death of the original Liberal candidate. Meisel 1962, p. 235. Additionally, the Liberal victory in Yukon was vacated by the Yukon Territorial Court and a Tory won the new election in December 1957. Meisel 1962, p. 239.

- ^ Smith 1995, pp. 317–320. Over 50,000 other jobs were affected in the supply chain. Peden 1987, p. 157.

- ^ Kim Campbell also became a PC Prime Minister, but she never won an election to gain that role.

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Smith 1995, p. 1.

- ^ Diefenbaker 1975, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Smith 1995, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Newman 1963, p. 15.

- ^ a b Newman 1963, p. 16.

- ^ Charlton, Jonathan (July 25, 2017). "Meeting in Saskatoon between Diefenbaker and Laurier never happened, author says". The StarPhoenix. Archived from the original on November 9, 2020. Retrieved January 27, 2019.

- ^ "Man calls for removal of Saskatoon Diefenbaker statue because he says it is based on lies". CBC News. July 27, 2017. Archived from the original on October 21, 2020. Retrieved July 27, 2017.

- ^ a b "John Diefenbaker and the Canadian Bill of Rights". CBC. Archived from the original on November 5, 2021. Retrieved November 5, 2021.

- ^ "The Canadian Bill of Rights". Diefenbaker Canada Centre. Archived from the original on November 5, 2021. Retrieved November 5, 2021.

- ^ Smith 1995, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Smith 1995, pp. 19–20.

- ^ "Soldiers of the First World War – Item: DIEFENBAKER, JOHN GEORGE BANNERMAN". Library and Archives Canada. August 23, 2013. Archived from the original on October 27, 2020. Retrieved September 15, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Smith 2016.

- ^ Smith 1995, pp. 20–30.

- ^ a b Smith 1995, pp. 31–33.

- ^ Diefenbaker 1975, p. 79.

- ^ Smith 1995, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Newman 1963, p. 18.

- ^ Smith 1995, p. 38.

- ^ Smith 1995, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Smith 1995, p. 41.

- ^ Diefenbaker 1975, p. 64.

- ^ Smith 1995, pp. 41–42.

- ^ Smith 1995, p. 43.

- ^ Newman 1963, pp. 19–20.