Spike Lee

Spike Lee | |

|---|---|

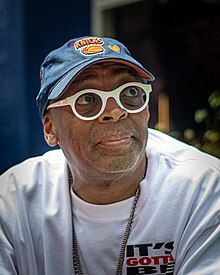

Lee in June 2024 | |

| Born | Shelton Jackson Lee March 20, 1957 |

| Education | Morehouse College (BA) New York University (MFA) |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1977–present |

| Works | Filmography |

| Board member of | 40 Acres and a Mule Filmworks |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 2 |

| Parent | Bill Lee |

| Relatives |

|

| Awards | Full list |

Shelton Jackson "Spike" Lee (born March 20, 1957) is an American film director, producer, screenwriter, actor, and author. His work has continually explored race relations, issues within the black community, the role of media in contemporary life, urban crime and poverty, and other political issues. Lee has won numerous accolades for his work, including an Academy Award, two Primetime Emmy Awards, a BAFTA Award, and two Peabody Awards. He has also been honored with an Honorary BAFTA Award in 2002, an Honorary César in 2003, and the Academy Honorary Award in 2015.

His production company, 40 Acres and a Mule Filmworks, has produced more than 35 films since 1983. He made his directorial debut with She's Gotta Have It (1986). He has since written and directed such films as School Daze (1988), Do the Right Thing (1989), Mo' Better Blues (1990), Jungle Fever (1991), Malcolm X (1992), Crooklyn (1994), Clockers (1995), 25th Hour (2002), Inside Man (2006), Chi-Raq (2015), BlacKkKlansman (2018), and Da 5 Bloods (2020). Lee also acted in eleven of his feature films. He is also known for directing numerous documentary projects including the 4 Little Girls (1997), the HBO series When the Levees Broke (2006), the concert film American Utopia (2020), and NYC Epicenters 9/11→2021½ (2021).

His films have featured breakthrough performances from actors such as Denzel Washington, Laurence Fishburne, Samuel L. Jackson, Giancarlo Esposito, Rosie Perez, Delroy Lindo, and John David Washington. Lee's films Do the Right Thing, Bamboozled, Malcolm X, 4 Little Girls, and She's Gotta Have It were each selected by the Library of Congress for preservation in the National Film Registry for being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[1][2][3] He has received a Gala Tribute from the Film Society of Lincoln Center as well as the Dorothy and Lillian Gish Prize.[4][5]

Early life and education

Shelton Jackson Lee was born in Atlanta, Georgia, the son of Jacqueline Carroll (née Shelton), a teacher of arts and black literature, and William James Edward Lee III, a jazz musician and composer.[6][7] Lee has five younger siblings, three of whom (Joie, David, and Cinqué) have worked in many different positions in Lee's films; a fourth, Christopher, died in 2014.[8] His youngest sibling is half-brother Arnold. Director Malcolm D. Lee is his cousin. When he was a child, the family moved from Atlanta to Brooklyn, New York. His mother nicknamed him "Spike" during his childhood. He attended John Dewey High School in Brooklyn's Gravesend neighborhood.

Lee enrolled in Morehouse College, a historically black college in Atlanta, where he made his first student film, Last Hustle in Brooklyn. He took film courses at Clark Atlanta University and graduated with a B.A. in mass communication from Morehouse. He did graduate work at New York University's Tisch School of the Arts, where he earned a Master of Fine Arts in film and television.[9]

Career

1980s

In 1983, Lee premiered his first independent short film titled, Joe's Bed-Stuy Barbershop: We Cut Heads. Lee submitted the film as his master's degree thesis at the Tisch School of the Arts.[10] Lee's classmates Ang Lee and Ernest R. Dickerson worked on the film as assistant director and cinematographer, respectively. The film was the first student film to be showcased in Lincoln Center's New Directors New Films Festival. Lee's father, Bill Lee, composed the score. The film won a Student Academy Award.

In 1985, Lee began work on his first feature film, She's Gotta Have It. The black-and-white film concerns a young woman (played by Tracy Camilla Johns) who is seeing three men, and the feelings this arrangement provokes. The film was Lee's first feature-length film, and launched Lee's career. Lee wrote, directed, produced, starred and edited the film with a budget of $175,000, he shot the film in two weeks. When the film was released in 1986, it grossed over $7 million at the U.S. box office.[11] New York Times film critic A.O. Scott wrote that the film "ushered in (along with Jim Jarmusch's Stranger Than Paradise) the American independent film movement of the 1980s. It was also a groundbreaking film for African-American filmmakers and a welcome change in the representation of blacks in American cinema, depicting men and women of color not as pimps and whores, but as intelligent, upscale urbanites."[12]

In 1989, Lee made perhaps his most seminal film, Do the Right Thing, which focused on a Brooklyn neighborhood's simmering racial tension on a hot summer day. The film's cast included Lee, Danny Aiello, Bill Nunn, Ossie Davis, Ruby Dee, Giancarlo Esposito, Rosie Perez, John Turturro, Martin Lawrence and Samuel L. Jackson. The film gained critical acclaim as one of the best films of the year from film critics including both Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert who ranked the film as the best of 1989, and later in their top 10 films of the decade (No. 6 for Siskel and No. 4 for Ebert).[13] Ebert later added the film to his list of The Great Movies.[14]

To many people's surprise, the film was not nominated for Best Picture or Best Director at the Academy Awards. The film only earned two Academy Award nominations for Best Original Screenplay, Spike Lee's first Oscar nomination, and for Best Supporting Actor for Danny Aiello. At the Academy ceremony Kim Basinger, who was a presenter that evening, stated that Do the Right Thing also deserved a Best Picture nomination stating, "We've got five great films here, and they are great for one reason, because they tell the truth, but there is one film missing from this list because ironically it might tell the biggest truth of all and that's Do the Right Thing".[15] The film that did win Best Picture was Driving Miss Daisy, a film that focused on race relations between an elderly Jewish woman (Jessica Tandy) and her driver (Morgan Freeman).[16] Lee said in an April 7, 2006, interview with New York magazine that the other film's success, which he thought was based on safe stereotypes, hurt him more than if his film had not been nominated for an award.[17]

1990s

After the 1990 release of Mo' Better Blues, Lee was accused of antisemitism by the Anti-Defamation League and several film critics. They criticized the characters of the club owners Josh and Moe Flatbush, described as "Shylocks". Lee denied the charge, explaining that he wrote those characters in order to depict how black artists struggled against exploitation. Lee said that Lew Wasserman, Sidney Sheinberg, or Tom Pollock, the Jewish heads of MCA and Universal Studios, were unlikely to allow antisemitic content in a film they produced. He said he could not make an antisemitic film because Jews run Hollywood, and "that's a fact".[18]

In 1992, Spike released his biographical epic film Malcolm X based on the Autobiography of Malcolm X, starring Denzel Washington as the famed civil rights leader. The film dramatizes key events in Malcolm X's life: his criminal career, his incarceration, his conversion to Islam, his ministry as a member of the Nation of Islam and his later falling out with the organization, his marriage to Betty X, his pilgrimage to Mecca and reevaluation of his views concerning whites, and his assassination on February 21, 1965. Defining childhood incidents, including his father's death, his mother's mental illness, and his experiences with racism are dramatized in flashbacks. The film received widespread critical acclaim including from critic Roger Ebert ranked the film No. 1 on his Top 10 list for 1992 and described the film as "one of the great screen biographies, celebrating the sweep of an American life that bottomed out in prison before its hero reinvented himself."[19] Ebert and Martin Scorsese, who was sitting in for late At the Movies co-host Gene Siskel, both ranked Malcolm X among the ten best films of the 1990s.[20] Denzel Washington's portrayal of Malcolm X in particular was widely praised and he was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actor. Washington lost to Al Pacino (Scent of a Woman), a decision which Lee criticized, saying "I'm not the only one who thinks Denzel was robbed on that one."[21]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

His 1997 documentary 4 Little Girls, about the girls killed in the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1963, was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Feature Documentary.[22] In 2017, the film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[23]

2000s

In 2002, Lee directed 25th Hour starring Edward Norton, and Philip Seymour Hoffman which opened to positive reviews, with several critics since having named it one of the best films of its decade. Film critic Roger Ebert added the film to his "Great Movies" list on December 16, 2009.[24] A. O. Scott,[25] Richard Roeper[26] and Roger Ebert all put it on their "best films of the decade" lists.[27] It was later named the 26th greatest film since 2000 in a BBC poll of 177 critics.[28] The film was also a financial success earning almost $24 million against a $5 million budget.[29]

In 2006, Lee directed Inside Man starring Denzel Washington, Jodie Foster, and Clive Owen, Chiwetel Ejiofor, Willem Dafoe and Christopher Plummer. The film was an unusual film for Lee considering it was a studio heist thriller. The film was a critical and financial success earning $186 million off a $45 million budget. Empire gave the film four stars out of five, concluding, "It's certainly a Spike Lee film, but no Spike Lee Joint. Still, he's delivered a pacy, vigorous and frequently masterful take on a well-worn genre. Thanks to some slick lens work and a cast on cracking form, Lee proves (perhaps above all to himself?) that playing it straight is not always a bad thing."[30]

On May 2, 2007, the 50th San Francisco International Film Festival honored Spike Lee with the San Francisco Film Society's Directing Award. In 2008, he received the Wexner Prize.[31] In 2013, he won The Dorothy and Lillian Gish Prize, one of the richest prizes in the American arts worth $300,000.[32]

2010s

In 2015, Lee received an Academy Honorary Award from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences for his contributions to film.[33] Friends and frequent collaborators Wesley Snipes, Denzel Washington, Samuel L. Jackson presented Lee with the award at the private Governors Awards ceremony.[34]

Lee directed, wrote, and produced the MyCareer story mode in the video game NBA 2K16.[35] Later that same year, after a perceived long dip in quality, Lee rebounded with a musical drama film, Chi-Raq. The film is a modern-day adaptation of the ancient Greek play "Lysistrata" by Aristophanes set in modern-day Chicago's Southside and explores the challenges of race, sex, and violence in America. Teyonah Parris, Angela Bassett, Jennifer Hudson, Nick Cannon, Dave Chappelle, Wesley Snipes, John Cusack, and Samuel L. Jackson starred in the film. The film was released by Amazon Studios in select cities in November. Chi-Raq received generally positive reviews from critics. On Rotten Tomatoes, the film has rating of 82% with the site's critical consensus stating, "Chi-Raq is as urgently topical and satisfyingly ambitious as it is wildly uneven – and it contains some of Spike Lee's smartest, sharpest, and all-around entertaining late-period work."[36]

Lee's 2018 film BlacKkKlansman, a true crime drama set in the 1970s centered around the true story of a black police officer, Ron Stallworth infiltrating the Ku Klux Klan. The film premiered at the 2018 Cannes Film Festival, where it won the Grand Prix and opened the following August.[37] The film received near universal praise when it opened in North America receiving a 96% on Rotten Tomatoes with the critics consensus reading, "BlacKkKlansman uses history to offer bitingly trenchant commentary on current events – and brings out some of Spike Lee's hardest-hitting work in decades along the way."[38] In 2019, during the awards season leading up to the Academy Awards, Lee was invited to join a Directors Roundtable conversation run by The Hollywood Reporter. The roundtable included Ryan Coogler (Black Panther), Yorgos Lanthimos (The Favourite), Alfonso Cuarón (Roma), Marielle Heller (Can You Ever Forgive Me?), and Bradley Cooper (A Star is Born).[39] It was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Picture and Best Director (Lee's first ever nomination in this category). Lee won his first competitive Academy Award in the category Best Adapted Screenplay.[40][41] When asked by journalists from the BBC if the Best Picture winner Green Book offended him, Lee replied, "Let me give you a British answer, it's not my cup of tea".[42] Many journalists in the industry noted how the 2019 Oscars with BlacKkKlansman competing against eventual winner Green Book mirrored the 1989 Oscars with Lee's film Do the Right Thing missing out on a Best Picture nomination over the eventual winner Driving Miss Daisy.[43][44][45]

2020s

Lee's Vietnam war film Da 5 Bloods was released on Netflix. The film starred Delroy Lindo, Jonathan Majors, Clarke Peters, Isiah Whitlock Jr., Mélanie Thierry, Paul Walter Hauser and Chadwick Boseman.[46] The film was released worldwide on June 12, 2020.[47][48] The film's plot follows a group of aging Vietnam War veterans who return to the country in search of the remains of their fallen squad leader, as well as the treasure they buried while serving there. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the film was scheduled to premiere out-of-competition at the 2020 Cannes Film Festival, then play in theaters in May or June before streaming on Netflix.[49] The film received widespread critical acclaim; the website Rotten Tomatoes gave it an approval rating of 92% based on 252 reviews, with the critical consensus reading: "Fierce energy and ambition course through Da 5 Bloods, coming together to fuel one of Spike Lee's most urgent and impactful films."[50] On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 82 out of 100, based on 49 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[51][52]

Lee's next project will be a movie musical about the origin story of Viagra, Pfizer's erectile dysfunction drug.[53] He has signed a deal with Netflix to direct and produce more movies.[54] In February 2024, it was announced that Spike Lee was confirmed as the director of the remake of High and Low (1963), directed by Akira Kurosawa with Denzel Washington to star.[55]

Academic career and teaching

In 1991, Lee taught a course at Harvard about filmmaking. In 1993, he began to teach at New York University's Tisch School of the Arts in the Graduate Film Program. It was there that he received his master of fine arts. In 2002, he was appointed as artistic director of the school.[56] He is now a tenured professor at NYU.[57]

Commercials

In mid-1990, Levi's hired Lee to direct a series of TV commercials for their 501 button-fly jeans.[58] Marketing executives from Nike[59] offered Lee a job directing commercials for the company. They wanted to pair Lee's character, Mars Blackmon, who greatly admired athlete Michael Jordan, and Jordan in a marketing campaign for the Air Jordan line. Later, Lee was asked to comment on the phenomenon of violence related to inner-city youths trying to steal Air Jordans from other kids.[60] He said that, rather than blaming manufacturers of apparel that gained popularity, "deal with the conditions that make a kid put so much importance on a pair of sneakers, a jacket and gold".[60] Through the marketing wing of 40 Acres and a Mule, Lee has directed commercials for Converse,[61] Jaguar,[62] Taco Bell,[63] and Ben & Jerry's.[64]

Artistic style and themes

Lee's films are typically referred to as "Spike Lee Joints". The closing credits always end with the phrases "By Any Means Necessary", "Ya Dig", and "Sho Nuff".[65] His 2013 film, Oldboy, used the traditional "A Spike Lee Film" credit after producers had it re-edited.[66]

Themes

Lee's films have examined race relations,[67] colorism in the black community, the role of media in contemporary life,[68] urban crime and poverty, and other political issues. His films are also noted for their unique stylistic elements, including the use of dolly shots to portray the characters "floating" through their surroundings, which he has had his cinematographers repeatedly use in his work.[69]

Influences

In 2018, during an interview with GQ, Lee cited some of his favorite films as Elia Kazan's On the Waterfront (1954) and A Face in the Crowd (1957), as well as Martin Scorsese's Mean Streets (1973). Lee says that he befriended Scorsese after attending a screening of After Hours at NYU.[70]

Filmography

| Year | Title | Distributor |

|---|---|---|

| 1986 | She's Gotta Have It | Island Pictures |

| 1988 | School Daze | Columbia Pictures |

| 1989 | Do the Right Thing | Universal Pictures |

| 1990 | Mo' Better Blues | |

| 1991 | Jungle Fever | |

| 1992 | Malcolm X | Warner Bros. |

| 1994 | Crooklyn | Universal Pictures |

| 1995 | Clockers | |

| 1996 | Girl 6 | 20th Century Fox |

| Get on the Bus | Columbia Pictures | |

| 1998 | He Got Game | Touchstone Pictures |

| 1999 | Summer of Sam | |

| 2000 | Bamboozled | New Line Cinema |

| 2002 | 25th Hour | Touchstone Pictures |

| 2004 | She Hate Me | Sony Pictures Classics |

| 2006 | Inside Man | Universal Pictures |

| 2008 | Miracle at St. Anna | Touchstone Pictures |

| 2012 | Red Hook Summer | Variance Films |

| 2013 | Oldboy | FilmDistrict |

| 2014 | Da Sweet Blood of Jesus | Gravitas Ventures |

| 2015 | Chi-Raq | Roadside Attractions |

| 2018 | Pass Over | Amazon Studios |

| BlacKkKlansman | Focus Features | |

| 2020 | Da 5 Bloods | Netflix |

| TBA | Highest 2 Lowest | A24 Apple TV |

Awards and honors

In 1983, Lee won the Student Academy Award for his film Joe's Bed-Stuy Barbershop: We Cut Heads.[71] He won awards at the Black Reel Awards for Love and Basketball,[72] the Black Movie Awards for Inside Man, and the Berlin International Film Festival for Get on the Bus.[73] He won BAFTA Award for Best Adapted Screenplay for BlacKkKlansman.[74]

Lee was nominated for Academy Awards for Best Original Screenplay for Do the Right Thing[75][76] and Best Documentary for 4 Little Girls, but did not win either award. In November 2015, he was given the Academy Honorary Award for his contributions to filmmaking.[77] In 2019, he received his first Best Picture and Best Director nominations.[78]

In 2015, at the age of 58, Lee became the youngest person ever to receive an Honorary Academy Award.[79] Lee received the award as "a champion of independent film and an inspiration to young filmmakers". Frequent collaborators Denzel Washington, Samuel L. Jackson, and Wesley Snipes presented Lee with the award at a private ceremony at the Governors Awards.[80][81]

In 2019, Lee's film BlacKkKlansman went on to receive 6 Academy Award nominations. Lee himself was nominated for 3 Oscars for Lee for Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Adapted Screenplay. He went on to win the Best Adapted Screenplay, his first Academy Award.[82]

Two of his films have competed for the Palme d'Or award at the Cannes Film Festival, and of the two, BlacKkKlansman won the Grand Prix in 2018.[83]

Lee's films Do the Right Thing,[1] Malcolm X,[2] 4 Little Girls, She's Gotta Have It, and Bamboozled were each selected by the Library of Congress for preservation in the National Film Registry for being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[3]

On May 18, 2016, Lee delivered the Commencement address for The Johns Hopkins University Class of 2016.[84]

He has been named as the recipient of the Ebert Director Award at the TIFF Tribute Awards for the 2023 Toronto International Film Festival.[85]

In March 2024, Lee received a Board of Governor's Award from the American Society of Cinematographers.[86]

Personal life

Marriage

Lee met his wife, attorney Tonya Lewis Lee, in 1992, and they were married a year later in New York.[87] They have two children.[88][89]

When asked by the BBC whether he believed in God, Lee said: "Yes. I have faith that there is a higher being. All this cannot be an accident."[90] Lee continues to maintain an office in Fort Greene, Brooklyn, but he and his wife live on the Upper East Side of Manhattan.[91]

Sports

Spike Lee is a fan of the New York Knicks basketball team, the New York Yankees baseball team (although he grew up a New York Mets fan[92]), the New York Rangers ice hockey team, and the English football club Arsenal.[93][94] One of the documentaries in ESPN's 30 for 30 series, Winning Time: Reggie Miller vs. The New York Knicks, focuses partly on Lee's interaction with Miller at Knicks games in Madison Square Garden. In June 2003, Lee sought an injunction against Spike TV to prevent them from using his nickname; he claimed that because of his fame, viewers would think he was associated with the channel.[95][96][97] In March 2020, Lee and the security team at Madison Square Garden had a disagreement over which entrance to use to see the New York Knicks; Lee stated he would not attend the rest of the games for the season.[98][99] Spike Lee has also frequented New York Liberty games at Barclays Center, sitting courtside during the 2024 WNBA playoffs in a Sabrina Ionescu Jersey[100]

Politics

In May 1999, the New York Post reported that Lee made an inflammatory comment about Charlton Heston, president of the National Rifle Association of America (NRA), while speaking to reporters at the Cannes Film Festival. Lee was quoted as saying the National Rifle Association should be disbanded and, of Heston, someone should "Shoot him with a .44 Bull Dog."[101][102] Lee said he intended it as a joke. He was responding to coverage about whether Hollywood was responsible for school shootings. "The problem is guns", he said.[103] Republican House Majority Leader Dick Armey condemned Lee as having "nothing to offer the debate on school violence except more violence and more hate".[103]

In October 2005, Lee responded to a CNN anchor's question as to whether the government intentionally ignored the plight of black Americans during the 2005 Hurricane Katrina catastrophe by saying, "It's not too far-fetched. I don't put anything past the United States government. I don't find it too far-fetched that they tried to displace all the black people out of New Orleans."[104] In later comments, Lee cited the government's past including the Tuskegee Syphilis Study.[105][106]

In May 2020, Lee published a three-minute short film, NEW YORK NEW YORK, on Instagram[107] that was later featured on the city's official website.[108] Lee celebrated Joe Biden's victory over Donald Trump in the 2020 presidential election with champagne amid a crowd on the streets of Brooklyn.[109] Lee endorsed Kamala Harris in the 2024 United States presidential election and spoke at one of her campaign rallies on October 24, 2024.[110][111]

Legal issues

In March 2012, after the killing of Trayvon Martin, Spike Lee was one of many people who used Twitter to circulate a message that claimed to give the home address of the shooter George Zimmerman. The address turned out to be incorrect, causing the real occupants, Elaine and David McClain, to leave home and stay at a hotel due to numerous death threats.[112] Lee issued an apology and reached an agreement with the McClains, which reportedly included "compensation", with their attorney stating "The McClains' claim is fully resolved".[113][114] Nevertheless, in November 2013, the McClains filed a negligence lawsuit which accused Lee of "encouraging a dangerous mob mentality among his Twitter followers, as well as the public-at-large".[112][115] The lawsuit, which a court filing reportedly valued at $1.2 million, alleged that the couple suffered "injuries and damages" that continued after the initial settlement up through Zimmerman's trial in 2013.[112] A Seminole County judge dismissed the McClains' suit, agreeing with Lee that the issue had already been settled previously.[116]

Controversies

At the 2008 Cannes Film Festival, Lee, who was then making Miracle at St. Anna, about an all-black U.S. division fighting in Italy during World War II, criticized director Clint Eastwood for not depicting black Marines in his own World War II film, Flags of Our Fathers. Citing historical accuracy, Eastwood responded that his film was specifically about the Marines who raised the flag on Mount Suribachi at Iwo Jima, pointing out that while black Marines did fight at Iwo Jima, the U.S. military was racially segregated during World War II, and none of the men who raised the flag were black. He angrily said that Lee should "shut his face". Lee responded that Eastwood was acting like an "angry old man", and argued that despite making two Iwo Jima films back to back, Letters from Iwo Jima and Flags of Our Fathers, "there was not one black soldier in both of those films".[117][118][119] He added that he and Eastwood were "not on a plantation".[120] Lee later claimed that the event was exaggerated by the media and that he and Eastwood had reconciled through mutual friend Steven Spielberg, culminating in his sending Eastwood a print of Miracle at St. Anna.[121]

Lee has been criticized for his representation of women. For example, bell hooks said that he wrote black women in the same objectifying way that white male filmmakers write the characters of white women.[122] Rosie Perez, who was in an acting role for the first time as Tina in Do the Right Thing, said later that she was very uncomfortable with doing the nude scene in the film, saying, "I had a big problem with it, mainly because I was afraid of what my family would think...It wasn't really about taking off my clothes. But I also didn't feel good about it because the atmosphere wasn't correct."[123] Subsequently, Perez stated that Lee had offered an apology, and the two maintained their friendship.[124]

Over the course of his career Spike Lee has defended Woody Allen, Michael Jackson and Nate Parker, all of whom have been accused of sexual misconduct.[125][126][127][128][129]

References

- ^ a b "CNN - U.S. film registry adds 25 new titles - November 16, 1999". www.cnn.com.

- ^ a b "Spike Lee's 'Malcolm X' among 25 film registry picks". January 3, 2011.

- ^ a b Chow, Andrew R. (December 11, 2019). "See the 25 New Additions to the National Film Registry, From Purple Rain to Clerks". Time. New York, NY. Retrieved December 11, 2019.

- ^ "Spike Lee wins $300,000 Gish Prize". BBC News. Retrieved April 30, 2014.

- ^ "Spike Lee awarded $300,000 Gish Prize". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 30, 2014.

- ^ "Spike Lee Biography (1956?-)". Film Reference. Retrieved August 14, 2010.

- ^ "7". Who Do You Think You Are?. Season 1. Episode 7. April 30, 2010. NBC.

- ^ Saad, Megan (January 3, 2014). "Spike Lee's Brother Passes Away At 55". Vibe. Retrieved May 25, 2023.

- ^ "SHELTON "SPIKE" LEE '79". Morehouse College. April 9, 2012. Archived from the original on May 6, 2012. Retrieved April 9, 2012.

- ^ "Oeuvre: Spike Lee: Joe's Bed-Stuy Barbershop: We Cut Heads". Spectrum Culture. March 15, 2012. Archived from the original on March 17, 2012. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- ^ "She's Gotta Have It (1986)". Box Office Mojo. August 26, 1986. Retrieved June 13, 2011.

- ^ Scott, A. O. (2007). "She's Gotta Have It". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 27, 2007. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ^ "Siskel & Ebert 1989-Best of 1989 (2of2)". YouTube. December 17, 2010. Retrieved April 29, 2015.

- ^ Roger Ebert. "The Great Movies". rogerebert.com. Retrieved April 29, 2015.

- ^ "Kim Basinger Rips Academy for Snubbing Spike Lee's Film". Jet. No. 27. Ebony Media Operations. April 16, 1990.

- ^ Higgins, Bill (May 12, 2018). "Hollywood Flashback: A Snubbed Spike Lee Trashed Wim Wenders at Cannes in 1989". The Hollywood Reporter.

- ^ Hill, Logan (April 7, 2008). "Q&A with Spike Lee on Making 'Do the Right Thing'". New York. Retrieved June 13, 2011.

- ^ James, Caryn (August 16, 1990). "Spike Lee's Jews and the Passage from Benign Cliche into Bigotry". The New York Times. Retrieved December 1, 2009.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (December 31, 1992). "The Best 10 Movies of 1992". rogerebert.com. Retrieved March 15, 2011.

- ^ Anderson, Jeffrey M. "The Best Films of the 1990s". Combustible Celluloid. Retrieved June 21, 2010.

- ^ DVDTalk.com. "Spike Lee on Malcolm X". Dvdtalk.com. Retrieved July 18, 2010.

- ^ "The 70th Academy Awards | 1998". Oscars.org | Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. October 5, 2014.

- ^ "2017 National Film Registry Is More Than a 'Field of Dreams'". Library of Congress. Retrieved December 13, 2017.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (December 16, 2009). "25th Hour Review". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on March 22, 2010. Retrieved July 11, 2010.

- ^ Dunn, Brian (December 26, 2009). "A. O. Scott's Ten Best Films of the 2000s". Archived from the original on March 19, 2011. Retrieved November 29, 2011.

- ^ Roeper, Richard (January 1, 2010). "Roeper's best films of the decade". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on April 21, 2010. Retrieved July 11, 2010.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (December 30, 2009). "The best films of the decade". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on May 28, 2010. Retrieved July 11, 2010.

- ^ "The 21st Century's 100 greatest films". BBC. August 23, 2016. Retrieved October 14, 2016.

- ^ "25th Hour (2002)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved June 18, 2013.

- ^ "Empire's Inside Man Movie Review". Empire. Bauer Consumer Media. Archived from the original on June 17, 2013. Retrieved January 21, 2013.

- ^ ""Spike Lee to Receive the Wexner Prize"; Wexner Center for the Arts". Wexarts.org. Archived from the original on June 14, 2011. Retrieved June 13, 2011.

- ^ Chris Lee (September 18, 2013). "Spike Lee awarded $300,000 Gish Prize". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 19, 2013.

- ^ "Spike Lee, Debbie Reynolds And Gena Rowlands To Receive Academy's 2015 Governors Awards". August 27, 2015.

- ^ "Spike Lee receives an Honorary Award at the 2015 Governors Awards". YouTube. November 15, 2015. Archived from the original on October 28, 2021. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- ^ Plunkett, Luke (June 4, 2015). "Spike Lee Is Writing A Video Game Campaign". Kotaku. Retrieved June 6, 2015.

- ^ "Chi-Raq (2015)". Rotten Tomatoes. December 4, 2015. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- ^ "Spike Lee's BlacKkKlansman wins Grand Prix award from Cannes". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- ^ "Rotten Tomatoes – BLACKKKLANSMAN". Rotten Tomatoes. August 10, 2018. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- ^ ""Movies Fall Apart a Million Times": The Director Roundtable". The Hollywood Reporter. December 14, 2018. Retrieved August 4, 2020.

- ^ ""BlacKkKlansman" wins Best Adapted Screenplay". March 25, 2019 – via www.youtube.com.

- ^ "The 91st Academy Awards | 2019". Oscars.org | Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. April 15, 2019.

- ^ "Oscars 2019 Spike Lee says Green Book 'not my cup of tea'". YouTube. February 25, 2019. Archived from the original on October 28, 2021. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- ^ "Spike Lee on 'Green Book's' Controversial Oscars Best Picture Win". The Hollywood Reporter. February 24, 2019. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- ^ "Spike Lee Gets 'Driving Miss Daisy' Deja Vu From 'Green Book' Win: 'Ref Made a Bad Call'". The Wrap. February 24, 2019. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- ^ Morris, Wesley (January 23, 2019). "Why Do the Oscars Keep Falling for Racial Reconciliation Fantasies?". The New York Times. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- ^ Brown, Lane (June 9, 2020). "Spike Lee's Forever War: How the Vietnam War epic Da 5 Bloods became one of the most ambitious films of his career". Vulture. Retrieved June 10, 2020.

- ^ Keegan, Rebecca (June 11, 2020). "Spike Lee on the Challenge of Bringing Netflix's 'Da 5 Bloods' to the Screen". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- ^ Sharf, Zack (May 7, 2020). "Spike Lee's 'Da 5 Bloods' to Stream on Netflix in June, but It's Still Eligible for Oscars". IndieWire. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- ^ Josef Adalian (July 23, 2011). "Breaking: The Wire's Michael K. "Omar" Williams Is Headed to Community". Retrieved July 23, 2011.

- ^ "Da 5 Bloods (2020)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- ^ "Da 5 Bloods Reviews". Metacritic. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- ^ Schaffstall, Katherine (June 10, 2020). "'Da 5 Bloods': What the Critics Are Saying". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr. (November 17, 2020). "Spike Lee Sets eOne Film Musical On Pfizer's Pre-COVID Miracle Drug: Viagra". Deadline. Retrieved December 12, 2021.

- ^ "Spike Lee Signs Multiyear Film Deal with Netflix to Direct and Produce". December 16, 2021.

- ^ "Spike Lee and Denzel Washington Are Remaking Akira Kurosawa's 'High and Low' with Apple and A24". IndieWire. February 8, 2024. Retrieved February 9, 2024.

- ^ "Professor web page". NYU Tish Directory. NYU. Retrieved November 25, 2015.

- ^ Sandra Gonzalez (February 13, 2019). "Spike Lee strives to be on the right side of history".

- ^ Elliott, Stuart (July 22, 1991). "THE MEDIA BUSINESS: [sic] Advertising; Levi and Spike Lee Return In 'Button Your Fly' Part 2". The New York Times.

- ^ "Kindred, Dave; "Mars points NBA to next Milky Way – advertising character Mars Blackmon"; findarticles.com; July 21, 1997". Findarticles.com. July 21, 1997. Archived from the original on May 26, 2012. Retrieved June 13, 2011.

- ^ a b "Chucksconnection.com". Archived from the original on August 11, 2006.

- ^ "Converse Splits With Butler". Retrieved February 15, 2018.

- ^ "Jaguar enlists Spike Lee to help diversify market". Retrieved February 15, 2018.

- ^ JOHNSON, GREG (July 7, 1995). "Basketball Stars Team Up for Taco Bell Ad Campaign : Marketing: Shaquille O'Neal and Hakeem Olajuwon go one-on-one in television commercials that follow up provocative teasers in several papers". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved February 15, 2018.

- ^ "BEN & JERRY'S & SPIKE & SMOOTH ICE CREAMS' FIRST BIG AD EFFORT BOASTS A SOCIAL CONSCIENCE". Retrieved February 15, 2018.

- ^ "Spike Lee Biography". Yahoo! Movies. Retrieved February 10, 2009.

- ^ Maane Khatchatourian (November 29, 2013). "'Oldboy' Will Likely Be Trampled by New Releases in Thanksgiving Rush". Variety. Retrieved August 4, 2016.

- ^ "Do the Right Thing". The Criterion Collection.

- ^ "Bamboozled". The Criterion Collection.

- ^ "Spike Lee's Secret Weapon: The Double Dolly Shot". August 2, 2018.

- ^ "Spike Lee Breaks Down His Film Heroes". GQ. August 17, 2018. Archived from the original on October 28, 2021. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- ^ "Student Film Award Winners" (PDF). Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. p. 10. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 5, 2004. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- ^ "Past Winners". Black Reel Awards. Archived from the original on February 26, 2016. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- ^ "Prizes & Honours 1997". Berlin International Film Festival. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- ^ Nickolai, Nate (February 10, 2019). "BAFTA Awards 2019: Complete Winners List". Variety. Retrieved February 12, 2019.

- ^ "The 62nd Academy Awards | 1990". Oscars.org | Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. October 5, 2014.

- ^ "Dead Poets Society Wins Original Screenplay: 1990 Oscars". August 11, 2014 – via www.youtube.com.

- ^ "Honorary Award". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. July 17, 2014. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- ^ Gonzalez, Sandra (January 22, 2019). "Spike Lee earns first Oscar nomination for directing". CNN. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- ^ "Spike Lee to get honorary Oscar 25 years after Do the Right Thing". The Guardian. August 28, 2015. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- ^ "Spike Lee calls for diversity as he receives honorary Oscar". BBC News. November 15, 2015. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- ^ "Honorary Oscar Recipient Spike Lee Also a Frequent Critic of the Academy". The Hollywood Reporter. August 27, 2015. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- ^ Deb, Sopan (February 24, 2019). "Spike Lee Won an Oscar. Read His Passionate Speech". The New York Times. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- ^ Debruge, Peter (May 19, 2018). "Japanese Director Hirokazu Kore-eda's 'Shoplifters' Wins Palme d'Or at Cannes". Variety. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ^ Bryan Stevenson (May 18, 2016). "Filmmaker Spike Lee speaks at Johns Hopkins graduation". Johns Hopkins University. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

I wish you could be graduating into a world of peace, light, and love, but that's not the case

- ^ "Spike Lee and Pedro Almodóvar to receive TIFF Tribute Awards, while ‘Dicks: The Musical’ to open Midnight Madness". Toronto Star, August 3, 2023.

- ^ "ASC to Honor Spike Lee with Board of Governors Award". American Cinematographer. February 6, 2024. Retrieved February 26, 2024.

- ^ Rothkranz, Lindzy (February 13, 2015). "Tonya Lewis Lee, Spike's Wife: 5 Fast Facts You Need to Know". Heavy.

- ^ "Milestones". Time. December 19, 1994.

- ^ am (October 27, 2009). "Black Celebrity Kids, babies, and their Parents » SPIKE LEE AND KIDS ATTEND MICHAEL JACKSON'S THIS IS IT PREMIERE". Blackcelebkids.Com. Archived from the original on January 18, 2013. Retrieved August 28, 2012.

- ^ Papamichael, Stella. "Calling the Shots: No.21: Spike Lee". BBC. Retrieved March 23, 2017.

- ^ Kachka, Boris (March 12, 2001). "Real Estate 2001: Neighborhood Profiles - Nymag". New York Magazine.

- ^ Berg, Aimee, ed. (October 27, 2015). "Spike Lee has love, respect for NYC Marathon runners". USA Today. Retrieved June 11, 2022.

- ^ "Arsenal Supporters Series: Spike Lee". Arsenal.theoffside.com. Archived from the original on December 2, 2009. Retrieved August 14, 2010.

- ^ Oct 29, foxsports; ET, 2011 at 1:00a (October 29, 2011). "Spike Lee makes the switch to NHL". FOX Sports. Retrieved March 13, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Romano, Allison (April 21, 2003). "TNN Hopes Mainly Men Will Watch "Spike TV"s". Archived from the original on May 6, 2009. Retrieved August 31, 2007.

- ^ "Nexttv". NextTV. Archived from the original on June 8, 2008. Retrieved December 20, 2021.

- ^ "Spike sues over channel name". BBC News. June 4, 2003. Retrieved May 23, 2010.

- ^ "Knicks call Spike Lee employee entrance dispute 'laughable'". NBC. March 3, 2020. Retrieved August 4, 2020.

- ^ "Here's Why Spike Lee and the New York Knicks Are Feuding Right Now". Newsweek. March 3, 2020. Retrieved August 4, 2020.

- ^ "Kelsey Plum and Sabrina Ionescu Have Drastically Different Spike Lee Experiences During Aces-Liberty". Women's Fastbreak On SI. September 29, 2024. Retrieved September 30, 2024.

- ^ "Spike Lee Says Remark About Shooting Heston Was A Joke – Chicago Tribune". Articles.chicagotribune.com. May 28, 1999. Archived from the original on May 18, 2010. Retrieved February 13, 2013.

- ^ "Heston was always a man of his words". Los Angeles Times. April 8, 2008. Archived from the original on November 13, 2013. Retrieved February 13, 2013.

- ^ a b "Living foot to mouth". Salon.com. May 28, 1999. Archived from the original on June 23, 2008. Retrieved June 13, 2011.

- ^ "Milwaukee Journal Sentinel – Google News Archive Search". news.google.com.

- ^ "All about Spike Lee's latest film". SooToday.com. August 14, 2006.

- ^ "Clip of Lee expressing his views of the Hurricane Katrina and Tuskegee matters on Real Time with Bill Maher". YouTube. March 6, 2007. Archived from the original on October 28, 2021. Retrieved June 13, 2011.

- ^ "Spike Lee made an emotional 3-minute film dedicated to New York City". CNN. May 8, 2020. Retrieved May 23, 2020.

- ^ "Experience: Spike Lee New York City". visittheusa.com. Retrieved November 8, 2020.

- ^ "Watch: Spike Lee Pops a Bottle of Champagne in Middle of Brooklyn Street to Celebrate Joe Biden's Win". PopCulture. November 7, 2020. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved November 8, 2020.

- ^ "VP Kamala Harris in Atlanta for rally with former President Obama, Spike Lee". FOX 5 Atlanta. October 22, 2024. Retrieved October 25, 2024.

- ^ "Spike Lee, Samuel L. Jackson, Tyler Perry to join Kamala Harris at metro Atlanta event". Atlanta News First. October 24, 2024. Retrieved October 25, 2024.

- ^ a b c "Elderly Couple Sues Spike Lee Over Tweet". The Smoking Gun. November 8, 2013. Retrieved November 11, 2013.

- ^ "Spike Lee apologizes for retweeting wrong Zimmerman address". CNN. March 29, 2012. Retrieved March 29, 2012.

- ^ Muskal, Michael (March 29, 2012). "Trayvon Martin: Spike Lee settles with family forced to flee home". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 1, 2012.

- ^ Colleen Curry (November 11, 2013). "Spike Lee Sued Over George Zimmerman Tweet". ABC News. Retrieved November 11, 2013.

- ^ TV, Centric. "Judge Dismisses Lawsuit Against Spike Lee Over George Zimmerman Tweet – What's Good – Entertainment – Articles – Centric".

- ^ Marikar, Sheila (June 6, 2008). "Spike Strikes Back: Clint's 'an Angry Old Man'". ABC News.

- ^ "Eastwood hits back at Lee claims". BBC News. June 6, 2008. Retrieved August 4, 2009.

- ^ Lyman, Eric J. (May 21, 2008). "Lee calls out Eastwood, Coens over casting". The Hollywood Reporter (8): 3, 24.

- ^ Wainwright, Martin (June 9, 2008). "'We're not on a plantation, Clint'". The Guardian.

- ^ ""Access Exclusive: Spike Lee On Clint Eastwood: 'We're Cool'" OMG!/Yahoo! September 6, 2008". Archived from the original on January 5, 2010.

- ^ hooks, bell (October 10, 2014). Black Looks. doi:10.4324/9781315743226. ISBN 978-1-315-74322-6.

- ^ Udovitch, Mim (June 25, 2000). "The Pressure To Take It Off". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ "Rosie Perez on Making Peace with Spike Lee, Bombing Her 'Matrix' Audition and Why Hollywood's Latino Representation Still 'Sucks'". March 29, 2023.

- ^ "Nate Parker Apologizes for Being 'Tone Deaf,' Spike Lee Defends the Disgraced Director". IndieWire. September 2019. Retrieved January 19, 2020.

- ^ Aquillina, Tyler (June 13, 2020). "Spike Lee defends Woody Allen against 'this cancel thing': 'Woody's a friend of mine'". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved July 21, 2020.

- ^ Bennett, Anita (June 13, 2020). "Spike Lee Walks Back Comments Defending "Friend" Woody Allen Against Cancel Culture". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved July 21, 2020.

- ^ "Spike Lee apologizes after appearing to defend Woody Allen". CNN. June 15, 2020. Retrieved August 4, 2020.

- ^ "'My words were wrong': Spike Lee apologizes after defending Woody Allen". The Guardian. June 14, 2020. Retrieved August 4, 2020.

External links

- Spike Lee at IMDb

- Spike Lee on Twitter

- Spike Lee on Charlie Rose

- Spike Lee collected news and commentary at The New York Times

- Spike Lee collected news and commentary at The Guardian

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Ubben Lecture at DePauw University

- Criterion Collection Essay on Spike Lee's Do the Right Thing

- Lee's Lens Exposes Inequalities, but he's no Revolutionary by Brendan Kelly, Canwest, April 11, 2009

- Interview with Politico Magazine February 7, 2019

- Spike Lee

- 1957 births

- 20th-century African-American male actors

- 20th-century American male actors

- 20th-century American male writers

- 20th-century American screenwriters

- 21st-century African-American male actors

- 21st-century American male actors

- 21st-century American male writers

- 21st-century American screenwriters

- Academy Honorary Award recipients

- African-American film directors

- African-American film producers

- African-American screenwriters

- African-American television producers

- American documentary film directors

- American film producers

- American male film actors

- American male screenwriters

- American music video directors

- Best Adapted Screenplay Academy Award winners

- Best Adapted Screenplay BAFTA Award winners

- César Honorary Award recipients

- Culture of Brooklyn

- Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

- Film directors from New York City

- John Dewey High School alumni

- Living people

- Male actors from Atlanta

- Male actors from Brooklyn

- Male actors from Manhattan

- Morehouse College alumni

- People from Fort Greene, Brooklyn

- People from the Upper East Side

- Primetime Emmy Award winners

- Screenwriters from Georgia (U.S. state)

- Screenwriters from New York (state)

- Television commercial directors

- Television producers from New York City

- Tisch School of the Arts alumni

- Tisch School of the Arts faculty

- Writers from Atlanta

- Writers from Brooklyn

- Writers from Manhattan

- New York Knicks

- African-American company founders