Venice

Venice

| |

|---|---|

| Comune di Venezia | |

|

| |

| Coordinates: 45°26′15″N 12°20′9″E / 45.43750°N 12.33583°E | |

| Country | Italy |

| Region | Veneto |

| Metropolitan city | Venice (VE) |

| Frazioni | Chirignago, Favaro Veneto, Mestre, Marghera, Murano, Burano, Giudecca, Lido, Zelarino |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Luigi Brugnaro (CI) |

| Area | |

• Total | 414.57 km2 (160.07 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 1 m (3 ft) |

| Population (2020)[2] | |

• Total | 258,685 |

| • Density | 620/km2 (1,600/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Veneziano Venetian (English) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 30100 |

| Dialing code | 041 |

| ISTAT code | 027042 |

| Patron saint | St. Mark the Evangelist |

| Saint day | 25 April |

| Website | Official website |

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

Venice in autumn, with the Rialto Bridge in the background | |

| Criteria | Cultural: I, II, III, IV, V, VI |

| Reference | 394 |

| Inscription | 1987 (11th Session) |

Venice (/ˈvɛnɪs/ VEN-iss; Italian: Venezia [veˈnɛttsja] ⓘ; Venetian: Venesia [veˈnɛsja], formerly Venexia [veˈnɛzja]) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto region. It is built on a group of 127 islands that are separated by expanses of open water and by canals; portions of the city are linked by 472 bridges.[3] The islands are in the shallow Venetian Lagoon, an enclosed bay lying between the mouths of the Po and the Piave rivers (more exactly between the Brenta and the Sile). In 2020, around 258,685 people resided in greater Venice or the Comune di Venezia, of whom around 51,000 live in the historical island city of Venice (centro storico) and the rest on the mainland (terraferma). Together with the cities of Padua and Treviso, Venice is included in the Padua-Treviso-Venice Metropolitan Area (PATREVE), which is considered a statistical metropolitan area, with a total population of 2.6 million.[4]

The name is derived from the ancient Veneti people who inhabited the region by the 10th century BC.[5][6] The city was historically the capital of the Republic of Venice for almost a millennium, from 810 to 1797. It was a major financial and maritime power during the Middle Ages and Renaissance, and a staging area for the Crusades and the Battle of Lepanto, as well as an important centre of commerce—especially silk, grain, and spice, and of art from the 13th century to the end of the 17th. The city-state of Venice is considered to have been the first real international financial centre, emerging in the 9th century and reaching its greatest prominence in the 14th century.[7] This made Venice a wealthy city throughout most of its history.[8] For centuries Venice possessed numerous territories along the Adriatic Sea and within the Italian peninsula, leaving a significant impact on the architecture and culture that can still be seen today.[9][10] The Venetian Arsenal is considered by several historians to be the first factory in history and was the base of Venice's naval power.[11] The sovereignty of Venice came to an end in 1797, at the hands of Napoleon. Subsequently, in 1866, the city became part of the Kingdom of Italy.[12]

Venice has been known as "La Dominante", "La Serenissima", "Queen of the Adriatic", "City of Water", "City of Masks", "City of Bridges", "The Floating City", and "City of Canals". The lagoon and the city within the lagoon were inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1987, covering an area of 70,176.4 hectares (173,410 acres).[13] Venice is known for several important artistic movements – especially during the Italian Renaissance – and has played an important role in the history of instrumental and operatic music; it is the birthplace of Baroque music composers Tomaso Albinoni and Antonio Vivaldi.[14]

In the 21st century, Venice remains a very popular tourist destination, a major cultural centre, and has often been ranked one of the most beautiful cities in the world.[15][16] It has been described by The Times as one of Europe's most romantic cities[17] and by The New York Times as "undoubtedly the most beautiful city built by man".[18] However, the city faces challenges including an excessive number of tourists, pollution, tide peaks and cruise ships sailing too close to buildings.[19][20][21] In light of the fact that Venice and its lagoon are under constant threat, Venice's UNESCO listing has been under constant examination.[22]

History

[edit]Origins

[edit]| 421–476 | Western Roman Empire |

|---|---|

| 476–493 | Kingdom of Odoacer |

| 493–553 | Ostrogothic Kingdom |

| 553–584 | Eastern Roman Empire |

| 584–697 | Byzantine Empire (Exarchate of Ravenna) |

| 697–1797 |

|

| 1797–1805 |

|

| 1805–1814 |

|

| 1815–1848 |

|

| 1848–1849 |

|

| 1849–1866 |

|

| 1866–1943 |

|

| 1943–1945 |

|

| 1946–present |

|

Although no surviving historical records deal directly with the founding or building of Venice,[23] tradition and the available evidence have led several historians to agree that the original population of Venice consisted of refugees – from nearby Roman cities such as Patavium (Padua), Aquileia, Tarvisium (Treviso), Altinum, and Concordia (modern Portogruaro), as well as from the undefended countryside – who were fleeing successive waves of Germanic and Hun invasions.[24] This is further supported by the documentation on the so-called "apostolic families", the twelve founding families of Venice who elected the first doge, who in most cases trace their lineage back to Roman families.[25][26] Some late Roman sources reveal the existence of fishermen, on the islands in the original marshy lagoons, who were referred to as incolae lacunae ("lagoon dwellers"). The traditional founding is identified with the dedication of the first church, that of San Giacomo on the islet of Rialto (Rivoalto, "High Shore")—said to have taken place at the stroke of noon on 25 March 421 (the Feast of the Annunciation).[27][28][29]

Beginning as early as AD 166–168, the Quadi and Marcomanni destroyed the main Roman town in the area, present-day Oderzo. This part of Roman Italy was again overrun in the early 5th century by the Visigoths and, some 50 years later, by the Huns led by Attila. The last and most enduring immigration into the north of the Italian peninsula, that of the Lombards in 568, left the Eastern Roman Empire only a small strip of coastline in the current Veneto, including Venice. The Roman/Byzantine territory was organized as the Exarchate of Ravenna, administered from that ancient port and overseen by a viceroy (the Exarch) appointed by the Emperor in Constantinople. Ravenna and Venice were connected by just sea routes, and with the Venetians' isolation came increasing autonomy. New ports were built, including those at Malamocco and Torcello in the Venetian lagoon. The tribuni maiores formed the earliest central standing governing committee of the islands in the lagoon, dating from c. 568.[note 1]

The traditional first doge of Venice, Paolo Lucio Anafesto (Anafestus Paulicius), was elected in 697, as written in the oldest chronicle by John, deacon of Venice c. 1008. Some modern historians claim Paolo Lucio Anafesto was actually the Exarch Paul, and Paul's successor, Marcello Tegalliano, was Paul's magister militum (or "general"), literally "master of soldiers". In 726 the soldiers and citizens of the exarchate rose in a rebellion over the iconoclastic controversy, at the urging of Pope Gregory II. The exarch, held responsible for the acts of his master, Byzantine Emperor Leo III, was murdered, and many officials were put to flight in the chaos. At about this time, the people of the lagoon elected their own independent leader for the first time, although the relationship of this to the uprisings is not clear. Ursus was the first of 117 "doges" (doge is the Venetian dialectal equivalent of the Latin dux ("leader"); the corresponding word in English is duke, in standard Italian duca (see also "duce".) Whatever his original views, Ursus supported Emperor Leo III's successful military expedition to recover Ravenna, sending both men and ships. In recognition of this, Venice was "granted numerous privileges and concessions" and Ursus, who had personally taken the field, was confirmed by Leo as dux[30] and given the added title of hypatus (from the Greek for "consul").[31]

In 751, the Lombard King Aistulf conquered most of the Exarchate of Ravenna, leaving Venice a lonely and increasingly autonomous Byzantine outpost. During this period, the seat of the local Byzantine governor (the "duke/dux", later "doge"), was at Malamocco. Settlement on the islands in the lagoon probably increased with the Lombard conquest of other Byzantine territories, as refugees sought asylum in the area. In 775/6, the episcopal seat of Olivolo (San Pietro di Castello) was created. During the reign of duke Agnello Particiaco (811–827) the ducal seat moved from Malamocco to the more protected Rialto, within present-day Venice. The monastery of St Zachary and the first ducal palace and basilica of St. Mark, as well as a walled defense (civitatis murus) between Olivolo and Rialto, were subsequently built here.

Charlemagne sought to subdue the city to his rule. He ordered the pope to expel the Venetians from the Pentapolis along the Adriatic coast;[32] Charlemagne's own son Pepin of Italy, king of the Lombards, under the authority of his father, embarked on a siege of Venice itself. This, however, proved a costly failure. The siege lasted six months, with Pepin's army ravaged by the diseases of the local swamps and eventually forced to withdraw in 810. A few months later, Pepin himself died, apparently as a result of a disease contracted there. In the aftermath, an agreement between Charlemagne and the Byzantine Emperor Nicephorus in 814 recognized Venice as Byzantine territory, and granted the city trading rights along the Adriatic coast.

In 828 the new city's prestige increased with the acquisition, from Alexandria, of relics claimed to be of St Mark the Evangelist; these were placed in the new basilica. Winged lions – visible throughout Venice – are the emblem of St Mark. The patriarchal seat was also moved to Rialto. As the community continued to develop, and as Byzantine power waned, its own autonomy grew, leading to eventual independence.[33]

Expansion

[edit]

From the 9th to the 12th centuries, Venice developed into a powerful maritime empire (an Italian thalassocracy known also as repubblica marinara). In addition to Venice there were seven others: the most important ones were Genoa, Pisa, and Amalfi; and the lesser known were Ragusa, Ancona, Gaeta and Noli. Its own strategic position at the head of the Adriatic made Venetian naval and commercial power almost invulnerable.[34] With the elimination of pirates along the Dalmatian coast, the city became a flourishing trade centre between Western Europe and the rest of the world, especially with the Byzantine Empire and Asia, where its navy protected sea routes against piracy.[35]

The Republic of Venice seized a number of places on the eastern shores of the Adriatic before 1200, mostly for commercial reasons, because pirates based there were a menace to trade. The doge already possessed the titles of Duke of Dalmatia and Duke of Istria. Later mainland possessions, which extended across Lake Garda as far west as the Adda River, were known as the Terraferma; they were acquired partly as a buffer against belligerent neighbours, partly to guarantee Alpine trade routes, and partly to ensure the supply of mainland wheat (on which the city depended). In building its maritime commercial empire, Venice dominated the trade in salt,[36] acquired control of most of the islands in the Aegean, including Crete, and Cyprus in the Mediterranean, and became a major power-broker in the Near East. By the standards of the time, Venice's stewardship of its mainland territories was relatively enlightened and the citizens of such towns as Bergamo, Brescia, and Verona rallied to the defence of Venetian sovereignty when it was threatened by invaders.

Venice remained closely associated with Constantinople, being twice granted trading privileges in the Eastern Roman Empire, through the so-called golden bulls or "chrysobulls", in return for aiding the Eastern Empire to resist Norman and Turkish incursions. In the first chrysobull, Venice acknowledged its homage to the empire; but not in the second, reflecting the decline of Byzantium and the rise of Venice's power.[37]

Venice became an imperial power following the Fourth Crusade, which, having veered off course, culminated in 1204 by capturing and sacking Constantinople and establishing the Latin Empire. As a result of this conquest, considerable Byzantine plunder was brought back to Venice. This plunder included the gilt bronze horses from the Hippodrome of Constantinople, which were originally placed above the entrance to the cathedral of Venice, St Mark's Basilica (The originals have been replaced with replicas, and are now stored within the basilica.) After the fall of Constantinople, the former Eastern Roman Empire was partitioned among the Latin crusaders and the Venetians. Venice subsequently carved out a sphere of influence in the Mediterranean known as the Duchy of the Archipelago, and captured Crete.[38]

The seizure of Constantinople proved as decisive a factor in ending the Byzantine Empire as the loss of the Anatolian themes, after Manzikert. Although the Byzantines recovered control of the ravaged city a half-century later, the Byzantine Empire was terminally weakened, and existed as a ghost of its old self, until Sultan Mehmet The Conqueror took the city in 1453.

Situated on the Adriatic Sea, Venice had always traded extensively with the Byzantine Empire and the Middle East. By the late 13th century, Venice was the most prosperous city in all of Europe. At the peak of its power and wealth, it had 36,000 sailors operating 3,300 ships, dominating Mediterranean commerce. Venice's leading families vied with each other to build the grandest palaces and to support the work of the greatest and most talented artists. The city was governed by the Great Council, which was made up of members of the noble families of Venice. The Great Council appointed all public officials, and elected a Senate of 200 to 300 individuals. Since this group was too large for efficient administration, a Council of Ten (also called the Ducal Council, or the Signoria), controlled much of the administration of the city. One member of the great council was elected "doge", or duke, to be the chief executive; he would usually hold the title until his death, although several Doges were forced, by pressure from their oligarchical peers, to resign and retire into monastic seclusion, when they were felt to have been discredited by political failure.

The Venetian governmental structure was similar in some ways to the republican system of ancient Rome, with an elected chief executive (the doge), a senator-like assembly of nobles, and the general citizenry with limited political power, who originally had the power to grant or withhold their approval of each newly elected doge. Church and various private property was tied to military service, although there was no knight tenure within the city itself. The Cavalieri di San Marco was the only order of chivalry ever instituted in Venice, and no citizen could accept or join a foreign order without the government's consent. Venice remained a republic throughout its independent period, and politics and the military were kept separate, except when on occasion the Doge personally headed the military. War was regarded as a continuation of commerce by other means. Therefore, the city's early employment of large numbers of mercenaries for service elsewhere, and later its reliance on foreign mercenaries when the ruling class was preoccupied with commerce.

Although the people of Venice generally remained orthodox Roman Catholics, the state of Venice was notable for its freedom from religious fanaticism, and executed nobody for religious heresy during the Counter-Reformation. This apparent lack of zeal contributed to Venice's frequent conflicts with the papacy. In this context, the writings of the Anglican divine William Bedell are particularly illuminating. Venice was threatened with the interdict on a number of occasions and twice suffered its imposition. The second, most noted, occasion was in 1606, by order of Pope Paul V.[39]

The newly invented German printing press spread rapidly throughout Europe in the 15th century, and Venice was quick to adopt it. By 1482, Venice was the printing capital of the world; the leading printer was Aldus Manutius, who invented paperback books that could be carried in a saddlebag.[40] His Aldine Editions included translations of nearly all the known Greek manuscripts of the era.[41]

Decline

[edit]Venice's long decline started in the 15th century. Venice confronted the Ottoman Empire in the Siege of Thessalonica (1422–1430) and sent ships to help defend Constantinople against the besieging Turks in 1453. After the Fall of Constantinople, Sultan Mehmed II declared the first of a series of Ottoman-Venetian wars that cost Venice much of its eastern Mediterranean possessions. Vasco da Gama's 1497–1499 voyage opened a sea route to India around the Cape of Good Hope and destroyed Venice's monopoly. Venice's oared vessels were at a disadvantage when it came to traversing oceans, therefore Venice was left behind in the race for colonies.[42]

The Black Death devastated Venice in 1348 and struck again between 1575 and 1577.[43] In three years, the plague killed some 50,000 people.[44] In 1630, the Italian plague of 1629–31 killed a third of Venice's 150,000 citizens.[45]

Venice began to lose the position as a centre of international trade during the later part of the Renaissance as Portugal became Europe's principal intermediary in the trade with the East, striking at the very foundation of Venice's great wealth. France and Spain fought for hegemony over Italy in the Italian Wars, marginalising its political influence. However, Venice remained a major exporter of agricultural products and until the mid-18th century, a significant manufacturing centre.[42]

Modern age

[edit]The Republic of Venice lost its independence when Napoleon Bonaparte conquered Venice on 12 May 1797 during the War of the First Coalition. Napoleon was seen as something of a liberator by the city's Jewish population. He removed the gates of the Ghetto and ended the restrictions on when and where Jews could live and travel in the city.

Venice became Austrian territory when Napoleon signed the Treaty of Campo Formio on 12 October 1797. The Austrians took control of the city on 18 January 1798. Venice was taken from Austria by the Treaty of Pressburg in 1805 and became part of Napoleon's Kingdom of Italy. It was returned to Austria following Napoleon's defeat in 1814, when it became part of the Austrian-held Kingdom of Lombardy–Venetia. In 1848 a revolt briefly re-established the Venetian republic under Daniele Manin, but this was crushed in 1849. In 1866, after the Third Italian War of Independence, Venice, along with the rest of the Veneto, became part of the newly created Kingdom of Italy.

From the middle of the 18th century, Trieste and papal Ancona, both of which became free ports, competed with Venice more and more economically. Habsburg Trieste in particular boomed and increasingly served trade via the Suez Canal, which opened in 1869, between Asia and Central Europe, while Venice very quickly lost its competitive edge and commercial strength.[46]

During World War II, the historic city was largely free from attack, the only aggressive effort of note being Operation Bowler, a successful Royal Air Force precision strike on the German naval operations in the city in March 1945. The targets were destroyed with virtually no architectural damage inflicted on the city itself.[47] However, the industrial areas in Mestre and Marghera and the railway lines to Padua, Trieste, and Trento were repeatedly bombed.[48] On 29 April 1945, a force of British and New Zealand troops of the British Eighth Army, under Lieutenant General Freyberg, liberated Venice, which had been a hotbed of anti-Mussolini Italian partisan activity.[49][50]

Venice was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1987, inscribing it as "Venice and its Lagoon".

Geography

[edit]

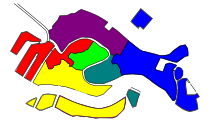

Venice is located in northeastern Italy, in the Veneto region. The city is situated on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by 438 bridges. The historic center of Venice is divided into six districts, or sestieri, which are named Cannaregio, Castello, Dorsoduro, San Marco, San Polo, and Santa Croce.

Venice sits atop alluvial silt washed into the sea by the rivers flowing eastward from the Alps across the Veneto plain, with the silt being stretched into long banks, or lidi, by the action of the current flowing around the head of the Adriatic Sea from east to west.[51]

Subsidence

[edit]Subsidence, the gradual lowering of the surface of Venice, has contributed – along with other factors – to the seasonal Acqua alta ("high water") when the city's lowest lying surfaces may be covered at high tide.

Building foundations

[edit]Those fleeing barbarian invasions who found refuge on the sandy islands of Torcello, Iesolo, and Malamocco, in this coastal lagoon, learned to build by driving closely spaced piles consisting of the trunks of alder trees, a wood noted for its water resistance, into the mud and sand,[52][53] until they reached a much harder layer of compressed clay. Building foundations rested on plates of Istrian limestone placed on top of the piles.[54]

Flooding

[edit]This section needs to be updated. The reason given is: MOSE information does not cover anything after 2020, such as the 2023 completion date moved to 2025. (February 2024) |

Between autumn and early spring, the city is often threatened by flood tides pushing in from the Adriatic. Six hundred years ago, Venetians protected themselves from land-based attacks by diverting all the major rivers flowing into the lagoon and thus preventing sediment from filling the area around the city.[55] This created an ever-deeper lagoon environment. Additionally, the lowest part of Venice, St Mark's Basilica, is only 64 centimetres (25 in) above sea level, and one of the most flood-prone parts of the city.[56]

In 1604, to defray the cost of flood relief, Venice introduced what could be considered the first example of a stamp tax.[57] When the revenue fell short of expectations in 1608, Venice introduced paper, with the superscription "AQ" and imprinted instructions, which was to be used for "letters to officials". At first, this was to be a temporary tax, but it remained in effect until the fall of the Republic in 1797. Shortly after the introduction of the tax, Spain produced similar paper for general taxation purposes, and the practice spread to other countries.

During the 20th century, when many artesian wells were sunk into the periphery of the lagoon to draw water for local industry, Venice began to subside. It was realized that extraction of water from the aquifer was the cause. The sinking has slowed markedly since artesian wells were banned in the 1960s. However, the city is still threatened by more frequent low-level floods – the Acqua alta, that rise to a height of several centimetres over its quays – regularly following certain tides. In many old houses, staircases once used to unload goods are now flooded, rendering the former ground floor uninhabitable.[citation needed]

Studies indicate that the city continues sinking at a relatively slow rate of 1–2 mm per year;[58][59] therefore, the state of alert has not been revoked.

In May 2003, Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi inaugurated the MOSE Project (Italian: Modulo Sperimentale Elettromeccanico), an experimental model for evaluating the performance of hollow floatable gates, expected to be completed in late 2023;[60] the idea is to fix a series of 78 hollow pontoons to the sea bed across the three entrances to the lagoon. When tides are predicted to rise above 110 centimetres (43 in), the pontoons will be filled with air, causing them to float on lagoon side while hinged at sea floor on seaside, thus blocking the incoming water from the Adriatic Sea.[61] This engineering work was due to be completed by 2018.[62] A Reuters report stated that the MOSE Project attributed the delay to "corruption scandals".[63] The project is not guaranteed to be successful and the cost has been very high, with as much as approximately €2 billion of the cost lost to corruption.[19]

According to a spokesman for the National Trust of Italy (Fondo Ambiente Italiano):[64]

Mose is a pharaonic project that should have cost €800m [£675m] but will cost at least €7bn [£6bn]. If the barriers are closed at only 90 cm of high water, most of St Mark's will be flooded anyway; but if closed at very high levels only, then people will wonder at the logic of spending such sums on something that didn't solve the problem. And pressure will come from the cruise ships to keep the gates open.

On 13 November 2019, Venice was flooded when waters peaked at 1.87 m (6 ft), the highest tide since 1966 (1.94 m).[65] More than 80% of the city was covered by water, which damaged cultural heritage sites, including more than 50 churches, leading to tourists cancelling their visits.[66][67] The planned flood barrier would have prevented this incident according to various sources, including Marco Piana, the head of conservation at St Mark's Basilica.[68] The mayor promised that work on the flood barrier would continue,[69][68] and the Prime Minister announced that the government would be accelerating the project.[66]

The city's mayor, Luigi Brugnaro, blamed the floods on climate change. The chambers of the Regional Council of Veneto began to be flooded around 10 pm, two minutes after the council rejected a plan to combat global warming.[70] One of the effects of climate change is sea level rise which causes an increase in frequency and magnitude of floodings in the city.[71] A Washington Post report provided a more thorough analysis:[72]

"The sea level has been rising even more rapidly in Venice than in other parts of the world. At the same time, the city is sinking, the result of tectonic plates shifting below the Italian coast. Those factors together, along with the more frequent extreme weather events associated with climate change, contribute to floods."

Henk Ovink, an expert on flooding, told CNN that, while environmental factors are part of the problem, "historic floods in Venice are not only a result of the climate crisis but poor infrastructure and mismanagement".[73]

The government of Italy committed to providing 20 million euros in funding to help the city repair the most urgent aspects although Brugnaro's estimate of the total damage was "hundreds of millions"[74] to at least 1 billion euros.[75]

On 3 October 2020, the MOSE was activated for the first time in response to a predicted high tide event, preventing some of the low-lying parts of the city (in particular the Piazza San Marco) from being flooded.[76]

Climate

[edit]According to the Köppen climate classification, Venice has a mid-latitude, four season humid subtropical climate (Cfa), with cool, damp winters and warm, humid summers. The 24-hour average temperature in January is 3.3 °C (37.9 °F), and for July this figure is 23.0 °C (73.4 °F). Precipitation is spread relatively evenly throughout the year, and averages 748 millimetres (29.4 in); snow isn't a rarity between late November and early March. During the most severe winters, the canals and parts of the lagoon can freeze, but with the warming trend of the past 30–40 years, the occurrence has become rarer.[77]

| Climate data for Venice, elevation: 2 m or 6 ft 7 in, (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1961–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 15.7 (60.3) |

22.0 (71.6) |

25.3 (77.5) |

27.2 (81.0) |

31.5 (88.7) |

35.2 (95.4) |

36.6 (97.9) |

36.5 (97.7) |

32.4 (90.3) |

27.3 (81.1) |

23.0 (73.4) |

16.7 (62.1) |

36.6 (97.9) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 7.5 (45.5) |

9.2 (48.6) |

13.2 (55.8) |

17.4 (63.3) |

22.0 (71.6) |

26.0 (78.8) |

28.5 (83.3) |

28.4 (83.1) |

23.8 (74.8) |

18.5 (65.3) |

12.9 (55.2) |

8.3 (46.9) |

18.0 (64.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 3.8 (38.8) |

5.0 (41.0) |

8.9 (48.0) |

13.0 (55.4) |

17.7 (63.9) |

21.7 (71.1) |

23.8 (74.8) |

23.7 (74.7) |

19.3 (66.7) |

14.5 (58.1) |

9.3 (48.7) |

4.7 (40.5) |

13.8 (56.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 0.1 (32.2) |

0.8 (33.4) |

4.5 (40.1) |

8.7 (47.7) |

13.5 (56.3) |

17.4 (63.3) |

19.2 (66.6) |

18.9 (66.0) |

14.8 (58.6) |

10.5 (50.9) |

5.7 (42.3) |

1.0 (33.8) |

9.6 (49.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −13.5 (7.7) |

−12.6 (9.3) |

−7.4 (18.7) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

2.0 (35.6) |

7.0 (44.6) |

10.2 (50.4) |

10.0 (50.0) |

5.0 (41.0) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

−8.8 (16.2) |

−12.5 (9.5) |

−13.5 (7.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 40.2 (1.58) |

56.5 (2.22) |

60.5 (2.38) |

70.5 (2.78) |

80.2 (3.16) |

64.2 (2.53) |

57.9 (2.28) |

65.8 (2.59) |

73.3 (2.89) |

72.0 (2.83) |

71.5 (2.81) |

49.8 (1.96) |

762.4 (30.01) |

| Average precipitation days | 6.0 | 5.2 | 5.7 | 8.3 | 8.2 | 8.6 | 5.9 | 6.1 | 5.9 | 6.7 | 5.8 | 5.9 | 78.3 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 81 | 77 | 75 | 75 | 73 | 74 | 71 | 72 | 75 | 77 | 79 | 81 | 76 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 80.6 | 107.4 | 142.6 | 174.0 | 229.4 | 243.0 | 288.3 | 257.3 | 198.0 | 151.9 | 87.0 | 77.5 | 2,037 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 2.6 | 3.8 | 4.6 | 5.8 | 7.4 | 8.1 | 9.3 | 8.3 | 6.6 | 4.9 | 2.9 | 2.5 | 5.6 |

| Mean daily daylight hours | 9.2 | 10.4 | 12.0 | 13.6 | 14.9 | 15.6 | 15.3 | 14.1 | 12.5 | 10.9 | 9.5 | 8.8 | 12.2 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 29 | 38 | 38 | 41 | 49 | 51 | 62 | 59 | 51 | 45 | 29 | 28 | 43 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| Source 1: Istituto Superiore per la Protezione e la Ricerca Ambientale[78]NOAA[79] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: MeteoAM (sun and humidity 1961–1990),[80][81] Weather Atlas (daylight, UV)[82] Temperature estreme in Toscana (extremes)[83] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Venice (sea temperatures) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 10.0 (50.0) |

8.8 (47.8) |

9.9 (49.8) |

13.4 (56.1) |

18.6 (65.5) |

23.4 (74.1) |

25.4 (77.7) |

25.4 (77.7) |

23.6 (74.5) |

19.3 (66.7) |

16.0 (60.8) |

13.3 (55.9) |

17.3 (63.0) |

| Source: Weather Atlas[82] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1871 | 164,965 | — |

| 1881 | 165,802 | +0.5% |

| 1901 | 189,368 | +14.2% |

| 1911 | 208,463 | +10.1% |

| 1921 | 223,373 | +7.2% |

| 1931 | 250,327 | +12.1% |

| 1936 | 264,027 | +5.5% |

| 1951 | 310,034 | +17.4% |

| 1961 | 339,671 | +9.6% |

| 1971 | 354,475 | +4.4% |

| 1981 | 336,081 | −5.2% |

| 1991 | 298,532 | −11.2% |

| 2001 | 271,073 | −9.2% |

| 2011 | 261,362 | −3.6% |

| 2021 | 251,944 | −3.6% |

| Source: ISTAT | ||

The city was one of the largest in Europe in the High Middle Ages, with a population of 60,000 in AD 1000; 80,000 in 1200; and rising up to 110,000–180,000 in 1300. In the mid-1500s the city's population was 170,000, and by 1600 it approached 200,000.[84][85][86][87][88]

In 2021, there were 254,850 people residing in the Comune of Venice (the population figure includes 50,434 in the historic city of Venice (Centro storico), 177,621 in Terraferma (the mainland); and 26,795 on other islands in the lagoon).[89] 47.8% of the population in 2021 were male and 52.2% were female; minors (ages 18 and younger) were 14.7% of the population compared to elderly people (ages 65 and older) who numbered 27.9%. This compared with the Italian average of 16.7% and 23.5%, respectively. The average age of Venice residents was 48.6 compared to the Italian average of 45.9. In the five years between 2016 and 2021, the population of Venice declined by 2.7%, while Italy as a whole declined by 2.2%.[90] The population in the historic old city declined much faster: from about 120,000 in 1980 to about 60,000 in 2009,[91] and to 50,000 in 2021.[89] As of 2021[update], 84.2% of the population was Italian. The largest immigrant groups include: 7,814 (3.1%) Bangladeshis, 6,258 (2.5%) Romanians, 4,054 (1.6%) Moldovans, 4,014 (1.6%) Chinese, and 2,514 (1%) Ukrainians.[92]

Venice is predominantly Roman Catholic (85.0% of the resident population in the area of the Patriarchate of Venice in 2022[93]), but because of the long-standing relationship with Constantinople, there is also a noticeable Orthodox presence; and as a result of immigration, there is now a large Muslim community (about 25,000 or 9.5% of city population in 2018[94]) and some Hindu, and Buddhist inhabitants.

Since 1991, the Church of San Giorgio dei Greci in Venice has become the see of the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of Italy and Malta and Exarchate of Southern Europe, a Byzantine-rite diocese under the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople.[95]

There is also a historic Jewish community in Venice. The Venetian Ghetto was the area in which Jews were compelled to live under the Venetian Republic. The word ghetto (ghèto), originally Venetian, is now found in many languages. Shakespeare's play The Merchant of Venice, written in the late 16th century, features Shylock, a Venetian Jew. The first complete and uncensored printed edition of the Talmud was printed in Venice by Daniel Bomberg in 1523. During World War II, Jews were rounded up in Venice and deported to extermination camps. Since the end of the war, the Jewish population of Venice has declined from 1500 to about 500.[96] Only around 30 Jews live in the former ghetto, which houses the city's major Jewish institutions.[97] In modern times, Venice has an eruv,[98] used by the Jewish community.

Government

[edit]Local and regional government

[edit]The legislative body of the Comune is the City Council (Consiglio Comunale), which is composed of 36 councillors elected every five years with a proportional system, contextually to the mayoral elections. The executive body is the City Administration (Giunta Comunale), composed of 12 assessors nominated and presided over by a directly elected Mayor.

Venice was governed by centre-left parties from the early 1990s until the 2010s, when the Mayor started to be elected directly. Its region, Veneto, has long been a conservative stronghold, with the coalition between the regionalist Lega Nord and the centre-right Forza Italia winning absolute majorities of the electorate in many elections at local, national, and regional levels.

The current mayor of Venice is Luigi Brugnaro, a centre-right independent businessman who is currently serving his second term in office.

The municipality of Venice is also subdivided into six administrative boroughs (municipalità). Each borough is governed by a council (Consiglio) and a president, elected every five years. The urban organization is dictated by Article 114 of the Italian Constitution. The boroughs have the power to advise the Mayor with nonbinding opinions on a large spectrum of topics (environment, construction, public health, local markets) and exercise the functions delegated to them by the City Council; in addition, they are supplied with autonomous funding to finance local activities.

| Borough | Place | Population | President | Party | Term | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Venezia (Historic city)–Murano–Burano | Lagoon area | 69,136 | Marco Borghi | PD | 2020–2025 | |

| 2 | Lido–Pellestrina | Lagoon area | 21,664 | Emilio Guberti | Ind | 2020–2025 | |

| 3 | Favaro Veneto | Mainland (terraferma)[a] | 23,615 | Marco Bellato | Ind | 2020–2025 | |

| 4 | Mestre–Carpenedo | Mainland (terraferma) | 88,592 | Raffaele Pasqualetto | LN | 2020–2025 | |

| 5 | Chirignago–Zelarino | Mainland (terraferma) | 38,179 | Francesco Tagliapietra | Ind | 2020–2025 | |

| 6 | Marghera | Mainland (terraferma) | 28,466 | Teodoro Marolo | Ind | 2020–2025 | |

- Notes

- ^ Annexed with a Royal Decree to the municipality of Venice in 1926.

Sestieri

[edit]The historic city of Venice has historically been divided into six sestieri, and is made up of a total of 127 individual islands, most of which are separated from their neighbors by narrow channels only.[99]

| Sestiere | Abbr. | Area (ha) | Pop. (2011-10-09) | Density | No. of islands |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cannaregio | CN | 121.36 | 16.950 | 13.967 | 33 |

| Castello | CS | 173.97 | 14.813 | 8.514 | 26 |

| San Marco | SM | 54.48 | 4.145 | 7.552 | 16 |

| Dorsoduro | DD | 161.32 | 13.398 | 8.305 | 31 |

| San Polo | SP | 46.70 | 9.183 | 19.665 | 7 |

| Santa Croce | SC | 88.57 | 2.257 | 2.548 | 14 |

| Historic centre | — | 646.80[citation needed] | 60.746 | 9.392 | 127 |

Each sestiere is now a statistical and historical area without any degree of autonomy.[100]

The six fingers or phalanges of the ferro on the bow of a gondola represent the six sestieri.[100]

The sestieri are divided into parishes—initially 70 in 1033, but reduced under Napoleon, and now numbering just 38. These parishes predate the sestieri, which were created in about 1170. Each parish exhibited unique characteristics but also belonged to an integrated network. Each community chose its own patron saint, staged its own festivals, congregated around its own market centre, constructed its own bell towers, and developed its own customs.[101]

Other islands of the Venetian Lagoon do not form part of any of the sestieri, having historically enjoyed a considerable degree of autonomy.[102]

Each sestiere has its own house numbering system. Each house has a unique number in the district, from one to several thousand, generally numbered from one corner of the area to another, but not usually in a readily understandable manner.[102]

Economy

[edit]

Venice's economy has changed throughout history. Although there is little specific information about the earliest years, it is likely that an important source of the city's prosperity was the trade in slaves, captured in central Europe and sold to North Africa and the Levant. Venice's location at the head of the Adriatic, and directly south of the terminus of the Brenner Pass over the Alps, would have given it a distinct advantage as a middleman in this important trade. In the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, Venice was a major centre for commerce and trade, as it controlled a vast sea-empire, and became an extremely wealthy European city and a leader in political and economic affairs.[103] From the 11th century until the 15th century, pilgrimages to the Holy Land were offered in Venice. Other ports such as Genoa, Pisa, Marseille, Ancona, and Dubrovnik were hardly able to compete with the well organized transportation of pilgrims from Venice.[104][105]

Armenian merchants from Julfa were the leading traders in Venice, especially the Sceriman family in the 17th century. They were specialized in the gems and diamonds business.[106] The trade volume reached millions of tons, which was exceptional for 17th century.[107] This all changed by the 17th century, when Venice's trade empire was taken over by countries such as Portugal, and its importance as a naval power was reduced. In the 18th century, it became a major agricultural and industrial exporter. The 18th century's biggest industrial complex was the Venice Arsenal, and the Italian Army still uses it today (even though some space has been used for major theatrical and cultural productions, and as spaces for art).[108] Since World War II, many Venetians have moved to the neighboring cities of Mestre and Porto Marghera, seeking employment as well as affordable housing.[109]

Today, Venice's economy is mainly based on tourism, shipbuilding (mainly in Mestre and Porto Marghera), services, trade, and industrial exports.[103] Murano glass production in Murano and lace production in Burano are also highly important to the economy.[103]

The city is facing financial challenges. In late 2016, it had a major deficit in its budget and debts in excess of €400 million. "In effect, the place is bankrupt", according to a report by The Guardian.[20] Many locals are leaving the historic centre due to rapidly increasing rents. The declining native population affects the character of the city, as an October 2016 National Geographic article pointed out in its subtitle: "Residents are abandoning the city, which is in danger of becoming an overpriced theme park".[19] The city is also facing other challenges, including erosion, pollution, subsidence, an excessive number of tourists in peak periods, and problems caused by oversized cruise ships sailing close to the banks of the historical city.[19]

In June 2017, Italy was required to bail out two Venetian banks – the Banca Popolare di Vicenza and Veneto Banca – to prevent their bankruptcies.[110] Both banks would be wound down and their assets that have value taken over by another Italian bank, Intesa Sanpaolo, which would receive €5.2 billion as compensation. The Italian government would be responsible for losses from any uncollectible loans from the closed banks. The cost would be €5.2 billion, with further guarantees to cover bad loans totaling €12 billion.[111]

Tourism

[edit]

Venice is an important destination for tourists who want to see its celebrated art and architecture.[108] The city hosts up to 60,000 tourists per day (2017 estimate). Estimates of the annual number of tourists vary from 22 million to 30 million.[112][113][114] This "overtourism" creates overcrowding and environmental problems for Venice's ecosystem. By 2017, UNESCO was considering the addition of Venice to its "In-Danger" list, which includes historical ruins in war-torn countries. To reduce the number of visitors, who are causing irreversible changes in Venice, the agency supports limiting the number of cruise ships[115] as well as implementing a strategy for more sustainable tourism.[116]

Tourism has been a major part of the Venetian economy since the 18th century, when Venice – with its beautiful cityscape, uniqueness, and rich musical and artistic cultural heritage – was a stop on the Grand Tour. In the 19th century, Venice became a fashionable centre for the "rich and famous", who often stayed and dined at luxury establishments such as the Danieli Hotel and the Caffè Florian, and continued to be a fashionable city into the early 20th century.[108] In the 1980s, the Carnival of Venice was revived; and the city has become a major centre of international conferences and festivals, such as the prestigious Venice Biennale and the Venice Film Festival, which attract visitors from all over the world for their theatrical, cultural, cinematic, artistic, and musical productions.[108]

Today, there are numerous attractions in Venice, such as St Mark's Basilica, the Doge's Palace, the Grand Canal, and the Piazza San Marco. The Lido di Venezia is also a popular international luxury destination, attracting thousands of actors, critics, celebrities, and others in the cinematic industry. The city also relies heavily on the cruise business.[108] The Cruise Venice Committee has estimated that cruise ship passengers spend more than 150 million euros (US$193 million) annually in the city, according to a 2015 report.[117] Other reports, however, point out that such day-trippers spend relatively little in the few hours of their visits to the city.[20]

Venice is regarded by some as a tourist trap, and by others as a "living museum".[108]

Diverting cruise ships

[edit]

The need to protect the city's historic environment and fragile canals, in the face of a possible loss of jobs produced by cruise tourism, has seen the Italian Transport Ministry attempt to introduce a ban on large cruise ships visiting the city. A 2013 ban would have allowed only cruise ships smaller than 40,000-gross tons to enter the Giudecca Canal and St Mark's basin.[118] In January 2015, a regional court scrapped the ban, but some global cruise lines indicated that they would continue to respect it until a long-term solution for the protection of Venice is found.[119]

P&O Cruises removed Venice from its summer schedule; Holland America moved one of its ships from this area to Alaska; and Cunard reduced (in 2017 and further in 2018) the number of visits by its ships. As a result, the Venice Port Authority estimated an 11.4 per cent drop in cruise ships arriving in 2017 versus 2016, leading to a similar reduction in income for Venice.[120]

Having failed in its 2013 bid to ban oversized cruise ships from the Giudecca Canal, the Italian inter-ministerial Comitatone overseeing Venice's lagoon released an official directive in November 2017 to keep the largest cruise ships away from the Piazza San Marco and the entrance to the Grand Canal.[121][122][123] Ships over 55,000 tons will be required to follow a specific route through the Vittorio Emmanuele III Canal to reach Marghera, an industrial area of the mainland, where a passenger terminal would be built.[124]

In 2014, the United Nations warned the city that it may be placed on UNESCO's List of World Heritage in Danger sites unless cruise ships are banned from the canals near the historic centre.[125]

According to the officials, the plan to create an alternative route for ships would require extensive dredging of the canal and the building of a new port, which would take four years, in total, to complete. However, the activist group No Grandi Navi (No big Ships), argued that the effects of pollution caused by the ships would not be diminished by the re-routing plan.[126][127]

Some locals continued to aggressively lobby for new methods that would reduce the number of cruise ship passengers; their estimate indicated that there are up to 30,000 such sightseers per day at peak periods,[114] while others concentrate their effort on promoting a more responsible way of visiting the city.[128] An unofficial referendum to ban large cruise ships was held in June 2017. More than 18,000 people voted at 60 polling booths set up by activists, and 17,874 favored banning large ships from the lagoon. The population of Venice at the time was about 50,000.[129] The organizers of the referendum backed a plan to build a new cruise ship terminal at one of the three entrances to the Venetian Lagoon. Passengers would be transferred to the historic area in smaller boats.[130][131]

On 2 June 2019, the cruise ship MSC Opera rammed a tourist riverboat, the River Countess, which was docked on the Giudecca Canal, injuring five people, in addition to causing property damage. The incident immediately led to renewed demands to ban large cruise ships from the Giudecca Canal,[132] including a Twitter message to that effect posted by the environment minister. The city's mayor urged authorities to accelerate the steps required for cruise ships to begin using the alternate Vittorio Emanuele canal.[133] Italy's transport minister spoke of a "solution to protect both the lagoon and tourism ... after many years of inertia" but specifics were not reported.[134][135] As of June 2019[update], the 2017 plan to establish an alternative route for large ships, preventing them from coming near the historic area of the city, has not yet been approved.[127]

Nonetheless, the Italian government released an announcement on 7 August 2019 that it would begin rerouting cruise ships larger than 1000 tonnes away from the historic city's Giudecca Canal. For the last four months of 2019, all heavy vessels will dock at the Fusina and Lombardia terminals which are still on the lagoon but away from the central islands. By 2020, one-third of all cruise ships will be rerouted, according to Danilo Toninelli, the minister for Venice. Preparation work for the Vittorio Emanuele Canal needed to begin soon for a long-term solution, according to the Cruise Lines International Association.[136][137] In the long-term, space for ships would be provided at new terminals, perhaps at Chioggia or Lido San Nicolo. That plan was not imminent however, since public consultations had not yet begun. Over 1.5 million people per year arrive in Venice on cruise ships.[138] The Italian government decided to divert large cruise ships beginning August 2021.[139]

Other tourism mitigation efforts

[edit]

Having failed in its 2013 bid to ban oversized cruise ships from the Giudecca Canal, the city switched to a new strategy in mid-2017, banning the creation of any additional hotels. Currently, there are over 24,000 hotel rooms. The ban does not affect short-term rentals in the historic centre which are causing an increase in the cost of living for the native residents of Venice.[20] The city had already banned any additional fast food "take-away" outlets, to retain the historic character of the city, which was another reason for freezing the number of hotel rooms.[140] Fewer than half of the millions of annual visitors stay overnight, however.[112][113]

The city also considered a ban on wheeled suitcases, but settled for banning hard plastic wheels for transporting cargo from May 2015.[141]

In addition to accelerating erosion of the ancient city's foundations and creating some pollution in the lagoon,[19][142] cruise ships dropping an excessive number of day trippers can make St. Marks Square and other popular attractions too crowded to walk through during the peak season. Government officials see little value to the economy from the "eat and flee" tourists who stay for less than a day, which is typical of those from cruise ships.[129]

On 28 February 2019, the Venice City Council voted in favour of a new municipal regulation requiring day-trippers visiting the historic centre, and the islands in the lagoon, to pay a new access fee. The extra revenue from the fee would be used for cleaning, maintaining security, reducing the financial burden on residents of Venice, and to "allow Venetians to live with more decorum". The new tax would be between €3 and €10 per person, depending on the expected tourist flow into the old city. The fee could be waived for certain types of travelers: including students, children under the age of 6, voluntary workers, residents of the Veneto region, and participants in sporting events.[143] Overnight visitors, who already pay a "stay" tax and account for around 40% of Venice's yearly total of 28 million visitors,[144] would also be exempted. The access fee was expected to come into effect in September 2019; but it was postponed, firstly, until 1 January 2020, and then, again, due to the coronavirus pandemic.[145] The new charge of €5 started to be imposed on those tourists who are not staying overnight and came into force on 25 April 2024.[146] It is only charged on peak visitor days, and several classes of people are exempt, including Veneto residents, hotel guests (including mainland boroughs of Venice), local workers, and students.[147] Cell phone data showed more tourists came on fee-charged days in 2024, generating more money than expected, and leaving the city to decide whether to raise the fee for the next tourist season or try other approaches.[148]

A regulation taking effect on June 1, 2024, limits tour groups to 25 people and bans loudspeakers.[149][150]

Transport

[edit]In the historic centre

[edit]

Venice is built on an archipelago of 118 islands[13] in a shallow, 550 km2 (212 sq mi) lagoon,[151] connected by 400 bridges[152] over 177 canals. In the 19th century, a causeway to the mainland brought the railroad to Venice. The adjoining Ponte della Libertà road causeway and terminal parking facilities in Tronchetto island and Piazzale Roma were built during the 20th century. Beyond these rail and road terminals on the northern edge of the city, transportation within the city's historic centre remains, as it was in centuries past, entirely on water or on foot. Venice is Europe's largest urban car-free area and is unique in Europe in having remained a sizable functioning city in the 21st century entirely without motorcars or trucks.

The classic Venetian boat is the gondola, (plural: gondole) although it is now mostly used for tourists, or for weddings, funerals, or other ceremonies, or as traghetti[clarification needed] (sing.: traghetto) to cross the Grand Canal in lieu of a nearby bridge. The traghetti are operated by two oarsmen.[153]

There are approximately 400 licensed gondoliers in Venice, in their distinctive livery, and a similar number of boats, down from 10,000 two centuries ago.[when?][154][155] Many gondolas are lushly appointed with crushed velvet seats and Persian rugs. At the front of each gondola that works in the city, there is a large piece of metal called the fèro (iron). Its shape has evolved through the centuries, as documented in many well-known paintings. Its form, topped by a likeness of the Doge's hat, became gradually standardized, and was then fixed by local law. It consists of six bars pointing forward representing the sestieri of the city, and one that points backwards representing the Giudecca.[155][156] A lesser-known boat is the smaller, simpler, but similar, sandolo.

Waterways

[edit]Venice's small islands were enhanced during the Middle Ages by the dredging of soil to raise the marshy ground above the tides. The resulting canals encouraged the flourishing of a nautical culture which proved central to the economy of the city. Today those canals still provide the means for transport of goods and people within the city.

The maze of canals threading through the city requires more than 400 bridges to permit the flow of foot traffic. In 2011, the city opened the Ponte della Costituzione, the fourth bridge across the Grand Canal, which connects the Piazzale Roma bus-terminal area with the Venezia Santa Lucia railway station. The other bridges are the original Ponte di Rialto, the Ponte dell'Accademia, and the Ponte degli Scalzi.

Public transport

[edit]Azienda del Consorzio Trasporti Veneziano (ACTV) is a public company responsible for public transportation in Venice.

Lagoon area

[edit]

The main means of public transportation consists of motorised waterbuses (vaporetti) which ply regular routes along the Grand Canal and between the city's islands. Private motorised water taxis are also active. The only gondole still in common use by Venetians are the traghetti, foot passenger ferries crossing the Grand Canal at certain points where there are no convenient bridges. Other gondole are rented by tourists on an hourly basis.[155]

The Venice People Mover is an elevated shuttle train public transit system connecting Tronchetto island with its car parking facility with Piazzale Roma where visitors arrive in the city by bus, taxi, or automobile. The train makes a stop at the Marittima cruise terminal at the Port of Venice.[157]

Lido and Pellestrina islands

[edit]Lido and Pellestrina are two islands forming a barrier between the southern Venetian Lagoon and the Adriatic Sea. On those islands, road traffic, including bus service, is allowed. Vaporetti link them with other islands (Venice, Murano, Burano) and with the peninsula of Cavallino-Treporti.

Mainland

[edit]

The mainland of Venice is composed of 4 boroughs: Mestre-Carpenedo, Marghera, Chirignago-Zelarino, and Favaro Veneto. Mestre is the centre and the most populous urban area of the mainland. There are several bus routes and two Translohr tramway lines. Several bus routes and one of the tramway lines link the mainland with Piazzale Roma, the main bus station in Venice, via Ponte della Libertà, the road bridge connecting the mainland with the group of islands that comprise the historic centre of Venice.

The average amount of time people spend commuting with public transit in Venice, for example to and from work, on a weekday is 52 min. Only 12.2% of public transit riders ride for more than 2 hours every day. The average amount of time people wait at a stop or station for public transit is 10 min, while 17.6% of riders wait for over 20 minutes on average every day. The average distance people usually ride in a single trip with public transit is 7 kilometres (4.3 mi), while 12% travel for over 12 kilometres (7.5 mi) in a single direction.[158]

Rail

[edit]

Venice is served by regional and national trains, including trains to Florence (1h53), Milan (2h13), Turin (3h10), Rome (3h33), and Naples (4h50). In addition there are international day trains to Zurich, Innsbruck, Munich, and Vienna, plus overnight sleeper services, to Paris and Dijon on Thello trains, and to Munich and Vienna via Austrian Federal Railways.

- The Venezia Santa Lucia railway station is a few steps away from a vaporetti stop, Ferovia, in the historic city next to the Piazzale Roma. This station is the terminus of local trains and of the luxury Venice Simplon Orient Express from London via Paris and other cities.

- The Venezia Mestre railway station is on the mainland, on the border between the boroughs of Mestre and Marghera.

Both stations are managed by Grandi Stazioni; they are linked by the Ponte della Libertà (Liberty Bridge) between the mainland and the city centre.

Other stations in the municipality are Venezia Porto Marghera, Venezia Carpenedo, Venezia Mestre Ospedale, and Venezia Mestre Porta Ovest.

Ports

[edit]

The Port of Venice (Italian: Porto di Venezia) is the eighth-busiest commercial port in Italy and was a major hub for the cruise sector in the Mediterranean, as since August 2021 ships of more 25,000 tons are forbidden to pass the Giudecca Canal. It is one of the major Italian ports and is included in the list of the leading European ports which are located on the strategic nodes of trans-European networks. In 2002, the port handled 262,337 containers. In 2006, 30,936,931 tonnes passed through the port, of which 14,541,961 was commercial traffic, and saw 1,453,513 passengers.[159]

Aviation

[edit]The Marco Polo International Airport (Aeroporto di Venezia Marco Polo) is named in honor of Marco Polo. The airport is on the mainland and was rebuilt away from the coast. Public transport from the airport takes one to:

- Venice Piazzale Roma by ATVO (provincial company) buses[160] and by ACTV (city company) buses (route 5 aerobus);[161]

- Venice, Lido, and Murano by Allilaguna (private company) motor boats;

- Mestre, the mainland, where Venice Mestre railway station is convenient for connections to Milan, Padua, Trieste, Verona and the rest of Italy, and for ACTV (routes 15 and 45)[161] and ATVO buses and other transport;

- Regional destinations, such as Treviso and Padua, by ATVO and Busitalia Sita Nord buses.[162]

Venice-Treviso Airport, about 30 kilometres (19 mi) from Venice, is used mainly by low-cost airlines. There are public buses from this airport to Venice.[163] Venezia-Lido "Giovanni Nicelli",[164] a public airport suitable for smaller aircraft, is at the northeast end of Lido di Venezia. It has a 994-metre (3,261 ft) grass runway.

Sport

[edit]The most famous Venetian sport is probably Voga alla Veneta ("Venetian-style rowing"), also commonly called voga veneta. A technique invented in the Venetian Lagoon, Venetian rowing is unusual in that the rower(s), one or more, row standing, looking forward. Today, Voga alla Veneta is not only the way the gondoliers row tourists around Venice but also the way Venetians row for pleasure and sport. Many races called regata(e) happen throughout the year.[165] The culminating event of the rowing season is the day of the "Regata Storica", which occurs on the first Sunday of September each year.[166]

The main football club in the city is Venezia F.C., founded in 1907, which currently plays in the Serie A. Their ground, the Stadio Pier Luigi Penzo, situated in Sant'Elena, is the second-oldest continually used stadium in Italy.

The local basketball club is Reyer Venezia, founded in 1872 as the gymnastics club Società Sportiva Costantino Reyer, and in 1907 as the basketball club. Reyer currently plays in the Lega Basket Serie A. The men's team were the Italian champions in 1942, 1943, and 2017. Their arena is the Palasport Giuseppe Taliercio, situated in Mestre. Luigi Brugnaro is both the president of the club and the mayor of the city.

Education

[edit]

Venice is a major international centre for higher education. The city hosts the Ca' Foscari University of Venice, founded in 1868; the Università Iuav di Venezia, founded in 1926; the Venice International University, founded in 1995 and located on the island of San Servolo and the EIUC-European Inter-University Centre for Human Rights and Democratisation, located on the island of Lido di Venezia.[167]

Other Venetian institutions of higher education are: the Accademia di Belle Arti (Academy of Fine Arts), established in 1750, whose first chairman was Giovanni Battista Piazzetta, and the Benedetto Marcello Conservatory of Music, which was first established in 1876 as a high school and musical society, later (1915) became Liceo Musicale, and then, when its director was Gian Francesco Malipiero, the State Conservatory of Music (1940).[168]

Culture

[edit]Literature

[edit]

Venice has long been a source of inspiration for authors, playwrights, and poets, and at the forefront of the technological development of printing and publishing.

Two of the most noted Venetian writers were Marco Polo in the Middle Ages and, later, Giacomo Casanova. Polo (1254–1324) was a merchant who voyaged to the Orient. His series of books, co-written with Rustichello da Pisa and titled Il Milione provided important knowledge of the lands east of Europe, from the Middle East to China, Japan, and Russia. Giacomo Casanova (1725–1798) was a prolific writer and adventurer best remembered for his autobiography, Histoire De Ma Vie (Story of My Life), which links his colourful lifestyle to the city of Venice.

Venetian playwrights followed the old Italian theatre tradition of commedia dell'arte. Ruzante (1502–1542), Carlo Goldoni (1707–1793), and Carlo Gozzi (1720–1806) used the Venetian dialect extensively in their comedies.

Venice has also inspired writers from abroad. Shakespeare set Othello and The Merchant of Venice in the city, as did Thomas Mann his novel, Death in Venice (1912). The French writer Philippe Sollers spent most of his life in Venice and published A Dictionary For Lovers of Venice in 2004.

The city features prominently in Henry James's The Aspern Papers and The Wings of the Dove. It is also visited in Evelyn Waugh's Brideshead Revisited and Marcel Proust's In Search of Lost Time. Perhaps the best-known children's book set in Venice is The Thief Lord, written by the German author Cornelia Funke.

Venice is described in Goethe's Italian Journey, 1786–1788. He describes the architecture, including a church by Palladio and also attends the opera. He visits the shipbuilding yards at the Arsenal. He is fascinated by the street life of Venice, which he describes as a kind of performance.

The poet Ugo Foscolo (1778–1827), born in Zante, an island that at the time belonged to the Republic of Venice, was also a revolutionary who wanted to see a free republic established in Venice following its fall to Napoleon.

Venice also inspired the poetry of Ezra Pound, who wrote his first literary work in the city. Pound died in 1972, and his remains are buried in Venice's cemetery island of San Michele.

Venice is also linked to the technological aspects of writing. The city was the location of one of Italy's earliest printing presses called Aldine Press, established by Aldus Manutius in 1494.[169] From this beginning Venice developed as an important typographic centre. Around fifteen percent of all printing of the fifteenth century came from Venice,[170] and even as late as the 18th century was responsible for printing half of Italy's published books.[citation needed]

In literature and adapted works

[edit]The city is a particularly popular setting for essays, novels, and other works of fictional or non-fictional literature. Examples of these include:

- Aretino's works (1492–1556)

- Shakespeare's Merchant of Venice (c. 1596–1598) and Othello (1603).

- Ben Jonson's Volpone (1605–6).

- Casanova's autobiographical History of My Life c. 1789–1797.

- Voltaire's Candide (1759).

- Letitia Elizabeth Landon wrote poetry for two pictures of Venice; one for The Embarkation, drawn by Clarkson Stanfield for The Amulet, 1833, the other for Santa Salute, drawn by Charles Bentley for the Literary Souvenir, 1835.

- Ernest Hemingway's Across the River and into the Trees (1950).

- Italo Calvino's Invisible Cities (1972).

- Anne Rice's Cry to Heaven (1982).

- Donna Leon's Commissario Guido Brunetti crime fiction series and cookbook, and the German television series based on the novels (1992–2019).

- Philippe Sollers' Watteau in Venice (1994).

- Michael Dibdin's Dead Lagoon (1994), one in a series of novels featuring Venice-born policeman Aurelio Zen.

- Jacqueline Carey's Kushiel's Chosen (2002), an historical fantasy or alternate history of Venice – complete with masquerades, canals, and a doge – taking place in a city known as La Serenissima.

- John Berendt's The City of Falling Angels (2005)

- Gilbert and Sullivan's comic opera The Gondoliers (1889)

- Thomas Mann's novella, Death in Venice (1912), was the basis for Benjamin Britten's eponymous opera (1973).

Foreign words of Venetian origin

[edit]Some English words with a Venetian etymology include arsenal, ciao, ghetto, gondola, imbroglio, lagoon, lazaret, lido, Montenegro, and regatta.[171]

Printing

[edit]By the end of the 15th century, Venice had become the European capital of printing, having 417 printers by 1500, and being one of the first cities in Italy (after Subiaco and Rome) to have a printing press, after those established in Germany. The most important printing office was the Aldine Press of Aldus Manutius; which in 1497 issued the first printed work of Aristotle; in 1499 printed the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, considered the most beautiful book of the Renaissance; and established modern punctuation, page format, and italic type.

Painting

[edit]

Venice, especially during the Renaissance, and Baroque periods, was a major centre of art and developed a unique style known as the Venetian painting. In the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, Venice, along with Florence and Rome, became one of the most important centres of art in Europe, and numerous wealthy Venetians became patrons of the arts. Venice at the time was a rich and prosperous Maritime Republic, which controlled a vast sea and trade empire.[172]

In the 16th century, Venetian painting was developed through influences from the Paduan School and Antonello da Messina, who introduced the oil painting technique of the Van Eyck brothers. It is signified by a warm colour scale and a picturesque use of colour. Early masters were the Bellini and Vivarini families, followed by Giorgione and Titian, then Tintoretto and Veronese. In the early 16th century, there was rivalry in Venetian painting between the disegno and colorito techniques.[173]

Canvases (the common painting surface) originated in Venice during the early Renaissance. In the 18th century, Venetian painting had a revival with Tiepolo's decorative painting and Canaletto's and Guardi's panoramic views.

Venetian architecture

[edit]

Venice is built on unstable mud-banks, and had a very crowded city centre by the Middle Ages. On the other hand, the city was largely safe from riot, civil feuds, and invasion much earlier than most European cities. These factors, with the canals and the great wealth of the city, made for unique building styles.

Venice has a rich and diverse architectural style, the most prominent of which is the Gothic style. Venetian Gothic architecture is a term given to a Venetian building style combining the use of the Gothic lancet arch with the curved ogee arch, due to Byzantine and Ottoman influences. The style originated in 14th-century Venice, with a confluence of Byzantine style from Constantinople, Islamic influences from Spain and Venice's eastern trading partners, and early Gothic forms from mainland Italy.[citation needed] Chief examples of the style are the Doge's Palace and the Ca' d'Oro in the city. The city also has several Renaissance and Baroque buildings, including the Ca' Pesaro and the Ca' Rezzonico.

Venetian taste was conservative and Renaissance architecture only really became popular in buildings from about the 1470s. More than in the rest of Italy, it kept much of the typical form of the Gothic palazzi, which had evolved to suit Venetian conditions. In turn the transition to Baroque architecture was also fairly gentle. This gives the crowded buildings on the Grand Canal and elsewhere an essential harmony, even where buildings from very different periods sit together. For example, round-topped arches are far more common in Renaissance buildings than elsewhere.

Rococo style

[edit]It can be argued that Venice produced the best and most refined Rococo designs. At the time, the Venetian economy was in decline. It had lost most of its maritime power, was lagging behind its rivals in political importance, and its society had become decadent, with tourism increasingly the mainstay of the economy. But Venice remained a centre of fashion.[174] Venetian rococo was well known as rich and luxurious, with usually very extravagant designs. Unique Venetian furniture types included the divani da portego, and long rococo couches and pozzetti, objects meant to be placed against the wall. Bedrooms of rich Venetians were usually sumptuous and grand, with rich damask, velvet, and silk drapery and curtains, and beautifully carved rococo beds with statues of putti, flowers, and angels.[174] Venice was especially known for its girandole mirrors, which remained among, if not the, finest in Europe. Chandeliers were usually very colourful, using Murano glass to make them look more vibrant and stand out from others; and precious stones and materials from abroad were used, since Venice still held a vast trade empire. Lacquer was very common, and many items of furniture were covered with it, the most noted being lacca povera (poor lacquer), in which allegories and images of social life were painted. Lacquerwork and Chinoiserie were particularly common in bureau cabinets.[175]

Glass

[edit]

Venice is known for its ornate glass-work, known as Venetian glass, which is world-renowned for being colourful, elaborate, and skilfully made. Many of the important characteristics of these objects had been developed by the 13th century. Toward the end of that century, the centre of the Venetian glass industry moved to Murano, an offshore island in Venice. The glass made there is known as Murano glass.

Byzantine craftsmen played an important role in the development of Venetian glass. When Constantinople was sacked in the Fourth Crusade in 1204, some fleeing artisans came to Venice; when the Ottomans took Constantinople in 1453, still more glassworkers arrived. By the 16th century, Venetian artisans had gained even greater control over the colour and transparency of their glass, and had mastered a variety of decorative techniques. Despite efforts to keep Venetian glassmaking techniques within Venice, they became known elsewhere, and Venetian-style glassware was produced in other Italian cities and other countries of Europe.

Some of the most important brands of glass in the world today are still produced in the historical glass factories on Murano. They are: Venini, Barovier & Toso, Pauly, Millevetri, and Seguso.[176] Barovier & Toso is considered one of the 100 oldest companies in the world, formed in 1295.

In February 2021, the world learned that Venetian glass trade beads had been found at three prehistoric Inuit sites in Alaska, including Punyik Point. Uninhabited today, and located 1 mile (1.6 km) from the Continental Divide in the Brooks Range, the area was on ancient trade routes from the Bering Sea to the Arctic Ocean. From their creation in Venice, researchers believe the likely route these artifacts traveled was across Europe, then Eurasia and finally over the Bering Strait, making this discovery "the first documented instance of the presence of indubitable European materials in prehistoric sites in the western hemisphere as the result of overland transport across the Eurasian continent." After radiocarbon dating materials found near the beads, archaeologists estimated their arrival on the continent to sometime between 1440 and 1480, predating Christopher Columbus.[177] The dating and provenance has been challenged by other researchers who point out that such beads were not made in Venice until the mid-16th century and that an early 17th century French origin is possible.[178][179]

Festivals

[edit]The Carnival of Venice is held annually in the city, It lasts for around two weeks and ends on Shrove Tuesday. Venetian masks are worn.

The Venice Biennale is one of the most important events in the arts calendar. In 1895 an Esposizione biennale artistica nazionale (biennial exhibition of Italian art) was inaugurated.[180] In September 1942, the activities of the Biennale were interrupted by the war, but resumed in 1948.[181]

The Festa del Redentore is held in mid-July. It began as a feast to give thanks for the end of the plague of 1576. A bridge of barges is built connecting Giudecca to the rest of Venice, and fireworks play an important role.

The Venice Film Festival (Italian: Mostra Internazionale d'Arte Cinematografica di Venezia) is the oldest film festival in the world.[182] Founded by Count Giuseppe Volpi di Misurata in 1932 as the Esposizione Internazionale d'Arte Cinematografica, the festival has since taken place every year in late August or early September on the island of the Lido. Screenings take place in the historic Palazzo del Cinema on the Lungomare Marconi. It is one of the world's most prestigious film festivals and is part of the Venice Biennale.

Music

[edit]

The city of Venice in Italy has played an important role in the development of the music of Italy. The Venetian state (the medieval Republic of Venice) was often popularly called the "Republic of Music", and an anonymous Frenchman of the 17th century is said to have remarked that "In every home, someone is playing a musical instrument or singing. There is music everywhere."[183]

During the 16th century, Venice became one of the most important musical centres of Europe, marked by a characteristic style of composition (the Venetian school) and the development of the Venetian polychoral style under composers such as Adrian Willaert, who worked at St Mark's Basilica. Venice was the early centre of music printing; Ottaviano Petrucci began publishing music almost as soon as this technology was available, and his publishing enterprise helped to attract composers from all over Europe, especially from France and Flanders. By the end of the century, Venice was known for the splendor of its music, as exemplified in the "colossal style" of Andrea and Giovanni Gabrieli, which used multiple choruses and instrumental groups. Venice was also the home of many noted composers during the baroque period, such as Antonio Vivaldi, Tomaso Albinoni, Ippolito Ciera, Giovanni Picchi, and Girolamo Dalla Casa, to name but a few.

Orchestras

[edit]Venice is the home of numerous orchestras such as, the Orchestra della Fenice, Rondò Veneziano, Interpreti Veneziani, and Venice Baroque Orchestra.

Cinema, media, and popular culture

[edit]

The city has been the setting or chosen location of numerous films, games, works of fine art and literature (including essays, fiction, non-fiction, and poems), music videos, television shows, and other cultural references.[186]

One example of this is Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade.[187]

Another example of this is Jojo's Bizarre Adventure part 2: Battle Tendency

Photography

[edit]Fulvio Roiter was the pioneer in artistic photography in Venice,[188] followed by a number of photographers whose works are often reproduced on postcards, thus reaching a widest international popular exposure.[citation needed] Luca Zordan, a New York City based photographer was born in Venice.[189]

Cuisine

[edit]Venetian cuisine is characterized by seafood, but also includes garden products from the islands of the lagoon, rice from the mainland, game, and polenta. Venice is not known for a particular cuisine of its own: it combines local traditions with influences stemming from age-old contacts with distant countries.[clarification needed] These include sarde in saór (sardines marinated to preserve them for long voyages); bacalà mantecato (a recipe based on Norwegian stockfish and extra-virgin olive oil); bisàto (marinated eel); risi e bisi – rice, peas and (unsmoked) bacon;[190] fegato alla veneziana, Venetian-style veal liver; risòto col néro de sépe (risotto with cuttlefish, blackened by their own ink); cichéti, refined and delicious tidbits (akin to tapas); antipasti (appetizers); and prosecco, an effervescent, mildly sweet wine.