Bloomingdale (Washington, D.C.)

Bloomingdale, Washington, D.C. | |

|---|---|

Victorian-style rowhouses in Bloomingdale. | |

Bloomingdale in the District of Columbia | |

| Country | United States |

| District | Washington, D.C. |

| Ward | Ward 5 |

| Advisory Neighborhood Commission | ANC 5E |

| Government | |

| • Councilmember | Zachary Parker (Ward 5) |

| Area | |

• Total | 0.247 sq mi (0.64 km2) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 6,258 |

| • Density | 25,153/sq mi (9,712/km2) |

| ZIP Code | 20001 |

| Area code | 202 |

Bloomingdale Historic District | |

| Location | Bounded by Florida Ave., Channing, Bryant, North Capitol & 2nd Sts. |

| NRHP reference No. | 100003129[1] |

| Added to NRHP | November 26, 2018 |

Bloomingdale is a neighborhood in the Northwest quadrant of Washington, D.C., less than two miles (3 km) north of the United States Capitol building. It is a primarily residential neighborhood, with a small commercial center near the intersection of Rhode Island Avenue and First Street NW featuring bars, restaurants, and food markets.

Most of Bloomingdale's houses are Victorian-style rowhouses built around 1900 as single-family homes. Today, they remain primarily single-family residences, with some recently converted to two-unit condominiums.

Geography

[edit]Bloomingdale is bounded to the north by Channing Street NW, to the east by North Capitol Street, to the south by Florida Avenue NW, and to the west by Second Street NW.

The neighborhoods bordering Bloomingdale are LeDroit Park to the west, Shaw to the southwest, Truxton Circle to the south, Eckington to the east, and Stronghold to the northeast. To the north sit the McMillan Sand Filtration Site and the McMillan Reservoir.

The neighborhood is a low-lying area, at the foot of hills that extend to the north and east. Its topography is also shaped by the now-buried Tiber Creek, one branch of which generally followed what is now Flagler Place NW.

Because of its low-lying topography, flooding periodically occurred in parts of the neighborhood during particularly strong rainstorms. In summer 2012, the stormwater drainage system was overwhelmed multiple times by particularly strong storms, flooding vehicles near the topographic basin at T Street NW and Rhode Island Avenue NW and causing sewer backflow to enter some basements, many of which were rental apartments.[2] Since then, DC Water has undertaken a large-scale tunneling project designed to divert and contain stormwater.[3]

Government

[edit]Bloomingdale is in the southwestern part of Ward 5, currently represented on the City Council by Councilmember Zachary Parker.[4] Bloomingdale is a part of Advisory Neighborhood Commission 5E, with commissioners Karla Lewis, Fred Carver, Huma Imtiaz and Kevin Rapp representing sections of the neighborhood.[5]

History

[edit]The present-day neighborhood of Bloomingdale originated from several large estates. Located just outside the original boundary of the City of Washington as designed by Pierre L’Enfant in 1792 and in the former County of Washington, the neighborhood known today as Bloomingdale began to develop its residential character in the late 1880s, shortly after the County of Washington was absorbed by the City of Washington and just over a century after L'Enfant's plan was developed.

1792–1870s: farms and estates

[edit]The lands that comprise Bloomingdale first began as large estates and orchards. Boundary Street, today Florida Avenue, was the dividing line between paved, planned streets (to the south), laid out in the original L'Enfant Plan, and rural country (to the north of Boundary), where landowners maintained orchards, large country estates and, later, a mixture of commercial properties.

In 1823, George Beale and his wife Emily Truxton Beale bought a 10-acre (40,000 m2) parcel of land north of the Capitol, along the City boundary, for $600.00 from William Bradley.[6] They named it the "Bloomingdale Estate," and it grew to 50 acres (200,000 m2).

As late as the 1870s, the land where Bloomingdale now sits was largely a collection of undeveloped private estates and farming properties, most prominently those of the Beales and of the Moores.[7]

1880s onward: residential development

[edit]

Following Emily Truxton Beale's death in 1885, her heirs began to sell large tracts of the estate to developers. The old Bloomingdale estate rapidly changed into the modern neighborhood configuration as developers and land speculators transformed the undeveloped lands for denser residential development, between the established residential LeDroit Park and Eckington neighborhoods. By 1887, city planners had proposed extending the city's paved street grid into Bloomingdale.[8]

In 1891, the 45-acre (180,000 m2) Moore farm, north and west of the former Beale estate and representing some of the last undeveloped property in the area, was sold to private developers.[9] It was incorporated into the already-underway Bloomingdale neighborhood.

By 1892, the reconfiguration of Bloomingdale was underway, as large estates were consolidated and reconfigured into the predecessor to the modern neighborhood,[10] with further development by 1894.[11] During this time, roads corresponding to the grid system of Washington's streets were improved, curbed, and paved. Streams and creeks were buried or re-directed—most notably the Tiber Creek, many of which had been buried south of Bloomingdale in the original City of Washington. One section of the Tiber Creek in Bloomingdale ran along what is now Flagler Place.[12]

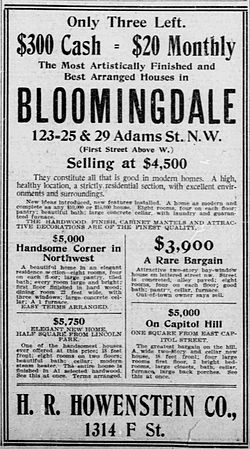

Construction on some of the earliest homes was completed between 1892 and 1900.[citation needed] In the early 1900s, the remainder of the surrounding blocks had been built in a speculative nature by such developers as Harry Wardman, Francis Blundon, and S. H. Meyers in the following decade. The neighborhood website contains a list of Bloomingdale's Wardman built homes. Many of Wardman's first homes incorporate elements of Richardson Romanesque architecture (a sub-category of Victorian).[13] This can be seen in the ornate floral and vine-like stone carving around doors and windows of many Bloomingdale homes. His later homes, like those on Adams and Bryant Streets, are in an architectural style for which he is most prominently known, brick homes that incorporate a deeper setback from the street and large covered front porch. Blundon built several homes along 1st Street including 100 W Street, NW, which he occupied with his family.

Development continued and, in 1904, the neighborhood's first school, the Nathaniel Parker Gage School, was built on the 2000 block of 2nd Street. (The school has been converted to private condominiums.) By 1909, the old estates had been sold and divided, the Tiber Creek had been buried, and the neighborhood street layout had been fully developed into its present form.[14][15]

Many homes in the northern section of Bloomingdale retain carriage houses in the block interiors. Some have been converted to private residences.

2000–present

[edit]

Like many D.C. neighborhoods since the early 2000s, Bloomingdale has undergone substantial gentrification, with the neighborhood's once-numerous vacant properties being repurposed, sharp rises in property values, and rapidly shifting demographics. The population is nearly evenly split between White residents, many of whom have moved to the neighborhood since the 2000s, and African American residents, who have historically constituted a majority in the community.

During this period of rapid change, new businesses have opened in the neighborhood, primarily restaurants, bars, and food markets. Every summer, the Bloomingdale Farmers' Market operates on Sundays on R St between Florida Ave and 1st Street, N.W.

On May 22, 2010, the city officially dedicated a new street, Bloomingdale Court, N.W., the name given by local resident and novelist Frederick Louis Richardson for the alley system between the 100 block of U and V Streets, N.W., and the 2000 block of 1st Street and Flagler Place, N.W.

On July 27, 2018, the D.C. Historic Preservation Review Board voted to designate Bloomingdale a historic district.[16] It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on November 26 of the same year.[1]

The neighborhood has several active neighborhood groups and associations, including the Bloomingdale Civic Association.

Demographics

[edit]According to the Census Bureau's 2020 American Community Survey, the population of Bloomingdale's two census tracts was estimated to be 6,258 made up of about 31.5% Black or African American alone, about 51.5% White alone, about 7.6% Hispanic or Latino, and about 4.4% Asian alone.[17]

Crispus Attucks Park

[edit]

Bloomingdale has its own community-managed and community-owned greenspace, Crispus Attucks Park. The acre-and-a-quarter park, in the court bounded by First, U, V, and North Capitol streets NW, was previously the site of a warehouse built in 1910 and used as a telephone-switching station and cable yard for the Chesapeake & Potomac Telephone Company.[18]

Chesapeake & Potomac Telephone Company stopped using the property in 1974 and tried to sell it, but no one wanted to buy it,[18] largely because the only access was by way of an alley off of V Street NW.[19] In 1976, a neighborhood organization, V Street Block Club, approached the Chesapeake & Potomac Telephone Company to donate the property.[20][21][22] The neighborhood organization asked the Chesapeake & Potomac Telephone Company to use the warehouse to teach children to play music in the warehouse.[18] Chesapeake & Potomac Telephone Company said it would prefer to donate the property to the government of the District of Columbia, which would then donate the property to the neighborhood organization.[18] The District government declined the offer, because it did not have the funds to renovate the building,[19] and nothing happened for a few months.[18] In December 1976, Hyman Construction Company learned about the issue, and it agreed to renovate the warehouse; Chesapeake & Potomac Telephone Company agreed to donate the land and the warehouse to a newly incorporated neighborhood organization, then called NUV-1, an acronym for each street that surrounds the property.[18][19]

Hyman Construction Company paid its employees to renovate the warehouse, and employees of a few other construction companies donated their time as well.[18] National Capital United Presbytery donated $7,500, and architect Ward Bucher donated his time to create the plans.[18] Renovation began in July 1977, and the building officially opened as a neighborhood arts center on April 2, 1978.[18]

The neighborhood arts center offered photography, martial arts, and bicycle-repair classes, lectures, musical events, dances, and daycare.[23] In 1987, the District government reduced funding through the Recreation Department, and the six of the center's eight staff members were let go, significantly reducing the activities at the center.[23]

The neighborhood organization became the Crispus Attucks Development Corporation,[24][21] a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.[25] The park is named after Crispus Attucks, an African American who was killed in the Boston Massacre and is often regarded as the first person killed in the American Revolution. Crispus Attucks Park is privately owned and open to the public. It is maintained through charitable donations and volunteer labor coordinated by the Crispus Attucks Development Corporation.[26]

Notable residents and historic landmarks

[edit]

- Since 2018, the Bloomingdale neighborhood as a whole has been a designated historic district, with a period of significance from 1891 to 1948.[16]

- Samuel Gompers, the founder of the American Federation of Labor in 1886 (which later became the AFL–CIO), owned and lived in the house at 2122 1st Street, N.W. following its construction in 1900. The house was declared an individual landmark on the National Register of Historic Places in 1974.

- Chita Rivera, an accomplished singer, dancer, and entertainer on Broadway. Ms. Rivera lived with her parents (both federal government employees) on the 2100 block of Flagler Place, N.W. until the age of 15.

- The Barnett-Aden Gallery, formerly at 127 Randolph Place, N.W.,[27] was the first privately owned black gallery in the U.S. and one of Washington, D.C.’s principal art galleries when it opened in 1943. Founded by James V. Herring and Alonzo J. Aden, it was named ‘Barnett-Aden' to honor Aden’s mother’s family. While the owners of the gallery were African American, Barnett-Aden was not conceived as a "black gallery." It was one of the few art places in the city where artists representing different nationalities, races, and ethnicities were exhibited together.[28] The gallery's collection has since been sold and relocated.

- The house at 116 Bryant Street, N.W. was the subject of the Supreme Court case, Hurd v. Hodge.[29] The house was purchased by James M. Hodge and his wife, an African American couple, in violation of a racially restrictive covenant, which the Hodges challenged in court. This case was a companion to Shelley v. Kraemer, which found the enforcement of racial and religious covenants restricting the sale of certain homes to racial and religion minorities to be unconstitutional. Hurd v. Hodge clarified that this ruling applied to the District of Columbia.[30]

- The Nathaniel Parker Gage School on Second Street, N.W. was built as a school in 1904.[31] It is an historic structure, listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2008. The building now houses condominiums.

In popular culture

[edit]Although the series House of Cards was filmed in Baltimore, its opening credits sequence features several prominent shots of the Bloomingdale neighborhood along North Capitol Street, between R Street and T Street.[32]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "National Register of Historic Places Program: Weekly List". National Park Service. November 30, 2018. Retrieved 2018-11-30.

- ^ "Councilmember: Relief fund needed for victims of Sunday's flooding". wtop.com. 2 September 2012. Retrieved 2012-09-03.

- ^ "Bloomingdale and LeDroit Park: The Northeast Boundary Protection Program". dcwater.org. Archived from the original on 2014-02-28. Retrieved 2014-02-21.

- ^ "Ward 5 Councilmember Zachary Parker • Council of the District of Columbia". The Council of the District of Columbia. 2 January 2023. Retrieved 15 February 2023.

- ^ https://anc.dc.gov/page/advisory-neighborhood-commission-5e.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Why Is It Named Bloomingdale?". Ghosts of DC. 22 October 2012. Retrieved 2014-02-25.

- ^ "Atlas of fifteen miles around Washington (1879)". Library of Congress. Retrieved 4 May 2016.

- ^ "Map of Washington, D.C., and environs : with marginal numbers and measuring tape attachment for instantly locating points of interest within a radius of twenty miles from the Capitol / Library of Congress". loc.gov. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- ^ "1891: The Moore addition - updated". Bloomingdale History Project. Archived from the original on 2014-03-08.

- ^ "The altograph of Washington City, or, stranger's guide : Library of Congress". loc.gov. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- ^ "The vicinity of Washington, D.C., Library of Congress". loc.gov. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- ^ "Hidden Washington: Tiber Creek". Park View, D.C. 8 September 2011. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- ^ Scott, Pamela. "Residential Architecture of Washington, D.C., and Its Suburbs". loc.gov. Library of Congress. Retrieved August 17, 2016.

Last revised: 2005

- ^ "1907 Baist Map of LeDroit Park and Bloomingdale". Library of Congress. Retrieved 4 May 2016.

- ^ "1909: 'Homes of a Hundred Ideas'". The Bloomingdale History Project. August 2013. Archived from the original on 2014-12-23.

- ^ a b "Bloomingdale Historic District". D.C. Office of Planning. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 23 April 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Oman, Anne H. "Community Turns Warehouse Into Neighborhood Arts Center". The Washington Post. April 6, 1978. p. DC2.

- ^ a b c Von Eckardt, Wolf. "Pitching In on a New Park for the Arts: Neighbors Pitching In On a Park for the Arts". The Washington Post. April 8, 1978. p. C1.

- ^ Kyriakos, Marianne. "Bloomingdale's Oasis Rises From the Ashes: Partnership Created to Restore Beloved Crispus Attucks Park". The Washington Post. May 9, 1996. p. DC1.

- ^ a b "History". Crispus Attucks Development Corporation. Archived from the original Archived 2014-02-28 at archive.today on December 20, 2014.

- ^ Schwartzman, Paul (2012-05-21). "A feud over a D.C. park pits one man against his neighbors". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2020-05-06.

- ^ a b Armstrong, Jenice. "Center's Hard Times: Some Activists Seek New Leadership". The Washington Post. April 26, 1990. p. J1.

- ^ "Crispus Attucks Development[permanent dead link]". Department of Consumer and Regulatory Affairs. Government of the District of Columbia. Retrieved May 23, 2017.

- ^ "Crispus Attucks Development Corporation". Exempt Organizations Select Check. Internal Revenue Service. Retrieved May 23, 2017.

- ^ "Form 990-EZ: Short Form Return of Organization Exempt from Income Tax". Crispus Attucks Development Corporation. Guidestar. December 31, 2013.

- ^ "Art Exhibition Features Negro". New York Amsterdam News. October 21, 1944. p. 4B. ProQuest 226025593.

- ^ "BARNETT ADEN GALLERY, AFRICAN AMERICAN HERITAGE TRAIL". Cultural Tourism DC. Archived from the original on 2013-03-04. Retrieved 2014-02-26.

- ^ "Restrictive Writ Cases Argued Before U. S. Supreme Court: Seven Hours Allotted For Argumentation". Atlanta Daily World. January 15, 1948. p. 1. ProQuest 490846919.

- ^ "Hurd v. Hodge 334 U.S. 24 (1948)". FindLaw.

- ^ "Dedication of Gage School: Board of Education Completes Arrangements for Ceremony February 15". The Washington Post. February 9, 1905. p. 5. ProQuest 144625455.

- ^ Hennessey, Sean (3 February 2013). "House of Cards". Bloomingdale. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

External links

[edit]- Bloomingdale Neighborhood Blog and Listserv

- Why Is It Named Bloomingdale? — Ghosts of DC history blog

- If Walls Could Talk: Big Bear Cafe — history of the building that houses Big Bear Cafe