Dariga Nazarbayeva

Dariga Nazarbayeva | |

|---|---|

| Дариға Назарбаева | |

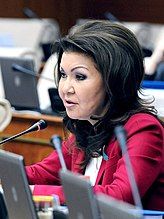

Nazarbayeva in 2019 | |

| 7th Chairwoman of the Senate | |

| In office 20 March 2019 – 2 May 2020 | |

| Deputy | Sergey Gromov Bektas Beknazarov Asqar Şäkirov |

| Preceded by | Kassym-Jomart Tokayev |

| Succeeded by | Mäulen Äşimbaev |

| Deputy Prime Minister of Kazakhstan | |

| In office 11 September 2015 – 13 September 2016 | |

| Prime Minister | Karim Massimov Bakhytzhan Sagintayev |

| Member of the Senate | |

| In office 15 September 2016 – 2 May 2020 | |

| Appointed by | Nursultan Nazarbayev |

| Deputy Chairwoman of the Mäjilis | |

| In office 3 April 2014 – 11 September 2015 | |

| Chairman | Kabibulla Dzhakupov |

| Preceded by | Kabibulla Dzhakupov |

| Succeeded by | Abai Tasbolatov |

| Leader of Amanat in the Mäjilis | |

| In office 3 April 2014 – 11 September 2015 | |

| Leader | Nursultan Nazarbayev |

| Preceded by | Nurlan Nigmatulin |

| Succeeded by | Kabibulla Dzhakupov |

| Member of the Mäjilis | |

| In office 15 January 2021 – 25 February 2022 | |

| In office 15 January 2012 – 11 September 2015 | |

| In office 19 September 2004 – 20 June 2007 | |

| Constituency | Asar List |

| Chairwoman of Asar | |

| In office 25 October 2003 – 4 July 2006 | |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Office abolished |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Dariga Nursultanqyzy Nazarbayeva 7 May 1963 Temirtau, Kazakh SSR, Soviet Union |

| Political party | Amanat (2006−present) |

| Other political affiliations | Asar (2003−2006) |

| Spouse | Rakhat Aliyev (divorced 2007) |

| Children | Nurali (born 1985), Aisultan (1990-2020) and Venera (born 2001)[1] |

| Parent(s) | Nursultan Nazarbayev Sara Alpysqyzy |

| Alma mater | Moscow State University |

Dariga Nursultanqyzy Nazarbayeva (Kazakh: Дариға Нұрсұлтанқызы Назарбаева, Dariğa Nūrsūltanqyzy Nazarbaeva; born 7 May 1963) is a Kazakh businesswoman and politician who is the daughter of Nursultan Nazarbayev who was the President of Kazakhstan from 1990 to 2019. She was a member of the Mäjilis from 2004 to 2007, 2012 to 2015 and 2021 to 2022. She was Deputy Chairwoman of Mäjilis from 2014 to 2015 until being appointed as a Deputy Prime Minister under Massimov's cabinet. She was a member of the Kazakh Senate from 2016 to 2020, serving as Senate Chairwoman from 2019 to 2020. She is one of the richest women in Kazakhstan.[2]

Nazarbayeva began her career in 1994 in media business as she headed Khabar, the largest national television agency in Kazakhstan. In 2003, she founded the Asar party and the following year later in 2004 for the first time, Nazarbayeva was elected to the Mäjilis. While serving the post there, the Asar in 2006 merged with the Amanat, a ruling party that was led by her father Nazarbayev. Following the dissolution of the Mäjilis in 2007, Nazarbayeva did not run for re-election and remained out of politics until her eventual return in 2012 to the Mäjilis seat where she was the deputy chairwoman and parliamentary leader of Amanat. In 2015, Nazarbayeva was appointed by her father as Deputy Prime Minister under PM Karim Massimov before then returning to the Parliament in 2016 as a Senator. After her father's resignation from presidency in 2019, Nazarbayeva took over Kassym-Jomart Tokayev's role as the Senate Chairwoman, while Tokayev in turn, became the President of Kazakhstan. In 2020, she was unexpectedly removed from the post by Tokayev shortly before returning to the Mäjilis once more in 2021.

Because of Nazarbayeva's high-ranking official positions and relations with her father, it had been widely speculated that she was potentially being prepared for presidency as a way to succeed Nazarbayev's legacy in a nepotist fashion despite the dismissed claims by Nazarbayev himself.[3][4]

Early life and education

[edit]Nazarbayeva was born at Temirtau on 7 May 1963. In 1981–1982, she completed her secondary education at K. Satpayev Gymnasium No. 56 in Alma-Ata.[5][6] From 1980 to 1983, she studied at the history department at Moscow State University. She graduated from the S. M. Kirov Kazakh State University in 1985,[7] and in 1991, defending her thesis for a candidate degree in historical sciences at the Moscow State University. In 1998, Nazarbayeva defended her thesis for Ph.D degree in political sciences at the Russian Academy of State Service.[8]

Career

[edit]Nazarbayeva became the vice president of her mother Sara Nazarbayeva's Bobek Children's Charity Fund.[9]

In 1994, Nazarbayeva became the vice president of the Television and Radio of Kazakhstan Republican Corporation. In 1995, the Khabar TV channel was created. The organizations associated to Nazarbayeva purchased the Europa Plus Radio Station, KTK and NTK television companies and popular newspaper Сaravan. TV-Media and Alma-Media companies were established to manage the new media holding.[9] In 1998, Khabar was transformed into a closed joint-stock company, and Nazarbayeva became President of the Company, and in 2001, the Chairperson of the Board of Directors.[9]

Since the late 1990s, Nazarbayeva has regularly appeared on Kazakh TV as a singer. Her repertoire includes Kazakh folk songs, Russian romances, opera arias and songs by Joe Dassin. In 2011, Nazarbayeva gave a recital “Salem, Russia” in Moscow on the new stage in the Bolshoi Theater, and the Organ Hall of Astana.[10] A Russian company Universal Music filmed her concert performances at various venues for the musical television movie My Star. The two-part film was presented in 2012.[11][12] In 2013, she gave a concert, co-organized by Count Pierre Sheremetev, at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées in Paris, with the Orchestre Lamoureux directed by Dmitry Yablonsky and the Sazgen sazi group directed by Baghdat Tilegenov, and with some artists as the pianist Timur Urmancheev,[13] Sundet Baigozhin or Medet Chotabaev.

Political career

[edit]Chair of the Asar (2003–2006)

[edit]In October 2002, Nazarbayeva became the Chairperson of the Board of Trustees of the Choice of the Young People block; it was proposed to create the Congress of Youth of Kazakhstan at the first conference of the block.[14]

In October 2003, Nazarbayeva organized and became the leader of the Asar Republican Party.[15][16][17] In a few months, more than 167,000 applications were collected from those wishing to join Asar; 139,000 applications were processed and authenticated, and 77,000 signatures were submitted to the Ministry of Justice for registration.[18] In December 2003, the party was registered.[19]

According to the results of the elections to the Mäjilis in 2004, the party polled 541,239 (11.38%) votes on a party list basis and ranked the third; Nazarbayeva became an elected member from the Asar party-list in the Mäjilis, along with three deputies from the party who were elected in single-member constituencies.

On 4 July 2006, an extraordinary party convention was held where they decided to merge with the Otan Republican Political Party (later Nur Otan from December 2006), with Nazarbayeva being elected as the deputy chairwoman of Amanat under her father's chairmanship.[20][21]

Parliamentarian career

[edit]Member of the Mäjilis (2004–2007, 2012–2015, 2021–present)

[edit]

In February 2005, a new Deputy Group of Aimak formed in the Parliament, consisting of 36 deputies (28 deputies from the Mäjilis and 8 deputies from the Senate). Nazarbayeva was elected as the group leader. The main goals of the Aimak Deputy Group were to promote and monitor the implementation of existing state and industry programs aimed at regional development, take an active part in the development and legislative support of administrative reform and local self-government and develop entrepreneurship.[22] She remained as a member of the Mäjilis until its dissolution on 20 June 2007.[23]

In the 2012 Kazakh legislative election, Nazarbayeva ran again in the Amanat party list which won 83 seats.[24] She headed the Mäjilis Committee on Socio-Cultural Development.[25]

On 3 April 2014, Nazarbayeva was unanimously chosen as a Mäjilis deputy chairwoman and the parliamentary leader of Amanat.[26] On 11 September 2015, she was appointed as a Deputy Prime Minister.[27][28]

Nazarbayeva reappeared on the Amanat party-list at a congress on 25 November 2020 where she made her first public appearance since being dismissed from the Senate Chairwoman post, bringing her candidacy to the Mäjilis seat again.[29] The Amanat maintained its control over the Mäjilis following the 2021 legislative elections, sweeping 76 seats.[30] From there, she became a member of the Committee for Economic Reforms and Regional Development.[31]

Member of the Senate (2016–2020)

[edit]

On 13 September 2016, Nazarbayeva was appointed to the Senate; she was designated as the head of the Senate's International Affairs, Defense, and Security Committee on 16 September.[32]

Chairwoman of the Senate

[edit]On the same day her father stepped down as the President of Kazakhstan, Nazarbayeva was appointed as the Senate Chair in a unanimous secret ballot on 20 March 2019.[33] She succeeded Kassym-Jomart Tokayev in that role, who became the acting president of the country.[33] According to The New York Times, this may have been a signal that Nazarbayeva was being groomed to become president herself.[34] Several speculations arose that Nazarbayeva was preparing her presidential bid for the 2019 presidential elections in which the allegations were revealed to be false according to her close aide on 9 April 2019.[35]

On 2 May 2020, she was removed from the Senate and her role as the Chair by Tokayev.[36] Many theories arose that either Tokayev was expanding his political influence or a sign of growing feud between the Kazakhstan's ruling elite.[37] Others claimed that the reason was due to public scandals regarding her son Aisultan and the British court case which ruined Nazarbayeva's reputation and her fathers image.[38][39]

Awards and decorations

[edit] Kazakhstan:

Kazakhstan:

Order of the Leopard, 1st class (2 December 2021)[40]

Order of the Leopard, 1st class (2 December 2021)[40] Order of the Leopard, 2nd class (December 2013)[41]

Order of the Leopard, 2nd class (December 2013)[41] Order of Parasat (December 2004)[42]

Order of Parasat (December 2004)[42] Astana Medal (17 August 1998)

Astana Medal (17 August 1998) Medal "10 Years of Independence of the Republic of Kazakhstan" (2001)[43]

Medal "10 Years of Independence of the Republic of Kazakhstan" (2001)[43] Medal "10 Years of the Parliament of the Republic of Kazakhstan" (7 November 2005)

Medal "10 Years of the Parliament of the Republic of Kazakhstan" (7 November 2005) Medal "10 Years of Astana" (6 May 2008)

Medal "10 Years of Astana" (6 May 2008) Medal "20 Years of Independence of the Republic of Kazakhstan" (2011)

Medal "20 Years of Independence of the Republic of Kazakhstan" (2011) Medal "20 Years of Tenge" (September 2013)

Medal "20 Years of Tenge" (September 2013) Medal "20 Years of the Constitution of the Republic of Kazakhstan" (5 August 2015)

Medal "20 Years of the Constitution of the Republic of Kazakhstan" (5 August 2015) Medal of Nur Otan (3 May 2013)

Medal of Nur Otan (3 May 2013) Medal of the Constitutional Council of the Republic of Kazakhstan (30 August 2013)

Medal of the Constitutional Council of the Republic of Kazakhstan (30 August 2013) Medal "20th Anniversary of the Assembly of the People of Kazakhstan" (14 March 2015)

Medal "20th Anniversary of the Assembly of the People of Kazakhstan" (14 March 2015) Medal "25 Years of Independence of the Republic of Kazakhstan" (2016)

Medal "25 Years of Independence of the Republic of Kazakhstan" (2016) Medal "20 Years of Astana" (30 June 2018)

Medal "20 Years of Astana" (30 June 2018)

CIS:

CIS:

Order of the Commonwealth (2017)[44]

Order of the Commonwealth (2017)[44] Silver medal of the Inter-Parliamentary Assembly of the Commonwealth of Independent States, 20 years (27 March 2012)

Silver medal of the Inter-Parliamentary Assembly of the Commonwealth of Independent States, 20 years (27 March 2012) Medal of the Inter-Parliamentary Assembly of the Commonwealth of Independent States, 25 years (27 March 2017)

Medal of the Inter-Parliamentary Assembly of the Commonwealth of Independent States, 25 years (27 March 2017)

France:

France:

Chevalier of the National Ordre des Arts et des Lettres (April 2009)[45]

Chevalier of the National Ordre des Arts et des Lettres (April 2009)[45]

Personal life

[edit]Family

[edit]

Nazarbayeva had a long marriage to Kazakh businessman and politician Rakhat Aliyev until their divorce in June 2007. Aliyev held senior posts in Kazakhstan's domestic intelligence agency and foreign ministry, and later as ambassador to Austria.[34] In 2004, a woman alleged to be Aliyev's mistress was found dead, having fallen from a tall apartment building in Beirut.[34] He was stripped of his titles in 2007 after critiquing President Nazarbayev for altering the nation's constitution to allow him to be president for life.[34] Aliyev claimed that his divorce was executed without his consent, and that it was forced by Nazarbayev.[46]

Aliyev was convicted in absentia for various crimes in Kazakhstan. Austria refused to extradite him, but were preparing to try him for the kidnapping and murder of two Kazakh bank officials.[34] Before the trial, he was found dead in his Austrian jail cell due to alleged suicide.[34]

Nazarbayeva has two sons with Aliyev, Nurali and Aisultan, and a daughter Venera.[47] She is also a grandmother. Nurali's wife gave birth to Laura Aliyeva in 2013.[48]

On 23 January 2020, Nazarbayeva's son, Aisultan, made a public statement on his Facebook page, claiming that his grandfather Nazarbayev was allegedly his dad and that his mother Nazarbayeva has been attempting to kill him while living in London.[49] Nazarbayeva made no responses regarding the case made by her son. The next day on 24 January, a female correspondent from the RFE/RL attempted to receive response from Nazarbayeva regarding her son's claims as she was walking by in the Parliament building hallway where one of Nazarbayeva's security guards ended up grabbing the reporter by the arm and covering her mouth.[50] On 16 August 2020, Aisultan was found dead in London with the cause of his death being allegedly due to cardiac arrest.[51] In response to the incident, Nazarbayeva stated that "my family is devastated at the loss of our beloved Aisultan and we ask for privacy at this very difficult time."[52]

Offshore activities

[edit]

In 2018, it was revealed by the Panama Papers that Nazarbayeva was the sole shareholder of an off-shore sugar company based in the British Virgin Islands which did business in Kazakhstan. Her son, Nurali, was also named in the papers as being a client of Mossack Fonseca in Panama, and having two companies and luxury yacht also registered in the British Virgin Islands.[53][54] According to Newsweek, "this is a sharp contradiction from Nazarbayev's frequent appeals to entrepreneurs in the oil-rich country to pay taxes in Kazakhstan."[54] The Panama Papers also suggest she may be the owner, through an off-shore company, of 221B Baker Street, the $183 million property famous as being the fictional address of Sherlock Holmes.[55]

On 10 March 2020, a British court announced the names of the owners of properties worth $100 million, which were issued an UWO in the spring of 2019. The owners turned out to be Nazarbayeva and her eldest son, Nurali Aliyev, with his wife Aida. The representative of the defendants at the hearing explained that the owners can confirm the source of the funds, since at that time they were engaged in business.[56] In April, the High Court of Justice declared the claims by the British law enforcement agencies unfounded and as a result, the case was overturned.[57]

Wealth

[edit]According to Forbes Magazine in 2013 her wealth was about $595 million. It was through her involvement in the companies such as Europe Plus Kazakhstan JSC, NTK, AlmaInvestHolding, Almatystroysnab LLP, and ALMA TV.[58] She also founded Kazakhstan's main TV network, Khabar Agency.[59]

References

[edit]- ^ "Алиев Рахат Мухтарович (персональная справка)" (in Russian). Zakon.kz. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- ^ "Как Дарига Назарбаева пережила опалу и смерть мужа и чуть было не стала преемницей отца". Forbes.ru (in Russian). 9 April 2019. Retrieved 6 December 2023.

- ^ "Kazakh President Nazarbayev Says Power Won't Be Family Business". Bloomberg.com. 23 November 2016. Retrieved 26 March 2021.

- ^ Moscow, Tom Parfitt. "Dariga Nazarbayeva, daughter of Kazakh strongman, positioned for dynastic takeover". The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- ^ Святослав Антонов (3 September 2015). "Легендарные школы Алматы". Vox Populi (in Russian). Retrieved 23 April 2020.

- ^ "Дарига Назарбаева стала спикером Сената Парламента Казахстана" (in Russian). 20 March 2019. Archived from the original on 19 July 2020. Retrieved 23 April 2020.

- ^ "Биография Дариги Назарбаевой". РИА Новости (in Russian). 20 March 2019. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- ^ "Назарбаева Дарига Нурсултановна (персональная справка)" (in Russian). Retrieved 23 April 2020.

- ^ a b c "Дарига Назарбаева: с чего начиналась карьера самой влиятельной женщины в Казахстане" (in Russian). Central Asia Monitor. 2 October 2015. Retrieved 23 April 2020.

- ^ "Дарига Назарбаева даст сольные концерты в Москве и Астане". Zakon.kz. 29 November 2011. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- ^ Darimbet, Nazira (16 February 2012). "Дарига Назарбаева снялась в кино". Радио Азаттык. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- ^ "В Алматы презентован музыкальный фильм с участием Дариги Назарбаевой". KTK. 17 February 2012. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- ^ 88 notes pour piano solo, Jean-Pierre Thiollet, Neva Ed., 2015, p. 192. ISBN 978 2 3505 5192 0

- ^ "Дарига Назарбаева - попечитель молодёжи" (in Russian). Retrieved 23 April 2020.

- ^ "Дарига Назарбаева агитирует молодежь вступать в общественное объединение "Асар"" (in Russian). 11 September 2003. Retrieved 23 April 2020.

- ^ "О том, что молодежи необходимо активнее участвовать в общественной жизни страны и в частности в выборах, говорила в Евразийском университете в Астане Дарига Назарбаева" (in Russian). 13 September 2003. Retrieved 23 April 2020.

- ^ "Настает тот самый момент…" (in Russian). 19 September 2003. Retrieved 23 April 2020.

- ^ "Председатель партии "Асар" впервые после официальной регистрации партии встретилась с журналистами" (in Russian). 22 December 2003. Retrieved 23 April 2020.

- ^ "Зарегистрирована республиканская политическая партия "Асар"" (in Russian). 19 December 2003. Retrieved 23 April 2020.

- ^ "Партия "Асар" приняла решение о слиянии с партией "Отан"" (in Russian). 4 July 2006. Retrieved 23 April 2020.

- ^ "Победа партии "Нур Отан" окончательно закрепила в Казахстане авторитарный режим" (in Russian). Archived from the original on 24 July 2016. Retrieved 23 April 2020.

- ^ "В парламенте образована новая депутатская группа "Аймак"" (in Russian). Караван. 17 February 2005. Retrieved 23 April 2020.

- ^ Pannier, Bruce (20 June 2007). "Kazakh President Dissolves Parliament". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- ^ "TABLE-Kazakh parliamentary election final results". Reuters. 17 January 2012. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- ^ "Мажилис избрал главой комитета по социально-культурному развитию Даригу Назарбаеву; по финансам и бюджету". Zonakz.net. 20 January 2012. Retrieved 29 April 2020.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Gizitdinov, Nariman (3 April 2014). "Kazakh President's Daughter Promoted to Top Position in Comeback". www.bloomberg.com. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- ^ "Dariga Nazarbayeva appointed Vice PM of Kazakhstan". Kazinform. 11 September 2015. Archived from the original on 28 April 2018. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- ^ Kazakhstani President appoints Dariga Nazarbayeva as deputy PM, Ilaha Ahmadova in Astana for Azertac news agency, Baku 12 September 2015.Retrieved: 12 September 2015.

- ^ Presse, AFP-Agence France (25 November 2020). "Ex-Kazakh President's Daughter Returns To Politics With Parliament Run". www.barrons.com. Archived from the original on 21 January 2021. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- ^ Putz, Catherine (14 January 2021). "Dariga Nazarbayeva Headed Back to Parliament". thediplomat.com. Archived from the original on 13 January 2021. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- ^ "Дарига Назарбаева вошла в Комитет по экономическим реформам Мажилиса". Tengrinews.kz (in Russian). 15 January 2021. Archived from the original on 15 January 2021. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- ^ "Kazakh president's daughter appointed head Of Senate committee", Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, 16 September 2016.

- ^ a b Astrasheuskaya, Nastassia (20 March 2019). "Nazarbayev's daughter becomes Kazakh heir apparent". Financial Times. Retrieved 20 March 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f MacFarquhar, Neil (20 March 2019). "Rise of First Daughter in Kazakhstan Fuels Talk of Succession". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 20 March 2019.

- ^ tengrinews.kz (9 April 2019). "Будет ли Дарига Назарбаева участвовать в выборах президента". Tengrinews.kz (in Russian). Archived from the original on 10 April 2019. Retrieved 26 March 2021.

- ^ "Daughter of former Kazakh leader leaves key Senate post". Reuters. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- ^ Welle (www.dw.com), Deutsche. "Президент Казахстана снял дочь Назарбаева с поста спикера сената | DW | 02.05.2020". DW.COM (in Russian). Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- ^ Putz, Catherine (5 May 2020). "Dariga Nazarbayeva Dismissed From Top Senate Seat". thediplomat.com. Archived from the original on 6 May 2020. Retrieved 26 March 2021.

- ^ "A Kazakh politician with a pedigree unexpectedly loses her job". The Economist. 7 May 2020. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 26 March 2021.

- ^ "Нуртай Абыкаев, Дарига Назарбаева, Куаныш Султанов награждены орденом «Барыс» І степени". inform.kz. 13 December 2021. Retrieved 18 June 2022.

- ^ "Даригу Назарбаеву наградили орденом «Барыс» II степени". news.mail.ru. Archived from the original on 1 April 2018. Retrieved 18 June 2022.

- ^ "Дочки-орденочки. Даригу Назарбаеву удостоили "Парасата"". centrasia.ru. Archived from the original on 1 April 2018. Retrieved 18 June 2022.

- ^ "Ирония судьбы или…C юбилеем!". centrasia.ru. Archived from the original on 2 December 2008. Retrieved 18 June 2022.

- ^ "Дарига Назарбаева получила орден ко Дню Независимости". baigenews.kz. 15 December 2017. Retrieved 18 June 2022.

- ^ "Дарига Назарбаева награждена французским Орденом искусств и литературы". nomad.su. 10 April 2009. Retrieved 18 June 2022.

- ^ Nazarbayev's Son-in-Law Is Divorced Archived 2 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine Moscow Times, June 13, 2007

- ^ Моя семья Archived 2007-03-05 at the Wayback Machine СЕМЬЯ

- ^ У старшего сына Дариги Назарбаевой Нурали родилась дочь Лаура epraha

- ^ "Внук Назарбаева заявил, что он — не внук, а сын". EADaily. 23 January 2020. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ Азаттык, Радио (14 February 2020). ""Грязная игра". Новые заявления Айсултана Назарбаева и реакция властей". Радио Азаттык. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ "Grandson of Kazakhstan's first president Nazarbayev died in London". TASS. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- ^ "Дарига Назарбаева высказалась о смерти Айсултана". Liter.kz (in Russian). 16 August 2020. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- ^ "Kazakhstan: Presidential daughter getting Panama-ed at a tricky time". Eurasianet. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- ^ a b EDT, Damien Sharkov On 4/25/16 at 7:56 AM (25 April 2016). "Kazakhstan won't investigate #PanamaPaper links to the president's family". Newsweek. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Haldevang, Max de (5 April 2018). "The unsolved mystery of who owns Sherlock Holmes's original £130 million home". Quartz. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- ^ "Unexplained Wealth Order focuses on London mansion". BBC. 10 March 2010. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- ^ Milligan, Ellen (8 April 2020). "Family Wins Fight With U.K. Cops Over 'Billionaire Row' Home". Bloomberg. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- ^ "Дарига Назарбаева — Forbes Казахстан". www.forbes.kz/. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- ^ "Widowed opera singer daughter of 'Papa' - Kazakhstan's next president?". Reuters. 20 March 2019. Archived from the original on 21 March 2019. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- 1964 births

- Living people

- Asar (party) politicians

- Chairmen of the Senate of Kazakhstan

- 21st-century Kazakhstani women politicians

- 21st-century Kazakhstani politicians

- Members of the Mäjilis

- Children of presidents

- People from Temirtau

- Nursultan Nazarbayev family

- Recipients of the Order of Parasat

- Chevaliers of the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres

- Deputy prime ministers of Kazakhstan