Chinese emigration

| Chinese emigration | |

|---|---|

Typical grocery store on 8th Avenue in one of the Brooklyn Chinatowns (布鲁克林華埠) on Long Island, New York. New York City's multiple Chinatowns in Queens (法拉盛華埠), Manhattan (紐約華埠), and Brooklyn are thriving as traditionally urban enclaves, as large-scale Chinese immigration continues into New York,[1][2][3][4] with the largest metropolitan Chinese population outside Asia,[5] The New York metropolitan area contains the largest ethnic Chinese population outside of Asia, comprising an estimated 893,697 uniracial individuals as of 2017.[6] |

Waves of Chinese emigration have happened throughout history. They include the emigration to Southeast Asia beginning from the 10th century during the Tang dynasty, to the Americas during the 19th century, particularly during the California gold rush in the mid-1800s; general emigration initially around the early to mid 20th century which was mainly caused by corruption, starvation, and war due to the Warlord Era, the Second Sino-Japanese War and the Chinese Civil War; and finally elective emigration to various countries. Most emigrants were peasants and manual laborers, although there were also educated individuals who brought their various expertises to their new destinations.

Chronology of historical periods

[edit]

11th century BCE to 3rd century BCE

[edit]- The Zhou dynasty overthrew the Shang dynasty in 1046 BCE. This conquest marked the beginning of the Zhou rule and the expansion of their territorial control.[7]

- Western Zhou: The Zhou people engaged in active military campaigns to expand their territory. As they conquered new regions, there was likely a movement of people to settle and administer these newly acquired lands.[8]

- Eastern Zhou period: The Eastern Zhou period is characterized by the Spring and Autumn period (770–476 BCE) and the Warring States period (475–221 BCE). During this time, the exchange of ideas and cultures between different states led to migration of scholars, artisans, and officials.[7]

- From the Han dynasty onwards, Chinese military and agricultural colonies (Chinese: 屯田) were established at various times in the Western Regions, which in the early periods were lands largely occupied by an Indo-European people called the Tocharians.

10–15th century

[edit]- Many Chinese merchants chose to settle down[when?] in the Southeast Asian ports such as Champa, Cambodia, Java, and Sumatra, and married the native women. Their children carried on trade.[9][10]

- Borneo: Many Chinese lived in Borneo as recorded by Zheng He.

- Cambodia: Envoy of Yuan dynasty, Zhou Daguan (Chinese: 周达观) recorded in his The Customs of Chenla (Chinese: 真腊风土记), that there were many Chinese, especially sailors, who lived there. Many intermarried with the local women.

- Champa: the Daoyi Zhilüe documents Chinese merchants who went to Cham ports in Champa, married Cham women, to whom they regularly returned to after trading voyages.[11] A Chinese merchant from Quanzhou, Wang Yuanmao, traded extensively with Champa, and married a Cham princess.[12]

- Han Chinese settlers came during the Malacca Sultanate in the early 15th century. The friendly diplomatic relations between China and Malacca culminated during the reign of Sultan Mansur Syah, who married the Chinese princess Hang Li Po. A senior minister of state and five hundred youths and maids of noble birth accompanied the princess to Malacca.[13] Admiral Zheng He had also brought along 100 bachelors to Malacca.[14] The descendants of these two groups of people, mostly from Fujian province, are called the Baba (men) and Nyonya (women).

- Java: Zheng He's 鄭和 compatriot Ma Huan (Chinese: 馬歡) recorded in his book Yingya Shenglan (Chinese: 瀛涯胜览) that large numbers of Chinese lived in the Majapahit Empire on Java, especially in Surabaya (Chinese: 泗水). The place where the Chinese lived was called New Village (新村), with many originally from Canton, Zhangzhou and Quanzhou.

- Ryūkyū Kingdom: Many Chinese moved to Ryukyu to serve the government or engage in business during this period. The Ming dynasty sent from Fujian 36 Chinese families at the request of the Ryukyuan King to manage oceanic dealings in the kingdom in 1392 during the Hongwu Emperor's reign. Many Ryukyuan officials were descended from these Chinese immigrants, being born in China or having Chinese grandfathers.[15] They assisted in the Ryukyuans in advancing their technology and diplomatic relations.[16][17][18]

- Siam: According to the clan chart of family name Lim, Gan, Ng, Khaw, Cheah, many Chinese traders lived there. They were amongst some of the Siamese envoys sent to China.

- In 1405, under the Ming dynasty, Tan Sheng Shou, the Battalion Commander Yang Xin (Chinese: 杨欣) and others were sent to Java's Old Port (Palembang; 旧港) to bring the absconder Liang Dao Ming (Chinese: 梁道明) and others to negotiate pacification. He took his family and fled to live in this place, where he remained for many years. Thousands of military personnel and civilians from Guangdong and Fujian followed him there and chose Dao Ming as their leader.

- On Lamu Island off the Kenyan coast, local oral tradition maintains that 20 shipwrecked Chinese sailors, possibly part of Zheng's fleet, washed up on shore there hundreds of years ago. Given permission to settle by local tribes after having killed a dangerous python, they converted to Islam and married local women. Now, they are believed to have just six descendants left there; in 2002, DNA tests conducted on one of the women confirmed that she was of Chinese descent. Her daughter, Mwamaka Sharifu, later received a PRC government scholarship to study traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) in China.[19][unreliable source?][20] On Pate Island, Frank Viviano described in a July 2005 National Geographic article how ceramic fragments had been found around Lamu which the administrative officer of the local Swahili history museum claimed were of Chinese origin, specifically from Zheng He's voyage to East Africa. The eyes of the Pate people resembled Chinese and Famao and Wei were some of the names among them which were speculated to be of Chinese origin. Their ancestors were said to be from indigenous women who intermarried with Chinese Ming sailors when they were shipwrecked. Two places on Pate were called "Old Shanga", and "New Shanga", which the Chinese sailors had named. A local guide who claimed descent from the Chinese showed Frank a graveyard made out of coral on the island, indicating that they were the graves of the Chinese sailors, which the author described as "virtually identical", to Chinese Ming dynasty tombs, complete with "half-moon domes" and "terraced entries".[21][better source needed]

- According to Melanie Yap and Daniel Leong Man in their book Colour, Confusions and Concessions: the History of Chinese in South Africa, Chu Ssu-pen, a Yuan mapmaker, had southern Africa drawn on one of his maps in 1320.[dubious – discuss] Ceramics found in Zimbabwe and South Africa dated back to the era of the Song dynasty in China.[dubious – discuss] Some tribes to Cape Town's north claimed descent from Chinese sailors during the 13th century, their physical appearance is similar to Chinese with paler skin and a Mandarin-sounding tonal language; they call themselves Awatwa ("abandoned people").[22][better source needed] Most early Chinese ceramics and coins found in Africa are not from Chinese mariners or traders, but were carried by earlier Southeast Asian Austronesian trade ships which established routes to the western Indian Ocean from as early as the 5th century AD and colonized Madagascar.[23]

15th–19th century

[edit]- When the Ming dynasty in China fell, Chinese refugees fled south and extensively settled in the Cham lands and Cambodia.[24] Most of these Chinese were young males, and they took Cham women as wives. Their children identified more with Chinese culture. This migration occurred in the 17th and 18th centuries.[25]

- Early European colonial powers in Asia encountered Chinese communities already well-established in various locations. The Kapitan Cina in various places was the representative of such communities towards the colonial authorities.

- The Qing conquest of the Ming caused the Fujian refugees of Zhangzhou to resettle on the northern part of the Malay peninsula and Singapore, while those of Amoy and Quanzhou resettled on the southern part of the peninsula. This group forms the majority of the Straits Chinese who were English-educated. Others moved to Taiwan at this time as well.

19th–early 20th century

[edit]

- In the mid-1800s, outbound migration from China increased as a result of the European colonial powers opening up treaty ports.[30]: 137 The British colonization of Hong Kong further created the opportunity for Chinese labor to be exported to plantations and mines.[30]: 137

- Chinese immigrants, mainly from the controlled ports of Fujian and Guangdong provinces, were attracted by the prospect of work in the tin mines, rubber plantations or the possibility of opening up new farmlands at the beginning of the 19th century until the 1930s in British Malaya.

- After Singapore became the capital of the Straits Settlements in 1832, the free trade policy attracted many Chinese merchants from Mainland China to trade, and many settled down in Singapore. Because of booming commerce which required a large labor force, the indentured Chinese coolie trade also appeared in Singapore. Coolies were contracted by traders and brought to Singapore to work. The large influx of coolies into Singapore only stopped after William Pickering became the Protector of Chinese. In 1914, the coolie trade was abolished and banned in Singapore. These populations form the basis of the Chinese Singaporeans.

- Peranakans, or those descendants of Chinese in Southeast Asia for many generations who were generally English-educated were typically known in Singapore as "Laokuh" (老客 – Old Guest) or "Straits Chinese". Most of them paid loyalty to the British Empire and did not regard themselves as "Huaqiao". From the 19th till the mid-20th century, migrants from China were known as "Sinkuh" (新客 – New Guest). A majority of them were coolies, workers on steamboats, etc. Some of them came to Singapore for work, in search of better living conditions or to escape poverty in China. Many of them also escaped to Singapore due to chaos and wars in China during the first half of the 20th century. They came mostly from the Fujian, Guangdong and Hainan provinces and, unlike Peranakans, paid loyalty to China and regarded themselves as "Huaqiao".

- At the end of the 19th century, the Chinese government realized that overseas Chinese could be an asset, a source of foreign investment, and a bridge to overseas knowledge; thus, it encouraged the use of the term "Overseas Chinese" (华侨).[31]

- Among the provinces, Guangdong had historically supplied the largest number of emigrants, estimated at 8.2 million in 1957; about 68% of the total overseas Chinese population at that time. Within Guangdong, the main emigrant communities were clustered in eight districts in the Pearl River Delta (珠江三角洲): four districts known as Sze Yup (四邑; 'four counties'); three counties known as Sam Yup (三邑; 'three counties'); and the district of Zhongshan (中山).[32] Because of its limited arable lands, with much of its terrain either rocky or swampy; Sze Yup was the "pre-eminent sending area" of emigrants during this period.[33] Most of the emigrants from Sze Yup went to North America, making Toishanese a dominant variety of the Chinese language spoken in Chinatowns in Canada and the United States.

- In addition to being a region of major emigration abroad, Siyi (Sze Yup) was a melting pot of ideas and trends brought back by overseas Chinese, (華僑; Huáqiáo). For example, many tong lau in Chikan, Kaiping (Cek Ham, Hoiping in Cantonese) and diaolou (formerly romanized as Clock Towers) in Sze Yup built in the early 20th century featured Qiaoxiang (僑鄉) architecture, i.e., incorporating architectural features from both the Chinese homeland and overseas.[34]

- The first major immigration to America was during the California goldrush of 1848–1855. Many Chinese, as well as people from other Asian countries, were prevented from moving to the United States as part of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. A similar law though less severe in scope was passed in Canada in 1885, imposing a head tax instead of prohibiting immigration to Canada entirely. However, a 1923 law in Canada prohibited Chinese immigration completely. The Chinese Exclusion Act would only be fully repealed in the US in 1965 and in Canada de jure in 1947 but de facto in the 1960s with the opening up of immigration to Canada.

- From 1853 until the end of the 19th century, about 18,000 Chinese were brought as indentured workers to the British West Indies, mainly to British Guiana (now Guyana), Trinidad and Jamaica.[35] Their descendants today are found among the current populations of these countries, but also among the migrant communities with Anglo-Caribbean origins residing mainly in the United Kingdom, the United States and Canada.

- In the first half of the 20th century, war and revolution accelerated the pace of migration out of China.[30]: 127 The Kuomintang and the Communist Party competed for political support from overseas Chinese.[30]: 127–128

- The Kuomintang retreat to Taiwan in 1949 saw an emigration of approximately 2 million mainland Chinese to Taiwan.

- Some Nationalist refugees fled to Singapore, Sarawak, North Borneo and Malaya after the Nationalists lost the civil war to avoid persecution or execution by the Chinese Communist Party.[36]

- Parts of the defeated Nationalist army retreated south and crossed the border into Burma as the People's Liberation Army entered Yunnan.[30]: 65 Beginning in 1953, several rounds of withdrawals of the Nationalist forces and their families were carried out.[30]: 65 In 1960, joint military action by China and Burma expelled the remaining Nationalist forces from Burma, although some went on to settle in the Burma-Thailand borderlands.[30]: 65–66

Modern emigration (late 20th century–present)

[edit]

Due to the political dynamics of the Cold War, there was relatively little migration from the People's Republic of China to southeast Asia from the 1950s until the mid-1970s.[30]: 117

In the early 1960s, about 100,000 people were allowed to enter Hong Kong. In the late 1970s, vigilance against illegal migration to Hong Kong (香港) was again relaxed. Perhaps as many as 200,000 reached Hong Kong in 1979, but in 1980 authorities on both sides resumed concerted efforts to reduce the flow.[citation needed]

More liberalized emigration policies enacted in the 1980s as part of the Opening of China facilitated the legal departure of increasing numbers of Chinese who joined their overseas Chinese relatives and friends. The Four Modernizations program, which required Chinese students and scholars, particularly scientists, to be able to attend foreign education and research institutions, brought about increased contact with the outside world, particularly the industrialized nations.[citation needed]

In 1983, emigration restrictions were eased as a result in part of the economic open-door policy.[citation needed] In 1984, more than 11,500 business visas were issued to Chinese citizens, and in 1985, approximately 15,000 Chinese scholars and students were in the United States alone. Any student who had the economic resources could apply for permission to study abroad. United States consular offices issued more than 12,500 immigrant visas in 1984, and there were 60,000 Chinese with approved visa petitions in the immigration queue.[citation needed]

The signing of the United States–China Consular Convention in 1983 demonstrated the commitment to more liberal emigration policies.[citation needed] Both sides agreed to permit travel for the purpose of family reunification and to facilitate travel for individuals who claim both Chinese and United States citizenship. However, emigrating from China remained a complicated and lengthy process mainly because many countries were unwilling or unable to accept the large numbers of people who wished to emigrate. Other difficulties included bureaucratic delays and, in some cases, a reluctance on the part of Chinese authorities to issue passports and exit permits to individuals making notable contributions to the modernization effort.[citation needed]

New York City's multiple Chinatowns in Queens (法拉盛華埠), Manhattan (紐約華埠), and Brooklyn (布鲁克林華埠) are successful as traditionally urban enclaves, as large-scale Chinese immigration continues into New York during the late 20th century[1][2][38][4] with the largest metropolitan Chinese population outside Asia,[39] The New York metropolitan area contains the largest ethnic Chinese population outside of Asia, comprising an estimated 893,697 uniracial individuals as of 2017.[40] There has additionally been a significant element of illegal Chinese emigration to Brooklyn and Queens, most notably Fuzhou immigrants from Fujian Province and Wenzhou immigrants from Zhejiang Province in mainland China.[41]

A much smaller wave of Chinese immigration to Singapore came after the 1990s, holding the citizenship of the People's Republic of China and mostly Mandarin-speaking Chinese from northern China. The only significant immigration to China has been by the overseas Chinese, who in the years since 1949 have been offered various enticements to repatriate to their homeland.[citation needed]

During the Xi Jinping administration, the number of Chinese asylum seekers abroad increased to 613,000 people as of 2020.[42] As of 2023, illegal Chinese immigration to New York City has accelerated, and its Flushing (法拉盛), Queens neighborhood has become the present-day global epicenter receiving Chinese immigration as well as the international control center directing such migration.[37] Additionally, as of 2024, a significant new wave of Chinese Uyghur Muslims is fleeing religious persecution in northwestern China's Xinjiang Province and seeking religious freedom in New York, and concentrating in Queens.[43]

In the early 2020s, there has been an influx of Chinese migrants using Mexico's northern border to enter America and advance to New York City, termed "ZouXian", translated in English to “walk the line”.[44]

In 2023, China saw the world's largest largest outflow of high-net-worth individuals with over 13,000 emigrating mostly to the U.S., Canada, and Singapore.[45]

See also

[edit]- Chinese Clan Association

- Chinese immigration to Mexico

- Chinese Protectorate

- Haijin (海禁)

- History of Chinese Americans

- History of Chinese immigration to Canada

- Chinese Caribbeans

- History of Chinese Indonesians

- History of Fuzhounese Americans

- Hui

- Immigration to Singapore

- Migration in China

- New immigrants in Hong Kong

- Overseas Chinese

- Peranakan

- Sangley (生理人 or 常來人) ("Sengli": business)

- Tong

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b "Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: 2013 Supplemental Table 2". U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- ^ a b "Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: 2012 Supplemental Table 2". U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Archived from the original on 22 December 2014. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- ^ "Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: 2011 Supplemental Table 2". U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- ^ a b John Marzulli (9 May 2011). "Malaysian man smuggled illegal Chinese immigrants into Brooklyn using Queen Mary 2: authorities". Daily News. New York. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- ^ "Chinese New Year 2012 in Flushing". QueensBuzz.com. 25 January 2012. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- ^ "SELECTED POPULATION PROFILE IN THE UNITED STATES 2017 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates New York-Newark, NY-NJ-CT-PA CSA Chinese alone". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 14 February 2020. Retrieved 27 January 2019.

- ^ a b The Encyclopedia of Global Human Migration. Wiley. 4 February 2013. doi:10.1002/9781444351071.wbeghm122.

- ^ Huang, Chun Chang; Su, Hongxia (1 April 2009). "Climate change and Zhou relocations in early Chinese history". Journal of Historical Geography. 35 (2): 297–310. doi:10.1016/j.jhg.2008.08.006.

- ^ James D. Tracy (1993). The Rise of merchant empires: long-distance trade in the early modern world, 1350-1750. Cambridge University Press. p. 405. ISBN 0-521-45735-1. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- ^ Ho Khai Leong, Khai Leong Ho (2009). Connecting and Distancing: Southeast Asia and China. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 11. ISBN 978-981-230-856-6. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- ^ Derek Heng (2009). Sino-Malay Trade and Diplomacy from the Tenth Through the Fourteenth Century. Ohio University Press. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-89680-271-1. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ Robert S. Wicks (1992). Money, markets, and trade in early Southeast Asia: the development of indigenous monetary systems to AD 1400. SEAP Publications. p. 215. ISBN 0-87727-710-9. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ Malaysia-Singapore-6th-Footprint-Travel, Steve Frankham, ISBN 978-1-906098-11-7

- ^ "Li impressed with Malacca's racial diversity and cendol - Nation - The Star Online". The Star. Malaysia.

- ^ Shih-shan Henry Tsai (1996). The eunuchs in the Ming dynasty. SUNY Press. p. 145. ISBN 0-7914-2687-4. Retrieved 4 February 2011.

- ^ Angela Schottenhammer (2007). The East Asian maritime world 1400-1800: its fabrics of power and dynamics of exchanges. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. xiii. ISBN 978-3-447-05474-4. Retrieved 4 February 2011.

- ^ Gang Deng (1999). Maritime sector, institutions, and sea power of premodern China. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 125. ISBN 0-313-30712-1. Retrieved 4 February 2011.

- ^ Katrien Hendrickx (2007). The Origins of Banana-fibre Cloth in the Ryukyus, Japan. Leuven University Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-90-5867-614-6. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- ^ "Is this young Kenyan Chinese descendant?", China Daily, 11 July 2005, retrieved 30 March 2009

- ^ York, Geoffrey (18 July 2005), "Revisiting the history of the high seas", The Globe and Mail, archived from the original on 26 July 2020, retrieved 30 March 2009

- ^ Frank Viviano (July 2005). "China's Great Armada, Admiral Zheng He". NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC. p. 6. Archived from the original on 17 November 2012. Retrieved 29 September 2011.

- ^ Alex Perry (1 August 2008). "A Chinese Color War". Time. Archived from the original on 6 August 2008. Retrieved 29 September 2011.

- ^ Zhao, Bing (25 December 2015). "Chinese-style ceramics in East Africa from the 9th to 16th century: A case of changing value and symbols in the multi-partner global trade". Afriques. 06 (6). doi:10.4000/afriques.1836.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, inc (2003). The New Encyclopædia Britannica, Volume 8. Encyclopædia Britannica. p. 669. ISBN 0-85229-961-3. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ Barbara Watson Andaya (2006). The flaming womb: repositioning women in early modern Southeast Asia. University of Hawaii Press. p. 146. ISBN 0-8248-2955-7. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

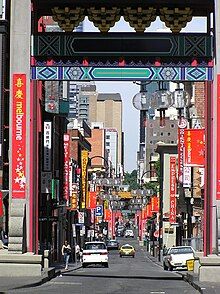

- ^ "Chinatown Melbourne". Retrieved 23 January 2014.

- ^ "Melbourne's multicultural history". City of Melbourne. Retrieved 23 January 2014.

- ^ "World's 8 most colourful Chinatowns". Retrieved 23 January 2014.

- ^ "The essential guide to Chinatown". Melbourne Food and Wine Festival. Food + Drink Victoria. 3 February 2021. Retrieved 11 February 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Han, Enze (2024). The Ripple Effect: China's Complex Presence in Southeast Asia. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-769659-0.

- ^ Wang, Gungwu (1994). "Upgrading the migrant: neither huaqiao nor huaren". Chinese America: History and Perspectives. Chinese Historical Society of America. p. 4. ISBN 0-9614198-9-X.

In its own way, it [Chinese government] has upgraded its migrants from a ragbag of malcontents, adventurers, and desperately poor laborers to the status of respectable and valued nationals whose loyalty was greatly appreciated.

- ^ Peter Kwong and Dusanka Miscevic (2005). Chinese America: the untold story of America's oldest new community. The New Press. ISBN 978-1-56584-962-4.

- ^ Pan, Lynn (1999). The Encyclopedia of the Chinese Overseas. Cambridge, MA, US: Harvard University Press. p. 36. ISBN 0674252101.

- ^ Pan, Lynn (1999). The Encyclopedia of the Chinese Overseas. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. pp. 28–29. ISBN 0674252101.

- ^ Displacements and Diaspora. Rutgers University Press. 2005. ISBN 9780813536101. JSTOR j.ctt5hj582.

- ^ "Chiang Kai Shiek". Sarawakiana. Retrieved 28 August 2012.

- ^ a b Eileen Sullivan (24 November 2023). "Growing Numbers of Chinese Migrants Are Crossing the Southern Border". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 November 2023.

Most who have come to the United States in the past year were middle-class adults who have headed to New York after being released from custody. New York has been a prime destination for migrants from other nations as well, particularly Venezuelans, who rely on the city's resources, including its shelters. But few of the Chinese migrants are staying in the shelters. Instead, they are going where Chinese citizens have gone for generations: Flushing, Queens. Or to some, the Chinese Manhattan..."New York is a self-sufficient Chinese immigrants community," said the Rev. Mike Chan, the executive director of the Chinese Christian Herald Crusade, a faith-based group in the neighborhood.

- ^ "Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: 2011 Supplemental Table 2". U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- ^ "Chinese New Year 2012 in Flushing". QueensBuzz.com. 25 January 2012. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- ^ "SELECTED POPULATION PROFILE IN THE UNITED STATES 2010American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates New York-Newark, NY-NJ-CT-PA CSA Chinese alone". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 14 February 2020. Retrieved 27 January 2019.

- ^ John Marzulli (9 May 2011). "Malaysian man smuggled illegal Chinese immigrants into Brooklyn using Queen Mary 2: authorities". Daily News. New York. Archived from the original on 23 June 2012. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- ^ "Under Xi Jinping, the number of Chinese asylum-seekers has shot up". The Economist. 28 July 2021. Retrieved 25 January 2022.

- ^ Tara John and Yong Xiong (17 May 2024). "Caught between China and the US, asylum seekers live in limbo in New York City". CNN. Retrieved 9 June 2024.

- ^ "Fleeing China's Covid lockdowns for the US - through a Central American jungle". BBC News. 21 December 2022. Retrieved 27 November 2023.

- ^ Yiu, Pak (18 June 2024). "China to see biggest millionaire exodus in 2024 as many head to U.S." Nikkei Asia. Retrieved 22 June 2024.

Sources

[edit]- Amrith, Sunil S. Migration and diaspora in modern Asia (Cambridge University Press, 2011).

- Benton, Gregor, and Hong Liu. Dear China: emigrant letters and remittances, 1820–1980. (U of California Press, 2018).

- Chan, Shelly. "The case for diaspora: A temporal approach to the Chinese experience." Journal of Asian Studies (2015): 107–128. online

- Cooke, Nola; Li, Tana; Anderson, James, eds. (2011). The Tongking Gulf Through History (illustrated ed.). University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0812243369. Retrieved 4 January 2013.

- Ho, Elaine Lynn-Ee. Citizens in Motion: Emigration, Immigration, and Re-migration Across China's Borders (Stanford UP, 2018).

- Lary, Diana (2007). Lary, Diana (ed.). The Chinese State at the Borders (illustrated ed.). UBC Press. ISBN 978-0774813334. Retrieved 4 January 2013.

- McKeown, Adam. "Chinese emigration in global context, 1850–1940." Journal of Global History 5.1 (2010): 95–124.

- Pan, Lynn (1994). Sons of the Yellow Emperor: A History of the Chinese Diaspora. New York, NY: Kodansha America. ISBN 1-56836-032-0.

- Pan, Lynn, ed. (1999). The Encyclopedia of the Chinese Overseas. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674252101.

- Tsai, Shih-Shan Henry (1996). The Eunuchs in the Ming Dynasty (Ming Tai Huan Kuan) (illustrated ed.). SUNY Press. ISBN 0791426874. Retrieved 5 January 2013.

- Wade, Geoff (2005), Southeast Asia in the Ming Shi-lu: an open access resource, Asia Research Institute and the Singapore E-Press, National University of Singapore, retrieved 6 November 2012

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Country Studies. Federal Research Division. [1]

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Country Studies. Federal Research Division. [1]

External links

[edit]- The Rocky Road to Liberty: A Documented History of Chinese American Immigration and Exclusion

- [2]

- Chinese Canadians – A visual history from the UBC Library Digital Collections documenting Chinese settlement in British Columbia