Cuban War of Independence

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2020) |

| Cuban War of Independence | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Spanish–American War | |||||||

Lieutenant General Antonio Maceo's cavalry charge during the Battle of Ceja del Negro | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 53,774[1]: 308 | 196,000[1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

5,480 killed 3,437 dead from disease[2] |

9,413 killed[1] 53,313 dead from disease[1] | ||||||

| 300,000 Cuban civilians dead[3][4][1] | |||||||

| History of Cuba |

|---|

|

| Governorate of Cuba (1511–1519) |

|

|

| Viceroyalty of New Spain (1535–1821) |

|

|

| Captaincy General of Cuba (1607–1898) |

|

|

| US Military Government (1898–1902) |

|

|

| Republic of Cuba (1902–1959) |

|

|

| Republic of Cuba (1959–) |

|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

|

|

The Cuban War of Independence (Spanish: Guerra de Independencia cubana), also known in Cuba as the Necessary War (Spanish: Guerra Necesaria),[5] fought from 1895 to 1898, was the last of three liberation wars that Cuba fought against Spain, the other two being the Ten Years' War (1868–1878)[6] and the Little War (1879–1880). The final three months of the conflict escalated to become the Spanish–American War, with United States forces being deployed in Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippine Islands against Spain. Historians disagree as to the extent that United States officials were motivated to intervene for humanitarian reasons but agree that yellow journalism exaggerated atrocities attributed to Spanish forces against Cuban civilians.

Background

[edit]During the years 1879–1888 of the so-called "Rewarding Truce", lasting for 17 years from the end of the Ten Years' War in 1878, there were fundamental social changes in Cuban society. Cuba had maintained slavery and was still under colonial control while most Latin American countries were gaining independence throughout the nineteenth century. The island received economic benefits from keeping their connections with the Spanish because of their supply of sugar. Additionally, the white upper-class minority in Cuba had concerns that the island would follow Haiti's footsteps after their revolution, which caused them to maintain their support for Spanish rule.[7] With the abolition of slavery in October 1886, freedmen joined the ranks of farmers and the urban working class. The economy could no longer sustain itself with the shift and changes; therefore, many wealthy Cubans lost their property and joined the urban middle class. The number of sugar mills dropped and efficiency increased: only companies, and the most powerful plantation owners, remained in business followed by the Central Board of Artisans in 1879, and many more across the island.[8]

Jose Marti was a significant figure in the Cuban War of Independence and has a legacy that is still prominent to this day. After his second deportation to Spain in 1878, José Martí moved to the United States in 1881. There he mobilized the support of the Cuban exile community, especially in Ybor City (Tampa area) and Key West, Florida. Cuba Libre became a popular movement in these areas, especially in Ybor City, where nearly every facet of society supported this cause.[9]

His goal was revolution to achieve independence from Spain. Martí lobbied against the U.S. annexation of Cuba, which was desired by some politicians in both the U.S. and Cuba. His political orientation was more democratic than it was socialist, and these beliefs shaped the fight for Cuban freedom. However, the changes that Marti pushed for never occurred in Cuba because the Americans gained a powerful position over the island after the revolution.[10]

After deliberations with patriotic clubs across the United States, the Antilles and Latin America, "El Partido Revolucionario Cubano" (The Cuban Revolutionary Party) was in a state of pendency and was affected by a growing fear that the U.S. government would try to annex Cuba before the revolution could liberate the island from Spain.[11] Marti contributed to the creation of the party, which was based on his nationalist views, and he empowered the Cuban people with this party. The party also helped him patch up relations with other significant revolutionary leaders, such as Maximmo Gomez and Antonio Maceo.[10] Additionally, a new trend of aggressive U.S. "influence" was expressed by Secretary of State James G. Blaine's suggestion that all of Central and South America would someday fall to the U.S.:

"That rich island", Blaine wrote on 1 December 1881, "the key to the Gulf of Mexico, is, though in the hands of Spain, a part of the American commercial system ... If ever ceasing to be Spanish, Cuba must necessarily become American and not fall under any other European domination".[12] Because the US also had economic interests in Cuba, he also once stated that "our great demand is expansion; I mean expansion of trade with countries where we can find profitable exchanges."[13]

War

[edit]

On December 25, 1894, three ships – the Lagonda, the Almadis and the Baracoa – set sail for Cuba from Fernandina Beach, Florida, loaded with soldiers and weapons.[14] Two of the ships were seized by American authorities in early January, but the proceedings went ahead. Marti himself did not leave for Montecristi until January 31; it was on this trip that he would meet with General Maximo Gomez to finalize another invasion plan of Cuba.[15]

The insurrection began on February 24, 1895, with uprisings all across the island.[10] Marti and Gomez had planned a well-organized uprising that would work to eventually remove Spain from the island nation, though progress would be slow and cost many lives.[16] Word of the beginning of the revolution reached Marti and Gomez by the end of February.[15]

The war was the most prominent in Oriente, located in eastern Cuba. Since the eastern portion of Cuba was poorer, the Cubans were more motivated to fight there.[10] In Oriente, the most important skirmishes took place in Santiago, Guantánamo, Jiguaní, El Cobre, El Caney, and Alto Songo. Maceo focused on the war in Santiago, where he was highly successful in defeating the Spanish. Gomez was able to dominate the Spanish in the west in places such as Puerto Principe and Altagracia.[10] The uprisings in the central part of the island, such as Ibarra, Jagüey Grande, and Aguada, suffered from poor coordination and failed; the leaders were captured, deported or executed. In the province of Havana, the insurrection was discovered before it began, and its leaders were detained. The insurgents further west in Pinar del Río were ordered by rebel leaders to wait. On March 25 Martí presented the Manifesto of Montecristi, which outlined the policy for Cuba's war of independence:[15]

- The war was to be waged by blacks and whites alike;

- Participation of all blacks was crucial for victory;

- Spaniards who did not object to the war effort should be spared,

- Private rural properties should not be damaged; and

- The revolution should bring new economic life to Cuba.

During the war, around 40 percent of military officers were men of color. Black people were significant players in the war and had the ability to consolidate power in a way they were never able to before. Antonio Maceo was an example of a mulatto who gained a huge following throughout Cuba because of his military prowess. Antiracism was an important theme throughout the war, which starkly contrasted the views many Americans had about Black people in the United States.[7] Marti had compiled an essay titled Mi Raza, which stated that the idea of race was a social construct, which impacted his beliefs throughout the war.[17]

On April 1 and 11, 1895, the main rebel leaders landed on two expeditions in Oriente: Major General Antonio Maceo along with 22 members near Baracoa, and José Martí, Máximo Gómez and 4 other members in Playitas.[10] Spanish forces in Cuba numbered about 80,000, of which 20,000 were regular troops and 60,000 were Spanish and Cuban volunteer militia. The latter were a locally enlisted force that took care of most of the "guard and police" duties on the island. Wealthy landowners would "volunteer" some of their slaves to serve in this force, which was under local control as militia and not under official military command. By December, Spain had sent 98,412 regular troops to the island, and the colonial government increased the Volunteer Corps to 63,000 men. By the end of 1897, there were 240,000 regulars and 60,000 irregulars on the island. The revolutionaries were far outnumbered.

The rebels were often called mambises. The origin of this term is disputed. Some suggest it may have originated in the name of officer Juan Ethninius Mamby who led rebels in the Dominican fight for independence in 1844. Others, such as Cuban anthropologist Fernando Ortiz, posit it has Bantu origins, particularly from Kikongo[18] from the word 'mbi', which carried negative connotations including 'outlaw'. In any case, the word appears to have first been used as an insult or slur, which the Cuban rebels adopted with pride.

From the start of the uprising, the Mambises were hampered by the lack of weapons. Possession of weapons by individuals was forbidden after the Ten Years' War. They compensated by using guerrilla fighting, based on quick raids, the element of surprise, mounting their forces on fast horses, and using machetes against regular troops on the march. They acquired most of their weapons and ammunition in raids on the Spaniards. Between June 11, 1895, and November 30, 1897, of 60 attempts to bring weapons and supplies to the rebels from outside the country, only one succeeded. Twenty-eight ships were intercepted within U.S. territory; five were intercepted at sea by the U.S. Navy, and four by the Spanish Navy; two were wrecked; one was driven back to port by storm; the fate of another is unknown.

Martí was killed soon after landing on May 19, 1895, at Dos Rios, but Máximo Gomez and Antonio Maceo fought on, taking the war to all parts of Oriente.[10] By the end of June, all of Camagüey was at war. Based on new research in Cuban sources, historian John Lawrence Tone showed that Gomez and Maceo were the first to force the civilian forces to choose sides. "Either they relocated to the east side of the islands, where the Cubans controlled the mountainous terrain, or they would be accused of supporting the Spanish and be subject to immediate trial and execution."[19] Continuing west, they were joined by 1868 war veterans, such as Polish internationalist General Carlos Roloff and Serafín Sánchez in Las Villas, who brought weapons, men and experience to the revolutionaries' arsenal.

In mid-September, representatives of the five Liberation Army Corps assembled in Jimaguayú, Camagüey to approve the "Jimaguayú Constitution". They established a central government, which grouped the executive and legislative powers into one entity named "Government Council", headed by Salvador Cisneros and Bartolomé Masó. After some time of consolidation in the three eastern provinces, the liberation armies headed for Camagüey and then Matanzas, outmaneuvering and deceiving the Spanish Army several times. They defeated Spanish Gen. Arsenio Martínez-Campos y Antón, who had gained victory in the Ten-Year War, and killed his most trusted general at Peralejo.

Campos tried the strategy he had used in the Ten Years' War, constructing a broad belt across the island, called the trocha, about 80 km long and 200 m wide. This defense line was to confine rebel activities to the eastern provinces. The belt was developed along a railroad from Jucaro in the south to Morón in the north. Campos built fortifications along this railroad at various points, and at intervals, 12 meters of posts and 400 meters of barbed wire. In addition, booby traps were placed at locations most likely to be attacked.

The rebels believed they had to take the war to the western provinces of Matanzas, Havana and Pinar del Rio, which contained the island's government and wealth. The Ten-Year War had failed because it was confined to the eastern provinces. The revolutionaries mounted a cavalry campaign that overcame the trochas and invaded every province. Surrounding all larger cities and well-fortified towns, they arrived at the westernmost tip of the island on January 22, 1896, exactly three months after the invasion near Baraguá.

Campos was replaced by Gen. Valeriano Weyler.[10] He reacted to the rebels' successes by introducing terror: periodic executions, mass exile of residents, forced concentration of residents in certain cities or areas (policy of reconcentration), and destruction of farms and crops. Weyler's terror reached its height on October 21, 1896, when he ordered all countryside residents and their livestock to gather within eight days in various fortified areas and towns occupied by his troops. Anyone who did not report to the designated security zones was considered a rebel and could be killed.[20]

Hundreds of thousands of people had to leave their homes and were subjected to appalling and inhumane conditions in the crowded towns and cities. Using a variety of sources, Tone estimates that 155,000 to 170,000 civilians died, nearly 10% of the population.[19]

Around this time, Spain also had to fight a growing Philippines independence movement. These two wars burdened Spain's economy. In 1896, Spain turned down secret United States offers to buy Cuba.

Maceo was killed December 7, 1896, in Havana province while returning from the west.[10] The major obstacle to Cuban success was weapons supply. Although weapons and funding were sent by Cuban exiles and supporters in the United States, the supply violated U.S. laws. Of 71 supply missions, only 27 got through; 5 were stopped by the Spanish, and 33 by the U.S. Coast Guard.

In 1897, the liberation army maintained a privileged position in Camagüey and Oriente, where the Spanish controlled only a few cities. Spanish Liberal leader Práxedes Mateo Sagasta admitted in May 1897: "After having sent 200,000 men and shed so much blood, we don't own more land on the island than what our soldiers are stepping on".[21] The rebel force of 3,000 defeated the Spanish in various encounters, such as the La Reforma Campaign, and forcing the surrender on August 30 of Las Tunas which had been guarded by over 1,000 well-armed and well-supplied men.

As stipulated at the Jimaguayü Assembly two years earlier, a second Constituent Assembly met in La Yaya, Camagüey, on October 10, 1897. The newly adopted constitution provided that military command was to be subordinated to civilian rule. The government was confirmed, naming Bartolomé Masó President and Domingo Méndez Capote Vice President.

As a result of the assassination attempt on Prime Minister Antonio Cánovas del Castillo on 8 August 1897 and due to media criticism, the Spanish government decided to change its policy towards Cuba and dismiss General Valeriano Weyler from his position as governor of the island. Ramón Blanco - a strong opponent of the reconcentration policy - took over the function at the end of 1897.[20]

Madrit decided also to drew up a colonial constitution for Cuba and Puerto Rico, and installed a new government in Havana. But with half the country out of its control and the other half in arms, the colonial government was powerless and these changes were rejected by the rebels.

Maine incident

[edit]

The Cuban struggle for independence had captured the American imagination for years. Some newspapers had agitated for U.S. intervention, especially because of its large financial investment, and featured sensational stories of Spanish atrocities against the native Cuban population, which were exaggerated for propaganda.

Such coverage continued after Spain had replaced Weyler and changed its policies. American public opinion was very much in favor of intervening on behalf of the Cubans.[22]

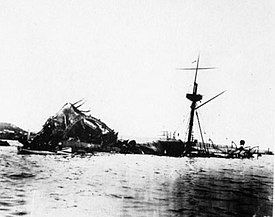

In January 1898, a riot by Cuban Spanish loyalists against the new autonomous government broke out in Havana. They destroyed the printing presses of four local newspapers that had published articles critical of Spanish Army atrocities. The U.S. Consul-General cabled Washington with fears for the lives of Americans living in Havana. In response, the battleship USS Maine was sent to Havana in the last week of January. On February 15, 1898, Maine was rocked by an explosion, killing 260[23] of the crew and sinking the ship in the harbor. The ship was attacked on the front side, which contributed to the high death toll.[24] At the time, a military Board of Investigations decided that Maine had exploded due to the detonation of a mine underneath the hull. However, later investigations decided that it was likely something inside the ship, though the cause of the explosion has not been clearly established to this day.[25]

In an attempt to appease the U.S., the colonial government took two steps that had been demanded by President William McKinley: it ended forced relocation of residents from their homes and offered negotiations with the independence fighters. But the truce was rejected by the rebels.

Spanish–American War

[edit]

The sinking of the Maine sparked a wave of public indignation in the United States. Newspaper owners such as William R. Hearst leaped to the conclusion that Spanish officials in Cuba were to blame, and they widely publicized the conspiracy. To further blame the Spanish and back Cuban efforts against them, he mentioned the story of Evangelina Cisneros, who was thrown in prison for denying sexual favors with a Spanish officer. This caught the attention of many American women, who further strengthened public opinion in the United States.[26] Realistically, Spain could have had no interest in drawing the U.S. into the conflict.[27] Yellow journalism fueled American anger by publishing "atrocities" committed by Spain in Cuba. Frederic Remington, hired by Hearst to illustrate for his newspaper, informed Hearst that conditions in Cuba were not bad enough to warrant hostilities. Hearst, allegedly replied, "You furnish the pictures and I'll furnish the war".[28] President McKinley, Speaker of the House Thomas Brackett Reed, and the business community opposed the growing public demand for war, which was lashed to fury by the yellow journalism. Even Theodore Roosevelt spoke out against the Spanish, responding quickly after the incident.[24] The American cry of the hour became, Remember the Maine, To Hell with Spain!

The decisive event was probably the speech of Senator Redfield Proctor, delivered on March 17, 1898, analyzing the situation and concluding that war was the only answer. The business and religious communities switched sides, leaving McKinley and Reed almost alone in their opposition to war.[29][30] "Faced with a revved up, war-ready population, and all the editorial encouragement the two competitors could muster, the United States jumped at the opportunity to get involved and showcase its new steam-powered Navy".[12] Had he not adhered to the coercion of the general public, McKinley feared that non-interference would ruin his political reputation.[24]

On April 11, McKinley asked Congress for authority to send American troops to Cuba to end the civil war there. On April 19, Congress passed joint resolutions (by a vote of 311 to 6 in the House and 42 to 35 in the Senate) supporting Cuban independence and disclaiming any intention to annex Cuba, demanding Spanish withdrawal, and authorizing the president to use as much military force as he thought necessary to help Cuban patriots gain independence from Spain. This was adopted by resolution of Congress and included the Teller Amendment, named after Colorado Senator Henry Moore Teller, which passed unanimously, stipulating that "the island of Cuba is, and by right should be, free and independent".[27] The amendment disclaimed any intention by U.S. to have jurisdiction or control over Cuba for other than pacification reasons, and confirmed that the armed forces would be removed at the conclusion of the war. The amendment, pushed through at the last minute by anti-imperialists in the Senate, made no mention of the Philippines, Guam, or Puerto Rico. Congress declared war on April 25.[31]

The arguments that circulated between Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst perpetuated the hatred many Americans had for the Spanish.[24] Joseph E. Wisan wrote in an essay titled "The Cuban Crisis As Reflected In The New York Press", published in "American Imperialism" in 1898: "In the opinion of the writer, the Spanish–American War would not have occurred had not the appearance of Hearst in New York journalism precipitated a bitter battle for newspaper circulation." It has also been argued that the main reason the United States entered the war was its failed attempt to purchase Cuba from Spain.[12]

Hostilities started hours after the declaration of war when a contingent of U.S. Navy ships under Admiral William T. Sampson blockaded several Cuban ports. The Americans decided to invade Cuba and to start in Oriente, where the Cubans had almost absolute control. They cooperated by establishing a beachhead and protecting the U.S. landing in Daiquiri. The first U.S. objective was to capture the city of Santiago in order to destroy Linares' army and Cervera's fleet. To reach Santiago, the Americans had to pass through concentrated Spanish defences in the San Juan Hills and a small town in El Caney. Between June 22 and 24, 1898, the Americans landed under General William R. Shafter at Daiquirí and Siboney, east of Santiago, and established a base.

The port of Santiago became the main target of naval operations. The U.S. fleet attacking Santiago needed shelter from the summer hurricane season, thus nearby Guantánamo Bay, with its excellent harbor, was chosen for this purpose and attacked on June 6 (1898 invasion of Guantánamo Bay). The Battle of Santiago de Cuba on July 3, 1898, was the largest naval engagement during the Spanish–American War, resulting in the destruction of the Spanish Caribbean Squadron (Flota de Ultramar).

Resistance in Santiago consolidated around Fort Canosa,[32] All the while, major battles between Spaniards and Americans took place at Las Guasimas on June 24, El Caney and San Juan Hill on July 1, 1898, outside Santiago.[33] after which the American advance ground to a halt. Spanish troops successfully defended Fort Canosa, allowing them to stabilize their line and bar the entry to Santiago. The Americans and Cubans forcibly began a bloody, strangling siege of the city[34] which eventually surrendered on July 16, after the defeat of the Spanish Caribbean Squadron. Thus, Oriente was under control of Americans, but U.S. General Nelson A. Miles would not allow Cuban troops to enter Santiago, claiming that he wanted to prevent clashes between Cubans and Spaniards. Thus, Cuban General Calixto García, head of the Mambi forces in the Eastern department, ordered his troops to hold their respective areas. He resigned over being excluded from entering Santiago, writing a letter of protest to General Shafter.[27]

Peace

[edit]After losing the Philippines and Puerto Rico, which had also been invaded by the United States, and with no hope of holding on to Cuba, Spain opted for peace on July 17, 1898.[35] On August 12, the United States and Spain signed a protocol of Peace, in which Spain agreed to relinquish all claims of sovereignty over Cuba.[36] On December 10, 1898, the United States and Spain signed the Treaty of Paris, which demanded the formal recognition of Cuban independence on part of Spain.[37]

Although the Cubans had participated in the liberation efforts, the United States prevented Cuba from participating in the Paris peace talks and the signing of the treaty. The treaty did not set a designated time limit for U.S. occupation, and the Isle of Pines was excluded from Cuba.[38] The treaty officially granted Cuban independence, but U.S. General William R. Shafter refused to allow Cuban General Calixto García and his rebel forces to participate in the surrender ceremonies in Santiago de Cuba.[39]

Legacy

[edit]Fidel Castro sought to frame the 26th of July Movement as a direct continuation of the anti-colonial struggle of the Ten Years' War and the War of Independence.[40]: 22–23

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Clodfelter (2017). Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492–2015.

- ^ Clodfelter, Micheal, Warfare and Armed Conflict: A Statistical Reference to Casualty and Other Figures, 1618–1991

- ^ Sheina, Robert L., Latin America's Wars: The Age of the Caudillo, 1791–1899 (2003)

- ^ COWP: Correlates of War Project, University of Michigan

- ^ "24 de febrero de 1895: La guerra necesaria de José Martí". Prensa Latina. February 24, 2023. Archived from the original on February 24, 2023.

- ^ "The Spanish-American War - The World of 1898: The Spanish-American War (Hispanic Division, Library of Congress)". www.loc.gov. Retrieved February 10, 2023.

- ^ a b Ferrer, Ada (1999). "Cuba, 1898: Rethinking Race, Nation, and Empire". Radical History Review (73): 23–25.

- ^ Navarro (1998). History of Cuba. Havana. pp. 55–57

- ^ Mormino, Gary R. (1998). "Tampa's Splendid Little War: Local History and the Cuban War of Independence". OAH Magazine of History. 12 (3): 37–42. ISSN 0882-228X.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Tone, John Lawrence (2006). War and Genocide in Cuba: 1895-1898. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- ^ Foner, Philip (1972) The Spanish–Cuban–American War and the Birth of American Imperialism quoted in: [1], History of Cuba

- ^ a b c "Spanish-Cuban-American War - History of Cuba". www.historyofcuba.com.

- ^ Rodríguez, Raúl; Targ, Harry (2015). "US Foreign Policy towards Cuba: Historical Roots, Traditional Explanations and Alternative Perspectives". International Journal of Cuban Studies. 7 (1): 16–37. doi:10.13169/intejcubastud.7.1.0016. ISSN 1756-3461.

- ^ Villafana, Frank (2011). Expansionism: Its Effects on Cuba's Independence (1 ed.). Routledge. p. 117. ISBN 9781138509931.

- ^ a b c Gray, Richard (1962). Jose Marti, Cuban Patriot. University of Florida Press. p. 25.

- ^ Hudson, Rex (2002). Cuba: A Country Study. Department of the Army. p. 29.

- ^ Fountain, Anne (2014). Jose Marti, the United States, and Race. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

- ^ "Versiones del origen de mambí". www.juventudrebelde.cu (in Spanish). Retrieved March 7, 2022.

- ^ a b Krohn, Jonathan. (May 2008) Review: "Caught in the Middle" John Lawrence Tone. War and Genocide in Cuba 1895–1898 (2006), H-Net, accessed December 26, 2014

- ^ a b Chustecki, Jakub (2023). "Colonial concentration camps in Cuba and South Africa. Characteristics and significance for the evolution of the idea". Świat Idei i Polityki. 22 (2): 143–144. doi:10.34767/SIIP.2023.02.09. ISSN 1643-8442.

- ^ Navarro, José Cantón 1998. History of Cuba. Havana. p69

- ^ PBS, Crucible of Empire: The Spanish–American War, pbs.org, retrieved December 15, 2007

- ^ "The Destruction of USS Maine". Naval History and Heritage Command. Archived from the original on December 18, 2020. Retrieved September 8, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Pérez, Louis A. (August 1, 1989). "The Meaning of the Maine: Causation and the Historiography of the Spanish-American War". Pacific Historical Review. 58 (3): 293–322. doi:10.2307/3640268. ISSN 0030-8684. JSTOR 3640268.

- ^ "Uss Maine". Archived from the original on August 18, 2007. Retrieved August 20, 2007.

- ^ Lowry, Elizabeth (2013). "The Flower of Cuba: Rhetoric, Representation, and Circulation at the Outbreak of the Spanish-American War". Rhetoric Review. 32 (2): 174–190. ISSN 0735-0198.

- ^ W. Joseph Campbell (Summer 2000). "Not likely sent: The Remington–Hearst "telegrams"". Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly.

- ^ Offner 1992 pp. 131–35

- ^ Davis, Michelle Bray & Quimby, Rollin W. (1969), "Senator Proctor's Cuban Speech: Speculations on a Cause of the Spanish–American War", Quarterly Journal of Speech, 55 (2): 131–41, doi:10.1080/00335636909382938, ISSN 0033-5630.

- ^ "Declaration of War against Spain, April 25, 1898". U.S. Capitol Visitor Center, Legislative Highlights; 55th Congress. Archived from the original on June 30, 2022. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ Daley, L. (2000). "El Fortin Canosa en la Cuba del 1898". In B.E. Aguirre; E. Espina (eds.). Los Ultimos Dias del Comienzo. Ensayos sobre la Guerra Hispano-Cubana-Estadounidense. Santiago de Chile: RiL Editores. pp. 161–71.

- ^ The Battles at El Caney and San Juan Hills Archived July 14, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, HomeOfHeroes.com.

- ^ Daley 2000, pp. 161–71

- ^ The Spanish–American War Centennial Website!, spanamwar.com, retrieved November 2, 2007

- ^ Protocol of Peace Embodying the Terms of a Basis for the Establishment of Peace Between the Two Countries, Washington, D.C., August 12, 1898, retrieved October 30, 2007

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Treaty of peace between the United States and Spain, The Avalon project at Yale law School, December 10, 1898, archived from the original on November 6, 2007, retrieved October 30, 2007

- ^ Navarro, José Cantón: History of Cuba, Havana, Cuba, 1998, p. 77

- ^ "This Day in Cuban History - July 16, 1898. The Surrender of Santiago de Cuba". Cuban Studies Institute. July 16, 2018. Retrieved June 28, 2022.

- ^ Cederlöf, Gustav (2023). The Low-Carbon Contradiction: Energy Transition, Geopolitics, and the Infrastructural State in Cuba. Critical environments: nature, science, and politics. Oakland, California: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-39313-4.

Further reading

[edit]- Kagan, Robert, (2006) Dangerous Nation (New York: Alfred A. Knopf), pp. 357–416

- Krohn, Jonathan. (May 2008) Review: "Caught in the Middle" John Lawrence Tone. War and Genocide in Cuba 1895–1898 (2006) Review of Tone, John Lawrence, War and Genocide in Cuba 1895-1898, H-Net, May 2008

- McCartney, Paul T. (2006) Power and Progress: American National Identity, the War of 1898, and the Rise of American Imperialism (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press), 87–142

- Rice, Donald Tunnicliff. Cast in Deathless Bronze: Andrew Rowan, the Spanish–American War, and the Origins of American Empire. Morgantown WV: West Virginia University Press, 2016.

- Silbey, David J. (2007) A War of Frontier and Empire: The Philippine–American War, 1899–1902 (New York: Hill and Wang), pp. 31–34.

- Tone, John Lawrence. (2006) War and Genocide in Cuba 1895–1898, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina excerpt and text search

- Trask, David F. The War with Spain in 1898 (1996) ch 1 excerpt and text search

- Cuban War of Independence

- Conflicts in 1895

- Conflicts in 1896

- Conflicts in 1897

- Conflicts in 1898

- Spanish colonial period of Cuba

- 19th century in Cuba

- Wars of independence

- Anti-imperialism in North America

- Military history of the Caribbean

- Military history of Cuba

- Spanish American wars of independence

- Rebellions against the Spanish Empire

- Wars involving Cuba

- Wars involving Spain

- 19th-century rebellions

- 19th-century revolutions

- 1895 in Cuba

- 1896 in Cuba

- 1897 in Cuba

- 1898 in Cuba

- Spanish–American War