A City of Sadness

| A City of Sadness | |

|---|---|

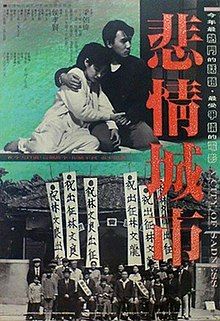

Taiwanese film poster | |

| Chinese | 悲情城市 |

| Literal meaning | City of sadness |

| Hanyu Pinyin | bēiqíng chéngshì |

| Directed by | Hou Hsiao-hsien |

| Written by | Chu T’ien-wen Wu Nien-jen |

| Produced by | Chiu Fu-sheng |

| Starring | Tony Leung Chiu-wai Chen Sung-young Jack Kao Li Tian-lu |

| Cinematography | Chen Hwai-en |

| Edited by | Liao Ching-song |

| Music by | S.E.N.S. |

Production company | 3-H Films |

| Distributed by | Era Communications (Int'l rights) |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 157 minutes |

| Country | Taiwan |

| Languages | Taiwanese Mandarin Japanese Cantonese Shanghainese |

A City of Sadness (Chinese: 悲情城市; pinyin: Bēiqíng chéngshì) is a 1989 Taiwanese historical drama directed by Hou Hsiao-hsien. It tells the story of a family embroiled in the "White Terror" that was wrought on the Taiwanese people by the Kuomintang government (KMT) after their arrival from mainland China in the late 1940s, during which thousands of Taiwanese and recent emigres from the Mainland were rounded up, shot, and/or sent to prison. The film was the first to deal openly with the KMT's authoritarian misdeeds after its 1945 takeover of Taiwan, which had been relinquished following Japan's defeat in World War II, and the first to depict the February 28 Incident of 1947, in which thousands of people were massacred by the KMT.

A City of Sadness was the first (of three) Taiwanese films to win the Golden Lion award at the Venice Film Festival, and is often considered Hou's masterpiece.[1] The film was selected as the Taiwanese entry for the Best Foreign Language Film at the 62nd Academy Awards, but was not accepted as a nominee.[2]

This film is regarded as the second installment in the Wu Nien-jen trilogy as well as the first installment in a loose trilogy of Hsiao-Hsien's films that deal with Taiwanese history, which also includes The Puppetmaster (1993) and Good Men, Good Women (1995). These films are collectively called the "Taiwan Trilogy" by academics and critics.[3]

Plot

[edit]The film follows the Lin family in a coastal town near Taipei, Taiwan from 1945 to 1949, the period after the end of 50 years of Japanese colonial rule and before the establishment of a government-in-exile in Taiwan by Chiang Kai-shek's Nationalist Kuomintang forces once the Communist army captured mainland China.

The film starts on August 15, 1945, with the voice of Emperor Hirohito announcing Japan's unconditional surrender. When Taiwan regained its sovereignty, people were full of joy. A large number of people from the mainland went to Taiwan such as Kuomintang troops, gangsters and people with socialist ideas. Meanwhile, Lin Wen-hsiung, who runs a bar called "Little Shanghai" and is the eldest of the Lin's four sons, awaits the birth of his child. The second son disappeared in the Philippines during the war. The fourth and youngest son, Wen-ching, is a doctor and photographer with leftist leanings who became deaf following a childhood accident; he is close friends with Hiroe and Hiroe's sister, Hiromi.

The third son, Lin Wen-liang, had been recruited by the Japanese to Shanghai as an interpreter. After the defeat of Japan, he was arrested by the Kuomintang government on charges of treason. As a result, his mental condition was stimulated and he had been in hospital since he returned to Taiwan. When he recovered, he met his old acquaintance. He began to engage in illegal activities, including the theft of Japanese currency notes and a smuggling operation run by Shanghainese gangsters. Wen-hsiung eventually learns of this and stops Wen-liang. However, this leads the Shanghainese mob to arrange for Wen-liang's imprisonment on false charges of collaboration with the Japanese. While in prison, Wen-liang is tortured and suffers brain damage as a result.

The February 28 Incident of 1947 occurs, in which thousands of Taiwanese people are massacred by Kuomintang troops. The Lin family follows announcements related to the event via radio, in which Chen Yi, the chief executive of Taiwan, declares martial law to suppress dissenters. The wounded pour into the neighborhood clinic, and Wen-ching is arrested but eventually released. Hiroe heads for the mountains to join the leftist guerillas. Wen-ching expresses his desire to join Hiroe, but Hiroe convinces Wen-ching to return and marry Hiromi, who loves him.

When Lin Wen-hsiung is gambling at a casino one day, a fight breaks out with one of the Shanghainese who previously framed Wen-liang. This results in Wen-hsiung being shot and killed by a Shanghainese mafia member. Following Wen-hsiung's funeral, Wen-ching and Hiromi marry at home, and Hiromi later bears a child. The couple supports Hiroe's resistance group, but the guerilla forces are defeated and executed. They manage to inform Wen-ching of the fact and encourage him to escape, but Hiromi later recounts that they did not have anywhere to go. As a result, Wen-ching is soon arrested by the Kuomintang for his involvement with the guerillas, and there are only Hiromi and her son left at home.[citation needed]

Historical background

[edit]During the Japanese colonial period (1895–1945), Taiwan had limited contact with mainland China. Thus when the control of Taiwan was given to the Republic of China (ROC) led by the Kuomintang (KMT) government at the end of the Second World War, the people on Taiwan faced major political, social, cultural and economic adjustment. Cultural and social tension built up between the Taiwanese and mainlanders during these years. Political distrust was also intensifying between Taiwanese elites and the Provincial Administration headed by Governor Chen Yi. Meanwhile in the late 1940s, the Nationalist government was engaged in a civil war against the Communists on the mainland. The Chinese economy deteriorated rapidly and the post-war economic situation in Taiwan worsened each day. An increasing number of illegal activities took place across the Taiwan Strait and social disturbances, as a result of unemployment, food shortages, poverty, and housing issues, became imminent.[4]

The February 28th Incident

[edit]One of the restrictions implemented at the time was the ban of cigarette trading. The immediate story begins in the front of a tea house in Taipei the day before, on February 27, 1947, when agents from the Tobacco Monopoly Bureau confiscated a Taiwanese female cigarette vendor's illegal cigarettes as well as her money, and then beat her over the head with a pistol while attempting to arrest her. An angry crowd swarmed the agents, prompting one official to open fire on the crowd, killing a bystander. The news triggered mass protests the following morning on February 28; more people were killed by the police and it quickly turned into a large-scale riot.[5] While many local Taiwanese took this as an opportunity to seek revenge on mainlanders, Governor Chen Yi issued martial law and requested Nationalist troops to be sent over from mainland to suppress the incident. For the following 38 years, Taiwan was placed under martial law in a period that is now known as the "White Terror" period. Consequently, a generation of Taiwanese local elites were arrested and killed. It was estimated that between 10,000 and 20,000 people died as a result of the 2/28 incident, with more and more people dying or going missing during the White Terror. The trauma of 2/28 haunted Taiwan's politics and society and soured the relationship between the Taiwanese and mainlanders for several decades.[4]

Cast

[edit]- Tony Leung Chiu-wai as Lin Wen-ching (林文清), fourth brother, a doctor and photographer. Wen-ching is the youngest son in the Lin family. He is deaf-mute because of an accident in his childhood. He communicates with others mainly by writing, especially with Hiromi. He is arrested following the 2/28 event. After he is released, he does two things. First, he delivers the final messages of executed cellmates. Second, he goes to find Hiroe and wants to join him as a revolutionary, however, he is convinced by Hiroe and goes back home to marry Hiromi. Wen-heung opens a photo studio so Wen-ching can support Hiroe, and after the guerilla forces are defeated, Wen-ching gets arrested and never comes back, leaving Hiromi and their child.

- Chen Sung-young as Lin Wen-heung (林文雄), eldest brother, and owner of a trading company and restaurant. After his restaurant is closed down following the 2/28 event, he falls into drinking and gambling, and is eventually shot to death in a spur of the moment revenge attack for Wen-leung.

- Jack Kao as Lin Wen-leung (林文良), third brother, traumatised by his time in the war. After his release from hospital, he goes into business with Shanghai gangsters. After causing them more trouble than he is worth, Wen-leung is framed by the gangsters and goes to prison where he is beaten and suffers brain damage before being released.

- Li Tian-lu as Lin Ah-lu (林阿祿), patriarch of the Lin family.

- Xin Shufen as Hiromi (Japanese pronunciation of her Chinese name: 吳寬美), sister of Hiroe, and is a nurse in the hospital. She knows Wen-ching through her brother Hiroe. She usually communicates with Wen-ching by writing. After she quits her job at the hospital, she marries Wen-ching after he is released from prison and they have a child.

- Wu Yi-fang as Hiroe (Japanese pronunciation of his Chinese name: 吳寬榮), friend of Wen-Ching, brother of Hiromi and a school teacher. A progressive. Because the Taiwan government arrested a large number of progressives and killed innocent people indiscriminately, he establishes an anti-government organization in the mountains. However, they are defeated and arrested at the end.

- Nakamura Ikuyo as Shizuko

- Chan Hung-tze as Mr. Lin. A progressive friend of Hiromi.

- Wu Nien-jen as Mr. Wu.

- Zhang Dachun as Reporter Ho.

- Tsai Chen-nan as singer (cameo appearance).

Music

[edit]| No. | Name |

|---|---|

| 01 | 悲情城市~A City Of Sadness |

| 02 | Hiromi~Flute Solo |

| 03 | 文清のテーマ |

| 04 | Hiromiのテーマ |

| 05 | 悲情城市~Variation 2 |

| 06 | 凛~Dedicated To Hou Hsiao-Hsien |

Sourced from Xiami Music.[6]

Production

[edit]A City of Sadness was filmed on location in Jiufen, a former Japanese and declined gold mining town that continued to operate in the postwar period until the 1960s. Jiufen is located in the northeast of Taiwan, an area isolated from the rest of Taipei County and Yilan County. There are only rough county roads and a local commuter railway line connecting Jiufen to the outside world, which designated a low priority for urban revitalization and land development.[citation needed] Jiufen's hillside communities were constructed before the modern zoning codes were put in place, and therefore provided a small Taiwanese town feeling and atmosphere that symbolizes the historical period that is presented in the plot of A City of Sadness.[7]

Hou remembers Jiufen fondly as he traveled to Jiufen through a tourist gaze when he was young. The shooting of the scenes of train travel to Jiufen particularly evoked his nostalgic rhetoric and joyful memories of a high school trip to Jiufen with his school friends. Hou noted that the train in Taiwan is a very important mode of transportation and he would ride the train a lot. It is very hard for him to forget the connection between him and the trains, so the train tracks appear multiple times in the film.[7]

Background

[edit]By the 1980s, the New Taiwanese Cinema movement was moving towards not just creating films for the people of Taiwan, but also for a larger, international audience. Directors Hou Hsiao-hsien and Edward Yang noted that they wanted to emulate the popularity of Hong Kong cinema, which revolved around high quality productions with strong star power to back it up.[3] In A City of Sadness, Hou relied primarily on foreign investment, particularly from Japan. Japanese technology, techniques, and facilities were used in the post-production and resulted in what critic and producer Zhan Hongzhi described as an aspect of "high-quality" that could draw in international viewership.[3] Another aspect of this plan was star power, reflected in one of the principal characters, Wen-ching, being played by then rising Hong Kong film star Tony Leung.[3] The intention behind this was to increase Hong Kong and Overseas Chinese viewership. The film also used an array of different languages, chiefly Taiwanese Hokkien, Cantonese, Japanese, and Shanghainese as a way to promote the cultural diversity of the cast and reflectively, of Taiwan to a global audience, which stands in contrast to many earlier films being only in Mandarin Chinese, due to the governments promotion of Mandarin as the national language.[3]

Conceptualization

[edit]Hou Hsiao-hsien was interested in creating a film that could tell a story about a family, specifically during the 228 Incident and the White Terror by a few reasons. He cited how the death of Chiang Ching-kuo in 1988 and the lifting of martial law the year prior made it an appropriate time to address the 228 Incident, which Hou felt had been covered up by the government. He noted how books were not available on the subject and he wanted to provide a vantage point about the story through the lens of a family.[8]

Hou Hsiao-hsien wrote:

"Everybody knew about the 228 Incident. Nobody would say anything, at least in public, but behind closed doors everyone was talking about it, especially in the Tangwai Movement [..] The 228 Incident was already known, so I was more interested in filming a time of transition, and the changes in a family during a change in regime. This was the main thing I wanted to capture… There's been too much political intervention. We should go back to history itself for a comprehensive reflection, but politicians like to use this tragedy as an ATM, making a withdrawal from it whenever they want. It's awful. So no matter what point of view I took with the film, people would still criticize it. I was filming events that were still taboo, I had a point of view, and no matter what, I was filming from the point of view of people and a family… Of course it's limited by the filmmaker's vision and attitude. I can only present a part of the atmosphere of the time."[8]

According to scriptwriter Chu Tien-Wen's book, the original premise of the film was the reunion of an ex-gangster (which Hou Hsiao-Hsien intended to cast Chow Yun-fat for the role) and his former lover (supposedly played by Yang Li-Hua, the top Taiwanese Opera actress in real-life) in 1970s. Hou and Chu then extended the story to involve substantial flashbacks of the calamity of the woman's family in late 1940s (where the woman was the teenage daughter of Chen Song-Yong's character). They then abandoned the former premise and instead focused on the 1940s' story.

Film techniques

[edit]The movie includes many Chinese dialects, such as Southern Min, Cantonese and Shanghainese, which make this film pellucid for different groups of people. Ming-Yeh T. Rawnsley explains that "by representing the political reality of the late 1940s indirectly, A City of Sadness deals with the past, but is not trapped by the past, and is able to achieve a sense of objectiveness and authenticity."[4] The use of dialects and historical facts can make audiences have a connection to characters within the film, and ensure the objectiveness and authenticity. The film also functions as a form of resistance as those with less power are able to diminish claims by other classes.

Wen-ching's deafness and muteness began as an expedient way to disguise Tony Leung's inability to speak Taiwanese (or Japanese—the language taught in Taiwan's schools during the 51-year Japanese rule), but wound up being an effective means to demonstrate the brutal insensitivity of Chen Yi's ROC administration.[9] As he communicated through other means (photographs, pen and paper) he is often playing the role of an observer. His inability to speak could mirror Taiwan being silenced by its oppressors.

Sound plays an important role in the film as the opening scene is shot in darkness, with the only sound being Emperor Hirohito on the radio broadcast. Throughout the film, the use of Japanese language is cultural, as it represents the experiences of the Taiwanese and their cultural identity. Most of the characters would not be able to understand much Japanese as they would not have lived through 51 years of Japanese rule. This is why the native characters speak Taiwanese with some Japanese words mixed into their speech.[10]

Reception and impact

[edit]Critical reception

[edit]A City of Sadness was a major commercial success in Taiwan, but critics were largely ambivalent toward the work. Having been advertised as a film about the February 28 Incident but never explicitly depicting the event, the film was consequently criticized as politically ambiguous, as well as overly difficult to follow.[11] It was also criticized for not depicting the events of February 28 well, instead presenting the events in a subtle and elliptical manner.[12] It is now widely considered a masterpiece,[13] and has been described as "probably the most significant film to have emerged out of Taiwan's New Cinema."[11]

Richard Brody of The New Yorker argued, "Hou's extraordinarily controlled and well-constructed long takes blend revelation and opacity; his favorite trope is to shoot through doorways, as if straining to capture the action over impassable spans of time."[14] In Time Out, Tony Rayns wrote, "Loaded with detail and elliptically structured to let viewers make their own connections, [...] Hou turns in a masterpiece of small gestures and massive resonance; once you surrender to its spell, the obscurities vanish."[15] Jonathan Rosenbaum lauded Hou as "a master of long takes and complex framing, with a great talent for passionate (though elliptical and distanced) storytelling."[16] In the Chicago Tribune, Dave Kehr declared, "A City of Sadness is a great film, one that will be watched as long as there are people who care about the movies as an art."[17]

The review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes reported that 100% of critics have given the film a positive review based on 13 reviews, with an average rating of 9.30/10.[18] In the British Film Institute's 2012 Sight & Sound poll, 14 critics and two directors named A City of Sadness one of the ten greatest films ever made, placing it at #117 in the critics' poll and #322 in the directors' poll.[19]

History, trauma, and reconciliation

[edit]Critics have noted how this film (as well as the other 2 films that form the trilogy) started a larger discussion into memory and reconciliation for the 228 Incident and the White Terror on Taiwan. Sylvia Lin commented that "literary, scholarly, historical, personal, and cinematic accounts of the past have mushroomed, as the people in Taiwan feel the urgent need to remember, reconstruct, and rewrite that part of their history.”[20] June Yip noted that the Taiwan Trilogy marked a “autobiographical impulse” to reclaim the history that was now acceptable with the lifting of martial law.[21] Another critic, Jean Ma, also noted the method of displaying trauma by Hou felt "real" and could connect to global audiences everywhere from the "Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa, the desaparecidos of Argentina, and the Armenian massacre as instances in which memory bears the ethical burden of a disavowed or denied history."[21]

Resurgence of Taiwanese Hokkien (Taiyu) in film

[edit]A City of Sadness has been touted as one of the few films to bring Taiwanese Hokkien to prominence and to a global audience. The usage of Taiwanese Hokkien in the film has been noted to be in direct conflict with the then-rule regarding national language in Taiwan. The Taiwanese language policy about promoting Mandarin made making films in other minority dialects and languages limited to only a third of the total script. A City of Sadness however, was filmed mostly in Taiwanese Hokkien. Hou Hsiao-hsien's film was allowed by the Government Information Office (the office responsible for government censorship/media) to send a copy of the rough cut to Japan for post-production where it was processed and sent directly to the Venice Film Festival without being authenticated by Taiwanese censors from the GIC.[22] The winning of the Golden Lion and Golden Horse Awards marked a first for Chinese-speaking films, but also were controversial, since A City of Sadness violated then rules about national language usage in films. The success of the film however, renewed interest in Taiwanese Hokkien and became part of the Taiyu Language Movement and started a resurgence of films from Taiwan that utilized minority languages such as Hakka alongside other Taiwanese indigenous languages.

Contemporary references

[edit]The term "City Of Sadness" has been used to describe the state of Hong Kong after the 2014 Umbrella Movement by scholars. Academic Tina L. Rochelle has associated the term with how Hong Kong's trajectory mirrors the trajectory of Taiwan during the 228 Incident and the White Terror.[23] Much like in the case of the 228 Incident, the Umbrella movement was fueled by building resentment of the way Hong Kong citizens were being treated after the 1997 handover of Hong Kong to the Peoples Republic of China. The cause of anger with citizens was the deterioration of freedoms and rights, the increased feeling of policing, and the imposition of a foreign power's sovereignty over a newly integrated location. This is a characteristic Rochelle highlights as similar in both Taiwan and Hong Kong and is what makes Hong Kong a "modern City of Sadness."[23]

Awards and nominations

[edit]- 46th Venice Film Festival

- Won: Golden Lion[24]

- Won: UNESCO Prize

- 1989 Golden Horse Film Festival

- Won: Best Director – Hou Hsiao-hsien

- Won: Best Leading Actor – Sung Young Chen

- Nominated: Best Film

- Nominated: Best Screenplay – Chu T’ien-wen, Wu Nien-jen

- Nominated: Best Editing – Liao Ching-song

- 1989 Kinema Junpo Awards

- Won: Best Foreign Language Film – Hou Hsiao-hsien

- 1991 Mainichi Film Concours

- Won: Best Foreign Language Film – Hou Hsiao-hsien

- 1991 Independent Spirit Awards

- Nominated: Best Foreign Film – Hou Hsiao-hsien

- 1991 Political Film Society

- Won: Special Award

See also

[edit]- List of submissions to the 62nd Academy Awards for Best Foreign Language Film

- List of Taiwanese submissions for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film

References

[edit]- ^ Xiao, Zhiwei; Zhang, Yingjin (2002). Encyclopedia of Chinese Film. Routledge. p. 190. ISBN 1134745540.

- ^ Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

- ^ a b c d e Trauma and Cinema: Cross-Cultural Explorations. Hong Kong University Press. 2008. ISBN 978-962-209-624-0. JSTOR j.ctt2jc7kk.

- ^ a b c Rawnsley, Ming-Yeh T. (2011). "Cinema, Historiography, and Identities in Taiwan: Hou Hsiao-Hsien's A City of Sadness". Asian Cinema. 22 (2): 196–213. doi:10.1386/AC.22.2.196_1. ISSN 1059-440X.

- ^ Shattuck, Thomas J. "Taiwan's White Terror: Remembering the 228 Incident". Foreign Policy Research Institute. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- ^ "A City of Sadness by S.E.N.S." Xiami Music.

- ^ a b Lo, Dennis (2020). "A Home in Becoming: Forging Taiwan's Imagined Community in Jiufen". The Authorship of Place: A Cultural Geography of the New Chinese Cinemas. Oxford University Press. pp. 98–117. doi:10.5790/hongkong/9789888528516.003.0005. ISBN 9789888180028. S2CID 236874268.

- ^ a b "Reality in Long Shots: A CITY OF SADNESS | Austin Asian American Film Festival | Online Shorts Festival June 11–17, 2020". Archived from the original on 15 June 2020. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- ^ Berry, Michael (October 2005). Speaking in Images: Interviews with Contemporary Chinese Filmmakers. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-13330-2.

- ^ Rawnsley, Ming-Yeh. "Rawnsley, M.T. (2012). Cinema, Identity, and Resistance: Comparative Perspectives on A City of Sadness and The Wind that Shakes the Barley".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b "A City of Sadness". Harvard Faculty of Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on 25 October 2018. Retrieved 6 February 2017.

- ^ Linden, Sheri (23 August 2019). "'A City Of Sadness': Hou Hsiao-Hsien's Historical Tragedy Remains A Masterpiece 30 Years Later". SupChina. Archived from the original on 29 April 2022. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- ^ Shaw, Tristan (28 March 2015). "Taiwanese director Hou Hsiao-hsien captures life's big, small moments". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 6 February 2017. "In "A City of Sadness," widely considered a masterpiece,"

- ^ Brody, Richard. "A City of Sadness". The New Yorker. Retrieved 6 February 2017.

- ^ Rayns, Tony. "A City of Sadness". Time Out. Retrieved 6 February 2017.

- ^ Rosenbaum, Jonathan. "A City of Sadness". Chicago Reader. Retrieved 6 February 2017.

- ^ Kehr, Dave (22 June 1990). "Taiwanese 'Sadness' Filmmaking At Its Best". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 6 February 2017.

- ^ "Bei qing cheng shi (A City of Sadness) (1989)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Retrieved 20 July 2023.

- ^ ""City of Sadness, A" (1989)". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 20 August 2012. Retrieved 3 June 2015.

- ^ Lin, Sylvia Li-chun (2007). Representing Atrocity in Taiwan: The 2/28 Incident and White Terror in Fiction and Film. Columbia University Press. doi:10.7312/lin-14360. ISBN 9780231512817. JSTOR 10.7312/lin-14360.

- ^ a b Ma, Jean (2010). Melancholy Drift: Marking Time in Chinese Cinema. Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 978-988-8028-05-4. JSTOR j.ctt1xcs2b.

- ^ Zhang, Yingjin (2013). "Articulating Sadness, Gendering Space: The Politics and Poetics of Taiyu Films from 1960s Taiwan". Modern Chinese Literature and Culture. 25 (1): 1–46. ISSN 1520-9857. JSTOR 42940461.

- ^ a b Rochelle, Tina L. (2015). "Diversity and Trust in Hong Kong: An Examination of Tin Shui Wai, Hong Kong's 'City of Sadness'". Social Indicators Research. 120 (2): 437–454. doi:10.1007/s11205-014-0592-z. ISSN 0303-8300. JSTOR 24721122. S2CID 145079416.

- ^ "The awards of the Venice Film Festival". Retrieved 6 March 2011.

Further reading

[edit]- Reynaud, Bérénice (2002). A City of Sadness. London: British Film Inst. ISBN 9780851709307.

External links

[edit]- A City of Sadness at IMDb

- A City of Sadness at Rotten Tomatoes

- ‹The template AllMovie title is being considered for deletion.› A City of Sadness at AllMovie

- 1989 films

- Taiwanese war drama films

- Taiwanese-language films

- 1980s Mandarin-language films

- 1980s war drama films

- Films set in the 1940s

- Golden Lion winners

- Films whose director won the Best Director Golden Horse Award

- Films directed by Hou Hsiao-hsien

- Films with screenplays by Wu Nien-jen

- Films with screenplays by Chu T’ien-wen

- 1989 crime drama films

- Films about the White Terror (Taiwan)

- Films scored by S.E.N.S.