Carvedilol

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Coreg, others |

| Other names | BM-14190 |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a697042 |

| License data |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 25–35% |

| Protein binding | 98% |

| Metabolism | Liver (CYP2D6, CYP2C9) |

| Elimination half-life | 7–10 hours |

| Excretion | Urine (16%), feces (60%) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| PDB ligand | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.117.236 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

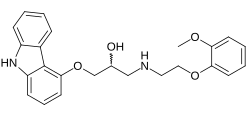

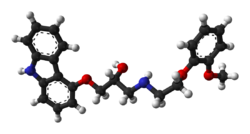

| Formula | C24H26N2O4 |

| Molar mass | 406.482 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Chirality | Racemic mixture |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Carvedilol, sold under the brand name Coreg among others, is a beta blocker medication, that may be prescribed for the treatment of high blood pressure (hypertension) and chronic heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (also known as HFrEF or systolic heart failure).[1][2] Beta-blockers as a collective medication class are not recommended as routine first-line treatment of high blood pressure for all patients, due to evidence demonstrating less effective cardiovascular protection and a less favourable safety profile when compared to other classes of blood pressure-lowering medications.[1][3][4]

Common side effects include dizziness, tiredness, joint pain, low blood pressure, nausea, and shortness of breath.[5] Severe side effects may include bronchospasm.[5] Safety during pregnancy or breastfeeding is unclear.[6] Use is not recommended in those with liver problems.[7] Carvedilol is a nonselective beta blocker and alpha-1 blocker.[5] How it improves outcomes is not entirely clear but may involve dilation of blood vessels.[5]

Carvedilol was patented in 1978 and approved for medical use in the United States in 1995.[5][8] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[9] It is available as a generic medication.[5] In 2022, it was the 34th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 17 million prescriptions.[10][11]

Medical uses

[edit]Carvedilol is indicated in the management of congestive heart failure (CHF), commonly as an adjunct to angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor (ACE inhibitors) and diuretics. It has been clinically shown to reduce mortality and hospitalizations in people with CHF.[12] The mechanism of carvedilol in heart failure is due to its inhibition of receptors in the adrenergic nervous system, which releases noradrenaline to the body, including the heart.[13] Noradrenaline is a hormone that causes the heart to beat faster and work harder.[13] Blocking its binding to adrenergic receptors in the heart causes vasodilation, decreases heart rate and blood pressure, and improves myocardial contractility,[14] which ultimately decreases the heart's workload.[13]

Carvedilol reduces the risk of death, hospitalisations, and recurring heart attacks in patients with moderate to severe heart failure (with an ejection fraction <40%) following a heart attack [15][16][17] Carvedilol has also been proven to reduce death and hospitalization in patients with severe heart failure.[18]

Carvedilol is not considered a first-line treatment for hypertension; however, research has demonstrated that it exhibits an antihypertensive effect when compared to a placebo or other antihypertensive medications.[19][20]

Carvedilol has shown efficacy in preventing bleeding from oesophageal varices in patients with mild to moderate cirrhosis and may have benefit in avoiding successive bleeds.[21][22]

Carvedilol is used in the treatment of acute cardiovascular toxicity (e.g. overdose) with sympathomimetics, for instance caused by amphetamine, methamphetamine, cocaine, or ephedrine.[23][24] It has also specifically been found to block the sympathomimetic effects of MDMA.[25][23][26] Dual α1 and beta blockers like carvedilol and labetalol may be more favorable for such purposes due to the possibility of "unopposed α-stimulation" with selective beta blockers.[23]

Available forms

[edit]Carvedilol is available in the following forms:

Contraindications

[edit]Carvedilol should not be used in patients with bronchial asthma or bronchospastic conditions due to increased risk of bronchoconstriction.[29][30] It should not be used in people with second- or third-degree atrioventricular block, sick sinus syndrome, severe bradycardia (unless a permanent pacemaker is in place), or a decompensated heart condition. People with severe hepatic impairment should use carvedilol with caution.[31][32][33]

Side effects

[edit]The most common side effects (>10% incidence) of carvedilol include:[27]

- Dizziness

- Fatigue

- Low blood pressure

- Diarrhea

- Weakness

- Slowed heart rate

- Weight gain

- Erectile dysfunction

Carvedilol is not recommended for people with uncontrolled bronchospastic disease (e.g. current asthma symptoms) as it can block receptors that assist in opening the airways.[27]

Carvedilol may mask symptoms of low blood sugar,[27] resulting in hypoglycemia unawareness. This is termed beta blocker induced hypoglycemia unawareness.

Interactions

[edit]The risk of bradycardia is increased if used with amiodarone, digoxin, diltiazem, ivabradine, or verapamil.[34] Also, combination of carvedilol with non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, including diltiazem and verapamil, enhances it cardiodepressant effects.[34]

Pharmacology

[edit]Pharmacodynamics

[edit]| Site | Ki (nM) | Action |

|---|---|---|

| 5-HT1A | 3.4 | Antagonist |

| 5-HT2 | 207 | Antagonist |

| D2 | 213 | Antagonist |

| α1 | 3.4 | Antagonist |

| α2 | 2,168 | Antagonist |

| β1 | 0.24–0.43 | Antagonist |

| β2 | 0.19–0.25 | Antagonist |

| M2 | ? | Antagonist[35] |

Carvedilol is both a non-selective β-adrenergic receptor antagonist (β1, β2) and an α-adrenergic receptor antagonist (α1). The S(–) enantiomer accounts for the beta-blocking activity whereas the S(–) and R(+) enantiomers have alpha-blocking activity.[27] The affinity (Ki) of carvedilol for the β-adrenergic receptors is 0.32 nM for the human β1-adrenergic receptor and 0.13 to 0.40 nM for the β2-adrenergic receptor.[36]

Using rat proteins, carvedilol has shown affinity for a variety of targets including the β1-adrenergic receptor (Ki = 0.24–0.43 nM), β2-adrenergic receptor (Ki = 0.19–0.25 nM), α1-adrenergic receptor (Ki = 3.4 nM), α2-adrenergic receptor (Ki = 2,168 nM), 5-HT1A receptor (Ki = 3.4 nM), 5-HT2 receptor (Ki = 207 nM), H1 receptor (Ki = 3,034 nM), D2 receptor (Ki = 213 nM), μ-opioid receptor (Ki = 2,700 nM), veratridine site of voltage-gated sodium channels (IC50 = 1,260 nM), serotonin transporter (Ki = 528 nM), norepinephrine transporter (Ki = 2,406 nM), and dopamine transporter (Ki = 627 nM).[37] It is an antagonist of the human 5-HT2A receptors with moderate affinity (Ki = 547 nM), although it is unclear if this is significant for its pharmacological actions given its much stronger activity at adrenergic receptors.[38]

Carvedilol reversibly binds to β-adrenergic receptors on cardiac myocytes. Inhibition of these receptors prevents a response to the sympathetic nervous system, leading to decreased heart rate and contractility. This action is beneficial in heart failure patients where the sympathetic nervous system is activated as a compensatory mechanism.[39] Carvedilol blockade of α1-adrenergic receptors causes vasodilation of blood vessels. This inhibition leads to decreased peripheral vascular resistance and an antihypertensive effect. There is no reflex tachycardia response due to carvedilol blockade of β1-adrenergic receptors on the heart.[40]

Pharmacokinetics

[edit]Carvedilol is about 25% to 35% bioavailable following oral administration due to extensive first-pass metabolism. Absorption is slowed when administered with food, however, it does not show a significant difference in bioavailability. Taking carvedilol with food decreases the risk of orthostatic hypotension.[27]

The majority of carvedilol is bound to plasma proteins (98%), mainly to albumin. Carvedilol is a basic, hydrophobic compound with a steady-state volume of distribution of 115 L. Plasma clearance ranges from 500 to 700 mL/min.[27] Carvedilol is highly lipophilic and easily crosses the blood–brain barrier in animals, and hence is not thought to be peripherally selective.[41][42]

The compound is metabolized by liver enzymes, CYP2D6 and CYP2C9 via aromatic ring oxidation and glucuronidation, then further conjugated by glucuronidation and sulfation. The three active metabolites exhibit only one-tenth of the vasodilating effect of the parent compound. However, the 4'-hydroxyphenyl metabolite is about 13-fold more potent in β-blockade than the parent.[27]

The mean elimination half-life of carvedilol following oral administration ranges from 7 to 10 hours. The pharmaceutical product is a mix of two enantiomorphs, R(+)-carvedilol and S(–)-carvedilol, with differing metabolic properties. R(+)-Carvedilol undergoes preferential selection for metabolism, which results in a fractional half-life of about 5 to 9 hours, compared with 7 to 11 hours for the S(-)-carvedilol fraction.[27]

Chemistry

[edit]Carvedilol is a highly lipophilic compound with an experimental log P of 3.8 to 4.19 and a predicted log P of 3.05 to 4.2.[43][44][45][46][47]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Mancia G, Kreutz R, Brunström M, Burnier M, Grassi G, Januszewicz A, et al. (December 2023). "2023 ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension: Endorsed by the International Society of Hypertension (ISH) and the European Renal Association (ERA)". Journal of Hypertension. 41 (12): 1874–2071. doi:10.1097/HJH.0000000000003480. hdl:11379/603005. PMID 37345492.

- ^ McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, Gardner RS, Baumbach A, Böhm M, et al. (September 2021). "2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure". European Heart Journal. 42 (36): 3599–3726. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehab368. PMID 34447992.

- ^ Wei J, Galaviz KI, Kowalski AJ, Magee MJ, Haw JS, Narayan KM, et al. (February 2020). "Comparison of Cardiovascular Events Among Users of Different Classes of Antihypertension Medications: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis". JAMA Network Open. 3 (2): e1921618. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.21618. PMC 7043193. PMID 32083689.

- ^ Bangalore S, Parkar S, Grossman E, Messerli FH (October 2007). "A meta-analysis of 94,492 patients with hypertension treated with beta blockers to determine the risk of new-onset diabetes mellitus". The American Journal of Cardiology. 100 (8): 1254–1262. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.05.057. PMID 17920367.

- ^ a b c d e f "Carvedilol Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. AHFS. Retrieved 24 December 2018.

- ^ "Carvedilol Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. Retrieved 24 December 2018.

- ^ British national formulary : BNF 76 (76 ed.). Pharmaceutical Press. 2018. p. 147. ISBN 9780857113382.

- ^ Fischer J, Ganellin CR (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 463. ISBN 9783527607495.

- ^ World Health Organization (2023). The selection and use of essential medicines 2023: web annex A: World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 23rd list (2023). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/371090. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2023.02.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2022". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 30 August 2024. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ "Carvedilol Drug Usage Statistics, United States, 2013 - 2022". ClinCalc. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE, Drazner MH, et al. (American College of Cardiology Foundation; American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines) (15 October 2013). "2013 AHA Guidelines for the Management of Heart Failure" (PDF). Circulation. 128 (16): e240-327. doi:10.1161/CIR.0b013e31829e8776. PMID 23741058.

- ^ a b c Ogbru O (4 November 2022). Shiel Jr WC (ed.). "carvedilol (Coreg): Heart Failure, Side Effects, Uses & Dosage". MedicineNet. Retrieved 1 May 2024.

- ^ Kubon C, Mistry NB, Grundvold I, Halvorsen S, Kjeldsen SE, Westheim AS (April 2011). "The role of beta-blockers in the treatment of chronic heart failure". Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 32 (4): 206–212. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2011.01.006. PMID 21376403.

- ^ Dargie HJ (May 2001). "Effect of carvedilol on outcome after myocardial infarction in patients with left-ventricular dysfunction: the CAPRICORN randomised trial". Lancet. 357 (9266): 1385–1390. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(00)04560-8. PMID 11356434. S2CID 1840228.

- ^ Huang BT, Huang FY, Zuo ZL, Liao YB, Heng Y, Wang PJ, et al. (June 2015). "Meta-Analysis of Relation Between Oral β-Blocker Therapy and Outcomes in Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction Who Underwent Percutaneous Coronary Intervention". The American Journal of Cardiology. 115 (11): 1529–1538. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.02.057. PMID 25862157.

- ^ Packer M, Fowler MB, Roecker EB, Coats AJ, Katus HA, Krum H, et al. (October 2002). "Effect of carvedilol on the morbidity of patients with severe chronic heart failure: results of the carvedilol prospective randomized cumulative survival (COPERNICUS) study". Circulation. 106 (17): 2194–9. doi:10.1161/01.cir.0000035653.72855.bf. PMID 12390947.

- ^ Cleland JG, Bunting KV, Flather MD, Altman DG, Holmes J, Coats AJ, et al. (January 2018). "Beta-blockers for heart failure with reduced, mid-range, and preserved ejection fraction: an individual patient-level analysis of double-blind randomized trials". European Heart Journal. 39 (1): 26–35. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehx564. PMC 5837435. PMID 29040525.

- ^ Weber MA, Sica DA, Tarka EA, Iyengar M, Fleck R, Bakris GL (October 2006). "Controlled-release carvedilol in the treatment of essential hypertension". The American Journal of Cardiology. 98 (7A): 32L – 38L. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.07.017. PMID 17023230.

- ^ Saul SM, Duprez DA, Zhong W, Grandits GA, Cohn JN (June 2013). "Effect of carvedilol, lisinopril and their combination on vascular and cardiac health in patients with borderline blood pressure: the DETECT Study". Journal of Human Hypertension. 27 (6): 362–367. doi:10.1038/jhh.2012.54. PMID 23190794.

- ^ Reiberger T, Ulbrich G, Ferlitsch A, Payer BA, Schwabl P, Pinter M, et al. (November 2013). "Carvedilol for primary prophylaxis of variceal bleeding in cirrhotic patients with haemodynamic non-response to propranolol". Gut. 62 (11): 1634–1641. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2012-304038. PMID 23250049.

- ^ Jachs M, Hartl L, Simbrunner B, Bauer D, Paternostro R, Balcar L, et al. (August 2023). "Carvedilol Achieves Higher Hemodynamic Response and Lower Rebleeding Rates Than Propranolol in Secondary Prophylaxis". Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 21 (9): 2318–2326.e7. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2022.06.007. PMID 35842118.

- ^ a b c Richards JR, Albertson TE, Derlet RW, Lange RA, Olson KR, Horowitz BZ (May 2015). "Treatment of toxicity from amphetamines, related derivatives, and analogues: a systematic clinical review". Drug Alcohol Depend. 150: 1–13. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.01.040. PMID 25724076.

- ^ Richards JR, Hollander JE, Ramoska EA, Fareed FN, Sand IC, Izquierdo Gómez MM, et al. (May 2017). "β-Blockers, Cocaine, and the Unopposed α-Stimulation Phenomenon". J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 22 (3): 239–249. doi:10.1177/1074248416681644. PMID 28399647.

- ^ Fonseca DA, Ribeiro DM, Tapadas M, Cotrim MD (July 2021). "Ecstasy (3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine): Cardiovascular effects and mechanisms". Eur J Pharmacol. 903: 174156. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2021.174156. PMID 33971177.

- ^ Hysek C, Schmid Y, Rickli A, Simmler LD, Donzelli M, Grouzmann E, et al. (August 2012). "Carvedilol inhibits the cardiostimulant and thermogenic effects of MDMA in humans". Br J Pharmacol. 166 (8): 2277–2288. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.01936.x. PMC 3448893. PMID 22404145.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Coreg" (PDF). GlaxoSmithKline. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. April 2008.

- ^ "Drug Approval Package". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- ^ Morales DR, Lipworth BJ, Donnan PT, Jackson C, Guthrie B (January 2017). "Respiratory effect of beta-blockers in people with asthma and cardiovascular disease: population-based nested case control study". BMC Medicine. 15 (1): 18. doi:10.1186/s12916-017-0781-0. PMC 5270217. PMID 28126029.

- ^ Kotlyar E, Keogh AM, Macdonald PS, Arnold RH, McCaffrey DJ, Glanville AR (December 2002). "Tolerability of carvedilol in patients with heart failure and concomitant chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or asthma". The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation. 21 (12): 1290–5. doi:10.1016/s1053-2498(02)00459-x. PMID 12490274.

- ^ Sinha R, Lockman KA, Mallawaarachchi N, Robertson M, Plevris JN, Hayes PC (July 2017). "Carvedilol use is associated with improved survival in patients with liver cirrhosis and ascites" (PDF). Journal of Hepatology. 67 (1): 40–46. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2017.02.005. hdl:20.500.11820/7afe3b88-1064-4da1-927e-4d4e867387eb. PMID 28213164.

- ^ Zacharias AP, Jeyaraj R, Hobolth L, Bendtsen F, Gluud LL, Morgan MY (October 2018). "Carvedilol versus traditional, non-selective beta-blockers for adults with cirrhosis and gastroesophageal varices". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (10): CD011510. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011510.pub2. PMC 6517039. PMID 30372514.

- ^ Lo GH, Chen WC, Wang HM, Yu HC (November 2012). "Randomized, controlled trial of carvedilol versus nadolol plus isosorbide mononitrate for the prevention of variceal rebleeding". Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 27 (11): 1681–7. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1746.2012.07244.x. PMID 22849337. S2CID 23494154.

- ^ a b Koshman SL, Paterson I (15 March 2023). "Heart Failure". Canadian Pharmacists Association (CPS). Retrieved 29 April 2024.

- ^ Xu XL, Zang WJ, Lu J, Kang XQ, Li M, Yu XJ (December 2006). "Effects of carvedilol on M2 receptors and cholinesterase-positive nerves in adriamycin-induced rat failing heart". Autonomic Neuroscience. 130 (1–2): 6–16. doi:10.1016/j.autneu.2006.04.005. PMID 16798104. S2CID 22480332.

- ^ "Carvedilol | Ligand page". IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY.

- ^ Pauwels PJ, Gommeren W, Van Lommen G, Janssen PA, Leysen JE (December 1988). "The receptor binding profile of the new antihypertensive agent nebivolol and its stereoisomers compared with various beta-adrenergic blockers". Mol Pharmacol. 34 (6): 843–51. PMID 2462161.

- ^ Murnane KS, Guner OF, Bowen JP, Rambacher KM, Moniri NH, Murphy TJ, et al. (June 2019). "The adrenergic receptor antagonist carvedilol interacts with serotonin 2A receptors both in vitro and in vivo". Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 181: 37–45. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2019.04.003. PMC 6570414. PMID 30998954.

- ^ Manurung D, Trisnohadi HB (2007). "Beta blockers for congestive heart failure" (PDF). Acta Medica Indonesiana. 39 (1): 44–8. PMID 17297209. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ^ Ruffolo RR, Gellai M, Hieble JP, Willette RN, Nichols AJ (1990). "The pharmacology of carvedilol". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 38 (Suppl 2): S82 – S88. doi:10.1007/BF01409471. PMID 1974511. S2CID 2901620.

- ^ Wang J, Ono K, Dickstein DL, Arrieta-Cruz I, Zhao W, Qian X, et al. (December 2011). "Carvedilol as a potential novel agent for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease". Neurobiol Aging. 32 (12): 2321.e1–12. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.05.004. PMC 2966505. PMID 20579773.

- ^ Bart J, Dijkers EC, Wegman TD, de Vries EG, van der Graaf WT, Groen HJ, et al. (August 2005). "New positron emission tomography tracer [(11)C]carvedilol reveals P-glycoprotein modulation kinetics". Br J Pharmacol. 145 (8): 1045–51. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0706283. PMC 1576233. PMID 15951832.

- ^ "Carvedilol". PubChem. Retrieved 1 August 2024.

- ^ "Carvedilol: Uses, Interactions, Mechanism of Action". DrugBank Online. 14 September 1995. Retrieved 1 August 2024.

- ^ "Carvedilol". ChemSpider. 21 July 2022. Retrieved 1 August 2024.

- ^ "Human Metabolome Database: Showing metabocard for Carvedilol (HMDB0015267)". Human Metabolome Database. 6 September 2012. Retrieved 1 August 2024.

- ^ Siqueira Jørgensen S, Rades T, Mu H, Graeser K, Müllertz A (January 2019). "Exploring the utility of the Chasing Principle: influence of drug-free SNEDDS composition on solubilization of carvedilol, cinnarizine and R3040 in aqueous suspension". Acta Pharm Sin B. 9 (1): 194–201. doi:10.1016/j.apsb.2018.07.004. PMC 6361727. PMID 30766791.

Further reading

[edit]- Chakraborty S, Shukla D, Mishra B, Singh S (February 2010). "Clinical updates on carvedilol: a first choice beta-blocker in the treatment of cardiovascular diseases". Expert Opinion on Drug Metabolism & Toxicology. 6 (2): 237–50. doi:10.1517/17425250903540220. PMID 20073998. S2CID 25670550.

- Dean L (2018). "Carvedilol Therapy and CYP2D6 Genotype". In Pratt VM, McLeod HL, Rubinstein WS, et al. (eds.). Medical Genetics Summaries. National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). PMID 30067327. Bookshelf ID: NBK518573.