Decadence

Decadence was late-19th-century movement emphasizing the need for sensationalism, egocentricity; bizarre, artificial, perverse, and exotic sensations and experiences. By extension, it may refer to a decline in art, literature, science, technology, and work ethics, or (very loosely) to self-indulgent behavior.

Usage of the term sometimes implies moral censure, or an acceptance of the idea, met with throughout the world since ancient times, that such declines are objectively observable and that they inevitably precede the destruction of the society in question; for this reason, modern historians use it with caution. The word originated in Medieval Latin (dēcadentia), appeared in 16th-century French, and entered English soon afterwards. It bore the neutral meaning of decay, decrease, or decline until the late 19th century, when the influence of new theories of social degeneration contributed to its modern meaning.

The idea that a society or institution is declining is called declinism. This may be caused by the predisposition, caused by cognitive biases such as rosy retrospection, to view the past more favourably and future more negatively.[1] Declinism has been described as "a trick of the mind" and as "an emotional strategy, something comforting to snuggle up to when the present day seems intolerably bleak." Other cognitive factors contributing to the popularity of declinism may include the reminiscence bump as well as both the positivity effect and negativity bias.

In literature, the Decadent movement began in France's fin de siècle intermingling with Symbolism and the Aesthetic movement while spreading throughout Europe and the United States.[2] The Decadent title was originally used as a criticism but it was soon triumphantly adopted by some of the writers themselves.[3] The Decadents praised artifice over nature and sophistication over simplicity, defying contemporary discourses of decline by embracing subjects and styles that their critics considered morbid and over-refined.[4] Some of these writers were influenced by the tradition of the Gothic novel and by the poetry and fiction of Edgar Allan Poe.[5]

History

[edit]Ancient Rome

[edit]Decadence is a popular criticism of the culture of the later Roman Empire's elites, seen also in much of its earlier historiography and 19th and early 20th century art depicting Roman life. This criticism describes the later Roman Empire as reveling in luxury, in its extreme characterized by corrupting "extravagance, weakness, and sexual deviance", as well as "orgies and sensual excesses".[6][7][8][9][10][excessive citations]

Victorian-era Artwork on Roman Decadence

[edit]According to Professor Joseph Bristow of UCLA, decadence in Rome and the Victorian-era movement are connected through the idea of "decadent historicism."[11] In particular, decadent historicism refers to the "interest among…1880s and 1890s writers in the enduring authority of perverse personas from the past" including the later Roman era.[11] As such, Bristow's argument references how Heliogabalus, the title subject of Simeon Solomon's painting Heliogabalus, High Priest of the Sun (1866), was "a decadent icon" for the Victorian movement.[11] Bristow also notes that "[t]he image [of the painting] summons many qualities linked with fin-de-siècle decadence [alongside his]…queerness[,]" thus "inspir[ing] late-Victorian writers [as]…they…imagine anew sexual modernity."[11]

Heliogabalus is also the subject of The Roses of Heliogabalus (1888) by Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, which, according to Professor Rosemary Barrow, represents "the artist['s]…most glorious revel in Roman Decadence."[12] To Barrow, "[t]he authenticity of the [scene]…perhaps had little importance for the artist[, meaning that] its appeal is the entertaining and extravagant vision it gives of later imperial Rome."[12] Barrow also makes a point to mention "that Alma-Tadema’s Roman-subject paintings [tend to]…make use of historical, literary and archaeological sources" within themselves.[12] Thus, the presence of roses within the painting as opposed to the original "'violets and other flowers'" of the source material emphasizes how "the Roman world…h[eld] extra connotations of revelry and luxuriant excess" about them.[12]

Decadent movement

[edit]

Decadence was the name given to a number of late nineteenth-century writers who valued artifice over the earlier Romantics' naïve view of nature. Some of them triumphantly adopted the name, referring to themselves as Decadents. For the most part, they were influenced by the tradition of the Gothic novel and by the poetry and fiction of Edgar Allan Poe, and were associated with Symbolism and/or Aestheticism.

This concept of decadence dates from the eighteenth century, especially from Montesquieu and Wilmot. It was taken up by critics as a term of abuse after Désiré Nisard used it against Victor Hugo and Romanticism in general. A later generation of Romantics, such as Théophile Gautier and Charles Baudelaire took the word as a badge of pride, as a sign of their rejection of what they saw as banal "progress." In the 1880s, a group of French writers referred to themselves as Decadents. The classic novel from this group is Joris-Karl Huysmans' Against Nature, often seen as the first great decadent work, though others attribute this honor to Baudelaire's works.

In Britain and Ireland the leading figure associated with the Decadent movement was Irish writer, Oscar Wilde. Other significant figures include Arthur Symons, Aubrey Beardsley and Ernest Dowson.

The Symbolist movement has frequently been confused with the Decadent movement. Several young writers were derisively referred to in the press as "decadent" in the mid-1880s. Jean Moréas' manifesto was largely a response to this polemic. A few of these writers embraced the term while most avoided it. Although the aesthetics of Symbolism and Decadence can be seen as overlapping in some areas, the two remain distinct.

1920s Berlin

[edit]This "fertile culture" of Berlin extended onwards until Adolf Hitler rose to power in early 1933 and stamped out any and all resistance to the Nazi Party. Likewise, the German far-right decried Berlin as a haven of degeneracy. A new culture had developed in and around Berlin throughout the previous decade, including architecture and design (Bauhaus, 1919–33), a variety of literature (Döblin, Berlin Alexanderplatz, 1929), film (Lang, Metropolis, 1927, Dietrich, Der blaue Engel, 1930), painting (Grosz), and music (Brecht and Weill, The Threepenny Opera, 1928), criticism (Benjamin), philosophy/psychology (Jung), and fashion.[citation needed] This culture was considered decadent and disruptive by rightists.[13]

Film was making huge technical and artistic strides during this period of time in Berlin, and gave rise to the influential movement called German Expressionism. "Talkies", the sound films, were also becoming more popular with the general public across Europe, and Berlin was producing very many of them.

Berlin in the 1920s also proved to be a haven for English-language writers such as W. H. Auden, Stephen Spender and Christopher Isherwood, who wrote a series of 'Berlin novels', inspiring the play I Am a Camera, which was later adapted into a musical, Cabaret, and an Academy Award winning film of the same name. Spender's semi-autobiographical novel The Temple evokes the attitude and atmosphere of the place at the time.

Decadent Nihilistic Art

[edit]

The philosophy of decadence comes from the work of German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer (1788–1860),[14] however, Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900), a specific philosopher of decadence, conceptualized modern decadence on a more influential scale. Holding decadence to be in any condition, ultimately limiting what something or someone can be, Nietzsche used his exploration in nihilism to critique traditional values and morals that threatened the decline in art, literature, and science. Nihilism, generally, is the rejection of moral principles, ultimately believing that life is meaningless. Nihilism, for Nietzsche, was the ultimate fate of Western civilization as old values lost their influence and purpose, in turn, disappeared among society. Predicting a rise in decadence and aesthetic nihilism, creators would renounce the pursuit of beauty and instead welcome the incomprehensible chaos. In art, there have been movements connected to nihilism, such as cubism and surrealism, that pushes for abandoned viewpoints to ultimately tap into the potential of one's conscious mind.

Because of this, paintings like 1875-76's "L’Absinthe" by Edgar Degas and 1915's "Black Square" by Kazimir Malevich were created. L’Absinthe, which first showed in 1876, was mocked and called disgusting when panned by critics. Some say the painting is a blow to morality, as a glass filled with Absinthe, an alcoholic drink, rests in front of a woman at a table. Taken to be in bad faith and quite uncouth, Degas's art took decadence as a way to portray ambiguity in random subjects that seem to be drifting between depression and euphoria. Using nihilism in a synonymously way, Degas denoted his paintings to a general mood of despair, mainly at existence as a whole. Comparing this piece to Kazimir Malevich's "Black Square," abstract nihilistic art in the Western tradition was only beginning to take shape as the 20th century came about. Malevich's perception of this piece embraced a philosophy connected to Suprematism – a new realism in painting that evokes non-objectivity to experience "white emptiness of a liberated nothing," as said by Malevich himself. In nihilism, life has, in a sense, no truth, therefore no action is objectively preferable to another. Malevich's decadent painting shows the complete abandonment of depicting reality, and instead creates his own world of new form. When the painting was first exhibited, the public was in chaos, as society was in its first World War and Malevich reflected a new social revolution as a symbol of a new tomorrow, disregarding the past to move forward. Because of this painting and Degas's, decadence can be portrayed as a physiological foundation for nihilism, bringing out a term called "Decadent Nihilism:" existing beyond the world, and that of vain virtues. According to Nietzsche, Western metaphysical and nihilistic thought is decadent because of its confirmation from 'others' (apart from oneself) based on ideas of a nihilistic God. The extreme position an artist takes is what makes their pieces decadent.

Decadent Aesthetics

[edit]Controversy

[edit]Vladimir Nabokov's Lolita (1955)

Aesthetics falling under the category of decadence often include controversy. An example of a controversial style founded through decadent literary influence is the novel, Lolita, by Vladimir Nabokov, a Russian-American citizen. Lolita, while expressing the prose through a pedophile's narration, directly expresses Nabokov's discourse with decadent literature. According to Will Norman from the University of Kent, the novel makes many references to prominent historical figures related to decadence, such as Edgar Allan Poe and Charles Baudelaire.[15] Norman states, "... Lolita emerges as the risky reinstatement of a transatlantic decadent tradition, in which the failure of temporal and ethical containment disrupts a dominant narrative of modernism's history in American letters".[15] Lolita purposefully exemplifies a moral decline, while simultaneously disregarding the ethics of Nabokov’s time. The emphasis on its temporal standing in history captures an intermediate state of decadent literature itself. Norman describes that "... Nabokov reproduces the tension between American regionalism and modernist cosmopolitanism in his own 'Edgar H. Humbert', as the European aesthete embarks on his road-trip with Dolores...".[15] The text exemplifies Nabokov's desire to replicate the many social disparities of American culture while using his character, H. Humbert, to demonstrate a lack of moral judgement. Norman continues, "Nabokov's text positions itself as the dynamic historical agent, importing Poe wholesale (from caricature through to complex literary intellectual) into the present and facilitating his critique in the hands of the reader".[15] Leaving the judgement in the hands of the reader, Nabokov uses Lolita to work through the complexities that decadence presents for ethical or moral obligations to society. Norman concludes, "Lolita joins American works such as William Faulkner's The Sound and the Fury (1929) and F. Scott Fitzgerald's Tender Is the Night (1934) which assimilate themes of incest and sexual pathology into their decadent aesthetics, with the effect of bringing European temporalities into conflict with American social modernity".[15] Using a controversial method, Nabokov employs decadent aesthetics to document a moment of historical transition.

Women in Decadence

Not only do the stylistic choices of literature in decadence cause ethical debate, but the presence of women in literature also causes controversy in politics. Viola Parente-Čapková, a Lecturer from the university in Prague, Czech Republic, argues that women writers following decadent literary structure have been overlooked due to their simultaneous influence of the feminist movement.[16] The belief that women could not separate morality from their writing due to their purposeful prose to argue for women's rights suggests a theme of misogyny, in which men excluded women from being considered Decadent writers because of the possibility of a desire for social change.

Social Change

Decadence offers a world-view, in that "it is an ideological phenomenon originating in the experience of a particular group, and it became the aesthetics of the upper-middle class".[17] Changes in European industrialization and urbanization led to the development of the proletariat, nuclear family, and entrepreneurial class . The values of Decadence formed as an opposition to "those of an earlier and supposedly more vital bourgeoisie".[17] Aesthetically, progress turns into decay, activity becomes play instead of goal-oriented work, and art becomes a way of life. To individuals that observe the changes in social structure after rapid industrialization, the idea of progress becomes something to rebel against, because this real-world progress seems to be leaving them behind.

Modern-day perspectives

[edit]Postmodernist Connection to Decadence

[edit]Nearly a century after the supposed end of the decadent period itself, the spirit and drive of it continued in the next end of the century. Unknowingly following in the footsteps of the decadents before them, postmodernists have subscribed to many of the same habits. Both groups have found themselves simultaneously exhausted by all the new experiences of society while still putting all their efforts into experiencing it all. The postmodernist is simultaneously aware of their desire for modernist disintegration all while enjoying the products of their dying predecessor.[18] This ravenous eye for the new is reflective of the lives of the practicing decadent, where they too enjoyed all the new experiences offered by their own time's modernity. Both events were deeply intertwined with expanding globalization. As seen in the lives of decadents in their literary and visual art pursuit and creation, so too has the postmodernist been given more global connection and experience.[18] During the rise of postmodernism, there has been a clear concentration of power and wealth that supported globalization. This resurgence of power to apply has restructured the desires of the disintegration-loving postmodernist, indulging themselves in all the newness of globalized life.[18] This renewed interest in a global view of the world brought along a renewed interest in different forms of artistic representation as well.

Modernism tends to belittle popular culture through its oppressive nature, which can be seen as elitist and controlling, as it privileges certain works of art above others. As a result, postmodern artists and writers developed a contempt for the canon, rejecting tradition and essentialism. This disdain for privilege extended to the fields of philosophy, science, and of course, politics. Pierre Bourdieu provides some insight into the attitudes of this new sub-class and its relation to post-modern theorists, embodied through students of bourgeois descent.[18] They began to pursue their artistic interests at their schools after being shadowed academically. They are victims of verdicts which, like those of the school, appeal to reason and science to block off the paths leading (back) to power, and are quick to denounce science, power, the power of science, and above all perhaps a power which, like the triumphant technology of the moment, appeals to science to legitimate itself.[18] This postmodern way of thought is guided by an anti-institutional temperament that flees competitions and hierarchies. These systems allow art to become confined by labels – postmodern work is difficult to define. In the name of the fight against 'taboos' and the liquidation of 'complexes' they adopt the most external and most easily borrowed aspects of the intellectual life-style, liberated manners, cosmetic or sartorial outrages, emancipated poses and postures, and systematically apply the cultivated disposition to not-yet-legitimate culture (cinema, strip cartoons, the underground), to every-day life (street art), the personal sphere (sexuality, cosmetics, child-rearing, leisure) and the existential (the relation to nature, love, death).[18] Their craft evolves into a way of being that directly criticizes modernist attitudes, and enables postmodern artists and writers with a newfound sense of freedom through rebellion.

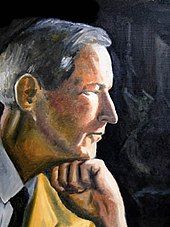

Jacques Barzun

[edit]

The historian Jacques Barzun (1907–2012) gives a definition of decadence which is independent from moral judgement. In his bestseller From Dawn to Decadence: 500 Years of Western Cultural Life[19] (published 2000) he describes decadent eras as times when "the forms of art as of life seem exhausted, the stages of development have been run through. Institutions function painfully." He emphasizes that "decadent" in his view is "not a slur" but "a technical label".

With reference to Barzun, New York Times columnist Ross Douthat characterizes decadence as a state of "economic stagnation, institutional decay and cultural and intellectual exhaustion at a high level of material prosperity and technological development".[20] Douthat sees the West in the 21st century in an "age of decadence", marked by stalemate and stagnation. He is the author of the book The Decadent Society, published by Simon & Schuster in 2020.

Pria Viswalingam

[edit]Pria Viswalingam, an Australian documentary and film maker, sees the western world in decay since the late 1960s. Viswalingam is the author of the six-episode documentary TV series Decadence: The Meaninglessness of Modern Life, broadcast in 2006 and 2007, and the 2011 documentary film Decadence: The Decline of the Western World.

According to Viswalingam, western culture started in 1215 with the Magna Carta, continued to the Renaissance, the Reformation, the founding of America, the Enlightenment and culminated with the social revolutions of the 1960s.[21]

Since 1969, the year of the moon landing, the My Lai massacre, the Woodstock Festival and the Altamont Free Concert, „decadence depicts the west's decline". As symptoms he names increasing suicide rates, addiction to anti-depressants, exaggerated individualism, broken families and a loss of religious faith as well as „treadmill consumption, growing income-disparity, b-grade leadership" and money as the only benchmark for value.

Use in Marxism

[edit]Leninism

[edit]According to Vladimir Lenin, capitalism had reached its highest stage and could no longer provide for the general development of society. He expected reduced vigor in economic activity and a growth in unhealthy economic phenomena, reflecting capitalism's gradually decreasing capacity to provide for social needs and preparing the ground for socialist revolution in the West. Politically, World War I proved the decadent nature of the advanced capitalist countries to Lenin, that capitalism had reached the stage where it would destroy its own prior achievements more than it would advance.[22]

One who directly opposed the idea of decadence as expressed by Lenin was José Ortega y Gasset in The Revolt of the Masses (1930). He argued that the "mass man" had the notion of material progress and scientific advance deeply inculcated to the extent that it was an expectation. He also argued that contemporary progress was opposite the true decadence of the Roman Empire.[23]

Left communism

[edit]Decadence is an important aspect of contemporary left communist theory. Similar to Lenin's use of it, left communists, coming from the Communist International themselves started in fact with a theory of decadence in the first place, yet the communist left sees the theory of decadence at the heart of Marx's method as well, expressed in famous works such as The Communist Manifesto, Grundrisse, Das Kapital but most significantly in Preface to the Critique of Political Economy.[24]

Contemporary left communist theory defends that Lenin was mistaken on his definition of imperialism (although how grave his mistake was and how much of his work on imperialism is valid varies from groups to groups) and Rosa Luxemburg to be basically correct on this question, thus accepting capitalism as a world epoch similarly to Lenin, but a world epoch from which no capitalist state can oppose or avoid being a part of. On the other hand, the theoretical framework of capitalism's decadence varies between different groups while left communist organizations like the International Communist Current hold a basically Luxemburgist analysis that makes an emphasis on the world market and its expansion, others hold views more in line with those of Vladimir Lenin, Nikolai Bukharin and most importantly Henryk Grossman and Paul Mattick with an emphasis on monopolies and the falling rate of profit.

See also

[edit]- Acedia

- Anomie

- Behavioral sink

- Bread and circuses

- Buraiha

- Competence (human resources)

- Kleptocracy

- Late capitalism

- Moral relativism

- Privilege hazard

- Societal collapse

- Twilight of the Idols

- The Decline of the West

- Degenerate art

References

[edit]- ^ The Oxford Dictionary of American Political Slang edited by Grant Barrett, p. 90.

- ^ Smith, James M. (1953). "Concepts of Decadence in Nineteenth-Century French Literature". Studies in Philology. 50 (4): 640–651. ISSN 0039-3738. JSTOR 4173078.

- ^ Kaminsky, Alice R. (1976). "The Literary Concept of Decadence". Nineteenth-Century French Studies. 4 (3): 371–384. ISSN 0146-7891. JSTOR 23536184.

- ^ Drake, Richard (1982). "Decadence, Decadentism and Decadent Romanticism in Italy: Toward a Theory of Decadence". Journal of Contemporary History. 17 (1): 69–92. doi:10.1177/002200948201700104. ISSN 0022-0094. JSTOR 260445.

- ^ Hoang, To Mai (2 January 2021). "Indirect Influence in Literature: The Case of Edgar Allan Poe, Charles Baudelaire, and Han Mac Tu". Comparative Literature: East & West. 5 (1): 29–45. doi:10.1080/25723618.2021.1886440. ISSN 2572-3618.

- ^ Hurst, Isobel (22 August 2019), Desmarais, Jane H.; Weir, David (eds.), "Nineteenth-Century Literary and Artistic Responses to Roman Decadence", Decadence and Literature, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 47–65, ISBN 978-1-108-42624-4, retrieved 24 July 2021.

- ^ Hoffleit, Gerald (2014), Landgraf, Diemo (ed.), "Progress and Decadence—Poststructuralism as Progressivism", Decadence in Literature and Intellectual Debate since 1945, New York: Palgrave Macmillan US, pp. 67–81, doi:10.1057/9781137431028_4, ISBN 978-1-137-43102-8, retrieved 24 July 2021.

- ^ Geoffrey Farrington (1994). The Dedalus Book of Roman Decadence: Emperors of Debauchery. Dedalus. ISBN 978-1-873982-16-7.

- ^ Patrick M. House (1996). The Psychology of Decadence: The Portrayal of Ancient Romans in Selected Works of Russian Literature of the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries. University of Wisconsin—Madison.

- ^ Toner, Jerry (2019), Weir, David; Desmarais, Jane (eds.), "Decadence in Ancient Rome", Decadence and Literature, Cambridge Critical Concepts, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 15–29, ISBN 978-1-108-42624-4, retrieved 24 July 2021.

- ^ a b c d Bristow, Joseph (19 June 2020). "Decadent Historicism". Volupté: 1–27 Pages, 4MB. doi:10.25602/GOLD.V.V3I1.1401.G1515.

- ^ a b c d Barrow, Rosemary (1997). "The Scent of Roses: Alma-Tadema and the Other Side of Rome". Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies. 42: 183–202. doi:10.1111/j.2041-5370.1998.tb00729.x. ISSN 0076-0730. JSTOR 43636546.

- ^ Kirkus UK review of Laqueur, Walter Weimar: A Cultural History, 1918–1933.

- ^ Lockerd, Martin (2023). "George Moore and Decadent Antinatalism". Christianity & Literature. 72 (2): 154–173. doi:10.1353/chy.2023.a904914. ISSN 2056-5666.

- ^ a b c d e Norman, Will (2009). "Lolita's 'Time Leaks' and transatlantic decadence". European Journal of American Culture. 28 (2): 185–204. doi:10.1386/ejac.28.2.185_1 – via EBSCOhost.

- ^ Parente-Capkova, Viola (1998). "Decadent New Woman?". NORA: Nordic Journal of Women's Studies. 6 (1): 6–20. doi:10.1080/08038749850167897 – via EBSCOhost.

- ^ a b Morse, Margaret (1977). "Decadence and Social Change: Arthur Schnitzler's Works as an Ongoing Process of Deconstruction". Modern Austrian Literature. 10 (2): 37–52 – via EBSCOhost.

- ^ a b c d e f Gare, Arran (2001). "Postmodernism as the Decadence of the Social Democratic State". Democracy and Nature. 7 (1): 77–99. doi:10.1080/10855660020028773. hdl:1959.3/5030.

- ^ Barzun, Jacques: From Dawn to Decadence: 500 Years of Western Cultural Life. HarperCollins, New York 2000.

- ^ Douthat, Ross (7 February 2020). "The Age of Decadence". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ Molitorisz, Sacha (2 December 2011). "Society is past its use by date". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- ^ Decadence: The Theory of Decline or the Decline of Theory? (Part I). Aufheben. Summer 1993.

- ^ Mora, José Ferrater (1956). Ortega y Gasset: an outline of his philosophy. Bowes & Bowes. p. 18.

- ^ Marx, Karl (1859). A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy. Progress Publishers.

Further reading

[edit]- Richard Gilman, Decadence: The Strange Life of an Epithet (1979). ISBN 0-374-13567-3

- Matei Calinescu, Five Faces of Modernity. ISBN 0-8223-0767-7

- Mario Praz, The Romantic Agony (1930). ISBN 0-19-281061-8

- Jacques Barzun, From Dawn to Decadence, (2000). ISBN 0-06-017586-9

- A. E. Carter, The Idea of Decadence in French Literature (1978). ISBN 0-8020-7078-7

- Michael Murray, Jacques Barzun: Portrait of a Mind (2011). ISBN 978-1-929490-41-7