Cody Wilson

Cody Wilson | |

|---|---|

Wilson in 2023 | |

| Born | January 31, 1988 |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | University of Central Arkansas (B.A., 2010) |

| Known for | Defense Distributed |

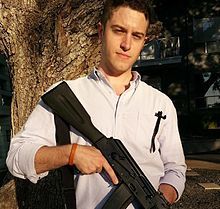

Cody Rutledge Wilson (born January 31, 1988) is an American gun rights activist and crypto-anarchist.[1][2] He started Defense Distributed, a non-profit organization which develops and publishes open source gun designs, so-called "wiki weapons" created by 3D printing and digital manufacture.[3][4] Defense Distributed gained international notoriety in 2013 when it published plans online for the Liberator, the first widely available functioning 3D-printed pistol.[5]

Career

[edit]Defense Distributed

[edit]

In 2012, Wilson and associates at Defense Distributed began the Wiki Weapon Project to raise funds for designing and releasing the files for a 3D printable gun.[6] At the time Wilson was the project's only spokesperson; he called himself "co-founder" and "director."[7]

Learning of Defense Distributed's plans, manufacturer Stratasys threatened legal action and demanded the return of a 3D printer it had leased to Wilson. On September 26, 2012, before the printer was assembled for use, Wilson received an email from Stratasys suggesting he was using the printer "for illegal purposes". Stratasys immediately canceled its lease with Wilson and sent a team to confiscate the printer.[8][9]

While visiting the office of the ATF in Austin, Texas to inquire about the legalities of his project, Wilson was interrogated by the officers there.[8] Six months later, he was given a Federal Firearms License (FFL) to manufacture and deal weapons.[10]

In May 2013, Wilson successfully test-fired a pistol called "the Liberator" which reportedly was made using a Stratasys Dimension series 3D printer purchased on eBay.[11] After test firing, he released the blueprints of the gun's design online through a Defense Distributed website.[12] The State Department Office of Defense Trade Controls Compliance demanded that he remove the files, threatening prosecution for violations of the International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR).[13] In October 2014, Defense Distributed began selling to the public a miniature CNC (computer numerical control) mill named Ghost Gunner to finish "80 percent" receivers, like those used to build the AR-15 semi-automatic rifle.[14][15]

In November 2014 Wilson was named to the Forbes 30 Under 30 list,[16] a pick the publication regretted nine years later putting Wilson in its Hall of Shame.[17][18] On May 6, 2015, Defense Distributed and the Second Amendment Foundation filed Defense Distributed v. U.S. Dept. of State, a lawsuit (a constitutional challenge of the ITAR regime used to control speech.[19] On July 10, 2018, the State Department offered to settle the lawsuit and Wilson continued to work at DEFCAD.[20] Wilson briefly resigned from the company in 2018 after being indicted for sexual assault.[21] In September 2019, after accepting a plea deal and probation, he rejoined the company.[22][23]

Dark Wallet

[edit]In 2013, Wilson, along with Amir Taaki, began work on a Bitcoin cryptocurrency wallet called Dark Wallet, a project planned to anonymize financial transactions.[24][25][26] He appeared at the SXSW festival in Austin in 2014 to discuss Dark Wallet.[27]

Bitcoin Foundation

[edit]On U.S. election day, November 4, 2014, Wilson announced that he would stand for election to a seat on the board of directors of the Bitcoin Foundation, with "the sole purpose of destroying the Foundation." He said, "I will run on a platform of the complete dissolution of the Bitcoin Foundation and will begin and end every single one of my public statements with that message."[28]

Hatreon

[edit]In 2017, Wilson launched Hatreon.us, an "alt-right version of Patreon" providing crowdfunding and payment services for groups and individuals banned from platforms including Kickstarter, Patreon, PayPal, and Stripe.[29] The site attracted notable alt-right and neo-Nazi figures such as Andrew Anglin and Richard B. Spencer. Wilson said that Hatreon clients included "right-wing women, people of color, and transgender people"; Bloomberg News reported that most donations went to white supremacists.[30] According to Hannah Shearer, staff attorney at the Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence, Hatreon users incited violence contrary to Hatreon's terms of service, which forbid illegal activity.[30][31]

Hatreon.us claimed to have received about $25,000 a month in donations.[32] The site took a five percent cut of donations.[30] Several months after Hatreon's launch, Visa, the site's payments processor, suspended its financial services. With no means of processing payments, the site became inactive.[33][34]

Political and economic views

[edit]Wilson claims an array of influences from anti-state and libertarian political thinkers[35] including mutualist theorist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon,[11][36] paleolibertarian anarcho-capitalists like Austrian School economist Hans-Hermann Hoppe, and classical liberals such as Frederic Bastiat.[37][35] His political thought has been compared to the "conservative revolutionary" ideas of Ernst Jünger. Jacob Siegel wrote that "Cody Wilson arrives at a place where left, right—and democracy—disappear" and that he oscillates "somewhere between anarch and anarchist".[38]

Wilson is an avowed crypto-anarchist, and has discussed his work in relation to the cypherpunks and Timothy May's vision.[39] He did not vote in the 2016 United States presidential election.[40] He frequently cites the work of post-Marxist thinkers in public comments, especially that of Jean Baudrillard, whom he has claimed as his "master".[41][33][42] Asked during an interview with Popular Science if the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting affected his thinking or plans in any way, Wilson responded:

... understanding that rights and civil liberties are something that we protect is also understanding that they have consequences that are also protected, or tolerated. The exercise of civil liberties is antithetical to the idea of a completely totalizing state. That's just the way it is.[43]

Wilson is generally opposed to intellectual property rights.[44] He indicated his primary goal is the subversion of state structures and he hopes that his contributions may help to dismantle the existing system of capitalist property relations.[45]

In a January 2013 interview with Glenn Beck about the nature of and motivations behind his effort to develop and share gun 3D printable files Wilson said:

(It's) a real political act, giving you a magazine, telling you that it will never be taken away... That's real politics. That's radical equality. That's what I believe in... I'm just resisting. What am I resisting? I don't know, the collectivization of manufacture? The institutionalization of the human psyche? I'm not sure. But I can tell you one thing: this is a symbol of irreversibility. They can never eradicate the gun from the earth.[46]

Awards

[edit]Wired's "Danger Room" named Wilson one of "The 15 Most Dangerous People in the World" in 2012.[47][48] In 2015 and 2017, Wired said that he was one of the five most dangerous people on the Internet; in 2019 it named him one of the most dangerous people on the internet for the decade.[49][50][51]

Personal life

[edit]Originally from Little Rock, Arkansas, Wilson was student body president at Cabot High School in Cabot, Arkansas and graduated in 2006. He received a bachelor's degree in English from the University of Central Arkansas (UCA) in 2010, where he had a scholarship.[52] While at UCA, Wilson was a member of Sigma Phi Epsilon fraternity and was the president of UCA's student government association. He traveled to China with UCA's study-abroad program.[53]

In 2012, he studied at the University of Texas School of Law but left the university in May 2013 after two years.[26][43][54]

On December 28, 2018, Wilson was indicted by the State of Texas for sexual assault.[55] He was accused paying a 16-year-old girl $500 for sex in a hotel room in Austin, Texas in August 2018, a second-degree felony.[56]

Wilson's defense attorney, F. Andino Reynal, said Wilson believed the girl to be a consenting adult, and that the website where they met required users to declare they are at least 18 years of age before they can create an account.[57] When the police issued a warrant for his arrest, Wilson was in Taipei, Taiwan. He was charged with an immigration violation by the Taiwanese National Immigration Agency (NIA) and deported back to the United States, where his passport was revoked by the U.S. government.[58][59] After he was returned to the U.S. by the United States Marshals Service on September 23, 2018, he was released on $150,000 bond from Harris County Jail in Houston.[60][61]

On August 9, 2019, Wilson accepted a deferred adjudication in exchange for pleading guilty to one charge. He was sentenced to seven years of probation, 475 hours of community service, and fined $1,200.[62][63][64] After completing his probation in 2022, the charges and case were dismissed.[63][65][66]

In a 2024 piece memorializing his time as a producer of The New Radical, venture capitalist Greg Stewart recalled Wilson as "physically imposing," and "solemn to the point of severity." He noted Wilson had in recent years withdrawn from the media spotlight to only become more committed to his cause.[67]

Works

[edit]Bibliography

[edit]- Come and Take It: The Gun Printer's Guide to Thinking Free. New York: Gallery Books (2016). ISBN 978-1476778266.

Filmography

[edit]- As himself

- After Newtown: Guns in America (2013)

- Print the Legend (2014)

- Deep Web (2015)

- No Control (2015)

- The New Radical (2017)

- Death Athletic: A Dissident Architecture[68] (2023)

- As producer

References

[edit]- ^ Kopfstein, Janus (April 12, 2013). "What happens when 3D printing and crypto-anarchy collide?". The Verge. Archived from the original on July 8, 2017. Retrieved May 8, 2013.

- ^ Pangburn, DJ (September 13, 2013). "Whistleblowers and the Crypto-Anarchist Underground: An Interview with Andy Greenberg". Motherboard.tv. Archived from the original on October 6, 2016. Retrieved October 30, 2013.

- ^ Doherty, Brian (December 12, 2012). "What 3-D Printing Means for Gun Rights". Reason. Archived from the original on December 15, 2012. Retrieved December 15, 2012.

- ^ "You don't bring a 3D printer to a gun fight -- yet".

- ^ Morelle, Rebecca (May 6, 2013). "Working gun made with 3D printer". BBC News. Retrieved December 7, 2020.

- ^ Greenberg, Andy (August 23, 2012). "'Wiki Weapon Project' Aims To Create A Gun Anyone Can 3D-Print At Home". Forbes. Archived from the original on January 21, 2013. Retrieved January 14, 2013.

- ^ Hotz, Alexander (November 25, 2012). "3D 'Wiki Weapon' guns could go into testing by end of year, maker claims". The Guardian. Archived from the original on October 30, 2013. Retrieved January 14, 2013.

- ^ a b Beckhusen, Robert (October 1, 2012). "3-D Printer Company Seizes Machine From Desktop Gunsmith". Wired News. Archived from the original on October 3, 2012. Retrieved October 4, 2012.

- ^ Coldewey, Devin (October 2, 2012). "3-D printed gun project derailed by legal woes". NBC News. Archived from the original on October 2, 2012. Retrieved December 15, 2012.

- ^ Farivar, Cyrus (March 17, 2013). "3D-printed gun maker now has federal firearms license to manufacture, deal guns". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on May 3, 2013. Retrieved May 7, 2013.

- ^ a b Rayner, Alex (May 6, 2013). "3D-printable guns are just the start, says Cody Wilson". The Guardian. Archived from the original on July 31, 2013. Retrieved May 6, 2013.

- ^ Brown, Steven Rex (May 13, 2013). "Man who used 3-D printer to create gun hopes efforts can 'destroy the spirit of gun control itself'". Daily News. Archived from the original on May 13, 2013. Retrieved May 21, 2013.

- ^ Andy Greenberg (May 9, 2013). "State Department Demands Takedown Of 3D-Printable Gun Files For Possible Export Control Violations". Forbes. Archived from the original on May 13, 2013. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- ^ Greenberg, Andy (October 1, 2015). "The $1,200 Machine That Lets Anyone Make a Metal Gun at Home". Wired. Archived from the original on August 27, 2015. Retrieved September 2, 2015.

- ^ Greenberg, Andy (June 3, 2015). "I Made an Untraceable AR-15 'Ghost Gun' in My Office – And It Was Easy". Wired. Archived from the original on October 20, 2016. Retrieved March 3, 2020.

- ^ Morales, Miguel. "30 Under 30: The Top Young Lawyers, Policymakers And Power Players". Forbes. Retrieved January 30, 2024.

- ^ Team, Forbes Under 30. "Hall Of Shame: The 10 Most Dubious People Ever To Make Our 30 Under 30 List". Forbes. Retrieved January 30, 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Porter, Jon (November 29, 2023). "Forbes publishes 30 Under 30 "Hall of Shame."". The Verge. Retrieved January 30, 2024.

- ^ "3-D Printed Gun Lawsuit Starts the War Between Arms Control and Free Speech". WIRED. May 6, 2015. Archived from the original on August 28, 2015. Retrieved March 6, 2017.

- ^ Greenberg, Andy (July 10, 2018). "A Landmark Legal Shift Opens Pandora's Box for DIY Guns". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Archived from the original on July 10, 2018. Retrieved July 19, 2018.

- ^ Mattise, Nathan (September 12, 2019). "Judge accepts Cody Wilson plea deal despite "sufficient evidence" of guilt". Ars Technica. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- ^ "Defense Distributed's new era – Cody Wilson resigns, former arts professional steps in". Ars Technica. September 25, 2018. Archived from the original on September 25, 2018. Retrieved September 25, 2018.

- ^ Stephens, Alain (November 20, 2019). "Despite His Criminal Record, Cody Wilson Is Back in the 3D-Printed Gun Business". The Trace. Retrieved March 3, 2020.

- ^ Greenberg, Andy (October 31, 2013). "Dark Wallet Aims To Be The Anarchist's Bitcoin App Of Choice". Forbes. Archived from the original on January 1, 2014. Retrieved December 31, 2013.

- ^ Feuer, Alan (December 14, 2013). "The Bitcoin Ideology". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 15, 2013. Retrieved December 31, 2012.

- ^ a b Del Castillo, Michael (September 24, 2013). "Dark Wallet: A Radical Way to Bitcoin". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on September 25, 2013. Retrieved September 25, 2013.

- ^ "Cody Wilson: Happiness is a 3-D Printed Gun". ReasonTV. April 18, 2014. Archived from the original on May 9, 2014. Retrieved April 19, 2014 – via Youtube.com.

- ^ del Castillo, Michael (November 4, 2014). "Exclusive: Cody Wilson to run for Bitcoin Foundation board, plans its destruction". American City Business Journals. Archived from the original on November 12, 2014. Retrieved November 12, 2014.

- ^ Hicks, William (August 4, 2017). "Meet Hatreon, the new favorite website of the Alt-Right". Newsweek. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- ^ a b c Popescu, Adam (December 4, 2017). "This Crowdfunding Site Runs on Hate". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on December 19, 2017. Retrieved December 18, 2017.

- ^ Hicks, William (August 4, 2017). "Meet Hatreon, The New Favorite Website of the Alt-Right". Newsweek. Archived from the original on October 14, 2017. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- ^ "White supremacists' favorite fundraising site may be imploding". Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- ^ a b "Cody Rutledge Wilson". Southern Poverty Law Center. Archived from the original on March 3, 2019. Retrieved February 17, 2019.

Hatreon processing was suspended by Visa in November.

- ^ Michel, Casey (March 13, 2018). "White supremacists' favorite fundraising site may be imploding". ThinkProgress. Archived from the original on March 3, 2019. Retrieved February 17, 2019.

- ^ a b Steele, Chandra (May 9, 2013). "Dismantle the State: Q&A With 3D Gun Printer Cody Wilson". PC Magazine. Archived from the original on May 10, 2013. Retrieved May 15, 2013.

- ^ Ostroff, Joshua (March 12, 2013). "'Wiki Weapons' Maker Cody Wilson Says 3D Printed Guns 'Are Going To Be Possible Forever'". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on May 20, 2013. Retrieved May 15, 2013.

- ^ Fallenstein, Daniel (December 27, 2012). "All markets become black". Blink. Archived from the original on January 15, 2013. Retrieved January 14, 2013.

- ^ Siegel, Jacob (May 1, 2018). "Send Anarchists, Guns, and Money". The Baffler. Archived from the original on July 30, 2018. Retrieved July 7, 2018.

- ^ Kopfstein, Janus (April 12, 2013). "What happens when 3D printing and crypto-anarchy collide?". The Verge. Archived from the original on July 8, 2017. Retrieved May 8, 2013.

- ^ "A Crypto-Anarchist Will Help You Build a DIY AR-15". Bloomberg. Retrieved April 2, 2022.

- ^ "Cody Wilson Wants to Destroy Your World". Wired. March 11, 2015. Archived from the original on July 8, 2018. Retrieved July 7, 2018.

- ^ Moretti, Eddy (April 9, 2013). "Cody Wilson on 3D Printed Guns". Vice Meets. Season 1. Vice. Archived from the original on July 21, 2018. Retrieved July 7, 2018.

- ^ a b Dillow, Clay (December 21, 2012). "Q+A: Cody Wilson Of The Wiki Weapon Project On The 3-D Printed Future of Firearms". Popular Science. Archived from the original on January 21, 2013. Retrieved January 14, 2013.

- ^ Sackur, Stephen (March 11, 2014). "Cody Wilson". BBC HARDtalk. Season 17. BBC. Archived from the original on October 14, 2018. Retrieved July 7, 2018.

- ^ "Barack Obama Is A Grocery Clerk! A Fraud And A Salesman Used To Sell You Something On TV". BBC. March 12, 2014. Archived from the original on March 18, 2014. Retrieved April 12, 2014.

- ^ Wilson (January 18, 2013). "Wiki Weapons Founder: 'They can never eradicate the gun from the Earth'". Glenn Beck. Archived from the original on January 5, 2019. Retrieved February 17, 2019.

- ^ "30 Influential Pro-Gun Rights Advocates". USACarry.com. May 20, 2013. Archived from the original on November 14, 2013. Retrieved November 22, 2013.

- ^ "The 15 Most Dangerous People in the World". Wired. December 19, 2012. Archived from the original on January 15, 2013. Retrieved January 4, 2013.

- ^ "The Most Dangerous People on the Internet Right Now". Wired. January 1, 2015. Archived from the original on January 9, 2015. Retrieved January 8, 2015.

- ^ "The Most Dangerous People on the Internet in 2017". Wired. December 28, 2017. Archived from the original on July 2, 2018. Retrieved July 2, 2018.

- ^ "The Most Dangerous People on the Internet This Decade". Wired. December 31, 2019. Retrieved March 3, 2020.

- ^ Danny Yadron (January 1, 2014). "Cody Wilson Rattled Lawmakers With Plastic Gun, Now on to Bitcoin Transactions". WSJ. Archived from the original on May 6, 2016. Retrieved March 13, 2017.

- ^ "Document: Cody Wilson: troll, genius, patriot, provocateur, anarchist, attention whore, gun nut or Second Amendment champion?". Cqrcengage.com. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved July 12, 2014.

- ^ Greenberg, Andy. "Waiting for Dark: Inside Two Anarchists' Quest for Untraceable Money". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved July 17, 2022.

- ^ Nathan Mattise (January 3, 2019). "Texas indicts Cody Wilson on multiple counts of sexual assault of a minor". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on September 2, 2019. Retrieved July 6, 2019.

- ^ Hsu, Tiffany (September 19, 2018). "3-D Printed Gun Promoter, Cody Wilson, Is Charged With Sexual Assault of Child". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 17, 2019. Retrieved December 3, 2018.

- ^ Autullo, Ryan (August 9, 2019). "Cody Wilson pleads guilty in child sex case". Austin American-Statesman. Retrieved January 13, 2022.

- ^ Matisse, Nathan (September 21, 2018). "Taiwanese authorities arrest Cody Wilson, intend to deport him". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on September 21, 2018. Retrieved January 18, 2021.

- ^ Lee, Yimou (September 23, 2018). "Texan running 3-D printed guns company sent back to U.S. by Taiwan authorities". Reuters. Archived from the original on January 31, 2019. Retrieved January 18, 2021.

- ^ "3-D printed gun advocate Cody Wilson bonds out of jail in Houston after arrest in Taiwan". Houston Chronicle. September 23, 2018. Archived from the original on September 24, 2018. Retrieved September 24, 2018.

- ^ "3D-printed gun activist Cody Wilson released from Harris County Jail". Fox 26 Houston. Archived from the original on September 24, 2018. Retrieved September 24, 2018.

- ^ Mattise, Nathan (August 9, 2019). "Cody Wilson pleads guilty to lesser charge, will register as sex offender". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on August 12, 2019. Retrieved January 18, 2021.

- ^ a b Mattise, Nathan (September 12, 2019). "Judge accepts Cody Wilson plea deal despite "sufficient evidence" of guilt". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on September 12, 2019. Retrieved January 31, 2021.

- ^ Mattise, Nathan (August 9, 2019). "Cody Wilson pleads guilty to lesser charge, will register as sex offender". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on August 12, 2019. Retrieved January 18, 2021.

- ^ Taylor, Magdalene (September 21, 2023). "Are 3D-Printed Guns Really About Free Speech?". Vice. Retrieved January 21, 2024.

- ^ "Despite His Criminal Record, Cody Wilson Is Back In The 3D-Printed Gun Business". KUT Radio, Austin's NPR Station. November 20, 2019. Retrieved January 24, 2024.

- ^ Stewart, Greg (October 30, 2024). "The Antiheroes We Don't Need". compactmag.com. Compact. Retrieved December 28, 2024.

- ^ Solce, Jessica (October 21, 2023), Death Athletic: A Dissident Architecture (Documentary), Benjamin Denio, John Sullivan, Cody Wilson, Encode Productions, retrieved January 30, 2024

- ^ Dickson, E. J. (May 4, 2020). "'TFW No GF' Is a Deeply Uncomfortable Portrayal of Incel Culture". Rolling Stone.

While acknowledging that Wilson helped secure her access to some of her sources, Moyer [the director] downplays his involvement with the film...

- 1988 births

- Living people

- 21st-century American inventors

- Activists from Little Rock, Arkansas

- Activists from Texas

- American anti-capitalists

- American gun rights activists

- American libertarians

- Crypto-anarchists

- Firearm designers

- People associated with Bitcoin

- People from Austin, Texas

- People from Cabot, Arkansas

- University of Central Arkansas alumni

- University of Texas School of Law alumni