George Michael

George Michael | |

|---|---|

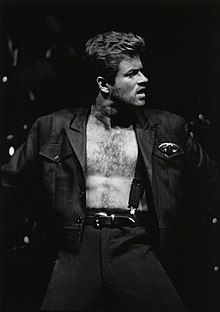

Michael performing in Houston, 1988 | |

| Born | Georgios Kyriacos Panayiotou 25 June 1963 East Finchley, Middlesex, England |

| Died | 25 December 2016 (aged 53) Goring-on-Thames, England |

| Resting place | Highgate Cemetery West, London |

| Other names | Yog |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1981–2016 |

| Partners |

|

| Musical career | |

| Genres | |

| Instruments |

|

| Labels | |

| Formerly of | |

| Website | georgemichael |

| Signature | |

| |

George Michael (born Georgios Kyriacos Panayiotou; 25 June 1963 – 25 December 2016) was an English singer-songwriter and record producer. Regarded as a pop culture icon,[2] he is one of the best-selling musicians of all time, with his sales estimated at between 100 million to 125 million records worldwide.[3][4] Michael was known as a creative force in songwriting,[5] vocal performance,[6] and visual presentation.[7][8] He achieved 10 number-one songs on the US Billboard Hot 100 and 13 number-one songs on the UK singles chart. Michael won numerous music awards, including two Grammy Awards, three Brit Awards, twelve Billboard Music Awards, and four MTV Video Music Awards. He was listed among Billboard's the "Greatest Hot 100 Artists of All Time" and Rolling Stone's the "200 Greatest Singers of All Time".[9] The Radio Academy named him the most played artist on British radio during the period 1984–2004.[10] Michael was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2023.[11]

Born in East Finchley, Middlesex, Michael rose to fame after forming the pop duo Wham! with Andrew Ridgeley in 1981. Their first two albums, Fantastic (1983) and Make It Big (1984), reached number one on the US Billboard 200 and UK Albums Chart. They had commercial success with singles "Wham Rap! (Enjoy What You Do)", "Young Guns (Go for It)", "Bad Boys", "Club Tropicana", "Wake Me Up Before You Go-Go", "Last Christmas", "Everything She Wants", "Freedom", and "I'm Your Man". Their 1985 tour in China was the first by a Western popular music act, and generated worldwide media coverage.[12][13] Michael took part in Band Aid's UK number-one single "Do They Know It's Christmas?" in 1984 and performed at the following year's Live Aid concert.

Michael's first solo single, "Careless Whisper" (1984), reached number one in over 20 countries, including the UK and US.[14][15] The second solo single, "A Different Corner", also reached number one in 1986. After Wham! disbanded that year, Michael released the number-one duet with Aretha Franklin, "I Knew You Were Waiting (For Me)". His debut solo album, Faith (1987), stayed at number one on the Billboard 200 for 12 weeks and topped the UK Albums Chart. It is one of the best-selling albums of all time, having sold over 25 million copies worldwide. The singles "Faith", "Father Figure", "One More Try", and "Monkey" reached number one on the Billboard Hot 100. Michael became the best-selling music artist of 1988, and Faith was awarded Album of the Year at the 1989 Grammy Awards. Michael's second solo album, Listen Without Prejudice Vol. 1 (1990), was also a number one in the UK and yielded the Billboard Hot 100 number one "Praying for Time" and the worldwide hit "Freedom! '90".[16] Michael went on to release a series of multimillion-selling albums, including Older (1996), Ladies & Gentlemen: The Best of George Michael (1998), Songs from the Last Century (1999), Patience (2004), and Twenty Five (2006). The albums earned him multiple hits such as "Jesus to a Child", "Fastlove", "Outside", "Amazing", and "An Easier Affair".

Michael came out as gay in 1998, and was an active LGBT rights campaigner and HIV/AIDS charity fundraiser. His personal life, drug use, and legal troubles made headlines following an arrest for public lewdness in 1998 and multiple drug-related offences. The 2005 documentary A Different Story covered his career and personal life. His 25 Live tour spanned three tours from 2006 to 2008. In 2011 Michael fell into a coma during a bout with pneumonia, but recovered. He performed his final concert at London's Earls Court in 2012. Michael died of heart disease on Christmas Day in 2016, at his home in Goring-on-Thames, Oxfordshire.

Early life

George Michael was born Georgios Kyriacos Panayiotou (Greek: Γεώργιος Κυριάκος Παναγιώτου) on 25 June 1963, in East Finchley. He was the only son and the youngest child of three.[17][18] His father, Kyriacos "Jack" Panayiotou,[19] was a Greek Cypriot restaurateur who emigrated from Patriki, Cyprus, to England in the 1950s.[20] His mother, Lesley Angold (born Harrison, died 1997),[21][22][23] was an English dancer.[24] In June 2008, Michael told the Los Angeles Times that his maternal grandmother was Jewish, but she had married a non-Jewish man and raised their children with no knowledge of their Jewish background due to her fear during World War II.[25]

Michael spent most of his childhood in Kingsbury, London, in the home his parents bought soon after his birth; he attended Roe Green Junior School and Kingsbury High School.[26][27] Michael had two sisters: Yioda (born 1958) and Melanie (1960–2019).[21][28] On BBC's Desert Island Discs, Michael said that his interest in music followed an injury to his head around the age of eight.[29]

Early music

While Michael was in his early teens, the family moved to Radlett.[30][31] There, Michael began attending Bushey Meads School in Bushey,[32] where he, as "Yog", met, sat down next to, and befriended, his future Wham! partner Andrew Ridgeley. The two had the same career ambition of being musicians.[19] Michael busked on the London Underground, performing songs such as "'39" by Queen.[33] His involvement in the music business began with his working as a DJ, playing at the Bel Air Restaurant in Northwood, London,[34][35][36][37] clubs, and local schools around Bushey, Stanmore, and Watford. This was followed by the formation of a short-lived ska band called the Executive, with Ridgeley, Ridgeley's brother Paul, Andrew Leaver, Jamie Gould, and David Mortimer (later known as David Austin).[38]

Wham!

Michael formed the duo Wham! with Andrew Ridgeley in 1981. On the cusp of fame, he decided to legally change his name to the more accessible George Michael.[5] The band's first album Fantastic reached No. 1 in the UK in 1983 and produced a series of top 10 singles including "Young Guns", "Wham Rap!", and "Club Tropicana". Their second album, Make It Big, reached No. 1 on the charts in the US. Singles from that album included "Wake Me Up Before You Go-Go" (No. 1 in the UK and US), "Freedom", "Everything She Wants", and "Careless Whisper" which reached No. 1 in nearly 25 countries, including the UK and US, and was Michael's first solo effort as a single.[14][15] In December 1984, the single "Last Christmas" was released.[39] In 1985 Michael received the first of his three Ivor Novello Awards for Songwriter of the Year from the British Academy of Songwriters, Composers and Authors.[40]

Michael performed on the original 1984 Band Aid recording of "Do They Know It's Christmas?"—he appears third on the song after Paul Young and Boy George sing their lines.[41] The song became the UK Christmas number one and Michael also donated the profits from "Last Christmas" and "Everything She Wants" to charity.[42] Michael sang "Don't Let the Sun Go Down on Me" with Elton John at Live Aid at Wembley Stadium in London on 13 July 1985.[43] He also contributed background vocals to David Cassidy's 1985 hit "The Last Kiss", as well as Elton John's 1985 successes "Nikita" and "Wrap Her Up". Michael cited Cassidy as a major career influence and interviewed Cassidy for David Litchfield's Ritz Newspaper.[44]

Wham!'s tour of China in April 1985, the first visit to China by a Western popular music act, generated worldwide media coverage, much of it centred on Michael.[12][13] The headline in the Chicago Tribune read: "East meets Wham!, and another great wall comes down".[13] Before Wham!'s appearance in China, many kinds of music in the country were forbidden.[12] The band's manager, Simon Napier-Bell, had spent 18 months trying to convince Chinese officials to let the duo play.[12] The audience included members of the Chinese government. Chinese television presenter Kan Lijun, who was the on-stage host, spoke of Wham!'s historic performance:

"No-one had ever seen anything like that before. All the young people were amazed and everybody was tapping their feet. Of course the police weren't happy and they were scared there would be riots."[12]

Wham! performed their hits with scantily clad dancers and strobing disco lights. According to Napier-Bell, Michael tried to get the crowd to clap along to "Club Tropicana", but "they hadn't a clue – they thought he wanted applause and politely gave it", before adding that some Chinese did eventually "get the hang of clapping on the beat."[45] A UK embassy official in China stated "there was some lively dancing but this was almost entirely confined to younger western members of the audience."[45] The tour was documented by film director Lindsay Anderson and producer Martin Lewis in their film Wham! in China: Foreign Skies.[46]

With the success of Michael's solo singles, "Careless Whisper" (1984) and "A Different Corner" (1986), rumours of an impending break up of Wham! intensified. The duo officially separated in 1986, after releasing a farewell single, "The Edge of Heaven" and a farewell compilation, The Final (their third album Music from the Edge of Heaven was released in North America and Japan), plus a sell-out concert at Wembley Stadium that included the world premiere of the China film.[47] The Wham! partnership ended officially with the commercially successful single "The Edge of Heaven", which reached No. 1 on the UK chart in June 1986.[48]

Solo career

1987–1989

During early 1987, at the beginning of his solo career, Michael released "I Knew You Were Waiting (For Me)", a duet with Aretha Franklin. "I Knew You Were Waiting (For Me)" was a one-off project that helped Michael achieve an ambition by singing with one of his favourite artists. It scored number one on both the UK Singles Chart and the US Billboard Hot 100 upon its release.[49][50] For Michael, it became his third consecutive solo number one in the UK from three releases, after 1984's "Careless Whisper" (though the single was actually from the Wham! album Make It Big) and 1986's "A Different Corner". The single was also the first Michael had recorded as a solo artist which he had not written himself. The co-writer, Simon Climie, was unknown at the time; he later had success as a performer with the band Climie Fisher in 1988. Michael and Franklin won a Grammy Award in 1988 for Best R&B Performance – Duo or Group with Vocal for the song.[51]

In late 1987, Michael released his debut solo album, Faith. The first single released from the album was "I Want Your Sex", in mid-1987. The song was banned by many radio stations in the UK and US, due to its sexually suggestive lyrics.[52] MTV broadcast the video, featuring celebrity make-up artist Kathy Jeung in a basque and suspenders, only during the late night hours.[52] Michael argued that the act was beautiful if the sex was monogamous, and he recorded a brief prologue for the video in which he said: "This song is not about casual sex."[53] One of the racier scenes involved Michael writing the words "explore monogamy" on his partner's back in lipstick.[54] Some radio stations played a toned-down version of the song, "I Want Your Love", with the word "love" replacing "sex".[55]

When "I Want Your Sex" reached the US charts, American Top 40 host Casey Kasem refused to say the song's title, referring to it only as "the new single by George Michael."[55] In the US, the song was also sometimes listed as "I Want Your Sex (from Beverly Hills Cop II)", since the song was featured on the soundtrack of the movie.[56] Despite censorship and radio play problems, "I Want Your Sex" reached No. 2 on the US Billboard Hot 100 and No. 3 in the UK.[14][57] The second single, "Faith", was released in October 1987, a few weeks before the album. "Faith" became one of his most popular songs. The song was No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100 for four consecutive weeks, becoming the best-selling single of 1988 in the US.[15] It also reached No. 1 in Australia, and No. 2 on the UK Singles Chart.[14] The video provided some definitive images of the 1980s music industry in the process—Michael in shades, leather jacket, cowboy boots, and Levi's jeans, playing a guitar near a classic-design jukebox.[58]

On 30 October, Faith was released in the UK and in several markets worldwide.[56] Faith topped the UK Albums Chart, and in the US, the album had 51 non-consecutive weeks in the top 10 of Billboard 200, including 12 weeks at No. 1. Faith had many successes, with four singles ("Faith", "Father Figure", "One More Try", and "Monkey") reaching No. 1 in the US.[59] Faith was certified Diamond by the RIAA for sales of 10 million copies in the US.[60] To date, global sales of Faith are more than 25 million units.[61] The album was highly acclaimed by music critics, with AllMusic journalist Steve Huey describing it as a "superbly crafted mainstream pop/rock masterpiece" and "one of the finest pop albums of the '80s".[62] In a review by Rolling Stone magazine, journalist Mark Coleman commended most of the songs on the album, which he said "displays Michael's intuitive understanding of pop music and his increasingly intelligent use of his power to communicate to an ever-growing audience."[63]

In 1988, Michael embarked on a world tour.[64] In Los Angeles, Michael was joined on stage by Aretha Franklin for "I Knew You Were Waiting (For Me)". It was the second highest grossing event of 1988, earning $17.7 million.[65] At the 1988 Brit Awards held at the Royal Albert Hall on 8 February, Michael received the first of his two awards for Best British Male Solo Artist. Later that month, Faith won the Grammy Award for Album of the Year at the 31st Grammy Awards.[66] At the 1989 MTV Video Music Awards on 6 September in Los Angeles, Michael received the Video Vanguard Award.[67] According to Michael in his film, A Different Story, success did not make him happy and he started to think there was something wrong in being an idol for millions of teenage girls. The whole Faith process (promotion, videos, tour, awards) left him exhausted, lonely and frustrated, and far from his friends and family.[68] In 1990, he told his record company Sony that, for his second album, he did not want to do promotions like the one for Faith.[69]

1990s

Listen Without Prejudice Vol. 1 was released in September 1990. The title is an indication of his desire to be taken more seriously as a songwriter.[70] The album was released in Europe on 3 September 1990, and one week later in the US. It reached No. 1 in the UK Albums Chart[14] and peaked at No. 2 on the US Billboard 200.[15] It spent a total of 88 weeks on the UK Albums Chart and was certified four-times Platinum by the BPI.[71] The album produced five UK singles, all of which were released within an eight-month period: "Praying for Time", "Waiting for That Day", "Freedom! '90", "Heal the Pain", and "Cowboys and Angels" (the latter being his only single not to chart in the UK top 40).[14] Michael refused to do any promotion for the album.[69] At the 1991 Brit Awards, Listen Without Prejudice Vol. 1 won the award for Best British Album.[72]

The album's first single, "Praying for Time", with lyrics concerning social ills and injustice, was released in August 1990. James Hunter of Rolling Stone magazine described the song as "a distraught look at the world's astounding woundedness. Michael offers the healing passage of time as the only balm for physical and emotional hunger, poverty, hypocrisy, and hatred."[73] The song was an instant success, reaching No. 1 on the US Billboard Hot 100 and No. 6 in the UK.[15] A video was released shortly thereafter, consisting of the lyrics on a dark background. Michael did not appear in this video or any subsequent videos for the album.[70] The second single from Listen Without Prejudice Vol. 1, "Waiting for That Day", was an acoustic-heavy single, released as an immediate follow-up to "Praying for Time".

"Freedom! '90" was the second of only two singles from Listen Without Prejudice to be supported by a music video (the other being the Michael-less "Praying for Time").[74] The song alludes to his struggles with his artistic identity, and prophesied his efforts shortly thereafter to end his recording contract with Sony Music. As if to prove the song's sentiment, Michael refused to appear in the video (directed by David Fincher), and instead recruited supermodels Naomi Campbell, Linda Evangelista, Christy Turlington, Tatjana Patitz, and Cindy Crawford to appear in and lip sync in his stead.[74] It also featured lyrics critical of his sex symbol status.[75] It reached No. 8 on the Billboard Hot 100 in the US,[15] and No. 28 on the UK Singles Chart.[14] "Mother's Pride" gained significant radio play in the US during the first Persian Gulf War during 1991, often with radio stations mixing in callers' tributes to soldiers with the music.[76]

Later in 1991, Michael embarked on the Cover to Cover tour in Japan, England, the US, and Brazil, where he performed at Rock in Rio.[77] The tour was not a proper promotion for Listen Without Prejudice Vol. 1. Rather, it featured Michael singing his favourite cover songs.[77] Among his favourites was "Don't Let the Sun Go Down on Me", a 1974 song by Elton John; Michael and John had performed the song together at the Live Aid concert in 1985, and again for Michael's concert at London's Wembley Arena on 25 March 1991, where the duet was recorded. "Don't Let the Sun Go Down on Me" was released as a single at the end of 1991 and reached No. 1 in both the UK and US.[78] In 1991, Michael released an autobiography through Penguin Books titled Bare, co-written with Tony Parsons.[79]

An expected follow-up album, Listen Without Prejudice Vol. 2, was scrapped due to Michael's lawsuit with Sony.[80] Instead, Michael donated three songs to the charity project Red Hot + Dance, for the Red Hot Organization which raised money for AIDS awareness; a fourth track, "Crazyman Dance", was the B-side of 1992's "Too Funky". Michael donated the royalties from "Too Funky" to the same cause.[81] "Too Funky" reached No. 4 on the UK Singles Chart[14] and No. 10 on the US Billboard Hot 100.[15]

"George Michael was the best. There's a certain note in his voice when he did 'Somebody to Love' that was pure Freddie."

Michael performed with Queen at The Freddie Mercury Tribute Concert on 20 April 1992 at Wembley Stadium.[83] The concert was a tribute to the life of the late Queen frontman, Freddie Mercury, with the proceeds going to AIDS research.[84] Michael performed "'39", "These Are the Days of Our Lives" with Lisa Stansfield and "Somebody to Love". Michael's performance of "Somebody to Love" was hailed as "one of the best performances of the tribute concert".[85][86] Michael later reflected, "It was probably the proudest moment for me of my career, because it was me living out a childhood fantasy, I suppose, to sing one of Freddie's songs in front of 80,000 people."[87]

The Five Live EP[88] featured five live recordings (six in several countries) performed by Michael, Queen, and Lisa Stansfield. "Somebody to Love" and "These Are the Days of Our Lives" were recorded at the Freddie Mercury Tribute Concert. "Killer", "Papa Was a Rollin' Stone", and "Calling You" were recorded during his Cover to Cover tour in 1991.[85][86] All proceeds from the sale of the EP benefited the Mercury Phoenix Trust.[89] Sales of the EP were strong through Europe, where it debuted at No. 1 in the UK and several European countries.[14] Chart success in the US was less spectacular, where it reached No. 40 on the Billboard 200 ("Somebody to Love" reached No. 30 on the US Billboard Hot 100).[15] The performance would later feature on Queen's compilation album Greatest Hits III.[90]

During November 1994, after a long period of seclusion, Michael appeared at the first MTV Europe Music Awards show, where he gave a performance of a new song, "Jesus to a Child".[91] The song was a melancholy tribute to his lover, Anselmo Feleppa, who had died in March 1993. The song entered the UK Singles Chart at No. 1 and No. 7 on Billboard upon release in 1996.[14][15] It was Michael's longest UK Top 40 single, at almost seven minutes long. The exact identity of the song's subject—and the nature of Michael's relationship with Feleppa—was shrouded in innuendo and speculation, as Michael had not confirmed he was homosexual and did not do so until 1998. The video for "Jesus to a Child" was a picture of images recalling loss, pain and suffering. Michael consistently dedicated the song to Feleppa before performing it live.[92]

Michael released "Fastlove", an energetic tune about wanting gratification and fulfilment without commitment, in 1996. The single version was nearly five minutes long. "Fastlove" was supported by a futuristic virtual reality-related video. The single reached No. 1 on the UK Singles Chart, spending three weeks at the top spot.[14] In the US, "Fastlove" peaked at No. 8.[15] Following "Fastlove", Michael released Older, his third studio album.[93] In the UK, the album was particularly notable for producing a record six top three hit singles in a two-year span.[94]

In 1996, Michael was voted Best British Male at the MTV Europe Music Awards and the Brit Awards;[95][96] and at the British Academy's Ivor Novello Awards, he was awarded the title of Songwriter of the Year for the third time.[97] Michael performed a concert at Three Mills Studios, London, for MTV Unplugged.[98] It was his first long performance in years, and in the audience was Michael's mother, who died of cancer the following year.[99]

Ladies & Gentlemen: The Best of George Michael (1998) was Michael's first solo greatest hits collection. The collection of 28 songs (29 songs are included on the European and Australian release) are separated into two-halves, with each containing a particular theme and mood. The first CD, titled "For the Heart", predominantly contains ballads; the second CD, "For the Feet", consists mainly of dance tunes. It was released through Sony Music Entertainment as a condition of severing contractual ties with the label.[100] Ladies & Gentlemen was a success, peaking at No. 1 on the UK Albums Chart for eight weeks.[14] It spent over 200 weeks in the UK chart, and is the 45th best-selling album ever in the UK.[101] It is certified seven-times platinum in the UK and multi-platinum in the US, and is Michael's most commercially successful album in his homeland, having sold more than 2.8 million copies.[71] As of 2013, the album had reached worldwide sales of approximately 15 million copies.[102] The first single of the album, "Outside", was a humorous song making a reference to his arrest for soliciting a policeman in a public toilet. "As", his duet with Mary J. Blige, was released as the second single in many territories around the world. Both singles reached the top 5 in the UK Singles Chart.[14]

Released in 1999, Songs from the Last Century is a studio album of cover tracks. The album achieved the lowest peak of his solo efforts, peaking at No. 157 on the American Billboard 200 albums chart[15] and at No. 2 in the UK Albums Chart.[14]

2000s

In 2000, Michael worked on the hit single "If I Told You That" with Whitney Houston.[103] Michael co-produced on the single along with Rodney Jerkins.[104] Michael's first single from his fifth studio album, "Freeek!", reached the Top 10 in the UK.[105] His next single was "Shoot the Dog" which was released in July 2002 during the lead-up to the 2003 invasion of Iraq. The video for the song showed Tony Blair as George Bush's poodle.[106] The single's cover featured the Daily Mirror's "Howdy Poodle" front page from earlier in the year. Responding to criticism, Michael said, "I am British, I live here, I pay my taxes, and I'm very, very worried that we are now the second most dangerous country in the world thanks to our special relationship with America."[107] It reached No. 1 in Denmark and made the top 5 in most European charts.[108] It peaked at No. 12 on the UK Singles Chart.[14]

In February 2003, Michael recorded another song in protest against the looming Iraq war, Don McLean's "The Grave". The original was written by McLean in 1971 and was a protest against the Vietnam War. Michael performed the song on numerous TV shows including Top of the Pops and So Graham Norton. His performance of the song on Top of the Pops on 7 March 2003 was his first studio appearance on the programme since 1986. He ran into conflict with the show's producers for an anti-war, anti-Blair T-shirt worn by some members of his band. McLean stated that he was "proud of George Michael for standing up for life and sanity".[109]

When Michael's fifth studio album, Patience, was released in 2004, it was critically acclaimed and went to No. 1 on the UK Albums Chart.[14] The album became one of the fastest-selling albums in the UK, selling over 200,000 copies in the first week alone.[110] It reached the Top 5 on most European charts and peaked at No. 12 in the US, selling over 500,000 copies to earn a Gold certification from the RIAA.[15] "Amazing", the third single from the album, became a No. 1 hit in Europe.[111] When Michael appeared on The Oprah Winfrey Show on 26 May 2004, to promote the album, he performed "Amazing", along with his classic songs "Father Figure" and "Faith".[112] On the show, Michael spoke of his arrest, the public revelation of his homosexuality, and his resumption of public performances. He allowed Oprah's crew inside his home outside London.[113] The fourth single taken off the album was "Flawless". It was a dance hit in Europe as well as North America, reaching No. 1 on the Billboard Hot Dance Club Play and becoming Michael's last No. 1 single on the US Dance chart.[14] Twenty Five is Michael's second greatest hits album, celebrating the 25th anniversary of his music career.[114] Released in November 2006 by Sony BMG, it debuted at no. 1 in the UK.[115]

During the 2005 Live 8 concert at Hyde Park, London, Michael joined Paul McCartney on stage, harmonising on The Beatles classic "Drive My Car".[116] In 2006, Michael embarked on his first tour in 15 years, 25 Live. The tour began in Barcelona, Spain, on 23 September and finished in December at Wembley Arena in England.[117] On 9 June 2007, Michael became the first artist to perform live at the newly renovated Wembley Stadium in London.[118] On 25 March 2008, a third part of the 25 Live Tour was announced for North America, with 21 dates in the US and Canada.[117]

Michael made his American acting debut by playing a guardian angel to Jonny Lee Miller's character on Eli Stone, a US TV series. Each episode of the show's first season was named after a song of his. Michael also appeared on the 2008 finale show of American Idol on 21 May, singing "Praying for Time". When asked what he thought Simon Cowell would say of his performance, he replied "I think he'll probably tell me I shouldn't have done a George Michael song. He's told plenty of people that in the past, so I think that'd be quite funny."[119][120][121] On 25 December 2008, Michael released a new Christmas-themed track, "December Song (I Dreamed of Christmas)", on his website for free.[122]

2010s

In early 2010, Michael performed his first concerts in Australia since 1988.[123] On 20 February 2010, Michael performed his first show in Perth at the Burswood Dome to an audience of 15,000.[124] On 2 March 2011, Michael announced the release of his cover version of New Order's 1987 hit "True Faith" in aid of the UK charity telethon Comic Relief.[125] Michael appeared on Comic Relief itself, featuring in the first Carpool Karaoke sketch of James Corden, with the pair singing songs while Corden drove around London.[126] On 15 April 2011, Michael released a cover of Stevie Wonder's 1972 song, "You and I", as an MP3 gift to Prince William and Catherine Middleton on the occasion of their wedding on 29 April 2011. Although the MP3 was released for free download,[127] Michael appealed to those who downloaded the track to make a contribution to "The Prince William & Miss Catherine Middleton Charitable Gift Fund".[128]

The Symphonica Tour began at the Prague State Opera House on 22 August 2011.[129] In October 2011, Michael was announced as one of the final nominees for the Songwriter's Hall of Fame.[130] In November, he had to cancel the remainder of the tour as he became ill with pneumonia in Vienna, Austria, ultimately slipping into a coma.[131]

In February 2012, two months after leaving hospital, Michael made a surprise appearance at the 2012 Brit Awards at the O2 Arena in London, where he received a standing ovation, and presented Adele the award for Best British Album.[132] In March, Michael announced that he was healthy and that the Symphonica Tour would resume in autumn.[133] The final concert of the tour—which was also the final concert of Michael's life–was performed at London's Earls Court on 17 October 2012.[134]

Symphonica was released on 17 March 2014, and became Michael's seventh solo No. 1 album in the UK, and ninth overall including his Wham! chart-toppers. The album was produced by Phil Ramone and Michael; the album was Ramone's last production credit.[135] On 2 November 2016, Michael's management team announced that a second documentary on his life, entitled Freedom, was set to be released in March 2017.[136][137] A month after, English songwriter Naughty Boy confirmed plans to collaborate with Michael, for a new song and album.[138] Naughty Boy claimed that the song is "amazing but [...] bittersweet".[139] On 7 September 2017 (months after Michael's death), the single "Fantasy", featuring Nile Rodgers, was released.[140]

Having charted at number two upon its release in 1984 (behind Band Aid's "Do They Know It's Christmas?" which Michael also performed in), "Last Christmas" finally reached number-one in the UK Singles Chart on New Year's Day 2021 (chart week ending date 7 January 2021), more than 36 years after its initial release.[141] Andrew Ridgeley said the chart placing was "a testament to its timeless appeal and charm", adding: "It is a fitting tribute to George's song-writing genius... he would have been immensely proud and utterly thrilled."[141] The period of 36 years taken to reach number one was a UK chart record, which would be surpassed by Kate Bush with "Running Up That Hill" in June 2022 which took 37 years.[142]

Posthumous releases

On 7 September 2017, Michael's estate released the single "Fantasy". Written and produced by Michael, was recorded while he was working on Listen Without Prejudice Vol. 1. However, the track was not included on the album. Instead in October 1990, it was featured on the "Waiting for That Day" single in the United Kingdom and on the "Freedom! '90" single in the rest of the world.[143] On 7 September 2017, a new version reworked by Nile Rodgers was released as a single from Listen Without Prejudice / MTV Unplugged (2017).[144] The album includes the original version of "Fantasy" and the 1998 version;[145] the Nile Rodgers remix was not included on the disc but was made available to purchasers as a digital download. On 18 October 2017, a music video was released on Vevo.[146]

In 2019, the Emma Thompson-written film Last Christmas was released. The title of the film is taken from the Wham! classic. An official soundtrack album was released by Legacy Recordings on CD, two-disc vinyl, and digital formats on 8 November 2019.[147] The album contains 14 Wham! and solo George Michael songs, as well as a previously unreleased song originally completed in 2015 titled "This Is How (We Want You to Get High)".[148] The soundtrack album debuted at number one on the UK Official Soundtrack Albums Chart and at number 11 on the UK Albums Chart on 15 November 2019.[149][150] It also entered the Australian Albums Chart at number seven,[151] the Irish Albums Chart, where it debuted at number 32, climbing to number 26 the following week, and at number 55 on the US Billboard 200.[152][153]

On 22 June 2022, the documentary film Freedom Uncut was released. Michael had been working on the film shortly before his death, alongside David Austin,[154] and provides the narration throughout.[155] NME, The Guardian and Empire all praised the film and rated it 4/5 stars.[156][157][158] On 30 September 2022, a remastered and expanded version of Older was released comprising the original Older album, the Upper disc and three bonus CDs, containing remixes and live recordings of Older-era tracks.[159] The album charted at number 2 on the UK Official Albums Chart Top 100 on 7 October 2022.[160]

Personal life

Sexuality and relationships

Michael stated that his early fantasies were about women, which "led me to believe I was on the path to heterosexuality", but at puberty he started to fantasise about men, which he later said "had something to do with my environment". At the age of 19, Michael told Andrew Ridgeley that he was bisexual.[161] Michael also told one of his two sisters, but he was advised not to tell his parents about his sexuality.[162] In 1998, not long after he was outed for his sexuality, Michael said on Parkinson that he became confident he was gay when he fell in love with a man.[163] This stance was reiterated in a 1999 interview with The Advocate, where Michael told the editor-in-chief, Judy Wieder, that it was "falling in love with a man that ended his conflict over bisexuality". "I never had a moral problem with being gay", Michael told her. "I thought I had fallen in love with a woman a couple of times. Then I fell in love with a man, and realised that none of those things had been love."[164]

In 2004, Michael said, "I used to sleep with women quite a lot in the Wham! days but never felt it could develop into a relationship because I knew that, emotionally, I was a gay man. I didn't want to commit to them, but I was attracted to them. Then I became ashamed that I might be using them. I decided I had to stop, which I did when I began to worry about AIDS, which was becoming prevalent in Britain. Although I had always had safe sex, I didn't want to sleep with a woman without telling her I was bisexual. I felt that would be irresponsible. Basically, I didn't want to have that uncomfortable conversation that might ruin the moment, so I stopped sleeping with them." In the same interview, he added: "If I wasn't with Kenny [his boyfriend at the time], I would have sex with women, no question". He said he believed that the formation of his sexuality was "a nurture thing, via the absence of my father who was always busy working. It meant I was exceptionally close to my mother", though he stated that "there are definitely those who have a predisposition to being gay in which the environment is irrelevant."[161] In 2007, Michael said he had hidden his sexuality because of worries over what effect it might have on his mother.[162] Two years later, he added: "My depression at the end of Wham! was because I was beginning to realise I was gay, not bisexual."[165]

During the late 1980s, Michael had a relationship with make-up artist Kathy Jeung, who was regarded for a time as his artistic "muse" and who appeared in the "I Want Your Sex" video.[166] Michael later said that she had been his "only bona fide" girlfriend, and that she knew of his bisexuality.[161] In 2016, Jeung reacted to Michael's death by calling him a "true friend" with whom she had spent "some of the best time of [her] life".[167]

In 1992, Michael established a relationship with Anselmo Feleppa, a Brazilian dress designer whom he had met at the Rock in Rio concert in 1991. Six months into their relationship, Feleppa discovered that he was HIV-positive. Michael later said: "It was terrifying news. I thought I could have the disease too. I couldn't go through it with my family because I didn't know how to share it with them – they didn't even know I was gay."[165] In 1993, Feleppa died of an AIDS-related brain haemorrhage.[168] Michael's single, "Jesus to a Child", is a tribute to Feleppa (Michael consistently dedicated it to him before performing it live), as is his album Older (1996).[169] In 2008, speaking about the loss of Feleppa, Michael said: "It was a terribly depressing time. It took about three years to grieve, then after that I lost my mother. I felt almost like I was cursed."[170]

In 1996, Michael entered into a long-term relationship with Kenny Goss, a former flight attendant, cheerleading coach,[171] and sportswear executive from Dallas, Texas.[172] They had a home in Dallas,[173] a 16th-century house in Goring-on-Thames, Oxfordshire,[174][175] and an £8 million mansion in Highgate, North London.[168] In late November 2005, it was reported that Michael and Goss planned to register their relationship as a civil partnership in the UK,[176] but because of negative publicity and his upcoming tour, they postponed their plans.[177] On 22 August 2011, the opening night of his Symphonica Tour, Michael announced that he and Goss had split two years earlier.[178]

Michael's homosexuality became publicly known following his April 1998 arrest for public lewdness.[179] In 2007, Michael said "that hiding his sexuality made him feel 'fraudulent', and his eventual outing, when he was arrested [...] in 1998, was a subconsciously deliberate act."[180] In 2012, Michael entered a relationship with Fadi Fawaz, a Lebanese-Australian celebrity hairstylist and freelance photographer based in London.[181][182] It was Fawaz who found Michael's body on Christmas morning 2016.[183][184]

Legal troubles

On 7 April 1998, Michael was arrested for "engaging in a lewd act" in a public restroom of the Will Rogers Memorial Park in Beverly Hills, California.[185][186] Michael was arrested by undercover policeman Marcelo Rodríguez in a sting operation.[187] In an MTV interview, Michael stated: "I got followed into the restroom and then this cop—I didn't know it was a cop, obviously—he started playing this game, which I think is called, 'I'll show you mine, you show me yours, and then when you show me yours, I'm going to nick you!'"[188]

After pleading "no contest" to the charge, Michael was fined US$810 and sentenced to 80 hours of community service. Soon afterwards, Michael made a video for his single "Outside", which satirised the public toilet incident and featured men dressed as policemen kissing. Rodríguez claimed that this video "mocked" him, and that Michael had slandered him in interviews. In 1999, he brought a US$10 million court case in California against the singer. The court dismissed the case, but an appellate court reinstated it on 3 December 2002.[189] The court then ruled that Rodríguez, as a public official, could not legally recover damages for emotional distress.[190]

On 23 July 2006, Michael was again accused of engaging in anonymous public sex, this time at London's Hampstead Heath.[191] Michael stated that his cruising for anonymous sex was not an issue in his relationship with partner Kenny Goss.[192]

In February 2006, Michael was arrested for possession of Class C drugs, an incident that he described as "my own stupid fault, as usual". He was cautioned by the police and released.[193] In 2007, he pleaded guilty to drug-impaired driving after obstructing the road at traffic lights in Cricklewood in northwest London, and was subsequently banned from driving for two years and sentenced to community service.[194] On 19 September 2008, Michael was arrested in a public convenience in the Hampstead Heath area for possession of Class A and C drugs. He was taken to the police station and cautioned for controlled substance possession.[195]

In the early hours of 4 July 2010, Michael was returning from the Gay Pride parade, when he was spotted on CCTV crashing his car into the front of a Snappy Snaps store in Hampstead, north London, and was arrested on suspicion of being unfit to drive.[196][197] On 12 August, London's Metropolitan Police said he was "charged with possession of cannabis and with driving while unfit through drink or drugs".[198] It was reported that Michael had also been taking the prescription tricyclic antidepressant medication amitriptyline.[199] On 24 August 2010, the singer pleaded guilty at Highbury Corner Magistrates' Court in London after admitting driving under the influence of drugs.[200] On 14 September 2010, at the same court, Michael was sentenced to eight weeks in prison, a fine, and a five-year ban from driving.[201][202] Michael was released from Highpoint Prison in Suffolk on 11 October 2010, after serving four weeks.[203] In the dent in the shop wall Michael had crashed into, someone graffitied the word "Wham".[204]

Health

Michael struggled with substance abuse for many years.[205][206] He was arrested for drug-related offences in 2006,[193] 2008[195] and 2010.[196][197] In September 2007, on BBC Radio 4's Desert Island Discs, Michael said that his cannabis use was a problem; he wished he could smoke less of it and was constantly trying to do so.[207] On 5 December 2009, in an interview with The Guardian, Michael explained he had cut back on cannabis and was smoking only "seven or eight" spliffs per day instead of the 25 per day he had formerly smoked.[208] Michael also abused sleeping pills.[206]

On 26 October 2011, Michael cancelled a performance at the Royal Albert Hall in London due to a viral infection. On 21 November, Vienna General Hospital admitted Michael after he complained of chest pains while at a hotel two hours before his performance at a venue there for his Symphonica Tour. Michael appeared to be "in good spirits" and responded well to treatment following his admission, but on 25 November hospital officials said that his condition had "worsened overnight". This development led to cancellations and postponements of Michael's remaining 2011 performances, which had been scheduled mainly for the United Kingdom.[209] The singer was later confirmed to have suffered from pneumonia and, until 1 December, was in an intensive care unit; at one point, he was comatose. On 21 December, the hospital discharged him. Michael told the press that he had undergone a tracheotomy,[210] that the staff at the hospital had saved his life, and that he would perform a free concert for them.[211] After waking from the coma, Michael had a temporary West Country accent, and there was concern he had developed foreign accent syndrome.[212]

On 16 May 2013, Michael sustained a head injury in a car accident on the M1 motorway, near St Albans in Hertfordshire and was airlifted to hospital.[213][214] On 29 May, Michael's publicist confirmed that he had left the hospital and that his injuries were superficial.[215] In 2014, Michael stated that he had refrained from using cannabis for one-and-one-half years. In June 2015, he checked into a drug rehabilitation facility in Switzerland.[216]

Politics

"To call us Thatcherite was so simplistic, basically saying that if you've got a deep enough tan and made a bit of money then you've got to be a Thatcherite."

— Michael, a Labour voter throughout the 1980s, distancing himself from Thatcher's Conservative Party.[217]

Michael's father was a communist. At the age of fifteen, Michael joined the Young Communist League, under his Greek name.[218] During the time of Margaret Thatcher as the Conservative Prime Minister of the United Kingdom throughout the 1980s, Michael voted Labour.[217] In September 1984, Wham! performed at a benefit concert at London's Royal Festival Hall for the striking UK miners.[219]

In 2000, Michael joined Melissa Etheridge, Garth Brooks, Queen Latifah, Pet Shop Boys, and k.d. lang, to perform in Washington, D.C. as part of Equality Rocks, a concert to benefit the Human Rights Campaign,[220] an American LGBT rights group. His 2002 single "Shoot the Dog" was critical of the friendly relationship between the UK and US governments, in particular the relationship between Tony Blair and George W. Bush, with their involvement in the War on Terror.[221] Michael voiced his concern about the lack of public consultation in the UK regarding the War on Terror: "On an issue as enormous as the possible bombing of Iraq, how can you represent us when you haven't asked us what we think?"[221]

In 2006, Michael performed a free concert for NHS nurses in London to thank the nurses who had cared for his late mother. He told the audience: "Thank you for everything you do — some people appreciate it. Now if we can only get the government to do the same thing."[222]

In 2007, Michael sent the £1,450,000 piano that John Lennon used to write "Imagine" around the United States on a "peace tour", displaying at places where notable acts of violence had taken place, such as Dallas' Dealey Plaza, where US President John F. Kennedy had been shot.[223] He devoted his 2007 concert in Sofia, from his "Twenty Five Tour" to the Bulgarian nurses prosecuted in the HIV trial in Libya.[224] On 17 June 2008, Michael said he was thrilled by California's legalisation of same-sex marriage, calling the move "way overdue".[225]

Philanthropy

In November 1984, Michael joined other British and Irish pop stars of the era to form Band Aid, singing on the charity song "Do They Know It's Christmas?" for famine relief in Ethiopia. This single became the UK Christmas number one in December 1984, holding Michael's own song, "Last Christmas" by Wham!, at No. 2.[226] "Do They Know It's Christmas?" sold 3.75 million copies in the UK and became the biggest-selling single in UK chart history, a title it held until 1997 when it was overtaken by Elton John's "Candle in the Wind 1997", released in tribute to Princess Diana following her death (Michael attended Diana's funeral with Elton John).[226] Michael donated the royalties from "Last Christmas" to Band Aid and subsequently sang with Elton John at Live Aid (the Band Aid charity concert) in 1985.[227]

In 1986, Michael took part in the Prince's Trust charity concert held at Wembley Arena, performing "Everytime You Go Away" alongside Paul Young.[228] In 1988, Michael participated in the Nelson Mandela 70th Birthday Tribute at Wembley Stadium in London together with many other singers (such as Annie Lennox and Sting), performing "Sexual Healing".[229]

An LGBT rights campaigner and HIV/AIDS charity fundraiser,[230][231][232] the proceeds from the 1991 single "Don't Let the Sun Go Down on Me" were divided among 10 different charities for children, AIDS and education. He was also a patron of the Elton John AIDS Foundation.[233] Michael wore a red ribbon at the Freddie Mercury Tribute Concert at Wembley Stadium in April 1992.[234][235] He was instrumental in bringing the compilation CD Red Hot + Dance to fruition, contributing three original songs, with the album featuring Seal and Madonna among others.[236]

In 2003, he paired up with Ronan Keating on the UK edition of the game show Who Wants to Be a Millionaire? and won £32,000, after having their original £64,000 winnings halved by answering the £125,000 question incorrectly.[237][238] The same year, Michael joined other celebrities to support a campaign to help raise £20 million for terminally ill children run by the Rainbow Trust Children's Charity of which he was a patron. He said: "Loss is such an incredibly difficult thing. I bow down to people who actually have to deal with the loss of a child."[239]

From 2005 until his death, Michael was a patron of the Swan Lifeline charity. At the time he had moved to his home in Highgate, he had swans in the river at the end of his garden. A neighbour, who was involved with the charity, asked him if he would be interested, and he immediately agreed.[242][243][244]

Following Michael's death, various charities revealed that Michael had privately supported them for many years. Those charities included Childline (to whom he had donated "millions"),[245][218] the Terrence Higgins Trust, and Macmillan Cancer Support.[246] Michael also donated to individuals: he reportedly called the production team of the quiz show Deal or No Deal after a contestant had revealed that she needed £15,000 to fund IVF treatment and anonymously paid for the treatment.[246] Michael once tipped a student nurse working as a barmaid £5,000 because she was in debt.[247] On 3 January 2017, another woman came forward and (with the permission of Michael's family) revealed he had anonymously paid for her IVF treatment after seeing her talk about her problems conceiving on an episode of This Morning in 2010. The woman gave birth to a girl in 2012.[248]

After his death, it was also revealed that Michael had been anonymously paying for an annual Christmas tree erected where he lived in Highgate, as well as funding the Christmas lights, for the previous decade. He was also the largest funder of Highgate's annual Fair in the Square for those ten years, donating anonymously as "a local resident".[249][250]

Assets

Between 2006 and 2008, according to reports, Michael earned £48.5 million from the 25 Live tour alone.[251] In July 2014, he was reported to have been a celebrity investor in a tax avoidance scheme called Liberty.[252] According to the Sunday Times Rich List 2015 of the wealthiest British musicians, Michael was worth £105 million.[253]

Death

In the early hours of Christmas Day 2016, Michael died in bed at his home in Goring-on-Thames, at the age of 53. He was found by his partner, Fadi Fawaz.[183][184][254] In March 2017, a senior coroner in Oxfordshire attributed Michael's death to natural causes due to dilated cardiomyopathy with myocarditis and a fatty liver.[255][256][257][258]

Owing to the delay in determining the cause of death, Michael's funeral was held on 29 March 2017. In a private ceremony, he was buried at Highgate Cemetery in north London, on one side of his mother's grave.[259] His sister Melanie, who died after him three years to the day, is buried on the other side.[260]

Aftermath

In the summer of 2017, a temporary informal memorial garden was created outside Michael's former home in The Grove, Highgate. The site, in a private square that Michael had owned, was tended by fans for approximately eighteen months until it was cleared.[261]

In March 2019, Michael's art collection was auctioned in England for £11.3 million. The proceeds were donated to various philanthropic organisations Michael gave to while he was alive.[262]

Michael's will left most of his £97 million estate to his sisters, his father and friends. It did not include bequests to either Fawaz or to his former partner, Kenny Goss. In 2021, following legal proceedings, the trustees of Michael's estate entered into a financial settlement with Goss.[263]

Tributes

Elton John was among those who paid tribute to Michael, emotionally addressing the audience in Las Vegas on 28 December, "What a singer, what a songwriter. But more than anything as a human being he was one of the kindest, sweetest, most generous people I've ever met."[264]

At the 59th Annual Grammy Awards on 12 February 2017, Adele performed a slow version of "Fastlove" in tribute to Michael.[265] On 22 February, Coldplay lead singer Chris Martin performed "A Different Corner" at the 2017 Brit Awards.[266] In June, Michael's close friend, former Spice Girls member Geri Halliwell, released a charity single, "Angels in Chains", a tribute to him, to raise money for Childline.[267]

In 2020, Michael was commemorated with a mural in his native borough of Brent.[268] The artwork, which formed part of the Brent Biennial, was commissioned to pay tribute to his contribution to the fields of music and entertainment.[269] Artist Dawn Mellor said it celebrates the singer as a pioneering cultural and LGBTQ+ figure.[270] In February 2024, the Royal Mint unveiled a collectable coin featuring Michael wearing his trademark sunglasses.[271]

Awards and achievements

Michael won numerous music awards throughout his 30-year career, including three Brit Awards—winning Best British Male Artist twice, four MTV Video Music Awards, six Ivor Novello Awards, three American Music Awards (including two in the traditionally-black Soul/R&B category[272][273]), and two Grammy Awards from eight nominations.[274][275] In 2015, he was ranked 45th in Billboard's list of the "Greatest Hot 100 Artists of All Time".[276] The Radio Academy stated that Michael was the most frequently played artist on British radio during the period 1984–2004.[10] In 2019, Michael was named as the greatest artist of all time by Smooth Radio.[277] In 2023, Michael was nominated for induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.[278] On 3 May 2023, Michael was selected as an inductee to the 2023 class alongside Kate Bush, Willie Nelson, The Spinners, Missy Elliott and Rage Against the Machine.[279][280] In November 2023, Michael was inducted into the Hall, with Andrew Ridgeley as his induction presenter.[281]

Discography and record sales

At the time of his death, Michael was estimated to have sold between 100 million and 125 million records worldwide.[282][283][4] As a solo artist, he is estimated to have sold over 100 million records, making him one of the best-selling music artists.[282] He is estimated to have sold up to 30 million records with Wham!.[284] His debut solo album Faith sold more than 25 million copies.[285]

Solo discography

- Faith (1987)

- Listen Without Prejudice Vol. 1 (1990)

- Older (1996)

- Songs from the Last Century (1999)

- Patience (2004)

Wham! discography

- Fantastic (1983)

- Make It Big (1984)

- Music from the Edge of Heaven (1986)

Tours

- The Faith Tour (1988–89)

- Cover to Cover (1991)

- 25 Live (2006–08)

- George Michael Live in Australia (2010)

- Symphonica Tour (2011–12)

See also

- Imagine Piano Peace Project

- List of artists by number of UK Singles Chart number ones

- List of artists who reached number one in the United States

- List of best-selling music artists

- Panayiotou v Sony Music Entertainment (UK) Ltd.

References

- ^ "George Michael". Desert Island Discs. 5 October 2007. BBC Radio 4. Archived from the original on 27 February 2015. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ^ "George Michael: Chart topper and cultural icon dead at 53". CNN. 26 December 2016. Archived from the original on 23 October 2021. Retrieved 3 March 2024.

- ^ "Troubled personal life of pop superstar George Michael". Sky News. 27 December 2016. Archived from the original on 26 December 2016. Retrieved 27 December 2016.

- ^ a b "KEEPING FAITH! WARNER CHAPPELL MUSIC RENEWS PUBLISHING DEAL WITH GEORGE MICHAEL'S ESTATE" (Press release). PR Newswire. Archived from the original on 3 February 2023. Retrieved 3 February 2023.

- ^ a b Rubiner, Julia (1993). Contemporary Musicians: Profiles of the People in Music, Volume 9. Gale Research, Incorporated. p. 169.

As a solo artist George Michael has been hailed as a leading creative force in popular songwriting. With fame approaching, Michael decided to change his name from the intimidating Georgios Panayiotou to the more accessible George Michael.

- ^ "The 20 best male singers of all time, ranked in order of pure vocal ability". Smooth Radio. 9 April 2020. Archived from the original on 23 October 2021. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ "George Michael's Style: Remembering His Top 5 Iconic Looks". Billboard. 27 December 2016. Archived from the original on 26 October 2021. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- ^ "Pop icon George Michael was a music video master". Mashable. 25 December 2016. Archived from the original on 26 October 2021. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- ^ "The 200 Greatest Singers of All Time". Rolling Stone. 1 January 2023. Archived from the original on 3 August 2023. Retrieved 3 August 2023.

- ^ a b "George Michael dominates airwaves" Archived 19 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine. BBC. Retrieved 17 February 2018.

- ^ "Rock and Roll Hall of Fame 2023 Inductees". The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on 5 May 2023. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Hatton, Celia (9 April 2015). "When China woke up to Wham!". BBC. Archived from the original on 19 August 2018. Retrieved 10 April 2015.

- ^ a b c Patrick, Al (28 April 1985). "East meets Wham!, and another great wall comes down". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 12 April 2020. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q "George Michael". The Official Charts Company. Retrieved 21 April 2011. Archived 2 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l George Michael Album & Song Chart History Billboard. Retrieved 21 April 2011

- ^ "George Michael Chart History". Billboard. Archived from the original on 9 June 2019. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- ^ Biography George Michael: The Making of a Superstar Bruce Dessau, London: Sidgwick & Jackson, 1989

- ^ "George Michael-The history". Twentyfive Live LLP. & Signatures Network. Archived from the original on 13 September 2008. Retrieved 5 February 2010.

- ^ a b A Different Story; George Michael Biographical DVD

- ^ Jovanovich, Rob (2008). George Michael - the Biography. Piatkus Books. p. 13.

- ^ a b "George Michael's sister Melanie Panayiotou is found dead on Christmas Day aged 59". BBC News. 27 December 2019. Archived from the original on 5 October 2021. Retrieved 14 October 2021.

- ^ "The true story of George Michael's complicated relationship with his mother". TODAY.com. 29 June 2022. Archived from the original on 27 September 2023. Retrieved 9 October 2023.

- ^ "Lesley Angold Panayiotou: What Happened To George Michael's Mother?". Dicy Trends. 8 July 2023. Archived from the original on 24 October 2023. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- ^ "Obituary: George Michael". BBC News. 25 December 2016. Archived from the original on 26 December 2016. Retrieved 26 December 2016.

- ^ Powers, Ann (14 June 2008). "George Michael embraces his dualities". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 31 July 2015.

- ^ "George Michael: the superstar who doesn't take life too seriously" Archived 31 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine. The Guardian. Retrieved 8 May 2014

- ^ Bruce Dessau (1989). "George Michael: the making of a superstar". p. 8. Sidgwick & Jackson

- ^ "George Michael's family in bedside vigil as star battles severe pneumonia" Archived 26 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine. The Telegraph. Retrieved 27 December 2016

- ^ "George Michael: Bang of the head turned me to music". Irish Examiner. Archived from the original on 25 August 2021. Retrieved 25 August 2021.

- ^ "Following in the footsteps of George Michael in London". forunitedkingdomlovers.uk. 25 June 2021. Archived from the original on 9 July 2023. Retrieved 9 July 2023.

- ^ Negus, Keith; Sledmere, Adrian (May 2022). "Postcolonial paths of pop: a suburban psychogeography of George Michael and Wham!". Popular Music. 41 (2): 131–151. doi:10.1017/S0261143022000253. ISSN 0261-1430. S2CID 249829672. Archived from the original on 9 July 2023. Retrieved 9 July 2023. PDF Archived 9 July 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "George Michael plaque unveiled at Bushey Meads school". BBC News. 16 April 2018. Archived from the original on 9 July 2023. Retrieved 9 July 2023.

- ^ A Night At The Opera Archived 10 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine QueenZone.com. Retrieved 23 January 2013

- ^ "Belair Restaurant in Northwood". Watford Observer. 20 January 2003. Archived from the original on 29 July 2023. Retrieved 9 July 2023.

- ^ Gavin, James (28 June 2022). George Michael: A Life. Abrams. p. 21. ISBN 978-1-64700-673-0. Archived from the original on 16 July 2023. Retrieved 22 April 2024.

- ^ Ridgeley, Andrew (8 October 2019). Wham!, George Michael and Me: A Memoir. Penguin. pp. 120, 136, 141. ISBN 978-1-5247-4531-8. Archived from the original on 16 July 2023. Retrieved 22 April 2024.

- ^ Youngs, Ian (26 December 2016). "George Michael: Six songs that defined his life". BBC News. Archived from the original on 3 October 2020. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- ^ Michael, George; Goodall, Nigel (1999). George Michael: In His Own Words. Omnibus Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-7119-7891-1. Archived from the original on 9 February 2023. Retrieved 12 March 2016.

- ^ Rachel, Aroesti (14 December 2017). "Still saving us from tears: the inside story of Wham!'s Last Christmas". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 22 December 2017. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- ^ "The Ivors 1985" Archived 9 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine. The Ivors. Retrieved 8 January 2018

- ^ "Flashback: Band Aid Raises Millions With 'Do They Know It's Christmas?'". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 27 November 2021. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- ^ "The philanthropic acts of George Michael: from £5k tips to nurses' gigs". The Guardian. 7 January 2018. Archived from the original on 18 October 2020. Retrieved 7 January 2018.

- ^ "George Michael: 20 Essential Songs". Rolling Stone. 7 January 2018. Archived from the original on 8 January 2018. Retrieved 7 January 2018.

- ^ Litchfield, David (1985). "David Cassidy by George Michael". Ritz Newspaper No. 100. Bailey & Litchfield. pp. 16–19.

- ^ a b "How Wham! baffled Chinese youth in first pop concert". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 25 October 2019. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- ^ Wham! in China – Foreign Skies Movie Reviews Archived 6 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 21 April 2011

- ^ "How Wham! made Lindsay Anderson see red in China". The Independent. Archived from the original on 5 August 2021. Retrieved 5 August 2021.

- ^ Wham! Number Ones Archived 18 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine Number-ones.co.uk. Retrieved 21 April 2011

- ^ Bego, Mark (10 February 2010). Aretha Franklin: The Queen of Soul. Hachette Books. p. 249. ISBN 978-0-7867-5229-4.

- ^ Lucy Ellis, Bryony Sutherland (1998) The complete guide to the music of George Michael & Wham! p. 37. Music Sales Group, 1998

- ^ "Aretha Franklin Timeline". The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum, 2010. Retrieved 21 April 2011

- ^ a b George Michael: I Want Your Sex – Banned Songs – Music Archived 1 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine Virgin Media, 27 January 2010. Retrieved 21 April 2011

- ^ Sexy Song of the Week: "I Want Your Sex" Archived 7 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine ANT 2301: Human Sexuality & Culture, Gravlee.org; University of Florida. Retrieved 21 April 2011

- ^ Video Review Archived 9 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine George Michael – The Box of Fame, 15 January 2005. Retrieved 21 April 2011

- ^ a b 80s Singers: George Michael Total 80s Remix, 22 February 1999. Retrieved 21 April 2011.

- ^ a b George Michael – Gay Icons Archived 7 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine AstaBGay.com. Retrieved 21 April 2011

- ^ George Michael Biography Archived 9 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine LoveToKnow Music. Retrieved 21 April 2011

- ^ McCormick, Neil "George Michael's image will outlast the scandal" Archived 10 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine. The Daily Telegraph (London), 15 September 2010. Retrieved 21 April 2011

- ^ George Michael|80s Singers. Total 80s Remix, 22 February 1999. Retrieved 21 April 2011

- ^ RIAA Certified Diamond Albums Archived 28 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine HBR Production. Retrieved 21 April 2011

- ^ "George Michael at HP Pavilion at San Jose". Yahoo!. 24 March 2008. Archived from the original on 2 June 2008. Retrieved 3 May 2008.

- ^ Huey, Steve (30 October 1987). "Faith – George Michael : Songs, Reviews, Credits, Awards". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 5 December 2012. Retrieved 17 December 2012.

- ^ Coleman, Mark (14 January 1988). "Faith | Album Reviews". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 26 April 2011. Retrieved 17 December 2012.

- ^ George Michael – Faith Remaster Archived 20 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine antiMusic.com, 12 April 2011. Retrieved 21 April 2011

- ^ Entries – Monsters of Rock / OU812 Tour The Van Halen Encyclopedia. Retrieved 21 April 2011

- ^ "1988 Grammy Award Winners". National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on 28 July 2013. Retrieved 14 December 2014.

- ^ 1989 MTV Video Music Awards: Video Vanguard Award Archived 6 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine MTV. Retrieved 7 December 2011

- ^ "George Michael: A Different Story Review". Empire. Archived from the original on 29 October 2018. Retrieved 28 October 2018.

- ^ a b George Michael Archived 18 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine NewMagic949.com. Retrieved 21 April 2011

- ^ a b Listen Without Prejudice Archived 5 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine Teen Ink. Retrieved 21 April 2011

- ^ a b "UK Charts > George Michael". The Official Charts Company. Retrieved 5 March 2011.

- ^ "George Michael: 50 years in numbers" Archived 26 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine. The Daily Telegraph (London). Retrieved 15 December 2014

- ^ Hunter, James (4 October 1990). "Listen Without Prejudice Vol. 1 | Album Reviews". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 16 October 2007. Retrieved 17 December 2012.

- ^ a b SoulBounce's Class Of 1990: George Michael 'Listen Without Prejudice Vol. I' Archived 10 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine Soulbounce.com, 29 November 2010. Retrieved 21 April 2011

- ^ Listen Without Prejudice Vol. 1 Entertainment Weekly, 14 September 1990. Retrieved 21 April 2011

- ^ Gay History, Gay Celebrities, Gay Icons – George Michael Archived 21 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine Circa-club.com. Retrieved 21 April 2011

- ^ a b Reviews/Pop; George Michael's Tour, From Motown to Disco Archived 19 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine The New York Times, 28 October 1991. Retrieved 21 April 2011

- ^ Ellis, Lucy; Sutherland, Bryony (1998). The Complete Guide to the Music of George Michael & Wham!. Omnibus Press. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-7119-6822-6. Archived from the original on 9 February 2023. Retrieved 12 March 2016.

- ^ Michael, George; Parsons, Tony (15 July 1991). Bare: George Michael, His Own Story. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-013235-9.

- ^ Cope, Michael (24 October 1993). "Inside Story: Sony faces a test of faith: George Michael, who has cast off the leather look for a suit and horn-rimmed glasses, went to court last week for a divorce from his Japanese bosses, Norio Ohga, below left, and Akio Morita. No matter who wins, writes Nigel Cope, the case will put a different spin on the record business". The Independent. Archived from the original on 16 September 2015. Retrieved 29 December 2016.

- ^ George Michael Gay Life, About.com. Retrieved 21 April 2011

- ^ Blake, Mark (22 March 2011). Is This the Real Life?: The Untold Story of Queen. Hachette Books. p. 364. ISBN 978-0-306-81973-5. Archived from the original on 9 February 2023. Retrieved 14 December 2014.

- ^ Freddie Mercury Tribute Concert for AIDS Awareness Archived 17 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine MyGnR.com. Retrieved 21 April 2011

- ^ The Freddie Mercury Tribute: Concert for AIDS Awareness Cineman. Retrieved 21 April 2011

- ^ a b Queen's Greatest Hits 3 Archived 27 September 2020 at the Wayback Machine h2g2, BBC, 22 March 2005. Retrieved 21 April 2011

- ^ a b Queen Greatest Vol 3 Archived 26 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine AlbumLinerNotes.com, 17 January 1997. Retrieved 21 April 2011

- ^ "Queen's Roger Taylor: George Michael 'Wouldn't Have Suited' Band". Ultimate Classic Rock. Archived from the original on 28 February 2021. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ Five Live (George Michael and Queen EP). AllMusic.

- ^ 5 Live / Freddie Mercury Tribute Concert Archived 1 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine Shanes Queen Site. Retrieved 21 April 2011

- ^ Queen - Greatest Hits III. Allmusic. Retrieved 23 September 2021

- ^ Pride, Dominic (10 December 1994). "MTV Euro Awards Get Mixed Response". Billboard. pp. 18–. ISSN 0006-2510. Archived from the original on 9 February 2023. Retrieved 21 April 2011.

- ^ Part one Chez Nobby, Fortunecity. Retrieved 21 April 2011

- ^ "George Michael's 'Older' Turns 25 | Anniversary Retrospective". Albumism. 12 May 2021. Archived from the original on 3 October 2021. Retrieved 14 October 2021.

- ^ "Making George Michael: Older". 19 July 2021. Archived from the original on 28 October 2021. Retrieved 14 October 2021.

- ^ "1996 MTV Europe Awards". MetroLyrics.com. 14 November 1996. Archived from the original on 22 October 2012. Retrieved 21 April 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ The Brit Awards Archived 19 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine everyHit.com. Retrieved 21 April 2011

- ^ "George Michael – Star Snapshot". Femail.com.au. 27 April 2009. Archived from the original on 10 May 2010. Retrieved 27 April 2009.

- ^ George Michael on Archived 22 December 2009 at the Wayback Machine TV.com, 20 December 2008. Retrieved 21 April 2011

- ^ George Michael's Suicidal Thoughts After Mother's Death Archived 17 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine popdirt.com, 10 September 2004. Retrieved 21 April 2011

- ^ George Michael goes back to Sony Archived 6 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine BBC News, 17 November 2003. Retrieved 21 April 2011

- ^ "BPI Highest Retail Sales" (PDF). British Phonographic Industry. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 November 2009. Retrieved 17 January 2011.

- ^ Artist: George Michael Hip Online Archived 15 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Halstead, Craig; Cadman, Chris (1 January 2003). Michael Jackson the Solo Years. Authors on Line Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7552-0091-7. Archived from the original on 9 February 2023. Retrieved 26 December 2016.

- ^ "Whitney, George Michael To Team For Duet". MTV News. Archived from the original on 26 December 2016. Retrieved 26 December 2016.

- ^ George Michael Freeek! Archived 6 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine Top40-charts.com. Retrieved 21 April 2011.

- ^ George Michael's highs and lows Archived 4 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine BBC News, 21 September 2008. Retrieved 21 April 2011

- ^ "George Goes Political The Daily Mirror, July 1, 2002". george.michael.szm.com/. July 2002. Archived from the original on 5 September 2021. Retrieved 5 September 2021.

- ^ George Michael Shoot The Dog Archived 6 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine Top40-charts.com. Retrieved 21 April 2011

- ^ "Michael accuses BBC in war row". BBC News. 7 March 2003. Archived from the original on 1 January 2017. Retrieved 26 December 2016.

- ^ Analysis: UK albums and singles market Archived 8 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine Music Week, 29 November 2004. Retrieved 21 April 2011

- ^ George Michael Amazing Archived 7 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine Top40-charts.com. Retrieved 21 April 2011

- ^ "George Michael's Oprah Winfrey Show Interview (2004)". GM Forever. 7 May 2019. Archived from the original on 9 February 2023. Retrieved 25 April 2021.

- ^ Inside George Michael's Home Archived 23 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine Oprah.com, 1 January 2006. Retrieved 21 April 2011

- ^ George Michael – Twentyfive CD Album Archived 17 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine CD Universe, 28 November 2006. Retrieved 21 April 2011

- ^ Number 1 albums of the 2000s Archived 16 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine everyHit.com, 16 March 2000. Retrieved 21 April 2011

- ^ "George Michael Dead: Photos of His Life". Billboard. 26 December 2016. Archived from the original on 17 April 2020. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- ^ a b "George Michael plays "final" major shows" Archived 3 December 2021 at the Wayback Machine. The Independent. Monday 25 August 2008

- ^ "Michael makes history at Wembley" Archived 24 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine. BBC News. Retrieved 8 April 2015

- ^ "George Michael Regains His Faith". AOL Music Canada. 2008. Archived from the original on 31 May 2008. Retrieved 13 June 2008.

- ^ 24 Facts: George Michael Archived 8 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine Channel 24, 14 October 2010

- ^ George Michael Reflects on His Own American Idolatry Spinner, 22 May 2008

- ^ "New George Michael Track Survives on The Pirate Bay". TorrentFreak. 27 December 2008. Archived from the original on 23 June 2010. Retrieved 27 April 2009.

- ^ "2010 Australian Tour Announcement". GeorgeMichael.com. 24 November 2009. Archived from the original on 28 November 2009. Retrieved 24 November 2009.

- ^ "George Michael on Australian stage". Herald Sun. 21 February 2010. Archived from the original on 27 September 2020. Retrieved 22 February 2010.

- ^ George Michael covers New Order's 'True Faith' for Comic Relief Archived 13 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine NME, 2 March 2011. Retrieved 21 April 2011

- ^ "George Michael in 'first' Carpool Karaoke". BBC. 26 December 2016. Archived from the original on 29 December 2016. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ^ George Covers Stevie Wonder for Will & Kate Archived 2 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine GeorgeMichael.com, 15 April 2011

- ^ Fazackarley, Jane (16 April 2011). "George Michael releases Royal Wedding song". Digital Spy. Archived from the original on 13 January 2017. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ Walsh, Ben (23 August 2011). "First Night: George Michael – Symphonica Tour, State Opera House, Prague". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 1 December 2011. Retrieved 23 August 2011.

- ^ "Songwriters Hall of Fame 2012 Nominees For Induction Announced" (Press release). Songwriters Hall of Fame. 18 October 2011. Archived from the original on 18 October 2011. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- ^ "George Michael's condition worsened overnight say doctors". Vienna Times. Archived from the original on 27 November 2011. Retrieved 31 December 2011.

- ^ "2012 BRIT Awards" Archived 5 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine. London Evening Standard. Retrieved 16 December 2014

- ^ Usmar, Jo (20 March 2012). "George Michael reschedules cancelled tour dates after beating pneumonia". Daily Mirror. Archived from the original on 13 February 2018. Retrieved 13 February 2018.

- ^ "Flashback: George Michael Plays Final Encore at Last Concert". Rolling Stone. 21 March 2018. Archived from the original on 21 March 2018. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- ^ "George Michael beats Kylie to top album chart". BBC. 23 February 2014. Archived from the original on 29 October 2018. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ^ : "George Michael on Instagram". Instagram. Archived from the original on 23 December 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2017.

- ^ "George Michael Dead: Star Had Promised Comeback Album For 2017, And Film 'Freedom' About Sony Court Battle" Archived 27 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine. The Huffington Post. Retrieved 27 December 2016

- ^ "George Michael planned to release new album in 2017". NME. 26 December 2016. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 22 January 2017.

- ^ "Naughty Boy 'won't rule out' releasing his George Michael collaboration". BBC Newsbeat. 19 January 2017. Archived from the original on 13 February 2017. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ^ Beaumont-Thomas, Ben (7 September 2017). "George Michael's new single Fantasy – a rework full of sex, funk and fabulousness". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 10 October 2017.

- ^ a b Beaumont-Thomas, Ben (1 January 2021). "Last Christmas by Wham! reaches No 1 for first time after 36 years". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 1 January 2021. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- ^ "Kate Bush's Running Up That Hill is Official Charts Number 1 Single: Singer becomes 3 x Official Charts Record Breaker with Stranger Things success". Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on 17 June 2022. Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- ^ Ben Beaumont-Thomas (7 September 2017). "George Michael's new single Fantasy – a rework full of sex, funk and fabulousness". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 17 October 2017.

- ^ Jon Blistein (7 September 2017). "Encore Hear George Michael's Posthumous 'Fantasy' Remake With Nile Rodgers". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 17 October 2017. Retrieved 17 October 2017.

- ^ "Listen Without Prejudice / MTV Unplugged (Region Free) Box set". Amazon UK. Archived from the original on 18 October 2017. Retrieved 17 October 2017.

- ^ "George Michael - Fantasy (Official Video) ft. Nile Rodgers". 18 October 2017. Archived from the original on 11 November 2022. Retrieved 11 November 2022 – via YouTube.

- ^ Kaufman, Gil (4 October 2019). "'Last Christmas' Soundtrack Track List: See It Here". Billboard. Archived from the original on 9 May 2021. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ Savage, Mark (6 November 2019). "George Michael: Upbeat new song premieres on Radio 2". BBC. Archived from the original on 6 November 2019. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "Official Soundtrack Albums Chart Top 50". Official Charts Company. 15 November 2019. Archived from the original on 24 February 2015. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- ^ "Official Albums Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. 15 November 2019. Archived from the original on 30 August 2018. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- ^ "ARIA ALBUMS CHART" (PDF). ARIA Charts. 11 November 2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 November 2022. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "Official Irish Albums Chart Top 50". Official Charts Company. November 2019. Archived from the original on 30 August 2020. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- ^ "Billboard 200". Billboard. November 2019. Archived from the original on 2 July 2011. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "George Michael Preferred Music to Fame. The Doc He Made Does, Too". The New York Times. 22 June 2022. Archived from the original on 11 November 2022. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ Davda, Rishi (15 June 2022). "Never-before-seen footage of George Michael in new film Freedom Uncut". ITV. Archived from the original on 11 November 2022. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ Levine, Nick (22 June 2022). "'George Michael Freedom Uncut' review: he's still a fascinating mass of contradictions". NME. Archived from the original on 11 November 2022. Retrieved 11 November 2022.