Psychro Cave

| Psychro Cave | |

|---|---|

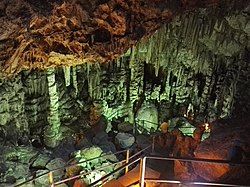

Floodlit stalagmites and stalactites in the cave’s interior | |

| Location | Crete, Greece |

| Coordinates | 35°09′46″N 25°26′42″E / 35.1629°N 25.4451°E |

Psychro Cave (Greek: Σπήλαιο Ψυχρού) is an ancient Minoan sacred cave in Lasithi plateau in the Lasithi district of eastern Crete. Psychro is associated with the Diktaean Cave (Greek: Δικταῖον Ἄντρον; Diktaion Antron), one of the putative sites of the birth of Zeus. Other legends place Zeus' birthplace as Idaean Cave (Ἰδαῖον Ἄντρον) on Mount Ida. According to Hesiod, Theogony (477-484), Rhea gave birth to Zeus in Lyctus and hid him in a cave of Mount Aegaeon. Since the late nineteenth century the cave above the modern village of Psychro has been identified with Diktaean Cave, although there are other candidates, especially a cave above Palaikastro on Mount Petsofas.[1]

Geography

[edit]The village of Psychro (35°09′54″N 25°27′04″E / 35.165°N 25.451°E) is 1,025 metres above sea level.[citation needed] The cave is located in the prefecture of Lasithi. In Minoan times, the town of Malia was the closest metropolitan center.

Myth

[edit]Dictaean Cave is famous in Greek mythology as the place where Amalthea, nurtured the infant Zeus with her goat's milk. The archaeology attests to the site's long use as a place of cult worship. The nurse of Zeus, who was charged by Rhea to raise the infant Zeus in secret here, to protect him from his father Cronus (Krónos) is also called the nymph Adrasteia in some contexts.[2] It is one of a number of caves believed to have been the birthplace or hiding place of Zeus.[3] The mountains, of which the cave are part, are known in Crete as Dikte.

Archaeology

[edit]The cave was first excavated in 1886 by Joseph Hatzidakis, President of the Syllogos at Candia, and F. Halbherr.[4] In 1896, Sir Arthur Evans investigated the site.[5]

In 1898 Pierre Demargne conducted brief investigations,[6] followed by David George Hogarth of the British School at Athens in 1900 who carried out more extensive operations. Hogarth's reports published in 1900[7] give a picture of the destruction wrought by primitive archaeological methods: immense fallen blocks from the upper cave roof were blasted before removal; the rich black earth had been previously ransacked. The stuccoed altar in the upper cave was discovered in 1900, surrounded by strata of ashes, pottery and "other refuse", among which were votive objects in bronze, terracotta, iron and bone, with fragments of some thirty libation tables and countless conical ceramic cups for food offerings. Bones among the ash layer attest to sacrifice of bulls, sheep and goats, deer and a boar.[8]

The undisturbed lowest strata of the upper cave represented the transition between Late Minoan Kamares ware to earliest Mycenaean levels; finds represented the Geometric Style of the ninth century BCE, but few later than that. More recent excavation has revealed the use of the cave reached back to Early Minoan times, and votive objects attest to the cave's being the most frequented shrine by Middle Minoan times (MM IIIA).[9]

The lower grotto falls steeply with traces of a rock-cut stair to a pool, out of which stalactites rise. "Much earth had been thrown down by diggers of the Upper Grotto," Hogarth reported, "and this was found full of small bronze objects." In the vertical chinks of the lowest stalactites, Hogarth's team found "toy double-axes, knife-blades, needles, and other objects in bronze, placed there by dedicators, as in niches. The mud at the edge of the subterranean pool was also rich in similar things and in statuettes of two types, male and female and engraved gems."

In 1961, the art historian and archaeologist John Boardman published the finds uncovered by these and other excavations.[citation needed]

While clay human figurines are normally found in peak sanctuaries, Psychro and the sanctuary on Mount Ida stand out as the only sacred caves that have yielded human figurines. Psychro is also a unique sacred cave for a bronze leg, also known as a votive body part, which is the only votive body part to be found in a sacred cave. More common sacred cave finds at Psychro include stone and ceramic lamps.

Psychro yielded an uncommon number of semi-precious stones, including carnelian, steatite, amethyst, jasper and hematite.

Psychro's artefacts are now on display at the Heraklion Museum, the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, the Louvre and the British Museum.[10]

Idaean Cave

[edit]

Idaean Cave (Greek: Ιδαίο άντρο) is a system of caves located on the slopes of Mount Ida on Crete (35°12′30″N 24°49′44″E / 35.2082°N 24.8290°E). The deep cave has a single entrance and features stalagmites and stalactites.

In antiquity it was a place of worship because it was believed to be the cave where the titan Rhea hid the infant Zeus, to protect him from his father Cronus, who intended to swallow him like others of his progeny. It is one of a number of caves believed to have been the birthplace or hiding place of Zeus.[3] According to a variant of this legend, the Kouretes, a band of mythical warriors, undertook to dance their wild, noisy war dances in front of the cave, so that the clamour would keep Cronus from hearing the infant's crying.

Excavations have revealed a large number of votive cult offerings on the site.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ MacGillivray, Alexander, and Hugh Sackett. “The Palaikastro Kouros: the Cretan God as a Young Man”, p. 167, British School at Athens Studies, vol. 6, 2000, pp. 165–169. JSTOR. Accessed 22 Feb. 2021

- ^ Bibliotheke, 1.1.6.

- ^ a b William Smith, ed. (c. 1873). A Dictionary of Greek and Roman biography and mythology. John Murray.

- ^ F. Halbherr and P. Orsi, "Scoperte nell' Antro di Psychro", Museo dell' Antichità Classico 2 1888 pp. 905-10.

- ^ Evans, "Further discoveries of Cretan and Aegean scripts," JHS 17 (1897), pp 305-57.

- ^ P. Demargne, "Antiquités de Praesos et de l'Antre Dictéen" Bulletin de Correspondence Héllenique 26 (1902), pp. 571-583.

- ^ D. G. Hogarth, "The Cave of Psychro in Crete" The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 30 (1900), pp. 90-91; D. G. Hogarth, "The Dictaean cave" The Annual of the British School at Athens 6 (1899/1900), pp. 94-116.

- ^ W. Boyd-Dawkins, "Remains of Animals Found in the Dictaean Cave in 1901," Man 32 (1902) Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, pp. 162-65.

- ^ L. Vance Watrous and H. Blitzer, "Lasithi: A History of Settlement on a Highland Plain in Crete" Hesperia Supplements 18 (1982), pp. i-xiv,1-122.

- ^ British Museum Collection

References

[edit]- Jones, Donald W. (1999). Peak Sanctuaries and Sacred Caves in Minoan Crete ISBN 91-7081-153-9

- Rutkowski, B., and Krzysztof Nowicki (1996). The Psychro Cave and Other Sacred Grottoes in Crete (Warsaw: Polish Academy of Science)

- Watrous, L. Vance (1996). The Cave Sanctuary of Zeus at Psychro: A Study of Extra-Urban Sanctuaries in Minoan and Early Iron Age Crete (Liège/Austin: Université de Liège / University of Texas at Austin)