Counterfeit consumer good

Top countries whose IP rights are infringed

% total value of seizures, excludes online piracy

[1]

Counterfeit consumer goods are goods illegally made or sold without the brand owner's authorization, often violating trademarks. Counterfeit goods can be found in nearly every industry, from luxury products like designer handbags and watches to everyday goods like electronics and medications. Typically of lower quality, counterfeit goods may pose health and safety risks.

Various organizations have attempted to estimate the size of the global counterfeit market.[2] According to the OECD, counterfeit goods made up approximately 2.5% of global trade in 2019, with an estimated value of $464 billion.[3] Sales of counterfeit and pirated goods are projected to reach €1.67 trillion (approximately $1.89 trillion USD) by 2030.[4]

Description

[edit]A counterfeit consumer good is a product, often of lower quality, that is manufactured or sold without the authorization of the brand owner, using the brand's name, logo, or trademark. These products closely resemble the authentic products, misleading consumers into thinking they are genuine.[5][6] Pirated goods are reproductions of copyrighted products used without permission, such as music, movies or software.[7]: 96 Exact definitions depend on the laws of various countries.

The colloquial terms dupe (duplicate) or knockoff are often used interchangeably with counterfeit, although their legal meanings are not identical. Dupe products are those that copy or imitate the physical appearance of other products but do not copy the brand name or logo of a trademark.[8]

Economic impact

[edit]Sellers of counterfeit goods may infringe on either the trademark, patent or copyright of the brand owner by passing off their goods as made by the brand owner.[9]: 3 Counterfeit products made up an estimated 2.5% of world trade in 2019.[3] Up to 5.8% of goods imported into the European Union in 2019 were counterfeit, according to the OECD.[3][10][11][12] In 2018, Forbes reported that counterfeiting had become the largest criminal enterprise in the world.[13][2] Sales of counterfeit and pirated goods are estimated to reach €1.67 trillion (approximately $1.89 trillion USD) by 2030.[4]

Although counterfeit and pirated goods originate from many economies worldwide, China remains the main source of origin.[3] According to The Counterfeit Report, "China produces 80% of the world's counterfeits and we're supporting China. Whether or not it's their intention to completely undermine and destroy the U.S. economy, we [in the United States] buy about 60% to 80% of the products."[13] It states:

Companies spend millions or billions of dollars building brands, and building reputations and they're being completely destroyed by Chinese counterfeits. And when you take that across a universe of goods, Americans' confidence in their own products is nonexistent. Retailers, the malls, the retail stores are closing up, and we're becoming a duopoly of Walmart and Amazon.[13]

The OECD states that counterfeit products encompass all products made to closely imitate the appearance of the product of another as to mislead consumers. Those can include the unauthorized production and distribution of products that are protected by intellectual property rights, such as copyright, trademarks, and trade names. Counterfeiters illegally copy trademarks, which manufacturers have built up based on marketing investments and the recognized quality of their products, in order to fool consumers.[14] Any product that is protected by intellectual property rights is a target for counterfeiters.[15] Piotr Stryszowski, a senior economist at OECD, notes that it is not only the scale of counterfeiting that is alarming, but its rapidly growing scope, which means that now any product with a logo can become a target.[16]

In many cases, different types of infringements overlap: unauthorized music copying mostly infringes copyright as well as trademarks; fake toys infringe design protection. Counterfeiting therefore involves the related issues of copying packaging, labeling, or any other significant features of the goods.[15]

Among the leading industries that have been seriously affected by counterfeiting are software, music recordings, motion pictures, luxury goods and fashion clothes, sportswear, perfumes, toys, aircraft components, spare parts and car accessories, and pharmaceuticals.[15] Counterfeit pharmaceuticals are the most profitable sector of illegally copied goods, with lost revenues up to $217 billion per year. Fraudulent drugs are known to harm or kill millions around the world, thereby damaging the brand names and sales of major pharmaceutical manufacturers.[17]

Since counterfeits are produced illegally, they are not manufactured to comply with relevant safety standards. They will often use cheap, hazardous and unapproved materials or cut costs in some other manner. These unapproved materials can be hazardous to consumers, or the environment.[18]

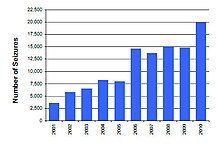

Growing problem

[edit]The OECD estimated that counterfeit goods accounted for around $464 billion, or approximately 2.5% of global trade in 2019.[3] That estimate did not include either domestically produced and consumed products or digital products sold on the internet.[3][15] That estimate rose from 1.8% of world trade in 2007. The OECD concluded that despite their improved interception technologies, "the problem of counterfeit and pirated trade has not diminished, but has become a major threat for modern knowledge-based economies."[15]

In the U.S., despite coordinated efforts by Immigration and Customs Enforcement and Customs and Border Protection (CBP) to stem the influx of counterfeit goods into the U.S., there was a 38% increase in counterfeits seized between 2012 and 2016.[19] In a test survey by the GAO of various items purchased online of major brands, all of which stated they were certified by Underwriters Laboratories, the GAO found that 43% were nonetheless fakes.[19][20]

The approximate cost to the U.S. from counterfeit sales was estimated to be as high $600 billion as of 2016.[21][22] A 2017 report by the Commission on the Theft of American Intellectual Property, stated that China and Hong Kong accounted for 87 percent of counterfeit goods seized entering the United States,[22] and claimed that the Chinese government encourages intellectual property theft.[21][23] Utah Governor Jon Huntsman, who had served as U.S. ambassador to China, stated, "The vast, illicit transfer of American innovation is one of the most significant economic issues impacting U.S. competitiveness that the nation has not fully addressed. It looks to be, must be, a top priority of the new administration."[21] In March 2017 U.S. President Donald Trump signed an executive order to, among other things, ensure the timely and efficient enforcement of laws protecting Intellectual Property Rights holders from imported counterfeit goods.[24]

An Outside magazine article in 2016 discussed the psychology of sales, and the role of gullible consumers, perhaps blindly ignoring warning signs of a "killer deal", somehow justifying buying an item they know is a fake.[25]

Types

[edit]Counterfeiters can include producers, distributors or retail sellers.[26] Growing over 10,000% in the last two decades [when?], counterfeit products exist in virtually every industry sector, including food, beverages, apparel, accessories, footwear, pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, electronics, auto parts, toys, and currency. The spread of counterfeit goods are worldwide, with the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) in 2008 having estimated the global value of all counterfeit goods at $650 billion annually, increasing to $1.77 trillion by 2015.[27] Countries mainly the U.S., U.K., Germany, Austria, Italy, France, Spain, Netherlands, Belgium, Switzerland, Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Finland, South Korea and Japan are among the hardest hit, as their economies thrive on producing high-value products, protected by intellectual property rights, including trademarks.[28] By 2017, the U.S. alone was estimated to be losing up to $600 billion each year to counterfeit goods, software piracy and the theft of copyrights and trade secrets.[21]

Alcoholic beverages

[edit]In 2022 an Europol-Interpol operation called OPSON XI was led by the European Anti-Fraud Office (OLAF) targeting counterfeit and illicit alcoholic beverages. Customs and police authorities seized nearly 14.8 million liters of illicit drinks, including wine and beer. The seized items also included counterfeit bottles, packaging, and equipment for making sparkling wine. OLAF emphasized the dangers of food fraud to consumer health, legitimate businesses, and public revenue.[29]

Wine

[edit]In China, counterfeit high-end wines are a growing beverage industry segment, where fakes are sold to Chinese consumers.[30] Artists refill empty bottles from famous chateaux with inferior vintages. According to one source, "Upwardly mobile Chinese, eager to display their wealth and sophistication, have since developed a taste for imported wine along with other foreign luxuries." In China, wine consumption more than doubled since 2005, making China the seventh-largest market in the world.[31]

The methods used to dupe innocent consumers includes photocopying labels, creating different and phony chateaux names on the capsule and the label. Sometimes authentic bottles are used but another wine is added by using a syringe. The problem is so widespread in China, the U.S. and Europe, that auction house Christie's has begun smashing empty bottles with a hammer to prevent them from entering the black market. During one sale in 2008, a French vintner was "shocked to discover that '106 bottles out of 107' were fakes." According to one source, counterfeit French wines sold locally and abroad "could take on a much more serious amplitude in Asia because the market is developing at a dazzling speed." Vintners are either unable or hesitant to fight such counterfeiters: "There are no funds. Each lawsuit costs 500,000 euros," states one French vintner. In addition, some vintners, like product and food manufacturers, prefer to avoid any publicity regarding fakes to avoid injuring their brand names.[32]

Counterfeit wine is also found in the West, although primarily a problem for collectors of rare wine. Famous examples of counterfeiting include the case of Hardy Rodenstock, who was involved with the so-called "Jefferson bottles,"[33] and Rudy Kurniawan, who was indicted in March 2012 for attempting to sell faked bottles of La Tâche from Domaine de la Romanée-Conti and Clos St. Denis from Domaine Ponsot.[34] In both cases, the victims of the fraud were high-end wine collectors, including Bill Koch, who sued both Rodenstock and Kurniawan over fake wines sold both at auction and privately.[citation needed]

Online sales

[edit]In a report by the U.S. GAO in 2018, approximately 79 percent of the American population had bought products online.[23] They found numerous products which were sold online by Amazon, Walmart, eBay, Sears and Newegg were counterfeit.[35] For 2017 it was estimated that online sales of counterfeit products amounted to $1.7 trillion.[36] Pew Research Center states that worldwide such e-commerce sales are expected to reach over $4 trillion by 2020. CBP has reported that with e-commerce, consumers often import and export goods and services which allows for more cross-border transactions which gives counterfeiters direct access to consumers.[23]

Internet sales of counterfeit goods has been growing exponentially, according to the International Trademark Association, which lists a number of reasons why:

Criminals prefer to sell counterfeits on the Internet for many reasons. They can hide behind the anonymity of the Internet—with the Dark Web even their IP addresses can be hidden. The Internet gives them the reach to sell to consumers globally—outside of the national limits of law enforcement. This international reach forces brand owners to prosecute cases outside of their local jurisdictions. Counterfeiters can display genuine goods on their site and ship counterfeit goods to the consumer. This makes it difficult for brand owners to even determine if a site is selling counterfeits without making costly purchases from the site. Criminal networks are involved with counterfeiting—which leads to hundreds of sites selling the same products on various servers. Making it an arduous task for the brand owner to stop them without working with authorities to take down the counterfeit rings.[37]

Buyers often know they were victimized from online sales, as over a third (34%) said they were victimized two or three times, and 11% said they had bought fake goods three to five times.[36] While many online sellers such as Amazon are not legally responsible for selling counterfeit goods, when items are brought to their attention by a buyer, they will apply a takedown procedure and quickly remove the product listing from their website.[38][39]

In buying counterfeit goods directly from other smaller sellers, location is becoming less a factor, since consumers can purchase products from all over the world and have them delivered straight to their doors by regular carriers, such as USPS, FedEx and UPS. Whereas in previous years international counterfeiters had to transport most counterfeits through large cargo shipments, criminals now can use small parcel mail to avoid most inspections.[40]

Apparel and accessories

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2021) |

According to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in 2016, Ray-Ban, Rolex, Supreme and Louis Vuitton were the most copied brands, with Nike being the most counterfeited brand globally.[41] Counterfeit clothes, shoes, jewelry and handbags from designer brands are made in varying quality; sometimes the intent is only to fool the gullible buyer who only looks at the label and does not know what the real thing looks like, while others put some serious effort into mimicking fashion details.

Others realize that most consumers do not care if the goods they buy are counterfeit and just wish to purchase inexpensive products. The popularity of designer jeans in the late 1970s and early 1980s spurred a flood of counterfeits.[42][43]

Factories that manufacture counterfeit designer brand garments and watches are usually located in developing countries, with between 85% and 95% of all counterfeit goods coming from China.[44]

Expensive watches are vulnerable to counterfeiting as well. In Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam and the Philippines, authentic-looking but poor quality watch fakes with self-winding mechanisms and fully working movements can sell for as little as US$20, with good quality ones selling for $100 and over. Some fakes' movements and materials are also of remarkably passable quality, albeit inconsistently so, and may look good and work well for some years, a possible consequence of increasing competition within the counterfeiting community.

Some counterfeiters have begun to manufacture their goods in the same factory as the authentic goods. 'Yuandan goods' (原单) are those fakes that are produced in the same factory as legitimate designer pieces without authorized permission to do so. These goods are made from scraps and leftover materials from genuine products, produced illegally, and sold on the black market.[44]

Thailand has opened a Museum of Counterfeit Goods, displaying over 4,000 different items in 14 different categories that violate trademarks, patents, or copyrights.[45] The oldest museum of this kind is located in Paris and is known as Musée de la Contrefaçon.

In fashion, counterfeit goods are usually sold on markets and street corners. Though purchasing these goods might seem harmless to those who purchase them knowingly, the National Fraud Intelligence Bureau in England has advised people not to buy counterfeit goods, as their production often funds more serious crime.

Many fashion houses try to stop counterfeits from circulating in the market; Louis Vuitton has an entire team solely focused on stopping counterfeits. Gucci has adapted the counterfeit culture into its designs, changing the spelling of Gucci to 'Guccy' for its spring/summer 2018 collection and painting REAL all over the bags.[46]

Consumers may choose to actively dismiss these unclear origins of product when a trendy style is available for little money. The French terrorist attack in 2015 at Charlie Hebdo has been traced back to being funded by counterfeit products.[47] According to Tommy Hilfiger's Alastair Grey, terrorists bought the guns used with funds gained from selling illegal luxury sneakers. This is more normal than consumers may think. Grey discusses how often sellers will be overlooked by watch-groups, as buying fakes from a distributor in China is less suspicious than other, more extreme criminal activity. The cause and effect of this discounting of crime is giving sellers money to partake in terrorism, human trafficking and child labour.[47] Due to counterfeit shipping papers (which prevent customs from tracking them) and fake brands posing as unremarkable fashion companies but actually selling fake luxury goods, these sellers are challenging to track.

Goods have been brought into the United States without the logos adorned on them in order to get past customs.[48] They are then finished within the country. This is due to the increase in seizing of product at borders. The counterfeiters are reactive to the increasing crackdown on the illegal business practice. Stock-rooms have been replaced with mobile shopping vans that are constantly moving and difficult to track.

Companies like Entrupy are determined to eradicate fake goods with an iPhone application and a standard small camera attachment which uses algorithms to detect even the most indistinguishable "super-fake".[49] Online retailers are also having a difficult time keeping up with monitoring counterfeit items.

Companies all over the internet are illegal e-boutiques that use platforms like eBay, Instagram and Amazon to sell counterfeit goods.[50] Sometimes they own their own websites that have untraceable IP addresses that are often changed.[48] Instagram is a difficult platform to trace, as sellers on it use WeChat, PayPal, and Venmo and typically talk with clients on platforms like WhatsApp. This all makes the transactions seamless and hard to track since payment is done via third party.[51] Listings are also often posted on the story feature; hence, they are not permanent. The problem is getting larger according to Vox and is getting more difficult to monitor.

In 2019, Amazon launched a program known as 'Project Zero' to work with brands to find counterfeit objects on the site.[52] This technology has given private users and companies the capability to gauge handbags certification. Within time, this technology will be widely adaptable to larger platforms. Project Zero offers Amazon partners to flag fake listings without Amazon having to step in.[53] Since Amazon has over five billion listings, a computerized element is also crucial for keeping up with getting rid of fakes. Based on assets and codes provided by Amazon partners, this program scans items and deletes fake ones.[54]

Recently, the battle between counterfeiters and retailers-designers has changed. Shifting opinions among young consumers has created increased demand for 'dupe' products that may not be a direct or illegal counterfeit but a clear copy of a more upmarket design. According to a report released by authentication service Entrupy, 52% of shoppers age 15-24 purchased a counterfeit item in 2022, and 37% of the cohort admits they knew the good was fake when they purchased it.[55] Notably, Chinese e-commerce fast fashion retailer Shein and US e-commerce giant Amazon have enabled this trend.[56] In 2019, multiple brands such as Nike and Birkenstock stopped selling their products on Amazon in protest of the flagrant counterfeits on the platform.[57] Simultaneously, in the luxury market, high fashion brands such as Mugler are beginning to use blockchain technology to provide their products with unique digital identification, make authentication and ownership records simpler and also enabling customers to access unique online content.[58] The European Commission has laid out regulations to require "Digital Product Passports" for new all textile products manufactured in or imported to the EU beginning in 2030.[59]

Electronics

[edit]

Counterfeit electronic components have proliferated in recent years, including integrated circuits (ICs), relays, circuit breakers, fuses, ground fault receptacles, and cable assemblies, as well as connectors. The value of counterfeit electronic components is estimated to total 2% of global sales or $460 billion in 2011.[61] Counterfeit devices have been reverse-engineered (also called a Chinese Blueprint due to its prevalence in China) to produce a product that looks identical and performs like the original, and able to pass physical and electrical tests.[61]

Incidents involving counterfeit ICs has led to the Department of Defense and NASA to create programs to identify bogus parts and prevent them from entering the supply chain.[61] "A failed connector can shut down a satellite as quickly as a defective IC," states product director Robert Hult.[61] Such bogus electronics also pose a significant threat to various sectors of the economy, including the military.[62] In 2012, a U.S. Senate Armed Services Committee report highlighted the risks when it identified approximately 1,800 cases of suspected counterfeit parts in the defense supply chain in 2009 and 2010.[62]

Counterfeit electronic parts can undermine the security and reliability of critical business systems, which can cause massive losses in revenue to companies and damage their reputation.[63] They can also pose major threats to health and safety, such as when an implanted heart pacemaker stops,[64] an anti-lock braking system (ABS) fails, or a cell phone battery explodes.[65]

In 2017 the OECD estimated that one in five (19%) of smartphones sold worldwide were counterfeit, with the numbers growing.[66] Alibaba founder Jack Ma said "we need to fight counterfeits the same way we fight drunk driving."[66] In some African countries, up to 60% of smartphones are counterfeit.[66] Unfortunately, it is nearly impossible for most consumers to spot a fake since telling the difference requires a higher than average level of technical knowledge.[67] Counterfeit phones cause financial losses for owners and distributors of legitimate devices, and a loss of tax income for governments. In addition, counterfeit phones are poorly made, can generate high radiation, contain harmful levels of dangerous elements such as lead, and have a high chance of including malware.[66]

Media

[edit]Compact discs, videotapes, DVDs, computer software and other media that are easily copied can be counterfeited and sold through vendors at street markets,[68] night markets, mail order, and numerous Internet sources, including open auction sites like eBay. If the counterfeit media has packaging good enough to be mistaken for the genuine product, it is sometimes sold as such. Music enthusiasts may use the term bootleg recording to differentiate otherwise-unavailable recordings from counterfeited copies of commercially released material.[citation needed]

In 2014, nearly 30% of the UK population was knowingly or unknowingly involved in some form of piracy through streaming content online or buying counterfeit DVDs, with such theft costing the UK audiovisual industries about £500m a year. Counterfeits are particularly harmful to smaller, independent film-makers, who may have spent years raising money for the film. As a result, the value of intellectual property becomes eroded and films are less likely to be made.[69] In 2018, U.S. agents seized more than 70,000 pirated copies of music and movies from a home in Fresno, California. Although it was a relatively small portion of all imported counterfeits, according to one expert:

The United States government has made intellectual property protection a priority. It seems as if every week we see a new seizure of counterfeiting imports. These efforts are helpful and worthwhile, but U.S. officials and law enforcement can only do so much. Seizure of trademark and copyright infringing imports will hardly make a dent in the global piracy of intellectual property rights.[70]

China has been targeted by the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) for distributing pirated movies and television shows. A selection of websites, internet newsgroups, peer-to-peer online networks and physical locations renowned for sharing illegal content, were presented to officials. Other countries were also listed as sources, including Russia, Brazil, Canada, Thailand and Indonesia.[71] In August 2011, it was reported that at least 22 fake Apple Stores were operating in parts of China, despite others having been shut down in the past by authorities at other locations.[72] The following month, also in China, it was discovered that people were attempting to recreate the popular Angry Birds franchise into a theme park (see here) without permission from its Finnish copyright/trademark owners.[73]

3D printed products

[edit]Counterfeiting of countless items with either large or relatively cheap 3D printers, is a growing problem. The sophisticated printing material and the ever-expanding supply of digital CAD designs available online, will contribute to a black market for counterfeit goods. The Gartner Group estimated that intellectual property loss due to 3D printer counterfeiting could total $100 billion by 2018.[74] Among the technological fields that can be victimized by counterfeits are auto and aircraft parts, toys, medical devices, drugs and even human organs.[75] According to one intellectual property law firm:

The democratization of manufacturing made possible by 3D printing has the potential to lead to counterfeiting on steroids. And, as 3D printers get better and better, faster and faster, and more and more consumer friendly, anyone can become a counterfeiter.[76]

Along with making illicit parts for almost any major product, the fashion industry has become a major target of counterfeiters using 3D printing. The OHIM in 2017 found that approximately 10% of fashion products sold worldwide are counterfeits, amounting to approximately $28.5 billion of lost revenues per year in Europe alone. Industry leaders feared that budding counterfeiters would soon be creating bags, apparel and jewelry at a lower production cost after gaining access to pirated blueprints or digital files from manufacturers.[77]

Toys

[edit]Counterfeit toys leave children exposed to potentially toxic chemicals and the risk of choking. An estimated 10 to 12 percent of toys sold in the UK in 2017 were counterfeit, with the influx of counterfeit goods coming primarily from China. Trading Standards, a UK safety organization, seizes tens of thousands of toys every month to prevent children coming into contact with them, according to the British Toy and Hobby Association (BTHA).[78]

Australian toy manufacturer Moose Toys have experienced problems with counterfeiting of their popular Shopkins toys in 2015.[79] In 2013, five New York-based companies were accused of importing hazardous and counterfeit toys from China. Among the merchandise seized were counterfeit toys featuring popular children's characters such as Winnie the Pooh, Dora the Explorer, SpongeBob SquarePants, Betty Boop, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, Power Rangers, Spider-Man, Tweety, Mickey Mouse, Lightning McQueen and Pokémon.[80] In 2017, the U.S. Customs and Border Protection seized $121,442 worth of counterfeit children's toys that arrived into port from China and was destined for a North Carolina-based importer. The shipment was found to contain multiple items bearing trademarks and copyrights registered to Cartoon Network, Saban Brands, and Danjaq, LLC.[81]

Pharmaceuticals

[edit]

According to the U.S. FBI, the counterfeiting of pharmaceuticals accounts for an estimated $600 billion in global trade, and may be the "crime of the 21st century." They add that it "poses significant adverse health and economic consequences for individuals and corporations alike." The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that over 30% of pharmaceuticals in developing countries are fake, stating that "Anyone, anywhere in the world, can come across medicines seemingly packaged in the right way but which do not contain the correct ingredients and, in the worst-case scenario, may be filled with highly toxic substances."[82][83]

About one-third of the world's countries lack effective drug regulatory agencies, which makes them easy prey for counterfeiters. Globally, more than half of counterfeit pharmaceuticals sold are for life-threatening conditions, such as malaria, tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS, and cancer.[17] An estimated one million people die each year from taking toxic counterfeit medication.[17]

With the increase of internet sales, such fake drugs easily cross international boundaries and can be sold directly to unsuspecting buyers. In September 2017, Interpol, after a 10-year investigation, took down 3,584 websites in various countries, removed 3,000 online ads promoting illicit pharmaceuticals, and arrested 400 people.[84]

The majority of online pharmacies taken down did not require a prescription to order the medicines and most sold potentially dangerous bogus versions of real drugs. One target for the operation was the illicit trade in opioid painkillers, especially fentanyl, which is 50 to 100 times stronger than morphine. Counterfeit versions of other narcotics like OxyContin and Percocet also contain fentanyl as a key ingredient. Online pharmacies had flooded the US market and contributed to the opioid epidemic,[84] with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) claiming that sixty-six percent (66%) of the 63,600 overdose deaths in 2016 were caused by opioids, including fentanyl. The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) found that "customers can purchase fentanyl products from Chinese laboratories online with powdered fentanyl and pill presses" which are then shipped directly to buyers via regular mail services such as USPS, DHL, FedEx, and UPS.[85]

Buyers are attracted to rogue online pharmacies since they pose as legitimate businesses.[86] Consumers are motivated by lower prices, and some are attracted by the ability to obtain prescription drugs without a prescription. Of the drugs bought online, however, 90 percent are found to come from a country different from one the website claims.[17] A 2018 report by the DHS

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) defines counterfeit drugs as those sold under a product name without proper authorization:

- "Counterfeiting can apply to both brand name and generic products, where the identity of the source is mislabeled in a way that suggests that it is the authentic approved product. Counterfeit products may include products without the active ingredient, with an insufficient or excessive quantity of the active ingredient, with the wrong active ingredient, or with fake packaging."[87]

According to The Economist, between 15%-30% of antibiotic drugs in Africa and South-East Asia are fake, while the UN estimated in 2013 that roughly half of the antimalarial drugs sold in Africa—worth some $438m a year—are counterfeit.[88] In early 2018 29 tons in counterfeit medicine were seized by Interpol in Niger.[89]

Pfizer Pharmaceuticals has found fake versions of at least 20 of its products, such as Viagra and Lipitor, in the legitimate supply chains of at least 44 countries. Pfizer also found that nearly 20% of Europeans had obtained medicines through illicit channels, amounting to $12.8 billion in sales. Other experts estimate the global market for fake medications could be worth between $75 billion and $200 billion a year, as of 2010.[90]

Other prescription drugs that have been counterfeited are Plavix, used to treat blood clots, Zyprexa for schizophrenia, Casodex, used to treat prostate cancer, Tamiflu, used to treat influenza, including Swine flu, and Aricept, used to treat Alzheimers.[91] The EU reported that as of 2005 India was by far the biggest supplier of fake drugs, accounting for 75 percent of the global cases of counterfeit medicine. However, many drugs and other consumer products that were supposedly made in India, were actually made in China and imported into India.[92]

Another 7% came from Egypt and 6% from China. Those involved in their production and distribution include "medical professionals" such as corrupt pharmacists and physicians, organized crime syndicates, rogue pharmaceutical companies, corrupt local and national officials, and terrorist organizations.[7]

Food

[edit]Food fraud, "the intentional adulteration of food with cheaper ingredients for economic gain," is a well-documented crime that has existed in the U.S. and Europe for many decades. As of 2014,[update] it has only received more attention in recent years as the fear of bioterrorism has increased. Numerous cases of intentional food fraud have been discovered. As of 2013,[update] the foods most commonly listed as adulterated or mislabelled in the United States Pharmacopeia Convention's Food Fraud Database were: milk, olive oil, honey, saffron, fish, coffee, orange juice, apple juice, black pepper, and tea.[93] A 2014 report by the U.S. Congressional Research Service listed the leading food categories with reported cases of fraud as olive oil; fish and seafood; milk and milk-based products; honey, maple syrup, and other natural sweeteners; fruit juice; coffee and tea; spices; organic foods and products; and clouding agents.[94] Deceptive and inaccurate ingredient lists are increasingly common.[95]

United States

[edit]- In 2008, U.S. consumers were "panicked" and a "media firestorm" ensued when Chinese milk was discovered to have been adulterated with the chemical melamine, to make milk appear to have a higher protein content in government tests. It caused 900 infants to be hospitalized and resulted in six deaths.[96]

- In 2007, the University of North Carolina found that 77 percent of fish labeled as red snapper was actually tilapia, a common and less flavorful species. The Chicago Sun-Times tested fish at 17 sushi restaurants found that fish being sold as red snapper actually was mostly tilapia. Other inspections uncovered catfish being sold as grouper, which normally sells for nearly twice as much as catfish.[96] Fish is the most frequently faked food Americans buy, which includes "...selling a cheaper fish, such as pen-raised Atlantic salmon, as wild Alaska salmon." In one test, Consumer Reports found that less than half of supposedly "wild-caught" salmon sold in 2005-2006 were actually wild, and the rest were farmed.[97]

- French cognac was discovered to have been adulterated with brandy, and their honey was mixed with cheaper sugars, such as high-fructose corn syrup.[96]

- In 2008, U.S. food safety officers seized more than 10,000 cases of counterfeit extra virgin olive oil, worth more than $700,000 from warehouses in New York and New Jersey.[96] Olive oil is considered one of the most frequently counterfeited food products, according to the FDA, with one study finding that many products labeled as "extra-virgin olive oil" actually contained up to 90% soybean oil.[97]

- From 2010 until 2012, the conservation group Oceana analyzed 1,200 seafood samples from 674 retail outlets in 21 U.S. states. A third of the samples contained the DNA of a different type of fish to the one stated on the product label.[98] They found that fish with high levels of mercury such as tilefish and king mackerel were being passed off as relatively safe fish like grouper. Snapper (87%) and tuna (59%) were the most commonly mislabeled species.[99]

- Genetic testing by the Boston Globe in 2011 found widespread mislabelling of fish served in area restaurants.[100]

- The "secondary" grocery industry is susceptible to food fraud by diverting products deemed unfit for consumption.[101]

The Food and Drug Administration, the primary regulatory body for food safety and enforcement in the United States, admits that the "sheer magnitude of the potential crime" makes prevention difficult, along with the fact that food safety is not treated as a high priority. They note that with more than 300 ports of entry through which 13 percent of America's food supply passes, the FDA is only able to inspect about two percent of that food.[96]

New U.S. seafood tracing regulations were announced by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in 2015.[102]

Europe

[edit]Food counterfeiting is a serious threat in Europe, especially for countries with a high number of trademark products such as Italy. In 2005, EU customs seized more than 75 million counterfeited goods, including foods, medicines and other goods, partly due to Internet sales. More than five million counterfeit food-related items, including drinks and alcohol products, were seized. According to the EU's taxation and customs commissioner, "A secret wave of dangerous fakes is threatening the people in Europe."[103]

Incidents

[edit]- The 2008 Irish pork crisis was pork contaminated with dioxins.

- The 2013 horse meat scandal was a multinational incident involving horse meat (and pork) being found in food products that were labelled as only containing beef.

- The 2013 European aflatoxin contamination scandal involved milk contaminated with aflatoxins.

Asia

[edit]Food fraud is a growing concern in Asia–Pacific.[104] Examples include the injection of non-food grade gels into shrimp and prawns to increase their weight and visual appeal[104] and gutter oil.

Cosmetics

[edit]U.S. Customs and Border Protection suggest that the cosmetic industry is losing about $75 million annually based on the amount of imitation products that are smuggled into the U.S. each year. In addition to the lost revenue, cosmetics brands are damaged when consumers experience unhealthy side effects, such as eye infections or allergic reactions, from counterfeit products.[105]

Customs agents seized more than 2,000 shipments of counterfeit beauty products in 2016, and noted that fake personal care items were more common than counterfeit handbags. One of the biggest threats to beauty consumers is the risk that they are buying counterfeit products on familiar 3rd party retail platforms like Amazon.[105]

Cigarettes

[edit]Illicit cigarettes are an example of the multi-pronged threat of counterfeiting, providing hundreds of millions of dollars per year to terrorist groups.[106]

The harm arising from this amalgam of contaminants sits on top of any baseline hazard ascribed to commercial tobacco products. With the sales of illicit cigarettes in Turkey, for example, exceeding 16.2 billion cigarettes per year, Turkish Prime Minister Erdogan labeled counterfeit tobacco as "more dangerous than terrorism".[107]

Military items

[edit]According to a U.S. Senate committee report in 2012 and reported by ABC News, "counterfeit electronic parts from China are 'flooding' into critical U.S. military systems, including special operations helicopters and surveillance planes, and are putting the nation's troops at risk." The report notes that Chinese companies take discarded electronic parts from other nations, remove any identifying marks, wash and refurbish them, and then resell them as brand-new – "a practice that poses a significant risk to the performance of U.S. military systems.[108][109]

In this case however, it is usually not the components themselves which are counterfeit: they have in most instances been fabricated by the expected manufacturer or by a licensee who has paid for the appropriate intellectual property. Rather, what is fraudulent is the issuing by the reseller of a Certificate of Conformity that claims that their provenance is traceable, sometimes accompanied by the components being remarked to make it appear that they have been manufactured and tested to more stringent standards than is actually the case.[citation needed]

There have, however, been situations where components have been fully counterfeit. A fairly typical example is that of USB to Serial port "dongles" ostensibly manufactured by FTDI, Prolific and others which in practice contain a general-purpose microcontroller which has been programmed to implement the same programming interface to a greater or lesser extent. Another example is that of electrolytic capacitors which have been sold as originating from a highly regarded manufacturer but in practice are merely shells which contain a lower-specification (and physically smaller) component internally.[110]

Other counterfeit product categories

[edit]These include items which purport to be original art, designer watches, designer china, accessories such as sunglasses and handbags, and all varieties of antiques. In some cases the copying process has proceeded through several vendors, and it is possible to see gradual changes as the chain of "counterfeits of counterfeits" progresses.[citation needed]

These products frequently show up for sale on online sites such as Amazon and eBay. Efforts to report them as fraudulent receive little response.[citation needed]

Enforcement

[edit]United States

[edit]On November 29, 2010, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security seized and shut down 82 websites as part of a U.S. crackdown of websites that sell counterfeit goods, and was timed to coincide with "Cyber Monday," the start of the holiday online shopping season.[111] Attorney General Eric Holder announced that "by seizing these domain names, we have disrupted the sale of thousands of counterfeit items, while also cutting off funds to those willing to exploit the ingenuity of others for their own personal gain."[112] Members of Congress proposed the PROTECT IP Act to block access to foreign Web sites offering counterfeit goods.

Some U.S. politicians are proposing to fine those who buy counterfeit goods, such as those sold in New York's Canal Street market. In Europe, France has already created stiff sentences for sellers or buyers, with punishments up to 3 years in prison and a $300,000 fine.[113] Also in Europe, non-profit organizations such as the European Anti-Counterfeiting Network, fight the global trade in counterfeit goods.[114]

During a counterfeit bust in New York in 2007, federal police, with the help of local Private Investigator Ray Dowd, seized $200 million in fake designer clothing, shoes, and accessories from one of the largest-ever counterfeit smuggling rings. Labels seized included Chanel, Nike, Burberry, Ralph Lauren and Baby Phat. Counterfeit goods are a "...major plague for fashion and luxury brands," and numerous companies have made legal efforts to block the sale of counterfeits from China. Many of the goods are sold to retail outlets in Brooklyn and Queens.[115]

For trademark owners wishing to identify and prevent the importation of counterfeit goods, the U.S. Customs and Border Protection agency supports a supplemental registration of trademarks through their Intellectual Property Rights e-Recordation program.[116][117] In 2017, U.S. President Donald Trump signed an executive order to, among other things, ensure the timely and efficient enforcement of laws protecting intellectual property rights holders from imported counterfeit goods.[24]

Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA)

[edit]In October 2011, a bill was introduced entitled Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA). If the bill had been passed, it would have expanded the ability of U.S. law enforcement and copyright holders to fight online trafficking in copyrighted intellectual property and counterfeit goods. The bill would have allowed the U.S. Department of Justice, as well as copyright holders, to seek court orders against websites accused of enabling or facilitating copyright infringement. Opponents of the bill stated that it could have crippled the Internet through selective censorship and limiting free speech. In regards to the bill, the Obama administration stressed that "the important task of protecting intellectual property online must not threaten an open and innovative internet."[118] The legislation was later withdrawn by its author, Rep. Lamar Smith.[119]

China

[edit]In China counterfeiting is so deeply rooted that crackdowns on shops selling counterfeit cause public protests during which the authorities are derided as "bourgeois puppets of foreigners."[120]

The 2018 E-Commerce Law, along with the Consumer Protection Law, require e-commerce platforms to take proper action if they are aware or should be aware of fraudulent online behavior by merchants, including the sales of fraudulent goods.[121]: 207 If merchants are found to have sold counterfeit goods, the Consumer Protection Law imposes a penalty of three times their value to compensate consumers.[121]: 207 If platforms have prior knowledge of counterfeit goods being sold, then the E-Commerce Law makes them jointly liable with merchants engaged in sale of such goods.[121]: 231 These risks also prompted platforms to take a stricter view towards shanzhai products.[121]: 231

Other countries

[edit]On October 1, 2011, the governments of eight nations including Japan and the United States signed the Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement (ACTA), which is designed to help protect intellectual property rights, especially costly copyright and trademark theft. The signing took place a year after diligent negotiations among 11 governments: Australia, Canada, the European Union, Japan, the Republic of Korea, Mexico, Morocco, New Zealand, Singapore, Switzerland and the United States. As of 2011, the EU, Mexico, Switzerland and China had not yet signed the agreement.[122] Due to the latter, critics evaluated the agreement as insubstantial.[123][124]

Countries like Nigeria fight brand trademark infringement on a national level but the penalties are dwarfed by the earnings outlook for counterfeiters: "As grievous as this crime is, which is even worse than armed robbery, the penalty is like a slap on the palm, the most ridiculous of which is a fine of 50,000 naira ($307). Any offender would gladly pay this fine and return to business the next day."[125]

In early 2018 Interpol confiscated tonnes of fake products worth $25 million and arrested hundreds of suspects and broke up organized crime networks in 36 different countries on four continents. They raided markets, chemists, retail outlets, warehouses and border control points, where they seized among other things, pharmaceuticals, food, vehicle parts, tobacco products, clothing, and agrochemicals. Over 7.2 million counterfeit and illicit items weighing more than 120 tonnes were confiscated.[126]

Human rights laws

[edit]Counterfeit products are often produced in violation of basic human rights and child labor laws and human rights laws, as they are often created in illegal sweatshops.[127] Clothing manufacturers often rely on sweatshops using children in what some consider "slave labor" conditions. According to one organization, there are some 3,000 such sweatshops in and around Buenos Aires, Argentina.[128] Author Dana Thomas described the conditions she witnessed in other country's sweatshops, noting that children workers are often smuggled into countries and sold into labor:

I remember walking into an assembly plant in Thailand a couple of years ago and seeing six or seven little children, all under 10 years old, sitting on the floor assembling counterfeit leather handbags. The owners had broken the children's legs and tied the lower leg to the thigh so the bones wouldn't mend. [They] did it because the children said they wanted to go outside and play. . . I went on a raid in a sweatshop in Brooklyn, and illegal workers were hiding in a rat hole, [and] impossible to know how old the workers were.[129]

U.S. Supreme Court justice Sonia Sotomayor, who has tried to prosecute counterfeiters, notes that major industries have suffered the loss of hundreds of thousands of jobs due to the exploitation of child labor in sweatshops in New York and Asia. Those often produce dangerous merchandise, such as fake auto parts or toys, made of toxic and easily breakable materials.[130]

The profits often support terrorist groups,[131] drug cartels,[132] people smugglers[133] and street gangs.[134] The FBI has found evidence that a portion of the financing of the 1993 World Trade Center bombing came from a store selling counterfeit T-shirts.[130] The same has been found surrounding many other organized crime activities. According to Bruce Foucart, director of US Homeland Security's National Intellectual Property Coordination Centre, the sales of counterfeit goods funded the Charlie Hebdo attack of 2016 in Paris, which left 12 people dead and nearly a dozen more injured.[44] Sales of pirated CDs have been linked to funding the 2004 Madrid train bombing, and investigations firm Carratu connects money from counterfeit goods to Hezbollah, Al Qaeda, the Japanese Yakuza, the ETA, and the Russian Mob.

The crackdown on counterfeit goods has not only become a matter of human rights but one of national and international security in various countries. The FBI has called product counterfeiting "the crime of the 21st century."[135]

Internet shopping sites

[edit]Major internet shopping sites, such as Amazon.com, eBay.com, and Alibaba.com, provide complaint pages where listings of counterfeit goods can be reported. The reporter must show that it owns the intellectual property (e.g. trademark, patent, copyright) being presented on the counterfeit listings. The shopping site will then do an internal investigation and if it agrees, it will take the counterfeit listing down.[136][137] The actual execution of such investigations, at least, on Amazon and eBay, seems to be limited in reality.[citation needed]

Social media platforms

[edit]Besides online market sites, the shift to digital for luxury and consumer goods have led to both promising opportunities and serious risks. The British government released a study stating 1/5 of all items tagged with luxury good brand names on Instagram are fakes with 20% of the posts featuring counterfeit goods from accounts usually based in China, Russia, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Ukraine. It also highlights the scale, impact, and characteristics of infringement, and that sophistication from counterfeiters continues to grow through social media platforms.[138] In 2016, in a span of 3-day period, Instagram has identified 20,892 fake accounts selling counterfeit goods, collectively responsible for 14.5 million posts, 146,958 new images and gaining 687,817 new followers, with Chanel (13.90%), Prada (9.69%) and Louis Vuitton (8.51%) being the top affected brands according to a study from The Washington Post.[139]

Social media and mobile applications have turned into ideal platforms for transactions and trades. Counterfeit users and sellers would set up online accounts on Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook and post counterfeit or illicit products through ways of sponsored ads and deals. The consumer can easily contact buyers and purchase the counterfeit goods unknowingly by email, WhatsApp, WeChat, and PayPal. As social media watchdogs and groups[clarification needed] are working on cracking and shutting down accounts selling counterfeit goods, counterfeiters continue to operate 24 hours with advanced systems in algorithms, artificial intelligence, and spambots using tactics involving automatic account creation, avoidance in detection and tax-and-duty-free law. It is advised by many that brands, tech platforms, governments and consumers require a comprehensive strategy and cross-sector collaboration to combat the multifaceted system enabling the international counterfeit market.[140]

So far, only United Kingdom, Scotland and Erie representatives have taken the initiative by using law enforcement and criminal charges to fight against counterfeiting and piracy on social media accounts.[141] This concern still needs tremendous effort in updating its enforcement policies in online counterfeiting. Below are some emerging solutions suggested by World Trademark Review:

- Social media surveillance – New technical filters and deploy further resources; engaging in open information sharing; and promoting broader awareness in public campaigns

- Continued enforcement measures – Rogue website actions; customs training and cooperation with law enforcement; and addressing counterfeit goods at the source

- Reinforce in postal service – advance data screening for mail parcels and shipments

- Adopting a set of best practices in payment processors

- Collaborate with third-party cooperation for reliance

Anti-counterfeiting packaging

[edit]Packaging can be engineered to help reduce the risks of package pilferage or the theft and resale of products: Some package constructions are more resistant to pilferage and some have pilfer indicating seals. Counterfeit consumer goods, unauthorized sales (diversion), material substitution and tampering can all be reduced with these anti-counterfeiting technologies. Packages may include authentication seals and use security printing to help indicate that the package and contents are not counterfeit; these too are subject to counterfeiting. Packages also can include anti-theft devices, such as dye-packs, RFID tags, or electronic article surveillance[142] tags that can be activated or detected by devices at exit points and require specialized tools to deactivate. Anti-counterfeiting technologies that can be used with packaging include:

- 2D barcodes - data codes that can be tracked

- Color shifting ink or film - visible marks that switch colors or texture when tilted

- DNA tracking - genes embedded onto labels that can be traced

- Encrypted micro-particles - unpredictably placed markings (numbers, layers, and colors) not visible to the human eye

- Forensic markers

- Holograms - graphics printed on seals, patches, foils or labels and used at point of sale for visual verification

- Kinetic diffraction grating images

- Micro-printing - second line authentication often used on currencies

- NFC (Near Field Communication) tagging for authentication - short-range wireless connectivity that stores information between devices

- Overt and covert feature

- QR code

- Security pigments and inks - marks only visible under ultraviolet light and is not under normal lighting conditions

- Security tape and labels

- Serialized barcodes

- Tactile prints - dots printed directly onto surface of the product, provide embossed finishes to highlight specific design features

- Tamper evident seals and tapes - destructible or graphically verifiable at point of sale

- Taggant fingerprinting - uniquely coded microscopic materials that are verified from a database

- Track and trace systems - use codes to link products to database tracking system

- Water indicators - become visible when contacted with water

With the increasing sophistication of counterfeiters techniques, there is an increasing need for designers and technologists to develop even more creative solutions to distinguish genuine products from frauds, incorporating unique and less obvious aspects of identification into the design of goods. One of the most impressive of techniques exploits anisotropic optical characteristics of conjugated polymers.[143] Engineers have developed specialized markings and patterns that can be incorporated within the designs of textiles that can only be detected under polarized lights. Similar to methods implemented in the production of currency, invisible threads and dyes are used to create unique designs within the weaves of luxury textiles that cannot be replicated by counterfeiters due to a unique set of fibres, anisotropic tapes, and polymer dyes used by the brand and manufacturer.[143]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Global trade in fake goods worth nearly half a trillion dollars a year". OECD & EUIPO. April 18, 2016. Archived from the original on June 2, 2016. Retrieved February 20, 2024.

- ^ a b Bharadwaj, Vega; Brock, Marieke; Heing, Bridey; Miro, Ramon; Mukarram, Noor (2020). "U.S. Intellectual Property and Counterfeit Goods—Landscape Review of Existing/Emerging Research". SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3577710. ISSN 1556-5068.

- ^ a b c d e f "Global Trade in Fakes". OECD. June 21, 2021. Retrieved October 11, 2024.

- ^ a b "Trade in Counterfeit Goods Market Set to Reach €1.67 Trillion in 2030 – Corsearch". AP News. May 16, 2024. Retrieved October 11, 2024.

- ^ "Counterfeiting (Intended for a non-legal audience)". International Trademark Association. Retrieved October 11, 2024.

- ^ "What is Counterfeiting". International AntiCounterfeiting Coalition. Retrieved October 11, 2024.

- ^ a b The Economic Impact of Counterfeiting and Piracy, OECD (2008)

- ^ Mull, Amanda (February 24, 2023). "Shoppers Are Stuck in a Dupe Loop". The Atlantic. Retrieved April 16, 2023.

- ^ Chaudhry, Peggy E., Zimmerman, Alan. The Economics of Counterfeit Trade: Governments, Consumers, Pirates and Intellectual Property Rights, Springer Science & Business Media (2009)

- ^ "Global trade in fake goods worth nearly half a trillion dollars a year - OECD & EUIPO". OECD. April 18, 2016.

- ^ "Knocked out by knock-offs: Counterfeit products, mostly from China, are hurting Indian brands". DNA India. January 31, 2018. Retrieved September 25, 2023.

- ^ Pathak, Sriparna (June 26, 2018). "How Chinese counterfeiting hurts India". Asia Times. Retrieved September 25, 2023.

- ^ a b c Shepard, Wade (March 29, 2019). "Meet The Man Fighting America's Trade War Against Chinese Counterfeits (It's Not Trump)". Forbes. Retrieved September 25, 2023.

- ^ "Combating trademark and product piracy". Zoll online. Archived from the original on February 5, 2007. Retrieved December 6, 2006.

- ^ a b c d e "Trade in Counterfeit and Pirated Goods: Mapping the Economic Impact | READ online". oecd-ilibrary.org. April 18, 2016. Retrieved September 25, 2023.

- ^ "Sale of fake goods hits alarming level". The Edge Markets. April 2, 2018. Retrieved September 25, 2023.

- ^ a b c d "Fighting counterfeit pharmaceuticals: New defenses for an underestimated - and growing - menace". Strategy&. June 29, 2017. Retrieved September 25, 2023.

- ^ "Counterfeit goods: How to tell the real from the rip-off". Archived from the original on June 1, 2020. Retrieved June 2, 2017.

- ^ a b "U.S. Customs Needs To Share More Info on Counterfeits With Online Retailers". Nextgov.com. March 6, 2018. Retrieved September 25, 2023.

- ^ "Popular goods sold through Amazon, Walmart and others are counterfeits: Government report - CBS News". www.cbsnews.com. February 26, 2018. Retrieved September 25, 2023.

- ^ a b c d "Counterfeit Goods Cost the U.S. $600 Billion a Year". AP. February 27, 2017.

- ^ a b "IP Commission Report", The National Bureau of Asian Research, 2017

- ^ a b c "Intellectual Property: Agencies Can Improve Efforts to Address Risks Posed by Changing Counterfeits Market", U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), January 2018

- ^ a b "Presidential Executive Order on Establishing Enhanced Collection and Enforcement of Antidumping and Countervailing Duties and Violations of Trade and Customs Laws – The White House". trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov. March 31, 2017. Retrieved September 25, 2023.

- ^ Lindsey, Joe (May 10, 2016). "RFID Tags Won't Stop Counterfeiting". Outside Online. Retrieved September 16, 2018.

- ^ "Knock-off the Knockoffs: The Fight Against Trademark and Copyright Infringement – Illinois Business Law Journal". September 21, 2009. Retrieved September 25, 2023.

- ^ "Global Impacts Study | ICC - International Chamber of Commerce". www.iccwbo.org. Archived from the original on June 1, 2020. Retrieved February 24, 2016.

- ^ "Counterfeit Goods Shaving Billions From Italian Economy". Financial Tribune. June 26, 2018. Retrieved September 25, 2023.

- ^ "14.8 million litres alcoholic drinks seized across Europe - European Commission". anti-fraud.ec.europa.eu.

- ^ Paull, John (2012) "China fakes Australian premium organic wine", Organic News, June 26.

- ^ "Pricey counterfeit labels proliferate as China wine market booms" Los Angeles Times, January 14, 2012

- ^ "After luxury bags, counterfeit luxury wines", Luxuo.com, November 22, 2009

- ^ The New Yorker, September 3, 2007: The Jefferson Bottles, p. 2

- ^ "USA v. Kurniawan" (PDF). Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- ^ "Video New warning of counterfeit products sold online". ABC News. February 28, 2018. Retrieved September 25, 2023.

- ^ a b "One-Third of Online Shoppers Victims of Counterfeit Sales – 24/7 Wall St". December 18, 2017. Retrieved September 25, 2023.

- ^ "Addressing the Sale of Counterfeits on the Internet", International Trademark Association, 2018

- ^ Semuels, Alana (April 20, 2018). "Amazon May Have a Counterfeit Problem". The Atlantic. Retrieved September 25, 2023.

- ^ Levy, Ari (July 8, 2016). "Amazon's Chinese counterfeit problem is getting worse". CNBC. Retrieved September 25, 2023.

- ^ "What We Know – and What We Don't – About Counterfeit Goods and Small Parcels". www.theglobalipcenter.com. March 7, 2018. Retrieved September 25, 2023.

- ^ "Nike Shoes Among Most Counterfeited Goods in the World". ABC News. April 18, 2016. Retrieved November 9, 2023.

- ^ Johnson, Janis (February 5, 1981). "Counterfeit jeans". The Washington Post.

- ^ Schiro, Anne-Marie (April 4, 1981). "Keeping jeans honest". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 17, 2024.

- ^ a b c "Counterfeit Fashion Is Funding Terrorism, Sweatshops, and Untold Human Misery". Esquire. December 21, 2016. Retrieved April 3, 2017.

- ^ "Museum of Counterfeit Goods" Archived October 20, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, Tilleke & Gibbins International, Thailand, accessed March 8, 2014

- ^ "Is Counterfeiting Actually Good for Fashion? | Highsnobiety". Highsnobiety. October 31, 2018. Retrieved October 31, 2018.

- ^ a b Gray, Alastair (December 6, 2017), How fake handbags fund terrorism and organized crime, retrieved October 26, 2019

- ^ a b Thomas, Dana (January 9, 2009). "The Fight Against Fakes". Harper's BAZAAR. Retrieved October 26, 2019.

- ^ Mau, Dhani (June 6, 2019). "Can Technology Keep Fake Handbags Out of the Marketplace?". Fashionista. Retrieved October 26, 2019.

- ^ Street, Mikelle (December 21, 2016). "Counterfeit Fashion Is Funding Terrorism, Sweatshops, and Untold Human Misery". Esquire. Retrieved October 26, 2019.

- ^ Lieber, Chavie (May 2, 2019). "Instagram has a counterfeit fashion problem". Vox. Retrieved October 26, 2019.

- ^ Lee, Adriana (March 1, 2019). "Amazon Weaponizes Brands, AI in Fight Against Fakes". WWD. Retrieved October 26, 2019.

- ^ "Amazon launches new tools that allow brands to proactively fight counterfeiting". TechCrunch. February 28, 2019. Retrieved October 26, 2019.

- ^ Lee, Adriana (March 4, 2019). "Amazon Weaponizes Brands, AI in Fight Against Fakes". Women's Wear Daily.

- ^ Klara, Robert (November 15, 2023). "Gen Z Doesn't Care If Their Luxury Merch Is Counterfeit". www.adweek.com. Retrieved November 17, 2023.

- ^ Jones, C. T. (September 15, 2022). "How 'Dupe' Culture Took Over Online Fashion". Rolling Stone. Retrieved November 9, 2023.

- ^ Suthivarakom, Ganda (February 11, 2020). "Welcome to the Era of Fake Products". Wirecutter: Reviews for the Real World. Retrieved November 9, 2023.

- ^ Templeton, Lily (November 7, 2023). "EXCLUSIVE: Mugler Teams Up With Arianee for Digital Passports in Bags". WWD. Retrieved November 9, 2023.

- ^ "Ecodesign for sustainable products". commission.europa.eu. Retrieved November 9, 2023.

- ^ Ahi, Kiarash (May 13, 2015). Anwar, Mehdi F; Crowe, Thomas W; Manzur, Tariq (eds.). "Terahertz characterization of electronic components and comparison of terahertz imaging with X-ray imaging techniques". SPIE Sensing Technology+ Applications. Terahertz Physics, Devices, and Systems IX: Advanced Applications in Industry and Defense. 9483: 94830K–94830K–15. Bibcode:2015SPIE.9483E..0KA. doi:10.1117/12.2183128. S2CID 118178651.

- ^ a b c d Hult, Robert (November 5, 2013). "Challenging the Counterfeit Connector Conundrum". Connector and Cable Assembly Supplier. Retrieved September 25, 2023.

- ^ a b "The Serious Risks From Counterfeit Electronic Parts". Forbes. July 11, 2012.

- ^ Tehranipoor, Mark. Counterfeit Integrated Circuits: Detection and Avoidance, Springer (2015) p. 5

- ^ "Counterfeit Products On The Rise"[permanent dead link], Robert J. McGuirl Law Firm

- ^ "Exploding Cell Phones Spur Recalls", CBS News, October 28, 2014

- ^ a b c d "New Tricks Needed to Stop the €45 Billion Counterfeit Smartphone Market", Developing Telecoms, November 9, 2017

- ^ "Top 5 reasons why counterfeit goods are getting harder to spot", IP Watchdog, June 26, 2018

- ^ Eichhofer, André (June 13, 2012). "Dealers Do Roaring Trade in Fake Euro 2012 Goods". Der Spiegel. Retrieved June 13, 2012.

- ^ "Movie piracy: threat to the future of films intensifies", The Guardian, July 17, 2014

- ^ "Nearly $1 Million Worth of Counterfeit Movies and Music Seized", Chester Law, March 20, 2018

- ^ "China is still a notorious market for movie and TV show piracy, report says", South China Morning Post, October 29, 2013

- ^ "22 more fake Apple stores found in Kunming, China, says report", CBS News, August 11, 2011

- ^ "China steals "Angry Birds" for theme park", CBS News, September 16, 2011

- ^ "Illegal, Immoral, and Here to Stay Counterfeiting and the 3D Printing Revolution", Wired, February 20, 2015

- ^ "Germany: Counterfeiting, 3D printing and the third Industrial Revolution", World Trademark Review, January 1, 2017

- ^ "How to Tell What’s Real and What’s Fake in a 3D Printed World", 3D Printing Industry, Feb. 5, 2014

- ^ "The New World of 3D Printing … and Counterfeiting" Archived July 16, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, The Fashion Law, March 28, 2017

- ^ "A deluge of counterfeit toys is leaving children exposed to toxic chemicals, safety experts warn", I News, January 23, 2018

- ^ [1] PR Newswire, "Police Raid Chinese Toy Factory: Moose Enterprise and Local Police Seize Over 150,000 Counterfeit Shopkins Toys in China", July 31, 2015

- ^ "5 accused of importing counterfeit, hazardous toys", CNN, February 7, 2013

- ^ "Charleston CBP Seizes Counterfeit Toys", U.S. Customs and Border Protection, July 26, 2017

- ^ "Counterfeit Pharmaceuticals and Public Health" Archived July 8, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, Michigan State Univ., Public Health dept

- ^ Shafy, Samiha (January 30, 2008). "Counterfeit drugs consist of pills, drops and ointments containing either incorrect active ingredients or none at all. Sometimes the active ingredients are so diluted that the drugs are completely ineffective". Der Spiegel. Retrieved January 30, 2008.

- ^ a b "Latest Interpol-led Pangea op nets rogue pharmacies", Securing Industry, September 26, 2017

- ^ "Combatting the Opioid Crisis: Exploiting Vulnerabilities in International Mail", Report of the Committee on Homeland Security, January 24, 2018

- ^ Blackstone, EA; Fuhr, JP Jr; Pociask, S (2014). "The health and economic effects of counterfeit drugs". Am Health Drug Benefits. 7 (4): 216–24. PMC 4105729. PMID 25126373.

- ^ "Counterfeit Drugs Questions and Answers" FDA

- ^ "Counterfeit drugs raise Africa’s temperature", AfricaRenewal, U.N., May 2013

- ^ "Interpol: Raids in 36 countries yield $25M in fake goods", Seattle Times, July 12, 2018

- ^ "Poison pills" Economist magazine, September 2, 2010

- ^ "News Releases" Archived February 20, 2011, at the Wayback Machine U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, January 15, 2009

- ^ "Customs seize Chinese cargo with fake 'made-in-India' products", The Times of India, July 17, 2009

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on October 22, 2018. Retrieved June 28, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Food Fraud and "Economically Motivated Adulteration" of Food and Food Ingredients". Congressional Research Service. January 10, 2014. Retrieved January 19, 2020.

- ^ Larson, Sarah (September 4, 2023). "The Lies in Your Grocery Store". The New Yorker. Retrieved April 29, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Jeneen Interlandi (February 8, 2010). "The fake-food detectives". Newsweek. Archived from the original on October 21, 2010.

- ^ a b "Something fishy? Counterfeit foods enter the U.S. market" USA Today, January 23, 2009

- ^ "Oceana study reveals seafood fraud nationwide". Oceana. February 2013. Retrieved May 2, 2016.

- ^ "Oceana study reveals seafood fraud nationwide" (PDF). Oceana. February 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 9, 2017. Retrieved May 2, 2016.

- ^ "Globe investigation finds widespread seafood mislabeling".

- ^ Pulkkinen, Levi (July 19, 2019). "Fraudsters convicted for selling spoiled, tainted food to discount grocer". crosscut.com. Cascade PBS News.

- ^ Abel, David (March 16, 2015). "US aims to curb seafood fraud". Boston Globe.

- ^ "Counterfeit food a 'serious threat' says EC" MeatProcess.com, November 13, 2006

- ^ a b "Food frauds - Intention, detection and management" (PDF). Food safety toolkit for Asia and the Pacific. Vol. 5. Bangkok: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). 2021. Retrieved April 17, 2024.

- ^ a b "Fake makeup can be an easy buy – and a health hazard", CBS, December 6, 2017

- ^ "Illicit cigarette tracking and the financing of organized crime". Police Chief magazine. 2004. Archived from the original on December 20, 2005. Retrieved July 31, 2014.

- ^ "Smoke and mirrors in Turkey with illicit cigarette trade". Thenational.ae. Retrieved July 21, 2014.

- ^ "Counterfeit Chinese Parts Slipping Into U.S. Military Aircraft: Report", ABC News, May 22, 2012

- ^ "Senate Armed Services Committee Releases Report on Counterfeit Electronic Parts" Archived June 1, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, U.S. Senate Armed Services Committee Report, May 21, 2012

- ^ "Lincoln Han - Counterfeits, fake goods, intellectual property and infringement aware". www.1000uf.com. Archived from the original on May 8, 2021. Retrieved March 26, 2022.

- ^ "U.S. Shutters 82 Sites in Crackdown on Downloads, Counterfeit Goods" Wired magazine, November 29, 2010

- ^ "Federal Courts Order Seizure of 82 Website Domains" U.S. Dept. of Justice Press Release, November 29, 2010

- ^ "French warning on counterfeits: don't sell 'em, don't buy 'em" Archived September 3, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Applied DNA Sciences, May 3, 2011

- ^ "European Anti-Counterfeiting Network". REACT. Retrieved January 17, 2014.

- ^ "Counterfeit Luxury: Feds Bust Largest-Ever Counterfeit Smuggling Ring." Archived May 5, 2011, at the Wayback Machine Second City Style, December 6, 2007

- ^ "U.S. Customs and Border Protection Intellectual Property Rights e-Recordation Application" (PDF). U.S. Customs and Border Protection. 2006. Retrieved February 11, 2010.

- ^ Curry, Sheree (May 13, 1996). "Farewell, My Logo: A Detective Story - Counterfeiting Name Brands is Shaping Up as the Crime of the 21st Century. It Costs U.S. Companies $200 Billion a Year". Fortune. Retrieved February 11, 2010.

- ^ "Obama Administration Responds to We the People Petitions on SOPA and Online Piracy", The White House Blog, January 14, 2012

- ^ "SOPA author withdraws controversial anti-piracy bill". Memeburn.com. January 23, 2012. Retrieved January 17, 2014.

- ^ LaFraniere, Sharon (March 1, 2009). "Facing Counterfeiting Crackdown, Beijing Vendors Fight Back". The New York Times. Retrieved March 2, 2009.

- ^ a b c d Zhang, Angela Huyue (2024). High Wire: How China Regulates Big Tech and Governs Its Economy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780197682258.

- ^ "Anti-counterfeiting agreement signed in Tokyo", Reuters, October 1, 2011

- ^ "ACTA is worthless without Chinese involvement", The Inquirer, October 7, 2010

- ^ "EU defends final Acta text on counterfeiting", EUObserver.com, October 7, 2010

- ^ "Counterfeit drugs making nonsense of medical practice in Nigeria" Archived July 21, 2012, at archive.today, Nigerian Health Journal, July 16, 2011

- ^ "Interpol seizes 25 mln USD fake goods in worldwide operations", China.org, July 13, 2018

- ^ "Counterfeiting: Many Risks and Many Victims", CNBC, July 13, 2010

- ^ "Garment Sweatshops in Argentina an Open Secret", Inter Press Service, May 30, 2015

- ^ Thomas, Dana. Deluxe: How Luxury Lost Its Luster, Penguin (2007) p. 288

- ^ a b Felix, Antonia. Sonia Sotomayor: The True American Dream, Penguin (2010) e-book

- ^ "Counterfeit goods are linked to terror groups - Business - International Herald Tribune". The New York Times. February 12, 2007.

- ^ Borunda, Daniel (April 19, 2012). "Mexican drug cartels tap counterfeit market". El Paso Times. Archived from the original on September 13, 2012. Retrieved January 17, 2014.

- ^ "According to the Spanish authorities, cases involving counterfeit products are often linked to the organisation of illegal immigration" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on April 10, 2011. Retrieved June 3, 2009.

- ^ "Counterfeit goods fund violent gang activity | abc7.com". Abclocal.go.com. June 10, 2010. Archived from the original on August 11, 2012. Retrieved January 17, 2014.

- ^ "MSU LAUNCHES FIRST ANTI-COUNTERFEITING RESEARCH PROGRAM", MSU Today, Michigan State University, February 8, 2010

- ^ "Nowotarski, Mark, "The Power of Policing Trademarks and Design Patents", IPWatchdog, 25 September 2013". Ipwatchdog.com. September 25, 2013. Retrieved August 24, 2014.

- ^ Harris, Dan (April 21, 2013). "Harris, Dan, "How to Stop China Counterfeiting, Or At Least Reduce It", ChinaLawBlog, 21 April 2013". Chinalawblog.com. Retrieved August 24, 2014.

- ^ Share and share alike: the challenges from social media for intellectual property rights. UK Government: Intellectual Property Office. 2017. pp. 1–150. ISBN 978-1-910790-30-4.

- ^ Stroppa, Andrea (2016). "Social media and luxury goods counterfeit: a growing concern for government, industry and consumers worldwide". The Washington Post. Washington, D.C. pp. 1–50.

- ^ "That Chanel bag on your Instagram feed may be fake". azcentral. Retrieved October 28, 2017.

- ^ "New trends in online counterfeiting require updated enforcement policies - World Trademark Review". www.worldtrademarkreview.com. Retrieved October 28, 2017.

- ^ How Anti-shoplifting Devices Work", HowStuffWorks.com

- ^ a b Müller, Christian; Garriga, M.; Campoy-Quiles, M. (2012). "Patterned optical anisotropy in woven conjugated polymer systems". Applied Physics Letters. 101 (17): 171907. Bibcode:2012ApPhL.101q1907M. doi:10.1063/1.4764518.

Further reading

[edit]- Sara R. Ellis, Copyrighting Couture: An Examination of Fashion Design Protection and Why the DPPA and IDPPPA are a Step Towards the Solution to Counterfeit Chic, 78 Tenn. L. Rev. 163 (2010).

- Phillips, Tim. Knockoff: The Deadly Trade in Counterfeit Goods Kogan Page, U.K. (2006)

- Wilson, Bee. Swindled: The Dark History of Food Fraud, from Poisoned Candy to Counterfeit Coffee, Princeton University Press (2008)

- Ellis, D.I., Brewster, V.L., Dunn, W.B., Allwood, J.W., Golovanov, A. and Goodacre, R. (2012) Fingerprinting food: current technologies for the detection of food adulteration and contamination. Chemical Society Reviews, 41, 5706–5727. doi:10.1039/c2cs35138b

- Ellis, D.I., Muhamadali, H., Haughey, S.A., Elliott, C.T. and Goodacre, R. (2015) Point-and-shoot: rapid quantitative detection methods for on-site food fraud analysis – moving out of the laboratory and into the food supply chain. Analytical Methods. 7, 9401–9414. doi:10.1039/C5AY02048D

- Ellis, D.I.; Eccles, R.; Xu, Y.; Griffen, J.; Muhamadali, H.; Matousek, P.; Goodall, I.; Goodacre, R. (2017). "Through-container, extremely low concentration detection of multiple chemical markers of counterfeit alcohol using a handheld SORS device". Scientific Reports. 7 (1): 12082. Bibcode:2017NatSR...712082E. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-12263-0. PMC 5608898. PMID 28935907.

- Share and share alike: the challenges from social media for intellectual property rights. UK Government: Intellectual Property Office. 2017. 99. 1–150. ISBN 978-1-910790-30-4.

- Stroppa, A., & Stefano, D. D. (2016). Social media and luxury goods counterfeit: a growing concern for government, industry and consumers worldwide (pp. 1–50, Rep.) (B. Parrella, Ed.). Washington, D.C.: The Washington Post.