History of copyright

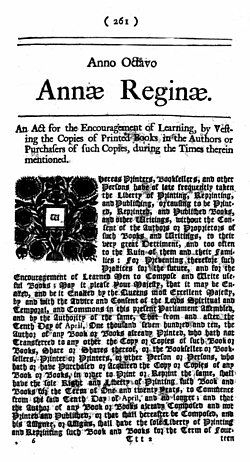

The history of copyright starts with early privileges and monopolies granted to printers of books. The British Statute of Anne 1710, full title "An Act for the Encouragement of Learning, by vesting the Copies of Printed Books in the Authors or purchasers of such Copies, during the Times therein mentioned", was the first copyright statute. Initially copyright law only applied to the copying of books. Over time other uses such as translations and derivative works were made subject to copyright and copyright now covers a wide range of works, including maps, performances, paintings, photographs, sound recordings, motion pictures and computer programs.

Today national copyright laws have been standardised to some extent through international and regional agreements such as the Berne Convention and the European copyright directives. Although there are consistencies among nations' copyright laws, each jurisdiction has separate and distinct laws and regulations about copyright. Some jurisdictions also recognize moral rights of creators, such as the right to be credited for the work.

Copyrights are exclusive rights granted to the author or creator of an original work, including the right to copy, distribute and adapt the work. Copyright does not protect ideas, only their expression or fixation. In most jurisdictions copyright arises upon fixation and does not need to be registered. Copyright owners have the exclusive statutory right to exercise control over copying and other exploitation of the works for a specific period of time, after which the work is said to enter the public domain. Uses which are covered under limitations and exceptions to copyright, such as fair use, do not require permission from the copyright owner. All other uses require permission and copyright owners can license or permanently transfer or assign their exclusive rights to others.

Early developments

[edit]

A possible historical case-law on the right to copy comes from ancient Ireland. The Cathach is the oldest extant Irish manuscript of the Psalter and the earliest example of Irish writing. It contains a Vulgate version of Psalms XXX (30) to CV (105) with an interpretative rubric or heading before each psalm. It is traditionally ascribed to Saint Columba as the copy, made at night in haste by a miraculous light, of a Psalter lent to Columba by St. Finnian. In the 6th century, a dispute arose about the ownership of the copy and King Diarmait Mac Cerbhaill gave the judgement "To every cow belongs her calf, therefore to every book belongs its copy."[1] The Battle of Cúl Dreimhne was said to be fought over this issue. However, the account of the dispute over the Cathach copy comes from a significantly later source and its validity has been questioned.[2]

Modern copyright law has been influenced by an array of older legal rights that have been recognized throughout history, including the moral rights of the author who created a work, the economic rights of a benefactor who paid to have a copy made, the property rights of the individual owner of a copy, and a sovereign's right to censor and to regulate the printing industry. The origins of some of these rights can be traced back to ancient Greek culture, ancient Jewish law, and ancient Roman law.[3] In Greek society, during the sixth century B.C.E., there emerged the notion of the individual self, including personal ideals, ambition, and creativity.[4] The individual self is important in copyright because it distinguishes the creativity produced by an individual from the rest of society.[citation needed] In ancient Jewish Talmudic law there can be found recognition of the moral rights of the author and the economic or property rights of an author.[5]

Prior to the invention of movable type in the West in the mid-15th century, texts were copied by hand and the small number of texts generated few occasions for these rights to be tested. During the Roman Empire, a period of prosperous book trade, no copyright or similar regulations existed,[6] copying by those other than professional booksellers was rare. This is because books were, typically, copied by literate slaves, who were expensive to buy and maintain. Thus, any copier would have had to pay much the same expense as a professional publisher. Roman book sellers would sometimes pay a well-regarded author for first access to a text for copying, but they had no exclusive rights to a work and authors were not normally paid anything for their work. Martial, in his Epigrams, complains about receiving no profit despite the popularity of his poetry throughout the Roman Empire.[6]

The printing press came into use in Europe in the 1400s and 1500s, and made it much cheaper to produce books.[citation needed] As there was initially no copyright law, anyone could buy or rent a press and print any text. Popular new works were immediately re-set and re-published by competitors, so printers needed a constant stream of new material. Fees paid to authors for new works were high, and significantly supplemented the incomes of many academics.[7]

Printing brought profound social changes. The rise in literacy across Europe led to a dramatic increase in the demand for reading matter.[8] Prices of reprints were low, so publications could be bought by poorer people, creating a mass-market readership.[7] In German-speaking areas, most publications were academic papers, and most were scientific and technical publications, often autodidactic practical instruction manuals on topics such as dike construction.[7] After copyright law became established (in 1710 in England, and in the 1840s in German-speaking areas) the low-price mass market vanished, and fewer, more expensive editions were published.[7][9] Heinrich Heine, in a 1854 letter to his publisher, complains: "Due to the tremendously high prices you have established, I will hardly see a second edition of the book anytime soon. But you must set lower prices, dear Campe, for otherwise I really don't see why I was so lenient with my material interests."[7]

Early privileges and monopolies

[edit]

The origin of copyright law in most European countries lies in efforts by the church and governments to regulate and control the output of printers.[10] Before the invention of the printing press, a writing, once created, could only be physically multiplied by the highly laborious and error-prone process of manual copying by scribes. An elaborate system of censorship and control over scribes did not exist, as scribes were scattered and worked on single manuscripts.[11] Printing allowed for multiple exact copies of a work, leading to a more rapid and widespread circulation of ideas and information (see print culture).[10] In 1559 the Index Expurgatorius, or List of Prohibited Books, was issued for the first time.[11]

In Europe printing was invented and widely established in the 15th and 16th centuries.[10] While governments and church encouraged printing in many ways, which allowed the dissemination of Bibles and government information, works of dissent and criticism could also circulate rapidly. As a consequence, governments established controls over printers across Europe, requiring them to have official licences to trade and produce books. The licenses typically gave printers the exclusive right to print particular works for a fixed period of years, and enabled the printer to prevent others from printing the same work during that period. The licenses could only grant rights to print in the territory of the state that had granted them, but they did usually prohibit the import of foreign printing.[10]

The republic of Venice granted its first privilege for a particular book in 1486. It was a special case, being the history of the city itself, the Rerum venetarum ab urbe condita opus of Marcus Antonius Coccius Sabellicus.[12] The second author in the world to achieve copyright, Royal printing privileges, was the humanist and grammarian Antonio de Nebrija, in Lexicon hoc est Dictionarium ex sermone latino in hispaniensem (Salamanca, 1492). From 1492 onwards Venice began regularly granting privileges for books.[13] The Republic of Venice, the dukes of Florence, and Leo X and other Popes conceded at different times to certain printers the exclusive privilege of printing for specific terms (rarely exceeding 14 years) editions of classic authors.[citation needed]

The first copyright privilege in England bears date 1518 and was issued to Richard Pynson, King's Printer, the successor to William Caxton. The privilege gives a monopoly for the term of two years. The date is 15 years later than that of the first privilege issued in France. Early copyright privileges were called "monopolies," particularly during the reign of Queen Elizabeth, who frequently gave grants of monopolies in articles of common use, such as salt, leather, coal, soap, cards, beer, and wine. The practice was continued until the Statute of Monopolies was enacted in 1623, ending most monopolies, with certain exceptions, such as patents; after 1623, grants of letters patent to publishers became common.[14]

The earliest German privilege of which there is trustworthy record was issued in 1501 by the Aulic Council to an association entitled the Sodalitas Rhenana Celtica, for the publication of an edition of the dramas of Hroswitha of Gandersheim, which had been prepared for the press by Conrad Celtes .[15] According to historian Eckhard Höffner indicated that there was no effective copyright legislation in Germany in the early 19th century.[16] Prussia introduced a copyright law in 1837, but even then authors and publishers just had to go to another German state to circumvent its ruling.[16]

As the "menace" of printing spread, governments established centralized control mechanisms,[17] and in 1557 the English Crown thought to stem the flow of seditious and heretical books by chartering the Stationers' Company. The right to print was limited to the members of that guild, and thirty years later the Star Chamber was chartered to curtail the "greate enormities and abuses" of "dyvers contentyous and disorderlye persons professinge the arte or mystere of pryntinge or selling of books." The right to print was restricted to two universities and to the 21 existing printers in the city of London, which had 53 printing presses. The French crown also repressed printing, and printer Etienne Dolet was burned at the stake in 1546. As the English took control of type founding in 1637, printers fled to the Netherlands. Confrontation with authority made printers radical and rebellious, and 800 authors, printers and book dealers were incarcerated in the Bastille before it was stormed in 1789.[17] The notion that the expression of dissent or subversive views should be tolerated, not censured or punished by law, developed alongside the rise of printing and the press. The Areopagitica, published in 1644 under the full title Areopagitica: A speech of Mr. John Milton for the liberty of unlicensed printing to the Parliament of England, was John Milton's response to the English parliament re-introducing government licensing of printers, hence publishers. In doing so Milton articulated the main strands of future discussions about freedom of expression. By defining the scope of freedom of expression and of "harmful" speech Milton argued against the principle of pre-censorship and in favour of tolerance for a wide range of views.[18]

Early British copyright law

[edit]

In England the printers, known as stationers, formed a collective organisation, known as the Stationers' Company. In the 16th century, the Stationers' Company was given the power to require all lawfully printed books to be entered into its register. Only members of the Stationers' Company could enter books into the register. This meant that the Stationers' Company achieved a dominant position over publishing in 17th-century England (no equivalent arrangement formed in Scotland and Ireland). The monopoly came to an end in 1695, when the English Parliament did not renew the Stationers' Company's power.[10]

In 1707, the parliaments of England and Scotland were united as a result of the Anglo-Scottish Union. The new parliament was able to change the laws in both countries and an important early piece of legislation was the Copyright Act 1710, also known as the Statute of Anne, after Queen Anne. The act came into force in 1710 and was the first copyright statute. Its full title was "An Act for the Encouragement of Learning, by vesting the Copies of Printed Books in the Authors or purchasers of such Copies, during the Times therein mentioned".[10]

The enforcement of the Statute of Anne in April 1710 marked a historic moment in the development of copyright law. As the world's first copyright statute it granted publishers of a book legal protection of 14 years with the commencement of the statute. It also granted 21 years of protection for any book already in print.[19] The Statute of Anne had a much broader social focus and remit than the monopoly granted to the Stationers' Company. The statute was concerned with the reading public, the continued production of useful literature, and the advancement and spread of education. The central plank of the statute is a social quid pro quo; to encourage "learned men to compose and write useful books" the statute guaranteed the finite right to print and reprint those works. It established a pragmatic bargain involving authors, the booksellers and the public.[20] The Statute of Anne ended the old system whereby only literature that met the censorship standards administered by the booksellers could appear in print. The statute furthermore created a public domain for literature, as previously all literature belonged to the booksellers forever.[21]

According to Patterson and Lindberg, the Statute of Anne:[21]

... transformed the stationers' copyright - which had been used as a device of monopoly and an instrument of censorship – into a trade-regulation concept to promote learning and to curtail the monopoly of publishers ... The features of the Statute of Anne that justify the epithet of trade regulation included the limited term of copyright, the availability of copyright to anyone, and the price-control provisions. Copyright, rather than being perpetual, was now limited to a term of fourteen years, with a like renewal term being available only to the author (and only if the author were living at the end of the first term).

When the statutory copyright term provided for by the Statute of Anne began to expire in 1731, London booksellers thought to defend their dominant position by seeking injunctions from the Court of Chancery for works by authors that fell outside the statute's protection. At the same time, the London booksellers lobbied parliament to extend the copyright term provided by the Statute of Anne. Eventually, in a case known as Midwinter v Hamilton (1743–1748), the London booksellers turned to common law and started a 30-year period known as the "battle of the booksellers", with London booksellers locking horns with the newly emerging Scottish book trade over the right to reprint works falling outside the protection of the Statute of Anne. The Scottish booksellers argued that no common law copyright existed in an author's work. The London booksellers argued that the Statute of Anne only supplemented and supported a pre-existing common law copyright. The dispute was argued out in a number of notable cases, including Millar v Kincaid (1749–1751) and Tonson v Collins (1761–1762).[22]

Common law copyright

[edit]A debate raged on whether printed ideas could be owned and London booksellers and other supporters of perpetual copyright argued that without it scholarship would cease to exist and that authors would have no incentive to continue creating works of enduring value if they could not bequeath the property rights to their descendants. Opponents of perpetual copyright argued that it amounted to a monopoly, which inflated the price of books, making them less affordable and therefore prevented the spread of the Enlightenment. London booksellers were attacked for using rights of authors to mask their greed and self-interest in controlling the book trade.[23][24] When Donaldson v Beckett reached the House of Lords in 1774, Lord Camden was most strident in his rejection of common law copyright, warning the Lords that, should they vote in favour of common law copyright, effectively a perpetual copyright, "all our learning will be locked up in the hands of the Tonsons and the Lintots of the age". Moreover, he warned, booksellers would then set upon books whatever price they pleased "till the public became as much their slaves, as their own hackney compilers are". He declared that "Knowledge and science are not things to be bound in such cobweb chains."[25]

In its ruling, the House of Lords established that the rights and responsibilities in copyright were determined by legislation.[26] There is, however, still disagreement over whether the House of Lords affirmed the existence of common-law copyright before it was superseded by the Statute of Anne. The Lords had traditionally been hostile to the booksellers' monopoly and were aware of how the doctrine of common law copyright, promoted by the booksellers, was used to support their case for a perpetual copyright. The Lords clearly decided against perpetual copyright[27] and, by confirming that the copyright term (the length of time that a work is in copyright) did expire according to statute, the Lords also affirmed the public domain. The ruling in Donaldson v Beckett confirmed that a large number of works and books first published in Britain were in the public domain, either because the copyright term granted by statute had expired or because they were first published before the Statute of Anne was enacted in 1710. This opened the market for cheap reprints of works by Shakespeare, Milton and Chaucer, works now considered classics. The expansion of the public domain in books broke the dominance of the London booksellers and allowed for competition, with the number of London booksellers and publishers rising nearly threefold, from 111 to 308, between 1772 and 1802.[28]

Eventually an understanding was established whereby authors had a pre-existing common-law copyright over their work, but that with the Statute of Anne parliament had limited these rights in order to strike a more appropriate balance between the interests of the author and the wider social good.[29] According to Patterson and Livingston, confusion about the nature of copyright has remained ever since. Copyright has come to be viewed both as a natural-law right of the author and as the statutory grant of a limited monopoly. One theory holds that copyright is created simply by the creation of a work, the other that it is owed to a copyright statute.[30]

In August 1906, The Copyright Law for Music Act 1906, known also as the T. P. O'Connor Bill, was added to copyright law when it was passed by the British Parliament, following many of the popular music writers at the time dying in poverty due to extensive piracy by gangs during the piracy crisis of sheet music in the early 20th century.[31][32][33][34] The gangs would buy a copy of the music at full price, copy it, and resell it, often at half the price from the original.[35]

Early French copyright law

[edit]

In pre-revolutionary France all books needed to be approved by official censors and authors and publishers had to obtain a royal privilege before a book could be published. Royal privileges were exclusive and usually granted for six years, with the possibility of renewal. Over time it was established that the owner of a royal privilege has the sole right to obtain a renewal indefinitely. In 1761 the Royal Council awarded a royal privilege to the heirs of an author rather than the author's publisher, sparking a national debate on the nature of literary property similar to that taking place in Britain during the battle of the booksellers.[36]

In 1777 a series of royal decrees reformed the royal privileges. The duration of privileges were set at a minimum duration of 10 years or the life of the author, which ever was longer. If the author obtained a privilege and did not transfer or sell it on, he could publish and sell copies of the book himself, and pass the privilege on to his heirs, who enjoyed an exclusive right into perpetuity. If the privilege was sold to a publisher, the exclusive right would only last the specified duration. The royal decrees prohibited the renewal of privileges and once the privilege had expired anyone could obtain a "permission simple" to print or sell copies of the work. Hence the public domain in books whose privilege had expired was expressly recognised.[36]

After the French Revolution a dispute over Comédie-Française being granted the exclusive right to the public performance of all dramatic works erupted and in 1791 the National Assembly abolished the privilege. Anyone was allowed to establish a public theatre and the National Assembly declared that the works of any author who had died more than five years ago were public property. In the same degree the National Assembly granted authors the exclusive right to authorise the public performance of their works during their lifetime, and extended that right to the authors' heirs and assignees for five years after the author's death. The National Assembly took the view that a published work was by its nature a public property, and that an author's rights are recognised as an exception to this principle, to compensate an author for his work.[36]

In 1793 a new law was passed giving authors, composers, and artists the exclusive right to sell and distribute their works, and the right was extended to their heirs and assigns for 10 years after the author's death. The National Assembly placed this law firmly on a natural right footing, calling the law the "Declaration of the Rights of Genius" and so evoking the famous Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. However, author's rights were subject to the condition of making depositing copies of the work with the Bibliothèque Nationale and 19th-century commentators characterised the 1793 law as utilitarian and "a charitable grant from society".[36]

Early United States copyright law

[edit]

The Statute of Anne did not apply to the American colonies. The economy of early America was largely agrarian and only three private copyright acts had been passed in America prior to 1783. Two of the acts were limited to seven years, the other was limited to a term of five years. In 1783 several authors' petitions persuaded the Continental Congress "that nothing is more properly a man's own than the fruit of his study, and that the protection and security of literary property would greatly tend to encourage genius and to promote useful discoveries." But under the Articles of Confederation, the Continental Congress had no authority to enact copyright law. The Continental Congress passed a resolution urging the States to "secure to the authors or publishers of any new book not hitherto printed ... the copy right of such books for a certain time not less than fourteen years from the first publication; and to secure to the said authors, if they shall survive the term first mentioned, ... the copy right of such books for another term of time no less than fourteen years.[37] Three states had already enacted copyright statutes in 1783 prior to the Continental Congress resolution, and in the subsequent three years all of the remaining states except Delaware passed a copyright statute. Seven of the States followed the Statute of Anne and the Continental Congress' resolution by providing two fourteen-year terms. The five remaining States granted copyright for single terms of fourteen, twenty and twenty one years, with no right of renewal.[38]

At the Philadelphia Convention in 1787, both James Madison of Virginia and Charles Cotesworth Pinckney of South Carolina submitted proposals that would allow Congress the power to grant copyright for a limited time. These proposals are the origin of the Copyright Clause in the United States Constitution, which allows the granting of copyright and patents for a limited time to serve a utilitarian function, namely "to promote the progress of science and useful arts". The first federal copyright act was the Copyright Act of 1790. It granted copyright for a term of 14 years "from the time of recording the title thereof" with a right of renewal for another 14 years if the author survived to the end of the first term. The act covered not only books, but also maps and charts. Only works both printed within the United States and created by citizens were eligible. With exception of the provision on maps and charts the Copyright Act of 1790 is copied almost verbatim from the Statute of Anne.[38]

At the time works only received protection under federal statutory copyright if the statutory formalities, such as a proper copyright notice, were satisfied. If this was not the case the work immediately entered into the public domain. In 1834 the Supreme Court ruled in Wheaton v. Peters (a case similar to the 1774 case of Donaldson v Beckett in Britain) that although the author of an unpublished work had a common law right to control the first publication of that work, the author did not have a common law right to control reproduction following the first publication of the work.[38]

Early internationalisation

[edit]

The Berne Convention was first established in 1886, and was subsequently re-negotiated in 1896 (Paris), 1908 (Berlin), 1928 (Rome), 1948 (Brussels), 1967 (Stockholm) and 1971 (Paris). The convention relates to literary and artistic works, which includes films, and the convention requires its member states to provide protection for every production in the literary, scientific and artistic domain. The Berne Convention has a number of core features, including the principle of national treatment, which holds that each member state to the convention would give citizens of other member states the same rights of copyright that it gave to its own citizens (Article 3-5).[39]

Another core feature is the establishment of minimum standards of national copyright legislation in that each member state agrees to certain basic rules which their national laws must contain. Though member states can if they wish increase the amount of protection given to copyright owners. One important minimum rule was that the term of copyright was to be a minimum of the author's lifetime plus 50 years. Another important minimum rule established by the Berne Convention is that copyright arises with the creation of a work and does not depend upon any formality such as a system of public registration (Article 5(2)). At the time some countries did require registration of copyright, and when Britain implemented the Berne Convention in the Copyright Act 1911 (1 & 2 Geo. 5. c. 46) it had to abolish its system of registration at Stationers' Hall.[39]

The Berne Convention focuses on authors as the key figure in copyright law and the stated purpose of the convention is "the protection of the rights of authors in their literary and artistic works" (Article 1), rather than the protection of publishers and other actors in the process of disseminating works to the public. In the 1928 revision the concept of moral rights was introduced (Article 6bis), giving authors the right to be identified as a such and to object to derogatory treatment of their works. These rights, unlike economic rights such as preventing reproduction, could not be transferred to others.[39]

The Berne Convention also enshrined limitations and exceptions to copyright, enabling the reproduction of literary and artistic works without the copyright owners prior permission. The detail of these exceptions was left to national copyright legislation, but the guiding principle is stated in Article 9 of the convention. The so-called three-step test holds that an exception is only permitted "in certain special cases, provided that such reproduction does not conflict with a normal exploitation of the work and does not unreasonably prejudice the legitimate interests of the author". Free use of copyrighted work is expressly permitted in the case of quotations from lawfully published works, illustration for teaching purposes, and news reporting (Article 10).[39]

Copyright in communist countries

[edit]Copyright and technology

[edit]- Digital technology introduces a new level of controversy into copyright policy.

- Inclusion of software as copyright subject matter on the recommendation of CONTU and then later with the EU Computer Programs Directive.

- Enactment of Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS).

- Controversy over the copyrightability of databases (Feist Publications v. Rural Telephone Service and contradictory cases); links to the debate over sui generis database rights.

- Enactment of the World Intellectual Property Organization Copyright Treaty; nations begin passing anti-circumvention laws.

Commentators such as Barlow (1994) have argued that digital copyright is fundamentally different and will remain persistently difficult to enforce; others such as Richard Stallman (1996)[40] have argued that the Internet deeply undermines the economic rationale for copyright in the first place. These perspectives may lead to the consideration of alternative compensation systems in place of exclusive rights for all types of information, including software, books, movies, and music.[41][42]

Expansions in scope and operation

[edit]- Move from common law and ad hoc grants of monopoly to copyright statutes.

- Expansions in subject matter (largely related to technology).

- Expansions on duration.

- Creation of new exclusive rights (such as performers' and other neighbouring rights).

- Creation of collecting societies.

- Criminalisation of copyright infringement.

- Creation of anti-circumvention laws.[43]

- Courts' application of secondary liability doctrines to cover file sharing networks

See also

[edit]- History of music piracy

- History of patent law

- Copyleft

- International copyright

- Copyright infringement

References

[edit]- ^ Royal Irish Academy. "The Cathach/The Psalter of St. Columba". Library Cathach. Archived from the original on 2014-07-02.

- ^ Lacey, Brian (2003). "The Battle of Cúl Dreimne: A Reassessment". The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland. 133: 78–85. ISSN 0035-9106.

- ^ Bettig, Ronald V. (1996). Copyrighting Culture: The Political Economy of Intellectual Property. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press. p. 11. ISBN 0-8133-1385-6.

- ^ Ploman, Edward W., and L. Clark Hamilton (1980). Copyright: Intellectual Property in the Information Age. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. p. 5. ISBN 0-7100-0539-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ploman, Edward W., and L. Clark Hamilton (1980). Copyright: Intellectual Property in the Information Age. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. p. 7. ISBN 0-7100-0539-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Martial, The Epigrams, Penguin, 1978, James Mitchie

- ^ a b c d e Thadeusz, Frank (18 August 2010). "No Copyright Law: The Real Reason for Germany's Industrial Expansion?". Spiegel Online.

- ^ Copyright in Historical Perspective, p. 136-137, Patterson, 1968, Vanderbilt Univ. Press

- ^ Lasar, Matthew (23 August 2010). "Did Weak Copyright Laws Help Germany Outpace The British Empire?". Wired.

- ^ a b c d e f MacQueen, Hector L; Charlotte Waelde; Graeme T Laurie (2007). Contemporary Intellectual Property: Law and Policy. Oxford University Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-19-926339-4.

- ^ a b de Sola Pool, Ithiel (1983). Technologies of freedom. Harvard University Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-674-87233-2.

- ^ Armstrong, Elizabeth. Before Copyright: the French book-privilege system 1498–1526. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge: 1990, p. 3

- ^ Armstrong, Elizabeth. Before Copyright: the French book-privilege system 1498–1526. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge: 1990, p. 6

- ^ Deazley, Ronan. Rethinking copyright: history, theory, language. (Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited, 2006), p. 24.

- ^ Kawohl, F. (2008) "Commentary on Imperial privileges for Conrad Celtis (1501/02) Archived 2013-03-19 at the Wayback Machine in: Primary Sources on Copyright (1450–1900), eds L. Bently & M. Kretschmer, www.copyrighthistory.org

- ^ a b Eckhard Höffner (8 December 2010). "Copyright and Structure of Author's Earnings, from his book:Geschichte und Wesen des Urheberrechts (History and Nature of Copyright)". Slideshare. Retrieved April 11, 2015.

- ^ a b de Sola Pool, Ithiel (1983). Technologies of freedom. Harvard University Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-674-87233-2.

- ^ Sanders, Karen (2003). Ethics & Journalism. Sage. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-7619-6967-9.

- ^ Ronan, Deazley (2006). Rethinking copyright: history, theory, language. Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-84542-282-0.

- ^ Ronan, Deazley (2006). Rethinking copyright: history, theory, language. Edward Elgar Publishing. pp. 13–14. ISBN 978-1-84542-282-0.

- ^ a b Jonathan, Rosenoer (1997). Cyberlaw: the law of the internet. Springer. pp. 34. ISBN 978-0-387-94832-4.

- ^ Ronan, Deazley (2006). Rethinking copyright: history, theory, language. Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-84542-282-0.

- ^ Van Horn Melton, James (2001). The rise of the public in Enlightenment Europe. Cambridge University Press. p. 139. ISBN 978-0-521-46969-2.

- ^ Keen, Paul (2004). Revolutions in Romantic literature: an anthology of print culture 1780–1832. Broadview Press. p. 80. ISBN 978-1-55111-352-4.

- ^ Ronan, Deazley (2006). Rethinking copyright: history, theory, language. Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-84542-282-0.

- ^ Rimmer, Matthew (2007). Digital copyright and the consumer revolution: hands off my iPod. Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-84542-948-5.

- ^ Marshall, Lee (2006). Bootlegging: romanticism and copyright in the music industry. Sage. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-7619-4490-4.

- ^ Van Horn Melton, James (2001). The rise of the public in Enlightenment Europe. Cambridge University Press. pp. 140–141. ISBN 978-0-521-46969-2.

- ^ Ronan, Deazley (2006). Rethinking copyright: history, theory, language. Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-84542-282-0.

- ^ Jonathan, Rosenoer (1997). Cyberlaw: the law of the internet. Springer. pp. 34–35. ISBN 978-0-387-94832-4.

- ^ Atkinson, Benedict. & Fitzgerald, Brian. (eds.) (2017). Copyright Law: Volume II: Application to Creative Industries in the 20th Century. Routledge. p181.

- ^ Dibble, Jeremy. (2002). Charles Villiers Stanford: Man and Musician Oxford University press. pp340-341. ISBN 9780198163831

- ^ Sanjek, Russell. (1988). American Popular Music and Its Business: The First Four Hundred Years. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195043105

- ^ Johns, Adrian. (2009). Piracy: The Intellectual Property Wars from Gutenberg to Gates. University of Chicago Press. p354. ISBN 9780226401195

- ^ Johns, Adrian. (2009). Piracy: The Intellectual Property Wars from Gutenberg to Gates. University of Chicago Press. pp349-352. ISBN 9780226401195

- ^ a b c d Yu, Peter K (2007). Intellectual Property and Information Wealth: Copyright and related rights. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 141–142. ISBN 978-0-275-98883-8.

- ^ Peter K, Yu (2007). Intellectual Property and Information Wealth: Copyright and related rights. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 142. ISBN 978-0-275-98883-8.

- ^ a b c Peter K, Yu (2007). Intellectual Property and Information Wealth: Copyright and related rights. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-275-98883-8.

- ^ a b c d MacQueen, Hector L; Charlotte Waelde; Graeme T Laurie (2007). Contemporary Intellectual Property: Law and Policy. Oxford University Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-19-926339-4.

- ^ Richard Stallman. "Reevaluating Copyright: The Public Must Prevail".

- ^ Samudrala, Ram (1994). "The Free Music Philosophy". Retrieved 2011-09-13.

- ^ Samudrala, Ram (1994). "A Primer on the Ethics of Intellectual Property". Retrieved 2011-09-13.

- ^ See Jessica Litman, Digital Copyright (2000), for a detailed discussion of the legislative history behind the passage of the 1998 Digital Millennium Copyright Act, one of the first statutes prohibiting circumvention.

Further reading

[edit]- Eaton S. Drone, A Treatise on the Law of Property in Intellectual Productions, Little, Brown, & Co. (1879).

- Dietrich A. Loeber, '"Socialist" Features of Soviet Copyright Law', Columbia Journal of Transnational Law, vol. 23, pp 297–313, 1984.

- Joseph Lowenstein, The Author's Due : Printing and the Prehistory of Copyright, University of Chicago Press, 2002

- Christopher May, "The Venetian Moment: New Technologies, Legal Innovation and the Institutional Origins of Intellectual Property", Prometheus, 20(2), 2002.

- Millar v. Taylor, 4 Burr. 2303, 98 Eng. Rep. 201 (K.B. 1769).

- Lyman Ray Patterson, Copyright in Historical Perspective, Vanderbilt University Press, 1968.

- Eric Anderson, Pimps and Ferrets: Copyright and Culture in the United States, 1831–1891, 2010. https://archive.org/details/PimpsAndFerretsCopyrightAndCultureInTheUnitedStates1831-1891

- Brendan Scott, "Copyright in a Frictionless World", First Monday, volume 6, number 9 (September 2001), http://firstmonday.org/issues/issue6_9/scott/index.html Archived 2012-02-07 at the Wayback Machine.

- Charles Forbes René de Montalembert, The Monks of the West from St Benedict to St Bernard, William Blackwood and Sons, London, 1867, Vol III.

- Augustine Birrell, Seven Lectures on the Law and History of Copyright in Books, Rothman Reprints Inc., 1899 (1971 reprint).

- Drahos, P. with Braithwaite, J., Information Feudalism, The New Press, New York, 2003. ISBN 1-56584-804-7(hc.)

- Paul Edward Geller, International Copyright Law and Practice, Matthew Bender. (2000).

- New International Encyclopedia

- Computer Associates International, Inc. v. Altai, Inc., 982 F.2d 693 (2d Cir. 1992)

- Armstrong, Elizabeth. Before Copyright: the French book-privilege system 1498-1526. Cambridge University Press (Cambridge: 1990)

- Siegrist, Hannes, The History and Current Problems of Intellectual Property (1600–2000), in: Axel Zerdick ... (eds.), E-merging Media. Communication and the Media Economy of the Future, Heidelberg 2004, p. 311–329.

- Gantz, John and Rochester, Jack B. (2005), Pirates of the Digital Millennium, Upper Saddle River: Financial Times Prentice Hall; ISBN 0-13-146315-2

- Löhr, Isabella, Intellectual cooperation in transnational networks: the league of nations and the globalization of intellectual property rights, in: Mathias Albert ... (eds.), Transnational political spaces. agents - structures - encounters, Frankfurt/Main 2009, p. 58–88.

- Ronan Deazley, Martin Kretschmer and Lionel Bently (eds) Privilege and Property: Essays on the History of Copyright. Open Book Publishers (Cambridge: 2010). ISBN 978-1-906924-18-8

- Selle, Hendrik; "Open Content? Ancient Thinking on Copyright", Revue internationale de droit de l’Antiquité 55 (2008) 469–84.

External links

[edit]- Primary Sources on Copyright (1450–1900) (British, French, German, Italian, US documents)

- International Copyright and Neighbouring Rights: The Berne Convention and Beyond Companion website with historical documents related to international copyright