Epidural hematoma

| Epidural hematoma | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Extradural hematoma, epidural hemorrhage, epidural haematoma, epidural bleeding |

| |

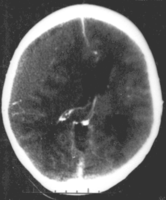

| Epidural hematoma as seen on a CT scan with overlying skull fracture. Note the biconvex shaped collection of blood. There is also bruising with bleeding on the opposite side of the brain. | |

| Specialty | Neurosurgery, Neurology |

| Symptoms | Headache, confusion, paralysis[1] |

| Usual onset | Rapid[2] |

| Causes | Head injury, bleeding disorder, blood vessel malformation[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Medical imaging (CT scan)[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Subdural hematoma, subarachnoid hemorrhage, traumatic brain injury,[1] transient ischemic attack seizure, intracranial abscess, brain tumor[3] |

| Treatment | Surgery (craniotomy, burr hole)[1] |

Epidural hematoma is when bleeding occurs between the tough outer membrane covering the brain (dura mater) and the skull.[4] When this condition occurs in the spinal canal, it is known as a spinal epidural hematoma.[4]

There may be loss of consciousness following a head injury, a brief regaining of consciousness, and then loss of consciousness again.[2] Other symptoms may include headache, confusion, vomiting, and an inability to move parts of the body.[1] Complications may include seizures.[1]

The cause is typically a head injury that results in a break of the temporal bone and bleeding from the middle meningeal artery.[4] Occasionally it can occur as a result of a bleeding disorder or blood vessel malformation.[1] Diagnosis is typically by a CT scan or MRI scan.[1]

Treatment is generally by urgent surgery in the form of a craniotomy or burr hole,[1] or (in the case of a spinal epidural hematoma) laminotomy with spinal decompression.

The condition occurs in one to four percent of head injuries.[1] Typically it occurs in young adults.[1] Males are more often affected than females.[1]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]Many people with epidural hematomas experience a lucid period immediately following the injury, with a delay before symptoms become evident.[5] Because of this initial period of lucidity, it has been called "Talk and Die" syndrome.[6] As blood accumulates, it starts to compress intracranial structures, which may impinge on the third cranial nerve, causing a fixed and dilated pupil on the side of the injury.[5] The eye will be positioned down and out due to unopposed innervation of the fourth and sixth cranial nerves.[citation needed]

Other symptoms include severe headache; weakness of the extremities on the opposite side from the lesion due to compression of the crossed pyramid pathways; and vision loss, also on the opposite side, due to compression of the posterior cerebral artery. In rare cases, small hematomas may be asymptomatic.[3]

If not treated promptly, epidural hematomas can cause tonsillar herniation, resulting in respiratory arrest. The trigeminal nerve may be involved late in the process as the pons is compressed, but this is not an important presentation, because the person may already be dead by the time it occurs.[7] In the case of epidural hematoma in the posterior cranial fossa, tonsillar herniation causes Cushing's triad: hypertension, bradycardia, and irregular breathing.[citation needed]

Causes

[edit]

The most common cause of intracranial epidural hematoma is head injury, although spontaneous hemorrhages have been known to occur. Epidural hematomas occur in about 10% of traumatic brain injuries, mostly due to car accidents, assaults, or falls.[3] They are often caused by acceleration-deceleration trauma and transverse forces.[8][9]

Epidural hematoma commonly results from a blow to the side (temporal bone) of the head. The pterion region, which overlies the middle meningeal artery, is relatively weak and prone to injury.[10] Only 20 to 30% of epidural hematomas occur outside the region of the temporal bone.[11] The brain may be injured by prominences on the inside of the skull as it scrapes past them. Epidural hematoma is usually found on the same side of the brain which was impacted by the blow, but on very rare occasions it can be due to a contrecoup injury.[12]

A "heat hematoma" is an epidural hematoma caused by severe thermal burn, causing contraction and exfoliation of the dura mater and exfoliate from the skull, in turn causing exudation of blood from the venous sinuses.[13] The hematoma can be seen on autopsy as brick red, or as radiolucent on CT scan, because of heat-induced coagulation of the hematoma.[13]

Pathophysiology

[edit]The break of the temporal bone causes bleeding from the middle meningeal artery, [4] hence epidural bleeding is often rapid as arteries are high-pressure flow. In 10% of cases, however, it comes from veins and can progress more slowly.[10] A venous hematoma may be acute (occurring within a day of the injury and appearing as a swirling mass of blood without a clot), subacute (occurring in 2–4 days and appearing solid), or chronic (occurring in 7–20 days and appearing mixed or lucent).[3]

In adults, the temporal region accounts for 75% of cases. In children, however, they occur with similar frequency in the occipital, frontal, and posterior fossa regions.[3] Epidural bleeds from arteries can grow until they reach their peak size 6–8 hours post-injury, spilling 25–75 cubic centimeters of blood into the intracranial space.[8] As the hematoma expands, it strips the dura from the inside of the skull, causing an intense headache. It also increases intracranial pressure, causing the brain to shift, lose blood supply, be crushed against the skull, or herniate. Larger hematomas cause more damage. Epidural bleeds can quickly compress the brainstem, causing unconsciousness, abnormal posturing, and abnormal pupil responses to light.[14]

Diagnosis

[edit]Diagnosis is typically by CT scan or MRI.[1] MRIs have greater sensitivity and should be used if there is a high suspicion of epidural hematoma and a negative CT scan.[3] Differential diagnoses include a transient ischemic attack, intracranial mass, or brain abscess.[3]

Epidural hematomas usually appear convex in shape because their expansion stops at the skull's sutures, where the dura mater is tightly attached to the skull. Thus, they expand inward toward the brain rather than along the inside of the skull, as occurs in subdural hematomas. Most people also have a skull fracture.[3]

Epidural hematomas may occur in combination with subdural hematomas, or either may occur alone.[10] CT scans reveal subdural or epidural hematomas in 20% of unconscious people.[15] In the hallmark of epidural hematoma, people may regain consciousness and appear completely normal during what is called a lucid interval, only to descend suddenly and rapidly into unconsciousness later. This lucid interval, which depends on the extent of the injury, is a key to diagnosing an epidural hematoma.[3]

-

Nontraumatic epidural hematoma in a young woman. The grey area in the top right is organizing hematoma, causing midline shift and compression of the ventricle.

-

Non-contrast CT scan of a traumatic acute hematoma in the right fronto-temporal area.

-

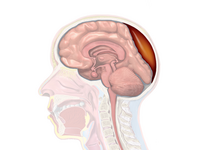

A diagram showing an epidural hematoma.

Treatment

[edit]Epidural hematoma is a surgical emergency. Delayed surgery can result in permanent brain damage or death. Without surgery, death usually follows, due to enlargement of the hematoma, causing a brain herniation.[3] As with other types of intracranial hematomas, the blood almost always must be removed surgically to reduce the pressure on the brain.[9] The hematoma is evacuated through a burr hole or craniotomy. If transfer to a facility with neurosurgery is unavailable, prolonged trephination (drilling a hole into the skull) may be performed in the emergency department.[16] Large hematomas and blood clots may require an open craniotomy.[17]

Medications may be given after surgery. They may include antiseizure medications and hyperosmotic agents to reduce brain swelling and intracranial pressure.[17]

It is extremely rare to not require surgery. If the volume of the epidural hematoma is less than 30 mL, the clot diameter less than 15 mm, a Glasgow Coma Score above 8, and no visible neurological symptoms, then it may be possible to treat it conservatively. A CT scan should be performed, and watchful waiting should be done, as the hematoma may suddenly expand.[3]

Prognosis

[edit]The prognosis is better if there was a lucid interval than if the person was comatose from the time of injury. Arterial epidural hematomas usually progress rapidly. However, venous epidural hematomas, caused by a dural sinus tear, are slower.[3]

Outcomes are worse if there is more than 50 mL of blood in the hematoma before surgery. Age, pupil abnormalities, and Glasgow Coma Scale score on arrival to the emergency department also influence the prognosis. In contrast to most forms of traumatic brain injury, people with epidural hematoma and a Glasgow Coma Score of 15 (the highest score, indicating the best prognosis) usually have a good outcome if they receive surgery quickly.[3]

Epidemiology

[edit]About 2 percent of head injuries and 15 percent of fatal head injuries involve an epidural hematoma. The condition is more common in teenagers and young adults than in older people, because the dura mater sticks more to the skull as a person ages, reducing the probability of a hematoma forming. Males are affected more than females.[3]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Ferri, Fred F. (2016). Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2017 E-Book: 5 Books in 1. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 441. ISBN 9780323448383.

- ^ a b Pooler, Charlotte (2009). Porth Pathophysiology: Concepts of Altered Health States. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 1256. ISBN 9781605477817.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Khairat, Ali; Waseem, Muhammad (2018), "Epidural Hematoma", StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing, PMID 30085524, retrieved 2019-02-13

- ^ a b c d Pryse-Phillips, William (2009). Companion to Clinical Neurology. Oxford University Press. p. 335. ISBN 9780199710041.

Epidural hemorrhage (epidural hematoma, extradural hemorrhage, or hematoma) Bleeding outside the outermost layer of the dural mater, which is thus stripped away from the inner table of the skull or spinal canal.

- ^ a b Epidural Hematoma in Emergency Medicine at Medscape. Author: Daniel D Price. Updated: Nov 3, 2010

- ^ Penn State University (2009). "Probing Question: What is 'Talk and Die' Syndrome?". www.psu.edu. Retrieved 2022-03-26.

- ^ Wagner AL. 2006. "Subdural Hematoma." Emedicine.com. Retrieved on February 6, 2007.

- ^ a b University of Vermont College of Medicine. "Neuropathology: Trauma to the CNS.", March 2005, Retrieved on February 6, 2007.

- ^ a b McCaffrey P. 2001. "The Neuroscience on the Web Series: CMSD 336 Neuropathologies of Language and Cognition." Archived 2007-04-06 at the Wayback Machine California State University, Chico. Retrieved on February 6, 2007.

- ^ a b c Shepherd S. 2004. "Head Trauma." Emedicine.com. Retrieved on February 6, 2007.

- ^ Graham DI and Gennareli TA. Chapter 5, "Pathology of Brain Damage After Head Injury" Cooper P and Golfinos G. 2000. Head Injury, 4th Ed. Morgan Hill, New York.

- ^ Mishra A, Mohanty S (2001). "Contre-coup extradural haematoma: A short report". Neurology India. 49 (94): 94–5. PMID 11303253. Retrieved 2008-01-24.

- ^ a b Kawasumi, Y.; Usui, A.; Hosokai, Y.; Sato, M.; Funayama, M. (2013). "Heat haematoma: Post-mortem computed tomography findings". Clinical Radiology. 68 (2): e95–e97. doi:10.1016/j.crad.2012.10.019. ISSN 0009-9260. PMID 23219455.

- ^ Singh J and Stock A. 2006. "Head Trauma." Emedicine.com. Retrieved on February 6, 2007.

- ^ Downie A. 2001. "Tutorial: CT in Head Trauma" Archived November 6, 2005, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on February 6, 2007.

- ^ Smith SW, Clark M, Nelson J, Heegaard W, Lufkin KC, Ruiz E (2010). "Emergency department skull trephination for epidural hematoma in patients who are awake but deteriorate rapidly". J Emerg Med. 39 (3): 377–83. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2009.04.062. PMID 19535215.

- ^ a b "Epidural hematoma: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 2019-02-12.