Bhutan–China border

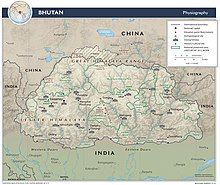

The Bhutan–China border is the international boundary between Bhutan and China, running for 477 km (296 mi) through the Himalayas between the two tripoints with India.[1] The official boundaries remain disputed.[2]

Description

[edit]The border starts in the west at the western tripoint with India just north of Mount Gipmochi. It then proceeds overland to the north-east, across mountains such as Jomolhari (part of this stretch is disputed). The border turns east near Mount Masang Gang, though a large stretch of this section is also in dispute. Near the town of Singye Dzong it turns broadly southeastward, terminating at the eastern tripoint with India. The only land crossing between Bhutan and China is a secret road/trail connecting Tsento Gewog and Phari (27°41′56″N 89°11′21″E / 27.698912°N 89.189139°E) known as Tremo La.

History

[edit]The Kingdom of Bhutan and the People's Republic of China do not maintain official diplomatic relations, and relations are historically tense.[3][4][5]

Bhutan's border with Tibet has never been officially recognised and demarcated. For a brief period in circa 1911, the Republic of China officially maintained a territorial claim on parts of Bhutan.[6] In 1930, Mao Zedong named Bhutan as falling within "the correct boundaries of China" and would later include it in the Five Fingers of Tibet.[7][8] The territorial claim was maintained by the People's Republic of China after the Chinese Communist Party took control of mainland China in the Chinese Civil War in 1949. In 1959, China released a map in A brief history of China where considerable portions of Bhutan as well as other countries was included in its territorial claims.[9]

With the increase in soldiers on the Chinese side of the Sino-Bhutanese border after the 17-point agreement between the local Tibetan government and the central government of the PRC in 1951, Bhutan withdrew its representative from Lhasa.[6][10][11]

The 1959 Tibetan Rebellion and the 14th Dalai Lama's arrival in neighbouring India made the security of Bhutan's border with China a necessity for Bhutan. An estimated 6,000 Tibetans fled to Bhutan and were granted asylum, although Bhutan subsequently closed its border to China, fearing more refugees to come.[6][12] In July 1959, along with the occupation of Tibet, the Chinese People's Liberation Army occupied several Bhutanese exclaves in western Tibet which were under Bhutanese administration for more than 300 years and had been given to Bhutan by Ngawang Namgyal in the 17th century.[9] These included Darchen, Labrang Monastery, Gartok and several smaller monasteries and villages near Mount Kailas.[13][14][15][16]

A Chinese map published in 1961 showed China claiming territories in Bhutan, Nepal and the Kingdom of Sikkim (now a state of India).[6] Incursions by Chinese soldiers and Tibetan herdsmen also provoked tensions in Bhutan. Imposing a cross-border trade embargo and closing the border, Bhutan established extensive military ties with India.[6][10]

During the 1962 Sino-Indian War, Bhutanese authorities permitted Indian troop movements through Bhutanese territory.[6] However, India's defeat in the war raised concerns about India's ability to defend Bhutan. Consequently, while building its ties with India, Bhutan officially established a policy of neutrality.[4][6] According to official statements by the King of Bhutan to the National Assembly, there are four disputed areas between Bhutan and China. Starting from Doklam in the west, the border goes along the mountain ridges from Gamochen to Batangla, Sinchela, and down to the Amo Chhu. The disputed area in Doklam covers 89 square kilometers (km2), while the disputed areas in Sinchulumpa and Gieu cover about 180 km2.[4]

Until the 1970s, India represented Bhutan's concerns in talks with China over the broader Sino-Indian border conflicts.[4] Obtaining membership in the United Nations in 1971, Bhutan began to take a more independent course in its foreign policy.[6] In the U.N., Bhutan, incidentally alongside India, voted in favor of the PRC filling the seat occupied by the ROC and openly supported the "One China" policy.[4][5] In 1974 in a symbolic overture, Bhutan invited the Chinese ambassador to India to attend the coronation of Jigme Singye Wangchuk as the king of Bhutan.[4] In the 1980s, Bhutan relinquished its claim to a 154 square miles (400 km2) area called Kula Khari on its northern border with China.[17] In 1983, the Chinese Foreign Minister Wu Xueqian and Bhutanese Foreign Minister Dawa Tsering held talks on establishing bilateral relations in New York. In 1984, China and Bhutan began annual, direct talks over the border dispute.[4][10]

In 1996, China offered to trade Jakarlung and Pasamlung in exchange for a smaller tract of disputed area around Doklam, Sinchulumpa, and Gieu. This was accepted by Bhutan in principle.[18] In 1998, China and Bhutan signed a bilateral agreement for maintaining peace on the border.[19] In the agreement, China affirmed its respect for Bhutan's sovereignty and territorial integrity and both sides sought to build ties based on the Five Principles of Peaceful Co-existence.[4][5][10] However, China's building of roads on what Bhutan asserts to be Bhutanese territory, allegedly in violation of the 1998 agreement, has provoked tensions.[10][11] In 2002, China presented what it claimed to be evidence, asserting its ownership of disputed tracts of land; after negotiations, an interim agreement was reached.[4]

On 11 August 2016 Bhutan Foreign Minister Damcho Dorji visited Beijing, capital of China, for the 24th round of boundary talks with Chinese Vice President Li Yuanchao. Both sides made comments to show their readiness to strengthen co-operations in various fields and hope of settling the boundary issues.[20] In 2024, The New York Times reported that, according to satellite imagery, China had constructed villages inside of disputed territory within Bhutan.[21] Chinese individuals, called "border guardians," received annual subsidies to relocate to newly built villages and paid to conduct border patrols.[21] At least 22 Chinese villages and settlements have been constructed inside of disputed territory.[22]

Doklam crisis, 2017

[edit]On June 29, 2017, Bhutan protested to China against the construction of a road in the disputed territory of Doklam, at the meeting point of Bhutan, India and China.[23] On the same day, the Bhutanese border was put on high alert and border security was tightened as a result of the growing tensions.[24] A stand-off between China and India has endured since mid June 2017 at the tri-junction adjacent to the Indian state of Sikkim after the Indian army blocked the Chinese construction of a road in what Bhutan and India consider Bhutanese territory. Both India and China deployed 3000 troops on June 30, 2017.[25] On the same day, China released a map claiming that Doklam belonged to China. China claimed, via the map, that territory south to Gipmochi belonged to China and claimed that it was supported by the Convention of Calcutta.[26] On July 3, 2017, China told India that former Indian prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru accepted the Convention of Calcutta.[27] China claimed on July 5, 2017, it had a "basic consensus" with Bhutan and there was no dispute between the two countries.[28] On August 10, 2017, Bhutan rejected Beijing's claim that Doklam belongs to China.[29]

Sakteng Wildlife Sanctuary

[edit]On 2 June 2020, China raised a new dispute over territory that has never come up in boundary talks earlier. In the virtual meeting of the Global Environment Facility (GEF), China objected to a grant for the Sakteng Wildlife Sanctuary in eastern Bhutan's Trashigang District claiming that the area was disputed.[30][31][32]

Three Step Roadmap MoU

[edit]On October 14, 2021, Bhutan and China signed a MoU for a three step roadmap to expedite boundary negotiation talks.[33] Boundary negotiations between Bhutan and China had been initiated in 1984, but had seen little progress in the previous 5 years, initially due to the Doklam crisis and later due to the coronavirus pandemic. The talks would not cover the trijunction area between India, Bhutan and China. As per a 2012 understanding between India and China, the trijunction areas would only be resolved by consultation with all three involved parties.[34]

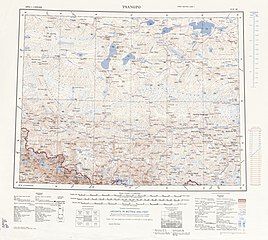

Historical maps

[edit]Historical maps of the border area from west to east in the International Map of the World and Operational Navigation Chart, mid-late 20th century:

References

[edit]- ^ "Bhutan". CIA World Factbook. Archived from the original on June 12, 2007. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- ^ McCarthy, Simone; Gan, Nectar (2024-11-05). "China is building new villages on its remote Himalayan border. Some appear to have crossed the line". CNN. Retrieved 2024-11-05.

- ^ Sirohi, Seema (14 May 2008). "A New Bhutan Calling". Outlook. Archived from the original on 25 November 2020. Retrieved 30 May 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Bhutan-China relations (5 July 2004). BhutanNewsOnline.com. Accessed 30 May 2008.

- ^ a b c India and the upcoming Druk democracy Archived 13 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine (May 2007). HimalMag.com. Accessed 30 May 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Bhutan - China relations Archived 2017-08-03 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 30 May 2008.

- ^ "Bhutan's Relations With China and India". The Jamestown Foundation. Archived from the original on 2021-01-08. Retrieved 2023-10-10.

- ^ Siddiqui, Maha (18 June 2020). "Ladakh is the First Finger, China is Coming After All Five: Tibet Chief's Warning to India". News18. Archived from the original on 24 June 2020. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- ^ a b "Economic and political relations between Bhutan and the neighbouring countries pp-168" (PDF). Institute of developing economies Japan external trade organisation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 December 2020. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- ^ a b c d e In Bhutan, China and India collide (12 January 2008). AsiaTimes.com. Accessed 30 May 2008.

- ^ a b Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies Archived 29 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine (8 April 2008). IPCS.org. Accessed 30 May 2008.

- ^ Bhutan: a land frozen in time Archived 2010-11-11 at the Wayback Machine (9 February 1998). BBC. Accessed 30 May 2008.

- ^ Ranade, Jayadeva (16 July 2017). "A Treacherous Faultline". The Pioneer. Archived from the original on 27 June 2020. Retrieved 10 October 2023.

- ^ K. Warikoo (2019). Himalayan Frontiers of India: Historical, Geo-Political and Strategic Perspectives. Routledge. p. 240. ISBN 9781134032945.

- ^ Arpi, Claude (16 July 2016). "Little Bhutan in Tibet". The Statesman. Archived from the original on 26 June 2020. Retrieved 10 October 2023.

- ^ "Ladakhi and Bhutanese Enclaves in Tibet" (PDF). John Bray. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-12-02. Retrieved 2023-10-10.

- ^ Barnett, Robert (May 7, 2021). "China Is Building Entire Villages in Another Country's Territory". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on May 7, 2021. Retrieved May 21, 2024.

- ^ "Bhutan-China Relation". Bhutan News Online. 2002-10-24. Archived from the original on 2002-10-24.

- ^ Singh, Swaran (2016). "China Engages Its Southwest Frontier". The new great game : China and South and Central Asia in the era of reform. Thomas Fingar. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. p. 163. ISBN 978-0-8047-9764-1. OCLC 939553543.

- ^ "China hopes to forge diplomatic ties with Bhutan". Xinhua News. Archived from the original on August 11, 2016. Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- ^ a b Xiao, Muyi; Chang, Agnes (2024-08-10). "China's Great Wall of Villages". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2024-08-10.

- ^ "Forceful Diplomacy: China's Cross-Border Villages in Bhutan". Turquoise Roof. 2024-10-15. Retrieved 2024-10-18.

- ^ "Bhutan protests against China's road construction". The Straits Times. Jun 30, 2017. Archived from the original on 2017-07-29. Retrieved 2017-06-30.

- ^ "Bhutan issues scathing statement against China, claims Beijing violated border agreements of 1988, 1998". Firstpost. Jun 30, 2017. Archived from the original on 2017-07-02. Retrieved 2017-06-30.

- ^ "Border face-off: China and India each deploy 3,000 troops - Times of India". The Times of India. 30 June 2017. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- ^ "EXCLUSIVE: China releases new map showing territorial claims at stand-off site". July 2017. Archived from the original on 4 July 2017. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- ^ "Nehru Accepted 1890 Treaty; India Using Bhutan to Cover up Entry: China". 3 July 2017. Archived from the original on 30 July 2017. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- ^ PTI (5 July 2017). "No dispute with Bhutan in Doklam: China". Archived from the original on 29 July 2017. Retrieved 6 July 2017 – via The Economic Times.

- ^ PTI (10 August 2017). "Bhutan rejects China's claim in Doklam: China". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 10 August 2017. Retrieved 10 August 2017.

- ^ "Bhutan counters China's claim over its territory". Phayul. 2 June 2020. Archived from the original on 25 November 2020. Retrieved 10 October 2023.

- ^ "Why Did China Claim A Part Of Bhutan's Territory Now?". Huffingon Post. 3 July 2020. Archived from the original on 20 November 2020. Retrieved 10 October 2023.

- ^ "China throws up another 'disputed' territory claim against Bhutan, seen as targeting India". Tibetan Review. 2 July 2020. Archived from the original on 1 October 2020. Retrieved 10 October 2023.

- ^ Haidar, Suhasini (14 October 2021). "Bhutan, China sign MoU for 3-step roadmap to expedite boundary talks". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 11 August 2022. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- ^ Chaudhury, Dipanjan Roy (16 October 2021). "Bhutan-China border talks deal not to involve Trijunction with India". The Economic Times. Archived from the original on 12 August 2022. Retrieved 12 August 2022.